Abstract

Background

Family planning programs have recently undergone a fundamental shift from being focused on women only to focusing on men individually, or on both partners. However, contraceptive use among married men has remained low in most high-fertility countries including Uganda. Men’s role in reproductive decision-making remains an important and neglected part of understanding fertility control both in high-income and low-income countries. This study examines whether discussion of family planning with a health worker is a critical determinant of modern contraceptive use by sexually active men, and men’s reporting of partner contraceptive use.

Methods

The study used data from the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey comprising 2,295 men aged 15–54 years. Specifically, analyses are based on 1755 men who were sexually active 12 months prior to the study. Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s chi-square test, and logistic regression were used to identify factors that influenced modern contraceptive use among sexually active men in Uganda.

Results

Findings indicated that discussion of family planning with a health worker (OR =1.85; 95% CI: 1.29–2.66), region (OR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.21–0.77), education (OR =2.13; 95% CI: 1.01–4.47), wealth index: richer (OR = 2.52; 95% CI: 1.58–4.01), richest (OR = 2.47; 95% CI: 1.44–4.22), surviving children (OR = 2.04; 95% CI:1.16–3.59) and fertility preference (OR = 3.50; 95% CI: 1.28–9.61) were most significantly associated with modern contraceptive use among men.

Conclusions

The centrality of the role of discussion with health workers in predicting men’s participation in family planning matters may necessitate creation of opportunities for their further engagement at health facilities as well as community levels. Men’s discussion of family planning with health workers was significantly associated with modern contraceptive use. Thus, creating opportunities through which men interact with health workers, for instance during consultations, may improve contraceptive use among couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Like many sub-Saharan countries, Uganda still grapples with a low contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) (30%) and a high fertility rate (TFR) (6.2), the latter having stalled for the last three decades [1]. This has contributed significantly to a high population growth rate of over 3.2% that puts pressure on already meager resources and poses a serious challenge to service provision. Specific and well elaborated strategies to improve reproductive health and address the population challenge are required [2]. Family planning (FP) services have been promoted as critical in giving couples the freedom to space and plan the number of children they wish, but also contributing to the health and overall quality of life of the population [3].

Men, particularly in patriarchal contexts, play a central role in influencing fertility decisions [4, 5]. However, male involvement in family planning remains limited despite the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, which emphasized the need for men’s involvement in sexual and reproductive health issues [6, 7]. Likewise, research investigating factors associated with couples’ contraceptive use has neglected men’s central role [8–10], which has ultimately resulted in reinforcing the idea of family planning as women’s responsibility, leaving little or no role for men [11–13].

It has been observed [14–16] that men, particularly in agrarian subsistence economies, prefer large numbers of children both as a source of labor and economic gain, and as a source of prestige. Given men’s role as decision makers, such perceptions are believed to deter men’s and couples’ utilization of contraceptives [16, 17]. A husband’s approval of the use of contraception is crucial for successful family planning programs [18, 19]. A study in Kenya illustrated that husbands had absolute decision-making power and the ability to effect compliance or submission from their wives [15]. This was also observed in Zimbabwe and Ghana [20, 21].

A challenge confronting the redirection of family planning services toward greater male involvement and couples’ collective decision-making is how to effectively enlist the participation of men [22, 23].

In sub-Saharan Africa, the influence of discussing contraception among couples has been investigated to some extent and has been highlighted as an avenue that triggers and enhances contraceptive use [19, 24, 25]. For instance, among women residing in six countries of sub-Saharan Africa, those who reported frequent communication with their partner about contraception had increased odds of using a family planning method over those who reported never discussing the topic [7].

Provider factors are equally important in influencing contraceptive use. For instance, the facilitation of making informed choices in family planning is associated with better satisfaction and compliance with the method. One consequence is fewer failures [3, 26]. Health care providers are an important source of information about family planning and their opinions about specific methods can also influence couple choices [27]. To promote use of modern contraceptives in formerly pro-natalist countries like Albania, communication campaigns that involved training health care providers were used to assure relevant populations about the safety of modern contraceptives [28].

In other instances, engaging volunteers to use interpersonal communication through household visits and group discussions has been used to disseminate accurate information on family planning methods in countries such as Guinea and Nepal [29, 30].

Whereas health provider factors have the potential to influence contraceptive men. The client– provider interaction provides opportunities use, few studies have examined the factors associated with modern contraceptive use (MCU) among men in the developing world, and particularly discussion of family planning with a health worker. No study has analyzed the role of health workers’ discussion of FP with men in effecting modern contraceptive use among Ugandan for provision of accurate information, allaying fears and misconceptions and, in the case of couples, joint decision-making regarding the different family planning options [8, 27].

