Abstract

Background

Adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ADSCs), a type of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have great potential as therapeutic agents in regenerative medicine. Numerous animal studies have documented the multipotency of ADSCs, showing their capabilities to differentiate into tissues such as muscle, bone, cartilage, and tendon. However, the safety of autologous ADSC injections into human joints is only beginning to be understood and the data are lacking.

Methods

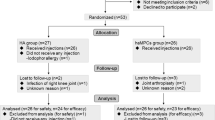

Between 2009 and 2010, 91 patients were treated with autologous ADSCs with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for various orthopedic conditions. Stem cells in the form of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) were injected with PRP into various joints (n = 100). All patients were followed for symptom improvement with visual analog score (VAS) at one month and three months. Approximately one third of the patients were followed up with third month magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the injected sites. All patients were followed up by telephone questionnaires every six months for up to 30 months.

Results

The mean follow-up time for all patients was 26.62 ± 0.32 months. The follow-up time for patients who were treated in 2009 and early 2010 was close to three years. The relative mean VAS of patients at the end of one month follow-up was 6.55 ± 0.32, and at the end of three months follow-up was 4.43 ± 0.41. Post-procedure MRIs performed on one third of the patients at three months failed to demonstrate any tumor formation at the implant sites. Further, no tumor formation was reported in telephone long-term follow-ups. However, swelling of injected joints was common and was thought to be associated with death of stem cells. Also, tenosinovitis and tendonitis in elderly patients, all of which were either self-limited or were remedied with simple therapeutic measures, were common as well.

Conclusions

Using both MRI tracking and telephone follow ups in 100 joints in 91 patients treated, no neoplastic complications were detected at any ADSC implantation sites. Based on our longitudinal cohort, the autologous and uncultured ADSCs/PRP therapy in the form of SVF could be considered to be safe when used as percutaneous local injections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), including ADSCs, have great potentials as a future therapeutic agent in the field of regenerative medicine. This has created much in vitro[1–3], in vivo[4–14], and clinical [15–26] experimentations on MSCs. MSCs can be readily extracted from bone marrow of hip and spine, and adipose tissue of abdomen, thigh and hips [27, 28]. These extracted MSCs have potentials to differentiate into bone, cartilage, tendon, muscle, and other tissues [15–17]. Such capabilities of MSCs to differentiate into bones and cartilage have been documented by numerous animal studies [9–14]. Also, there have been few reports of successful regeneration of bone and cartilage in humans by using various MSCs [16–26], particularly ADSCs [19–23].

\The platelets contain critical growth factors and mediators of tissue repair pathways. Activation of platelets with calcium chloride has been shown to induce immediate platelet growth factor release in vitro[29]. The platelet rich plasma (PRP) obtained from autologous blood contains a high concentration of stored autologous growth factors. By exposing PRP to calcium chloride, degranulation of platelet is induced. PRP has been successfully used as a cell culture additive to facilitate growth and differentiation of autologous MSCs [30–33].

However, the safety data for using the autologous MSC therapy is lacking. Although Centeno et al. has reported safety and complication rate of using autologous bone marrow derived stem cells in orthopedic applications [34], there has not been any safety report on using ADSCs for human orthopedic applications. One of the safety issues that need to be addressed is the potential of these stem cells becoming neoplasms. This concern was brought on by reports of chromosomal abnormalities in MSCs (not including ADSCs) that have been cultured in vitro[35–38]. However, when these cells are cultured less than 60 days in vitro, they pose no detectable risk of cell mutation or tumor formation, as previously reported [39]. Further, autologous MSCs that have been used for cartilage repair in humans also indicate that they form no tumors during long-term follow-up [26]. The few early human clinical trials using MSCs completed thus far support the conclusion that MSCs are safe as therapeutic agents [30, 34, 40]. However, these MSCs were not including ADSCs.

The purpose of this study was to examine the safety profile of ADSCs along with PRP for human orthopedic applications into articular joints.

