Abstract

Background

Body mass index (BMI) is associated with subjective well-being. Higher BMI is believed to be related with lower well-being. However, the association may not be linear. Therefore, we investigated whether a nonlinear (U-shaped) trend would better describe this relationship, and whether eating disorders might account for the association in young adults.

Methods

FinnTwin16 study evaluated multiple measures of subjective well-being, including life satisfaction, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-20), satisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships, and satisfaction with sex life in young adulthood in the 1975–79 birth cohorts of Finnish twins (n=5240). We studied the relationship between indicators of subjective well-being and BMI both in full birth cohorts and in subgroups stratified by lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders.

Results

We found an inverse U-shaped relationship between all indicators of subjective well-being and BMI in men. There was no overall association between BMI and subjective well-being in women. However, there was an inverse U-shaped relationship between BMI and indicators of subjective well-being in women with a lifetime eating disorder and their healthy female co-twins. Subjective well-being was optimal in the overweight category.

Conclusions

Both underweight and obesity are associated with impaired subjective well-being in young men. The BMI reflecting optimal subjective well-being of young men may be higher than currently recognized. Categorization of body weight in terms of BMI may need to be reassessed in young men. BMI and subjective well-being are related in women with a lifetime eating disorder, but not in the general population of young women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Body mass index (BMI) is associated with both physical and psychological health, including overall mortality, chronic somatic illnesses [1] as well as psychiatric disorders [2, 3]. The relationship with BMI has been found to be U-shaped for mortality [4], depression [5], and quality of life [6–8].

While the link between obesity and impaired quality of life and lowered subjective well-being has been well documented [3, 9–13], less is known about the relationship between subjective well-being and underweight. Low subjective well-being is related to low satisfaction in various life domains and high levels of psychological distress [14]. Low BMI and impaired well-being often coexist in young women [15, 16], and severe underweight in young women is frequently caused by eating disorders. Anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED) affect at least 5.2-6.5% of young females at some point of their life [17–20], but the role of eating disorders in lowered well-being of young adults with extreme BMI remains unknown.

In this study, we studied the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being in a representative population-based sample of young adult twins. Given the high prevalence of eating disorders in this age group, we hypothesized that they could act as an important effect modifier of this relationship. To untangle the effects of eating disorders, we conducted stratified analyses among women with a lifetime eating disorder, their unaffected twin-sisters (representing those with a genetic susceptibility to eating disorders), and women who had neither had an eating disorder nor had a sister with an eating disorder.

Methods

The FinnTwin16 birth cohorts

FinnTwin16 is a nationwide longitudinal cohort study of health behaviors in twins and their families. Virtually all live twin births during 1975–1979 were identified in the central population registry of Finland. The twins were sent self-report questionnaires when they were 16, 17, 18 and 22–28 y, while their parents participated by answering questionnaires about themselves and the twins’ childhood at baseline. In our study we used data from the fourth wave of questionnaires (collected on each birth cohort semi-annually from beginning of 2000 to mid-2002). Data collection and analysis were approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki and the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University, while psychiatric interviews of a subset were approved by the ethical committee of Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. The interviewed subjects provided written informed consent, while the questionnaire study was accompanied with an extensive cover letter giving the purpose of the study and details of data protection. Subjects were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Participants

FinnTwin16 wave 4 consists of self-reported data collected from 2415 males and 2825 females (response rates 78.8% and 90.0%, respectively). The participants were 22–28 years old (mean 24.5, SD 0.94) at the time of the study. The questionnaires assessed various health behaviors and included scales on subjective well-being (described below), as well as a screen on eating disorders, described in detail by Keski-Rahkonen et al. [21].

Exclusion criteria

We excluded subjects with any of the following conditions, which affect both body weight and subjective well-being: self-reported somatic illnesses (240 men, 276 women), pregnancy (118 women), self-reported lifetime psychosis or current antipsychotic medication (8 men, 7 women). It was not possible to control for depressive and anxiety disorder since the indicators used in our study are designed to measure mental distress and mood.

We excluded from analyses a total of 640 participants (248 men and 392 women) based on one or more exclusion criteria listed above. Weight or height values were missing for 16 men and 13 women (0.6% of the total sample). The sample used in the analyses consisted of 2151 men (out of whom 7 men with a lifetime eating disorder) and 2422 women (out of whom 2242 healthy women, 89 women with a lifetime eating disorder, and 32 healthy female co-twins of women with a lifetime eating disorder).

