Abstract

Background

Careful review of published evidence has led to the postulate that the degree of lumbar lordosis may possibly influence the development and progression of spinal osteoarthritis, just as misalignment does in other joints. Spinal degeneration can ensue from the asymmetrical distribution of loads. The resultant lesions lead to a domino- like breakdown of the normal morphology, degenerative instability and deviation from the correct configuration. The aim of this study is to investigate whether a relationship exists between the sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine, as it is expressed by lordosis, and the presence of radiographic osteoarthritis.

Methods

112 female subjects, aged 40-72 years, were examined in the Outpatients Department of the Orthopedics' Clinic, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete. Lumbar radiographs were examined on two separate occasions, independently, by two of the authors for the presence of osteoarthritis. Lordosis was measured from the top of L1 to the bottom of L5 as well as from the top of L1 to the top of S1. Furthermore, the angle between the bottom of L5 to the top of S1was also measured.

Results and discussion

49 women were diagnosed with radiographic osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine, while 63 women had no evidence of osteoarthritis and served as controls. The two groups were matched for age and body build, as it is expressed by BMI. No statistically significant differences were found in the lordotic angles between the two groups

Conclusions

There is no difference in lordosis between those affected with lumbar spine osteoarthritis and those who are disease free. It appears that osteoarthritis is not associated with the degree of lumbar lordosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spinal osteoarthritis is a common condition, affecting almost 80% of those aged 40 or above [1, 2]. It has also been shown that radiographic osteoarthritis in any site is associated with decreased survival independent of age and other factors like diabetes, smoking, alcohol abuse, history of cardiovascular disease and hypertension [3].

Research so far has identified a number of risk factors that predispose to the occurrence of osteoarthritis. Of note is the impact of joint alignment on the development of degenerative changes. When the shape of a joint is abnormal, the stresses are unequally distributed on its parts [4]. This asymmetrical load distribution contributes to the development of more or less severe, focal or diffuse, degenerative changes [5].

The lumbar spine is a column, which is subjected to the compressive load exerted by the incumbent trunk. Its structure is ideally suited to withstand compressive loads [6, 7]. The sagittal alignment influences the distribution of loads on spinal tissues [8–12]. Several investigators have argued that alterations in spinal balance and curvature are implicated in the development of early osteoarthritis and disc degeneration [11–17] (figure 1).

The development of degenerative changes adversely affects the normal morphology of the affected joints. In the lumbar spine, the changes observed are, amongst others, intervertebral space narrowing [18] especially in the anterior part [19], vertebral body osteophytosis and wedging, [17, 20, 21], loss of anterior column height [22] and hyperplastic modification of the facet joints [23, 24]. Taken as a whole, these lesions lead to a domino- like breakdown of the normal morphology, degenerative instability and deviation from the correct configuration.

These published data indicate that the sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine influences the distribution of loads and accordingly, the development and progression of spinal osteoarthritis. The resultant lesions in turn induce a loss of stability and a progressive deformation of the proper configuration. The aim of the present study is to determine whether an association exists between osteoarthritis presence and the sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine, as it is expressed by lordosis. The hypothesis that is examined is that there is a significant difference between the mean magnitude of lumbar lordosis in patients with and without radiographic evidence of lumbar spine osteoarthritis.

Methods

Participants in an ongoing epidemiological study of the prevalence of vertebral osteoporotic fractures formed the pool from which suitable subjects were selected. These participants are examined at the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete. Part of their comprehensive evaluation is to have anteroposterior and lateral spine X-rays taken in the standing position, using the same procedure and equipment. The main reason for using the same subjects from the aforementioned study was to avoid exposing any further people to radiation. In addition, as those subjects were exclusively women of postmenopausal age, the average age of the subjects was in the period where the frequency of osteoarthritis becomes maximum [1, 2]. Equally important, factors that are known to influence the sagittal curvature of the spine such as age and sex [25–28] would not confound the analysis.

