Abstract

Background

A number of recent reports published in the UK have put the quality of care of adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) centre stage. These documents set high standards for health care professionals and commissioning bodies that need to be implemented into routine clinical practice. We therefore have obtained the views of recipients and providers of care in inner city settings as to what they perceive are the barriers to providing integrated care.

Methods

We conducted focus groups and face to face interviews between 2005-8 with 79 participants (patients, carers, specialist medical and nursing outpatient staff and general practitioners (GPs)) working in or attending three hospitals and three primary care trusts (PCT).

Results

Three barriers were identified that stood in the way of seamless integrated care in RA from the perspective of patients, carers, specialists and GPs: (i) early referral (e.g. 'gate keeper's role of GPs); (ii) limitations of ongoing care for established RA (e.g. lack of consultation time in secondary care) and (iii) management of acute flares (e.g. pressure on overbooked clinics).

Conclusion

This timely study of the multi-perspective views of recipients and providers of care was conducted during the time of publications of many important reports in the United Kingdom (UK) that highlighted key components in the provision of high quality care for adults with RA. To achieve seamless care across primary and secondary care requires organisational changes, greater personal and professional collaboration and GP education about RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A number of UK national bodies and groups have reported on the components of quality care for people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Key recent reports have been published by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [1], the National Audit Office [2] and the King's Fund [3]. These built on earlier reports from the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Standards of Care (ARMA) [4] and British Society For Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines [5, 6]. These reports overlap with the new focus on quality care throughout the National Health Service (NHS) [7]. Long-term disorders like RA require similar seamless integrated care across the primary/secondary interface as that established for diabetes for example [8].

We report the key findings from an extensive qualitative review of services for RA provided in an inner city environment serving an ethnically diverse and relatively deprived population. Our principal goal was to assess the perceived barriers that prevent the provision of seamless integrated care across the primary and secondary healthcare sectors. We assessed the varying perspectives of patients, carers, specialists and general practitioners (GPs). Studying such a representative and diverse group of patients, carers and clinicians avoids limitations from concentrating on selected patients and clinical staff linked to national groups.

Methods

Participants

Focus groups and face to face interviews held between 2005-8 involved 79 participants working in or attending three hospitals and three primary care trusts (PCTs). PCTs were part of the NHS and provided some primary and community services or commissioned them from other providers, and were involved in commissioning secondary care. These groups comprised:

a. Two patient focus groups: a purposive sample of 11 RA patients was obtained from one hospital outpatient department; their selection was stratified by disease duration, gender, ethnicity and age. They comprised 8 females and 3 males with a mean age of 58 years and mean disease duration of 12 years; eight were Caucasian and three from black and ethnic groups. One patient refused to take part.

b. Patient interviews: a quota sample of 26 patients was obtained from the same hospital as the focus group participants and one other hospital outpatient department to reflect socio-demographic characteristics and duration of illness of the two RA clinics' population. They comprised 22 females and 4 males of mean age 56 years and mean disease duration ten years; 18 were Caucasian and eight from ethnically diverse groups. There was no overlap in the patients between the individual interviews and focus groups. Nine patients refused to take part.

c. Carers interviews: the carers consisted of a convenience sample of 11 carers from two hospital outpatient departments. They were approached by staff and the researcher through the RA patients they were caring for. They included five females and six males of mean age 61 years; seven were Caucasian and four from other ethnic groups.

d. Specialist Health Care Professionals focus group: six representative members of one multidisciplinary team participated, consisting of consultant rheumatologist, consultant orthopaedic surgeon, rheumatology nurse specialist and allied health professionals (occupational therapist, physiotherapist and podiatrist).

e. Specialist Health Care Professionals interviews: 15 secondary care specialist staff (6 consultants, 4 specialist registrars and 5 rheumatology nurse specialists) from three hospitals. Eight declined participation in the study.

f. Generalist Health Care professional interviews: 13 GPs from three local PCTs.

All patients met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA. Socio-demographic details of patients and carers are summarized in Table 1. Written consent was obtained from each participant and each study was fully approved by the relevant local Research Ethics and Research and Development committees.

