Abstract

Background

Although evidence suggests that poor sleep is associated with chronic disease, little research has been conducted to assess the relationships between insufficient sleep, frequent mental distress (FMD ≥14 days during the past 30 days), obesity, and chronic disease including diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, asthma, and arthritis.

Methods

Data from 375,653 US adults aged ≥ 18 years in the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System were used to assess the relationships between insufficient sleep and chronic disease. The relationships were further examined using a multivariate logistic regression model after controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and potential mediators (FMD and obesity).

Results

The overall prevalence of insufficient sleep during the past 30 days was 10.4% for all 30 days, 17.0% for 14–29 days, 42.0% for 1–13 days, and 30.6% for zero day. The positive relationships between insufficient sleep and each of the six chronic disease were significant (p < 0.0001) after adjustment for covariates and were modestly attenuated but not fully explained by FMD. The relationships between insufficient sleep and both diabetes and high blood pressure were also modestly attenuated but not fully explained by obesity.

Conclusions

Assessment of sleep quantity and quality and additional efforts to encourage optimal sleep and sleep health should be considered in routine medical examinations. Ongoing research designed to test treatments for obesity, mental distress, or various chronic diseases should also consider assessing the impact of these treatments on sleep health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although sleep is a necessity, about 60 million Americans are affected by chronic sleep disorders and sleep problems that can impair physical well-being and cognitive functioning [1]. A growing body of evidence strongly suggests that self-reported sleep durations are correlates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, depression and anxiety [2]. These include a cross-sectional study [3], prospective cohort studies [4–6], and an intervention study [7]. However, underlying mechanisms of this relationship are still widely discussed.

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expanded the information collected on sleep health in the U.S. national surveillance systems based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine [1]. Thus, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the largest telephone health survey in the world, began collecting data on perceived insufficient sleep, defined by the number of days the respondent felt that he/she did not get enough rest or sleep during the past 30 days [8]. Although polysomnography in a sleep clinic provides a more objective measure of sleep loss and sleep quality than a subjective measure of insufficient sleep, it is not feasible for large national surveillance systems. Furthermore, perceived insufficient sleep is similar to a sleep complaint measure provided in a primary care setting to indicate a concern or problem with sleep quality and quantity such as sleep disturbance and other symptoms of sleep disorders. Several reports on insufficient sleep in BRFSS to date have addressed the prevalence of insufficient sleep [9] and the association between perceived insufficient rest/sleep and cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity [10–12] and smoking habits [13]. In contrast to self-reported sleep duration, insufficient sleep is a less studied dimension of sleep experience which may provide additional important information for understanding the role of sleep in general health at the population level. As depression and obesity are associated with impaired sleep [10, 14–16] and several health outcomes [17–22], the present study aims to examine the relationships between perceived insufficient sleep and other chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, arthritis, and asthma, and to assess whether the relationships between perceived insufficient sleep and chronic disease may be attenuated by frequent mental distress (FMD) and obesity.

Methods

Survey design

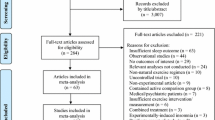

The BRFSS is a large annual, random-digital-dialed telephone survey conducted in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and US territories. The BRFSS collects data on health-related behaviors that are linked to chronic disease and other conditions among the non-institutionalized US civilian population (aged ≥18 years) living in households with landline telephones. Trained interviewers administer standardized questionnaires to all survey participants. Although the response rate in the 2009 BRFSS varied among states (ranged from 37.9% to 66.9%, median = 52.5%) [23], BRFSS data have been verified as being of high quality and very reliable [24]. A study also indicated that bias was not associated with response rate in the BRFSS survey due to the study design [25]. Of 424,592 adults in the 50 states and the District of Columbia who responded to the 2009 BRFSS survey, 375,653 (88.5%) respondents were included in our analysis after we excluded pregnant women (n = 2,358), persons who reported missing value on days of insufficient sleep (n = 7,336), any of six chronic diseases (n = 10,347), or other variables of interest (n = 28,898).

