Abstract

Background

Spinal pain in young people is a significant source of morbidity in industrialised countries. The carriage of posterior loads by young people has been linked with spinal pain, and the amount of postural change produced by load carriage has been used as a measure of the potential to cause tissue damage. The purpose of this review was to identify, appraise and collate the research evidence regarding load-carriage related postural changes in young people.

Methods

A systematic literature review sought published literature on the postural effects of load carriage in young people. Sixteen databases were searched, which covered the domains of allied health, childcare, engineering, health, health-research, health-science, medicine and medical sciences. Two independent reviewers graded the papers according to Lloyd-Smith's hierarchy of evidence scale. Papers graded between 1a (meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials) and 2b (well-designed quasi-experimental study) were eligible for inclusion in this review. These papers were quality appraised using a modified Crombie tool. The results informed the collation of research evidence from the papers sourced.

Results

Seven papers were identified for inclusion in this review. Methodological differences limited our ability to collate evidence.

Conclusions

Evidence based recommendations for load carriage in young people could not be made based on the results of this systematic review, therefore constraining the use of published literature to inform good load carriage practice for young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spinal pain affecting the cervical, thoracic or lumbar regions, is one of the most costly and disabling problems affecting individuals in industrialized countries [1–3]. Population-based surveys of spinal pain variably report a point prevalence of 15%-30%, a one-year prevalence of 50%, and a lifetime prevalence of 60%-80% [4–6]. Furthermore, this type of pain places a significant economic burden on the individual and the community. In Australia, spinal pain is the leading musculoskeletal cause of health system expenditure, with an estimated total cost of $700 million in 1993–1994 [7].

The spine has been identified as a common site of pain in young people as well as adults [8–14]. Estimates of the point prevalence of spinal pain in 12–18 year-old school students varies between 15 and 44% (age and gender dependant) [8–14]. It has been hypothesised that spinal pain experienced in childhood and adolescence is a significant risk for spinal pain experienced in later life [15, 16], although there are few longitudinal studies to verify this. Nevertheless, the investigation and reduction of contributing factors to spinal pain in young people may be an appropriate step towards reducing the burden of spinal pain on our society.

Load carriage has been associated with spinal pain in both adolescents and adults [17, 18], although it is not ethically possible to experimentally investigate the causal nature of this relationship. A change in spinal posture has been accepted by experts as a plausible intermediary measure of the potential for spinal pain due to load carriage [19–21]. To our knowledge, measurement of load carriage induced postural change is the only method of experimentally approximating the potential for load carriage to induce spinal pain that is currently used by researchers.

The use of postural change as a proximate measure involves the hypothesis that larger postural displacement from the unloaded position increase the likelihood of developing spinal pain. By experimentally manipulating loads and how they are carried, and measuring the degree of induced postural change, researchers' estimate the potential of posterior load carriage to induce spinal pain. The effect of load weight [19, 20],[22–25], method of load carriage (2 strapped backpack, 1 strapped backpack) [21, 22], position of the load on the spine [23], time of load carriage [20, 22], and distance of load carriage [19] on young people have been investigated in this manner. An understanding of load-carriage-induced postural displacements, and their potential to produce spinal pain, is needed to direct recommendations for load carriage by young people with the aim of minimising their spinal pain.

This article reports on a systematic review undertaken to identify, appraise and collate the research evidence regarding load-carriage related postural changes in young people.

Methods

Literature search

We employed a comprehensive search strategy to source papers that described the postural effects of load carriage on the spinal health of young people under the age of 18 years. Allied health, child care, health, health-research, health-science, medicine and medical sciences databases were accessed, including Academic Search Elite, AEI, AMED, AMI, APAIS, Ausport Med, AUSThealth, Australian Public Affairs, Blackwell Science and Munksgaard Online Journals, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, ERIC, FAMILY, MEDLINE, Science Direct and Wiley InterScience. Our search strategy consisted of three stages:

1. Combinations of specific keyword searches were used in each database; ('backpack' OR 'bag' OR 'load' OR 'rucksack') AND ('youth' OR 'child/ren' OR 'adolescen/t/nce') AND ('back' OR 'posture' OR 'pain'). The appropriate truncation symbol for each database was used with each key word. The internet and library databases were also searched using these terms.