All patients who had secondary osteoarthritis as well as patients whose lumbar curvature might have been altered from disease or iatrogenic intervention had to be excluded. Exclusion criteria were: 1) Congenital spinal diseases 2) Scoliosis 3) Spondylolisthesis - Spondylolysis 4) Vertebral fracture 5) History of spinal surgery 6) Inflammatory arthropathy 7) History of endocrine or metabolic disease.

All lumbar radiographs were examined on two separate occasions, independently, by two of the authors for the presence of features of osteoarthritis. The criteria used where those of Kellgren and Lawrence, and when evidence of two or more criteria were present, the diagnosis of lumbar osteoarthritis was made [29]. Interobserver agreement in detecting or excluding disease presence was 98%. If agreement was not reached, the patient was excluded from the study.

After the application of exclusion criteria, from 524 patients that were examined, only 145 were initially considered as potentially suitable. A further 33 patients were excluded after evaluation of spinal radiographs. The final sample consists of 112 postmenopausal women, aged 42-76 years old (mean 57.3 years).

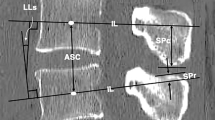

After the designation of the final sample, lumbar lateral radiographs were digitized and measurements were made using the Cobb method with the assistance of a computer program. The use of computers for lumbar lordosis measurements has been shown to be at least equal, if not better, to the manual method [7, 30, 31]. Measurements were made from the top of L1 to the bottom of L5 as well as from the top of L1 to the top of S1. In addition, since several investigators have shown 50% to 75% of the total lordosis between L1 and S1 to be located at the bottom two motion segments [32–38], we also measured the angle between the bottom of L5 to the top of S1.

A priori power analysis showed that in order to have a power of 80% to detect a difference of as little as 10 degrees at the 0.05 level of significance assuming a standard deviation of 15 degrees, 35 women would be needed in each group. The increased enrolment improved the power of the study. Statistical analysis was performed using the one factor ANOVA model with no repeated measurements, chi - square test and for pairwise multiple comparisons, Ìann-Whitney test. All tests are two sided with p < 0.05 considered significant. The analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows, Rel. 13.00. SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL.

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Board of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Crete. Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects prior to their inclusion in the study.

Results

Forty- nine patients were diagnosed with radiographic osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine, while 63 patients had no evidence of the disease and served as controls. No statistically important differences were discovered in age (p= 0.309) and body build (p= 0.731), as it is expressed by body mass index (BMI). This demonstrates the homogeneity of the sample. Similarly, no statistically significant differences were found in lordosis angles between the groups. Additionally, the distribution of values was matched among the groups for all angles. Mean lordosis values for the entire cohort were L1 - L5 39.60 (95% confidence interval 42.05-37.23), L1 - S1 52.70 (95% confidence interval 55.16-50.28), L5 - S1 14.70 (95% confidence interval 15.8-13.56). These results are summarized in table 1 and figure 2 and are comparable with those reported in the literature [1, 25–28]. To sum up, no relationship was found between the degree of lumbar lordosis and either the presence or absence of lumbar spine osteoarthritis.

Discussion

The clinical significance of the sagittal profile of the lumbar spine lies in its association with degeneration and low back pain. As already mentioned in the Introduction, several authors have argued that alterations in spinal balance and curvature are implicated in the development of disc degeneration and spinal osteoarthritis. This study was undertaken to elucidate the relationship, if any, between the sagittal curvature of the lumbar spine and the presence of osteoarthritis in the same area. Our results indicate that no such relationship exists.

When attempting to compare our results with those previously reported in the literature, a problem that comes up is the diversity of methods used to measure lordosis angles radiologically. Even when Cobb's method is used, different authors use different start and end points for measurements [30, 38–41]. Another striking point is that the criteria as to what constitutes lumbar degenerative disease are often not expressly stated. This lack of standardization between reports causes difficulty in making exact comparisons.