Female subgroups

Healthy women (n=2242) did not report psychopathology related to eating or weight. We invited women who screened positive for eating disorders (N=292) and their screen-negative female co-twins (N=134) to participate in diagnostic telephone interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; [22]) to obtain current and lifetime diagnoses of AN, BN, and BED (definition of BED according to DSM-IV research criteria). The diagnostic interviews are described elsewhere in detail [18, 19, 21]. The interviews identified 109 women with lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders. We excluded 20 of these women from the analyses according to the criteria described above. The final sample consisted of 89 women with eating disorders. We identified 52 female twin pairs discordant for DSM-IV eating disorders in our sample. Healthy co-twins did not report symptoms of eating disorders (n=32).

Indicators of subjective well-being

We chose to assess subjective well-being using the following scales. Of these, GHQ-20 is designed for screening psychological distress in community settings and non-psychiatric clinical settings, such as primary care or general practice [23, 24]. It is vastly studied, and shown to predict psychiatric morbidity. Life satisfaction scale is also a well-established measure. It is shown to correlate strongly with Beck Depression Index [25] and predict i.a. the risk of suicide [26]. In addition, we identified items in the questionnaire that had face validity in assessing subjective well-being; these included satisfaction with specific life domains.

Life satisfaction

Allardt’s four item scale life satisfaction (1973) measures levels of interest, happiness, easiness and loneliness of life [27]. The response alternatives were scored on a scale from 1 to 5, yielding a range of 4–20. Higher scores indicate higher dissatisfaction in life. Reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.71).

GHQ-20

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-20) is a 20-item scale with a sum score range from 20 to 80, higher scores indicating an elevated level of psychological distress. GHQ-20 had excellent reliability in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha 0.91).

Satisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships

In the questionnaire, subjects assessed their satisfaction with leisure time at home, leisure time spent outside home, success at work or studies, and relationship with their co-twin, mother, father, and with their partner. As these items correlated highly, we used their sum score as a single variable in our analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of dissatisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70.

Satisfaction with sex life

In the questionnaire, subjects assessed their satisfaction with sex life using a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher dissatisfaction.

Body Mass Index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated from self-reported height and weight. The correlation of measured and self-reported BMI was 0.89, and the means of self-reported and measured BMI differed by 0.93 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.79–1.07) kg/m2 in a subset of the cohort (n=566) [28]. For descriptive purpose we classified persons with BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 as underweight and those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 as obese. We used sex-specific Z-score of BMI in all analyses.

Covariates

In regression models, educational level, physical activity index, smoking status, total amount of consumed alcohol per month and drinking to intoxication were set as covariates. Educational level was a four-level categorical variable (compulsory school, vocational secondary education, academic secondary education, and tertiary education) [29]. We calculated physical activity index from the product of self-reported exercise intensity, duration (hours) and yearly frequency (days) as described by Mustelin et al. [28]. Smoking status had three categories based on the self-reported frequency of tobacco consumption: non-smoker (combining never and former smoker), light smoker, and heavy smoker (10 or more cigarettes per day). We used self-reported total amount of alcohol consumed during one month’s period and frequency of drinking until intoxication as covariates, as the total amount of consumed alcohol per time unit has been associated with body weight in many but not all studies [30, 31] and drinking to intoxication and alcoholism are associated with psychological health [32].

Statistical analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata 11.0 software. The U-shaped association between BMI and indicators of subjective well-being was studied using linear regression modeling. We fit initially models with both a linear and a quadratic term for BMI. If the quadratic term (BMI-squared) was non-significant, we examined the significance of the linear association. We proceeded with two sets of analyses in two phases, the first set without adjustments and the second set adjusted for the covariates listed above. We used the whole sample to test the association between BMI and subjective well-being in the whole population. Next we applied the same regression models separately for healthy women, women with a lifetime eating disorder and their healthy female co-twins, in order to test the hypothesis that eating disorders or a familial predisposition to such disorders are an effect modifier for the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being. Comparison of the two latter groups indicated whether the association in women with eating disorders was attributable to the disorder or to an underlying familial, possibly genetic susceptibility. All analyses took clustering of twin individuals within pairs into account, as the subjects had been sampled as members of twin pairs [33].

