Abstract

Background

We sought to determine whether socio-economic status (SES) is an independent predictor of outcome following total knee (TKR) and hip (THR) replacement in Australians.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, we included patients undergoing TKR and THR in a public hospital in whom baseline and 12-month follow-up data were available. SES was determined using the Australian Bureau of Statistics ‘Index of Relative Advantage and Disadvantage’. Other independent variables included patients’ demographics, comorbidities and procedure-related variables. Outcome measures were the International Knee Society Score and Harris Hip Score pain and function subscales, and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) physical and mental component scores.

Results

Among 1,016 patients undergoing TKR and 835 patients undergoing THR, in multiple regression analysis, SES score was not independently associated with pain and functional outcomes. Female sex, older age, being a non-English speaker, higher body mass index and presence of comorbidities were associated with greater post-operative pain and poorer functional outcomes following arthroplasty. Better baseline function, physical and mental health, and lower baseline level of pain were associated with better outcomes at 12 months. In univariate analysis, for TKR, the improvement in SF-12 mental health score post arthroplasty was greater in patients of lower SES (3.8 ± 12.9 versus 1.5 ± 12.2, p = 0.008), with a statistically significant inverse association between SES score and post-operative SF-12 mental health score in linear regression analysis (coefficient−0.28, 95% CI: −0.52 to −0.04, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

When adjustments are made for other covariates, SES is not an independent predictor of pain and functional outcome following large joint arthroplasty in Australian patients. However, relative to baseline, patients in lower socioeconomic groups are likely to have greater mental health benefits with TKR than more privileged patients. Large joint arthroplasty should be made accessible to patients of all SES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Joint replacement surgery is one of the most common and costly surgical procedures performed in developed countries [1–3]. Despite technical advances in orthopaedic surgery, there remain many patient-related factors that influence the outcome of large joint arthroplasty [4–8]. Previous studies have indicated that lower socioeconomic status (SES) may be associated with worse outcomes post total knee (TKR) and hip (THR) replacement [9–14]. Possible reasons for this include low motivation, poor health literacy, nutrition, housing and living conditions among those in lower socio-economic groups. The impact of SES on the outcomes of arthroplasty has important implications in relation to selection of suitable patients for joint replacement, and strategies such as psychosocial interventions to optimize the outcomes of this procedure.

Due to differences in socio-economic fabric, ethnic composition, health care systems and cultural expectations, the relative importance of SES as a predictor of outcome post TKR and THR may differ among nations. The Australian ‘public’ health care system provides government subsidized health care for all Australians. Hospital-based services, including elective surgical procedures such as arthroplasty, are free of charge to patients. Accordingly, Australians of all socioeconomic backgrounds access these services. In this study, we sought to determine the association between SES and outcomes in Australian patients undergoing TKR or THR in a specialized ‘public hospital’ care setting.

Methods

Setting and patients

This study was conducted at St. Vincent’s Hospital, a 460-bed university-affiliated tertiary referral centre situated in the central metropolitan region of Melbourne, Australia. All patients who underwent primary TKR or THR (arthroplasty), between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2009, in whom baseline and 12-month follow-up data were available, were eligible for enrolment into the study. For patients who underwent staged bilateral joint replacement, only the second procedure was included in the analyses. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne.

Data collection

Patients attended a multidisciplinary pre-admission clinic within eight weeks prior to surgery, wherein ‘baseline’ pre-operative data were collected according to a standardized protocol. Data included demographics, diagnosis and co-morbidities. Patients were then followed through their procedure and details such as prosthesis type and peri-operative interventions were recorded. Health related questionnaires were administered to patients pre- and 12 months post-surgery. These patient-reported measures were the International Knee Society Score (IKSS) [15], the Harris Hip Score (HHS) [16] and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [17]. Follow-up captured outcomes including death, re-hospitalization and complications.

Main independent variable

The main independent (‘predictor’) variable in this study was socio-economic status (SES). In order to determine SES, the residential postcode of each patient was matched to the corresponding Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) ‘Index of Relative Advantage and Disadvantage’ , which incorporates variables such as income, education, occupation, housing and employment [18]. This index was developed using data from the entire Australian population surveyed in the most recent nation-wide ‘census’. This index summarizes the socio-economic characteristics of subjects within an area [18], and is reported as a ranked score from one to ten (ten equal deciles), with one representing the most disadvantaged and ten the most advantaged areas.

