Abstract

Background

While extensive research has been conducted on bullying and victimization in western countries, research is lacking in low- and middle-income settings. This study focused on bullying victimization in Peru. It explored the relationship between the caregiver’s perception of child victimization and the child’s view of selected negative experiences occurring with other children their age. Also, the study examined the association between victimization and adolescent health risk behaviors.

Methods

This study used data from 675 children participating in the Peru cohort of the Young Lives study. Children and caregivers were interviewed in 2002 when children were 8 years of age and again in 2009 when children were 15 years of age. Measures of victimization included perceptions from children and caregivers while measures of health risk behaviors included cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations among adolescents.

Results

Caregivers identified 85 (12.6%) children bullied at ages 8 and 15, 235 (34.8%) bullied at age 8 only, 61 (9.0%) bullied at age 15 only, and 294 (43.6%) not bullied at either age. Children who were bullied at both ages compared with all other children were 1.58 (95% CI 1.00-2.50) times more likely to smoke cigarettes, 1.57 (1.04-2.38) times more likely to drink alcohol, and 2.17 (1.41-3.33) times more likely to have ever had a sexual relationship, after adjusting for gender. The caregiver’s assessment of child victimization was significantly associated with child reported bullying from other children their age. Child reported victimization was significantly associated with increased risky behaviors in some cases.

Conclusion

Long-term victimization from bullying is more strongly associated than less frequent victimization with increased risk of cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations at age 15. Hence, programs focused on helping children learn how to mitigate and prevent bullying consistently over time may also help reduce risky adolescent health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and sexual activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bullying during childhood and adolescence is a common experience that has potentially far reaching negative implications [1–3]. Bullying is a broad construct that is manifested by deliberate antagonistic behavior by the bully towards the victim, persistence of this behavior over a period of time, and an imbalance of power between the bully and the victim [4–8]. Bullying is often characterized as either direct—personal confrontation between the bully and the victim—or indirect—passive interaction such as social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber-bullying [8–13].

Bullying and victimization among children are associated with high-risk health behaviors such as substance abuse, sexual activity, and suicidal ideation and attempts [14–16]. In a study focusing on middle and high school youth, substance abuse (alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana) was greater among both those perpetuating the bullying and the victims, with greater use occurring among victims [14]. Earlier studies have also found an association between bullying and substance abuse [17–19]. Recent associations between bullying and increased sexual activity have similarly been identified [20, 21].

Bullying is a global problem, with between 10 and 30 percent of youth involved in some aspect of bullying (bully and/or victim) [5]. High levels of bullying exist throughout the U.S. [19, 22, 23], Europe [24, 25], Australia [26], and Latin America [27–29]. Data from the 2005 Health Behavior in School-aged Children survey, a representative sample of grades 6-10 in the United States, showed that bullying in the past two months was commonly done through direct and indirect ways: physical (21%), verbal (54%), social (51%), and electronically (14%) [23].

Bullying and victimization is less understood in low- to middle-income countries due to less available data. In several Latin American countries, early studies show the prevalence of bullying to be as high as 50%. In Peru and Colombia, for example, bullying among teens may involve as much as half of the population [28–32]. Studies show that bullying among Peruvian adolescents is both physical and psychological, involves more males than females, and is most frequent between the ages of 10-16 [33, 34]. In 50 cities throughout Peru, researchers found that of the students who reported being bullied, 54.4% were bullied verbally, 35.9% were involved in physical aggression, 26.7% were excluded from groups, and 12.8% were bullied by mixed forms of violence [32]. A 2008 study reported that 47% of Peruvian teenagers were bullied [28]. However, this study noted that a third of the students did not tell a parent or a teacher of the bullying incident, indicating that the level of bullying may be much higher and that caregivers may largely be unaware of the extent of this problem.