Results

Descriptive statistics

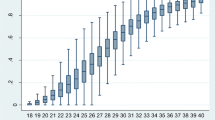

Men had a mean BMI of 23.9 (SD 3.1) kg/m2 and women a mean BMI of 22.2 (3.5) kg/m2 (Table 1). Few men (1.2%) were underweight, while 7% of women were underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2). Obesity was relatively rare among these young adults, as approximately 4% of both men and women were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) (for distribution of BMI see Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Dieting behavior was common: 42.0% of women and 24.4% of men reported intentionally having lost weight more than 5 kg at least once. Current mean BMI was similar in healthy women, in women with a lifetime diagnosis of eating disorder, and in their healthy twin-sisters (Table 1). However, there were considerable differences between the weights of women with different eating disorder diagnoses. Divided by eating disorder diagnosis, the mean BMI was 21.2 (2.4) kg/m2 in the 32 women with AN, 23.6 (4.3) kg/m2 in the 37 women with BN, 20.1 (1.2) kg/m2 in the 9 women with AN and BN, and 26.2 (3.7) kg/m2 in the 11 women with BED (Table 2).

Indicators of subjective well-being

Overall, women reported lower levels of subjective well-being than men (higher scores in life satisfaction, GHQ-20 and satisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships). Lean men tended to experience lower levels of subjective well-being than obese men, yet this could not be attributed to diagnosed eating disorders (five men had lifetime AN and two had lifetime BED). The opposite was seen among women, as obese women experienced lower levels of subjective well-being than lean women. Women with a lifetime eating disorder and their healthy twin-sisters reported lower levels of subjective well-being than other women (Table 1). Subjective well-being tended to be lower among women with eating disorders, with remarkably high distress expressed by women with lifetime diagnoses of both AN and BN (Table 2).

Association of BMI with indicators of subjective well-being

Men

All markers of subjective well-being correlated with BMI in both unadjusted and covariate-adjusted models. The adjusted quadratic regression model showed a U-shaped association curve with life satisfaction (p=0.003) and GHQ-20 (p=0.005), as well as with satisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships (p<0.001) and satisfaction with sex life (p<0.001) (Figure 1). The nadir of the U-shaped regression curve for all indicators of subjective well-being varied from +0.72 to +1.59 Z-score, corresponding to BMI of 26.1 to 28.9 kg/m2. Given the observed quadratic relationships, linear associations were not studied in men.

Women

The analyses were first done for all women and healthy women, both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates.

No statistically significant U-shaped relationships between BMI and subjective well-being were found in the whole group of women or healthy women (Table 3). However, in linear models, there was a trend toward association between BMI and dissatisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships (r=0.088, p=0.059 in the adjusted model). Also, there was a positive linear association between BMI and dissatisfaction with sex life (r=0.057, p= 0.007), which persisted also when the analyses were confined to healthy women (i.e. excluding women with eating disorders and their twin sisters) (r= 0.052, p= 0.016). No other linear associations were found.

Among women with lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders, a U-shaped relationship existed between BMI and life satisfaction (p=0.015), GHQ-20 (p<0.001). Same applied to satisfaction with leisure time, work, and family relationships (p=0.002) (Figure 2). The nadir of these regression curves was in the overweight category, ranging from Z-score +1.22 to +1.96, corresponding to BMI of 26.4 to 29.0 kg/m2. After excluding women with BED, the nadir of the regression curves ranged from +1.43 to +2.15 Z-score (BMI 27.2 to 29.7 kg/m2). Among healthy co-twins of women with a lifetime eating disorder, a U-shaped relationship existed between BMI and life satisfaction (p=0.044) and, respectively, a trend towards relationship between BMI and GHQ-20 (p=0.066) was observed. The nadir points for these regression curves were +0.41 and +0.59 Z-score (BMI 23.6 and 24.3 kg/m2), respectively. Table 3 shows the results of the analyses in all women and across the three studied female subgroups (i.e. healthy women, women with a lifetime eating disorder, and healthy female co-twins).

Discussion

In our study, we found an inverse U-shaped relationship between BMI and subjective well-being in men. This relationship was constant across all indicators of psychological health, with highest levels of subjective well-being in the overweight category (according to World Health Organization classification of BMI, 1995). In women, BMI and subjective well-being were not associated. However, in females current or earlier eating disorder modified this relationship, and a similar effect modification was also seen among healthy twin-sisters of women with a lifetime eating disorder.

Our findings in men support those of previous studies on the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being in males. A positive correlation between obesity and impaired mental health has been identified in many studies [3, 13, 34, 35], while the opposite has been reported in a few studies [36, 37]. The effect of overweight on mental health remains controversial. A study on 43,534 Dutch adults [5] showed a U-shaped curve between depression and BMI, with least depressive symptoms in the overweight category. In the Canadian CaMos study on 9,423 adults, having weight within the overweight category was associated with slightly better health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in men [8]. In our study, estimates of the optimal BMI in terms of subjective well-being in men varied from 26.1 to 28.9 kg/m2.