Data Generation

The audio taped focus groups and 1:1 interviews were carried out in private rooms using a semi structured interview guide [9]. The interview schedules were based on related literature [10, 11] and the researchers' experiential knowledge. Focus groups and interviews took between one to two hours.

Analysis

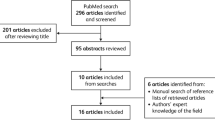

Interview and focus group information was transcribed verbatim. Qualitative computer software NVivo 8 was used to analyse and handle the data. Content and discourse analysis were applied [12, 13], including single counting [14] and deviant results [15]. For validation of the data, external qualitative co-researchers, not involved in the data gathering and analysis, cross-checked initial codes and reached agreement with the researchers about the codes for further data analysis. In addition the data were also presented to two experienced clinicians to assess resonance and plausibility with their clinical experiences. To determine the significance for routine clinical practice in an inner city setting we specifically examined the data from all six qualitative studies for relevance in response to the recent publications.

Results

Through detailed examination of all the data three main barriers to high quality care were identified. These comprised (i) delayed specialist referral; (ii) limitations to routine follow up and (iii) accessing care in times of need (Table 2). Examples of matters raised by patients, carers and healthcare professionals are summarised in Table 3.

Specialist Referral

Patients and Carers

Most patients (29/37) consulted their GPs when their symptoms started. Many (14/37) reported frustration at delays in specialist referral; only one patient commented on being referred early. Some patients (4/37) reported specialist referrals depended on positive blood tests, two of these patients had been diagnosed within the previous twelve months. Delayed referral was mentioned by few carers (2/11).

Healthcare Professionals

All rheumatology specialists in the focus group (3/3) commented on delayed referrals, noting variations in the timing and quality of referrals. This issue did not feature in interviews with individual specialists. Some GPs (4/13) emphasised the need for early referral but many (11/13) commonly waited for 'positive blood tests' for rheumatoid factor before referring. Some GPs (5/13) also waited for confirmatory responses to initial treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids. A number of GPs (5/13) were influenced by their perceived role as 'gate keepers' to specialist care.

Limitations in follow up

Patients and Carers

Many patients (18/37) commented on the importance of monitoring their RA, highlighting the need for physical examinations together with explanations of disease progress and joint discussion of options of new treatments. They wanted the opportunity to participate in decisions about their care. Patients (12/37) focussed on the value of understanding approaches by staff and developing trusting relationship over time with nurses and doctors.

Some patients (8/37) commented critically about insufficient time during consultations with rheumatologists. By contrast there were many positive comments about interactions with rheumatology nurses (32/37). Patients felt more comfortable discussing matters with specialist nurses, who both understood their concerns and had more time (7/37).

Patients reported organisational problems including long waiting times in clinic (13/37), blood sampling for disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) monitoring (9/37), between appointments (5/37) and clinic cancellations and postponements (2/37).

They described mixed experiences with their GPs. On the one hand many (21/37) expressed criticisms about GPs' perceived lack of knowledge of RA and its up-to date treatment (9/37). On the other hand a substantial number of patients reported positive experience in primary care (14/37), often mentioning sympathetic ongoing relationships (8/37). A minority preferred to receive most care in hospital (6/37).

Carers voiced also concerns about waiting times in the clinic (5/11), perceived limited benefits from treatment (4/11) and difficulties with transport to the clinic (3/11). One carer was concerned about GPs limited knowledge. Most (6/11) commented on the importance of good interactions with outpatient clinic staff. Carers noted that RA had major impacts on themselves as well as on the patients they were caring for.

Healthcare Professionals

Specialists' views (16/18) echoed patients' experiences about the paucity of follow up appointments and lack of time during consultations; they found it difficult to adopt a holistic approach with patients. They noted that these pressures had resulted in appointments with rheumatologists being replaced by specialist nurse led clinics.

Most GPs (10/13) commented on their role in providing repeat prescriptions after the initial referral of patients with RA, otherwise they are only marginally involved in ongoing care. Only a minority (4/13) reported they regularly reviewed patients with RA. GPs believed they should combine clinical, administrative and emotional support for RA patients, as part of their comprehensive long-term care.