Methods

In 2009, Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) has approved medical uses of autologous ADSCs with minimal manipulation [41]. From November 2009 until December 2010, 91 patients with 100 articular joints were treated with autologous ADSCs in the form of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) along with autologous PRP. The mixture of ADSCs and PRP were percutaneously injected into knees, hips, low backs, and ankles. After the completion of the treatment, all patients were followed for three months. At the third month, some of the patients were also followed up with high field MRI of the implant sites. Afterwards, all patients were followed up with telephone questionnaires every six months: at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months.

This study was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and regulation guidelines of KFDA. The written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from participants. According to Korean law (Rules and Regulations of the Korean Food and Drug Administration), questionnaire and register based studies do not need approval by ethical and scientific committees, and do not require informed consent [41]. All data was de-identified and analyzed anonymously.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria and outcome endpoints of patients

For all patients, aspirin, NSAIDS, or any other form of anticoagulant therapy were stopped at least seven days prior to liposuction and resumed one week after. Aspirin were continued to be withheld until the last day of PRP injection.

The inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and outcome endpoints were listed as follows: Inclusion criteria: (i) age 18 and older; (ii) chronic or degenerative joint disease causing significant functional disability and/or pain; (iii) the failure of conservative treatments; and (iv) an unwillingness to proceed with surgical intervention.

Exclusion criteria: (i) active inflammatory or connective tissue disease thought to impact pain condition (i.e., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia); (ii) active non-corrected endocrine disorder that might impact pain condition (i.e., hypothyroidism and diabetes); (iii) active neurologic disorder that might impact pain condition (i.e., peripheral neuropathy and multiple sclerosis); (iv) pulmonary and cardiac disease uncontrolled with medication usage; (v) history of active neoplasm within the past five years; (vi) blood disorders documented by abnormal complete blood count (CBC) within three months including severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis and/or leukopenenia; and (vii) medical conditions precluding the injection procedures.

Outcome endpoints (pain score, imaging, and telephone questionnaires): (i) pre-treatment visual analog scale (VAS); (ii) VAS at one month after the procedure; (iii) VAS at three months after the procedure; (iv) MRI imaging within three months before the ADSC injection procedure; and (v) MRI imaging at three months after the procedure; (vi) telephone questionnaires every six months: at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months.

Liposuction procedure

Patients were restricted from taking corticosteroids, aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and oriental herb medications for minimum one week prior to the liposuction.

For the liposuction procedure, the patients were sedated with propofol 2 mg IV push and 20–30 mg/h rate of continuous infusion.

Using tumescent solution (40 mL of lidocaine [20 g/L] with 20 mL of Marcaine [5 g/L], 500 mL normal saline, and 0.5 mL of epinephrine 1:1000), the lower abdomen area was anesthetized. Next, lipoaspirates were extracted and separated by gravity. The resulting 100 mL of adipose tissue with the tumescent solution were then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 minutes. The end result was approximately 40 mL of packed adipose tissue, fibrous tissue, red blood cells and a small number of nucleated cells. An equal volume of digestive enzyme (0.07% type 1 collagenase; Adilase, Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA) was then mixed with the centrifuged lipoaspirates at a ratio of 1:1. The mixture was then digested for 30 min at 37°C while rotating. After the digestion, the lipoaspirates were centrifuged at 100 g for 3 minutes to separate the lipoaspirate and the enzyme. The left-over enzyme was then removed.

Using 5% dextrose in lactated Ringer’s solution (D5LR), the lipoaspirates were washed three times to remove the collagenase. After each washing, the lipoaspirates were centrifuged at 100 g. After the last centrifuge, approximately 10 mL of ADSCs-containing SVF were obtained [28].