Using the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS) dataset, this study examined the influence of discussing family planning with health workers on modern contraceptive use (MCU) among sexually active men, and their reports of partner contraceptive use. We also examined a series of individual level factors including the desire to have other children and the number of children surviving, to measure how these may ultimately influence men’s contraceptive use.

Methods

Data source

This paper is based on the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS) that was conducted in 2011. Authorization to use this data (accessed from the MEASURE DHS website) was obtained upon providing a brief description of our study. Two-stage cluster sampling was used to generate a representative sample of 2,573 men aged 15–54. Informed consent for participation in the study was acquired from the male respondents. The first stage involved selecting the clusters while the second stage selected the households in each cluster. Stratification of urban and rural areas was taken into account. A sample of 404 primary sampling units (PSUs) was covered and proportionally allocated among the ten sub-national regions. Details on the sampling procedure are described elsewhere [1].

Study sample

From a sample of 2,573 men, 1,755 men aged 15–54 who were sexually active in the last 12 months were extracted for further analyses.

Variables

In the DHS men’s questionnaire, respondents were asked if they or their partner’s had used any method to avoid or prevent a pregnancy the last time they had sex, and the method used (see Additional file 1). The coding categories for current contraceptive method use included: not using, pills, intra-uterine device (IUD), injections, condoms, female sterilization, periodic abstinence, withdrawal, implants/Norplant, lactational amenorrhea (LAM), female condoms, foam or jelly [1].

From these categories, modern contraceptive methods included male methods (male condoms and male sterilization) and female methods (pills, female condoms, injections, the IUD, female sterilization and foam or jelly [31].

We generated a dependent variable (MCU) and coded it as a binary outcome: 1 for men’s reported use of contraception and men's reportage of their partner’s use of contraception, and 0 for nonuse of the same. It is possible that some women use contraceptives without their husband’s knowledge. However, in this context men/husbands were aware and reported their partner/wives’ contraceptive use, suggestive of partnership in contraceptive use.

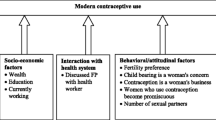

The independent variables in the study were: age, marital status, residence, region, education level, wealth index and employment status. Intermediate variables included: respondents’ interaction with a health worker, number of living children (children surviving) and fertility preference. In addition attitudinal statements were included in the analyses. These were “women who use contraception become promiscuous” and “contraception is a woman’s business”. Whether participants had consulted with a health worker was obtained from the question “In the last few months, have you discussed family planning with a health worker or health professional?”

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted at three levels. First, descriptive statistics were performed for both modern contraceptive use and men’s demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Second, cross tabulations with χ2 tests were run to determine the association between modern contraceptive use and men’s sociodemographics. The variables that were significant at 95% were included in the logistic regression models.

Third, binary logistic regression models were fit to predict modern contraceptive use while controlling for independent variables at different stages. Regression diagnostics were performed by testing for the models’ goodness-of-fit and link tests commands in Stata 12.1 (College Station, Tx, USA) [32]. All the analyses were weighted using the svy command in Stata to control for the differences in sampling probabilities [33].

Results

Descriptive statistics of the respondents

Results presented in Table 1 show that the majority (85%) of the respondents were age 35 and under. About eight in ten respondents (79%) resided in rural areas and few (14%) were from the western region. Seven out of ten (76%) respondents were currently in union. More than half (60%) of the respondents had attained primary education by the time of the survey. Almost all (96%) of the men were currently working in the 12 months preceding the survey.

Four in every ten men (41%) had one to four surviving children and almost half the respondents (47%) wished to have another child. Most (82%) of the men disagreed with the statement that “contraception is a woman’s business”. More than half (60%) disagreed with the statement that “women who used contraceptives become promiscuous”. Few men (14%) had discussed family planning with a health worker. A third (33%) of the men reported that they or their partners were using modern contraceptives to prevent pregnancy.

Table 2 shows Pearson’s chi-square tests of the association between modern contraceptive use and men’s sociodemographic factors. Age, residence, region, marital status, education level attained, working status, number of children surviving, and fertility preference were significantly associated with modern contraceptive use (p < 0.001).

Multivariate results

Results of the logistic regression of MCU and selected background factors are presented in Table 3. Three models are presented: Model 1 (included discussion of family planning with health worker); Model 2 (adjusted for demographic factors); and Model 3 (adjusted for sociodemographics).

Discussing family planning with a health worker was significantly associated with use of modern contraceptives (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 1.19–2.26) in the unadjusted analyses as presented in Model 1. The relationship persisted (OR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.29–2.66) even after adjusting for behavioral, demographic and socioeconomic variables in Model 3.

