Abstract

Background

Despite Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) being the epicenter of the HIV epidemic, uptake of HIV testing is not optimal. While qualitative studies have been undertaken to investigate factors influencing uptake of HIV testing, systematic reviews to provide a more comprehensive understanding are lacking.

Methods

Using Noblit and Hare’s meta-ethnography method, we synthesised published qualitative research to understand factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in SSA. We identified 5,686 citations out of which 56 were selected for full text review and synthesised 42 papers from 13 countries using Malpass’ notion of first-, second-, and third-order constructs.

Results

The predominant factors enabling uptake of HIV testing are deterioration of physical health and/or death of sexual partner or child. The roll-out of various HIV testing initiatives such as ‘opt-out’ provider-initiated HIV testing and mobile HIV testing has improved uptake of HIV testing by being conveniently available and attenuating fear of HIV-related stigma and financial costs. Other enabling factors are availability of treatment and social network influence and support. Major barriers to uptake of HIV testing comprise perceived low risk of HIV infection, perceived health workers’ inability to maintain confidentiality and fear of HIV-related stigma. While the increasingly wider availability of life-saving treatment in SSA is an incentive to test, the perceived psychological burden of living with HIV inhibits uptake of HIV testing. Other barriers are direct and indirect financial costs of accessing HIV testing, and gender inequality which undermines women’s decision making autonomy about HIV testing. Despite differences across SSA, the findings suggest comparable factors influencing HIV testing.

Conclusions

Improving uptake of HIV testing requires addressing perception of low risk of HIV infection and perceived inability to live with HIV. There is also a need to continue addressing HIV-related stigma, which is intricately linked to individual economic support. Building confidence in the health system through improving delivery of health care and scaling up HIV testing strategies that attenuate social and economic costs of seeking HIV testing could also contribute towards increasing uptake of HIV testing in SSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV continues to be a public health burden in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Out of an estimated 34 million people living with HIV worldwide at the end of 2010, 68% resided in SSA [1] and an estimated 1.9 million people became newly infected in 2010 [2]. Efforts to achieve zero new infections and zero AIDS-related deaths [3] require increased uptake of HIV testing as a gateway to HIV prevention, treatment and care. To address this health problem, coupled with increasingly wider availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART), many countries in SSA have in recent years dramatically scaled up HIV testing services. For instance, health facilities providing HIV testing services in 37 countries of SSA increased by 50% from 11,000 in 2007 to 16,500 in 2008 [4].

Despite the increasingly wider provision of HIV testing services, ten population-based surveys estimate that the median percentage of people living with HIV who know their status is below 40% [5]. Quantitative studies have identified stigma and discrimination [6]; perceived low risk of HIV infection [7]; perceived lack of confidentiality [8]; and distance to testing sites [9] as barriers to uptake of HIV testing. Enabling factors include perceived anonymity of testing [10]; convenience of home-based HIV testing [11]; and availability of ART [12]. Qualitative studies have also been conducted in SSA that additionally highlighted social dynamics influencing uptake of HIV testing. Despite the volume of this evidence and the contribution it can make towards a better understanding of factors influencing uptake of HIV testing in SSA, systematic reviews are lacking.

Methods

We used the meta-ethnographic approach first put forward by Noblit and Hare [13] to synthesise published qualitative research findings. Meta-ethnography has increasingly been used to re-interpret and synthesise qualitative research findings across multiple studies in order to gain in-depth understanding of a phenomena [14–17]. This involves the ‘juxtaposition of studies and the connections between them’ [18] in order to achieve greater conceptual development and insight than would be obtained from individual studies [15]. Emphasis is on developing new interpretations and concepts rather than accumulation of information [19].

Search strategy and identification of papers

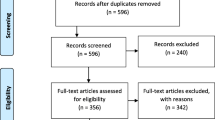

CINAHL, CSA, EMBASE, JSTOR, Medline and Web of Science were searched for published qualitative research findings up to end of February 2012. The first search was done on 30th June 2010 and repeated on 26th February 2011. Repeated searches using the same search strategy were undertaken until end of February 2012 to ensure that no new publications were omitted. The searches yielded 5,686 citations of which 4,466 were subject to title and abstract review. 1,220 were duplicate papers. An over-inclusive search strategy was used to ensure that no papers were missed. The key search words used were: “HIV OR “Acquired Immuno-deficiency Syndrome” OR AIDS OR “HIV infection” or “HIV/AIDS”; VCT OR “voluntary counselling and testing” OR “HIV test”; Africa OR “sub-Saharan Africa” OR SSA. We also reviewed references of the selected papers to ensure that no papers were missed. Two researchers (MM and HN) reviewed titles and abstract in duplicate to exclude ineligible articles. Papers that met the inclusion criteria were subject to full-text review (Figure 1).

Quality assessment and inclusion criteria

Quality appraisal of qualitative research still remains contested [20–23] because ‘there is no unified body of theory, methodology or method that can collectively be described as qualitative research’ [24]. Previous meta-ethnography studies have not used any formal appraisal checklist [17, 20] or did not exclude any paper on the basis of pre-specified quality assessment criteria [22, 25, 26]. Barbour [27] has pointed out that while checklists are useful in improving qualitative research, such ‘technical procedures’ can affect the contributions of systematic qualitative research. With this contestation in mind, but to ensure inclusion of relevant ‘quality’ papers, our inclusion criteria comprised: peer-reviewed publications only; published in English; conducted in SSA; focused on access to HIV testing; and reported qualitative findings - including mixed-methods papers. Forty-two (42) publications from thirteen (13) SSA met the inclusion criteria (Table 1).

Analysis and synthesis process

To establish how the concepts from different papers were related to one another, we created a grid and entered the concepts from each paper (see Table 2). We used Malpass’s notion of first-, second-and third-order constructs to generate the concepts [26]. First-order constructs represent the views of research participants while second order-constructs are authors’ interpretation of research participants’ views [14, 23]. Second-order constructs were identified, cross-compared and used to develop third-order constructs - our interpretations of the researchers’ interpretation of research participants’ views [23, 26].