Covariates

Patient characteristics

All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), aetiology of knee or hip joint disease, non-English speaking background, history of contralateral joint replacement and presence of comorbidities. Comorbidities were measured using the Charlson co-morbidity Index (CCI) [19]. The CCI is a widely used and validated measure consisting of a weighted scale of 17 co-morbidities expressed as a summative score [19]. The CCI was calculated using co-morbidity data recorded during the pre-operative medical assessment and the anaesthetic assessment on the day of surgery. The CCI was subsequently adjusted for age [20].

Procedure-related variables

For TKRs, analyses were adjusted for prosthesis type (cruciate retaining, posterior stabilizing or ultra-congruent) and patellar resurfacing. For THRs, analyses were adjusted for cemented versus non-cemented prosthesis. Post-operative complications were also recorded.

Outcome variables

For TKR’s, the outcome variables were IKSS pain (IKSSPain) and function (IKSSFunction) subscales, and SF-12 recorded at 12 months post arthroplasty. The IKSS is a validated scoring system for TKR [21], and good inter-observer reproducibility for the pain and function subscales has been demonstrated [22]. IKSSPain is assessed on a subscale that ranges from no pain (50 points) to mild/occasional (45 points), mild on stairs (40 points), mild on walking and stairs (30 points), moderate occasional (20 points), moderate continuous (10 points) and severe (0 points) pain. The IKSSFunction is based on walking distance, ability to climb stairs and the use of gait aids; the score ranges from 0–100, with a lower score indicating greater functional limitation.

The SF-12 is a multipurpose, generic measure of health status that measures eight health concepts from which two distinct component scores are derived; the physical component score (PCS) and the mental component score (MCS) [17]. Both component scores are designed to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with lower scores indicating greater physical or mental health impairment [23]. A score of ≥ 50 indicates no impairment; 40–49 mild impairment; 30–39 moderate impairment; and < 30 severe impairment. The SF-12 is commonly used to measure physical and mental wellbeing in the clinical setting [24] and specifically in both TKR and THR [25, 26]; it is validated for use in the Australian population [27].

For THRs, the outcome variables were HHS pain (HHSPain), and function (HHSFunction) subscales and SF-12 at 12 months post arthroplasty. HHSPain and HHSFunction are two of the four subscales of the HHS [16]. HHSPain score ranges from no pain (44 points) to slight (40 points), mild (30 points), moderate (20 points), severe (10 points) pain, and disabled (0 points). The functional score range is from 0–47 and assessment is based on walking distance, ability to climb stair, the use of gait aids, limping, ability to don shoes and socks, catch public transport and sit. A lower score indicates greater functional limitation.

All patients were mailed health questionnaires to complete and return at their pre-surgery or follow-up assessments. Patients who did not return during their assessment were contacted by telephone by a person independent of the research team.

Statistical analysis

For each of TKR’s and THR’s, patient characteristics and procedure-related variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) for continuous variables, and proportions (percentages) for categorical variables. For each of the TKR and THR datasets, patients were divided into those with ‘low’ SES score ≤ 5 (SESLow) and ‘high’ SES score ≥ 6 (SESHigh), and univariate methods (t-test, chi-square and analysis of variance) were used to compare characteristics in the two groups.

Linear regression models were run to determine the independent predictors (including SES score on a continuous scale from 1 to 10) of each of the outcome variables: IKSSPain, IKSSFunction, PCSKnee and MCSKnee, HHSPain, HHSFunction, PCSHip and MCSHip. For each outcome, the dependent variable was the outcome measure at 12 months post-surgery, with the pre-operative ‘baseline’ measures included as independent variables. Linearity was tested using plots of observed versus predicted values and plots of residuals versus predicted values in order to ensure that the linearity assumption was satisfied for regression modelling. We also ran models wherein the dependent variable was the change in outcome measure (post-operative minus pre-operative); the results were very similar to the first set of models and therefore we have not presented these here (see Additional file 1).

Results of linear regression were presented as a coefficient (parameter estimate) for each independent variable, with corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and p value. P values ≤ 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA 11 software (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA).

