Abstract

Background

The 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) is representative of daily-life activities and reflects the functional capacity of patients. The change of oxygen uptake (VO2) in the initial phase of low-intensity exercise (VO2 kinetics) can be used to assess submaximal exercise performance of patients.

The objective of the following study was to analyse VO2 kinetics in patients with different pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases. In addition, we investigated the extent to which VO2 kinetics at the onset of the 6MWT were associated with exercise capacity, morbidity and mortality.

Methods

VO2 kinetics of 204 patients and 16 healthy controls were obtained using mobile telemetric cardiopulmonary monitoring during a 6MWT. A new mean response time (MRT) index (wMRT) was developed to quantify VO2 kinetics by correcting MRT for work rate. The differences in wMRT between disease categories as well as the association between wMRT and patients’ exercise capacity and outcome - time to hospitalization/death- were tested.

Results

The assessment of a robust wMRT was feasible in 86% (244/284) patients. wMRT was increased in patients compared to healthy controls (p <0.001). wMRT was largest in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). There were significant associations between wMRT and exercise capacity in all patients. High wMRT was found to be associated with a high rate of death and re-hospitalization in patients with CHF (p = 0.024). In patients with pulmonary diseases and pulmonary hypertension wMRT was not associated with outcome (p = 0.952).

Conclusions

Submaximal exercise performance of patients is reduced. O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise are associated with exercise capacity in all patients. wMRT was found to be an important prognostic factor in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), but not with pulmonary diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) has been classically performed on a cycle-ergometer or motorised treadmill using a rapid ramped incremental protocol to the limit of tolerance [1]. Since most activities of daily living are performed in a non-incremental fashion and at submaximal level of exertion, the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) may be more representative of daily-life activities and may reflect the functional capacity of patients more accurately [2]. In addition, because most activities of daily living require repetitive submaximal effort, it may be postulated that analysing the cardiopulmonary responses during a transition from rest to submaximal intensity work may provide important information. Therefore, there is a growing interest in submaximal exercise parameters capable of reflecting the functional capacity of patients.

The change of oxygen uptake (VO2) during constant work exercise (VO2 on-kinetics) is classically subdivided into three functionally distinct phases [3, 4]. A rapid first phase characterized by a short time delay of approximately 20 seconds reflects an increase in pulmonary blood flow. After the first phase, O2 uptake gradually increases in an approximately mono-exponential fashion (phase 2) until a steady state level (VO2SS) (phase 3) is attained. Phase 2 reflects the ability of the cardiopulmonary system to deliver oxygen and the amount of oxygen that is utilized by skeletal muscles. At the onset of exercise there is a delay in skeletal muscle mitochondrial ATP production due to a limited oxygen supply (oxygen deficit). Until the steady state is attained, anaerobic glycolysis compensates for this short-term oxygen deficit [5, 6].

VO2 on-kinetics can be characterized by the time (mean response time: MRT) required for VO2 to achieve 63% of the VO2SS in response to physical stress [7, 8]. MRT is usually calculated in a CPET setting using a constant work rate protocol [8, 9]. As the work rate during the 6MWT is mostly determined by the patients’ individual effort, MRT has to be calculated differently. In this study, a new MRT index (wMRT) is proposed to quantify VO2 kinetics at the onset of exercise by correcting MRT for work rate during the first phase of the 6MWT.

It has been demonstrated that patients with chronic pulmonary or cardiac disorders exhibit slower VO2 on-kinetics [10, 11] when compared to healthy age-matched controls.

More knowledge of the physiological determinants of O2 uptake kinetics at the onset of exercise may lead to a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms causing functional impairments in patients. The importance of assessing VO2 kinetics in the initial phase of low-intensity exercise may be underlined by that fact that peak VO2 during a maximal exercise test is influenced by conditions other than the underlying disease, the patient’s motivation and the criteria used to terminate the test [12]. In addition, it has been demonstrated in several chronic diseases that VO2 on-kinetics have a higher prognostic value than peak VO2[13].

No data exist about the clinical utility of this refined method to quantify functional capacity of patients. Therefore, the main purpose of the present study was to analyse VO2 kinetics at the onset of exercise in patients with different pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases using mobile telemetric cardiopulmonary monitoring (MOB). Given the vast pathophysiological heterogeneity of these diseases it may be reasonable to presume that different diseases may have different VO2 kinetics. Secondarily, we investigated the extent to which VO2 kinetics are associated with exercise capacity (VO2SS and 6-Minute Walking Distance, 6MWD). The third aim of the present study was to investigate if VO2 kinetics are associated with morbidity and mortality in these patients.

