Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of non-coding regulatory RNAs of ~22 nucleotides in length. miRNAs regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally, primarily by associating with the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of their regulatory target mRNAs. Recent work has begun to reveal roles for miRNAs in a wide range of biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Many miRNAs are expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle, and dysregulated miRNA expression has been correlated with muscle-related disorders. We have previously reported that the expression of muscle-specific miR-1 and miR-133 is induced during skeletal muscle differentiation and miR-1 and miR-133 play central regulatory roles in myoblast proliferation and differentiation in vitro.

Methods

In this study, we measured the expression of miRNAs in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice, an animal model for human muscular dystrophy. We also generated transgenic mice to overexpress miR-133a in skeletal muscle.

Results

We examined the expression of miRNAs in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice. We found that the expression of muscle miRNAs, including miR-1a, miR-133a and miR-206, was up-regulated in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice. In order to further investigate the function of miR-133a in skeletal muscle in vivo, we have created several independent transgenic founder lines. Surprisingly, skeletal muscle development and function appear to be unaffected in miR-133a transgenic mice.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that miR-133a is dispensable for the normal development and function of skeletal muscle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of ~ 22 nt non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally [1–3]. The involvement of miRNAs in muscle biology has recently been reported [4–11]. miRNAs regulate the expression of transcription factors and signaling mediators important for cardiac and skeletal muscle development and function [7, 12–14]. Aberrant miRNA expression has been observed in muscle diseases, including cardiac and skeletal muscle hypertrophy, heart failure and muscular dystrophy [13, 15–17].

A subset of miRNAs, miR-1, miR-133, miR-206 and miR-208, are either specifically or highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle and are called myomiRs [6, 7, 13]. Among them, miR-133 was shown to promote the proliferation of myoblasts and inhibits their differentiation in cultured skeletal muscle myoblasts. miR-133 enhances myocyte proliferation, at least in part, by reducing protein levels of SRF, a crucial regulator for muscle differentiation [18, 19]. miR-133 also inhibits the translation of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (nPTB), which controls differential transcript splicing during skeletal-muscle differentiation [20]. Paradoxically, miR-1 and miR-133 exert opposing effects to skeletal-muscle development despite originating from the same miRNA polycistronic transcript. Interestingly, miR-1 and miR-133 also produce opposing effects on apoptosis [21]. Additionally, embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation towards cardiomyocytes is promoted by miR-1 and inhibited by miR-133 [22]. Furthermore, miR-1 and miR-133 are also important regulators of cardiomyocyte differentiation and heart development [22–24].

Primary skeletal-muscle disorders involve different groups of diseases, including muscular dystrophies, inflammatory myopathies and congenital myopathies. Although the number of genes that are involved in muscle disorders increases every year and histological pathology of disease tissue is well documented, the underlying molecular pathways remain poorly understood [25]. Recent studies have begun to link miRNAs to certain muscle-related diseases [6, 13, 15, 26, 27]. In a recent report, comprehensive miRNA expression profiling revealed that a total of 185 miRNAs were dysregulated in samples of diseased muscle tissue from 10 different muscle disorders. Five miRNAs (miR-146b, miR-221, miR-155, miR-214 and miR-222) were consistently regulated in almost all samples that were examined [15], suggesting a possible involvement of common miRNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms in muscle disorders. In addition to those studies of miRNA expression on muscle disorders, a direct genetic link has connected miRNA function to muscular hypertrophy [28]. A mutation that is responsible for the exceptional muscularity of Texel sheep has been mapped to a single G-to-A mutation within the 3' UTR of the mRNA encoding myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) family, which functions to repress muscle growth. This mutation creates a binding site for miR-1 and miR-206, leading to the translational repression of myostatin, which phenocopies the "muscle doubling" that results from the loss of myostatin in mice, cattle, and humans [29, 30]. These findings underscore the importance of miRNA-mediated regulation in diverse muscle biological processes and disease status.