Using the process of translation – transfer of ideas, concepts and metaphors across different studies [14], we compared the concepts of the papers i.e. paper 1 with paper 2 and the synthesised concepts of the two papers with paper 3 and so on, until all studies had been translated into each other [16, 23]. The translation process was iterative to ensure that third-order constructs reflected concepts of the individual papers. New concepts were also identified through the process. Thus, we were able to re-interpret and re-conceptualise the findings to develop deeper meaning across the individual papers. The third-order constructs were transposed into a conceptual model showing the relationships between the different factors influencing uptake of HIV testing in SSA.

Results

Forty-two (42) peer-reviewed qualitative and mixed-method papers published between 2001 and 2012 from thirteen (13) SSA countries were included in the synthesis (see Table 1). Thirty (30) were exclusively qualitative studies and twelve (12) were mixed-methods papers. While SSA is not a heterogeneous setting, some common characteristics could be deciphered: generalised HIV epidemic (HIV prevalence of more than 1% in the general population), and predominantly low-income countries with generally weak health systems and where HIV is mostly heterosexually transmitted. Twenty-three (23) second-order constructs were generated and summarised into eight (8) third-order constructs (Table 2). The findings are derived from second-order constructs and are categorised into enabling and deterring factors.

Enabling factors for HIV testing

Poor health or death of sexual partner or child

Physical deterioration of health [30, 32, 37, 39, 40, 43, 46, 48],[55, 67, 69] and poor health/death of sexual partner or child [31, 43, 48, 59, 68] elevated the perceived risk of infection and a decision to test:

“My husband passed away two years ago, he had TB [tuberculosis]. I also looked after my daughter who was sick for a long time before she passed away and so my mind was not settled as I was suspecting that I could have acquired the deadly virus. When I heard that VCT was taking place today, I decided to put my mind at rest by being tested.” (Female Tester, Zimbabwe) [43].

Experience of a sexually transmitted infection sometimes heightened risk perception [42, 59] as did personal contact with or knowing someone who had died of AIDS [28, 40, 49], thus increasing the willingness to test. Experiences of multiple sexual partners and perceived partner unfaithfulness also created as sense of vulnerability and therefore encouraged uptake of HIV testing [32, 48, 59, 60].

While heightened risk of HIV infection triggered uptake of HIV testing, sometimes it dissuaded people from testing as some assumed that they were already infected [36, 40, 55, 62].

Availability of life-prolonging antiretroviral therapy

While HIV was previously perceived as a ‘death sentence’, the increasingly wider availability of life-saving medication in many countries of SSA has shifted this notion. In some countries of SSA, this was found to be an incentive to test [30, 55, 59, 64–66, 69]. Therefore, testing and knowing one’s HIV status was no longer associated with death, but as a path to start treatment and prolong one’s life. For pregnant women, and despite the reported existence of gender inequality in health seeking decision making, testing was often undertaken as maternal obligation to protect the unborn child from HIV infection [29, 34, 40–42, 44, 47, 52, 54, 58].

“I tested the time I was pregnant. I wanted to know if I was negative or positive, and I didn’t want to put my baby at risk…” (Woman respondent, South Africa)[34].

HIV testing as preparation for marriage

In other instances, HIV testing was undertaken as an essential part of preparation for marriage [31, 39, 40, 42, 46, 50, 58, 61]. For instance, a study in Ghana [50] encapsulates the role that the church was playing in increasing the uptake of HIV testing as an integral part of marriage preparation and counselling. As part of marital rituals, the church required prospective couples to seek HIV testing before the church could sanction such marriages. Explaining how this ‘mandatory’ strategy came about, one study participant noted that:

“We had an HIV/AIDS awareness programme in our church…After an expert delivered a lecture, we were shocked at the numbers… we decided all those who are planning to marry must be tested for HIV/AIDS… We wanted to protect our future generations…” (Respondent, Ghana) [50].

Organisation and delivery of HIV testing

The roll-out of diverse HIV testing initiatives has contributed towards uptake of HIV testing. The implementation of ‘opt-out’ provider-initiated HIV testing - HIV testing and counselling which is recommended by health care providers to persons seeking health care services as a standard component of medical care - has contributed to increased uptake of HIV testing. For instance, service users reported being tested at antenatal care [41, 54, 57, 58, 62], or as TB patients [30, 45, 68] as an integral part of health care. This strategy was sometimes regarded as non-voluntary. Individuals sometimes acquiesced to the pressure by service providers to test:

“Although they say its voluntary, but they put pressure on you to test for it….If you don’t want to do it then, they must say ‘Okay, tell us when you feel comfortable for an HIV test.”’ (23-year old female tester, South Africa)[30].

Similarly, bringing testing services closer to the people through outreach mobile HIV testing attenuated (opportunity) costs of travelling and waiting times [33–35, 49], and provision of free testing services in Kenya [63], and expectations/provision of material benefits (i.e. food relief) encouraged uptake of HIV testing [43, 63, 67]. The use of non-familiar counsellors through mobile VCT was viewed as enhancing confidentiality, thus improving uptake of HIV testing [33, 43, 60].

Social network influence and support

Decision making about HIV testing were inextricably linked to social network influence [36–38, 40, 42, 49, 56–58, 67]. A study in Zambia [38] poignantly describes how individuals sought the views and support of their peers and family members during the decision making process about seeking HIV testing. In part, this was because friends and family members were crucial sources of psychosocial support and for family members a critical source of economic support:

“In the first place I never wanted to go there [for an HIV test], but I consulted my sister. She said no and I also said no. But afterwards I asked my brother who said . . . you should go for VCT, so that is when I went.” (Male tester, Zambia) [38].

Deterrents to HIV testing

Perceived low risk of infection

One recurring theme was that across SSA, individuals self-assessed their risk of infection. Lay interpretations of being at low risk of infection [43–45, 49], sometimes because of abstaining from sex or lacking a sexual partner [32, 33, 42, 51] negatively affected uptake of HIV testing. Proxy testing - adopting the status of sexual partner - was sometimes used as a risk estimate and a representation of one’s own HIV status [38, 60]. Some people felt they were at low risk of infection because they trusted their partner [44, 45, 50–52, 65] or because HIV was mainly perceived as a problem for sex workers [39–41]. A lack of physical symptoms or deterioration of health was also perceived as a sign of not being infected [33, 34, 65, 69]. In low prevalence settings like Mali [28], not knowing someone with HIV or who had died of AIDS created a perception of being at low risk of infection, thus undermining uptake of HIV testing.