Results

A total of 1,212 TKR’s in 1,065 patients and 982 THR’s in 891 patients were performed during the study period. For patients who underwent staged bilateral joint replacement the second procedure was included in the analysis. A total of 105 patients were excluded due to; deceased prior to 12 months follow-up (12 knees, 12 hips), underwent simultaneous procedure (1 knee), revision of prosthesis prior to 12 months follow-up (3 knees, 9 hips), underwent contralateral or other large joint arthroplasty within 12 months (15 knees, 20 hips), did not complete surveys at both time-points (18 knees, 15 hips). Therefore follow-up data was available for 1016/1065 (95.4%) of patients who underwent TKR and 835/891 (93.7%) of patients who underwent THJR.

Knee arthroplasty analyses

Characteristics of the 1,016 patients who underwent TKR are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The distribution of SES scores among patients is presented in Figure 1. The mean ± SD SES score was 6.3 ± 2.6, with a median of 7.

The Mean ± SD CCI at surgery was 1.8 ± 2.2. The mean ± SD number of comorbidities per patient was 2.7 ± 1.5. Complications occurred in 222 (21.9%) and included medical (n = 106), wound (n = 57) and orthopaedic (n = 40) complications; 19 patients had a minor complication that did not require significant intervention or substantially prolong length of stay. An unplanned readmission was required in 88 (8.7%) patients and an additional unplanned procedure was required in 56 (5.5%) patients; the most common indications for this were wound complications.

Association of SES and knee arthroplasty

SES scores were initially categorized into ‘low’ (SESLow; SES score 5 or less) and ‘high’ (SESHigh; SES score 6 or higher) for descriptive purposes and for univariate analysis. In univariate analysis (Table 3), a significantly higher proportion of patients in the SESLow category were obese (69.0% vs 60.2%, p = 0.02) than in the SESHigh category. Whilst patients in the SESLow category had a higher level of pre-operative physical function measured using SF12Physical (PCSKnee; 27.9 ± 6.8 vs 26.8 ± 6.0, p = 0.008), they had a lower level of pre-operative mental health measured using SF12Mental (MCSKnee; 47.2 ± 12.0 vs 49.4 ± 11.6, p = 0.005) than the SESHigh category. Overall, the improvement in mental health (MCSKnee) post surgery was significantly greater for the SESLow (3.8 ± 12.9 vs 1.5 ± 12.2, p = 0.008) than the SESHigh category.

In linear regression modelling (Tables 4 and 5), SES score was not independently associated with post-operative IKSSPain, IKSSFunction or PCSKnee. However, there was a statistically significant inverse association between SES score and post-operative MCSKnee (coefficient −0.28, 95% CI: −0.52 to −0.04, p = 0.02), indicating that after adjustment for baseline MCSKnee, patients in lower socioeconomic groups tended to have better mental health scores post arthroplasty.

Regression models for IKSSPain

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative IKSSPain are presented in Table 4. Presence of complications, being a non-English speaker and having a higher burden of comorbidities were associated with lower post-operative IKSSPain score, i.e., more pain at 12 months. Having less pre-operative pain and less pre-operative physical impairment and mental distress were associated with higher post-operative IKSSPain score, i.e., less pain at 12 months.

Regression models for IKSSFunction

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative IKSSFunction are presented in Table 4. Female sex, older age, higher BMI, presence of a complication, being a non-English speaker, having a higher burden of comorbidities and lower pre-operative IKSSPain, were associated with lower IKSSFunction score i.e., worse function at 12 months. Having better function prior to surgery, a cruciate retaining procedure, and less pre-operative physical impairment and mental distress were associated with higher IKSSFunction score i.e., better function at 12 months.

Regression models for PCSKnee

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative PCSKnee are presented in Table 5. Presence of a complication and a higher burden of comorbidities were associated with worse physical health at 12 months post-op. Having a higher pre-operative IKSSFunction score, a cruciate retaining procedure, and better pre-operative physical and mental health were associated with better physical function at 12 months post arthroplasty.

Regression models for MCSKnee

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative MCSKnee are presented in Table 5. Complications and comorbidities were associated with worse mental health at 12 months. Older age at time of surgery, lower SES score and better pre-operative mental health were associated with better mental health at 12 months post arthroplasty.