Methods

Study design

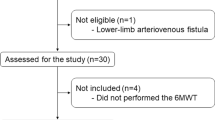

Patients referred to the Pulmonary Division of the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland between August 2003 and June 2007 were considered for participation in the study (Figure 1). Healthy volunteers were recruited from among the hospital staff and college students. Exclusion criteria were as follows: need for oxygen supply or resting transcutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2) of <85% while breathing room air, inability to walk, any acute coronary event during the previous month and conditions precluding the use of a face mask (e.g. anatomic anomaly, claustrophobia or panic disorder). The follow-up was performed by interviewing the referring physician and/or by chart review.

Study exclusions due to technical issues or loss of follow-up. Nine (3%) tests were excluded due to significant patient-related or technical flaws. In thirty-eight (15%) tests it was not possible to fit an acceptable oxygen uptake kinetics curve. Two hundred and twenty tests (82%) were included in the final analysis.

All patients gave informed consent. Our local institutional review board (Ethikkommission beider Basel (EKBB)) approved the study. Parts of the study population data had also been used in another study evaluating the feasibility and safety and clinical usefulness of a MOB-enhanced 6MWT [14].

Six-minute walk test

The 6MWT was performed according to the guidelines published by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) [2] with a standardized encouragement in a 30 m corridor. All tests were conducted by the same experienced technician. Before starting the 6MWT, patients rested seated for three to five minutes until stable VO2 values were recorded (VO2rest). Spirometry was performed prior to the test. The 6MWT was followed by a recovery phase, where the patient rested on a chair. Total walking distance, Borg's dyspnoea score and the subjective limiting factor were recorded.

Six-minute walk test with MOB device

We used the Oxycon Mobile® (Viasys Healthcare, USA) portable, wireless cardiopulmonary exercise testing device to measure breath-by-breath oxygen exchange kinetics. Pulse rate was determined using an ECG-triggered belt (Polar® Electro OY T-61). SpO2 was measured using a finger clip. VO2 and carbon dioxide output (VCO2), tidal volumes and breathing frequency were assessed using a facemask (dead space <70 ml) with a flow sensor and a gas analyser. The patient carried data storage and transfer units by using a dedicated harness. Wireless transfer of breath-by-breath data to a laptop computer allowed real-time monitoring. The additional weight (950 g) of the equipment has no effect on walking distance [14]. The exact 6MWT-MOB procedure has been described in previously published work [14].

ATS criteria for the determination of test intensity were applied [1]: the effort was considered to be maximal if either one or more of the following criteria were fulfilled: (1) maximal heart rate >90% predicted, (2) VO2peak >84% of the predicted maximum, and (3) ventilatory reserve <11 liters or <15%. Ventilatory reserve, VO2max predicted and maximal predicted heart rate were calculated using standard equations [15, 16]. Spirometry was interpreted according to the ATS/ERS guidelines [17].

Curve fitting of oxygen uptake

Original breath-by-breath data were imported from the MOB device. Raw data were pre-processed by averaging the breath-by-breath measurements over consecutive periods of 20 seconds (Figure 2, panel A and B). Curves were modelled using asymptotic regression models describing the oxygen uptake during the 6MWT.

Pre-processing of oxygen uptake during 6MWT and curve fitting. Panel A shows the raw breath-by-breath data. Panel B displays the data after averaging over successive periods of 18 seconds. Panel C depicts the curve fitting (red line) during the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), together with the parameter estimates including the lower limit (y1), the upper limit (y2), and the oxygen deficit (O2def), from which the mean response time is derived.

with y1 the lower limit at t = 0, y2 the upper limit, and the parameter τ >0 determining the steepness of the increase as t elapses. In physiological terms, this translates into:

with VO2rest the oxygen uptake at rest, and VO2ss the oxygen uptake at steady state during exercise.

Notice that the phase I classically characterized by a short time delay was not modelled in the current study. This time delay was undistinguishable from the second exponential phase as often happening in vivo [18]. A gain of stability was obtained by not using an over-parameterized model, which over compensated the potential risk of slight systematic over estimation of τ.

