Abstract

Background

Guidelines recommend multifactorial intervention programmes to prevent falls in older adults but there are few randomised controlled trials in a real life health care setting. We describe the rationale, intervention, study design, recruitment strategies and baseline characteristics of participants in a randomised controlled trial of a multifactorial falls prevention programme in primary health care.

Methods

Participants are patients from 19 primary care practices in Hutt Valley, New Zealand aged 75 years and over who have fallen in the past year and live independently. Two recruitment strategies were used – waiting room screening and practice mail-out. Intervention participants receive a community based nurse assessment of falls and fracture risk factors, home hazards, referral to appropriate community interventions, and strength and balance exercise programme. Control participants receive usual care and social visits. Outcome measures include number of falls and injuries over 12 months, balance, strength, falls efficacy, activities of daily living, quality of life, and physical activity levels.

Results

312 participants were recruited (69% women). Of those who had fallen, 58% of people screened in the practice waiting rooms and 40% when screened by practice letter were willing to participate. Characteristics of participants recruited using the two methods are similar (p > 0.05). Mean age of all participants was 81 years (SD 5). On average participants have 7 medical conditions, take 5.5 medications (29% on psychotropics) with a median of 2 falls (interquartile range 1, 3) in the previous year.

Conclusion

The two recruitment strategies and the community based intervention delivery were feasible and successful, identifying a high risk group with multiple falls. Recruitment in the waiting room gave higher response rates but was less efficient than practice mail-out. Testing the effectiveness of an evidence based intervention in a 'real life' setting is important.

Trial registration

Australian Clinical Trials Register ID 12605000054617.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Falls are a major cause of morbidity among older adults, with at least 30% of community-dwelling adults over 65 years of age falling each year [1, 2]. The health and economic burden of falls is large, particularly related to falls resulting in serious injuries such as hip fractures [3, 4]. Adults over 75 years are at the highest risk of falling. Primary health care is a key setting to identify older people at risk of falling.

Multifactorial interventions for falls prevention are particularly effective and are recommended for the prevention of community based falls among older people [5]. Interventions aimed at those at highest risk, particularly those who have fallen previously demonstrate the greatest benefit [6]. Those in the oldest age groups also benefit most, particularly from exercise interventions [7]. Successful trials of exercise programmes focussing on muscle strengthening, balance and walking have been delivered at home [8–11], in a retirement village [12] and in the community [13].

The Prevention of Falls in the Elderly Trial (PROFET) found that a structured interdisciplinary assessment for older people presenting to a hospital emergency department in the United Kingdom after a fall reduced subsequent falls and hospitalisations (odds ratios 0.39 and 0.61, respectively) [14]. The intervention involved detailed medical assessment by a geriatrician with appropriate referral, as well as home based occupational therapy review assessing for environmental hazards with education and advice.

Other single factor interventions that have produced reductions in fall rates include withdrawal of psychotropic medication [15], home hazard assessment [16, 17], vitamin D supplementation (meta-analysis) [18] and group-led exercise interventions [12, 13]. However, there is recent evidence that while oral calcium and vitamin D supplementation in healthy post-menopausal women improve hip bone density, they do not reduce risk of hip fracture and they increase risk of kidney stones [19]. There is inconclusive evidence that nutritional or behavioural interventions reduce falls [6, 20]. Expedited surgery for removal of a first cataract significantly reduced falls [21] while removal of a second cataract did not [22]. A very recent trial showed that comprehensive vision assessment and treatment was associated with an increased risk in falls, although these results were not available at commencement of the current trial [23].

Although there is extensive evidence that some interventions in certain settings among particular populations are successful, research about translating this evidence into practice is needed. It is not clear whether interventions such as those used in the PROFET trial would reduce falls in older people identified in primary health care who had not yet had a fall-related injury. Some home exercise programmes for falls prevention have drawn participants from primary health care, but few studies have examined the use of comprehensive assessment and management of falls risk in this setting [6].

Trials large enough to detect a clinically significant effect are recommended. Interventions and outcome measures could be better described and standardised using a recognised taxonomy, which would allow reproduction and pooling of results. These standards and a taxonomy for interventions are being addressed by the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) initiative [24]. Economic evaluations are recommended as part of evaluations of interventions. More trials have been recommended to assess the impact on injuries of evidence-based falls prevention interventions [25]. Therefore, standard definitions of falls and outcome measures and analyses have been proposed to allow pooling of results.