Subsequent to adjusting for possible confounding, region (southwest), education level (secondary or higher), wealth quintile (richer and richest), children surviving (1–4) and fertility preferences (no partner) were found to be significantly associated with men’s reported use of contraception and men’s reporting their partner’s use of contraception. Men from the southwest region had a lower likelihood of using or reporting their partners’ use of modern contraceptives (OR =0.41; 95% CI: 0.21–0.77) compared with men in Kampala. In addition, men who had secondary or higher education had increased odds (OR =2.13; 95% CI: 1.01–4.47) of MCU compared with those with no education. Men who belonged to the richer and richest wealth quintile had a higher likelihood of using modern contraceptives (OR =2.52; 95% CI: 1.58–4.01) and (OR =2.47; 95% CI: 1.44–4.22) respectively compared with those in the poorest quintiles. Men who had few children (1–4) had increased odds of using modern contraception or reporting partners’ use of contraception (OR = 2.039; 95% CI: 1.16–3.59) compared with those with no children. Additionally, men who had no partner and were never married had a higher likelihood of using modern contraception or reporting partners’ use of contraception (OR = 3.50; 95% CI: 1.28–9.61) compared with those who wanted to have additional children (see Model 3 in Table 3).

In Model 2, men’s age and residence were significantly associated with use of modern contraceptives. However, after adjusting for confounders (Model 3), these associations became insignificant (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The results presented illuminate the critical role of interpersonal communication, and particularly discussion of FP issues involving men and health workers in effecting behavior change. Male respondents who had discussed family planning with a health worker were more likely to use modern contraceptives than those who had not. Discussion of family planning with health workers improves client’s knowledge of contraception and therefore, contributes to beneficial behavior change. Behavior change models stipulate that knowledge is a primary step toward achieving behavior change [34]. This finding is in keeping with findings from a study conducted in Congo where current use of modern contraception was correlated with having discussed contraception with a health worker [35]. Similar results were also reported in a Tanzanian study where training of service providers, communication, and logistical support influenced MCU [36].

Our study further showed that the number of living children was an important factor influencing the use of modern contraception. The men who had fewer than five children had increased odds of using contraception. This is an important finding because although numerous demographic studies on women have indicated this relationship [37, 38], little is known about child survival status and men’s preference for more children [39].

Socioeconomic status is closely linked with people’s behavior and practices, and contraceptive use in particular. In this paper, men from the southwest region were less likely to use modern contraceptives compared with those from Kampala. Over the past decades in Uganda, the western region has recorded the highest fertility rates [40, 41]. According to JP Ntozi [5], the western region has a pro-natalist culture which discourages contraceptive use until a woman has six to eight live children, including at least two sons. Perhaps this explains why men in this region are less likely to use modern contraception. Some studies have indicated that contraceptive use varies across regions and cultural environment [41, 42].

As observed elsewhere [43–45], this study established that wealth status and education level were key determinants of men’s modern contraceptive use. For instance, the likelihood of contraceptive use was higher among rich men with post primary education compared to those men in lowest wealth quintile with nor formal education.

Our findings show that men without partners or who were sterilized/infertile had higher odds of reporting modern contraceptive use compared with those who wanted more children. The sexually active men who had no partners were also the never married ones. Therefore, they used modern contraceptives as a means of preventing pregnancy in the context of unstable relationships where child bearing is not ideal. In such a context, these men preferred to delay fathering children [46].

Some limitations of the paper are worth highlighting. First, the use of the DHS data poses a challenge to establishing the direction of causality. This is particularly so with regard to discussion of FP with a health worker as a predictor of MCU, given the cross-sectional nature of the survey. The authors assumed that discussing family planning with a health worker prompted contraceptive use but the reverse could also have been true. Using contraception may have prompted discussion of contraception with a health worker. It is also possible that men who wanted to use contraception methods were more likely to talk to a provider. Therefore more provider communication would do not impact the men who do not seek to discuss with providers because they have no interest. There could also have been other factors that may have influenced MCU by the men and their reportage of partners’ use, other than discussion.

Second, there was no provision in the dataset to ascertain the context, content, or depth of the discussions between the health workers and their clients (the men). This information would have further enriched our analyses. However, despite these limitations, the paper provides an interesting contribution to the debate on male involvement in family planning, which has been a neglected issue for some time in the Ugandan context.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the strong association that discussion with a health worker has on the likelihood of men’s use of modern contraception and their of partners’ use of contraception. Fertility preference, number of surviving children, wealth index, level of education and region were also among the sociodemographic predictors of MCU. Health workers should therefore be targeted as focal persons in delivering FP messages to men. FP programs should be designed and tailored to enhance FP among men with more than four children and those with low socioeconomic status i.e. the poor and those with low levels of education.