2. Time and language restraints were set;

> Years of publication from January 1985 to November 2002.

> English language only.

3. Papers were excluded if the main outcome measured was not postural change.

Hierarchy of evidence

Two experienced research physiotherapists independently assessed all papers sourced. First, the level of evidence of each paper was determined according to the hierarchical system of Lloyd-Smith [26] (Table 1). The level reflects the degree to which bias has been considered within study design, with a lower rating on the hierarchy indicating less bias. Only papers that scored between 1a and 2b on Lloyd-Smith's scale [26] were included in this review. In this way we could ensure that recommendations for load carriage advocated by this review were based on findings of high-level evidence.

Quality appraisal

Second, we assessed the quality of these papers based on a modified version of a well-established quality appraisal tool recommended by Crombie [27]. An extra appraisal item, 'Sensitivity of outcome tool' was added to the published tool since the use of an insensitive outcome tool may have meant that differences in posture between conditions were not measured, significantly impacting on study outcomes [28]. The quality of each paper was scored according to factors shown in Figure 1. Prior to scoring, it was necessary to clarify one of the appraisal items to ensure that reviewers were consistent in their approach. Reviewers recognized that study design is unlikely to account for all potential biases, therefore appraisal item number 11 (Figure 1) 'Attention to potential biases' was scored positively if the paper acknowledged the potential impact of all likely biases. One point was allocated for fulfillment of each quality appraisal item. The maximum score, (indicating high quality), was 16, with the lowest possible score being zero. The methodological quality of each study was subsequently rated as low (0–5 points), moderate (6–11 points), or high (12–16 points), similar to the procedure outlined by Geytenbeek [29]. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by consensus building. We reported on critical appraisal items which were poorly addressed in the papers.

Modified Crombie [27] quality appraisal tool used to score the quality of papers

Conditions (static/ dynamic)

Third, we recorded the condition of bag carriage that was being assessed (static or dynamic). We hypothesized that the testing condition would impact on the study outcomes since walking requires different muscular activity compared to static standing [30].

Measurement methods

Fourth, we recorded the method of measurement of posture described in each of the papers sourced. This information helped identify whether the results of the studies could be synthesised.

Study outcomes

Information from our four stages of assessment was utilised to guide the collation of research evidence regarding load-carriage related postural changes in young people, for variables such as load weight, method of load carriage (2 strapped backpack, 1 strapped backpack), position of load on the spine, time of load carriage, and distance of load carriage.

Results

Literature search

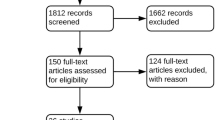

Four hundred and eighty eight papers were identified from our initial search of the databases. Three hundred and twelve of these papers were excluded from our review, as they did not specifically measure postural effects of load carriage in young people. One appropriate paper was found through the internet and library database searches.

Hierarchy of evidence and quality appraisal

The remaining 177 papers were assessed for level of evidence. Only seven of these papers scored 1a to 2b [19–25] in the hierarchy of evidence [26]. None of the papers were meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (level 1a), three of the papers were randomised controlled studies (level 1b) [19, 23, 24], and four were well-designed, non-randomised studies (level 2a) [20–22, 25].

Table 2 provides the total number of papers (maximum of seven) that fulfilled the criteria for each appraisal item. Table 3 provides the following information relating to the publications included in this systematic review; hierarchy level, score achieved for the quality appraisal items most poorly addressed by the studies (items for which four or less studies scored a point), appraisal score and quality category. Based on the results of the quality appraisal process, one of the seven papers was ranked as high quality [23], with the remainder being of moderate quality [19–22],[24, 25].