Recruitment of participants from multiple primary health care settings into a lifestyle programme or trial can have practical problems [26]. There are also risks of selection bias and low recruitment rates if recruitment relies on family physicians identifying potential participants [27, 28]. Other primary health care trials have successfully used placement of research nurses in waiting rooms to ensure systematic and consecutive screening of potential participants, and prompt enrolment and measurement of baseline measures to minimise the selection bias, improve rate of recruitment and reduce the burden on the family physician or practice [29]. Therefore, this method was proposed for the Falls Assessment Clinical Trial (FACT) recruitment strategy. However, recruitment was time-consuming using this method, so a second recruitment strategy was added, using a systematic mail-out to all those in the study age group of each practice. The use of patients' registers to recruit participants has been shown to be marginally more efficient and cost-effective than recruitment during primary health care visits in a previous study of frail older adults [30]. The effect on participation rates, participant characteristics and generalisability of each recruitment strategy has been investigated in this paper.

This paper also describes the design, intervention and characteristics of study participants at baseline in the trial. FACT is a unique study in that it is a community based trial that tests the implementation of an evidence-based falls prevention intervention based in primary health care. In particular, the intervention combines falls-related medical assessment, home hazards assessments, bone health assessment, an exercise programme and a referral pathway coordinated by a community based nurse working with several primary health care practices. FACT uses standardised definitions and outcome measures recommended by ProFaNE to allow pooling of results with other trials. The FACT study design will also incorporate an economic evaluation if the intervention is found to be effective in reducing falls.

Methods

Aims

FACT aims to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a primary health care, individually tailored, multifactorial falls prevention intervention in reducing falls and improving the quality of life and functioning among older people at risk of falling.

Design

The study uses an individual randomised controlled trial design with one year of follow-up and a prospective cost-effectiveness evaluation. The cost-effectiveness evaluation takes a health funder and societal perspective. The Wellington Ethics Committee approved the study in September 2004 (ID number: 04/08/064).

Study population

Adults aged 75 years and older (over 55 years for Maori and Pacific people) who had fallen in the last 12 months were identified within primary health care by two methods: waiting room recruitment in the first seven practices and postal invitations using the practice registers in all practices except the initial practice. Exclusion criteria include being unable to comprehend study information and consent processes, unstable or progressive medical condition, severe physical disability, or dementia (less than 7 on the Abbreviated Mental Test Score) [31].

Recruitment

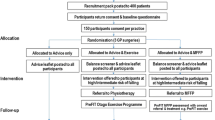

Rolling recruitment of participants from 19 practices in the Hutt Valley region in New Zealand was undertaken from March 2005 to January 2006 (Figure 1). Adults in the eligible age group were screened using a simple question asking if they had a fall or trip in the last 12 months on a form which also described the study briefly, handed to them by the receptionist as they entered the primary health care practice, or by mail-out to all those in the age group from each practice's patient register. If those who had fallen were interested in knowing more about the study from a research nurse, they provided their name and contact phone number and handed the form back to the receptionist or sent the form to researchers by post-paid envelope. The research nurse contacted those interested to provide more information about the study, confirm eligibility (e.g. that a fall meeting the study definition had occurred), and arrange a home visit if appropriate to conduct informed consent and baseline assessment.

Randomisation and blinding

An independent researcher at a distant site carried out computer randomisation of participants, emailing allocation of randomisation of each individual after baseline assessment. The research nurses who undertake outcome measures at each time point remain blind to allocation to minimise measurement bias, although blinding is difficult where the participant is aware of which group they are in and home alterations may be evident at follow-up in the homes of some intervention participants.

Outcome measures

Falls are defined as "an unexpected event in which the participants come to rest on the ground, floor, or other lower level" [25] and are the primary outcome measure. Falls are recorded by participants using postcard calendars, completed daily and posted monthly to the research team. If a fall is indicated on the calendar, a follow-up telephone interview establishes the circumstances and consequences of the fall from the participant, including injury and hospital admission. In a few cases, reports were confirmed from hospital records. Injuries are classified as serious (resulting in a fracture, hospital admission or sutures) or moderate (resulting in bruising, sprains, cuts, abrasions, seeking medical attention or a decrease in physical function for a period greater than or equal to three days) [7].