A detailed description of the BRFSS survey design, data collection, and full-text questionnaires can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss. The BRFSS study has been approved by Human Research Review Boards from state departments of health.

Outcome of interest

The occurrence of six chronic diseases was based on affirmative responses to respondents’ being asked if they had ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease (CHD, a heart attack, angina pectoris, or coronary heart disease), stroke, high blood pressure, asthma, or arthritis. Persons who reported “don’t know/not sure” were defined as not having the condition. Analyses were repeated after those who chose ‘do not know/not sure’ on the six chronic diseases were excluded in order to assess the potential misclassification of these respondents due to a less rigorous classification. No significant difference in the results was observed. Those who reported having borderline diabetes or pre-diabetes or having diabetes only during pregnancy were defined as not having diabetes mellitus. Those who reported having borderline high blood pressure, being pre-hypertensive, or having high blood pressure only during pregnancy were defined as not having high blood pressure.

Exposure variable

Perceived insufficient sleep was assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, for about how many days have you felt you did not get enough rest or sleep?” For these analyses, the number of days of insufficient sleep was categorized as 0 day, 1–13 days, 14–29 days, and 30 days.

Assessment of covariates

The socio-demographic characteristics that were examined as covariates in the association between perceived insufficient sleep and these chronic diseases included sex, age in years (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–64, and ≥65), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic), and education (less than high school graduate, high school diploma or GED recipient, some college, and college graduate). The respondent was defined as having frequent mental distress (FMD) if he/she responded ≥14 days to the following question “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” [26]. Assessment of obesity was based on the body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) calculated from self-reported height in inches and weight in pounds (underweight: BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: BMI = 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight: BMI = 25.0-29.9 kg/m2; obese: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [27].

Statistical analyses

First, we examined the distribution of selected characteristics in the study population and the prevalence of ≥14 days of insufficient sleep by selected characteristics. We also assessed the relationships of FMD and obesity to each of the chronic diseases with multivariate logistic regression analyses. Then separate univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the relationship of days of insufficient sleep with each of the six chronic diseases without and with adjustment for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education. The magnitude and significance of effect was assessed using the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI). We also assessed whether FMD and/or obesity were potential mediators in the relationship between days of insufficient sleep and each chronic disease by measuring the percentage change in effect between a model with and without the specific proposed mediator = [(OR model without the mediator- OR model with the mediator)/ (OR model without the mediator - 1)] * 100 [28, 29]. To be conservative, 20% of the percentage change or more was presented here [29] only if the following three criteria were met for determining mediation: 1) there must be a significant relationship between insufficient sleep and chronic disease; 2) there must be a significant relationship between insufficient sleep and either FMD or obesity; 3) there must be a significant relationship between either FMD or obesity and chronic disease [30].

All analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN to account for the complex sampling design [SUDAAN, version 10.0.1, Research Triangle Institute, NC]. The significance level was denoted at 0.01 due to large sample size.

Results

Of 375,653 adult respondents in the current study population, about half were aged ≥45 years (51.4%) and women (49.7%), 70.8% were non-Hispanic white, and 62.2% had more than a high school diploma (Table 1). Among participants, 65.5% reported no days of mental distress and 10.6% reported having FMD, 27.5% were obese, 8.9% had diabetes, 6.1% had a history of coronary heart disease, 2.5% had stroke, 29.2% had high blood pressure, 13.4% reported a history of asthma, and 25.9% reported arthritis. At least one of the six chronic diseases was reported by 51.7% of survey respondents. Only 30.6% reported no days of insufficient sleep, while 42.0% reported 1–13 days, 17.0% reported 14–29 days, and 10.4% reported every day of insufficient rest or sleep in the past 30 days.

Table 2 reveals the prevalence of ≥14 days of perceived insufficient sleep by selected demographics. Compared to their peers, respondents aged 25–44 years, women, non-Hispanic blacks, and respondents who reported having either FMD or obesity reported a higher percentage of frequent insufficient sleep (p < 0.001). In addition, college graduates were less likely to report frequent insufficient sleep than persons with other levels of education attainment (p < 0.01).