Stigma, social exclusion and gendered relationships

Fear of stigma was another dominant theme for the low uptake of HIV testing in many settings of SSA [28–32, 34, 36–40, 45, 46, 49, 51–55, 60],[61, 63, 67–69]. Particularly because HIV transmission is predominantly heterosexual across SSA, being seen at a testing centre was synonymous with sexual promiscuity and assumed HIV-positive status [34, 51, 52, 60, 61]. For TB patients in South Africa, Ethiopia and Cameroon [30, 45, 68], the prospects of dealing with potential ‘double’ TB/HIV stigma acted as disincentive to test. The fear of HIV-related stigma is reflected in the following:

‘Even if I am already infected, nobody knows and it causes me no problems, at least for now. Imagine I go and do the testing and I find out I am positive, for how long will I hide it? Once people get to know I will be finished. My family will shun me. My friends will desert me. I will not be able to get a decent job. That is dying even before the infection kills me.’ (25-year old female non-tester, Nigeria) [39].

A study in Tanzania [64] found that while the effect of ART on improving corporeal health had motivated uptake of HIV testing, a new form of stigma had emerged in which individuals on ART were stigmatised as they were viewed as being responsible for the continued spread of HIV on account of them living longer with HIV. This in turn undermined uptake of HIV testing.

Across the sub-regions of SSA, fear of social exclusion also negatively influenced uptake of HIV testing [37, 38, 42, 49, 56, 58, 64, 67]. The fear of losing social support [38–40, 42, 64] and sexual partners [36, 37, 64, 67], and the fear of straining marital relationships, including possibilities of abandonment, divorce, or even violence [35, 43, 68, 69] inhibited uptake of HIV testing. The desire to marry also weighed heavily on people’s mind and a positive sero-status was viewed as threatening the chances of finding a marriage partner [34, 61, 67, 69]. In Uganda, there was fear that where discordance arose, test results could be used as confirmation of infidelity which could strain marital relationships [52, 62].

Within marital relationships, gender inequality affected women’s uptake of HIV testing. Studies in South Africa, Uganda and Tanzania found that men enjoyed decision-making autonomy on HIV testing [30, 42, 57]. Most studies reported women lacking control over their health; decisions about seeking HIV testing had to be discussed with, and permission obtained from, spouses [30–32, 35, 43, 44, 47, 51, 52, 55],[57, 62, 68]. In Tanzania and Zimbabwe, obtaining consent still raised suspicions of possible infidelity [31, 43] and those found HIV positive risked being blamed for contracting HIV [37, 47, 57, 68]. Thus HIV testing was shunned to avoid straining marital relationships. In Malawi, Uganda and Zimbabwe, men refused to test since this was at odds with masculine identity of self-confidence, resilience and stoicism [36, 67]. In Zambia, one study found that if the wife suggested testing, this was viewed by men as undermining their role as decision makers [37].

Quality of HIV testing services

Across sub-regional settings of SSA, individual perceptions of and experiences with the health care system undermined uptake of HIV testing. Perceived lack of confidentiality by health staff [29, 32, 40, 43, 46, 49, 55, 60],[68]; perceived lack of confidence in the competence of health personnel [28, 29, 40]; and perceived poor attitude of health staff [52, 53] dissuaded people from testing. Perceived unreliability of test results in Malawi and Uganda [33, 36, 42] and distrust of HIV testing technologies in Uganda and Zambia [42, 61] discouraged uptake of HIV testing. Describing his concerns about confidentiality, one respondent in Malawi said:

“It’s because if I can be tested at Mhojo Health Centre, VCT counsellors there know me and if that counselor at the VCT [centre] finds me with the virus then he can start spreading the messages to friends of mine, and if I know about that then it becomes very bad to my life, that’s why to be tested with someone else whom you never know it’s good” (Male, 48 years old, Malawi) [33].

Similarly, at health facilities, perceived poor location of testing facilities undermined uptake of HIV testing [34, 51, 52, 60, 61, 69]. Secluded testing facilities or use of VCT-specific clinic cards created social visibility of seeking HIV testing and assumption of being sexually active and/or already being infected. Where couple counselling was conducted at antenatal clinics, men perceived the testing sites as feminised settings, and therefore out of bounds [30, 35, 52, 57, 67].

Trust in the health care system and conspiratorial beliefs

Although not universally held across SSA, conspiratorial beliefs about HIV being a ‘western plot’ to dominate SSA were reported in Mali and Zambia [28, 61]. This inhibited uptake of HIV testing. These conspiracy views were nested within historical discourse about “colonial projects [which] turned African patients into objects to be studied and scrutinised, categorised and measured” [61]. In Mali [28], HIV was viewed as an invention to halt the growth of the African population or to sell western bio-medical products. Promotion of HIV testing by western countries as a gateway to accessing treatment and living a longer, healthy life was therefore viewed as a ploy to expand western countries’ interests:

“In reality, AIDS is an invention to sell condoms. The West created the idea of AIDS to put a stop to sexual relations or even better it’s a policy to put a brake on the growth of the African population.”(23-year old male non-tester, Mali)[28].

While HIV testing services were increasingly provided free of charge in many settings of SSA, this ‘gift’ by western countries and agencies or their local affiliates was viewed as attempts to further subjugate the weak African populations and to benefit western countries. As one old man in Zambia put it:

“Look around you, who is making money off of this disease? It is not Zambians. It is you [white Westerners]. This is why people are suspicious of this disease. This is why they think it [AIDS] was brought in from the outside.” (Male respondent, Zambia) [61].

Where religious discourse was dominant, a study in a rural setting of Zambia found that distrust of drawing blood for Satanic motives (synonymous with vampires), and perception of western medical technologies as instruments of the ‘devil’ created apprehension about HIV testing [61]. HIV testing was viewed as plunging an individual into ‘spiritual darkness, pain, loneliness and death’ [61].