The oxygen deficit (O2def) is defined as the area between an instantaneous increase of oxygen to the maximum upper limit and the observed asymptotic rise of oxygen (Figure 2, panel C) [19]. Since no time delay is taken into account, the mean response time (MRT) corresponds to the time constant (τ) of the exponential function describing the rate of oxygen increase [10]. It represents to the time needed for a 63% increase in oxygen uptake and can also be defined as follows:

Models were fitted on VO2 kinetics using nonlinear regression with the standard Gauss-Newton optimization algorithm and assuming error terms which are normally distributed, mutually independent, centred around 0 and of unknown variance. Each individual curve was analysed graphically and the goodness-of-fit was first assessed visually and with the help of the Neill’s lack-of-fit test [20].

Mean response time reparameterization

In this study, a new MRT index (wMRT) was developed to quantify VO2 kinetics at the onset of exercise by correcting MRT for work rate during the first phase of the 6MWT. The difference between O2 uptake at rest and during effort (VO2ss - VO2rest) was used as a proxy for work rate during the first phase of the 6MWT. MRT was then reparameterized as follows:

MRT reparameterization using other variables such as walking distance (WD) was not possible, probably because of the fact that WD reflects total exercise capacity rather than the initial phase of a submaximal exercise test and is also influenced by muscular or skeletal function as well as motivational level.

Statistical data analysis

Descriptive data for continuous variables are expressed as mean, standard deviation and percentages for frequencies. Variables were tested for parametric distribution by applying the Shapiro-Wilk Test (null hypothesis rejection set at p < 0.25). Univariate linear regression was performed to evaluate possible associations between wMRT and measures reflecting exercise capacity (VO2SS, 6MWD). A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Differences between continuous variables were tested using linear models (ANOVA F-test). Time-to-event data was modelled using Kaplan-Meier estimators, and hypothesis testing was performed using Cox-proportional hazards regression (Wald test). All the analyses were done using the R statistical software [21], including the extension package drc for curve fitting [22] and nlstools for the diagnoses of the quality of fit in nonlinear regression [23].

Results

Fit of oxygen kinetics and patient characteristics

Two hundred and eighty two individuals were examined. Nine patients had to be excluded for reasons of technical failure, insufficient cooperation or incomplete data. Fifteen patients were excluded due to loss of follow-up, lung transplantation and diagnosis of malignancy. The quality of fit was first assessed visually by two independent investigators in order to detect fits showing obvious lack-of-fit. In thirty-eight patients from all categories except controls, curve fitting did not succeed, leading to exclusion from the analysis. Two distinct patterns of response to exercise were noticed in this group: in twenty-two patients, oxygen uptake did not show a plateau and in sixteen patients, VO2 showed a marked variability after reaching a plateau. Variable walking speed and pauses during the 6MWT are the most likely explanations for this observation. The exclusion process is depicted in Figure 1.

The goodness-of-fit of each of the remaining 220 curves was further assessed using Neill’s lack-of-fit test for nonlinear regression. This test showed no evidence of lack-of-fit for all curves but four, where the Neill’s test provided significant results (adjusted p-values <0.05). These four curves were nevertheless kept in the final analysis as their lack-of-fit was not considered major, and was not significantly impacting the estimate of the model parameters.

Two hundred and four patients and sixteen healthy controls were included in the final analysis. Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. One hundred and twenty eight patients (58%) reached criteria for maximal effort according to ATS guidelines [1]. In the current study the mean RER was 0.86 (0.14) suggesting that only a few patients reached an anaerobic threshold. Patients were categorized according to their underlying diseases: thirty nine patients suffered from restrictive lung disease, eighty-four from COPD, fifty-four from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and twenty-seven from congestive heart failure (CHF).

Exercise capacity and oxygen kinetics at exercise onset

Exercise capacity as assessed by both 6MWD and VO2SS of the patients was significantly reduced compared to that of the healthy controls (Table 1; p <0.001). Exercise capacity did not differ between the different patient categories. Figure 3 shows the box plot distributions of wMRT of the patients with restrictive lung disease, COPD, PAH as well as the patients with CHF. The reparameterized wMRT showed significant differences between patients and healthy controls (p <0.001), the latter showing low wMRT values. Patients with PAH had significantly higher wMRT values as compared with patients with COPD (p = 0.010), patients with restrictive lung disease (p <0.001), and patients with CHF (p <0.001).