Conditions (static/ dynamic), measurement methods, study outcomes

Table 4 (additional file 1) summarises the conditions (static/ dynamic), measurement methodology and outcomes of the seven papers. One paper measured the effects of static load carriage [23], four measured the effects of dynamic load carriage [19, 20],[24, 25], and two papers studied effects of both conditions [21, 22]. There were similarities in methods of measurement of posture across the seven papers, although no two papers used identical approaches. Inconsistent results were found across the seven studies of the effects of load related variables that were investigated. Differences in study methodology and quality, condition under which posture was assessed (static/ dynamic), and postural measurement should be considered as reasons for lack of consistency of outcomes (see Table 4). Table 4 highlights the differences in methodology and outcomes of the eligible studies, and underlies the difficulties of undertaking any comparisons or syntheses of results.

Discussion

Evidence-based practice focuses on finding consistencies across studies that have investigated the same interventions on the same study populations [31]. The collation of information from similar studies should lead to evidence-based recommendations. Load carriage by young people is a contentious issue [32, 33], because of concerns for morbidity related to spinal pain. Although much has been written on the topic of load induced postural change and young people (as evidenced by the number of papers sourced for this review), very little of the available literature was of high quality. Only seven papers sourced met our requirements for level of evidence, and all contained methodological limitations, despite being graded as having moderate and high methodological quality. These limitations, such as a lack of randomisation of order of testing conditions, and insensitive, unreliable and invalidated outcome tools, limited our ability to draw definitive conclusions from their outcomes. In addition, differences in study design and inconsistencies in study outcomes constrained the production of evidence-based load carriage recommendations for young people.

Assessment of the quality of studies is a vital part of the systematic review process as it guides the interpretation of the results or outcome of each paper [34]. Many quality scales and checklists have been published [35]. However these tools should be used with caution, as they are generally based on 'accepted' criteria, and often have not undergone validation, nor reflect key issues pertinent to the area under review. Therefore, it is possible for a paper to be scored moderately by a quality tool, yet still contain significant methodological limitations, as occurred in this systematic review. The quality appraisal items which received a score in four or less of the seven studies were (as seen in Table 3);

• Appropriateness of design to meet the aims The lack of randomization of the order of testing conditions in three papers reviewed is likely to have produced a systematic postural change, affecting the outcome of these studies [28, 36].

• Adequate specifications of the subject group Musculoskeletal injury, or disease processes which affect musculoskeletal integrity, could affect postural response to load carriage [36]. Therefore the lack of specific exclusion criteria in six reviewed papers may have decreased the validity of findings.

• Justification of sample size Unjustified sample sizes suggests that six of the seven studies may lack sufficient power to detect significant results [36]. Therefore, it is unlikely that results of these papers can be generalized to the wider population, even within the gender/ age group of study subjects.

• Likelihood of reliable and valid measures/ sensitivity of outcome tool It was not known, in the majority of the papers reviewed, whether the outcome measure assessed the construct it was supposed to measure (validity), assessed the construct in a consistent manner on repeated occasions of assessment (reliability) or could detect meaningful changes in the construct over time (sensitivity). These three factors are critical in determining whether study outcomes are meaningful [28].

• Attention to potential biases None of the seven papers acknowledged all potential biases to study outcomes. This information is critical in determining the relevance of study findings [36].

• Implications in real life As assessed throughout the quality appraisal stage, most papers (6/7) did not produce results which could be readily generalized to 'real life' due to small and/ or unjustified sample size, non-randomised subject selection process, and subject group limited to one gender or to a specific age [36].

The appropriateness of the use of load induced postural change as a proximate measure of spinal pain has not been widely discussed in published literature and needs to be given further attention by researchers in the future.

