Abstract

Background

The acid-ash hypothesis, the alkaline diet, and related products are marketed to the general public. Websites, lay literature, and direct mail marketing encourage people to measure their urine pH to assess their health status and their risk of osteoporosis.

The objectives of this study were to determine whether 1) low urine pH, or 2) acid excretion in urine [sulfate + chloride + 1.8x phosphate + organic acids] minus [sodium + potassium + 2x calcium + 2x magnesium mEq] in fasting morning urine predict: a) fragility fractures; and b) five-year change of bone mineral density (BMD) in adults.

Methods

Design: Cohort study: the prospective population-based Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Multiple logistic regression was used to examine associations between acid excretion (urine pH and urine acid excretion) in fasting morning with the incidence of fractures (6804 person years). Multiple linear regression was used to examine associations between acid excretion with changes in BMD over 5-years at three sites: lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip (n = 651). Potential confounders controlled included: age, gender, family history of osteoporosis, physical activity, smoking, calcium intake, vitamin D status, estrogen status, medications, renal function, urine creatinine, body mass index, and change of body mass index.

Results

There were no associations between either urine pH or acid excretion and either the incidence of fractures or change of BMD after adjustment for confounders.

Conclusion

Urine pH and urine acid excretion do not predict osteoporosis risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoporosis is a disease that causes pain, disability, reduced quality of life [1], mortality [2], and places substantial demands on health care budgets [3, 4]. According to the acid-ash hypothesis, the modern diet produces residual acid after metabolism [5–7]. This diet-derived acid is thought to be buffered by bicarbonate from bone, followed by bone calcium excretion in the urine [5–7].

Numerous papers in the medical literature (experimental trials [6–14], cross sectional studies [5, 15], prospective studies [16–19], and animal models [20]) identify the potential acid load of the diet as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Well-respected textbooks [21] and reference works [22, 23] uphold this concept. Of public health importance, the acid-ash hypothesis is marketed to the general public as the "alkaline diet", to decrease acidity, to help the body regulate its pH, and to prevent numerous disease processes. Websites[24, 25], lay literature [26–28], magazine advertisements, and direct mail marketing encourage people to measure their urine pH to assess their risk of osteoporosis as well as their general health status [24, 29]. Urine pH of people consuming modern diets tends to be slightly acidic, with pH of approximately 6 [14, 30]. When urine pH is found to be acidic, the "alkaline diet" and the purchase of products to achieve acid-base balance are advocated.

In the medical literature, the diet acid load has been quantified in food ([sulfate + chloride + 1.8x phosphate + organic acids] minus [sodium + potassium + 2x calcium + 2x magnesium] in mEq/day [10]), as well as in urine [10, 11, 31]. The urine acid load has been quantified in two ways: through the measurement of urine pH [10, 11, 31], and from the measurement of net acid excretion [10, 31–33]. Traditionally the urine acid excretion has been estimated from measured titratable acidity, ammonium and bicarbonate [10, 32], which may be inferior measures of acid excretion since ammonium and bicarbonate are volatile and altered by bacterial growth [34] and the measurement of titratable acidity is not a precise method [35]. Urine measures of food intake or the diet acid load take place after absorption has occurred, are not prone to food intake reporting bias, and therefore may provide more accurate estimates.

To our knowledge, the utility of urine pH and/or urine measures of acid excretion to predict osteoporotic outcomes has not been assessed. If urine pH and urine measures of the potential acid load of the diet can predict which individuals are vulnerable to the development of osteoporosis, a novel laboratory testing strategy could be implemented to identify individuals at risk of accelerated bone loss. However, if these measures do not predict which individuals are vulnerable to osteoporosis, the practice of urine pH testing to identify who is at risk for this disease should be discouraged.

The objectives of this study were to determine whether 1) low urine pH, or 2) the calculated acid excretion in urine predict: a) fragility fractures; and b) five-year change of bone mineral density (BMD) in adults.