Mean response time in the various participants’ categories. The figure shows the box plot distributions of wMRT within the following categories: healthy controls (Healthy); restrictive lung disease (Restrictive); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); congestive heart failure (CHF). The reparameterized wMRT showed significant differences between patients and healthy controls (p <0.001), the latter showing low wMRT values. Patients suffering from PAH have higher wMRT values than patients with COPD (p = 0.010), restrictive lung disease (p <0.001) and with CHF (p <0.001).

Association between oxygen kinetics at exercise onset and exercise capacity

The results of univariate regression analysis are demonstrated in Table 2. The reparameterized wMRT showed a significant association with exercise capacity (VO2SS) in all patients (Figure 4A). Figure 4B demonstrates the association between wMRT and VO2SS in the different disease categories. The reparameterized wMRT showed highly significant associations with VO2SS in patients with COPD (p <0.001), restrictive lung disease (p <0.001) and patients with PAH (p <0.001) (Figure 4B). In all patient categories wMRT was significantly associated with 6MWD.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between wMRT and VO 2ss . A Scatterplot showing the relationship between wMRT and VO2SS in healthy controls (green dots) and in patients (blue dots). B Scatterplot showing the relationship between wMRT and VO2SS in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), restrictive lung disease (Restrictive), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and congestive heart failure (CHF). The red dots in the scatter plot show the patients who suffered an event (death or re-hospitalization) during the follow-up period.

Morbidity and mortality

The follow-up was 17 ± 14 months. Seventeen patients (8%) died and 91 (45%) had to be hospitalized during follow-up. Ninety-five patients (47%) reached the combined endpoint of either death or hospitalization. The red dots in Figure 4B show the patients who suffered an event (death or re-hospitalization) during the follow-up period. Figure 5 gives the results of the Kaplan-Meier analysis of the patients with chronic lung disease including pulmonary hypertension and chronic heart failure dichotomized according to the median wMRT (non- cardiac patients: 1.85×10-3, cardiac patients: 1.59×10-3) into “Low wMRT” and “High wMRT”. No statistical difference was found in patients with chronic lung disease including pulmonary hypertension. In patients with chronic heart disease, a low wMRT was associated with a good outcome, i.e. lower rate death and re-hospitalization (p = 0.024). In patients with pulmonary diseases and pulmonary hypertension wMRT was not associated with outcome (p = 0.952).

Reparameterized mean response time and time to death and/or hospitalization during follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier curves depict the time to death and/or hospitalization in non-cardiac (left panel) and cardiac (right panel) patients, as a function of the reparameterized mean response time (wMRT) dichotomized (based on the median wMRT: non- cardiac patients: 1.85V10-3, cardiac patients: 1.59×10-3) into low vs. high wMRT categories.

Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to analyse VO2 kinetics during the 6MWT in a relatively large population of patients with different pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases using mobile telemetric cardiopulmonary monitoring (MOB). A new MRT index (wMRT) was developed to quantify VO2 kinetics by correcting MRT for work rate. The relevance of this new parameterization was further confirmed by the reproducibility of the prior results from Schalcher and colleagues [9]. wMRT was lower in all patients’ categories compared to healthy controls. Patients with PAH had a significant higher wMRT value compared to the other patients. We found significant associations between wMRT and exercise capacity in all patients. Furthermore, wMRT was found to be a significant prognostic factor in patients with CHF, but not in patients with lung diseases and PAH.

6MWT is easy to administer, well tolerated, and more reflective of activities of daily living than incremental maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) performed on a cycle-ergometer. In addition, because some individuals may not tolerate individualized maximal incremental exercise testing, analysing VO2 kinetics during 6MWT may be a useful alternative to CPET.

There has been controversy about the physiologic responses to the 6MWT in patients and described as both maximal [24, 25] and submaximal [26] sustainable exercise. Interestingly, in this study we found that 128 patients (58%) reached criteria for maximal effort according to the ATS guidelines [1]. Detailed information on factors limiting exercise has been presented in previously published work [14]. Furthermore, although exercise capacity was clearly diminished, no difference was found between the exercise capacity of the patients with different pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases. Despite the vast pathophysiological heterogeneity of these diseases we found that end-exercise oxygen uptake during the 6MWT was not different between patients groups. On the other hand, we found that the O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise were clearly different between groups. The results of the present study may, therefore, lead to a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms causing functional impairments in these patients.