Financial costs of accessing HIV testing

In the context of fragile livelihoods, the direct and indirect financial costs of accessing testing services inhibited uptake of testing [33, 36, 42, 50, 52, 56, 63]. Although HIV testing had become increasingly free in many settings of SSA in order to improve access levels, where user fees were charged, individuals weighed the benefits of testing against other competing human needs [33, 35, 39, 42, 47, 50]. More so, the indirect opportunity costs of suspending income generating activities and time-off work discouraged uptake of HIV testing [42, 50, 57, 67]. One respondent in Nigeria said:

“It costs 1000 Naira (approximately 8 US Dollars) to do blood test for HIV in the laboratories in Enugu. That is the minimum you can get it. I even heard that it costs more than that in some laboratories. So, why would I spend that amount of money to find out if I am HIV positive or not?” (24-year old non-tester, Nigeria) [39].

Perceived psychological burden of living with HIV

The motivation to test also depended on a person’s perceived ability to manage HIV. Even with availability of life-prolonging treatment, in many settings of SSA, a positive-HIV test result was still associated with death [29, 33, 34, 38, 40, 42, 43, 47],[48, 54, 55, 60, 65, 69] and mental distress was anticipated [32, 34, 36, 61, 69] with an HIV positive test causing an individual to ‘begin to think too much.’ This was perceived as hastening physical deterioration of health:

“Why look for troubles; I will never do a test. I cannot look for my death. I am afraid of dying. Haven’t you seen those who go for counselling? They are the ones who die very soon.”(Male non-tester, Tanzania) [47]

The reported absence of, or limited access to, treatment in some settings was a disincentive to test [32, 40, 48, 54, 55, 65, 66, 68]. Similarly, given the prevalence of HIV-TB co-infection, TB patients in Cameroon and South Africa avoided HIV testing to avoid the burden of being on dual strong treatment regimens for two diseases [30, 68].

Discussion: synthesis and line-of-argument

This synthesis shows that uptake of HIV testing in SSA is influenced by an array of individual, relational and contextual-based factors. While SSA is not a homogeneous setting, our synthesis suggests that the barriers and facilitators are comparable across SSA. It is worth pointing out that the factors influencing uptake of HIV testing are not mutually exclusive. As depicted by our conceptual model (Figure 2), they are inextricably linked and may coalesce or reinforce one another to influence uptake of HIV testing. Based on the analysis and interpretation of second-order constructs, high-level third-order constructs were developed (Table 2) to form a ‘line of argument’ about factors influencing uptake of HIV testing in SSA. These are condensed into four themes (Figure 2) and discussed as below:

Lay construction of risk of infection and health

First, one dominant factor that influences uptake of HIV testing is lay construction of risk and health. Individuals engage in intense activity of experience-sorting and interpretation as they situate themselves in terms of danger [70]. This lay assessment is informed by individuals’ knowledge of own and partner’s sexual behaviour and observations and experiences of their health [71]. This lay analysis influences behaviour in two different ways. While heightened risk of infection provides impetus to test, there is also a disjunction between perceived risk of HIV infection and uptake of testing, as those who perceive themselves as being infected already do not see the value of knowing their HIV status. Thus, HIV testing is more often undertaken when there is clear decline in health status which necessitates access to health care.

Related to physical health is the psychological burden of living with HIV. Despite the increasingly wider availability of antiretroviral therapy in most parts of SSA, its impact on uptake of HIV testing still remains mixed. This is because while treatment is saving lives and has ‘normalised’ HIV from a fatal to a chronic condition, its incurable nature reduces the motivation to test (Figure 2). Knowing one’s HIV status is viewed as imposing an inordinate psychological burden and is associated with imminent death. HIV testing is therefore undertaken when it is an absolute necessity – when diagnosis is needed to access health care [69].

Trust in the health system and conspiratorial beliefs

Second, even when individuals view themselves at risk of HIV infection and/or are willing to seek HIV testing, uptake of testing is influenced by people’s trust in the health care system and providers (Figure 2). The lack of trust manifests itself in lack of confidence in individual health workers and trust in the health institution as a whole [72]. Perceived poor quality of health services as characterised by inability by health workers to maintain confidentiality, perceived poor calibre of health workers and lack of trust in testing technologies inhibit uptake of testing. As Gilson has noted, health systems are social institutions and therefore people’s perceptions of and experiences with the health care system is crucial in influencing service utilisation which even good technical care may not remedy [73]. Studies on trust conducted in the United States of America have reported how distrust of health providers and health system as a whole affect utilisation of HIV services [74–76]. For instance, one study reported that trust in physicians was associated with acceptance of ART and a minority of individuals that felt mistreated by health care providers were resistant to accepting ART [74]. Narratives from the synthesis indicate that lack of trust in health care providers was attenuated by the provision of HIV testing through non-facility based HIV testing by non-familiar providers, thus improving uptake of HIV testing (Figure 2).

Another dimension of lack of trust in the health system relates to conspiracy narratives (Figure 2). In a few settings of SSA, HIV and HIV testing were viewed as western countries’ insidious ways of dominating SSA. HIV testing was viewed as being used to benefit western countries through creation of market for bio-medical products [28] and job opportunities for its citizens [61]. These geo-political conspiratorial beliefs sometimes coalesce with religious discourse. In Zambia for instance, blood drawn for HIV testing was viewed as being used for satanic rituals [61, 77]. These findings corroborate previous medical research conducted in Gambia and Zambia where local people were highly suspicious of and shunned medical tests which involved the drawing of blood [78, 79].

Social triad: Stigma, gendered influence and reproductive health aspirations

Third, HIV testing behaviour is strongly socially delineated. Social relationships play a significant role in influencing HIV testing behaviour through social influence and perceived (lack of) social support (Figure 2). For instance, in the absence of strong formal safety nets, social capital is central to survival. Therefore, the desire to preserve social relationships and identity inhibit uptake of HIV testing. This is because while individuals may acknowledge the importance of knowing their HIV status and even show willingness to seek testing in response to (perceived) decline in health or because of previous sexual risk behaviour, ultimate decision making and attitude towards testing is influenced by concerns about anticipated stigma, which is sometimes inextricably linked to possible loss of economic support. Thus, being found HIV positive represents an undesirable characteristic, a ‘spoiled identity’ [80] from which individuals try to distance themselves.