The current study focused on bullying victimization among a Peruvian cohort. It explored the relationship between the caregiver’s perception of child bullying, how this perception related to the child’s view of selected negative experiences with other children their age, and how these experiences related to cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations. Specifically, the study examined if the caregiver’s assessment of bullying at ages 8 and 15 associated with increased risk of current cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking and ever having had sexual relations for children aged 15 years. The study also evaluated whether child-specific items involving negative associations with other children of a similar age were related to the caregiver’s assessment of their child being bullied. Lastly, the study assessed whether child-specific items involving negative associations with other children of a similar age were related to cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and having ever had sexual relations among children aged 15 years.

Methods

Young lives

Young Lives is an international prospective study of childhood poverty, education, and health among approximately 12,000 children in four countries: Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. A detailed description of the study design, methods for sampling, recruitment, and interviewing are described in detail elsewhere [35]. In brief, the Young Lives study followed two cohorts of children in each country, a younger cohort of 2,000 children who were recruited at approximately 1 year of age and an older cohort of approximately 1,000 children enrolled at 8 years of age. This study focused on data from the older Peruvian cohort.

Peruvian children were randomly selected from 74 communities within 20 random districts comprising the poorest 95% of districts in Peru. Children and caregivers were interviewed at enrollment (Round 1), in 2006 (Round 2), and again in 2009 (Round 3) when children were ages 8, 12, and 15, respectively. Fieldworkers were trained extensively prior to data collection to standardize data collection protocols. This study used data from 675 children and caregivers for whom data was available when the child was 8 and 15 years of age.

Measures

The caregiver’s assessment of bullying is based on the question: “Is NAME, picked on or bullied by other children?” This question was asked at ages 8 and 15. For part of the analysis, the association between the combinations of bullying at the two ages (yes-yes, yes-no, no-yes, and no-no) with cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations were evaluated. At age 15, eight child-specific items involving negative associations with other children their age were asked to the children. They were told to indicate their level of experience with each of these items: never, once, 2-3 times, or 4+ times. In some cases, responses were dichotomized as never/once and 2+ times to improve analytical power. Questions about current cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and whether they had ever had a sexual relationship were asked to the children at age 15.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the Young Lives study was granted by London South Bank University, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the University of Reading and from the IIN. Approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham Young University. Only households that provided informed consent were included.

Statistical techniques

Incidence rates were used to summarize the data and describe distributions. The assessment of bullying at ages 8 and 15 by caregivers were evaluated using McNemar’s chi-square test. Independence between categorical variables was evaluated for statistical significance using the chi-square test. The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square was used to evaluate trends. Relative risks were calculated to compare incidence between groups. These ratios were adjusted for gender and evaluated for statistical significance using 95% confidence intervals. Three multivariate regression analyses were conducted involving child-perceived negative behavior variables regressed on cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and then sexual relations, adjusted for gender. Each of these models was significant based on Wilks’ Lambda, indicating that it was appropriate to do bivariate analyses on these variables. Finally, multiple Poisson regression was used to simultaneously assess the significance of a combination of child-perceived negative behavioral items on caregiver assessment of bullying, current cigarette smoking, current alcohol drinking, and ever having had a sexual relationship. Two-sided tests of hypotheses were evaluated using the 0.05 level of significance. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 2010).

Results

Bullying status, as reported by the caregiver, significantly changed from age 8 (320, 47.4%) to age 15 (146, 21.6%) based on the McNemar test (p < 0.0001). The combination of bullying status at ages 8 and 15 is shown in Table 1. At age 15, questions were first asked about the children’s smoking, alcohol, and sexual behaviors, wherein 18.1% (26.2% of males and 10.9% of females, p < 0.0001) smoked cigarettes, 36.6% (37.5% for males and 36.3% for females, p = 0.7299) drank alcohol, and 24.5% (31.4% for males and 17.4% for females, p < 0.0001) had engaged in sexual relations. Children who caregivers reported were bullied at both ages 8 and 15 had a significantly greater level of smoking, drinking, and past sexual experience at age 15. Children bullied at age 8 but not age 15, or not at age 8 but at age 15, were less likely to smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, or have had a sexual relationship. Children who were bullied at both ages 8 and 15 compared with the other groups of children, adjusting for gender, were 1.58 times more likely to smoke cigarettes, 1.57 times more likely to drink alcohol, and 2.17 times more likely to have had a sexual relationship.