The oxygen uptake at the onset of exercise is the product of cardiac output (CO) and the arterial-venous oxygen difference. The relative contribution of Q determinants (i.e., heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV)) to oxygen uptake is essential in reducing the O2 deficit and corresponding metabolic demand during exercise. The increase in cardiac output at the onset of exercise predominantly depends on the increase in SV and due to an increase in heart rate.

The delay in O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise (wMRT) was largest in patients with PAH. A significant difference in wMRT was found between patients with PAH and the rest of the patients. As patients with PAH exhibit impairment in the distensibility and vasodilatory capacity and reduction in the size of the pulmonary vascular bed, the capacity for SV to augment CO is limited [27–30]. In addition, exercise stresses the pulmonary circulation even more causing an abnormal increase in pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) during exercise (exercise-induced pulmonary hypertension) [31–33]. As exercise even further increases PAP during the 6MWT in PAH, this could explain the significant difference in wMRT found between patients with CHF and PAH in the current study.

In patients with pulmonary diseases the delay in O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise was associated with both 6MWD and VO2SS. Although reduction in exercise capacity in patients with COPD is predominantly related to the combination of increased ventilatory requirements (mainly secondary to increased ventilation/perfusion mismatching) and acute derangements in dynamic ventilatory mechanics, the role of diminished stroke volume on exercise capacity may be underlined by the results of the present study. Borghi-Silva and colleagues [10] have recently demonstrated, that VO2 on-kinetics were associated with disease severity in patients with COPD. Hyperinflation may play an important role regarding heart size and heart dysfunction in patients with COPD. Watz and colleagues [11] found that patients with COPD have an impaired left ventricular diastolic filling and an impaired global right ventricular function and that impaired left ventricular diastolic filling was independently associated with a reduced exercise tolerance. These results may eventually aid in the development of therapeutic approaches to improve the exercise capacity in patients with COPD.

The delay in O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise in patients with heart failure was associated with 6MWD too. In patients with heart failure, delayed O2 on-kinetics may primarily be reduced due to systolic and/ or diastolic left ventricular dysfunction [34, 35]. Controversially, other researchers found that impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure [36, 37].

Besides the changes in SV, a reduced arterial-venous oxygen difference may also play a significant role in the oxygen uptake at the onset of exercise. The latter is dependent on systemic blood flow, the amount of oxygen extraction possible from the systemic capillary blood, and the degree of arterial hypoxemia. Studies evaluating the physiological determinants of O2 uptake kinetics showed that abnormal oxidative metabolism at the skeletal muscle level may also contribute to delayed oxygen-uptake kinetics and to the decreased exercise capacity in patients with several chronic diseases [35, 38].

Meyers and colleagues investigated if exercise capacity is predictor of mortality in a total of 6213 healthy subjects and those with cardiovascular disease. In both groups, the peak exercise capacity achieved was a stronger predictor of an increased risk of death than other established risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as hypertension, smoking, and diabetes [39].

In terms of prognosis, our results are in line with the previous findings showing that high MRT values are associated with a bad prognosis in CHF patients [9]. On the other hand, wMRT was not associated with a bad prognosis for patients with lung disease or PAH.

Limiting factors of our study include the fact that MRT could not be calculated in all patients. In about 17% of cases the curve fit failed. Some of these patients were not able to perform the 6MWT with a constant walking speed or without interruptions. This fact may be the reason for the marked variability in VO2 in 16 patients in whom curve fitting failed. Those patients whose VO2 did not reach a plateau probably increased their walking speed during the 6MWT thus also increasing work rate. In addition they may have been exercising above their anaerobic threshold which permits an upward shift in VO2 and an increased demand on central oxygen transport mediated by increased peripheral metabolism. In the current study only 5 of 204 patients (2.2%) reached the level of RER ≥1.10 suggesting that only a few patients reached an anaerobic threshold. In addition, the RER maximal-exercise RER ≥1.10 is commonly used as a criterion to determine whether a “true” VO2max has been attained during maximal-effort exercise testing. It should however be stressed, that the use of RER ≥1.10 as a criterion for a valid or “true” VO2max in patients with pulmonary diseases has been challenged. Peak exercise performance despite low RER is often seen in patients with a pulmonary limitation to exercise [40].