Methods

This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, University of Calgary and the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS) Design, Analysis and Publication Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants at baseline. CaMOS is a prospective population-based cohort study designed to study skeletal health among a random sample of Canadian adults 25 years of age and above [36].The participants in this study included those recruited from Quebec because they had urine and blood samples obtained at both baseline and at 5-years (Figure 1). At baseline (1996-8) and at five years participants had in-person interviews, measurement of BMD, and collection of samples. Fasting urine samples were collected in the morning after an initial void and a wait of two hours, while participants maintained a fast from the evening before. The urine samples were aliquoted, frozen and stored at -70°C in plastic vials within two hours of collection.

The outcome variables for this study were change of BMD (Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (Hologic 2000)) over 5-years (at the femoral neck (FN), the lumbar spine (L1-4) (LS), and the total hip (HIP)) as well as fragility fractures over seven years of follow-up. Fractures, initially self-reported, were confirmed using radiology reports, over seven years of follow-up. A fragility fracture occurred spontaneously, after a no-fall injury, or from a fall from a standing height or less.

The exposure variables used in this study were: urine pH, and the concentration of the urine ions (mmol/l) summed as estimated acid excretion ([sulfate + chloride + 1.8x phosphate + estimated organic acids [37]] - [potassium + sodium + 2x calcium + 2xmagnesium] mEq/L) [10] based on measurements made on in fasting morning urine. Urine creatinine was included in the adjusted models to control for urine concentration. The urinary excretion of organic acids (including citric, oxalic, malic, succinic, lactic, glutamic, aspartic acid, etc) were estimated from body surface area ([(body surface area × 41)/1.73] [37], where 41 is the median daily organic acid anion excretion (mEq/d) (body surface area was used by these authors as [0.007184x height (cm)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425] [37] based on a recent study that found that anthropometric measures predicted urine organic acids (R2 of 0.15 to 0.39) better than diet measures [37].

Variables considered to be potential confounders included: age, gender, reported family history of osteoporosis among first degree relatives, body mass index (BMI), change in BMI [38–40], hormonal status among the women, presence or absence of kidney disease [41], smoking, medications (thiazide diuretics, bisphosphonates, and estrogen) use, physical activity [42], calcium intake, and vitamin D status. Vitamin D status was assigned as adequate if the serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D was >= 80 nmol/l [43] (Table 1). Medication use was based on prescription bottles viewed at baseline. Women were coded at baseline as estrogen sufficient if they were either premenopausal, or taking estrogen. Urine creatinine was included in the adjusted models to control for urine concentration. Baseline BMD was included in the adjusted models to control for the potential influence of baseline BMD on the change over time [44].

Immediately after thawing, urine pH was measured using a Radiometer PHM82 Standard pH Meter (Copenhagen, Denmark). The calcium, phosphate and creatinine measurements were made using a Vitros 950 (Vitros Chemistry product, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Johnson and Johnson Company, Rochester, NY, USA. Sodium, potassium, magnesium, and chloride were measured using Cobas Integra 700 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, F.Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Urine sulfate was measured using an automated methylthymol blue method.

Regression analysis methods

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used for the fractures analysis and linear regression analysis was used for the BMD analysis. To determine the independent influence of urine pH, models were fully adjusted for potential confounders. Missing values were frequent for smoking status (44.9%), osteoporosis family history (26.8%) and serum 25(OH) vitamin D (49%). Rather than excluding subjects because they had missing values, a third category was added to each of these variables to assess the effect of missingness on outcome. As a result, two indicator variables were created to represent the 3 categories in the regression analyses for each of these variables. Subsequent to performing logistic regression analyses, the predictive accuracies of urine pH and urine acid excretion for fractures was quantified by the c-statistic, having values range from 0.5 (chance accuracy) to 1.0 (perfect accuracy), with the following intermediate benchmarks: 0.6 (fair), 0.7 (good), 0.8 (excellent), and 0.9 (almost perfect). Stata, Version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA), was used for the data analysis.

Results

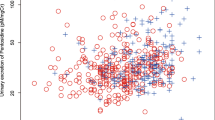

The baseline questionnaire was completed by 1133 subjects (Figure 1); 795 contributed baseline urine samples, 651 (81.9%) had two BMD measurements. The distribution of urine pH is shown in Figure 2. By year seven complete fracture data was recorded for 6804 person years among the 795 subjects. The baseline characteristics and subjects' urine composition in the Fracture and BMD studies were similar (Table 1 & 2).