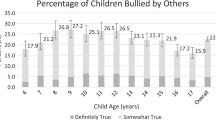

More than half (59.4%) of children reported having others stealing something from them at age 15 (Table 2). The least common forms of child-reported negative experiences at age 15 were physical harm or damaging one’s property. Using multiple Poisson regression to test for agreement between caregiver report of bullying and child-reported bullying, model estimates indicated that three of the eight child-reported items were significantly associated with caregiver report of child being bullied at age 15 and at both ages 8 and 15: “Tried to get you into trouble with your friends,” “Made fun of you for some reason,” and “Punched, kicked, or beat you up” (data not shown). Caregiver report of child being bullied at both ages 8 and 15 compared with those not bullied at either age were significantly more likely to be punched, kicked or beat up at age 15 (Relative Risk = 2.52, 95% CI = 1.40-4.53). Those bullied at age 8 but not at age 15 compared with not bullied at either age were not significantly more likely to experience any of the items in Table 2. In a third model, those not bullied at age 8 but bullied at age 15 compared with not bullied at either age were significantly more likely to have someone try to get them in trouble with their friends (Relative Risk = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.27-2.99). All three models adjusted for gender.

Multivariate regression analysis was conducted with each of the eight variables of child-reported negative experience, simultaneously regressed on the cigarette smoking variable, adjusted for gender, which gave a Wilks’ Lambda p = 0.0478. Similar models were run for alcohol (< 0.0001), and sexual relations (0.0180). Relative risks adjusted for gender are presented for each of the eight items in Table 3.

The incidence of cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations was associated with a number of child-specific items involving negative experiences with other children their age. Two key items, “Tried to get you in trouble with your friends” and “Hurt you physically in any other way” were significantly positively associated with cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and sexual relations. The incidence of alcohol drinking and sexual relations were additionally associated with items measuring being made fun of, refusing to talk to, and made uncomfortable by staring at you for a long time. “Taken something without permission or stolen from you” or “Tried to break or damage something of yours” were not significantly associated with cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, or sexual relations.

Using multiple Poisson regression, two items, “Tried to get you in trouble with your friends” and “Punched, kicked or beat you up”, as well as gender, were consistently associated with both cigarette smoking and sexual relations (Table 4). The first item was also associated with drinking alcohol. Interaction terms involving the two items were not significant in any of the models.

Discussion

This study addressed three specific research questions involving bullying victimization and substance use among children in Peru. The first question explored whether the caregiver perceived bullying at both ages 8 and 15 was associated with increased risk of cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and having ever had sexual relations for children aged 15 years. Although previous research has shown that bullying victimization is associated with increased risk for addictive behaviors, such as smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol [36, 37], this study found that only children identified by caregivers as being bullied at both ages 8 and 15 were significantly more likely to smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, and have had sexual relations at age 15. Those who were bullied at just age 8 or just age 15 had levels of smoking, drinking and sexual relations similar to those who had never been bullied. This indicates that long-term bullying is more predictive of substance use and sexual relations. While preventing bullying entirely remains a primary objective, this finding highlights the benefit and importance of limiting the duration of bullying to a short-term and infrequent occurrence. Perhaps most importantly, this finding provides substantial hope that mediating interventions targeted at those who have experienced bullying in the short-term can help prevent adolescent health risk behaviors.