We did not match age and gender between cases and controls because the purpose of the present study was not to demonstrate exercise intolerance in patients. The current study was in essence “observational”. For this purpose, a cross-sectional design was chosen, using only one single transition per participant. It should be stressed that this may have jeopardized the accuracy and precision of our data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, no difference was found between the exercise capacity of the patients with different pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases. The delay in O2 kinetics at the onset of exercise (wMRT) was largest in patients with PAH. Furthermore, we found significant associations between wMRT and exercise capacity in patients with lung diseases, heart failure and PAH. wMRT was found to be a significant prognostic factor in patients with CHF, but not with pulmonary diseases. The results of the present study may lead to a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms causing functional impairments in these patients. We, therefore, recommend assessing wMRT in future studies investigating exercise capacity, morbidity and mortality in patients with pulmonary diseases and heart failure.

References

American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians: ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167: 211-277.

American Thoracic Society Statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Care Med. 2002, 166: 111-117.

Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Lamarra N, Davis J, Wasserman K: Parameters of ventilatory and gas exchange dynamics during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1982, 52: 1506-

Wasserman K, Whipp BJ, Davis JA: Respiratory Physiology of Exercise. International Review of Physiology, Respiratory Physiology III, vol 23. Edited by: Widdecombe JG. 1981, Boston: University Park Press, 149-

Arena R, Humphrey R, Peberdy MA: Measurement of oxygen consumption on-kinetics during exercise: implications for patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2001, 7: 302-310. 10.1054/jcaf.2001.27666.

Whipp BJ, Ward SA: Physiological determinants of pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990, 22: 62-71.

Cross AM, Higginbotham MB: Oxygen deficit during exercise testing in heart failure. Relation to submaximal exercise tolerance. Chest. 1995, 107: 904-908. 10.1378/chest.107.4.904.

Sietsema KE, Ben Dov I, Zhang YY, Sullivan C, Wasserman K: Dynamics of oxygen uptake for submaximal exercise and recovery in patients with chronic heart failure. Chest. 1994, 105: 1693-1700. 10.1378/chest.105.6.1693.

Schalcher C, Rickli H, Brehm M, Weilenmann D, Oechslin E, Kiowski W, Brunner-La Rocca HP: Prolonged oxygen uptake kinetics during low-intensity exercise are related to poor prognosis in patients with mild-to-moderate congestive heart failure. Chest. 2003, 124 (2): 580-586. 10.1378/chest.124.2.580.

Borghi-Silva A, Beltrame T, Reis MS, Sampaio LM, Catai AM, Arena R, Costa D: Relationship between oxygen consumption kinetics and BODE Index in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012, 7: 711-718.

Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Kretschmar G, Kirsten A, Claussen M, Magnussen H: Decreasing cardiac chamber sizes and associated heart dysfunction in COPD: role of hyperinflation. Chest. 2010, 138 (1): 32-38. 10.1378/chest.09-2810.

Janicki JS, Gupta S, Ferris ST, McElroy PA: Long-term reproducibility of respiratory gas exchange measurements during exercise in patients with stable cardiac failure. Chest. 1990, 97: 12-17. 10.1378/chest.97.1.12.

Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI: Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012, 302 (5): 1050-1063. 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2011.

Tueller C, Kern L, Azzola A, Baty F, Condrau S, Wiegand J, Tamm M, Brutsche M: Six-minute walk test enhanced by mobile telemetric cardiopulmonary monitoring. Respiration. 2010, 80 (5): 410-418. 10.1159/000319834.

Fairbarn MS, Blackie SP, McElvaney NG, Wiggs BR, Paré PD, Pardy RL: Prediction of heart rate and oxygen uptake during incremental and maximal exercise in healthy adults. Chest. 1994, 105: 1365-1369. 10.1378/chest.105.5.1365.

Kervio G, Carre F, Ville NS: Reliability and intensity of the six-minute walk test in healthy elderly subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35: 169-174. 10.1097/00005768-200301000-00025.

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J, ATS/ERS Task Force: Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005, 26 (2): 319-338. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805.