During follow-up, the mean FN BMD decreased significantly over 5-years by -0.68% (p < 0.001); the HIP BMD did not change significantly (-0.11%) (p = 0.66); and the LS increased significantly (1.92%) (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Eighty-seven (10.9%) cohort subjects had 112 fractures; 46 (5.8%) subjects sustained confirmed fragility fractures. Of those who sustained confirmed fragility fractures, 41 (89%) were aged 50 or greater.

Regression analysis results

There was no association between urine pH or urine acid excretion and the occurrence of fragility fractures (Table 4). Subjects had similar risks of fracture for those with low and high urine pH, whether or not potential confounders were controlled, since the odds ratios were all close to one. The c-statistics illustrated that the unadjusted models for both urine pH and urine acid excretion did not discriminate any better than chance, while the adjusted models had a good ability to predict who would have a fracture (Table 4).

There were two statistically significant associations among the unadjusted relationships between urine measures of acid excretion and change of BMD (Table 5): urine acid excretion with both the change of BMD at the FN and the LS (p = 0.026 and p = 0.041, respectively). Both the slope coefficients and adjusted R2 were close to zero, indicating poor associations. Once adjusted for potential confounding variables, there was no relationship between urine pH or urine acid excretion with the five-year change of BMD for any of the three sites assessed, FN, LS, or HIP (Table 5). Specifically, in the unadjusted models, two relationships were statistically significant: urine acid excretion with both the change of BMD at the FN and the LS (p = 0.026 and p = 0.041, respectively). However, no relationships were statistically significant once confounding was controlled. Once adjusted for confounding, individuals' BMD equally increased and decreased for those with high and low urine pH, and for those with high and low acid excretion. The greatest amount of explained variance (adjusted R2) for the adjusted models for each bone site ranged from two to ten percent. Post estimation residual analysis did not identify any concerns with the assumptions of linear regression.

Discussion

This study revealed no significant associations between either of the urine measures of dietary acid load, urine pH or calculated acid excretion in urine [10], with the occurrence of fragility fractures over 7-years or changes in BMD over 5-years at any of three sites (lumbar spine, femoral neck, or total hip). The adjusted models are more likely to be accurate estimations of the associations between dietary acid load in fasting morning urine samples and bone outcomes than the unadjusted models since the adjusted models control for other risk factors and confounding [45].

The evidence to support the acid-ash hypothesis of osteoporosis predominantly comes from studies using changes in urine calcium as the outcome [6, 8–12, 46], some prospective observational studies [16, 18, 19, 47] and one randomized trial [13]. Although one randomized trial has supported the hypothesis [13], another did not [40]. The randomized trial [13] supporting the hypothesis did not use concealment of allocation, a study quality indicator for randomized studies that is important to avoid bias during the randomization process [48]. Without concealment of allocation, investigators can influence the allocation of individuals into the treatment groups, invalidating the randomization. Trials that do not have concealed allocation can overestimate effectiveness of a therapy [49]. The more recent randomized trial, that concealed allocation, did not reveal any protective effect of either potassium citrate or increased fruit and vegetable consumption on change in BMD [14].

Three previous prospective cohort studies of the hypothesis reported some protective associations between fruit and vegetable, potassium, and/or vitamin C intakes and bone health [16, 18, 19], and thus may support the hypothesis, while two more recent cohort studies do not support it [50, 51]. One of the positive reporting studies did not see a significant protective association for potassium once potential confounders were controlled [16]. Further, it is possible that the associations in agreement with the hypothesis in the cohort studies were due to uncontrolled confounding by estrogen status [19], baseline BMD [16, 19], change of weight status during follow-up [18], and/or vitamin D status [16, 18, 19, 47].

