Abstract

Background

Low socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood is known to be a significant risk factor for mental disorders in Western societies. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether a similar association exists in Japan.

Methods

We used data from the World Mental Health Japan Survey conducted from 2002–2006 (weighted N = 1,682). Respondents completed diagnostic interviews that assessed lifetime prevalence of major depression (MD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Associations between parental education (a proxy of SES in childhood) and lifetime onset of both disorders were estimated and stratified by gender using discrete-time survival analysis.

Results

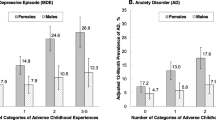

Among women, high parental education was positively associated with MD (odds ratio [OR]: 1.81, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03-3.18) in comparison with low parental education, even after adjustment for age, childhood characteristics, and SES in adulthood. This same effect was not found for men. In contrast, higher parental education was associated with GAD (OR: 6.84, 95% CI: 1.62-28.94) in comparison with low parental education among men, but this association was not found among the women, in the fully adjusted model.

Conclusions

In Japan, childhood SES is likely to be positively associated with the lifetime onset of mental disorders, regardless of family history of mental disorders, childhood physical illness, or SES in adulthood. Further study is required to replicate the current findings and elucidate the mechanism of the positive association between mental disorders and childhood SES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is widely known that low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety disorders [1–5]. This association can be explained in two ways: (1) low SES actually induces a mental disorder (social causation); or (2) mental disorders limit employment opportunities, causing individuals to fall into the low SES category (health selection) [6, 7].

Previous studies have shown that SES in childhood has a direct effect on the development of mental disorders later in life [8–15]. For example, Gilman et al. reported that participants whose parent was engaged in manual labor either at the time of their birth or when they were seven years old were significantly more likely to develop major depression (MD) in their lifetime, even after adjusting for SES in adulthood [11]. However, since most of these studies were performed in Western countries, it is uncertain whether a similar association exists in Japan, where SES likely affects mental disorders differently [16, 17]. For instance, while education has been found to be inversely associated with depression in the USA, no such association has been found in Japan [16].

MD and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) must be addressed in particular, in view of their high prevalence [18, 19]. The lifetime prevalence of MD and GAD in the US is 16.6% and 5.7%, respectively in 2001–2003 [18], and in Japan, 4.4% for MD in 2005 [20]. Because MD and GAD are associated with several major causes of death, such as suicide [21] or cardiovascular disease [22, 23], and greater disability-adjusted life years [24], further prevention efforts are needed. An investigation into the associations between childhood SES and MD or GAD may provide crucial information concerning the possible etiologies of these disorders. Further, by stratifying the data according to gender, the higher prevalence of these disorders among women may be explained [11].

Against these backgrounds, we hypothesized that childhood SES is associated with the lifetime onset of mental disorders, regardless of family history of mental disorders, childhood physical illness, or SES in adulthood, based on life-course epidemiology [25]. By focusing on SES in childhood, we can include the early onset cases, which are usually excluded in studies of the association between SES in adulthood and mental disorders in order to avoid reverse causation [26]. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether SES in childhood was associated with MD and GAD in both adult men and women.

Methods

Sample

Data from the World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey conducted between 2002 and 2006 were used. The WMHJ conducted an epidemiological survey of Japanese people aged 20 years and older as part of the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative [27]. Details of the WMHJ survey design, sampling, and field procedures have been described in previous research [28].

Three urban cities and eight rural municipalities in Japan were selected as study sites. These sites were selected because of their geographic variation, the availability of site investigators, and the cooperation of local government officials. Participants were randomly selected from a pool of eligible voters (i.e., registered residents) aged 20 years or older.

An internal sampling strategy was used to reduce respondent burden by dividing the interview into two parts. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment (details given below) and obtained the demographic variables of all the respondents. Part II included questions about risk factors, including childhood SES. Part II was administered to 1,682 of the 4,134 individuals who responded to the questionnaire in Part I (including all respondents with one or more lifetime disorders, as well as a probability subsample of approximately 25% of the other respondents). The total response rate was 55.1%. This sampling method was not significantly different from those used in the World Mental Health Surveys conducted in other countries [29].

The data were weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and non-response (Weighted N = 1,682; N [men] = 734; N [women] = 948). Details of sample weights have been reported previously [19]. Sample size was calculated by assuming the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders to be between 5 and 10% [29] in low and high childhood SES groups with equal distribution ratios (with a Type I error = 0.05 and Type II error = 0.2), respectively. This yielded a figure of 948 participants who were able to successfully complete this study.