In this study, we attempted to determine the function of miR-133 in skeletal muscle. We employed a gain-of-function approach and generated transgenic mice to overexpress miR-133a-1 in skeletal muscle, using the well-characterized muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter. Surprisingly, we found that miR-133a-1 transgenic mice appear to be normal. Additional analyses indicated that skeletal muscle development and function were not altered in miR-133a-1 transgenic mice. Our study therefore suggests that miR-133a is dispensable for skeletal muscle development.

Methods

Mice

The mdx mice which carry a point mutation in the dystrophin gene were obtained from the Jackson Lab [31]. Skeletal muscle was collected from the hind legs of 1 month old mdx and control mice for RNA extraction. In order to generate miR-133a-1 transgenic mice, a genomic fragment encoding the precursor and franking sequences of the miR-133a-1 gene, which is located on mouse chromosome 18, was amplified by PCR using mouse genomic DNA as a template. The primers used for amplification are: miR-133a-1F: 5' AAGCTAGCGAATTC CATGTGACCCCTCACACACA 3'; miR-133a-1R: 5' TTCTCGAG ACAAGGGGAGCCTGGATCCC 3'. Underlined nucleotide sequences are added adaptors for restriction enzyme digestion. The same primers were used for genotyping of transgenic mice.

The DNA fragment was cloned into a transgenic vector plasmid driving by a muscle-specific muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter [32]. The miR-133a-1 transgenic construct was injected into the pronuclei of C57/Bl6 X C3H hybrid embryos and implanted into pseudo-pregnant recipient females by the University of North Carolina Animal Models Core. Five positive founder lines were obtained.

Ethics Statement

All animal procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under the protocol 08-227.0.

Northern Blot and RT-PCR Analysis

Taqman-based miRNA quantitative RT-PCR (Applied Biosystems) was performed as described [33] using total RNAs isolated from skeletal muscle of 1 month old mdx and the control mice (n = 4). MicroRNA Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously [8, 18]. Briefly, 20 μg of total RNAs isolated from skeletal muscle of 1 month old mdx and the control mice (Figure 1), or from the heart, skeletal muscle and liver tissues of miR-133a-1 transgenic and the control mice (Figure 2), were used and miRNA oligonucleotides with corresponding miRNAs (miR-1a, miR-133a and miR-206) sequences were used as probes. qRT-PCR was repeated three times and Northern blots were performed two times on skeletal muscle of four mice per genotype tested.

Histological and immunohistochemistry analyses

Histological processing and immunohistochemistry staining of skeletal muscle tissues were performed as described previously [8, 34]. Samples were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for routine examination. Laminin conjugated staining was applied to identify sarcolemmal membranes so that myofiber diameter could be directly visualized. Histological and immunohistochemistry analyses were performed on least 4 animals per genotype and repeated independently. All images were acquired by a camera (UFX-DX; Nikon) mounted on an inverted (TE2000, Nikon) or an upright fluorescence microscope (Microphot-SA; Nikon). Digital fluorescent images were captured at room temperature and the images were processed using SPOT (version 3.5.4 for MacOS; Diagnostic Instruments) software and were scaled down and cropped in Photoshop (Adobe) to prepare the final figures. Gel images were quantified using the Photoshop Histogram Analysis and was plotted using Microsoft excel and is shown as relative expression level after normalized by controls.

Results

Changed expression of muscle miRNAs in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice

Mdx mice harbor a spontaneous mutation in the dystrophin gene [31]. The skeletal muscle of the mdx mice is histologically normal early in postnatal development, but starting around 3 weeks muscle necrosis develops with some visible muscle weakness. Therefore, mdx mice have been widely used as an animal model to study the skeletal muscle degeneration/regeneration process [35–37]. We examined miRNA expression in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice. We found that the expression levels of miR-1, miR-133 and miR-206 were higher in the skeletal muscle of one month-old mdx mice (Figure 1A). Northern blot analyses further confirmed a significantly increased expression of miR-206, whereas the expression of miR-1 modestly increased in the muscle muscle of mdx mice (Figure 1B, C). These data indicate that these muscle miRNAs might be involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle degeneration and/or regeneration.