Table 3 demonstrated that there are significant relationships for both FMD and obesity with each of the six chronic disease (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, the regression coefficients for the relationships of FMD were strong especially with CHD, stroke, and arthritis. The regression coefficients for the relationships of obesity with diabetes and high blood pressure were also greater than that with the other chronic diseases.

The prevalence of each of the six chronic diseases and the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for the likelihood of having any of the chronic diseases by the four categories of insufficient sleep were obtained from multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 4). Specifically, significant graded relationships were observed at each sleep level with high blood pressure, arthritis, and asthma. At insufficient sleep levels of both 14–29 days and ≥30 days, the likelihoods of having diabetes, CHD, and stroke was greater compared to persons with zero day. FMD moderately attenuated (at least 20-40%) but did not completely explain the significant relationships of insufficient sleep with the six chronic diseases (Model 2). Additionally, the likelihoods of having diabetes and high blood pressure associated with insufficient sleep were moderately attenuated (20-40%) but were not fully explained by obesity (Model 3).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates two important findings. First, to our knowledge, it is the first report to reveal significant relationships between insufficient sleep and high blood pressure, asthma, and arthritis. In addition, significant relationships between insufficient sleep and obesity, diabetes, CHD, and stroke are consistent with recent reports [11, 12, 31]. Second, these significant associations were still present after adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, FMD, and obesity. FMD and obesity were moderate mediators but did not fully explain the relationships of insufficient sleep to these chronic diseases. Therefore, insufficient sleep appears to be an important correlate of the leading chronic diseases.

In the BRFSS insufficient sleep is a newly developed sleep indicator and is not accompanied by reports of hours of sleep per night in the full study population. As an ad hoc analysis, we analyzed data from 74,944 respondents who had information on both insufficient sleep and sleep duration in 12 states in 2009. Our results indicate that the prevalence of reporting ≥14 days of perceived insufficient sleep was greater among those reporting <7 hours sleep (51.0%) in contrast to those reporting 7–9 hours (12.1%) or ≥10 hours sleep (16.1%) in a 24-hour period. Furthermore, the percentage of those reporting an optimal sleep (7–9 hours) also differed by number of days of perceived insufficient sleep (78.2% of 0 day, 67.4% of 1–13 days, 32.4% of 14–29 days, and 19.7% of all 30 days). These results are consistent with the findings from a previous study in Finland [32] and suggest that insufficient sleep is strongly related to sleep duration but they definitely are not redundant because they share only partially same information. Additionally, insufficient sleep may partly reflect some sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, which is also associated with chronic diseases [33–36] but we could not assess that relationship due to lack of data. Considerable data suggest that chronic sleep loss can result in insulin resistance and changes in appetite-regulating hormones, such as increased ghrelin and decreased leptin. The latter conditions further develop into chronic metabolic impairments such as obesity, and may subsequently lead to the development of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and even mortality [37–39].

Experimental evidence suggested that sleep loss was associated with exacerbation of arthritis through the increase of the sensitivity of pain among persons with rheumatoid arthritis [40, 41]. However, further study is needed to understand the directionality of the association between sleep loss and arthritis. In addition, a few studies indicated that poor sleep may affect lung function or lower the quality of life to exacerbate symptoms of asthma among youth [42, 43] or worsen the bronchoconstriction among persons with nocturnal asthma [44]. The evidence may shed light on the mechanism of sleep loss associated with asthma.

Depression and anxiety often co-exist with sleep loss and many chronic diseases [45, 46]. Consistent with previous data from prospective studies, our study demonstrated a highly significant relationship between insufficient sleep and FMD, an indicator of psychological distress, and between FMD and chronic disease [10, 47]. Furthermore, our results suggested that FMD partially mediated the relationships between frequent insufficient sleep and chronic diseases although prospective studies are needed to clarify the pathway.