PRP preparation

While preparing the ADSCs, 30 mL of autologous blood was drawn with 2.5 mL anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution (0.8% citric acid, 0.22% sodium citrate, and 0.223% dextrose; Baxter Healthcare Corp., Marion, NC, USA). This was centrifuged at 200 g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was drawn and spun at 1000 g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was drawn and discarded. The resulting 2 mL buffy coat (PRP) was mixed with 10 mL of ADSCs-containing SVF. To this mixture, 0.5% (w/v) hyaluronic acid (1 mL; Huons, Chungbuk, Korea) was added as a scaffold. This mixture was again mixed with CaCl2 at a ratio of 10:2 (PRP to CaCl2) for activation of the platelets. This autologous PRP mixture was freshly prepared on the same day of liposuction. Afterwards, when patient visited for weekly PRP injection, it was freshly prepared each time.

ADSCs injection with PRP

On the day of liposuction, ADSCs and PRP were prepared within the same surgical procedure. In order to inject ADSCs with PRP, the patients’ joints were prepared by sterile technique and were anesthetized with 2% lidocaine. Then, the mixture of ADSCs, PRP, hyaluronic acid, and CaCl2 was injected into the joint under the ultrasound guidance at an aseptic room.

The patients were then instructed to remain still for 30 minutes to allow for cell attachment. As they were discharged to home, the patients were instructed to maintain activity as tolerated.

The patients returned for four additional autologous PRP injections that were freshly prepared with CaCl2 each week over one month period.

The follow-up disease surveillance questionnaires

All patients were followed up with telephone questionnaires every six months: at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months. Each time, patients were asked the following questions: (i) did you experience any complications (i.e., infection, illness, etc.) you believe may be due to the procedure? If yes or maybe, please explain; and (ii) have you been diagnosed with any form of cancer since the procedure? If yes, please explain.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., New York, USA). There were three groups (pre-treatment, one month after treatment, and three months after treatment) and Levene’s test results revealed that the variance of the dependent variable (relative VAS) was not equal across groups. Therefore, Kruskall-Wallis test was conducted to compare the means of three groups. To detect significant differences among groups, post hoc testing was performed by Mann–Whitney U tests. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and areas treated

From November 18, 2009 until December 17, 2010, a total of 100 joints were treated in 91 patients. As of October 2012, the mean follow-up time for all patients was 26.62 ± 0.32 months. 100 procedure follow-up contacts occurred at 12 months or more, 78 contacts at 24 months or more, and 17 contacts at 30 months (Table 1). The first patient was treated on November 18, 2009. Thus, the follow-up time for patients who were treated in 2009 and early 2010 was close to three years.

There were a total of four patients in 2009. They were all female and their age was 61, 57, 71, and 77, respectively. Of these four, the first patient received two injections of ADSCs into the knee: the first dose was injected on November 18, 2009, and the second dose was injected on April 28, 2010. The first dose of the first patient did not include PRP. Thus, the procedure was repeated on April 28, 2010 with PRP and ADSCs. Of the total of 91 patients, three patients received two treatments of identical joints and six patients received two treatments at different joints. Nine patients underwent two procedures. Of the nine, three patients received ADSCs on the same knee joints and the other six patients received ADSCs on the other knees. The second procedure of all nine patients occurred with 3 ~ 4 months after the first. Of these nine patients, only one patient did not obtain MRI after the first and second doses of ADSCs. All other eight patients obtained MRI after three months from each first and second ADSCs/ PRP treatment. Thus, the total number of joints treated (n = 100) is higher than the number of patients (n = 91) treated. The mean age was 51.23 ± 1.50, with the range being 18–78 years; 45 patients were male and 46 female. The age of patients was relatively evenly distributed (Table 1). Nine patients underwent more than one procedure. In all, the patients underwent 74 knee procedures (distributed with 67.6% in the age range of 40 ~ 69), 22 hip procedures (distributed with 81.8% in the age range of 18 ~ 49), two low back procedures, and two ankle procedures (Table 2). Of the 22 hip procedures, 15 were avascular necrosis and seven were hip osteoarthritis. All 74 knees and two ankles had diagnosis of osteoarthritis while the two low back procedures had spinal disc herniation.