Having one’s weight in the overweight category might even be beneficial for young men’s psychological health. This is probably in part attributable to the fact that men usually have higher lean body mass compared to women. BMI does not differentiate between fat and muscle tissue, thus BMI in the overweight range does not necessarily imply an excess of fat tissue. The highest levels of physical activity in men were seen at a BMI of 26.5 kg/m2 in this study (Additional file 2: Figure S2). In addition, young males’ body ideal is known to base largely on muscularity, and muscle dissatisfaction in turn is shown to be associated with psychological distress in the same FinnTwin16 cohorts [38] as used in the current study. Another possible explanation may lie in exposure to obesogenic environment; maintaining normal weight in such environment might be more stressful than allowing some weight gain, which in turn would result in optimal well-being in the overweight category in men.

In keeping with our findings, underweight has been related with impaired quality of life in men [39, 40]. Low subjective well-being among men with low BMI in our study could not be attributed to a diagnosed eating disorder, but the effect of subclinical disordered eating and self-reporting bias cannot be excluded.

In studies of BMI and well-being, the authors have reported either an inverse U-shaped relationship [6, 35], or a negative linear relationship [41] in women. While normal weight appeared to be optimal in most studies [6, 35], an Australian study reported significantly lower psychological distress in overweight compared to normal weight female participants [36]. A limitation of these studies is that they did not take into account eating disorders, which affect both psychological well-being and body weight, and contribute to underweight in young adult women. In our study, the group means of most indicators of subjective well-being were highest among women with normal weight and lowest among obese women, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The relationship between BMI and subjective well-being was somewhat different in women with a lifetime eating disorder. The optimal BMI for subjective well-being appeared to be in the overweight range (BMI 26.4 to 29.0 kg/m2), also after excluding women with BED from the analyses. To our knowledge, the relationship of BMI and psychological health has not been studied earlier in women with a lifetime eating disorder. Due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we were unable to determine how the altered relationship between BMI and subjective well-being develops as a function of time after onset or recovery. Interestingly, a similar effect modification was observed also in the twin-sisters of women with a lifetime eating disorder who did not report any psychopathology related to eating or weight. This suggests an underlying familial, possibly genetic susceptibility as an effect modifier of the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being. A previous study suggested shared genetic risk for depression and obesity as an explanatory factor for the association between these two conditions in women [42]. The findings on shared genetic transmission of depression and eating disorders have been ambiguous [43, 44]. Our findings suggest that the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being is greatly attributable to a susceptibility to eating disorders in women. This might imply that body weight plays a greater role in the subjective well-being of these women compared to women without a susceptibility to eating disorders. Another explanation would be that when being exposed to mental distress, these women more readily react by either losing or gaining weight.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to take into account eating disorders as an effect modifier of the relationship between BMI and psychological health. Due to the population-based study design and comprehensive diagnostic procedures to identify eating disorders, the generalizability of our findings to young adults is good. The BMI and morbidity/mortality of adult twins do not differ from the general population [45–48]. Our study was cross-sectional, thus causality cannot be evaluated. BMI was a self-reported measure, yet the agreement between the measured and reported values was good [28]. Some of the instruments used in this study may be too crude to detect differences in the general population. This was most obvious for the measure of satisfaction with sex life, which was unable to detect differences between healthy women and women with a lifetime eating disorder, yet sexual dysfunction is common in women with eating disorders [49].

Conclusions

Our study provides evidence for the inverse U-shaped relationship between BMI and subjective well-being in men. Categorization of body weight in terms of BMI may need to be reassessed in young men. To our knowledge, this is the first study to take into account eating disorders as potential effect modifiers of this relationship in women. Our findings indicate that eating disorders should be taken into consideration in future studies due to the strong inverse U-shaped relationship between BMI and subjective well-being in women with predisposition to such disorders.

Abbreviations

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- BED:

-

Binge-eating disorder

References

Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH: The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1523-1529. 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523.

Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA: Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008, 70: 288-297. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651651.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al: Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010, 67: 220-229. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2.

Childers DK, Allison DB: The ‘obesity paradox’: a parsimonious explanation for relations among obesity, mortality rate and aging?. Int J Obes. 2010, 34: 1231-1238. 10.1038/ijo.2010.71.

de Wit LM, van Straten A, van Herten M, Penninx BW, Cuijpers P: Depression and body mass index, a U-shaped association. BMC Publ Health. 2009, 9: 14-10.1186/1471-2458-9-14.