The second research question explored whether child-specific items involving negative associations with other children of a similar age were related to the caregiver’s assessment of their child being bullied. Indirect forms of bullying victimization were more common than direct forms [8–13]. Increasing frequency of child-reported negative experiences was associated with caregiver indication of child bullying for the items: “Tried to get you into trouble with your friends,” “Made fun of you for some reason,” and “Punched, kicked, or beat you up.” “Hurt you physically in any other way” was marginally insignificant. This is generally consistent with previous research demonstrating that while a majority of children do tell their parents when they are bullied, a substantial amount (roughly 1 in 3) do not and that children who were bullied more frequently were more likely to tell their parents [38]. Hence, while caregiver perceptions of peer-victimization is a good predictor of actual child victimization, not all children tell their parents, particularly those who experience less peer victimization. These findings demonstrate a need for empowering children with improved decision-making and communication skills while encouraging them to speak with a trusted adult or caregiver whenever bullying occurs. Additionally, these findings highlight the challenge for researchers in identifying additional measures for both identifying and quantifying early childhood bullying. Further, this research indicates a gap between various types of child-reported victimization and victimization recognized by caregivers. Establishing better measures of bullying behaviors together with helping adults and children accurately define and recognize bullying behaviors provides promise in narrowing this gap [39]. Future efforts might also be directed at improving communications between children and caregivers regarding the topic of bullying victimization.

This study also assessed whether the child-specific items involving negative associations with other children of a similar age related to current cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and having ever had sexual relations among children aged 15 years. One study found that all forms of bullying increases the risk of smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol [40]. This differs from the findings of the current study which demonstrated that long-term bullying associated more with smoking, drinking, and sexual relations, and that only “Tried to get you into trouble with your friends” and “Punched, kicked or beat up” had independent direct effects on smoking and sexual relations with the first item also associated with alcohol drinking. Although other research among children in third grade has found that experiencing both relational and physical aggression had the greatest risk for maladjustment a year later [20], the models utilized in the current study did not find a similar interaction effect. Although slight variations in associations among bullying measures and behaviors exist between previous research and the current study, the current findings strongly support the association between bully victimization and adolescent health risk behaviors.

Children try to fit in and be well-liked by their peers. One study observed that victims of bullying are more likely to become bullies themselves [27]. Perhaps this is an attempt to fit in and be accepted. Along the same lines, victims of bullying may be more likely to turn to smoking, alcohol drinking, or sexual activity as a way to be accepted by peers. Turning to these health risk behaviors during adolescence may be a coping strategy employed to deal with their victimization.

This study has several limitations. Young Lives is a study of poverty and was not designed to explore the correlates of bullying in-depth. However, Young Lives does contain a richness of data collected longitudinally that is not typically available in low-resource settings. Further, while this study has multiple time points over adolescence, much is not known about what happens to the child between measurement periods. As a result, this study provides important information on the possible pathways that connect bullying and risky behaviors, but falls short of constructing a complete picture.

Conclusion

In summary, persistent bullying across time is associated with increased adolescent health risk behaviors compared to those who experienced bullying only at one time or not at all. Hence, programs focused on teaching children how to mitigate and prevent bullying consistently over time may also help reduce adolescent health risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and sexual activity. Further, this research demonstrates that while there is need for improvement, caregivers are generally attuned to specific child victimization experiences. However, more research is needed to understand how children make decisions on when to disclose such experiences to caregivers and how to increase and improve such communication.

Authors’ information

BC, JW, and PH are assistant professors in the Department of Health Science at Brigham Young (BYU) University. RM is a professor in the Department. SH is an undergraduate student in Public Health at BYU and CL is a Master of Public Health Student at BYU.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MH:

-

Mantel-Haenszel.

References

Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel DD, Floyd CF, Vagi KJ: Precipitating circumstances of suicide among youth aged 10-17 years by sex: data from the national violent death reporting system, 16 States, 2005-2008. J Adolesc Health. 2013, 53 (1 Suppl): S51-S53.