Further, three recent meta-analyses of the acid-ash hypothesis do not support the hypothesis. First, a meta-analysis of calcium balance studies, restricted to studies of superior methodology, revealed no association between net acid excretion and calcium balance, in spite of the strong relationship between net acid excretion and urinary calcium [52]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of protein intake on bone health revealed a small beneficial effect of protein supplementation on lumbar spine BMD in randomized placebo-controlled trials [53]. Further, the acid-ash hypothesis predicts higher phosphate intakes would be associated with increased urinary calcium and lower calcium balance, but this was not supported by a third recent meta-analysis [54].

We used urine samples that had been stored since baseline. Urine pH may change slightly with storage as carbon dioxide (CO2) and ammonia (NH3) evaporate, but the changes are not likely to result in misrepresentation of the measurements. As urine bicarbonate evaporates as CO2 from alkaline urine (H+ and HCO3 - <--> H2O + CO2), pH would increase through the loss of the hydrogen ions [55]. As urine ammonia (NH3) evaporates from more acidic urine, ammonium would converted to ammonia (NH4 + <--> H+ + NH3), hydrogen ions would be liberated and therefore the measured hydrogen ion will increase and thus the pH will decrease. Bicarbonate is found in appreciable amounts only in more alkaline urine, and ammonium in more acidic urine [56]. Therefore these reactions, which cause the alkaline urine to become somewhat more alkaline, and acidic urine to become more acidic, would not likely cause misrepresentation of the measurements of the potential risks.

Our study had four strengths. First, the population from which the cohort was selected has wide ranges of intakes for protein, potassium, fruit and vegetables [57, 58]. Therefore the sample likely had a range of exposures, which improve the chances of revealing the relationship under investigation. Second, the outcome measures used in this study, change in BMD (an accepted clinical measure of the progression of this disease [59]) and occurrence of fragility fractures (a direct measure of osteoporosis [60, 61]) are superior measures of osteoporosis relative to the measurement of urine calcium changes. Third, the use of urine to measure the diet acid load allowed us to avoid the random and systematic errors inherent in food intake measurement. Food-based calculations of acid load excretion are not very precise [31], determining food intake is prone to reporting bias [62, 63], and the absorption of individual ions from food is variable [10, 64]. Food is a complex mixture of numerous compounds, and nutrient absorption depends on the chemical composition as well as "on various interactions with many endogenous and exogenous factors" [35].

This study also had limitations. First, the exposures for this study were measured in fasting morning urine samples, which might be inferior to measures made in 24-hour urine samples. It is possible that urine pH or measures of acid excretion in 24-hour urine samples have a relationship with bone outcomes, and it is also possible that fasting-morning-second-void urines are more reliable measures of diet-acid than 24-hour collections that are more prone to incomplete collection [65]. However, proponents of the acid-ash hypothesis advocate the measurement of pH in morning urine to assess osteoporosis risk [24, 27], so we argue the ability to predict osteoporosis in morning urine samples warranted testing. Second, as a cohort study, the risk of confounding remains, and there is a chance of reporting bias for the potential confounding variables.

Conclusion

This study indicates that two measures of acid excretion from fasting morning urine, low urine pH and the calculated acid excretion in urine, do not identify individuals at risk for osteoporosis, as measured using fragility fractures and changes of bone mineral density. This study cannot determine whether the lack of association between these urine measures of diet acid load and bone outcomes is due to the type of urine sample used, the lack of ability of a single measure to reflect long-term diet acid load, or because the acid-ash hypothesis is not predictive of bone health. Together, this study, the recent critical review [66], and recent meta-analyses [52–54] provide a body of contradicting evidence for the acid-ash hypothesis. Further research is needed to improve our understanding of the role of diet in prevention of osteoporosis and to provide the best possible evidence to support or refute marketing of novel therapies to influence health.

References

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Pickard L: The association between osteoporotic fractures and health-related quality of life as measured by the Health Utilities Index in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos). Osteoporos Int. 2003, 14: 895-904. 10.1007/s00198-003-1483-3.

Robbins JA, Biggs ML, Cauley J: Adjusted mortality after hip fracture: From the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006, 54: 1885-91. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00985.x.

Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB: Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51: 364-70. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51110.x.

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E: Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 271-8. 10.1007/s001980170116.