Paradoxically, while the availability of treatment has become an incentive to test, a new form of stigma has emerged. A study in Tanzania [64] found that while ART roll-out had led to the ‘normalisation’ of HIV and thus stimulated uptake of testing, the stigmatisation of people on treatment that they ‘spread the disease’ also undermined uptake of HIV testing.

Gendered power relationships also undermine uptake of HIV testing (Figure 2). In most parts of SSA, ultimate authority on health care seeking lies with men [81, 82] and communication with, and support from, partners improves uptake of HIV testing by women [83, 84]. This was a common narrative amongst women in some of the synthesised papers. Their lack of access to and control over financial resources affected their access to and utilisation of HIV testing services. Conversely as primary caregivers, their subordinate role in decision making about HIV testing was mitigated by their regular contact with reproductive and child health services, thus being able to utilise HIV testing services. The onset of provider-initiated HIV testing also absolved women from blame for testing without their partners’ consent by shifting attention to testing as part of routine health care.

Similarly, the uptake of HIV testing is inextricably linked to individuals’ marital and reproductive health aspirations. Thus, marriage and parenthood represent social duties, expectations and individual aspirations [85], and a connection with one’s community [86, 87]. This affects uptake of HIV testing behaviour in two opposing ways. As an enabler, both men and women sought HIV testing as preparation for marriage or achieving reproductive health aspirations. Those that had never tested claimed willingness to seek HIV testing when it was time to get married. For women, as Fortes has put it, “the achievement of parenthood is regarded as a sine qua non for the attainment of the full development as a complete person to which all aspire....and a woman becomes a woman when she becomes able to bear children and continued child bearing is irrefutable evidence of continued femininity” [86].

Narratives from the synthesised papers suggest that HIV testing was accepted during antenatal care primarily because it was essential for achieving reproductive health aspirations and as a moral and social obligation to give birth to a healthy child. On the other hand, both men and women declined HIV testing for fear of straining marital relationship or undermining chances of finding a marriage partner.

Organisation and delivery of HIV testing: mitigating the financial and social costs

Lastly, the synthesis shows that uptake of HIV testing is influenced by the way HIV services are delivered. Where user-fees are charged or services are far away, investment in health (HIV testing) competes with, and is ranked low in relation to, other immediate human needs. This is because, for people in precarious living conditions, access to, and utilisation of, health care imposes inordinate opportunity costs [81]. However, the roll-out of different HIV testing initiatives such as mobile HIV testing services, provider-initiated HIV testing, home-based HIV testing [88] has mitigated these barriers such as distance, financial costs, long waiting times, inconvenient testing hours, and allayed fears of perceived lack of confidentiality [10, 89, 90]. When individuals are in contact with the health system for other health conditions, provider-initiated HIV testing ensures uptake of testing not only because it is necessary and is conveniently available at the time of seeking medical attention, but also because it helps preserve service users’ sense of moral worth by not making assumptions about their behaviour which could lead to stigmatisation [91]. The drawback is that men shunned testing services even if they were readily available if they viewed them as being provided in settings perceived as ‘female spaces’ such as antenatal clinics [92].

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this synthesis lies in the extensive search of literature. The inclusion of papers utilising different methodological approaches, including mixed-methods papers provided in-depth insight into factors that influence uptake of HIV testing. Also, like previous studies that have used the meta-ethnography approach [17, 20, 22, 25, 26], not using pre-determined quality assessment criteria or excluding papers on the basis of pre-specified quality assessment criteria enabled us to draw on the ‘richness’ of these papers. Using a multi-disciplinary team also enriched the synthesis by enabling us to draw and collate team members’ interpretations of the findings. However, an inherent weakness of this synthesis is the possibility of having missed some publications. We tried to mitigate this by scouring references of selected papers and manually searching the data bases. Another limitation of this synthesis is that due to language constraints, we only included papers published in English. Similarly, due to publication restrictions, the context of the synthesised studies were not extensively described thereby limiting detailed contextualisation of the synthesised findings and comparing the findings across different settings.

Conclusions

Uptake of HIV testing in SSA is influenced by an array of often inter-linked factors. Despite the heterogeneity of SSA, our findings suggest that there is a strong similarity in the barriers to and facilitators of HIV testing across SSA. Lay interpretation of risk of infection either encourages or discourages uptake of HIV testing. Depending on past sexual lifestyles and the state of individual, marital partner and child’s corporeal health, individuals construct own probabilities of being infected. While direct and indirect financial costs inhibit uptake of HIV testing, access to HIV testing is also deeply engendered, and individuals also have to balance the social benefits and costs of seeking HIV testing. Although the wider availability of HIV testing and treatment services and roll-out of various HIV testing strategies has contributed towards increased uptake of HIV testing, lack of confidence in the health system and conspiratorial beliefs undermine testing uptake. Even though the enablers and barriers to uptake of HIV testing cut across many settings of SSA, interventions aimed at increasing uptake still need to be context specific, sustaining the enabling factors and concurrently addressing the barriers.

Policy and practical implications

The synthesis suggests that the policy of provider-initiated HIV testing coupled with increased wider availability of life-saving HIV medication is crucial in scaling up uptake of HIV testing in SSA. Due to fear associated with seeking HIV testing, availability and convenience of provider-initiated HIV testing provides that extra ‘push’ that enables individuals to overcome barriers and effect their intentions to test and at the same time assuage fear of stigma and attenuate costs. This, therefore, calls for stepping up provider-initiated HIV testing when individuals come into contact with the health system.