Bowes L, Maughan B, Ball H, Shakoor S, Ouellet-Morin I, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L: Chronic bullying victimization across school transitions: the role of genetic and environmental influences. Dev Psychopathol. 2013, 25: 333-346. 10.1017/S0954579412001095.

Sesar K, Barišić M, Pandža M, Dodaj A: The relationship between difficulties in psychological adjustment in young adulthood and exposure to bullying behaviour in childhood and adolescence. Acta Med Acad. 2012, 41: 131-144. 10.5644/ama2006-124.46.

Olweus D: Bullying or peer abuse at school: facts and intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1995, 4: 196-200. 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772640.

Smith PK, Cowie H, Olafsson RF, Liefooghe APD: Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen–country international comparison. Child Dev. 2002, 73: 1119-1133. 10.1111/1467-8624.00461.

Maunder RE, Harrop A, Tattersall AJ: Pupil and staff perceptions of bullying in secondary schools: comparing behavioural definitions and their perceived seriousness. Edu Res. 2010, 52: 263-282. 10.1080/00131881.2010.504062.

Frisén A, Holmqvist K, Oscarsson D: 13-year-olds’ perception of bullying: definitions, reasons for victimisation and experience of adults’ response. Edu Stud. 2008, 34: 105-117. 10.1080/03055690701811149.

Espelage DL, Swearer SM: Research on school bullying and victimization: what have we learned and where do we go from here?. School Psychol Rev. 2003, 32: 365-383.

Cook CR, Williams KR, Guerra NG, Kim TE, Sadek S: Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic investigation. School Psychol Quart. 2010, 25: 65-83.

Wang J, Ianotti RJ, Luk JW: Bullying victimization among underweight and overweight U.S. Youth: differential associations for boys and girls. J Adolescent Health. 2010, 47: 99-101. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.007.

Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ: Twenty Years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Child Psychol & Psychiat & Allied Discipl. 2000, 41: 441-455. 10.1111/1469-7610.00629.

Boulton MJ, Trueman M, Flemington I: Associations between secondary school Pupils’ definitions of bullying, attitudes towards bullying, and tendencies to engage in bullying: age and sex differences. Edu Stud. 2002, 28: 353-370. 10.1080/0305569022000042390.

Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, Schultz H: Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: prevalence and school factors. Br J Psychol. 2001, 92: 673-696. 10.1348/000712601162419.

Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, Morris J: Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addict Behav. 2012, 37: 569-572. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.001.

Hepburn L, Azrael D, Molnar B, Miller M: Bullying and suicidal behaviors among urban high school youth. J Adolescent Health. 2012, 51: 93-95. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.014.

Klomek AN, Sourander A, Niemela S, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Almqvist F, Gould MS: Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009, 48: 254-261. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f.

Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM: Childhood conduct problems, attention deficit behaviors, and adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995, 23: 281-302. 10.1007/BF01447558.

Choquet M, Menke H, Manfredi R: Interpersonal aggressive behavior and alcohol consumption among young urban adolescents in France. Alcohol Alcoholism. 1991, 26: 381-390.

Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Rilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P: Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001, 285: 2094-2100. 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094.

Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Werner NE: A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and Children’s social–psychological adjustment. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006, 34: 127-138. 10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4.

Williams T, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W: Questioning and sexual minority adolescents: high school experiences of bullying, sexual harassment and physical abuse. Can J Comm Ment Health. 2003, 22: 47-58.

Shetgiri R, Lin H, Flores G: Trends in risk and protective factors for child bullying perpetration in the United States. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013, 44: 89-104. 10.1007/s10578-012-0312-3.

Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR: School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Health. 2009, 45: 368-375. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021.

Lien L, Green K, Welander-Vatn A, Bjertness E: Mental and somatic health complaints associated with school bullying between 10th and 12th grade students; results from cross sectional studies in Oslo, Norway. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009, 5 (1): 6-10.1186/1745-0179-5-6.