The findings of the studies that have examined the correlation of lumbar osteoarthritis and lordosis are contradictory. Lin et al [41] measured lordosis in a sample of 149 symptom-free Chinese adults, 45 of which had some degree of osteoarthritis of their lumbar spine. They report no differences in lordosis between those with and without degenerative changes. Similarly, Lebkowski et al [42] did not find diminished lordosis in patients with lumbar degenerative disk disease. In contrast to these studies, where an association was not discovered, other investigators [38–40] report smaller lordosis and lumbosacral angles in patients with lumbar degenerative disease as compared to controls. Conversely, Farhni and Trueman [43] discovered smaller lordotic angles and lower incidence of degenerative changes in a cadaver sample of Indian men, compared with Caucasians. A number of studies have been conducted where radiographic evidence of lumbar osteoarthritis was present and lordosis was measured, but no attempt was made to investigate any relationship between the two [44–46].

The lack of statistically significant differences in our study can be partly explained by the fact that each person has a unique posture and spinal curvature. What constitutes deviation from the correct alignment and abnormal loading, that could induce degenerative changes on the lower spine, is probably a personalized characteristic. In a similar rationale, lumbar lordosis has a wide range of normal values, and any changes that might occur sooner or later may still be within this normal range. A limitation of the present study is that a cross - sectional rather than a prospective design was applied. Any future research on this subject should also examine the progression of disease of particular patients and the alteration of their individual spinal curves over time.

Conclusions

In conclusion, no differences were found in lordosis between patients affected with lumbar spine osteoarthritis and those who are disease free. It appears that radiographic osteoarthritis is not associated with the degree of lumbar lordosis (figure 3). It is therefore suggested that lumbar lordosis is neither an outcome nor a contributing factor of spinal osteoarthritis.

References

Kramer PA: Prevalence and distribution of spinal osteoarthritis in women. Spine. 2006, 31: 2843-2848. 10.1097/01.brs.0000245854.53001.4e.

O'Neill TW, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, Bhalla AK, Reeve J, Reid DM, Todd C, Woolf AD, Silman AJ: The distribution, determinants, and clinical correlates of vertebral osteophytosis: a population based survey. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 842-848.

Cerhan JR, Wallace RB, el-Khoury GY, Moore TE, Long CR: Decreased survival with increasing prevalence of full-body, radiographically defined osteoarthritis in women. Am J Epidemiol. 1995, 141: 225-234.

Sharma L, Kapoor D, Issa S: Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006, 18: 147-156. 10.1097/01.bor.0000209426.84775.f8.

Gallucci M, Puglielli E, Splendiani A, Pistoia F, Spacca G: Degenerative disorders of the spine. Eur Radiol. 2005, 15: 591-598. 10.1007/s00330-004-2618-4.

Shirazi-Adl A, Parnianpour M: Role of posture in mechanics of the lumbar spine in compression. J Spinal Disord. 1996, 9: 277-286. 10.1097/00002517-199608000-00002.

Rajnics P, Pomero V, Templier A, Lavaste F, Illes T: Computer-assisted assessment of spinal sagittal plane radiographs. J Spinal Disord. 2001, 14: 135-142. 10.1097/00002517-200104000-00008.

Adams MA, Hutton WC: The effect of posture on the role of the apophysial joints in resisting intervertebral compressive forces. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980, 62: 358-62.

Adams MA, Hutton WC: The effect of posture on the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985, 67: 625-629.

Kiefer A, Shirazi-Adl A, Parnianpour M: Synergy of the human spine in neutral postures. Eur Spine J. 1998, 7: 471-479. 10.1007/s005860050110.

Oda I, Cunningham BW, Buckley RA, Goebel MJ, Haggerty CJ, Orbegoso CM, McAfee PC: Does spinal kyphotic deformity influence the biomechanical characteristics of the adjacent motion segments? An in vivo animal model. Spine. 1999, 24: 2139-2146. 10.1097/00007632-199910150-00014.