At practical level, our synthesis suggests the need for scaling up and sustaining the roll-out of different and locality-specific HIV testing models i.e. mobile HIV testing to respond to the peculiarities of each setting, even within the same country. Improving quality of HIV service delivery, particularly ensuring confidentiality - which many studies identified as a barrier - is also vital. Interventions such as home-based HIV testing that focus on social network relationships (i.e. couples and households) rather than individual-focused interventions are also critical given inequitable power dynamics and the significance of social networks in decision-making processes about HIV testing. Such strategies could also help assuage fears of confidentiality as reported in many studies as well as attenuate direct and indirect financial costs of seeking HIV testing. Given the reported persistence of stigma, continued sensitization campaigns are need. Also, provision of HIV testing interventions particularly in non-clinical settings need to be combined with screening for other less stigmatizing health conditions to avoid stigma associated with being seen accessing HIV testing. Most crucially too, through sensitization campaigns, there is need to focus on addressing socially constructed individual risk assessments, especially in low HIV prevalence settings where HIV may be viewed as unreal and a far-off threat. In settings where mistrust and conspiratorial beliefs about HIV and HIV testing exist, these need to be addressed through sensitization campaigns.

References

Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS: UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2011. 2011, Geneva: UNAIDS, Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC221_WorldAIDSday_report_2011_en.pdf. Accessed on 11 January 2013

WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF: Global AIDS Response-Progress Report 2011. 2011, Geneva: WHO, Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/. Accessed on 22 February 2012

Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS: Getting to zero-2011-2015 Strategy. 2010, Geneva: UNAIDS, Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/20101221_JC2034E_UNAIDS-Strategy_en.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2011

WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF: Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS Intervention in the health sector - Progress Report. 2009, Geneva: UNAIDS, Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2009progressreport/en/. (Accessed: 7 November 2010)

WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF: Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS Intervention in the health sector-Progress Report 2010. 2010, Geneva: WHO, Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2010progressreport/report/en/. (Accessed on 4 August 2011

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC: HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003, 79 (6): 442-7. 10.1136/sti.79.6.442.

Nakanjako D, Kamya M, Kyabayinze D, Mayanja-Kizza H, Freers J, Whalen C, Katabira E: Acceptance of routine testing for HIV among adult patients at the medical emergency unit at a national referral hospital in Kampala. AIDS Behav. 2006, 11: 753-758.

Van Dyk AC, van Dyk PJ: “To know or not to know:” Service-related barriers to voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) in South Africa. Curationis. 2003, 26: 4-10.

Marum E, Taegtmeyer M, Chebet K: Scale-up of voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Kenya. JAMA. 2006, 296 (7): 859-862. 10.1001/jama.296.7.859.

Fylkesness K, Siziya S: A randomised trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counselling and testing. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9 (5): 566-72. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01231.x.

Mutale W, Michelo C, Jürgensen M, Fylkesness K: Home-based voluntary counselling and testing found highly acceptable and to reduce inequalities. BMC Publ Health. 2010, 10: 347-10.1186/1471-2458-10-347.

Warwick Z: The influence of antiretroviral therapy on the uptake of HIV testing in Tutume, Botswana. Int J STD AIDS. 2006, 17 (7): 479-81. 10.1258/095646206777689189.

Noblit GW, Hare RD: Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. 1988, Newbury Park, California: Sage

Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R: Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002, 7: 209-215. 10.1258/135581902320432732.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, Donovan J: Evaluating meta-ethnography: A synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 56 (4): 671-84. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00064-3.

Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, Yardley L, Pope C, Daker-White G, Campbell R: Resisting medicines: A synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (1): 133-55. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063.

Merten S, Kenter E, McKenzie O, Musheke M, Ntalasha H, Martin-Hilber A: Patient-reported barriers and drivers of adherence to antiretrovirals in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-ethnography. Trop Med Int Health. 2010, 15 (1): 1-18.

Harvey D: Understanding Australian rural women’s ways of achieving health and wellness-a meta synthesis of the literature. Rural Remote Heal. 2007, 7 (4): 823-

Walsh D, Downe S: Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005, 50 (2): 204-211. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x.

Smith LK, Pope LC, Botha JL: Patients’ health seeking and delay in cancer presentation: A qualitative synthesis. Lancet. 2005, 366 (9488): 825-31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67030-4.

Mays N, Pope C: Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000, 320 (7226): 50-2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50.

Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J: Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2007, 4 (7): e238-10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238.

Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J: Conducting a meta ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons Learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008, 8: 21-10.1186/1471-2288-8-21.

Rolfe G: Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: Quality and the idea of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2006, 53 (3): 304-10. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x.

Briggs M, Flemming K: Living with leg ulceration: a synthesis of qualitative findings. J Adv Nurs. 2007, 59 (4): 319-28. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04348.x.

Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, Walter F, Feder G, Ridd M, Kessler D: “Medication career” or “Moral careers”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 68 (1): 154-68. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068.

Barbour RS: Checklist for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog?. BMJ. 2001, 322 (7294): 1115-7. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

Castle S: Doubting the existence of AIDS: A barrier to voluntary HIV testing and counselling in urban Mali. Health Policy Plan. 2003, 18 (2): 146-55. 10.1093/heapol/czg019.

Pool R, Nyanzi S, Whitworth JAG: Attitude to voluntary counselling and testing for HIV among pregnant women in rural south-west Uganda. AIDS Care. 2001, 13 (5): 605-15. 10.1080/09540120120063232.

Daftary A, Padayatchi N, Padilla M: HIV testing and disclosure: A qualitative analysis of TB patients in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007, 19 (4): 572-7. 10.1080/09540120701203931.

Maman S, Mbwambo J, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Sweat M: Women’s barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: Challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care. 2001, 13 (5): 595-603. 10.1080/09540120120063223.

Mabunda G: Voluntary counselling and testing: Knowledge and practices in a rural South African village. J Transcult Nurs. 2006, 17 (1): 23-9. 10.1177/1043659605281978.

Angotti N, Bula A, Gaydosh L, Kimchi EZ, Thornton RL, Yeatman SE: Increasing the acceptability of HIV counselling and testing with three C’s: Convenience, Confidentiality and Credibility. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 68 (12): 2263-70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.041.

McPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H: “You must do the test to know your status”: Attitude to HIV voluntary counselling and testing for adolescents among South Africa Youth and Parents. Health Educ Behav. 2008, 35 (1): 87-104.

Mlay R, Lugina H, Becker S: Couple counselling and testing for HIV at antenatal clinics: Views from men, women and counsellors. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (3): 356-60. 10.1080/09540120701561304.