We assessed obesity as a potential mediator in the relationship between insufficient sleep and chronic disease because sleep loss is associated with increased risk for obesity and obesity is a robust risk factor for diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases [3, 6, 11]. Our findings that obesity might partially mediate the relationships between frequent insufficient sleep and diabetes and high blood pressure were consistent with the results of studies assessing sleep duration [3, 4].

Strengths of this study include the large sample size in this population-based study (N = 375,653). Furthermore, this study represents the adult population in each of the 50 states. However, our study is subject to several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is not possible to confirm whether there is a causal relationship between insufficient sleep and chronic disease. Nevertheless, such a causal link is biologically plausible because sleep loss may lead to metabolic abnormalities and weight gain through the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [47, 48]. In addition, it is also very difficult to determine whether FMD and chronic conditions result in insufficient sleep or whether the direction of effect is reversed. Second, perceived insufficient sleep is a subjective measure of sleep health and has not been validated with polysomnography or other objective measures of sleep loss. Therefore, our results may have bias due to the misclassifications of exposure variable. Third, a significantly higher percentage of short sleep duration (average ≤6 hours per 24–hour period) was recently reported among workers with regular night shifts than among those with regular daytime shifts [49] supporting the role of circadian rhythm disruption in short sleeper and the possible association with chronic diseases [1]. Therefore, shift work status may affect our results. However, we are unable to assess the effect of shift work status or circadian rhythm disruption on the relationship of chronic disease with insufficient sleep due to lack of data in BRFSS. Fourth, although we excluded those respondents who had missing values from the analyses, this is likely to bias our results toward the null if those non-respondents were included in our analyses [28]. The results from a repeated analysis also confirm this assumption after including those non-respondents (data not shown). Additionally, self-reports may lead to underreporting of chronic diseases and obesity [50, 51], which could result in a much stronger relationship of insufficient sleep with the outcomes in this study. Finally, sample selection bias due to the low response rate is also possible because persons with severely impaired physical or mental health might not complete the BRFSS. Institutionalized persons and persons residing in households without landline telephones were also not included in the survey. However, the effect of potential systematic bias might be limited as a significant relationship between insufficient sleep and chronic disease revealed in our study was consistent with the results from prior research measuring sleep duration [2–6].

Conclusions

A positive relationship was observed between frequent insufficient sleep and six chronic diseases. These significant relationships were moderately attenuated by FMD and by obesity. Poor sleep can usually be ameliorated by improved sleep habits, weight loss, continuous positive airway pressure, oral devices, oral-nasal surgery, or pharmacological interventions [52, 53]. Therefore, assessment of sleep quantity and quality and additional efforts to encourage optimal sleep and sleep health should be considered in routine medical examinations. Ongoing research designed to test treatments for obesity, mental distress, or various chronic diseases should also consider assessing the impact of these treatments on sleep health.

Abbreviations

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral risk factor surveillance system

- CDC:

-

Centers for disease control and prevention

- FMD:

-

Frequent mental distress

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index.

References

Institute of Medicine: Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. 2006, Washington DC: National Academies Press

Malhotra A, Loscalzo J: Sleep and cardiovascular disease: an overview. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009, 51: 279-284. 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.004.

Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, Redline S, Baldwin CM, Nieto FJ: Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 863-867. 10.1001/archinte.165.8.863.

Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Malhotra A, Hu FB: A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163: 205-209. 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205.

Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Patel S, Hu FB: A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26: 380-384. 10.2337/diacare.26.2.380.

Gangwisch JE, Steven B, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Rundle AZ, Zammit GK, Malaspina D: Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first national health and nutrition survey. Hypertension. 2006, 47: 833-839. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0.

Haghighatdoost F, Karimi G, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L: Sleep deprivation is associated with lower diet quality indices and higher rate of general and central obesity among young female students in Iran. Nutrition. 2012, 28: 1146-1150. 10.1016/j.nut.2012.04.015.

CDC: Perceived insufficient rest or sleep---four states, 2006. MMWR. 2008, 57: 200-203.