Abbreviations

- FP:

-

Family planning

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health survey

- MCU:

-

Modern contraceptive use

- UDHS:

-

Uganda demographic and health survey

- UBOS:

-

Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

References

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc: Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012, Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc.: Uganda Bureau of Statistics & Macro International

UNFPA: State of the World Population 2012; By Choice not by Chance, Family Planning, Human Rights and Development. 2012, New York: United Nations Population Fund

Frost JJSS, Finer LB: Factors associated with contraceptive use and nonuse in United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004, 39: 90-99.

Caldwell JC, Caldwell P: The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Popul Dev Rev. 1987, 13 (3): 409-437. 10.2307/1973133.

Ntozi JP: High Fertility in Rural Uganda; The Role of Socioeconomic and Biological Factors. 1995, Kampala: Fountain Publishers Ltd.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Programming for Male Involvement in Reproductive Health: Report of the Meeting of WHO Regional Advisers in Reproductive Health. Geneva. World Health Organization and PAHO. 2002, Geneva: World Health Organization

Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N: Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007, 97 (7): 1-7.

Ditekemena J, Koole O, Engmann C, Matendo R, Tshefu A, Ryder R, Colebunders R: Determinants of male involvement in maternal and child health services in sub- Saharan Africa: a review. Reprod Health. 2012, 9 (1): 32-10.1186/1742-4755-9-32.

Kaida A, Kipp W, Hessel P, Konde-Lule J: Male participation in family planning: results from a qualitative study in Mpigi District, Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 2005, 37: 269-286.

Streefland P, Vassall A, Bagdadi S, Bashour H, Zaher H, Maaren P, Kamminga E, Wegelin-Schuringa M, van Liere M, Murphy C: Programming for male involvement in reproductive health. Report of the meeting of WHO Regional Advisors in Reproductive Health WHO/PAHO Washington DC USA 5–7 September 2001. Vaccine. 2013, 21 (12): 1304-1309.

Wortham RA: Spatial differences in fertility decline in Kenya: evidence from recent fertility surveys. Soc Sci J. 2002, 39 (2): 265-276. 10.1016/S0362-3319(02)00167-2.

Mahmood N, Ringheim K: Factors affecting contraceptive use in Pakistan. Pakistan Dev Rev. 1996, 35 (1): 1-22.

Magadi MA, Curtis SL: Trends and determinants of contraceptive method choice in Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2003, 34 (3): 149-159. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00149.x.

Bankole A, Singh S: Couples’ fertility and contraceptive decision-making in developing countries: hearing the man's voice. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 1998, 24 (1): 15-24. 10.2307/2991915.

Blacker J, Opiyo C, Jasseh M, Sloggett A, Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba J: Fertility in Kenya and Uganda: a comparative study of trends and determinants. Popul Stud. 2005, 59 (3): 355-373. 10.1080/00324720500281672.

Caldwell C: High fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Am. 1990, 262 (5): 118-10.1038/scientificamerican0590-118.

Ntozi JPM: High Fertility in Rural Uganda; Role of Socioeconomic and Biological Factors. 1995, Fountain Publishers ltd

Babalola S, Folda L, Babayaro H: The effects of a communication program on contraceptive ideation and use among young women in Northern Nigeria. Stud Fam Plann. 2008, 39 (3): 211-220. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.168.x.

Bawah AA: Spousal communication and family planning behavior in Navrongo: a longitudinal assessment. Stud Fam Plann. 2002, 33 (2): 185-194. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00185.x.

Adamchak MTMDJ: Family planning knowledge, attitudes and practices of men in Zimbabwe. Stud Fam Plann. 1991, 22: 31-38. 10.2307/1966517.

Bawah AA, Akweongo P, Simmons R, Phillips JF: Women’s fears and men’s anxieties: the impact of family planning on gender relations in northern Ghana. Stud Fam Plann. 1999, 30 (1): 54-66. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00054.x.

Campbell M, Sahin-Hodoglugil NN, Potts M: Barriers to fertility regulation: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2006, 37 (2): 87-98. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00088.x.

Mason K, Smith H: Husbands’ versus wives’ fertility goals and use of contraception: the influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography. 2000, 37 (3): 299-311. 10.2307/2648043.

Becker S, Costenbader E: Husbands’ and wives’ reports of contraceptive use. Stud Fam Plann. 2001, 32 (2): 111-129. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00111.x.