Umehara S, Zindrick MR, Patwardhan AG, Havey RM, Vrbos LA, Knight GW, Miyano S, Kirincic M, Kaneda K, Lorenz MA: The biomechanical effect of postoperative hypolordosis in instrumented lumbar fusion on instrumented and adjacent spinal segments. Spine. 2000, 25: 1617-1624. 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00004.

Lauerman WC, Platenberg RC, Cain JE, Deeney VF: Age-related disk degeneration: preliminary report of a naturally occurring baboon model. J Spinal Disord. 1992, 5: 170-174. 10.1097/00002517-199206000-00004.

Schlegel JD, Smith JA, Schleusener RL: Lumbar motion segment pathology adjacent to thoracolumbar, lumbar, and lumbosacral fusions. Spine. 1996, 21: 970-981. 10.1097/00007632-199604150-00013.

Kumar MN, Baklanov A, Chopin D: Correlation between sagittal plane changes and adjacent segment degeneration following lumbar spine fusion. Eur Spine J. 2001, 10: 314-319. 10.1007/s005860000239.

Akamaru T, Kawahara N, Tim Yoon S, Minamide A, Su Kim K, Tomita K, Hutton WC: Adjacent segment motion after a simulated lumbar fusion in different sagittal alignments: a biomechanical analysis. Spine. 2003, 28: 1560-1566. 10.1097/00007632-200307150-00016.

Abdel-Hamid Osman A, Bassiouni H, Koutri R, Nijs J, Geusens P, Dequeker J: Aging of the thoracic spine: distinction between wedging in osteoarthritis and fracture in osteoporosis--a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Bone. 1994, 15: 437-442. 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90822-2.

Urban JP, Roberts S: Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003, 5: 120-130. 10.1186/ar629.

Amonoo-Kuofi HS: Morphometric changes in the heights and anteroposterior diameters of the lumbar intervertebral disks with age. J Anat. 1991, 175: 159-168.

Cheng XG, Sun Y, Boonen S, Nicholson PH, Brys P, Dequeker J, Felsenberg D: Measurements of vertebral shape by radiographic morphometry: sex differences and relationships with vertebral level and lumbar lordosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1998, 27: 380-384. 10.1007/s002560050402.

Kasai Y, Kawakita E, Sakakibara T, Akeda K, Uchida A: Direction of the formation of anterior lumbar vertebral osteophytes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009, 10: 4-10.1186/1471-2474-10-4.

Bridwell KH: Causes of sagittal spinal imbalance and assessment of the extent of needed correction. Instr Course Lect. 2006, 55: 567-75.

Benoist M: Natural history of the aging spine. Eur Spine J. 2003, 12: S86-89. 10.1007/s00586-003-0593-0.

Grenier N, Kressel HY, Schiebler ML, Grossman RI, Dalinka MK: Normal and degenerative posterior spinal structures: MR imaging. Radiology. 1987, 165: 517-525.

Milne JS, Lauder IJ: Age effects in kyphosis and lordosis in adults. Ann Hum Biol. 1974, 1: 327-337. 10.1080/03014467400000351.

Fernand R, Fox DE: Evaluation lumbar lordosis. A prospective and retrospective study. Spine. 1985, 10: 799-803. 10.1097/00007632-198511000-00003.

Voutsinas SA, MacEwen GD: Sagittal profiles of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986, 235-42. 210

Amonoo-Kuofi HS: Changes in the lumbosacral angle, sacral inclination and the curvature of the lumbar spine during aging. Acta Anat (Basel). 1992, 145: 373-7. 10.1159/000147392.

Swagerty DL, Hellinger D: Radiographic assessment of osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2001, 64: 279-286.

Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Janik TJ, Holland B: Radiographic analysis of lumbar lordosis: centroid, Cobb, TRALL, and Harrison posterior tangent methods. Spine. 2001, 26: E235-242. 10.1097/00007632-200106010-00003.

Schuler TC, Subach BR, Branch CL, Foley KT, Burkus JK: Segmental lumbar lordosis: manual versus computer-assisted measurement using seven different techniques. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004, 17: 372-379. 10.1097/01.bsd.0000109836.59382.47.