CDC: Perceived insufficient rest or sleep among adults --- United States, 2008. MMWR. 2009, 58: 1175-1179.

Strine TW, Chapman DP: Association of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep Med. 2005, 6: 23-27. 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.06.003.

Shankar A, Syamala S, Kalidindi S: Insufficient rest or sleep and its relation to cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity in a national, multiethnic sample. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e14189-10.1371/journal.pone.0014189.

Vishnu A, Shankar A, Kalidindi S: Examination of the association between insufficient sleep and cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race/ethnicity. Int J Endocrinol. 2011, 2011: 1-8.

Sabanayagam C, Shankar A: The association between active smoking, smokeless tobacco, secondhand smoke exposure and insufficient sleep. Sleep Med. 2011, 12: 7-11. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.002.

Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB: Inadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep. 2005, 28: 1289-1296.

Van den Berg JF, Luijendijk HJ, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Neven AK, Tiemeier H: Sleep in depression and anxiety disorders: a population-based study of elderly persons. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009, 70: 1105-1113. 10.4088/JCP.08m04448.

Van Mill JG, Hoogendijk WJ, Vogelzangs N, van Dyck R, Peninx BW: Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010, 71: 239-246. 10.4088/JCP.09m05218gry.

Davidson K, Jonas BS, Dixon KE, Markovitz JH: Do depression symptoms predict early hypertension incidence in young adults in the CARDIA study/ coronary artery risk development in young adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 1495-1500. 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1495.

Kopec JA, Sayre EC: Traumatic experiences in childhood and the risk of arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Can J Public Health. 2004, 95: 361-365.

Engum A: The role of depression and anxiety in onset of diabetes in a large population-based study. J Psychsom Res. 2007, 62: 31-38. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.009.

Leander M, Cronqvist A, Janson C, Uddenfeldt M, Rask-Andersen A: Health-related quality of life predicts onset of asthma in a longitudinal population study. Resp. Med. 2009, 103: 194-200. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.015.

Shen BJ, Avivi YE, Todaro JF, Spiro A, Laurenceau JP, Ward KD, Niaura R: Anxiety characteristics independently and prospectively predict myocardial infarction in men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 51: 113-119. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.033.

Axon RN, Zhao Y, Egede LE: Association of depressive symptoms with all-cause and ischemic heart disease mortality in adults with self-reported high blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2010, 23: 30-37. 10.1038/ajh.2009.199.

CDC: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, summary data quality report, version 1, revised 04/27/2010, CDC. 2009, ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Data/Brfss/2009_Summary_Data_Quality_Report.pdf. (Accessed May 19, 2010)

Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA: Reliability and validity of measures from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS). Int Public Health. 2001, 46: 1-42.

Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH: Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment: recommendations from the behavioral risk factor surveillance team. MMWR. 2003, 52: 1-12.

Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R: The centers for disease control and prevention’s healthy days measures-population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual life Outcomes. 2003, 1: 37-44. 10.1186/1477-7525-1-37.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel: Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. 1998, Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, NIH publication No. 98–4083

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL: Modern Epidemiology. Measures of effect and measures of association. 2008, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 51-70.

Van de Mheen HD, Stronks K, Mackenbach JP: A lifecourse perspective on socio-economic inequalities in health: The influence of childhood socio-economic conditions as selection process. Sociol Health Illn. 1998, 20: 754-777. 10.1111/1467-9566.00128.

Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986, 51: 1173-1182.

Grandner MA, Patel NP, Perlis ML, Gehrman PR, Xie D, Sha D, Pigeon WR, Teff K, Weaver T, Gooneratne NS: Obesity, diabetes, and exercise associated with sleep-related complaints in the American population. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2011, 19: 463-474. 10.1007/s10389-011-0398-2.

Merikanto I, Kronholm E, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T, Lahti T, Partonen T: Relation of chronotype to sleep complaints in the general Finnish population. Chronobiol Int. 2012, 29: 311-317. 10.3109/07420528.2012.655870.