Written consent was obtained from every respondent at all study sites. The survey recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by The Human Subjects Committees of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences, the Japan National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Nagasaki University’s Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Yamagata University’s Graduate School of Medical Science, and Juntendo University’s Graduate School of Medicine.

Diagnostic assessment

The WMHJ used a Japanese-translated, computer-assisted version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Version 3.0 (WHO-CIDI 3.0) to assess mental disorders in individuals according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [27]. Details concerning the translation process from English to Japanese have been reported previously [19]. Lifetime diagnoses of MD and GAD were approximated by the presence or absence of diagnoses of these disorders that respondents admitted to having, up to the time of the interviews. Diagnostic hierarchy and organic exclusion rules were used for making diagnoses.

The CIDI retrospectively assessed the age of onset for the disorders; however, in view of the existing evidence that retrospective age-of-onset reports are often biased [30], a special question sequence (previously used in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication) was introduced to improve the accuracy of reporting. In brief, the age of onset reported by the respondents was confirmed by other sequential questions, such as “Was it before you went to school?”. Onset age was set at the upper end of the bound of uncertainty (e.g., age: 12 years for respondents who reported that onset was before their teenage years). Previous research has shown that this question sequence yields more credible responses than do standard age-of-onset questions [31].

Socioeconomic status in childhood

SES in childhood was measured using the proxy variable of parents’ education, because parental education is usually determined before the birth of the respondent; thus, we can use this measure to assess the impact of childhood SES on the lifetime incidence of MD or GAD. The number of years of education for both parents was surveyed, and the responses were categorized into three groups: less than a high school (0–11 years), high school (12 years), and some college or more (≥13 years). If the number of years of education was unknown, this became a dummy variable. If a respondent’s parents’ years of education were in discord, we used the higher number of years as parental education for our study.

Covariates

Under the assumption that they could be possible confounders or mediators in the relationship between childhood SES and lifetime onset of MD and GAD, we assessed data on certain childhood characteristics and SES in adulthood. The childhood characteristics of interest included parental mental illness and the presence of personal physical illness in the respondent’s childhood (based on responses to yes/no questions). SES in the respondents’ adulthood was measured by the individual’s number of years of education, categorized into less than high school (0–11 years), high school (12 years), some college (13–15 years), and college or more (≥16 years). Further, the respondent’s current annual household income was categorized with reference to the poverty line in Japan [32, 33], as either low (<3 million yen), middle (3–9.9 million yen), or high (≥10 million yen).

Analysis methods

The models were estimated in a discrete-time survival framework with person-years as the unit of analysis. The obtained person-oriented data set (containing information on the age of onset for each mental disorder) from the cross-sectional survey was converted into a person-period dataset (containing information on each discrete time period for the individual, censoring the onset of each mental disorder) [34]. Each model was controlled for person-years, age category, and covariates. The survival coefficients and their standard errors (SEs) in the best-fitting model were exponentiated and are reported in the form of odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Model 1 was adjusted for age, Model 2 included information in Model 1 plus childhood characteristics (parental mental illness and childhood physical illness), while Model 3 included the information in Model 2 plus SES in adulthood (educational attainment and annual household income). All analyses were stratified by gender. STATA MP 12 was used for the analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the sample population

Table 1 shows the mean ages of the men and women subjects were 50.1 (SE = 0.91) and 52.2 years (SE = 0.92) respectively, distributed normally. Regarding high SES in childhood, parental education was ≥13 years for 15.4% of the men and 11.7% of the women, although a significant portion of the participants did not know their parental educations (26.4% of the men and 28.3% of the women).

In terms of childhood characteristics, less than 5% of respondents across both genders reported having parents with psychiatric illnesses or having their own physical illnesses in childhood. As for SES in adulthood, 27.9% of the men and 11.4% of the women graduated from college or achieved some other level of higher education. Further, 18.3% of the men and 11.5% of the women earned more than 10 million yen per year. Finally, 4.7% of the men and 8.7% of the women developed MD, while 2.8% of the men and 3.0% of the women developed GAD during their lifetimes.

Association of SES with MD

Table 2 shows the ORs of childhood SES for MD among men. SES in childhood (i.e., parental education) was not associated with MD in Model 1 (adjusting for age), Model 2 (plus adjustment for childhood characteristics), or Model 3 (plus adjustment for SES in adulthood). Among the covariates, having a physical illness in childhood and a higher educational attainment (i.e., ≥16 years) were significantly independently associated with the onset of MD. That is, those who had physical illness in childhood were 2.89 (95% CI: 1.00-8.32) times more likely to develop MD than those who did not, and those who attained ≥16 years of education were 3.14 (95% CI: 1.08-9.14) times more likely to develop MD than those who attained 0–11 years of education.