Conclusion

From a public health perspective, concerted efforts should be directed to decreasing spinal pain experienced by young people to lessen the future burden of adult spinal pain on modern societies. The first step in this process is to conduct rigorous research to determine the postural effects of load carriage in young people. This review outlines the areas which require more attention, these being: the inclusion of randomisation of order of conditions tested; adequate specifications of subject group (including appropriate exclusion criteria); justified sample sizes; reliable, valid and sensitive outcome tools; attention to potential biases, and the ability of study outcomes to be generalised to 'real life'.

This review has highlighted that there is currently no standardised approach to the study of load-induced postural change for young people. For example, static and dynamic postural conditions are being assessed, and within these postural domains the methodology used to measure changes in posture varies significantly. As a consequence, difficulty exists in comparing results, precluding meta-analysis [30]. This lack of consensus regarding standardised data collection may be the result of research being undertaken by different groups, over many continents. Therefore, it is important that researchers reach international consensus regarding the most appropriate method(s) used to assess postural change in order to hasten the development of evidence-based recommendations for the carriage of loads by young people.

Author's contributions

ES undertook the literature search, and reviewed the level of evidence, methodological quality, conditions tested, and measurement methods of each of the sourced papers. ES coordinated the analysis of results of this review.

AB was the second reviewer for the level of evidence, methodological quality, conditions tested, and measurement methods stages of this review. AB played a significant role in the analysis of results of the review also.

KG conceived this systematic review, participated in its' design and coordination, and contributed to the analysis of results of the review.

All authors participated in the writing of this review, and read and approved of the final manuscript.

References

Lanes T, Gauron E, Spratt K, Wernimont T, Found E, Weinstein J: Long-term follow-up of patients with low back pain treated in a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. Spine. 1995, 20: 801-806.

Tulder M, Koes B, Bouter L: A cost- of – illness study of back pain in The Netherlands. Pain. 1995, 62: 233-240.

Tulder M, Koes B, Bouter L: Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 1997, 22: 2128-2156.

Frymoyer J: Back pain and sciatica. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988, 318: 291-300.

Kelsey JL, Mundt DJ, Golden AL: Epidemiology of low back pain. In The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain. Edited by: Jayson M. 1992, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 357-546.

Nachemson A, Waddell G, Norlund A: Epidemiology of neck and back pain. In Neck and back pain: The scientific evidence of causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Edited by: Nachemson A, Jonsson E. 2000, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 165-188.

Mathers C, Penn R: Health system costs of injury, poisoning and musculo-skeletal disorders in Australia 1993–94. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, AIHW Catalogue No. HWE 12 (Health and Welfare Expenditure Series No. 6). 1999

Balague F, Dutoit G, Waldburger M: Low back pain in schoolchildren. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1988, 20: 175-179.

Ebrall P: Some anthropometric dimensions of male adolescents with idiopathic low back pain. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 1994, 17: 296-301.

Erkintalo M, Salminen J, Alanen A, Paajanen H, Kormano M: Development of degenerative changes in the lumbar vertebral disk: results of a prospective MR imaging study in adolescents with and without low-back pain. Radiology. 1995, 196: 529-533.

Nissinen M, Heliovaara M, Seitsamo MS, Alaranta H, Poussa M: Anthropometric measurement and the incidence of low back pain in a cohort of pubertal children. Spine. 1994, 19: 1367-1370.

Olsen TL, Anderson RL, Dearwater SR, Krista AM, Cauley JA, Aaron DJ, LaPorte RE: The epidemiology of low back pain in an adolescent population. American Journal of Public Health. 1992, 82: 606-608.

Salminen JJ, Erkintalo M, Laine M, Pentti J: Low back pain in the young: A prospective three-year follow up study of subjects with and without low back pain. Spine. 1995, 20: 2101-2108.

Troussier B, Davoine P, de Gaudemaris R, Fauconnier J, Phelip X: Back pain in school children; A study among 1178 pupils. Scandinavian Journal Of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1994, 26: 143-146.