Macdonald HM, New SA, Fraser WD, Campbell MK, Reid DM: Low dietary potassium intakes and high dietary estimates of net endogenous acid production are associated with low bone mineral density in premenopausal women and increased markers of bone resorption in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81: 923-33.

Maurer M, Riesen W, Muser J, Hulter HN, Krapf R: Neutralization of Western diet inhibits bone resorption independently of K intake and reduces cortisol secretion in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003, 284: F32-F40.

Sebastian A, Harris ST, Ottaway JH, Todd KM, Morris RC: Improved mineral balance and skeletal metabolism in postmenopausal women treated with potassium bicarbonate. N Engl J Med. 1994, 330: 1776-81. 10.1056/NEJM199406233302502.

Lemann J, Pleuss JA, Gray RW, Hoffmann RG: Potassium administration reduces and potassium deprivation increases urinary calcium excretion in healthy adults [corrected]. Kidney Int. 1991, 39: 973-83. 10.1038/ki.1991.123.

Frassetto L, Morris RC, Sebastian A: Long-term persistence of the urine calcium-lowering effect of potassium bicarbonate in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90: 831-4. 10.1210/jc.2004-1350.

Remer T, Manz F: Estimation of the renal net acid excretion by adults consuming diets containing variable amounts of protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994, 59: 1356-61.

Buclin T, Cosma M, Appenzeller M: Diet acids and alkalis influence calcium retention in bone. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 493-9. 10.1007/s001980170095.

Bell JA, Whiting SJ: Effect of fruit on net acid and urinary calcium excretion in an acute feeding trial of women. Nutrition. 2004, 20: 492-3. 10.1016/j.nut.2004.01.015.

Jehle S, Zanetti A, Muser J, Hulter HN, Krapf R: Partial neutralization of the acidogenic Western diet with potassium citrate increases bone mass in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006, 17: 3213-22. 10.1681/ASN.2006030233.

Macdonald HM, Black AJ, Aucott L: Effect of potassium citrate supplementation or increased fruit and vegetable intake on bone metabolism in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 88: 465-74.

Remer T, Manz F: Potential renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995, 95: 791-7. 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00219-7.

Macdonald HM, New SA, Golden MH, Campbell MK, Reid DM: Nutritional associations with bone loss during the menopausal transition: evidence of a beneficial effect of calcium, alcohol, and fruit and vegetable nutrients and of a detrimental effect of fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 79: 155-65.

Tucker KL, Hannan MT, Chen H, Cupples LA, Wilson PW, Kiel DP: Potassium, magnesium, and fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with greater bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999, 69: 727-36.

Tucker KL, Hannan MT, Kiel DP: The acid-base hypothesis: diet and bone in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Eur J Nutr. 2001, 40: 231-7. 10.1007/s394-001-8350-8.

Kaptoge S, Welch A, McTaggart A: Effects of dietary nutrients and food groups on bone loss from the proximal femur in men and women in the 7th and 8th decades of age. Osteoporos Int. 2003, 14: 418-28. 10.1007/s00198-003-1484-2.

Whiting SJ, Draper HH: Effect of a chronic acid load as sulfate or sulfur amino acids on bone metabolism in adult rats. J Nutr. 1981, 111: 1721-6.

DuBose TD: Acid-base disorders. Edited by: Brenner BM. 2000, Brenner & Rector's The Kidney. Saunders, 935-7. 6

Institute of Medicine (IOM): Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. 2004, Washington DC: The National Academies Press

Burns L, Ashwell M, Berry J: UK Food Standards Agency Optimal Nutrition Status Workshop: environmental factors that affect bone health throughout life. Br J Nutr. 2003, 89: 835-40. 10.1079/BJN2003855.