Shattuck D, Kerner B, Gilles K, Hartmann M, Ng’ombe T, Guest G: Encouraging contraceptive uptake by motivating men to communicate about family planning: the Malawi male motivator project. Am J Public Health. 2011, 101 (6): 1089-10.2105/AJPH.2010.300091.

Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E: Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10 (1): 530-10.1186/1471-2458-10-530.

Dehlendorf CLK, Ruskin R, Steinauer J: Health care providers’knowledge about contraceptive evidence: a barrier to quality family planning care?. Contraception. 2010, 81: 292-298. 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.11.006.

John Snow Inc with Manoff Group: Strategic Framework. Albania Family Planning Project 2004–2006. 2005, Tirana: John Snow Inc with Manoff Group

Sharan MVT: Spousal communication and family planning adoption: effects of a radio drama serial in Nepal. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 2002, 16-25.

Blake M, Babalola S: Impact of a Male Motivation Campaign on Family Planning Ideation and Practice in Guinea. Field Report No 13. 2002, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs

WHO: Family Planning Fact sheet No. 351. 2012, Geneva: WHO media center, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/,

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Goodness-of-fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods, Part A9. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods. 1980, 1043-1069. http://ibmr.osu.edu/researchers/slemeshow/,

StatCorp: Stata: Release 12. Statistical Software. 2011, College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, http://www.agecon.ksu.edu/support/Stata11Manual/d.pdf,

Catania JA, Kegeles S, Coates TJ: Towards an understanding of risk behavior: an AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM). Health Educ Q. 1990, 17: 53-72. 10.1177/109019819001700107.

Kayembe PK, Fatuma AB, Mapatano MA, Mambu T: Prevalence and determinants of the use of modern contraceptive methods in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Contraception. 2006, 74 (5): 400-406. 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.06.006.

Jooste K, Amukugo HJ: Male involvement in reproductive health: a management perspective. J Nurs Manag. 2012, 7 (10): 1365-2834.

Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE: Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies. Epidemiol Rev. 2010, 32 (1): 152-10.1093/epirev/mxq012.

Sadat-Hashemi Seyed M, Ghorbani R, Majdabadi Hesamodin A, Farahani Farideh K: Factors associated with contraceptive use in Tehran, Iran. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2007, 12 (2): 148-153. 10.1080/13625180601143462.

Tuloro T, Deressa W, Ali A, Davey G: The role of men in contraceptive use and fertility preference in Hossana Town, southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2009, 20 (3): 1043-1069. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/46826/33220,

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS): 2002 Uganda Population and Housing Census "Population Size and Distribution" vol. 3. 2002, Kampala-Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics, http://www.ubos.org/onlinefiles/uploads/ubos/pdf%20documents/2002%20CensusPopnSizeGrowthAnalyticalReport.pdf,

UBOS & Macro Inter: Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. 2007, Claverton Uganda Bureau of Statistics & Macro International

Giusti C, Vignoli D: Determinants of contraceptive use in Egypt: a multilevel approach. Stat Meth Appl. 2006, 15 (1): 89-106. 10.1007/s10260-006-0010-z.

Hinde A, Mturi JA: Recent trends in Tanzanian fertility. Popul Stud. 2000, 54 (2): 177-191. 10.1080/713779080.

Koc J: Determinants of contraceptive use and method choice in Turkey. J Biosoc Sci. 2000, 32: 329-342. 10.1017/S0021932000003291.

Albania DHS: Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. 2010, Albania Institute of Statistics, Institute of Public Health and ICF Macro

Fuse K: Variations in attitudinal gender preferences for children across 50 less- developed countries. J Demogr Res. 2010, 23 (36): 1031-1048.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/286/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the College of Business and Management Sciences-Makerere University for support toward this study. We are also grateful to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and Macro International for providing the dataset. The authors acknowledge support to AK by Training Health Researchers into Vocational Excellence in East Africa (THRiVE), grant number 087540 funded by the Wellcome Trust. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting offices. We are also grateful to THRiVE for supporting the editorial costs of this study. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Edanz in editing the final version of the manuscript. We are also indebted to Dr. Alice Reid and Dr. Larissa Jennings for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AK conceived the study, participated in data analyses, scientific content, interpretation of findings, discussion, conclusions and writing the manuscript. PN conceived the study, participated in background write up, interpretation and in manuscript write up. SOW participated in data analysis and review of manuscript, and BK participated in manuscript review, discussion and interpretation of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Allen Kabagenyi, Patricia Ndugga contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kabagenyi, A., Ndugga, P., Wandera, S.O. et al. Modern contraceptive use among sexually active men in Uganda: does discussion with a health worker matter?. BMC Public Health 14, 286 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-286

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-286