In contrast, among women, high SES in childhood (i.e., parental education that went beyond high school), was positively associated with the onset of MD (Table 3), and this relationship was quite robust. Participants with high parental education were 1.85 (95% CI: 1.00-3.42) times more likely to develop MD than those whose parental education was lower than high school in Model 2, which was slightly attenuated in Models 3. Among other covariates, those who attained high school education were more likely to develop MD than those who attained education level lower than high school (OR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.19–4.81).

Association of SES with GAD

Table 4 shows the ORs of childhood SES for GAD among men. Higher parental education was significantly associated with the onset of GAD. Those whose parental education was high school or beyond high school were 5.63 (95% CI: 1.16–27.41) and 8.47 (95% CI: 1.87-38.37) times more likely to develop GAD, respectively, than those whose parental education was lower than high school in Model 1, which was slightly attenuated after adjusting for childhood characteristics and SES in adulthood (Model 3). In contrast to the results for MD, no association was found between the onset of GAD and childhood physical illness.

On the other hand, among women, no association was found between childhood SES and the onset of GAD (Table 5). Moreover, no other covariates had any significant association with the onset of GAD, including SES in adulthood.

We also estimated our model excluding unknown parental education cases in order to complete a sensitivity analysis. No substantial change in our results was found.

Discussion

Unlike what has been found in previous studies in Western societies [8–13], we found that, among women, higher SES in childhood is positively associated with the onset of MD, but not GAD, even after adjusting for age, childhood characteristics, and SES in adulthood. In contrast, higher childhood SES among men is associated with GAD, but not with MD, after fully adjusting for other covariates. High SES in adulthood, represented as educational attainment, is also positively associated with MD for both genders.

Our results indicate that high SES in childhood has a direct effect on the onset of mental disorders in Japan. Previous studies on SES and mental disorders in Japan have reported inconsistent results; that is, higher educational attainment may [35] or may not be [16, 17] associated with mental disorders. In our study, high childhood SES was positively associated with the onset of mental disorders (more precisely, MD and GAD); however, the exact mechanism of this positive association is unknown. Asian parents tend to have stronger expectations for their children [36, 37] in terms of educational achievements than do Western parents [38]. Similarly, Japanese parents, particularly those in higher SES families, have high expectations for their children [39, 40]. Therefore, it is likely that those who come from high parental SES situations may feel more pressure to achieve; thus, they may feel distressed when they fail to do so into adulthood. Moreover, those who come from a high-SES family may have been overprotected during childhood, a phenomenon that has been shown to induce lower stress tolerance [41, 42]. Thus, when they encounter stressful academic, professional, or social situations, they are more likely to develop mental disorders.

The impact of high SES in childhood has specific associations by gender and disorder. High childhood SES is associated with MD only among women, and it is associated with GAD only among men. This is probably due to gender differences in stress response [43]. Women tend to internalize stress and feel disappointment or decreased self-esteem when they face stressful situations [44–46]. Thus, women who experienced high SES in childhood are more likely to develop MD. Meanwhile, men with higher SES in childhood might feel more pressure and a heightened sense of personal responsibility when they enter middle age, resulting in the development of GAD. Previous studies have shown that childhood SES is positively associated with average levels of educational and occupational expectations throughout adulthood [47, 48]. Furthermore, qualitative study is needed to confirm how women or men with high childhood SES deal with that stress.

Our results showed that respondents’ educational attainment had independent associations with MD, regardless of gender. The directionality is unknown; that is, whether higher educational attainment is the cause of MD, or if MD induces higher educational attainment (although this is highly unlikely). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy to mention that childhood SES is independently associated with MD, regardless of SES in adulthood (i.e., educational attainment).

Several limitations of the current study suggest avenues for future research. First, this study used self-reports of SES in childhood and parental mental illness, rather than a direct assessment of the respondents’ parents. However, previous studies that also used self-reported childhood SES [13] have found similar results [11]. Second, it is possible that we overestimated the association between childhood SES and mental disorders because of common method bias—that is, participants who have stressful memories related to parental SES might have been more likely to report symptoms of mental disorders. Third, although this study was population-based, and weighted analysis was used to adjust for the differences in demographic variables between the respondents and non-respondents, the comparatively small study sample size may not be representative of the whole Japanese population. Further investigation using a larger, nationally representative sample is warranted.

Conclusion

In Japan, childhood SES is likely to be positively associated with the lifetime onset of mental disorders, regardless of family history of mental disorders, childhood physical illness, or SES in adulthood. Further study is needed to replicate these findings and to elucidate other factors, such as parental pressures or social expectations.