Increased expression of muscle miRNAs in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice. (A) Fold change of the expression of indicated miRNAs in the skeletal muscle of 1 month old mdx mice (n = 3) as detected by qRT-PCR analyses. Statistical differences were determined using the Student's t-test; (*) P < 0.05. (B) Northern blot analyses of the expression of miR-1 and miR-206 in the skeletal muscle of mdx and the wild type control mice (n = 3). Precursors and mature miRNAs are indicated. tRNAs were used as a loading control. (C) The intensity of mature miRNA products from Northern blot was quantified using the Photoshop Histogram Analysis and was plotted using Microsoft excel and is shown as relative expression level after normalized by tRNA. Statistical differences were determined using the Student's t-test; (*) P < 0.05.

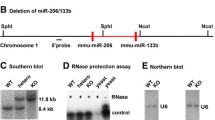

Transgenic overexpression of miR-133a-1 in the skeletal muscle

Recently, miR-133 genes (miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2) were knocked out from the mouse genome. Analysis of mice that lost either miR-133a-1 or miR-133a-2 revealed that both miRNAs are dispensable for development or viability under normal physiological conditions. However, double knockout mice display defects in the heart [24]. In order to further investigate the function of miR-133 in vivo, we took a gain-of-function approach and generated transgenic mice to overexpress miR-133a-1 in skeletal muscle. We used the well-characterized muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter to drive miR-133a-1 expression in skeletal muscle (and to a less extend, cardiac muscle). Genomic DNA from mouse chromosome 18 encoding the miR-133a-1 gene was inserted into an expression vector (Figure 2A). The MCK-miR-133a-1 transgenic construct was injected into fertilized mouse eggs and multiple transgenic founder lines were obtained, as verified by PCR genotyping (Figure 2B). The overexpression of miR-133a-1 in germline-transmitted stable transgenic mice was confirmed by Northern blot analyses. Total RNAs were isolated from indicated tissues, and the overexpression of miR-133a-1 was clearly detected in the skeletal muscle, and to a much less extent, the cardiac muscle, but not in the liver of transgenic mice (Figure 2C, D).

Generation of miR-133a transgenic mice. (A) Diagram of transgenic construct used in this study to overexpress miR-133a in the skeletal muscle of transgenic mice. Two arrows represent PCR primers used for genotyping. MCK: muscle creatine kinase; hGH: human growth hormone. (B) PCR genotyping of miR-133a transgenic founder mice. * indicated genotyping positive founder lines; M: DNA size marker; +: Positive control; -: Negative control. (C) Northern blot analyses of miR-133a expression in the heart, skeletal muscle and liver tissues of the wild type and transgenic mice. tRNAs were used as a loading control. (D) The intensity of skeletal muscle expressed miR-133a from Northern blot was quantified using the Photoshop Histogram Analysis and was plotted using Microsoft excel and is shown as relative expression level after normalized by tRNA. Statistical differences were determined using the Student's t-test; (*) P < 0.05.

Normal skeletal muscle development in miR-133 transgenic mice

All miR-133a-1 transgenic mice were viable and fertile without overt abnormality (Figure 3A, B). The body weight and size between wild type and miR-133a-1 transgenic adult mice (ages from 2 to 12 months) were indistinguishable (n = 40, data not shown). There was not difference in skeletal muscle formation or body fat deposit between miR-133a-1 transgenic mice and their littermate controls (Figure 3C, D). Because the MCK promoter also directed miR-133a-1 overexpression in the heart, albeit at lower level, we determined whether heart development was affected in the transgenic mice. However, our results showed that there was no difference in the gross morphology of the adult hearts of miR-133a-1 transgenic mice and wild type controls (Figure 3E, F).

Normal cardiac and skeletal muscle development in miR-133a transgenic mice. (A-B) The gross morphology of a 6-month old miR-133a transgenic (Tg) mouse is normal and indistinguishable from its wild type (Wt) littermate (n = 4). (C-D) Representative de-skined mice show normal skeletal muscle morphology in miR-133a transgenic mice (Tg) when compared with the wild type littermate (Wt). (E-F) The heart of miR-133a transgenic mouse (Tg) is indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Wt) littermate.