Ford ES, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Mokdad AH, Chapman DP: Self-reported body mass index and health-related quality of life: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Obes Res. 2001, 9: 21-31. 10.1038/oby.2001.4.

Wee HL, Cheung YB, Loke WC, Tan CB, Chow MH, Li SC, et al: The association of body mass index with health-related quality of life: an exploratory study in a multiethnic Asian population. Value Health. 2008, 11 (Suppl 1): S105-S114.

Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, Barr SI, Gao Y, Prior JC, et al: The association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: data from CaMos, a stratified population study. Qual Life Res. 2007, 16: 1595-1603. 10.1007/s11136-007-9273-6.

Han TS, Tijhuis MA, Lean ME, Seidell JC: Quality of life in relation to overweight and body fat distribution. Am J Public Health. 1998, 88: 1814-1820. 10.2105/AJPH.88.12.1814.

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I: Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev. 2001, 2: 173-182. 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00032.x.

Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M: Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life - a Swedish population study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002, 26: 417-424. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801919.

Lean ME, Han TS, Seidell JC: Impairment of health and quality of life in people with large waist circumference. Lancet. 1998, 351: 853-856. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10004-6.

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P: Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 178: 230-235. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015.

Diener E: Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1984, 95: 542-575.

Ali SM, Lindstrom M: Socioeconomic, psychosocial, behavioural, and psychological determinants of BMI among young women: differing patterns for underweight and overweight/obesity. Eur J Public Health. 2006, 16: 325-331.

McCrea RL, Berger YG, King MB: Body mass index and common mental disorders: exploring the shape of the association and its moderation by age, gender and education. Int J Obes. 2011, 36: 414-421.

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC: The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 61: 348-358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040.

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Susser ES, Linna MS, Sihvola E, Raevuori A, et al: Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry. 2007, 164: 1259-1265. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081388.

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Linna MS, Raevuori A, Sihvola E, Bulik CM, et al: Incidence and outcomes of bulimia nervosa: a nationwide population-based study. Psychol Med. 2009, 39: 823-831. 10.1017/S0033291708003942.

Preti A, Girolamo G, Vilagut G, Alonso J, Graaf R, Bruffaerts R, et al: The epidemiology of eating disorders in six european countries: results of the ESEMeD-WMH project. J Psychiatr Res. 2009, 43: 1125-1132. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.04.003.

Keski-Rahkonen A, Sihvola E, Raevuori A, Kaukoranta J, Bulik CM, Hoek HW, et al: Reliability of self-reported eating disorders: optimizing population screening. Int J Eat Disord. 2006, 39: 754-762. 10.1002/eat.20277.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J: Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP). 2002, New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute

Goldberg DP: The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. 1972, London: Oxford University Press

Penninkilampi-Kerola V, Miettunen J, Ebeling H: A comparative assessment of the factor structures and psychometric properties of the GHQ-12 and the GHQ-20 based on data from a Finnish population-based sample. Scand J Psychol. 2006, 47: 431-440. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00551.x.

Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Kaprio J, Honkanen R, Viinamaki H, Koskenvuo M: Life satisfaction and depression in a 15-year follow-up of healthy adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004, 39: 994-999. 10.1007/s00127-004-0833-6.

Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkanen R, Viinamaki H, Heikkila K, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M: Life satisfaction and suicide: a 20-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 433-439. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.433.

Allardt E: About dimension of welfare: an explanatory analysis of the comparative Scandinavian survey. University of Helsinki research group of comparative sociology research report 1. 1973, Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki

Mustelin L, Silventoinen K, Pietilainen K, Rissanen A, Kaprio J: Physical activity reduces the influence of genetic effects on BMI and waist circumference: a study in young adult twins. Int J Obes. 2009, 33: 29-36. 10.1038/ijo.2008.258.

Latvala A, Dick DM, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Suvisaari J, Viken RJ, Rose RJ, et al: Genetic correlation and gene-environment interaction between alcohol problems and educational level in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011, 72: 210-220.

Lahti-Koski M, Pietinen P, Heliovaara M, Vartiainen E: Associations of body mass index and obesity with physical activity, food choices, alcohol intake, and smoking in the 1982–1997 FINRISK studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 75: 809-817.