Secondary outcomes measured at baseline and 12 months are collected by the research nurse and include self-efficacy (modified fear of falling scale [32]), quality of life (SF-36 [33–36]), muscle strength and balance (timed up and go test, 30-second chair stand test [37], FICSIT 4-test balance scale [38] and 7.5 cm block step test [39]), activities of daily living (Nottingham extended activities of daily living profile [40, 41]) and level of physical activity (Auckland Heart Study (AHS) physical activity questionnaire [42]). The timed up and go test measures the time taken to stand from a chair, walk three metres and return to the chair. The 30-second chair stand test measures the number of times the participant is able to stand and return to a seated position in a chair in 30 seconds [37]. The step test measures the number of times the person is able to step one foot fully onto and then off a 7.5 cm block in 15 seconds, repeated for each leg [39]. The average of the two legs is taken for each individual. The FICSIT (Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques) 4-test balance scale requires the participant to adopt four standing balance poses [38].

Other demographic and health variables were collected. Number of medical conditions was collected by self-report from a list of 27 common medical conditions including conditions such as arthritis, depression, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease and stroke.

Cost variables

Unit costs and resource use of the components of the intervention, and costs associated with each fall to the participant and to the health funder, are being recorded over the 12-month duration of the study. If the intervention is found to be effective, then cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated for incremental cost per fall averted [43].

Intervention group

The intervention incorporates aspects from the successful PROFET trial [14], Tinetti's multifactorial intervention trial [44], and the individually tailored Otago Exercise Programme (Table 1) [45]. Intervention participants receive a falls risk assessment by a community based 'Falls and Fracture' nurse coordinator in their own home usually within one month of enrolment. The 'Falls and Fracture' nurse coordinator has gerontological expertise, and was trained in falls prevention. In brief, the intervention includes the following:

• Health assessment: history of circumstances of the fall, medications, previous cardiovascular or neurological illness, continence, vision, postural blood pressure, balance and gait [37, 38], cardiovascular screen (syncope, arrhythmia).

• Home hazards assessment: an audit for environmental safety [14, 17].

• Bone health assessment: a brief osteoporosis risk screen, recommendation for vitamin D and calcium supplementation [46]. DEXA scan and bisphosphonates where indicated [47].

• The Otago Exercise Programme[45].

The nurse provides appropriate advice, education and coordinated medical referral to the family physician, geriatrician, optometrist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist or other professional if indicated, according to the assessment algorithm. Where indicated, the family physician undertakes a more comprehensive medical assessment, medication review and further referral or intervention where appropriate. A month-long pilot of the intervention involving 10 participants from one practice had established the feasibility and operational logistics of the falls and fracture nurse assessment and referral systems prior to the main trial.

The nurse coordinator organises the delivery of the Otago Exercise Programme by a trained health practitioner or physiotherapist for one year. The exercise programme involves home visits at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and after six months to administer the individually tailored strength and balance retraining programme. If the nurse considers the participant would not be able to undertake, or receive benefit from this exercise programme (e.g. timed up and go score of greater than 30 or marked neurological impairment) then she can refer the participant to a community physiotherapist who tailors an alternative exercise programme more appropriate for the participant.

Control group

In addition to usual care, participants in the control group are offered at least two social visits from an accredited visitor such as a nursing student, within one month of enrolment, to control for the effect of social contact by the falls and fracture nurse coordinator and exercise initiator in the intervention group. Control participants also receive a pamphlet produced by the New Zealand Accident Compensation Corporation about prevention of falls in older adults.

Sample size

On the basis of previous falls rates and attrition rates during a similar falls prevention programme we predicted the proportion of the control group and intervention group who will fall during a one year period to be 52% and 32% respectively [14]. To detect this as statistically significant (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.80), 105 participants were required in each group. If an attrition rate of 30% over the 12 months were assumed then a sample of 300 would be required (150 in each of the control and intervention groups).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented and intervention and control groups checked for balance in demographic, health and outcome measures. Recruitment rates and characteristics of participants recruited from the two recruitment strategies are compared.