Energize for Life: 2009, (accessed 24 April 2010), [http://www.energiseforlife.com/cat--Alkalising-Supplements--ALKALISING_SUPPLEMENTS.html]

Acid-2-Alkaline: 2010, (accessed 24 April 2010), [http://www.alkalinebodybalance.com/]

Young RO: The pH Miracle: Balance your Diet, reclaim your health. 2003, New York: Grand Central Publishers

Brown SE: Better bones, Better body. 2000, Columbus: McGraw Hill

Vasey C: Acid Alkaline Diet. 2006, Rochester: Healing Arts Press

Acid-2-Alkaline: 2009, (accessed 30 October 2009), [http://www.alkalinebodybalance.com/]

Roughead ZK, Johnson LK, Lykken GI, Hunt JR: Controlled high meat diets do not affect calcium retention or indices of bone status in healthy postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2003, 133: 1020-6.

Michaud DS, Troiano RP, Subar AF: Comparison of estimated renal net acid excretion from dietary intake and body size with urine pH. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003, 103: 1001-7. 10.1016/S0002-8223(03)00469-3.

Lemann J, Litzow JR, Lennon EJ: The effects of chronic acid loads in normal man: further evidence for the participation of bone mineral in the defense against chronic metabolic acidosis. J Clin Invest. 1966, 45: 1608-14. 10.1172/JCI105467.

Lemann J, Gray RW, Pleuss JA: Potassium bicarbonate, but not sodium bicarbonate, reduces urinary calcium excretion and improves calcium balance in healthy men. Kidney Int. 1989, 35: 688-95. 10.1038/ki.1989.40.

Burtis C, Ashwood E, Tietz N: Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry. 1999, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders

Oh MS: New perspectives on acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000, 13: 212-9. 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2000.00061.x.

Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L: Research Notes: Osteoporosis Study (CaMos): Background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging. 1999, 18: 376-87. 10.1017/S0714980800009934.

Berkemeyer S, Remer T: Anthropometrics provide a better estimate of urinary organic acid anion excretion than a dietary mineral intake-based estimate in children, adolescents, and young adults. J Nutr. 2006, 136: 1203-8.

Reid IR: Relationships among body mass, its components, and bone. Bone. 2002, 31: 547-55. 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00864-5.

Reid IR, Plank LD, Evans MC: Fat mass is an important determinant of whole body bone density in premenopausal women but not in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992, 75: 779-82. 10.1210/jc.75.3.779.

Sirola J, Kroger H, Honkanen R: Risk factors associated with peri- and postmenopausal bone loss: does HRT prevent weight loss-related bone loss?. Osteoporos Int. 2003, 14: 27-33. 10.1007/s00198-002-1318-7.

National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002, 39: S1-266. 10.1016/S0272-6386(02)70081-4.

Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, Wu AH: Prostate cancer in relation to diet, physical activity, and body size in blacks, whites, and Asians in the United States and Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 87: 652-61. 10.1093/jnci/87.9.652.

Lappe JM, Davies KM, Travers-Gustafson D, Heaney RP: Vitamin D status in a rural postmenopausal female population. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006, 25: 395-402.

Vickers AJ, Altman DG: Statistics notes: Analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ. 2001, 323: 1123-4. 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1123.

Rothman KJ: Using regression models in epidemiologic analysis. Epidemiology, An Introduction. 2002, New York: Oxford University Press, 181-97.

Fenton TR, Eliasziw M, Lyon AW, Tough SC, Hanley DA: Meta-analysis of the quantity of calcium excretion associated with the net acid excretion of the modern diet under the acid-ash diet hypothesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 88: 1159-66.

Vatanparast H, Baxter-Jones A, Faulkner RA, Bailey DA, Whiting SJ: Positive effects of vegetable and fruit consumption and calcium intake on bone mineral accrual in boys during growth from childhood to adolescence: the University of Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 82: 700-6.

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2008, The Cochrane Collaboration

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG: Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995, 273: 408-12. 10.1001/jama.273.5.408.

Dargent-Molina P, Sabia S, Touvier M: Proteins, Dietary Acid Load, and Calcium and Risk of Post-Menopausal Fractures in the E3N French Women Prospective Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008

Thorpe DL, Knutsen SF, Beeson WL, Rajaram S, Fraser GE: Effects of meat consumption and vegetarian diet on risk of wrist fracture over 25 years in a cohort of peri- and postmenopausal women. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11: 564-72. 10.1017/S1368980007000808.