Analitis F, Velderman MK, Ravens-Sleberer U, Detmar S, Erhart M, Herdman M, Berra S, Alonso J, Rajmil L, European Kidscreen Group: Being bullied: associated factors in children and adolescents 8 to 18 years Old in 11 European countries. Pediatrics. 2009, 123: 569-577. 10.1542/peds.2008-0323.

Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Herrenkohl TI, Bond L, Kim MJ, Toumbourou JW, Catalono RF: Longitudinal consequences of adolescent bullying perpetration and victimisation: A study of students in Victoria, Australia. Crim BehavMent Health. 2011, 21: 107-116. 10.1002/cbm.802.

Muula AS, Herring P, Siziya S, Rudatsikira E: Bullying victimization and physical fighting among Venezuelan adolescents in Barinas: results from the Global School-Based Health Survey 2003. Ital J Pediatr. 2009, 35: 38-38. 10.1186/1824-7288-35-38.

Oliveros M, Figueroa L, Mayorga G, Cano G, Quispe Y, Barrientos A: Violencia escolar (bullying) en colegios estatales de primaria en el Perú. Rev Peru Pediatr. 2008, 61: 215-220.

Oliveros M, Figueroa L, Mayorga G, Cano B, Quispe Y, Barrientos A: Intimidación en colegios estatales de secundaria del Perú. Rev Peru Pediatr. 2009, 62: 68-78.

Donohue MO, Achata AB: Incidencia y factores de riesgo de la intimidación (bullying) en un colegio particular de Lima-Perú, 2007. Rev Peru Pediatr. 2007, 60: 150-155.

Amemiya I, Oliveros M, Barrientos A: Factores de riesgo de violencia escolar (bullying) severa en colegios privados de tres zonas de la sierra del Perú. A Fac Med. 2009, 70: 255-258.

Romaní F, Gutiérrez C, Lama M: Auto-reporte de agresividad escolar y factores asociados en escolares peruanos de educación secundaria. Rev Peru Epidemiol. 2011, 15 (2): 8-8.

Merino C, Carozzo J, Benites L: The conspiracy of silence: the bullying in Peru. The Handbook of School Violence and School Safety: International Research and Practice. Edited by: Jimerson SR, Nickerson MJ, Mayer MJ, Furlong MJ. 2011, New York (NY): Routledge, 153-164. 2

Pellegrini AD, Bartini M: A longitudinal study of bullying, victimization, and peer affiliation during the transition from primary school to middle school. Am Educ Res J. 2000, 37 (3): 699-725. 10.3102/00028312037003699.

Young Lives: An international study of childhood poverty. Retrieved from http://www.younglives.org.uk

Houbre B, Tarquinio C, Thuillier I: Bullying among students and its consequences on health. Europ J Psychol Educ. 2006, 21: 183-208. 10.1007/BF03173576.

Hazemba A, Siziya S, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E: Prevalence and correlates of being bullied among in-school adolescents in Beijing: results from the 2003 Beijing Global School-Based Health Survey. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2008, 7 (6):

Fekkes M, Pijpers FI, Verloove-Vanhorick SP: Bullying: who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Educ Res. 2005, 20 (1): 81-91.

Hamburger ME, Basile KC, Vivolo AM: Measuring bullying victimization, perpetration, and bystander experiences: A compendium of assessment tools. 2011, Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

Vieno A, Gini G, Santinello M: Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in Italian adolescents. J Sch Health. 2011, 81 (7): 393-399. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00607.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/85/prepub

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study come from Young Lives, a 15-year survey investigating the changing nature of childhood poverty in Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh), Peru and Vietnam (http://www.younglives.org.uk). Young Lives is core-funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID) and co-funded from 2010 to 2014 by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BC acquired the data and BC and RM conceived the design of the study. RM completed the analysis and wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to the writing and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Crookston, B.T., Merrill, R.M., Hedges, S. et al. Victimization of Peruvian adolescents and health risk behaviors: young lives cohort. BMC Public Health 14, 85 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-85

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-85