Pre-procedure MRIs were carried out on 86 patients. Among these, 27 patients also underwent post-procedure MRIs. Due to financial reasons, 59 patients refused to undergo post-procedure MRIs. Mean time for last MRI follow-up since the procedure was 3.11 ± 0.12 months. MRIs (as read by both examiners and physicians) were negative for any evidence of tumor formation at the implantation site.

Pain measurements

To assess the symptom improvement of the treatment, VAS was analyzed. For all patients, VAS was marked at 10 before treatments. The patients were followed up consequently with VAS at one month and at three months after the initial injection. Thus, the VAS results are relative to the VAS marked before the initial ADSCs-containing SVF injections.

The relative mean VAS of 96 joints at the end of one month follow-up was 6.55 ± 0.32, and at the end of three months follow-up was 4.43 ± 0.41 (Figure 1). The relative mean VAS of cartilage repair of 81 joints (74 knees and seven hips; excluding two ankles and two low backs) at the end of one month follow-up was 6.53 ± 0.63 and at the end of three months follow-up was 4.30 ± 0.74 (Figure 1). The lowest values of the relative mean VAS were in the age range group of 70 ~ 80 (Table 3). The relative mean VAS of bone regeneration (n = 15) in hips of AVN patients at end of one month follow-up was 6.64 ± 0.32 and at end of three months follow-up was 5.17 ± 0.32 (Figure 1). Two low back and ankle patients reported minimal clinical improvement and did not obtain post procedure MRIs.

Pain measurements of patients. VAS and AVN are visual analog scale and avascular necrosis, respectively. Combined relative mean VAS scores (right three bars) are those of 96 joints (hip bone [left bars]: 15 joints; knee and hip cartilage [middle bars]: 81 joints). Error bars indicate standard errors. * = p < 0.05.

Complications reporting

The complications of the concern can be summarized as follows: (i) pain and swelling: 37% of 100 joints treated joints reported development of pain and swelling after one day after the ADSCs/PRP injection. Pain swelling improved with cold compressions and routine oral NSAIDs prescriptions given on the first day of discharge. These complications were detected only in the knee joints treated. Among these patients, 51% were older than 50; (ii) infection: 0%; (iii) neurologic: 1% (a hemorrhagic stroke approximately two weeks after the procedure); (iv) tumor: 0%: (v) tendonitis/tenosynovitis: 22%. Among these patients, 68% were older than 60 and started to occur after 6 ~ 8 weeks of the procedure; and (vi) skin: 1% (a localized rash around the injection site after 1 ~ 2 days of the procedure) (Table 4).

Discussion

Our results show that autologous and uncultured ADSCs/PRP therapy in the form of SVF could be considered to be safe when used as percutaneous local injections.

ADSCs were extracted using collagenases, which were later removed by washing the ADSCs with D5LR solution three times. After all three washings, the total amount of collagenase contained in the ADSCs was undetectable (data not shown). Therefore, it would be very doubtful if such undetectable amount of collagenase would have caused swelling and pain of the joints. However, it can be assumed that some of the cells injected into the joints, including red blood cells and ADSCs, would not have survived, as previously reported [42]. Probably such non-viable cells surmount an inflammatory reaction, causing pain and swelling. A recent report supports this notion [43]. Such pain and swelling subside gradually with oral intakes of NSAIDs and cold compression. The frequency of these complications was more than that of other report using culture-expanded bone marrow-derived MSCs [34].

After 6–8 weeks of ADSCs and PRP injection of knee joints, some elderly patients complained of knee pain secondary to tenosinovitis and tendonitis. These symptoms usually occurred in elderly patients over the age of 60 (15 of 22 patients), as previously described [44]. These symptoms improved with NSAIDs and resolved with trigger point injections with triamcinolone at third or fourth months. The exact cause of these symptoms is not clear. It can be postulated that knee posture may be the cause. Cartilage regeneration, decreased mobility during the procedure, or increased mobility after the procedure may cause the positioning of the knee joint to be changed, resulting the tendons and ligament to strain, as previously reported [45].