Mitchell T, O'Sullivan PB, Burnett AF, Straker L, Smith A: Regional differences in lumbar spinal posture and the influence of low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008, 9: 152-10.1186/1471-2474-9-152.

Stagnara P, De Mauroy JC, Dran G, Gonon GP, Costanzo G, Dimnet J, Pasquet A: Reciprocal angulation of vertebral bodies in a sagittal plane: approach to references for the evaluation of kyphosis and lordosis. Spine. 1982, 7: 335-342. 10.1097/00007632-198207000-00003.

Korovessis PG, Stamatakis MV, Baikousis AG: Reciprocal angulation of vertebral bodies in the sagittal plane in an asymptomatic Greek population. Spine. 1998, 23: 700-704. 10.1097/00007632-199803150-00010.

Bernhardt M, Bridwell KH: Segmental analysis of the sagittal plane alignment of the normal thoracic and lumbar spines and thoracolumbar junction. Spine. 1989, 14: 717-721. 10.1097/00007632-198907000-00012.

Vedantam R, Lenke LG, Keeney JA, Bridwell KH: Comparison of standing sagittal spinal alignment in asymptomatic adolescents and adults. Spine. 1998, 23: 211-215. 10.1097/00007632-199801150-00012.

Gelb DE, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Blanke K, McEnery KW: An analysis of sagittal spinal alignment in 100 asymptomatic middle and older aged volunteers. Spine. 1995, 20: 1351-1358.

Jackson RP, McManus AC: Radiographic analysis of sagittal plane alignment and balance in standing volunteers and patients with low back pain matched for age, sex, and size. A prospective controlled clinical study. Spine. 1994, 19: 1611-1618. 10.1097/00007632-199407001-00010.

Jackson RP, Peterson MD, McManus AC, Hales C: Compensatory spinopelvic balance over the hip axis and better reliability in measuring lordosis to the pelvic radius on standing lateral radiographs of adult volunteers and patients. Spine. 1998, 23: 1750-1767. 10.1097/00007632-199808150-00008.

Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Holland B: Elliptical modeling of the sagittal lumbar lordosis and segmental rotation angles as a method to discriminate between normal and low back pain subjects. J Spinal Disord. 1998, 11: 430-439. 10.1097/00002517-199810000-00010.

Lin RM, Jou IM, Yu CY: Lumbar lordosis: normal adults. J Formos Med Assoc. 1992, 91: 329-333.

Lebkowski WJ, Lebkowska U, Niedzwiecka M, Dzieciol J: The radiological symptoms of lumbar disc herniation and degenerative changes of the lumbar intervertebral discs. Med Sci Monit. 2004, 10: 112-114.

Fahrni WH, Trueman GE: Comparative radiological study of the spines of a primitive population with North Americans and North Europeans. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965, 47: 552-5.

Tuzun C, Yorulmaz I, Cindas A, Vatan S: Low back pain and posture. Clin Rheumatol. 1999, 18: 308-312. 10.1007/s100670050107.

Inaoka M, Yamazaki Y, Hosono N, Tada K, Yonenobu K: Radiographic analysis of lumbar spine for low-back pain in the general population. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000, 120: 380-385. 10.1007/PL00013766.

Torgerson WR, Dotter WE: Comparative roentgenographic study of the asymptomatic and symptomatic lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976, 58: 850-853.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/11/1/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by the PENED 2003 program under grant 03ED966, co-funded by, the European Union--European Social Fund 75%, the Greek State--Ministry of Development--General Secretariat of Research and Technology 25%, and a private sector. In the framework of Measure 8.3 of the Operational Program "Competitiveness"--3rd Community Support Framework.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the study. MP and GP collected the data. All authors carried out data analysis and participated in the drafting of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Papadakis, M., Papadokostakis, G., Kampanis, N. et al. The association of spinal osteoarthritis with lumbar lordosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11, 1 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-1