For the main outcome results at the completion of the study, an intention to treat analysis will be undertaken. The rate of falls for individuals in the two groups will be compared using negative binomial regression models in STATA 9.1. Linear and logistic regression will be used to compare changes in the intermediate measures from baseline to 12 months. Differences in these outcomes between the intervention and control groups will be tested using the regression models, adjusting for baseline values.

Results

Recruitment rates

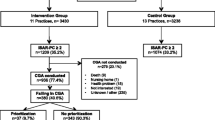

A total of 312 participants were recruited using two methods of recruitment from 19 primary health care practices. As a proportion of those screened, the recruitment rate for the waiting room method (12.3% (90 of 729)) was higher than for the postal method (8.2% (222 of 2705)) (p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the recruitment of participants into the trial using the two methods. Screening in the practice waiting room revealed that 29% (214 of 729) of those screened had had a fall in the previous 12 months. Of those who had fallen, 58% (n = 124) agreed to participate, of whom 73% (n = 90) were eligible. Using the postal method of recruitment, if a fall rate of 30% is assumed (811 of 2705), then 40% agreed to participate (322 of 811). To test this assumption, if fall rates of 20% or 40% were assumed, then 59% (322 of 541) or 30% (322 of 1082), respectively, agreed to participate. Of those who agreed to participate 69% fulfilled eligibility criteria (n = 222).

Characteristics of participants using different recruitment strategies

There was no statistically significant difference in participant demographic, clinical or functional measures between the two different recruitment strategies. There was a non-significant trend for those recruited by the mail-out compared with waiting room recruitment to be slightly younger (mean of 80.6 and 81.2 years, respectively (p = 0.4)), lower weight (body mass index 27 and 28 (p = 0.3)), with fewer medical conditions (6.9 and 7.5 (p = 0.1)) and fewer medications (5.4 and 5.8 (p = 0.3)), slightly better function on tests of strength and balance (timed up and go 14.5 and 16.6 seconds (p = 0.1); step test 8.5 and 7.5 steps (p = 0.07)) and a slightly higher proportion of women (71% and 63% (p = 0.1)). In addition, there was also a trend towards greater numbers of falls in the past 12 months compared with the waiting room recruitment group (3.4 and 2.7 (p = 0.2)).

Baseline characteristics

In the total study sample, 31% (97 of 312) were men. Most participants (n = 303) were between 75 and 98 years of age. However, nine Maori or Pacific participants were between the ages of 60 and 75 years of age because of the different age eligibility criteria for these groups. In total, 276 (88%) participants identified as New Zealand European, 6 (2%) as Maori, 3 (1%) Pacific, one Indian, one Chinese and 29 (9%) identified as other European or other ethnicity. All participants had fallen in the last 12 months, eight (2.5%) had had a previous hip fracture, and 107 (34%) had had any previous fracture in the past. The total study population took an average of 5.5 medications with 29% taking psychotropic medications. Functional measures showed a limited level of function with an average timed up and go score of 15 seconds. The demographic and clinical characteristics by intervention and control groups were balanced at baseline (see Table 2).

Discussion

This paper describes the intervention, design, recruitment strategies and baseline results of the FACT falls prevention trial for older people with a history of falls from a range of primary health care practices. The intervention was multifactorial and the components were evidence-based. Baseline characteristics of intervention and control groups were balanced.

Tests of strength and balance confirmed that this population of older people screened in primary health care with a recent previous fall had relatively low physical function and generally high rates of morbidity and medications. For example, the mean timed up and go of this population was 15.1 seconds (median 12 seconds, interquartile range 10–16 seconds) compared with a mean of 8.5 seconds amongst healthy older people (mean age 75 years) measured by Podsiadlo and Richardson [48], and 9.1 seconds in a cohort of healthy older women (70 years and over) [39]. The mean step test of the FACT study population was 8.2 steps in 15 seconds compared with 17 steps in a study of healthy older people (mean age 73 years) that used the same step dimensions [32], and 16 steps among a healthy cohort of older women [39]. It is likely, therefore, that a strength and balance programme may benefit this population.