Few GPs (4/13) commented on the negative impact of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). They stated it influenced their approach to chronic disease management and, as RA falls outside this framework, they thought it reduced the priority given to RA patients in primary care.

Access to Care in Times of Need

Patients and Carers

Patients emphasized the importance of immediate help and support during times of flare of their RA and/or emotional stress (14/37). They tend to approach rheumatology nurses first to gain access to specialists during flare ups. Carers did not comment on this topic.

Healthcare Professionals

Most specialists (11/18) agreed that patients need immediate access during an exacerbation of RA and that the service should respond quickly and effectively. However, such access increased pressure on appointments leading to overbooked clinics and long waiting times.

Most GPs (8/13) considered an important pre-requisite for accessing secondary care was having a personal relationship with the consultant(s) and having knowledge about him or her. These professional links helped access to specialists during acute episodes of RA (9/13). When such links did not exist (4/13) it limited successful primary/secondary care integration. One GP thought this relationship was hindered by the 'choose and book' system as patients might be seen in hospitals unfamiliar to them. (Choose and Book is a national electronic referral service which gives patients a choice of place, date and time for their first outpatient appointment in a hospital or clinic.)

Discussion

This qualitative study identified three key areas in which there were perceived barriers to seamless integrated care in RA from the perspective of patients, carers, specialists and GPs. These are early referral, limitations of ongoing care for established RA and management of acute flares. The study took place during a period in which NICE guidelines and other UK care strategies were being developed [1–7], and therefore helps place our findings in context. Our results are relevant as there are few multi-perspective studies in rheumatology [16] and the multiperspective qualitative approach is very useful to capture the experiences of all stakeholders involved in the treatment and care [17–20].

This qualitative study was conducted in three out-patient clinics and three PCTs consisting of 79 participants of whom 37 were patients. It is difficult to assess how generalisable the findings of this study are, although patients were selected from two different clinics. The question over whether the emerging themes are general ones or merely represent local issues is difficult to answer although evidence from previous studies would suggest that similar issues occur more widely, examples include previous studies which showed delays in referral caused by the presence or absence of positive blood results [21, 22], the need for good access and working relationships with specialists [21, 23] and the lack of experience/knowledge of the primary care physician [23, 24]. The lack of time with rheumatologists and lack of communication between primary and secondary care has also been noted in other parts of the world [23].

Qualitative approaches allow patients to give first-hand accounts of their experiences, in this case their experience of the care provided in primary and secondary settings. By focusing on detailed descriptions and their meaning, such in-depth accounts, from semi-structured interviews, may uncover aspects that cannot be readily captured by structured questionnaires and provide information that is helpful when trying to re-organise services. To our knowledge, no other paper has been published which addresses the views of all stakeholders involved in the care of RA patients.

Delay in referral was highlighted in our study, this has also been suggested in previous guidelines, and observational studies from the UK [2, 3]. Experience with both the Norfolk Arthritis Register [25] and the Steroids in Very Early Arthritis trial [26] have shown that it is possible to see UK patients with inflammatory arthritis in the early stages of their disease. The possible causes of delay in referral are complex and there may be several explanations, such as reflecting organisational aspects; however, alternate explanations may include patient issues such as the disparity between actual observed and perceived time to referral in those patients with long disease duration, who may find it difficult to accurately estimate any delays after such long periods. Patients may also take some time to identify their symptoms and hence achieve referral, which may be reflected in a perceived delay in referral. Finally we do not know if many patients present with features that could be interpreted as leading to rheumatoid arthritis but, over time, melt away and do not progress. Other publications have suggested that people with inflammatory arthritis delay seeking medical advice [2] which could also impact on the time to referral to secondary care. In particular previous studies have shown that ethnicity may play a part in the delay in people seeking help [27] as well as their willingness to accept aggressive treatment [28]; these observations are pertinent given the multicultural population served by South London. However, the issue of people delaying seeking help was not discussed by our patients or GPs. One clear message from our research with GPs was that they are concerned about their role as "gatekeepers" to secondary care. This potentially creates reluctance to refer patients with possible inflammatory arthritis for specialist advice and is a barrier that needs to be removed [2].