In order to further analyze muscle development, skeletal muscle from the diaphragms of six month old miR-133a-1 transgenic mice was collected and examined by tissue histology (n = 4). As shown in Figure 4, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of diaphragms indicated that the tissue thickness, muscle cell size and numbers were comparable between miR-133a-1 transgenic mice and the control wild type mice. It is noticeable that there is a slight increase in the vesicles in the transgenic diaphragm (Figure 4, arrows).

Histology of skeletal muscle from diaphragm of wild type and miR-133a transgenic mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for skeletal muscle tissue sections of diaphragm from 6 month old wild type (Wt) and miR-133a transgenic mice (MCK-miR-133). Black arrows point to vesicles found in the muscle of transgenic mice.

Similarly, we examined the skeletal muscle of the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) from six month old of both miR-133a-1 transgenic and wild type control mice (n = 4). H&E staining suggested that there was no difference in skeletal muscle morphology between miR-133a-1 transgenic mice and their control littermates (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemistry using an antibody that specifically recognizes laminin, a structural and biologically active component in basement membranes which labels the cell membrane, confirmed that the size and morphology of skeletal muscle in transgenic mice were indistinguishable from that of controls (Figure 5B). Together, these data suggest that miR-133a is dispensable for the normal development and function of skeletal muscle.

Histology of skeletal muscle from wild type and miR-133a transgenic mice. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of skeletal muscle tissue transverse sections of EDL (extensor digitorum longus) muscle from 6 month old wild type (Wt) and miR-133a-1 transgenic mice (MCK-miR-133). (B) Immunohistology of skeletal muscle tissue transverse sections of EDL (extensor digitorum longus) muscle from 6 month old wild type (cont) and miR-133a-1 transgenic mice (MCK-miR-133). Laminin staining outlines muscle cells. DAPI staining illustrates position of nuclei.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the function of miR-133a in skeletal muscle. We found that the expression miR-133a, together with that of miR-206 and miR-1a, was induced in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice. However, transgenic overexpression of miR-133a-1 in skeletal muscle did not result in a noticeable change in skeletal muscle development and morphogenesis. Our results are consistent with a recent report in which miR-133 loss-of-function mice did not induce overt defects in skeletal muscle [24].

It is known that many miRNAs are tissue-specifically expressed. Among them, miR-1, miR-133, miR-206, miR-208 and miR-499 have been described as muscle specific miRNAs, or myomiRs [6, 13]. In addition to their muscle specific expression in normal physiological condition, the expression of some of those myomiRs was shown to be dynamically regulated in pathological and/or diseased muscles. For example, miR-206 levels are elevated in the diaphragm muscle of the mdx mouse, an animal model of muscular dystrophy [27]. Furthermore, miR-1 and miR-206 also participate the regulation of skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation [8]. Both gain- and loss-of-function studies have started to uncover the in vivo function of those muscle miRNAs [10, 23, 34, 38–41]. Interestingly, gene targeting of some of the myomiRs demonstrated that they are dispensable for the normal development and function of cardiac and skeletal muscles [10, 40]. However, many of those miRNAs are indispensable for stress-responsive muscle remodeling. Recently, we reported that overexpression of miR-208a in the heart, which is normally restricted to cardiac tissue, was sufficient to induce cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice [34]. However, in the current study, we did not observe any overt muscle defect in mice expressing the MCK-miR-133a-1 transgene. This may suggest that cardiac and skeletal muscle have adapted distinct requirement for miRNAs for tissue homeostasis.

Given the vast number of miRNAs and the diverse functions in different biological processes observed in the relatively small number of miRNAs studied thus far, it is apparent that many new and unanticipated functions of miRNAs in normal muscle development, function and disorders are waiting to be discovered. Considering that many miRNAs fine-tune gene-expression programs and the intrinsic complexity of miRNA functional models [42, 43], it will important in the future to systematically analyze the potential function of miRNAs in both gain- and loss-of-function animal models.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrate that miR-133a is dispensable for the normal development and function of skeletal muscle.