References

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M: Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157 (2): 98-112. 10.1093/aje/kwf182.

Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Hu C, Iwata N, Karam AN, Kaur J, Kostyuchenko S, Lépine JP, Levinson D, Matschinger H, Mora ME, Browne MO, Posada-Villa J, Viana MC, Williams DR, Kessler RC: Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 2011, 9: 90-10.1186/1741-7015-9-90.

Merikangas KR, Low NC: The epidemiology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004, 6 (6): 411-421. 10.1007/s11920-004-0004-1.

Lynch J, Kaplan G: Socioeconomic position. Social epidemiology. Edited by: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. 2000, New York: Oxford university press, 13-35.

Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R: Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: a systematic review of the evidence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003, 38 (5): 229-237. 10.1007/s00127-003-0627-2.

Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, Schwartz S, Naveh G, Link BG, Skodol AE, Stueve A: Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992, 255 (5047): 946-952. 10.1126/science.1546291.

Kawakami N, Abdulghani EA, Alonso J, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Fayyad J, Ferry F, Florescu S, Gureje O, Hu C, Lakoma MD, Leblanc W, Lee S, Levinson D, Malhotra S, Matschinger H, Medina-Mora ME, Nakamura Y, Oakley Browne MA, Okoliyski M, Posada-Villa J, Sampson NA, Viana MC, Kessler RC: Early-Life Mental Disorders and Adult Household Income in the World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2012, 72 (3): 228-237. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.009.

Power C, Manor O: Explaining social class differences in psychological health among young adults: a longitudinal perspective. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992, 27 (6): 284-291.

Lundberg O: The impact of childhood living conditions on illness and mortality in adulthood. Soc Sci Med. 1993, 36 (8): 1047-1052. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90122-K.

Fan AP, Eaton WW: Longitudinal study assessing the joint effects of socio-economic status and birth risks on adult emotional and nervous conditions. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001, 40: s78-s83.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL: Socioeconomic status in childhood and the lifetime risk of major depression. Int J Epidemiol. 2002, 31 (2): 359-367. 10.1093/ije/31.2.359.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka L: Socio-economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychol Med. 2003, 33 (8): 1341-1355. 10.1017/S0033291703008377.

McLaughlin KA, Breslau J, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC: Childhood socio-economic status and the onset, persistence, and severity of DSM-IV mental disorders in a US national sample. Soc Sci Med. 2011, 73 (7): 1088-1096. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.011.

Harper S, Lynch J, Hsu WL, Everson SA, Hillemeier MM, Raghunathan TE, Salonen JT, Kaplan GA: Life course socioeconomic conditions and adult psychosocial functioning. Int J Epidemiol. 2002, 31 (2): 395-403. 10.1093/ije/31.2.395.

Quesnel-Vallee A, Taylor M: Socioeconomic pathways to depressive symptoms in adulthood: evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979. Soc Sci Med. 2012, 74 (5): 734-743. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.038.

Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, Gove WR, Evenson RJ, Sloan M: Depression in the United States and Japan: gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (11): 2280-2292. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014.

Nishimura J: Socioeconomic status and depression across Japan, Korea, and China: exploring the impact of labor market structures. Soc Sci Med. 2011, 73 (4): 604-614. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.020.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005, 62 (6): 593-602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, Nakane H, Iwata N, Furukawa TA, Kikkawa T: Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: preliminary finding from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005, 59 (4): 441-452. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01397.x.

Orui M, Kawakami N, Iwata N, Takeshima T, Fukao A: Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and its relationship to suicidal ideation in a Japanese rural community with high suicide and alcohol consumption rates. Environ Health Prev Med. 2011, 16 (6): 384-389. 10.1007/s12199-011-0209-y.

Hirokawa S, Kawakami N, Matsumoto T, Inagaki A, Eguchi N, Tsuchiya M, Katsumata Y, Akazawa M, Kameyama A, Tachimori H, Takeshima T: Mental disorders and suicide in Japan: a nation-wide psychological autopsy case–control study. J Affect Disord. 2012, 140 (2): 168-175. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.001.

Kayano H, Koba S, Matsui T, Fukuoka H, Toshida T, Sakai T, Akutsu Y, Tanno K, Geshi E, Kobayashi Y: Anxiety disorder is associated with nocturnal and early morning hypertension with or without morning surge: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Circ J. 2012, 76 (7): 1670-1677. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1085.

Ohira T: Psychological distress and cardiovascular disease: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Epidemiol. 2010, 20 (3): 185-191. 10.2188/jea.JE20100011.

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, et al: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2197-2223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4.

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C: Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003, 57 (10): 778-783. 10.1136/jech.57.10.778.

Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE: Low Socioeconomic Status and Mental Disorders: a Longitudinal Study of Selection and Causation during Young Adulthood. Am J Sociol. 1999, 104 (4): 1096-1131. 10.1086/210137.

Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004, 13 (2): 93-121. 10.1002/mpr.168.

Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, Nakane H, Iwata N, Furukawa TA, Kikkawa T: Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: the World Mental Health Japan 2002–2004 Survey. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Edited by: Kessler RC, Ustun TB. 2008, New York (NY): Cambridge University Press, 474-485.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004, 291 (21): 2581-2590.

Simon GE, VonKorff M: Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: implications for epidemiologic research. Epidemiol Rev. 1995, 17 (1): 221-227.

Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC: Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999, 8 (1): 39-48. 10.1002/mpr.55.

Abe A: Empirical study of relative deprivation index and poverty in Japan (in Japanese). IPSS Discussion Paper Series. 2005, Tokyo: National Instutite of Population and Social Security Research

Kondo N, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Takeda Y, Yamagata Z: Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health?: Relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 67 (6): 982-987. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.002.

Singer JD, Willett JB: It’s about time: Using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. J Educ Stat. 1993, 18 (2): 155-195. 10.2307/1165085.

Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, Bijl RV, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W, Dragomirecka E, Kohn R, Keller M, Kessler RC, Kawakami N, Kiliç C, Offord D, Ustun TB, Wittchen HU: The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003, 12 (1): 3-21. 10.1002/mpr.138.

Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M: Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Dev. 1999, 70 (4): 1030-1044. 10.1111/1467-8624.00075.

Phinney JS, Ong A, Madden T: Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Dev. 2000, 71 (2): 528-539. 10.1111/1467-8624.00162.

Santos RA: Filipino American children. 1997, New York: Wiley

Oishi S, Sullivan HW: The mediating role of parental expectations in culture and well-being. J Pers. 2005, 73 (5): 1267-1294. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00349.x.

Chao R, Tseng V: Parenting of asians. Handbook of Parenting, Volume 4 Social Conditions and Applied Parenting. Edited by: Bornstein MH. 2002, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 59-93.

Sato T, Sakado K, Uehara T, Nishioka K, Kasahara Y: Perceived parental styles in a Japanese sample of depressive disorders - A replication outside Western culture. Br J Psychiatry. 1997, 170: 173-175. 10.1192/bjp.170.2.173.

Nishikawa S, Sundbom E, Hagglof B: Influence of Perceived Parental Rearing on Adolescent Self-Concept and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in Japan. J Child Fam Stud. 2010, 19 (1): 57-66. 10.1007/s10826-009-9281-y.

Nolen-Hoeksema S: Gender differences in depression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001, 10 (5): 173-176. 10.1111/1467-8721.00142.

Horwitz AV: Outcomes in the sociology of mental health and illness: where have we been and where are we going?. J Health Soc Behav. 2002, 43 (2): 143-151. 10.2307/3090193.

Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C: The development of psychopathology in females and males: current progress and future challenges. Dev Psychopathol. 2003, 15 (3): 719-742.

Zahn-Waxler C: The development of empathy, guilt, and internalization of distress: implications for gender differences in internalizing and externalizing problems. Anxiety, depression, and emotion. Edited by: Davidson RJ. 2000, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 222-265.

Goyette KA: College for some to college for all: Social background, occupational expectations, and educational expectations over time. Soc Sci Res. 2008, 37 (2): 461-484. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.02.002.

Mello ZR: Racial/ethnic group and socioeconomic status variation in educational and occupational expectations from adolescence to adulthood. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009, 30 (4): 494-504. 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.029.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/359/prepub

Acknowledgments

The WMHJ Survey is supported by a Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Furthermore, the WMHJ activities were also supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Further, this study is partially supported by a Grant from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H24-jisedai-shitei-007). None of the authors have any actual or potential conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by the staff members and other field coordinators involved with the WMHJ 2002–2004 Survey. This survey was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Our deepest thanks to the staff for their helpful assistance.

We would also like to thank Dr. Julian Tang of the National Center of Child Health and Development for proofreading and editing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

MO was involved in the literature review and the drafting of the manuscript. TF conceived the study hypothesis, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft, and. RM helped to performed the statistical analyses and draft the manuscript. NK critically evaluated and revised the manuscript to ensure the inclusion of important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ochi, M., Fujiwara, T., Mizuki, R. et al. Association of socioeconomic status in childhood with major depression and generalized anxiety disorder: results from the World Mental Health Japan survey 2002–2006. BMC Public Health 14, 359 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-359

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-359