One patient experienced a localized rash around the injected site of the knee. Another patient experienced a hemorrhagic stroke. Although the percentage of these complications is greater than 1% of the total patient population of this group, these two are more of co-incidences. The likely causative agent in case of the localized rash would be the synthetic hyaluronic acid that was injected as a scaffold material. As for the hemorrhagic stroke, no other patient experienced such symptoms in the other patient group treated after the year 2010. Further, in the case of hemorrhagic stroke, it is difficult to assume that any form of cells injected locally with PRP were re-absorbed or transferred to blood stream, causing hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, recent research by Horie et al. demonstrated that MSCs implanted in a joint remain localized to the transplant site [46].

According to the results of the analysis of pain scores and telephone questionnaires from 100 joints, there has been no report of tumor formation at the implant sites. Further, there was no evidence of tumor formation in 27 joints that were imaged by MRI. This study is the first report on ADSCs safety in clinical applications. While it is possible that tumors may still form at some time beyond the average follow-up period presented in our data, this possibility decreases at an exponential rate. MSCs replicate every 2–4 days in vitro expansion [35–37]. Thus, if a tumor were to form at the implanted site, it might have been discernible within few months by a high field MRI.

Patients’ VAS after the ADSCs/PRP treatment improved 50-60%, and this was statistically significant (Figure 1). The pain improvement can be attributed to the probable regeneration of the damaged tissues that have been documented by MRI in some of the patients. However, no patient reported 100% resolution of the pain. Many possibilities exist for the explanation of incomplete resolution of the pain. One of the reasons would be the fact that the extent of the regeneration was achieved only partially. Another possible rationale for the incomplete resolution of the pain is probably the fact that the osteoarthritis and AVN are joint disorders as a whole, not just degeneration of only cartilage and bone, respectively.

The two low back and the two ankle patients reported minimal clinical improvement. Many reasons exist for possible rationale of the minimal pain improvement. Also, quantity and quality of MSCs are important. Another important factor is properly targeting the site for injection [46], especially if the target site has limited space. With regards to low backs, uncertainty exists if ADSCs were correctly and properly placed in the disc. As for the ankle, the quantity and quality of ADSCs injected in the limited joint space could be questioned.

Overall, this study with 100 joint injections of ADSCs, in the form of SVF, with PRP shows that ADSCs/PRP treatment is safe and provides long-term pain improvement. However, this study only shows a glimpse of the possibility of using ADSCs in the field of regenerative medicine. All patients were offered the third month post-procedure MRIs, but some patients refused to undergo post-procedure MRIs due to symptom improvement and/or financial reasons. Therefore, the longer-term (more than 3 months) follow-ups were conducted based on telephone questionnaires. The measurement of PRP concentration and the assessment of viable ADSCs’ quantity and quality are necessary. Also, randomized, double blind, and placebo-controlled studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of ADSCs in various joint diseases.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated no evidence of neoplastic complications in any implant sites in 91 patients with 100 joints, some of whom were monitored with high field MRI tracking and via general surveillance. In summary, based on this longitudinal cohort, autologous and uncultured ADSCs/PRP therapy in the form of SVF can be considered to be safe when used as percutaneous local injections.

Abbreviations

- ADSC:

-

Adipose tissue-derived stem cell

- MSC:

-

Mesenchymal stem cell

- PRP:

-

Platelet-rich plasma

- SVF:

-

Stromal vascular fraction

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging.

References

Ando W, Tateishi K, Hart DA, Katakai D, Tanaka Y, Nakata K, Hashimoto J, Fujie H, Shino K, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura N: Cartilage repair using an in vitro generated scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from porcine synovial mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2007, 28: 5462-5470. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.030.