It has been shown that opportunistic recruitment, such as by newspaper advertisements, produce less diverse and representative patient populations than recruitment within the appropriate clinical context [49]. However, even if recruitment is undertaken within primary health care, relying on family physicians or practice staff to recruit participants can be problematic due to the time constraints of the staff, and can often produce low recruitment rates and selection bias [27, 28]. Therefore, systematic screening and recruitment from primary health care waiting rooms and by mail-out screening from patient registers were undertaken in this study.

This study showed that systematic screening for previous falls and recruitment within the practice waiting room had higher rates of recruitment than mail-out screening from practice registers. Those identified from the practice waiting room were open to receiving the home based falls prevention programme, with 58% willing to participate compared with 40% using the mail-out strategy, although the latter figure may be imprecise as it assumed a fall rate of 30% in those in the study age group. When the characteristics of participants of the two recruitment strategies were compared there were no significant differences on general characteristics or outcome measures. Therefore, although the recruitment rate was lower using the mail-out method, the method was more time efficient than the consecutive screening and recruitment in the waiting rooms. Either method would be appropriate in future trials. The choice of method may depend on the prevalence of the condition.

Conclusion

Although many of the intervention components have been found to be effective at reducing falls in older people, few studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a new health service combining falls-related medical assessment, home hazards assessment, bone health, exercise intervention and community based nurse coordination of referral and follow-up in a "real world" primary health care context. The multifactorial intervention approach is also testing for the interaction of interventions previously shown to be effective as single interventions in selected populations. Although this has been done previously (PROFET) [14], it has not been well investigated where implementation of a significant proportion of the interventions requires referral outside the research team, with limited control on uptake.

References

Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF, Jackson SL, Brown JS, Fitzgerald JL: Circumstances and consequences of falls experienced by a community population 70 years and over during a prospective study. Age Ageing. 1990, 19 (2): 136-141. 10.1093/ageing/19.2.136.

Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR: The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002, 18 (2): 141-158. 10.1016/S0749-0690(02)00002-2.

Fielden J, Purdie G, Horne G, Devane P: Hip fracture incidence in New Zealand, revisited. N Z Med J. 2001, 114 (1129): 154-156.

Rizzo JA, Friedkin R, Williams CS, Nabors J, Acampora D, Tinetti ME: Health care utilization and costs in a Medicare population by fall status. Med Care. 1998, 36 (8): 1174-1188. 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00006.

Tinetti ME: Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348 (1): 42-49. 10.1056/NEJMcp020719.

Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH, McClure R, Turner C, Peel N, Spinks A: Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, CD000340-4

Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N: Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: a meta-analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002, 50 (5): 905-911. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50218.x.

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Tilyard MW, Buchner DM: Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ. 1997, 315 (7115): 1065-1069.

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM: Falls prevention over 2 years: a randomized controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing. 1999, 28 (6): 513-518. 10.1093/ageing/28.6.513.

Robertson MC, Devlin N, Gardner MM, Campbell AJ: Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 1: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001, 322 (7288): 697-701. 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.697.

Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Devlin N, McGee R, Campbell AJ: Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 2: Controlled trial in multiple centres. BMJ. 2001, 322 (7288): 701-704. 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.701.

Lord SR, Castell S, Corcoran J, Dayhew J, Matters B, Shan A, Williams P: The effect of group exercise on physical functioning and falls in frail older people living in retirement villages: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51 (12): 1685-1692. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51551.x.

Barnett A, Smith B, Lord SR, Williams M, Baumand A: Community-based group exercise improves balance and reduces falls in at-risk older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2003, 32 (4): 407-414. 10.1093/ageing/32.4.407.

Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C: Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999, 353 (9147): 93-97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4.

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM: Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47 (7): 850-853.

Nikolaus T, Bach M: Preventing falls in community-dwelling frail older people using a home intervention team (HIT): results from the randomized Falls-HIT trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51 (3): 300-305. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51102.x.