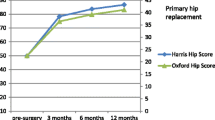

Hip arthroplasty analyses

Characteristics of the 835 patients who underwent THR are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Overall, these patients were similar in profile to those who had TKR, with several notable exceptions. There was a higher proportion of male patients (333 [39.9%]) and proportionately fewer obese patients (371 [44.4%]). In addition to OA, RA and AVN, 26 (3.1%) had THR for congenital hip dysplasia. Fewer patients had a prior contralateral arthroplasty (204 [24.4%]). Compared with patients undergoing TKR, those having THR had proportionately more post-operative complications 222 (26.6%), though most (118 of 222) of these were minor and did not require intervention or significantly impact length of stay. Overall, the complications were medical (n = 70), wound (n = 34) and orthopaedic (n = 19). The number of unplanned readmissions (46 [5.5%]) and additional unplanned procedures (36 [4.3%])) were both lower for those having THR. However, similar to those undergoing TKR, the most common indication for readmissions/unplanned procedures was wound complications.

Association of SES and hip arthroplasty

In univariate analysis (Table 3), there were no significant differences in most of the characteristics of patients in the SESLow compared with the SESHigh category. However, similar to the knee dataset, patients in the SESLow category had a higher level of pre-operative physical function (PCSHip; 26.9 ± 6.1 vs 25.9 ± 5.2, p = 0.012), and a significantly greater improvement in mental health (MCSHip) post arthroplasty than the SESHigh category (5.9 ± 13.3 vs 4.0 ± 12.7, p = 0.047).

In linear regression modelling (Tables 4 and 5), SES score was not independently associated with post-operative HHSPain, HHSFunction, PCSHip or MCSHip.

Regression models for HHSPain

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative HHSPain are presented in Table 4. Having a higher burden of comorbidities was associated with more pain at 12 months. Being older, having less pre-operative physical impairment and mental distress were associated with less pain at 12 months.

Regression models for HHSFunction

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative HHSFunction are presented in Table 4. Older age, higher BMI and a higher number of comorbidities were associated with worse function at 12 months. Having less pre-operative physical impairment or mental distress, better pre-operative function, and having a cemented THR were associated with better function at 12 months.

Regression models for PCSHip

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative PCSHip are presented in Table 5. Older age and a higher burden of comorbidities were associated with worse physical health at 12 months post arthroplasty. Having better pre-operative function, and physical and mental health were associated with better physical function at 12 months post arthroplasty.

Regression models for MCSHip

Results of linear regression modelling for independent determinants of post-operative MCSHip are presented in Table 5. Comorbidities were associated with worse mental health at 12 months post arthroplasty. Older age at time of surgery and better pre-operative physical and mental health were associated with better mental function at 12 months post arthroplasty.

Discussion

In an Australian setting, we have shown that SES is not an independent determinant of pain and functional outcomes post joint replacement surgery. We have confirmed several important predictors of pain and functional outcome of arthroplasty including age, BMI, comorbidities, pre-operative pain and function, and pre-operative mental health. We have also shown that relative to baseline, patients in lower socioeconomic groups have the greatest improvement in mental health post arthroplasty.

The lack of a predictive association between SES and several key arthroplasty outcome measures in our study contrasts the findings of most other investigators [10, 11, 13, 14]. A large UK study by Jenkins et.al using a SES classification system similar to the ABS ‘SES score’ , with comparable health questionnaires, showed significant differences in SF-36 physical improvement between the least and most “deprived groups” 18 months post THR [13]. A study based in Scotland by Clement et al. reported similar findings [11]. In a smaller study Allen-Butler et al. [10] conducted a secondary analysis of a prospective randomized study originally comparing 2 different hip stems. They also concluded that individual socioeconomic parameters such as education level, household income, as well as being African American were associated with lower Harris Hip Scores up to 2 years post THR [10]. Finally, a study by Schafer et al. also concluded that socioeconomic variables independently predicted response to THR [14].

Only one study to date has reported that lower SES did not appear to affect the outcome of joint replacement; this was a multicentre study conducted in several countries (USA, UK, AU, Canada) in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty [28]. SES data were derived from a pre-operative questionnaire regarding education, income, working status and living arrangements, to allow for direct comparison between countries. Despite reporting a correlation between lower income and worse pre-operative pain and function, there were no differences in post-operative pain and function at 24 months.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of association between SES and pain/function outcomes following arthroplasty in our study. The first relates to the differences in measures of SES used in the various studies to date. Although elements such as level of education and income are common to most measures of SES, there are possible regional differences in the components of this construct. Therefore, the use of the ABS ‘SES score’ , a composite or ‘global’ measure of SES specifically derived for use in Australia, is a methodological strength of our study. However, within each postal address code, there will likely be individuals who have a lower or higher SES than might be expected. While this is a possible limitation of our study, in the Australian population as a whole, the SES score is a reliable indicator of SES.