Lavie P, Here P, Hoffstein V: Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome as a risk factor for high blood pressure. Brit Med J. 2000, 320: 479-482. 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479.

Hung J, Whitford EG, Parsons RW, Hillman DR: Association of sleep apnoea with myocardial infarction in men. Lancet. 1990, 336: 261-264. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91799-G.

Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Javier Nieto F, O’Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE: Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 163: 19-25.

Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V: Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353: 2034-2041. 10.1056/NEJMoa043104.

Spiegel K, Leproult R, Cauter EV: Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1435-1439. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8.

Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, White DP, Schernhammer ES, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB: A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004, 27: 440-444.

Kripke D, Garfinke L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR: Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002, 59: 131-136. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131.

Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P: Induction of neurasthenic musculoskeletal pain syndrome by selective sleep stage deprivation. Psychosom Med. 1976, 38: 35-44.

Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, FitzGerald JD, Ranganath VK, Nicassio PM: Sleep loss exacerbates fatigue, depression, and pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Sleep. 2012, 35: 537-543.

Hanson MD, Chen E, Brief report: The temporal relationships between sleep, cortisol, and lung functioning in youth with asthma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008, 33: 312-316.

Daniel LC, Boergeres J, Kopel SJ, Koinis-Mitchell D: Missed sleep and asthma morbidity in urban children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012, 109: 41-46. 10.1016/j.anai.2012.05.015.

Catterall JR, Rhind GB, Stewart IC, Whyte KF, Shapiro CM, Douglas NJ: Effects of sleep deprivation on overnight bronchoconstriction in nocturnal asthma. Thorax. 1986, 41: 676-680. 10.1136/thx.41.9.676.

Mezick EJ, Hall M, Matthews KA: Are sleep and depression independent or overlapping risk factors for cardiovascular disease?. Sleep Med Rev. 2010, 15: 51-63.

Mallon L, Broman JE, Hetta J: High incidence of diabetes in men with sleep complaints or short sleep duration: a 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged population. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 2762-2767. 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2762.

Hamer M, Molloy GJ, Stamatakis E: Psychological distress as a risk factor for cardiovascular events: pathophysiological and behavioral mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 2156-2162. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.057.

Patel SR, Malhotra A, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Hu FB: Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 164: 846-850.

CDC: Short sleep duration among workers-United States, 2010. MMWR. 2012, 61: 281-288.

Jackson C, Jatulis DE, Fortmann SP: The behavioral risk factor survey and the Stanford five-city project survey: a comparison of cardiovascular risk behavior estimates. Am J Public Health. 1992, 82: 412-416. 10.2105/AJPH.82.3.412.

Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, Jenkins PL, Lewis C, Pearson TA: Validity of cardiovascular disease risk factors assessed by telephone survey: the behavioral risk factor survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993, 46: 561-571. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90129-O.

Taheri S: The link between short sleep duration and obesity: we should recommend more sleep to prevent obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2006, 91: 881-884. 10.1136/adc.2005.093013.

Arora VM, Georgitis , Woodruff JN, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D: Improving sleep hygiene of medical interns: can sleep, alertness, and fatigue education in residency program help?. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167: 1738-1744. 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1738.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/84/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the valuable comments on mediation analysis from Dr. Matthew Zack and efforts from all staff who worked in BRFSS-affiliated organizations at the federal and state levels, and the respondents who provided the survey information in the United States. This paper was presented, in part, at SLEEP 2010, the 24th Annual Meeting of Associated Professional Sleep Societies on June 7, 2010 in San Antonio, Texas.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YL and JBC developed the conceptual model. YL performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript under the supervision of JBC. JBC, AGW, GSP, DPC, THS, LRM, and LP contributed to the interpretation of the results and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yong Liu, Janet B Croft contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Croft, J.B., Wheaton, A.G. et al. Association between perceived insufficient sleep, frequent mental distress, obesity and chronic diseases among US adults, 2009 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. BMC Public Health 13, 84 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-84

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-84