Cumming RG, Thomas M, Szonyi G, Salkeld G, O'Neill E, Westbury C, Frampton G: Home visits by an occupational therapist for assessment and modification of environmental hazards: a randomized trial of falls prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47 (12): 1397-1402.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Willett WC, Staehelin HB, Bazemore MG, Zee RY, Wong JB: Effect of Vitamin D on falls: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004, 291 (16): 1999-2006. 10.1001/jama.291.16.1999.

Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, Wallace RB, Robbins J, Lewis CE, Bassford T, Beresford SAA, Black HR, Blanchette P, Bonds DE, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Cauley JA, Chlebowski RT, Cummings SR, Granek I, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller LH, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Limacher MC, Ludlam S, Manson JAE, Margolis KL, McGowan J, Ockene JK, O'Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Whitlock E, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Barad D, Women's Health Initiative Investigators: Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354 (7): 669-683. 10.1056/NEJMoa055218.

Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, Bennett DA, Moseley A, Cameron ID, Fitness Collaborative Group: A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the Frailty Interventions Trial in Elderly Subjects (FITNESS). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51 (3): 291-299. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51101.x.

Harwood RH, Foss AJE, Osborn F, Gregson RM, Zaman A, Masud T: Falls and health status in elderly women following first eye cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005, 89 (1): 53-59. 10.1136/bjo.2004.049478.

Foss AJE, Harwood RH, Osborn F, Gregson RM, Zaman A, Masud T: Falls and health status in elderly women following second eye cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2006, 35 (1): 66-71. 10.1093/ageing/afj005.

Cumming RG, Ivers R, Clemson L, Cullen J, Hayes MF, Tanzer M, Mitchell P: Improving vision to prevent falls in frail older people: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007, 55 (2): 175-181. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01046.x.

Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, Todd C, Becker C, PROFANE-Group: Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006, 35 (1): 5-10. 10.1093/ageing/afi218.

Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C, Prevention of Falls Network Europe and Outcomes Consensus Group: Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005, 53 (9): 1618-1622. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x.

Ory MG, Lipman PD, Karlen PL, Gerety MB, Stevens VJ, Singh MAF, Buchner DM, Schechtman KB, Ficsit Group. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques: Recruitment of older participants in frailty/injury prevention studies. Prevention Science. 2002, 3 (1): 1-22. 10.1023/A:1014610325059.

Yallop JJ, McAvoy BR, Croucher JL, Tonkin A, Piterman L, CHAT Study Group: Primary health care research--essential but disadvantaged. Med J Aust. 2006, 185 (2): 118-120.

van der Windt DA, Koes BW, van Aarst M, Heemskerk MA, Bouter LM: Practical aspects of conducting a pragmatic randomised trial in primary care: patient recruitment and outcome assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2000, 50 (454): 371-374.

Elley CR, Kerse NM, Arroll B, Robinson E: Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003, 326: 793-796. 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.793.

Gill TM, McGloin JM, Gahbauer EA, Shepard DM, Bianco LM: Two recruitment strategies for a clinical trial of physically frail community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001, 49 (8): 1039-1045. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49206.x.

Hodkinson H: Abbreviated mental test score. Age Ageing. 1972, 1: 223-238.

Hill KD, Schwarz JA, Kalogeropoulos AJ, Gibson SJ: Fear of falling revisited. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996, 77 (10): 1025-1029. 10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90063-5.

Hayes V, Morris J, Wolfe C, Morgan M: The SF-36 health survey questionnaire: is it suitable for use with older adults?. Age Ageing. 1995, 24 (2): 120-125. 10.1093/ageing/24.2.120.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993, 31 (3): 247-263. 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994, 32 (1): 40-66. 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004.

Scott KM, Tobias MI, Sarfati D, Haslett SJ: SF-36 health survey reliability, validity and norms for New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999, 23 (4): 401-406.

Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB: A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994, 49 (2): M85-94.

Rossiter-Fornoff JE, Wolf SL, Wolfson LI, Buchner DM: A cross-sectional validation study of the FICSIT common data base static balance measures. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995, 50 (6): M291-7.

Hill K, Schwarz J, Flicker L, Carroll S: Falls among healthy, community-dwelling, older women: a prospective study of frequency, circumstances, consequences and prediction accuracy. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999, 23 (1): 41-48.

Nouri FM, Lincoln NB: An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 1987, 1: 301-305.