Conclusions

There are several limitations in the ongoing management of established RA that could be overcome by changes in the arrangements of the service. One major issue is insufficient time in secondary care appointments so that clinicians do not fully address major concerns for patients. The greater involvement of specialist nurses has been particularly helpful [29], but is not enough by itself. The evidence suggests that specialists should devote more time and resources to the follow up of patients with established RA [10]. The NHS Musculoskeletal Framework [6] should assist this goal by transferring stable musculoskeletal disorders to community based units and allowing specialists to focus on managing RA. This will require a re-evaluation of new to follow-up ratios as low ratios, often considered a mark of effective care, may actually indicate poor quality care in RA.

A second important issue is the limited knowledge many GPs have about RA [3, 23, 24]. This reflects not only the absence of musculoskeletal disorders from the Quality and Outcomes Framework but also the dearth of rheumatology teaching in the postgraduate training of UK GPs [2]. Whilst some GPs provide high quality care, this is by no means universal [3]. It is impractical to equip all GPs with enough expertise to make significant inputs into the management of RA patients, and the best solution may be to make better use of those GPs with particular expertise in the field. This has been utilised in some parts of the country by the establishment of so-called GPSIs (GPs' with a specialist interest). Many of these GPs could be trained within rheumatology departments running clinics alongside consultants gaining greater insight and knowledge, which can then be transferred into the community setting.

The final key issue is the need for close collaboration between primary and secondary care. Terminology may hinder improvements of service as the distinction actually lies between specialist and generalist. As RA is relatively uncommon and GPs have limited knowledge about the disease, we consider its care needs to be managed by specialists. However, there needs to be better links between specialists and the community they serve and good working relationships between GPs and specialists and this might be better served by basing specialist services within the community. Better professional relationships could also be established by inviting community services into specialist centres to meet specialists and to organise teaching sessions. These ties would need to be continually maintained and would require commitment from both sides as it is unlikely that monetary resources would be available through the NHS although other sources could be sought. However, RA patients often need direct access to X-rays and other specialist opinions. Exact solutions would have to be determined at a local level depending on issues such as travel for patients and local community facilities. We realise that this will be a controversial matter that cannot be readily resolved.

References

National Institute of Clinical Excellence: Rheumatoid arthritis. The management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. NICE clinical guideline. 2009, London: NICE, 79

National Audit Office: Services for people with Rheumatoid Arthritis. 2009, London: HMSO, 6191539 07/09 65536

Steward K, Land M: Perceptions of patients and professionals on rheumatoid arthritis. 2009, London: King's Fund

Standards of Care for people with Inflammatory Arthritis. 2004, London: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance

Kennedy T, McCabe C, Struthers G, Sinclair H, Chakravaty K, Bax D, Shipley M, Abernethy R, Palferman T, Hull R, British Society for Rheumatology Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group (SGAWG): BSR guidelines on standards of care for persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005, 44 (4): 553-556. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh554.

Department of Health: Musculoskeletal Services Framework. 2006, London: Department of Health

Darzi A: High Quality of Care for All. 2008, London: Department of Health

Overland J, Mira M, Yue D: Differential shared care for diabetes: does it provide the optimal partition between primary and specialist care?. Diabetic Medicine. 2001, 18 (554): 557-

Britten N: Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995, 311: 251-253.

Lempp H, Scott D, Kingsley G: Patients' views on the quality of health care for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006, 45 (12): 1522-1528. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel132.

Kelly MP, Field D: Medical sociology, chronic illness and the body. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1996, 18 (2): 241-257. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10934993.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005, 15 (9): 1277-1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hodges B, Kuper A, Reeves S: Discourse analysis. BMJ. 2008, 337: a879-10.1136/bmj.a879.

Seale C: The quality of qualitative research. 1999, London: Sage Publications, 119-139. Using numbers

Seale C, Accounting for contradictions: The quality of qualitative research. 1999, London: Sage Publications, 73-86.

Chard J, Dickson J, Tallon D, Dieppe P: A comparison of the views of rheumatologists, general practitioners and patients on the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002, 41: 1208-1210. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1208-a.