Fenton TR, Lyon AW, Eliasziw M, Tough SC, Hanley DA: Meta-analysis of the effect of the acid-ash hypothesis of osteoporosis on calcium balance. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2009, Epub

Darling AL, Millward DJ, Torgerson DJ, Hewitt CE, Lanham-New SA: Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90: 1674-92. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27799.

Fenton TR, Lyon AW, Eliasziw M, Tough SC, Hanley DA: Phosphate decreases urine calcium and increases calcium balance: A meta-analysis of the osteoporosis acid-ash diet hypothesis. Nutr J. 2009, 8: 41-10.1186/1475-2891-8-41.

Oster JR, Lopez R, Perez GO, Alpert HA, Al Reshaid KA, Vaamonde CA: The stability of pH, PCO2, and calculated [HCO3] of urine samples collected under oil. Nephron. 1988, 50: 320-4. 10.1159/000185196.

Regulation of hydrogen ion balance: Vander's Renal Physiology. Edited by: Eaton DC. 2004, New York: McGraw Hill, 150-79. 6

Dubois L, Girard M, Bergeron N: The choice of a diet quality indicator to evaluate the nutritional health of populations. Public Health Nutr. 2000, 3: 357-65. 10.1017/S1368980000000409.

Ghadirian P, Shatenstein B, Lambert J: Food habits of French Canadians in Montreal, Quebec. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995, 14: 37-45.

Miller PD, Zapalowski C: Bone mineral density measurements. The Osteoporosis Primer. Edited by: Henderson JE, Goltzman D. 2000, Cambridge: Cambridge Press, 262-76.

Davison KS, Siminoski K, Adachi JD: The effects of antifracture therapies on the components of bone strength: assessment of fracture risk today and in the future. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 36: 10-21. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.04.001.

Davison KS, Siminoski K, Adachi JD: Bone strength: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 36: 22-31. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.04.002.

Rumpler WV, Kramer M, Rhodes DG, Moshfegh AJ, Paul DR: Identifying sources of reporting error using measured food intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008, 62: 544-52. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602742.

Neuhouser ML, Tinker L, Shaw PA: Use of recovery biomarkers to calibrate nutrient consumption self-reports in the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2008, 167: 1247-59. 10.1093/aje/kwn026.

Oh MS: A new method for estimating G-I absorption of alkali. Kidney Int. 1989, 36: 915-7. 10.1038/ki.1989.280.

le Riche M, Zemlin AE, Erasmus RT, Davids MR: An audit of 24-hour creatinine clearance measurements at Tygerberg Hospital and comparison with prediction equations. S Afr Med J. 2007, 97: 968-70.

Bonjour JP: Dietary protein: an essential nutrient for bone health. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005, 24: 526S-36S.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/11/88/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the dedicated Calgary and Quebec City Lab Services staff for their laboratory excellence: Glennis Dioron, Beverly Madden, Shirley Jorge, Kathy Bowe, Brandy Goncalves, and Manjit Dhanjal. We are grateful to Dr. Reinhold Vieth for the vitamin D analyses. We thank Suzette Poliquin, Wei Zhou, Jane Allen, and Marc Gendreau of CaMOS for sharing their understanding of CaMOS and the multiple variables, and Christine Friedenreich for sharing her knowledge about the measurement of physical activity. We thank Sue Ross for discussions about the study methodology. Thank you to Carol and Victoria Fenton for technical assistance. Sources of support: The Canadian Foundation for Dietetic Research (Research funding) as well as doctoral fellowships from the University of Calgary and the Alberta Heritage Fund for Medical Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The author's responsibilities were as follows: All of the authors designed the study, TRF performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript, ME directed the study's statistical analysis, AWL contributed to data analysis and writing of manuscript, SCT, DAH and JPB helped design the study and interpret the findings. We thank Sue Ross for assistance with editing. The funding sources had no influence on the interpretation of results. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fenton, T.R., Eliasziw, M., Tough, S.C. et al. Low urine pH and acid excretion do not predict bone fractures or the loss of bone mineral density: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11, 88 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-88

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-88