Rossiter HB, Ward SA, Doyle VL, Howe FA, Griffiths JR, Whipp BJ: Inferences from pulmonary O2 uptake with respect to intramuscular [phosphocreatine] kinetics during moderate exercise in humans. J Physiol. 1999, 518: 921-932. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0921p.x.

Wasserman K: Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. 1987, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 10-

Neill JW: Testing for lack of fit in nonlinear regression. Ann Statist. 1988, 16: 733-740. 10.1214/aos/1176350831.

R Development Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2009, Vienna, Austria, ISBN 3-900051-07-0

Ritz C, Streibig JC: Bioassay analysis using R. J Stat Softw. 2005, 12 (5): 1-22.

Baty F, Delignette-Muller ML: nlstools 2011: Tools for nonlinear regression diagnostics. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlstools,

Casas A, Vilaro J, Rabinovich R, Mayer A, Barberà JA, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Roca J: Encouraged 6-min walking test indicates maximum sustainable exercise in COPD patients. Chest. 2005, 128: 55-61. 10.1378/chest.128.1.55.

Onorati P, Antonucci R, Valli G, Berton E, De Marco F, Serra P, Palange P: Non-invasive evaluation of gas exchange during a shuttle walking test vs. a 6-min walking test to assess exercise tolerance in COPD patients. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003, 89 (3–4): 331-336.

Troosters T, Vilaro J, Rabinovich R, Casas A, Barbera JA, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Roca J: Physiological responses to the 6-min walk test in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2002, 20: 564-10.1183/09031936.02.02092001.

Holverda S, Gan CT, Marcus JT, Postmus PE, Boonstra A, Vonk-Noordegraaf A: Impaired stroke volume response to exercise in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47: 1732-1733. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.048.

Provencher S, Chemla D, Hervé P, Sitbon O, Humbert M, Simonneau G: Heart rate responses during the 6-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2006, 27 (1): 114-120. 10.1183/09031936.06.00042705.

Laskey WK, Ferrari VA, Palevsky HI, Kussmaul WG: Pulmonary artery hemodynamics in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993, 21: 406-412. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90682-Q.

Nootens M, Wolfkiel CJ, Chomka EV, Rich S: Understanding right and left ventricular systolic function and interactions at rest and with exercise in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1995, 75: 374-377. 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80557-8.

Tolle JJ, Waxman AB, Van Horne TL, Pappagianopoulos PP, Systrom DM: Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008, 118: 2183-2189. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.787101.

Raeside DA, Smith A, Brown A, Patel KR, Madhok R, Cleland J, Peacock AJ: Pulmonary artery pressure measurement during exercise testing in patients with suspected pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2000, 16: 282-287. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b16.x.

Castelain V, Chemla D, Humbert M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G, Lecarpentier Y, Hervé P: Pulmonary artery pressureflow relations after prostacyclin in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165: 338-340. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2106033.

Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR, Sheikh KH, Sullivan MJ: Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function: failure of the Frank-Starling mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991, 17: 1065-1072. 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90832-T.

Matsumoto A, Itoh H, Yokoyama I, Aoyagi T, Sugiura S, Hirata Y, Kato M, Momomura S: Kinetics of oxygen uptake at onset of exercise related to cardiac output, but not to arteriovenous oxygen difference in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999, 83: 1573-1576. 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00154-X.

Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, Kessler K, Pacak K, Becker LC, Kass DA: Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2006, 114: 2138-2147. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632745.

Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM: Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 56: 845-854. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077.

Drexler H, Riede U, Munzel T, Konig H, Funke E, Just H: Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1992, 85: 1751-1759. 10.1161/01.CIR.85.5.1751.

Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE: Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346 (11): 793-801. 10.1056/NEJMoa011858.

Balady GJ, Arena R, Sietsema K, Myers J, Coke L, Fletcher GF, Forman D, Franklin B, Guazzi M, Gulati M, Keteyian SJ, Lavie CJ, Macko R, Mancini D, Milani RV, American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Clinician's guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2010, 122 (2): 191-225. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e52e69.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2466/14/167/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LK: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. SC: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. FB: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. JW: has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. AG: has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. AA: has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. MT: has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. MB: has been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and has given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Lukas Kern, Sophie Condrau contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kern, L., Condrau, S., Baty, F. et al. Oxygen kinetics during 6-minute walk tests in patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med 14, 167 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-167

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-167