References

Ambros V: microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell. 2001, 107 (7): 823-826. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00616-X.

Ambros V: The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004, 431 (7006): 350-355. 10.1038/nature02871.

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009, 136 (2): 215-233. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002.

Kim HK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U, Malhotra A, Dutta A: Muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 promotes muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2006, 174 (5): 677-687. 10.1083/jcb.200603008.

Callis TE, Deng Z, Chen JF, Wang DZ: Muscling through the microRNA world. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008, 233 (2): 131-138. 10.3181/0709-MR-237.

Chen JF, Callis TE, Wang DZ: microRNAs and muscle disorders. J Cell Sci. 2009, 122 (Pt 1): 13-20.

van Rooij E, Liu N, Olson EN: MicroRNAs flex their muscles. Trends Genet. 2008, 24 (4): 159-166. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.007.

Chen JF, Tao Y, Li J, Deng Z, Yan Z, Xiao X, Wang DZ: microRNA-1 and microRNA-206 regulate skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation by repressing Pax7. J Cell Biol. 190 (5): 867-879.

Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF: Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103 (23): 8721-8726. 10.1073/pnas.0602831103.

Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, Bassel-Duby R, Sanes JR, Olson EN: MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science. 2009, 326 (5959): 1549-1554. 10.1126/science.1181046.

Rosenberg MI, Georges SA, Asawachaicharn A, Analau E, Tapscott SJ: MyoD inhibits Fstl1 and Utrn expression by inducing transcription of miR-206. J Cell Biol. 2006, 175 (1): 77-85. 10.1083/jcb.200603039.

Callis TE, Wang DZ: Taking microRNAs to heart. Trends in molecular medicine. 2008, 14 (6): 254-260. 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.006.

Williams AH, Liu N, van Rooij E, Olson EN: MicroRNA control of muscle development and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009, 21 (3): 461-469. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.029.

Zhao Y, Srivastava D: A developmental view of microRNA function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007, 32 (4): 189-197. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.006.

Eisenberg I, Eran A, Nishino I, Moggio M, Lamperti C, Amato AA, Lidov HG, Kang PB, North KN, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S: Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression in primary muscular disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007, 104 (43): 17016-17021. 10.1073/pnas.0708115104.

Tatsuguchi M, Seok HY, Callis TE, Thomson JM, Chen JF, Newman M, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Wang DZ: Expression of microRNAs is dynamically regulated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2007, 42 (6): 1137-1141. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.004.

Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL, Borlak J, Haverich A: MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation. 2007, 116 (3): 258-267. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.687947.

Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ: The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006, 38 (2): 228-233. 10.1038/ng1725.

Niu Z, Li A, Zhang SX, Schwartz RJ: Serum response factor micromanaging cardiogenesis. Current opinion in cell biology. 2007, 19 (6): 618-627. 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.013.

Boutz PL, Chawla G, Stoilov P, Black DL: MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes & development. 2007, 21 (1): 71-84. 10.1101/gad.1500707.

Xu C, Lu Y, Pan Z, Chu W, Luo X, Lin H, Xiao J, Shan H, Wang Z, Yang B: The muscle-specific microRNAs miR-1 and miR-133 produce opposing effects on apoptosis by targeting HSP60, HSP70 and caspase-9 in cardiomyocytes. Journal of cell science. 2007, 120 (Pt 17): 3045-3052.

Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, King FW, Yeh RF, Fish JE, Hsiao EC, Schwartz RJ, Conklin BR, Bernstein HS: MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2008, 2 (3): 219-229. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016.

Zhao Y, Ransom JF, Li A, Vedantham V, von M, Muth AN, Tsuchihashi T, McManus MT, Schwartz RJ, Srivastava D: Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007, 129 (2): 303-317. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.030.

Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN: microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 2008, 22 (23): 3242-3254. 10.1101/gad.1738708.

Davies KE, Nowak KJ: Molecular mechanisms of muscular dystrophies: old and new players. Nature reviews. 2006, 7 (10): 762-773. 10.1038/nrm2024.