Ando W, Tateishi K, Katakai D, Hart DA, Hiquchi C, Nakata K, Hashimoto J, Fujie H, Shino K, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura N: In vitro generation of a scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct (TEC) derived from human synovial mesenchymal stem cells: biological and mechanical properties, and further chondrogenic potential. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008, 14: 2041-2049. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0015.

Tallheden T, Dennis JE, Lennon DP, Sjoqren-Jansson E, Caplan AI, Lindahl A: Phenotypic plasticity of human articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003, 85-A (Suppl): 93-100.

Nevo Z, Robinson D, Horowitz S, Hasharoni A, Yayon A: The manipulated mesenchymal stem cells in regenerated skeletal tissues. Cell Transplant. 1998, 7: 63-70. 10.1016/S0963-6897(97)00066-3.

Bielby R, Jones E, McGonagle D: The role of mesenchymal stem cells in maintenance and repair of bone. Injury. 2007, 38 (Suppl): 26-32.

Wakitani S, Goto T, Pineda SJ, Young RG, Mansour JM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM: Mesenchymal cell-based repair of large, full-thickness defects of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994, 76: 579-592.

Sakai D, Mochida J, Yamamoto Y, Nomura T, Okuma M, Nishimura K, Nakai T, Ando K, Hotta T: Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells embedded in Atelocollagen gel to the intervertebral disc: a potential therapeutic model for disc degeneration. Biomaterials. 2003, 24: 3531-3541. 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00222-9.

Johnstone B, Yoo JU: Autologous mesenchymal progenitor cells in articular cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999, 367 (Suppl): 156-162.

Agung M, Ochi M, Yanada S, Adachi N, Izuta Y, Yamasaki T, Toda K: Mobilization of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells into the injured tissues after intraarticular injection and their contribution to tissue regeneration. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006, 14: 1307-1314. 10.1007/s00167-006-0124-8.

Sakai D, Mochida J, Iwashina T, Watanabe T, Nakai T, Ando K, Hotta T: Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells transplanted to a rabbit degenerative disc model: potential and limitations for stem cell therapy in disc regeneration. Spine. 2005, 30: 2379-2387. 10.1097/01.brs.0000184365.28481.e3.

Walsh CJ, Goodman D, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM: Meniscus regeneration in a rabbit partial meniscectomy model. Tissue Eng. 1999, 5: 327-337. 10.1089/ten.1999.5.327.

Nishimori M, Deie M, Kanaya A, Exham H, Adachi N, Ochi M: Repair of chronic osteochondral defects in the rat. A bone marrow-stimulating procedure enhanced by cultured allogenic bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006, 88: 1236-1244.

Yamasaki T, Deie M, Shinomiya R, Izuta Y, Yasunaqa Y, Yanada S, Sharman P, Ochi M: Meniscal regeneration using tissue engineering with a scaffold derived from a rat meniscus and mesenchymal stromal cells derived from rat bone marrow. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005, 75: 23-30.

Kanaya A, Deie M, Adachi N, Nishimori M, Yanada S, Ochi M: Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stromal cells in partially torn anterior cruciate ligaments in a rat model. Arthroscopy. 2007, 23: 610-617. 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.01.013.

Barry FP: Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in joint disease. Novartis Found Symp. 2003, 249: 86-96.

Centeno CJ, Kisiday J, Freeman M, Schultz JR: Partial regeneration of the human hip via autologous bone marrow nucleated cell transfer: a case study. Pain Physician. 2006, 9: 253-256.

Centeno CJ, Busse D, Kisiday J, Keohan C, Freeman M, Karli D: Regeneration of meniscus cartilage in a knee treated with percutaneously implanted autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Med Hypotheses. 2008, 71: 900-908. 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.06.042.