Izugbara CO, Undie CC, Mudege NN, Ezeh AC: Male youth and voluntary counselling and HIV-testing: The case of Malawi and Uganda. Sex Educ. 2009, 9 (3): 243-59. 10.1080/14681810903059078.

Grant E, Logie D, Masura M, Gorman D, Murray SA: Factors facilitating and challenging access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a township in the Zambian Copperbelt: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (10): 1155-60. 10.1080/09540120701854634.

Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD: The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: Do families and friends matter?. AIDS Care. 2008, 20 (1): 101-5. 10.1080/09540120701427498.

Oshi SN, Ezugwu FO, Oshi DC, Dimkpa U, Korie FC, Okperi BO: Does self perception of risk of HIV infection make the youth to reduce risky behaviour and seek voluntary counselling and testing services? A case study of Nigerian Youth. J Soc Sci. 2007, 14 (2): 195-203.

Meiberg AE, Bos AER, Onya HE, Schaalma HP: Fear of stigmatization as barrier to voluntary HIV counselling and testing in South Africa. East Afri J Public Health. 2008, 5 (2): 49-54.

Groves AK, Maman S, Msomi S, Makhanya N, Moodley D: The complexity of consent: women's experiences testing for HIV at an antenatal clinic in Durban, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010, 22 (5): 538-44. 10.1080/09540120903311508.

Råssjö EB, Darj E, Konde-Lule J, Olsson P: Responses to VCT for HIV among young people in Kampala, Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res. 2007, 6 (3): 215-222. 10.2989/16085900709490417.

Chirawu P, Langhaug L, Mavhu W, Pascoe S, Dirawo J, Cowan F: Acceptability and challenges of implementing voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) in rural Zimbabwe: Evidence from the Regai Dzive Shiri Project. AIDS Care. 2010, 22 (1): 81-8. 10.1080/09540120903012577.

De Paoli MM, Manongi R, Klepp K: Factors influencing acceptability of voluntary counselling and HIV-testing among pregnant women in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2004, 16 (4): 411-25. 10.1080/09540120410001683358.

Ayenew A, Leykun A, Colebunders R, Deribew A: Predictors of HIV testing among patients with Tuberculosis in north-west Ethiopia: A case–control Study. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (3): e9702-10.1371/journal.pone.0009702.

Namakhoma I, Bongololo G, Bello G, Nyirenda L, Phoya A, Phiri S, Theobald S, Obermeyer CM: Negotiating multiple barriers: health workers' access to counselling, testing and treatment in Malawi. AIDS Care. 2010, 22 (Suppl 1): 68-76.

Urassa P, Gosling R, Pool R, Reyburn H: Attitudes to voluntary counselling and testing prior to the offer of nevirapine to prevent vertical transmission of HIV in northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2005, 17 (7): 842-52. 10.1080/09540120500038231.

Obermeyer CM, Sankara A, Bastien V, Parsons M: Gender and HIV testing in Burkina Faso: An exploratory study. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69 (6): 877-84. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.003.

Bhagwanjee A, Petersen I, Akintola O, George G: Bridging the gap between VCT and HIV/AIDS treatment uptake: Perspectives from a mining-sector workplace in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008, 7 (3): 271-279. 10.2989/AJAR.2008.7.3.4.651.

Luginaah IN, Yiridoe EK, Taabazuing MM: From mandatory to voluntary testing: Balancing human rights, religious and cultural values, and HIV/AIDS prevention in Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (8): 1689-700. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.034.

Taegtmeyer M, Kilonzo N, Mung’ala L, Morgan G, Theobald S: Using gender analysis to build voluntary counseling and testing responses in Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 100 (4): 305-11. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.001.

Larsson EC, Thorson A, Nsabagasani X, Namusoko S, Popenoe R, Ekström AM: Mistrust in marriage-Reasons why men do not accept couple HIV testing during antenatal care-a qualitative study in eastern Uganda. BMC Publ Health. 2010, 10: 769-10.1186/1471-2458-10-769.

Varga C, Brookes H: Factors influencing teen mothers' enrollment and participation in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in Limpopo province, South Africa. Qual Health Res. 2008, 18 (6): 786-802. 10.1177/1049732308318449.

Sherr L, Hackman N, Mfenyana K, Chandia J, Yogeswaran P: Research Report: Antenatal HIV testing from the perspective of pregnant women and health clinic staff in South Africa-implications for pre- and post-test counselling. Couns Psychol Q. 2003, 16 (4): 337-347. 10.1080/0951507032000156880.

Simpson A: Christian identity and men's attitudes to antiretroviral therapy in Zambia. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010, 9 (4): 397-405. 10.2989/16085906.2010.545650.

Nuwaha F, Kabatesi D, Muganwa M, Whalen CC: Factors influencing acceptability of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in Bushemi district of Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2002, 79 (12): 626-632.

Theuring S, Mbezi P, Luvanda H, Jordan-Harder B, Kunz A, Harms G: Male involvement in PMTCT services in Mbeya region, Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13 (Suppl 1): 92-102.

Mbonye AK, Hansen K, Wamono F, Magnussen P: Barriers to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in Uganda. J Bio soc Sci. 2010, 42 (2): 271-83.

Levy JM: Women’s expectations of treatment and care after an antenatal HIV diagnosis in Lilongwe, Malawi. Reprod Health Matters. 2009, 17 (33): 152-61. 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33436-9.

Bwambale FM, Ssali SN, Byaruhanga S, Kalyango JN, Karamagi CAS: Voluntary HIV counselling and testing among men in rural western Uganda: Implications for HIV prevention. BMC Publ Health. 2008, 8: 263-10.1186/1471-2458-8-263.

Frank E: The relation of HIV testing and treatment to identity formation in Zambia. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009, 8 (4): 515-524. 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.4.15.1052.

Larsson EC, Thorson A, Pariyo G, Conrad P, Arinaitwe M, Kemigisa M, Eriksen J, Tomson G, Ekström AM: Opt-out HIV testing during antenatal care: Experiences of pregnant women in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27 (1): 69-75. 10.1093/heapol/czr009.