Although the median SES score among our patients was 7, over 30% (335 [33.0%] of patients undergoing knee replacement and 263 [31.5%] patients undergoing hip replacements) had a SES score of 5 or under, indicating that our centre serves a varied patient population, ranging from the lowest to highest SES.

Another possible explanation for our findings may be that unlike previous studies, our analyses accounted for multiple variables that are known to influence the outcome of arthroplasty. Previous studies have not reported such comprehensive demographic, surgical and outcome data.

A third possible explanation relates to the delivery of care in our centre. Geared towards the equitable delivery of health care to all, the Australian public health care system aims to optimize outcomes of elective surgery through pre-operative assessment and management of comorbidities, and a multi-disciplinary approach to post-operative care and discharge planning. Our results imply that in a specialized high through-put arthroplasty centre such as ours, which serves a diverse patient population, there is capacity to overcome the potential negative effects of socioeconomic disadvantage. This complements the observation that specialist arthroplasty centres report better patient outcomes overall, compared to non-specialist, low through-put centres [29–31].

One possible limitation of our study is that we did not include data for privately insured patients undergoing arthroplasty in the private sector. However, as there is likely to be less variation in SES in private Australian hospitals, with most patients being from high socioeconomic groups, it may not be possible to effectively assess the impact of SES on arthroplasty outcomes in such a setting.

In this study we assessed the post-operative ‘state’ of our patients relative to their pre-operative ‘state’ , by including baseline pain and function scores as covariates in our regression models. While it has been reported by some that those who have worse pain and functional status pre-surgery may experience greater change in scores compared to those who have better pre-surgery status, the literature is inconsistent and a smaller change in score on a fixed ended scale in those with a better pre-surgery status may also simply reflect a ceiling effect [32, 33]. Further it could be argued the actual post-operative status is more reflective of the benefit of surgery. Several of the studies cited above also assessed the post-operative status, relative to baseline [10, 28] while others chose to report the change in status [11, 13, 14]. When we performed the analyses using change in scores as the outcome, our findings remained in contrast to others, in that SES did not predict outcomes post-surgery.

While previous studies have indicated that lower socioeconomic status (SES) may be associated with worse outcomes post total knee (TKR) and hip (THR) replacement, we hypothesise that ‘due to differences in socio-economic fabric, ethnic composition, health care systems and cultural expectations, the relative importance of SES as a predictor of outcome post TKR and THR may differ among nations’. Indeed, ours is the first study to evaluate the association between SES and outcome of arthroplasty in the Australian public health care system. Our findings contrast those of most previous reports by showing that SES is not an independent predictor of arthroplasty outcome. Further, we show the novel finding that relative to baseline, patients with lower SES have greater mental health benefits post arthroplasty than their more privileged counterparts. Our results imply that in a specialised high through-put arthroplasty centre, which serves a diverse patient population, there is capacity to overcome the potential negative effects of socioeconomic disadvantage. This also complements the observation that specialist arthroplasty centres report better patient outcomes overall, compared to non-specialist, low through-put centres.

The only significant association of SES demonstrated in our study was an inverse correlation between SES score and the post-operative SF12 Mental Component Score among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty (MCSKnee). This suggests that compared with more privileged counterparts, those in lower socio-economic groups are even more likely to have higher – and better – post-operative mental health scores, relative to their baseline mental health scores. Arthroplasty has been shown to be a ‘life-changing’ procedure, with a substantial impact on the mental health of patients. In our study, the difference in the mental health gains of patients in low versus high socioeconomic groups may be related to differences in patient expectations and whether these expectations are met.

In this study we have identified several important predictors of outcome following large joint arthroplasty. Among patients undergoing TKR, female gender, higher BMI, limited English proficiency and a greater burden of comorbidities, were associated with worse pain and lower function at 12 months; we and others have identified these variables in prior research [4, 6, 34]. Pre-operative psychological state in particular appears to be an important determinant of pain and functional outcome in TKR [35]. Similar to TKR, important independent predictors of pain and function in THR were comorbidities, BMI and baseline physical and psychological health. Obesity and psychological distress are common in patients presenting for arthroplasty [5, 34–36], and studies are currently under way to evaluate the efficacy and cost effectiveness of mental health programs and obesity interventions in these patient groups [37–39].