Giannini S, Buda R, Cavallo M, Ruffilli A, Cenacchi A, Cavallo C, Vannini F: Cartilage repair evolution in post-traumatic osteochondral lesions of the talus: from open field autologous chondrocyte to bone-marrow-derived cells transplantation. Injury. 2010, 41: 1196-1203. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.09.028.

Pak J: Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells induce persistent bone-like tissue in osteonecrotic femoral heads. Pain Physician. 2012, 15: 75-85.

Pak J, Lee JH, Lee SH: A novel biological approach to treat chondromalacia patellae. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e64569-10.1371/journal.pone.0064569.

Kulakov AA, Goldshtein DV, Grigoryan AS, Rzhaninova AA, Alekseeva IS, Arutyunyan IV, Volkov AV: Clinical study of the efficiency of combined cell transplant on the basis of multipotent mesenchymal stromal adipose tissue cells in patients with pronounced deficit of the maxillary and mandibulary bone tissue. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2008, 146: 522-525. 10.1007/s10517-009-0322-8.

Mesimäki K, Lindroos B, Törnwall J, Mauno J, Lindqvist C, Kontio R, Miettinen S, Suuronen R: Novel maxillary reconstruction with ectopic bone formationby GMP adipose stem cells. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 38: 201-209. 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.01.001.

Taylor JA: Bilateral orbitozygomatic reconstruction with tissue-engineered bone. J Craniofac Surg. 2010, 21: 1612-1614. 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181edc829.

Kuroda R, Ishida K, Matsumoto T, Akisue T, Fujioka H, Mizuno K, Ohgushi H, Wakitani S, Kurosaka M: Treatment of a full-thickness articular cartilage defect in the femoral condyle of an athlete with autologous bone marrow-stromal cells. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007, 15: 226-231. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.008.

Slynarski K, Deszczynski J, Karpinski J: Fresh bone marrow and periosteum transplantation for cartilage defects of the knee. Transplant Proc. 2006, 38: 318-319. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.12.075.

Wakitani S, Okabe T, Horibe S, Mitsuoka T, Saito M, Koyama T, Nawata M, Tensho K, Kato H, Uematsu K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S, Hattori K, Ohgushi H: Safety of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cartilage repair in 41 patients with 45 joints followed for up to 11 years and 5 months. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011, 5: 146-150. 10.1002/term.299.

Caplan AI: Mesenchymal stem cell. J Orthop Res. 1991, 9: 641-650. 10.1002/jor.1100090504.

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, Fraser JK, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH: Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002, 13: 4279-4295. 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105.

Martineau I, Lacoste E, Gagnon G: Effects of calcium and thrombin on growth factor release from platelet concentrates: kinetics and regulation of endothelial cell proliferation. Biomaterials. 2004, 25: 4489-4502. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.013.

Doucet C, Ernou I, Zhang Y, Llense JR, Begot L, Holy X, Lataillade JJ: Platelet lysates promote mesenchymal stem cell expansion: a safety substitute for animal serum in cell-based therapy applications. J Cell Physiol. 2005, 205: 228-236. 10.1002/jcp.20391.

Bernardo ME, Avanzini MA, Perotti C, Cometa AM, Moretta A, Lenta E, Del Fante C, Novara F, de Silvestri A, Amendola G, Zuffardi O, Maccario R, Locatelli F: Optimization of in vitro expansion of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells for cell-therapy approaches: further insights in the search for a fetal calf serum substitute. J Cell Physiol. 2007, 211: 121-130. 10.1002/jcp.20911.

Müller I, Kordowich S, Holzwarth C, Spa-no C, Isensee G, Staiber A, Viebahn S, Gieseke F, Langer H, Gawaz MP, Horwitz EM, Conte P, Handgretinger R, Dominici M: Animal serum-free culture conditions for isolation and expansion of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells from human BM. Cytotherapy. 2006, 8: 437-444. 10.1080/14653240600920782.