Kendall M, Murray SA, Carduff E, Worth A, Harris F, Lloyd A, Cavers D, Grant L, Boyd K, Sheikh A: Use of multiperspective qualitative interviews to understand patients' and carers' beliefs, experiences, and needs. BMJ. 2009, 339: b4122-10.1136/bmj.b4122.

Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, Brown D, Lawton J, Grant E, Murray S, Kendall M, Adam J, Gardee R, Sheikh A: Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ. 2009, 338: b183-10.1136/bmj.b183.

Black J, Lewis T, McIntosh P, Callaly T, Coombs T, Hunter A, Moore L: It's not that bad: the views of consumers and carers about routine outcome measurement in mental health. Aust Health. 2009, 33 (1): 93-9.

Exley C, Field D, Jones L, Stokes T: Palliative care in the community for cancer and end-stage cardiorespiratory disease: the views of patients, lay-carers and health care professionals. Palliat Med. 2005, 19 (1): 76-83. 10.1191/0269216305pm973oa.

Suter LG, Fraenkel L, Holmboe ES: What factors account for referral delays for patients with suspected rheumatoid arthritis?. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 55 (2): 300-5. 10.1002/art.21855.

Robinson PC, Taylor WJ: Time to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis:factors associated with time to treatment initiation and urgent triage assessment of general practitioner referrals. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010, 16 (6): 267-73. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181eeb499.

Bernatsky S, Feldman D, De Civita M, Haggerty J, Tousignant P, Legaré J, Zummer M, Meagher T, Mill C, Roper M, Lee J: Optimal care for rheumatoid arthritis: a focus group study. Clin Rheumatol. 2010, 29 (6): 645-57. 10.1007/s10067-010-1383-9.

Jacobi CE, Boshuizen HC, Rupp I, Dinant HJ, van den Bos GA: Quality of rheumatoid arthritis care: the patient's perspective. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004, 16: 73-81. 10.1093/intqhc/mzh009.

Harrison B, Symmons D: Early inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register with a review of the literature. II. Outcome at three years. Rheumatology (Oxford). 39: 939-949. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.9.939. 200

Verstappen SM, McCoy MJ, Roberts C, Dale NE, Hassell AB, Symmons DP, STIVEA investigators: Beneficial effects of a 3-week course of intramuscular glucocorticoid injections in patients with very early inflammatory polyarthritis: results of the STIVEA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69 (3): 503-9. 10.1136/ard.2009.119149.

Kumar K, Daley E, Khattak F, Buckley CD, Raza K: The influence of ethnicity on the extent of, and reasons underlying, delay in general practitioner consultation in patients with RA. Rheumatology. 2010, 49: 1005-12. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq011.

Constantinescu F, Goucher S, Weinstein A, Fraenkel L: Racial disparities in treatment preferences for rheumatoid arthritis. Med Care. 2009, 47: 350-5. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818af829.

Tijhuis GJ, Zwinderman AH, Hazes JM, Breedveld FC, Vlieland PM: Two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical nurse specialist intervention, inpatient, and day patient team care in rheumatoid arthritis. J Adv Nurs. 2003, 41 (1): 34-43. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02503.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/19/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants for their time and openness during the interviews and focus groups. We are also grateful to Ms Floss Chittenden and Adele Herson's Team for their support with the transcriptions of the interviews and Dr. Simon Carmel and Dr. Karen Lowton for their external help with the data analysis. We are pleased to acknowledge the financial support from Arthritis Research UK and Guy's and St. Thomas Charity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

LP helped to conceive and designed the study, assisted in the data analysis, drafting the manuscript and overseeing the submission process. HG conducted individual interviews with carers and contributed to the data analysis. DS conceived of the study and helped draft the manuscript. GK participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped draft the manuscript. HL helped to conceive and design the study, conducted individual interviews with patients, medical and nurse specialists and GPs and focus groups with patients and specialist multi-disciplinary team members, contributed to the data analysis and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pollard, L.C., Graves, H., Scott, D.L. et al. Perceived barriers to integrated care in rheumatoid arthritis: views of recipients and providers of care in an inner-city setting. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12, 19 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-19