McCarthy JJ, Esser KA: MicroRNA-1 and microRNA-133a expression are decreased during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007, 102 (1): 306-313.

McCarthy JJ, Esser KA, Andrade FH: MicroRNA-206 is overexpressed in the diaphragm but not the hindlimb muscle of mdx mouse. American journal of physiology. 2007, 293 (1): C451-457. 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2007.

Clop A, Marcq F, Takeda H, Pirottin D, Tordoir X, Bibe B, Bouix J, Caiment F, Elsen JM, Eychenne F: A mutation creating a potential illegitimate microRNA target site in the myostatin gene affects muscularity in sheep. Nature genetics. 2006, 38 (7): 813-818. 10.1038/ng1810.

Tobin JF, Celeste AJ: Myostatin, a negative regulator of muscle mass: implications for muscle degenerative diseases. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2005, 5 (3): 328-332. 10.1016/j.coph.2005.01.011.

Lee SJ: Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2004, 20: 61-86. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836.

Sicinski P, Geng Y, Ryder-Cook AS, Barnard EA, Darlison MG, Barnard PJ: The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science. 1989, 244 (4912): 1578-1580. 10.1126/science.2662404.

Johnson JE, Wold BJ, Hauschka SD: Muscle creatine kinase sequence elements regulating skeletal and cardiac muscle expression in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1989, 9 (8): 3393-3399.

Huang ZP, Chen JF, Regan JN, Maguire CT, Tang RH, Dong XR, Majesky MW, Wang DZ: Loss of microRNAs in neural crest leads to cardiovascular syndromes resembling human congenital heart defects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30 (12): 2575-2586.

Callis TE, Pandya K, Seok HY, Tang RH, Tatsuguchi M, Huang ZP, Chen JF, Deng Z, Gunn B, Shumate J: MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119 (9): 2772-2786. 10.1172/JCI36154.

De la Porte S, Morin S, Koenig J: Characteristics of skeletal muscle in mdx mutant mice. Int Rev Cytol. 1999, 191: 99-148.

Messina S, Mazzeo A, Bitto A, Aguennouz M, Migliorato A, De Pasquale MG, Minutoli L, Altavilla D, Zentilin L, Giacca M: VEGF overexpression via adeno-associated virus gene transfer promotes skeletal muscle regeneration and enhances muscle function in mdx mice. FASEB J. 2007, 21 (13): 3737-3746. 10.1096/fj.07-8459com.

Greco S, De Simone M, Colussi C, Zaccagnini G, Fasanaro P, Pescatori M, Cardani R, Perbellini R, Isaia E, Sale P: Common micro-RNA signature in skeletal muscle damage and regeneration induced by Duchenne muscular dystrophy and acute ischemia. FASEB J. 2009, 23 (10): 3335-3346. 10.1096/fj.08-128579.

Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D: Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005, 436 (7048): 214-220. 10.1038/nature03817.

Olson EN: Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart. Science. 2006, 313 (5795): 1922-1927. 10.1126/science.1132292.

van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill J, Olson EN: Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science. 2007, 316 (5824): 575-579. 10.1126/science.1139089.

van Rooij E, Quiat D, Johnson BA, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Kelm RJ, Olson EN: A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009, 17 (5): 662-673. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013.

Ambros V: The evolution of our thinking about microRNAs. Nat Med. 2008, 14 (10): 1036-1040. 10.1038/nm1008-1036.

Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP: The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008, 455 (7209): 64-71. 10.1038/nature07242.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/12/115/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Wang and Deng laboratories for discussion and support and Dr. John Mably for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the March of Dimes Birth Defect Foundation, National Institutes of Health and Muscular Dystrophy Association. Z Deng is supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation # 30772211. DZ Wang is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ZD and DZW designed the experiment; ZD and JFC performed experiments; ZD and DZ. DZW analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Z., Chen, JF. & Wang, DZ. Transgenic overexpression of miR-133a in skeletal muscle. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12, 115 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-115

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-115