Essink-Bot ML, Krabbe PF, Bonsel GL, Aaronson NK: An empirical comparison of four generic health status measures. The Nottingham Health Profile, the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-form Health Survey, the COOP/WONCA charts, and the EuroQol instrument. Med Care. 1997, 35 (5): 522-537. 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00008.

Elley CR, Kerse NM, Swinburn B, Arroll B, Robinson E: Measuring physical activity in primary health care research: validity and reliability of two questionnaires. N Z Fam Physician. 2003, 30 (3): 171-180.

Drummond MF, O'Brien WL, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 1997, New York , Oxford University Press, 2nd

Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, Koch ML, Trainor K, Horwitz RI: A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994, 331 (13): 821-827. 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301.

Accident Compensation Corporation: Otago Exercise Programme to prevent falls in older adults. [http://www.acc.co.nz/otagoexerciseprogramme]

Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ: Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327 (23): 1637-1642.

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE: Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996, 348 (9041): 1535-1541. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07088-2.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S: The timed "Up & Go": A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991, 39: 142-148.

MacEntee MI, Wyatt C, Kiyak HA, Hujoel PP, Persson RE, Persson GR, Powell LV: Response to direct and indirect recruitment for a randomised dental clinical trial in a multicultural population of elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002, 30 (5): 377-381. 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.00003.x.

Ivers RQ, Norton R, Cumming RG, Butler M, Campbell AJ: Visual impairment and risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 152 (7): 633-639. 10.1093/aje/152.7.633.

Okumiya K, Matsubayashi K, Nakamura T, Fujisawa M, Osaki Y, Doi Y, Ozawa T: The timed "Up & Go" test and manual button score are useful predictors of functional decline in basic and instrumental ADL in community-dwelling older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999, 47 (4): 497-498.

Rockwood K, Awalt E, Carver D, MacKnight C: Feasibility and measurement properties of the functional reach and the timed up and go tests in the Canadian study of health and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000, 55 (2): M70-3.

Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB: Falls in older people: risk factors and strategies for prevention. 2001, Cambridge, United Kingdom , Cambridge University Press

Kenny RA: Neurally mediated syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002, 18 (2): 191-210, vi. 10.1016/S0749-0690(02)00005-8.

Davies AJ, Steen N, Kenny RA: Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is common in older patients presenting to an accident and emergency department with unexplained falls. Age Ageing. 2001, 30 (4): 289-293. 10.1093/ageing/30.4.289.

Kenny RA, Richardson DA, Steen N, Bexton RS, Shaw FE, Bond J: Carotid sinus syndrome: a modifiable risk factor for nonaccidental falls in older adults (SAFE PACE). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 38 (5): 1491-1496. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01537-6.

Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT: Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995, 273 (17): 1348-1353. 10.1001/jama.273.17.1348.

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B: Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004, 15 (3): 175-179. 10.1007/s00198-003-1514-0.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/7/185/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Nita Hill, Jenny Bush, Lindsay Macdonald and Jessica Robinson for their contribution to the study. We acknowledge the primary health care practices that participated in the trial, Kowhai Health Trust, Woburn Masonic Rehabilitation Home, and the physiotherapists and nurses who delivered the Otago Exercise Programme to intervention participants. We acknowledge the Hutt Valley District Health Board for their advice and support. We thank the Accident Compensation Corporation for their continued support, as well the many community based allied health professionals and others that have contributed to the intervention and to the study.

The trial was funded by the Accident Compensation Corporation, the Hutt Valley District Health Board, the Lotteries Commission, and the Wellington Medical Research Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CRE contributed to design, supervised all aspects of the study, contributed to analyses and interpretation of results, and drafted the manuscript. MCR contributed to the design, random sequence generation, analysis, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. NK contributed to the design, interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript. SG contributed to data collection and management, project management, analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. EM contributed to the study design, data collection supervision, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. BL advised on study design, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. HM contributed to the design of the study, intervention set-up, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. AJC conceived of the intervention, contributed to the design, interpretation and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Elley, C.R., Robertson, M.C., Kerse, N.M. et al. Falls Assessment Clinical Trial (FACT): design, interventions, recruitment strategies and participant characteristics. BMC Public Health 7, 185 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-185

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-185