Dye TDV, Apondi R, Lugada E: A qualitative assessment of participation in a rapid scale-up, diagonally-integrated MDG-related disease prevention campaign in rural Kenya. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (1): e14551-10.1371/journal.pone.0014551.

Roura M, Urassa M, Busza J, Mbata D, Wringe A, Zaba B: Scaling up stigma? The effects of antiretroviral roll-out on stigma and HIV testing. Early evidence from rural Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2009, 85 (4): 308-12. 10.1136/sti.2008.033183.

Day JH, Miyamura K, Grant AD, Leeuw A, Munsamy J, Baggaley R, Churchyard GJ: Attitudes to HIV voluntary counselling and testing among mineworkers in South Africa: Will availability of antiretroviral therapy encourage testing?. AIDS Care. 2003, 15 (5): 665-72. 10.1080/0954012030001595140.

Phakathi Z, Van Rooyen H, Fritz K, Richter L: The influence of antiretroviral treatment on willingness to test: A qualitative study in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2011, 10 (2): 173-180. 10.2989/16085906.2011.593381.

Skovdal M, Campbell C, Madanhire C, Mupambireyi Z, Nyamukapa C, Greyson S: Masculinity as a barrier to men’s use of HIV services in Zimbabwe. Global Health. 2011, 7 (1): 13-10.1186/1744-8603-7-13.

Njozing NB, Edin KE, Hurtig AN: When I get better I will do the test’: Facilitators and barriers to HIV testing in northwest region of Cameroon with implications for TB and HIV/AIDS control programmes. SAHARA J. 2010, 7 (4): 24-32. 10.1080/17290376.2010.9724974.

Jürgensen M, Tuba M, Fylkesnes K, Blystad A: The burden of knowing: balancing benefits and barriers in HIV testing decisions. A qualitative study from Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012, 12: 2-10.1186/1472-6963-12-2.

Warwick I, Aggleton P, Homans H: Constructing commonsense -Young people’s beliefs about AIDS. Sociol Health Illn. 1988, 10 (3): 213-231. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11340140.

Paicheler G: Perception of HIV risk and preventive strategies: A dynamic analysis. Health. 1999, 3 (1): 47-69.

Cunning CO, Sohler NL, Korin L, Gao W, Anastos K: HIV status, trust in health care providers and distrust in the health care system among Bronx women. AIDS Care. 2007, 19 (2): 226-34. 10.1080/09540120600774263.

Gilson L: Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 56 (7): 1453-68. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00142-9.

Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friendland GH: Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001, 28 (1): 47-58.

Whetten K, Lesserman J, Whetten R, Ostermann J, Thielman N, Swartz M, Stangl D: Exploring lack of trust in care providers and government as a barrier to health service use. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96: 716-721. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255.

Bogart LM, Thornburn S: Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans?. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 38 (2): 213-8. 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014.

Schumaker LL, Bond VA: Antiretroviral therapy in Zambia: colours, ‘spoiling’, ‘talk’ and the meaning of antiretrovirals. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 67 (12): 2126-34. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.006.

Fairhead J, Leach M, Small M: Where techno-science meets poverty: Medical research and the economy of blood in The Gambia, West Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63 (4): 1109-20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.018.

Kingori P, Muchimba M, Sikateyo B, Amadi B, Kelly P: ‘Rumours’ and clinical trials: a retrospective examination of a paediatric malnutrition study in Zambia, southern Africa. BMC Publ Health. 2010, 10: 556-10.1186/1471-2458-10-556.

Goffman E: Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. 1963, Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall

Tolhurst R, de Koning K, Price J, Kemp J, Theobald S, Squire SB: The challenges of infectious disease: Time to take gender into account. J Heal Manag. 2002, 4: 135-151. 10.1177/097206340200400204.

Tolhurst R, Amekudzi YP, Nyonator FK, Bertel SS, Theobald S: “He will ask why the child gets sick so often”: The gendered dynamics of intra-household bargaining over healthcare for children with fever in the Volta Region of Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66 (5): 1106-17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.032.

Bajunire F, Muzoora M: Barriers to the implementation of programmes for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: A cross-sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005, 2: 10-10.1186/1742-6405-2-10.

Sarker M, Sanou A, Snow R, Ganame J, Gondos A: Determinants of HIV counselling and testing participation in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2007, 12 (12): 1475-83. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01956.x.

Smith DJ, Mbakwem BC: Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: marriage, fertility and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007, 21 (Suppl 5): S37-41. 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af.

Fortes M: Parenthood, marriage and fertility in West Africa. J Dev Stud. 1978, 14 (4): 121-149. 10.1080/00220387808421692.

Hollos M, Larsen U: Motherhood in sub-Saharan Africa: The social consequences of infertility in an urban population in northern Tanzania. Cult Health Sex. 2008, 10 (2): 159-73. 10.1080/13691050701656789.

Matovu JK, Makumbi FE: Expanding access to voluntary HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: Alternative approaches for improving uptake, 2001–2007. Trop Med Int Health. 2007, 12 (11): 1315-22. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01923.x.

Ostermann J, Reddy EA, Shorter MM, Muiruri C, Mtalo A, Itemba DK, Njau B, Bartlett JA, Crump JA, Thielman NM: Who Tests, Who Doesn’t, and Why? Uptake of Mobile HIV Counselling and Testing in the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (1): e16488-10.1371/journal.pone.0016488.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care-Botswana, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004, 53 (46): 1083-6.

Obermeyer CM, Osborn M: The utilisation of testing and counselling for HIV: A review of the social and behavioural evidence. Am J Public Health. 2007, 97: 1762-1774. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096263.

Barker G, Ricardo C: Young men and the construction of masculinity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for HIV/AIDS, Conflict and Violence (Working Paper). 2005, Washington, DC: The World Bank

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/220/prepub

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the project ‘Improving equity of access to HIV care and treatment in Zambia.’ The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agency. The funding agency played no role in the design and conduct of the study, the interpretation of the data and the content of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MM, VB and SM conceptualized the study. MM, SG and OM did the literature search. MM and HN did the title and abstract review and all authors were involved in full-text review. MM drafted the first manuscript into which co-authors contributed input. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Musheke, M., Ntalasha, H., Gari, S. et al. A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 13, 220 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-220

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-220