Schallmoser K, Bartmann C, Rohde E, Reinisch A, Kashofer K, Stadelmeyer E, Drexler C, Lanzer G, Linkesch W, Strunk D: Human platelet lysate can replace fetal bovine serum for clinical-scale expansion of functional mesenchymal stromal cells. Transfusion. 2007, 47: 1436-1446. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01220.x.

Centeno CJ, Schultz JR, Cheever M, Robinson B, Freeman M, Marasco W: Safety and complications reporting on the re-implantation of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells using autologous platelet lysate technique. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010, 5: 81-93. 10.2174/157488810790442796.

Miura M, Miura Y, Padilla-Nash HM, Molinolo AA, Fu B, Patel V, Seo BM, Sonoyama W, Zheng JJ, Baker CC, Chen W, Ried T, Shi S: Accumulated chromosomal instability in murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells leads to malignant transformation. Stem Cells. 2006, 24: 1095-1103. 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0403.

Bochkov NP, Voronina ES, Kosyakova NV, Liehr T, Rzhaninova AA, Katosova LD, Platonova VI, Gol’dshtein DV: Chromosome variability of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2007, 143: 122-126. 10.1007/s10517-007-0031-0.

Izadpanah R, Kaushal D, Kriedt C, Tsien F, Patel B, Dufour J, Bunnell BA: Long-term in vitro expansion alters the biology of adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68: 4229-4238. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5272.

Bernardo ME, Zaffaroni N, Novara F, Cometa AM, Avanzini MA, Moretta A, Montaqna D, Maccario R, Villa R, Daidone MG, Zuffardi O, Locatelli F: Human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells do not undergo transformation after long-term in vitro culture and do not exhibit telomere maintenance mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2007, 67: 9142-9149. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4690.

Vacanti V, Kong E, Suzuki G, Sato K, Canty JM, Lee T: Phenotypic changes of adult porcine mesenchymal stem cells induced by prolonged passaging in culture. J Cell Physiol. 2005, 205: 194-201. 10.1002/jcp.20376.

Amrani DL, Port S: Cardiovascular disease: potential impact of stem cell therapy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2003, 1: 453-461. 10.1586/14779072.1.3.453.

Korean Food and Drug Administration: Cell therapy: Rules and Regulations, Chapter 2, Section 14. 2009, Seoul (Korea): The Organization

Fan W, Cheng K, Qin X, Narsinh KH, Wang S, Hu S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Wu JC, Xiong L, Cao F: mTORC1 and mTORC2 play different roles in the functional survival of transplanted adipose-derived stromal cells in hindlimb ischemic mice via regulating inflammation in vivo. Stem Cells. 2013, 31: 203-214. 10.1002/stem.1265.

Rock KL, Kono H: The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008, 3: 99-126. 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151456.

Halperin N, Axer A: The painful semimembranosus syndrome. Harefuah. 1978, 94: 329-330.

Almekinders LC, Vellema JH, PS : Strain patterns in the patellar tendon and the implications for patellar tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002, 10: 2-5. 10.1007/s001670100224.

Horie M, Sekiya I, Muneta T, Ichinose S, Matsumoto K, Saito H, Murakami T, Kobayashi E: Intra-articular Injected synovial stem cells differentiate into meniscal cells directly and promote meniscal regeneration without mobilization to distant organs in rat massive meniscal defect. Stem Cells. 2009, 27: 878-887. 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0616.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/14/337/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work financially supported by the National Research Lab Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No. 2011–0027928); the Marine and Extreme Genome Research Center Program funded by Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Republic of Korea; and the Next Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ009082) of Rural Development Administration in Republic of Korea. Special thanks to ED Co., Ltd. (SCELDIS, Republic of Korea) for SVF extraction and consultation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JP and SHL contributed to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. JJC and JHL contributed to the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. JP and SHL performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors performed a critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pak, J., Chang, JJ., Lee, J.H. et al. Safety reporting on implantation of autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells with platelet-rich plasma into human articular joints. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14, 337 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-337

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-337