In our study, the median post-operative PCSKnee was 37.1, meaning that half of our patients still had moderate to severe functional impairment following the procedure. These results are comparable to the findings of others [25]. Overall, the improvement in physical and mental health with THR, as measured by the SF-12, exceeded that seen with TKR. In addition to inherent differences between the two procedures, here we found that patients undergoing knee arthroplasty were more likely to be female, obese, hypertensive and non-English speaking, and to have previously had surgery on the contralateral side, than those undergoing hip arthroplasty. These findings may in part explain the differences observed in the outcomes of the two procedures.

Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that in a setting such as ours, underprivileged patients do as well in terms of pain and functional outcomes of arthroplasty, and may even have greater mental health gains than more privileged patients. Our findings further support efforts to ensure equity in access to arthroplasty among patients of all SES.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- AVN:

-

Avascular necrosis

- BMI:

-

Body masss index

- CCF:

-

Congestive cardiac failure

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CHD:

-

Congenital hip dysplasia

- COAD:

-

Chronic obstructive airways disease

- HHSPain:

-

Harris hip pain score

- HHSFunction:

-

Harris hip function score

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- IKSSPain:

-

International knee society pain score

- IKSSFunction:

-

International knee society function score

- MCS:

-

Short form 12 mental component score

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PCS:

-

Short form 12 physical component score

- Pre-op:

-

Pre-operative

- Post-op:

-

Post-operative

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status.

References

Dixon T, Shaw M, Ebrahim S, Dieppe P: Trends in hip and knee joint replacement: socioeconomic inequalities and projections of need. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63 (7): 825-830. 10.1136/ard.2003.012724.

Kim S: Changes in surgical loads and economic burden of hip and knee replacements in the US: 1997–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59 (4): 481-488. 10.1002/art.23525.

Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Repor. 2010, Adelaide: AOA,https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/,

Dowsey MM, Broadhead ML, Stoney JD, Choong PF: Outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in English- versus non-English-speaking patients. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2009, 17 (3): 305-309.

Dowsey MM, Choong PF: Early outcomes and complications following joint arthroplasty in obese patients: a review of the published reports. ANZ J Surg. 2008, 78 (6): 439-444. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04554.x.

Gandhi R, Dhotar H, Razak F, Tso P, Davey JR, Mahomed NN: Predicting the longer term outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2010, 17 (1): 15-18. 10.1016/j.knee.2009.06.003.

Kennedy DM, Hanna SE, Stratford PW, Wessel J, Gollish JD: Preoperative function and gender predict pattern of functional recovery after hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006, 21 (4): 559-566. 10.1016/j.arth.2005.07.010.

Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB: Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004, 86-A (10): 2179-2186.

Agabiti N, Picciotto S, Cesaroni G, Bisanti L, Forastiere F, Onorati R, Pacelli B, Pandolfi P, Russo A, Spadea T, Perucci C, on behalf of the Italian Study Group on Inequalities in Health Care: The influence of socioeconomic status on utilization and outcomes of elective total hip replacement: a multicity population-based longitudinal study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007, 19 (1): 37-44.

Allen Butler R, Rosenzweig S, Myers L, Barrack RL: The Frank Stinchfield award: the impact of socioeconomic factors on outcome after THA: a prospective, randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011, 469 (2): 339-347. 10.1007/s11999-010-1519-x.

Clement ND, Muzammil A, Macdonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC: Socioeconomic status affects the early outcome of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011, 93 (4): 464-469.

Hollowell J, Grocott MP, Hardy R, Haddad FS, Mythen MG, Raine R: Major elective joint replacement surgery: socioeconomic variations in surgical risk, postoperative morbidity and length of stay. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010, 16 (3): 529-538.

Jenkins PJ, Perry PR, Yew Ng C, Ballantyne JA: Deprivation influences the functional outcome from total hip arthroplasty. Surgeon. 2009, 7 (6): 351-356. 10.1016/S1479-666X(09)80109-1.

Schafer T, Krummenauer F, Mettelsiefen J, Kirschner S, Gunther KP: Social, educational, and occupational predictors of total hip replacement outcome. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010, 18 (8): 1036-1042. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.003.

Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN: Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989, 248: 13-14.

Harris WH: Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1969, 51 (4): 737-755.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996, 34 (3): 220-233. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) - Technical Paper. 2006, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987, 40 (5): 373-383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8.

Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, Jani AB, Vijayakumar S: An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer. 2004, 4: 94-10.1186/1471-2407-4-94.

Davies AP: Rating systems for total knee replacement. Knee. 2002, 9 (4): 261-266. 10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00095-9.

Bach CM, Nogler M, Steingruber IE, Ogon M, Wimmer C, Gobel G, Krismer M: Scoring systems in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002, 399: 184-196.

Andrews G: A brief integer scorer for the SF-12: validity of the brief scorer in Australian community and clinic settings. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002, 26 (6): 508-510. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00357.x.

Lee A, Browne MO, Villanueva E: Consequences of using SF-12 and RAND-12 when examining levels of well-being and psychological distress. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008, 42 (4): 315-323. 10.1080/00048670701881579.

Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L: Appropriate questionnaires for knee arthroplasty. Results of a survey of 3600 patients from the swedish knee arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001, 83 (3): 339-344. 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.11134.

Ostendorf M, van Stel HF, Buskens E, Schrijvers AJ, Marting LN, Verbout AJ, Dhert WJ: Patient-reported outcome in total hip replacement. A comparison of five instruments of health status. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004, 86 (6): 801-808. 10.1302/0301-620X.86B6.14950.

Sanderson K, Andrews G: The SF-12 in the Australian population: cross-validation of item selection. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002, 26 (4): 343-345. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00182.x.

Davis ET, Lingard EA, Schemitsch EH, Waddell JP: Effects of socioeconomic status on patients’ outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008, 20 (1): 40-46.

Katz JN, Losina E, Barrett J, Phillips CB, Mahomed NN, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Harris WH, Poss R, Baron JA: Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001, 83-A (11): 1622-1629.

Katz JN, Phillips CB, Baron JA, Fossel AH, Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Lingard EA, Harris WH, Poss R, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Wright EA, Losina E: Association of hospital and surgeon volume of total hip replacement with functional status and satisfaction three years following surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48 (2): 560-568. 10.1002/art.10754.

Katz JN, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Barrett JA, Fossel AH, Creel AH, Wright J, Wright EA, Losina E: Association of hospital and surgeon procedure volume with patient-centered outcomes of total knee replacement in a population-based cohort of patients age 65 years and older. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56 (2): 568-574. 10.1002/art.22333.

Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY: Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004, 86-A (5): 963-974.

Fortin PR, Clarke AE, Joseph L, Liang MH, Tanzer M, Ferland D, Phillips C, Partridge AJ, Belisle P, Fossel AH, Mahomed N, Sledge CB, Katz JN: Outcomes of total hip and knee replacement: preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at six months after surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42 (8): 1722-1728. 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1722::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-R.

Dowsey MM, Liew D, Stoney JD, Choong PF: The impact of pre-operative obesity on weight change and outcome in total knee replacement: a prospective study of 529 consecutive patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010, 92 (4): 513-520.

Paulsen MG, Dowsey MM, Castle D, Choong PFM: Preoperative psychological distress and functional outcome after knee replacement. ANZ J Surg. 2011, 81 (10): 681-687. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05634.x.

Singh JA, Lewallen D: Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary total hip arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010, 11: 90-10.1186/1471-2474-11-90.

Dowsey MM, Liew D, Choong PF: The economic burden of obesity in primary total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011, 63 (10): 1375-1381. 10.1002/acr.20563.

Grossman P, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U, Raysz A, Kesper U: Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychother Psychosom. 2007, 76 (4): 226-233. 10.1159/000101501.

Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassario P, Tennen H, Finan P, Kratz A, Parrish B, Irwin MR: Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008, 76 (3): 408-421.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/148/prepub

Acknowledgements

Dr Dowsey holds an NHMRC Early Career Australian Clinical Fellowship (APP1035810). Dr Nikpour holds an NHMRC Early Career Australian Clinical Fellowship (APP1071735).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MMD contributed to study design, data collection, interpretation of findings and preparation of the manuscript. MN contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation of findings and preparation of the manuscript. PFMC contributed to study design, data collection, interpretation of findings and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Michelle M Dowsey, Mandana Nikpour contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12891_2013_2102_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1:Predictors of change in Pain, Function and Quality of Life Scores 12 months large joint arthroplasty.(DOCX 29 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dowsey, M.M., Nikpour, M. & Choong, P.F. Outcomes following large joint arthroplasty: does socio-economic status matter?. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15, 148 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-148

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-148