Pajari M, Pietilainen KH, Kaprio J, Rose RJ, Saarni SE: The effect of alcohol consumption on later obesity in early adulthood - a population-based longitudinal study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010, 45: 173-179. 10.1093/alcalc/agp090.

Blow FC, Serras AM, Barry KL: Late-life depression and alcoholism. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007, 9: 14-19. 10.1007/s11920-007-0004-z.

Williams RL: A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000, 56: 645-646. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00645.x.

Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Petry NM: Gender differences in associations between body mass index and DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Ann Epidemiol. 2008, 18: 458-466. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.009.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Dhingra S, Li C, Strine TW, Mokdad AH: Depression and anxiety among US adults: associations with body mass index. Int J Obes. 2009, 33: 257-266. 10.1038/ijo.2008.268.

Goldney RD, Dunn KI, Air TM, Dal Grande E, Taylor AW: Relationships between body mass index, mental health, and suicidal ideation: population perspective using two methods. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009, 43: 652-658. 10.1080/00048670902970825.

McLaren L, Beck CA, Patten SB, Fick GH, Adair CE: The relationship between body mass index and mental health. A population-based study of the effects of the definition of mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008, 43: 63-71. 10.1007/s00127-007-0269-x.

Raevuori A, Keski-Rahkonen A, Bulik CM, Rose RJ, Rissanen A, Kaprio J: Muscle dissatisfaction in young adult men. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006, 4 (2): 6-

Wee HL, Wu Y, Thumboo J, Lee J, Tai ES: Association of body mass index with short-form 36 physical and mental component summary scores in a multiethnic Asian population. Int J Obes. 2010, 34: 1034-1043. 10.1038/ijo.2010.24.

Jia H, Lubetkin EI: The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health. 2005, 27: 156-164. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi025.

Bjerkeset O, Romundstad P, Evans J, Gunnell D: Association of adult body mass index and height with anxiety, depression, and suicide in the general population: the HUNT study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008, 167: 193-202.

Afari N, Noonan C, Goldberg J, Roy-Byrne P, Schur E, Golnari G, et al: Depression and obesity: do shared genes explain the relationship?. Depress Anxiety. 2010, 27: 799-806. 10.1002/da.20704.

Lilenfeld LR, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Merikangas KR, Plotnicov K, Pollice C, et al: A controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives and effects of proband comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998, 55: 603-610. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.603.

Wade TD, Bulik CM, Neale M, Kendler KS: Anorexia nervosa and major depression: shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2000, 157: 469-471. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.469.

Rissanen A, Heliovaara M, Aromaa A: Overweight and anthropometric changes in adulthood: a prospective study of 17,000 Finns. Int J Obes. 1988, 12: 391-401.

Chitkara B, Macdonald A, Reveley AM: Twin birth and adult psychiatric disorder. An examination of the case records of the Maudsley Hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1988, 152: 391-398. 10.1192/bjp.152.3.391.

Kendler KS, Martin NG, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: Self-report psychiatric symptoms in twins and their nontwin relatives: are twins different?. Am J Med Genet. 1995, 60: 588-591. 10.1002/ajmg.1320600622.

Kaprio J: The Finnish Twin cohort study: an update. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013, epub ahead of print

Pinheiro AP, Raney TJ, Thornton LM, Fichter MM, Berrettini WH, Goldman D, et al: Sexual functioning in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010, 43: 123-129.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/231/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful for the participants of the FinnTwin16 cohort study. Data collection in the FinnTwin16 study has been supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants AA-12502, AA-00145, and AA-09203 to R J Rose), the Academy of Finland (grants 100499, 205585 and 141054 to JK), and the Academy of Finland Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (grant numbers: 213506, 129680) and grants from the Helsinki University Central Hospital. The current study has been supported by Doctoral Programs in Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Author ML contributed to designing the current study, performed the statistical analysis of the data, and drafted the manuscript. Author JK conceived the FinnTwin16 study, contributed to FinnTwin16 wave 4 questionnaire, contributed to the current study design, data analysis, and interpretation of the data, and participated in drafting the paper. Authors ARa, ES, and AK-R contributed to the diagnostic interviews and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Authors AK-R and ARi contributed to FinnTwin wave 4 questionnaire, and ARi contributed to the current study design and interpretation of the data, and participated in drafting the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2012_5501_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Figure S2: The inverse U-shaped relationship between physical activity index and BMI (p<0.001) in men. (PDF 18 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Linna, M.S., Kaprio, J., Raevuori, A. et al. Body mass index and subjective well-being in young adults: a twin population study. BMC Public Health 13, 231 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-231

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-231