Adams MA, Mannion AF, Dolan P: Personal risk factors for first time low back pain. Spine. 1999, 24 (23): 2497-2505.

Salminen JJ, Erkintalo MO, Pentti J, Oksanen A, Kormano MJ: Recurrent low back pain and early disc degeneration in the young. Spine. 1999, 24 (13): 1316-1321.

Grimmer K, Williams M: Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000, 31: 343-360.

Johnson RF, Knapik JJ: Symptoms during load carrying: effects of mass and load distributions during a 20-km road march. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1995, 81: 331-338.

Hong Y, Cheung CK: Gait and posture responses to backpack load during level walking in children. Gait and Posture. 2003, 17 (1): 28-33.

Kennedy L, Lawlor F, O'Connor A, Dockrell S, Gormley J: An investigation of the effects of schoolbag carriage on trunk angle. Physiotherapy Ireland. 1999, 20 (1): 2-8.

Pascoe DD, Pascoe DE, Wang YT, Shim DM, Kim CK: Influence of carrying book bags on gait cycle and posture of youths. Ergonomics. 1997, 40 (6): 631-641.

Chansirinukor W, Wilson D, Grimmer K, Dansie B: Effects of backpacks on students: measurement of cervical and shoulder posture. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2001, 47 (2): 110-116.

Grimmer K, Dansie B, Milanese S, Pirunson P, Trott P: Adolescent standing postural response to backpack loads: a randomised controlled experimental study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2002, 3 (10): http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/3/10

Hong Y, Brueggemann G: Changes in gait patterns in 10-year-old boys with increasing loads when walking on a treadmill. Gait and posture. 2000, 11: 254-259.

Wong ASK, Hong Y: Ergonomic analysis on carrying of school bags by primary school students. Hong Kong Journal of Sports Medicine and Sports Science. 1997, 4: 42-48.

Lloyd-Smith W: Evidence-based practice and occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997, 60 (11): 474-478.

Crombie IK: The pocket guide to critical appraisal. 1996, London: BMJ Publishing Group

Streiner DL, Norman GR: Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 1995, New York: Oxford University Press

Geytenbeek J: Evidence for effective hydrotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2002, 88 (9): 514-529.

Whittle M: Gait analysis: an introduction. 2002, Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Gray JA, Hayes BR, Richardson SW: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. British Medical Journal. 1996, 312: 71-72.

Negrini S, Carabalona R, Sibilla P: Backpacks as a daily load for schoolchildren. Lancet. 1999, 354 (9194): 1974-1978.

Negrini S, Carabalona R: Backpacks on! Schoolchildren's perceptions of load, associations with back pain and factors determining the load. Spine. 2002, 27 (2): 187-195.

Mulrow CD: Rationale for systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 1994, 309 (6954): 597-599.

Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell T, Walsh S: Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials; an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1995, 16 (1): 62-73.

Elwood M: Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials. 1998, New York: Oxford University Press

Lucas G: General Orthopaedics. In Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care. Edited by: Greene W. 2001, USA: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 2

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/4/12/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Once the seven papers to be included in this review had been identified, we acknowledged that there was a potential for bias in our reviewing process. This potential arose from the fact that our third author, Dr Grimmer, is also an author of two of the seven reviewed papers (Chansirinukor et al 2001, Grimmer et al 2002). Therefore, she was not involved in the hierarchy of evidence or quality appraisal stages of this systematic review. It is important to note that the two reviewers involved in these stages (the first and second authors of this paper) were not involved in Dr Grimmer's two papers, or the research described within, which were included in the systematic review.

Electronic supplementary material

12891_2003_48_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional File 1: Descriptive data. Results of conditions tested, measurement methods and study outcomes stages of the systematic review (DOC 34 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Steele, E., Bialocerkowski, A. & Grimmer, K. The postural effects of load carriage on young people – a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 4, 12 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-4-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-4-12