Abstract

Background

Idiopathic environmental intolerance attributed to electromagnetic fields (IEI-EMF) remains a complex and unclear phenomenon, often characterized by the report of various, non-specific physical symptoms (NSPS) when an EMF source is present or perceived by the individual. The lack of validated criteria for defining and assessing IEI-EMF affects the quality of the relevant research, hindering not only the comparison or integration of study findings, but also the identification and management of patients by health care providers. The objective of this review was to evaluate and summarize the criteria that previous studies employed to identify IEI-EMF participants.

Methods

An extensive literature search was performed for studies published up to June 2011. We searched EMBASE, Medline, Psychinfo, Scopus and Web of Science. Additionally, citation analyses were performed for key papers, reference sections of relevant papers were searched, conference proceedings were examined and a literature database held by the Mobile Phones Research Unit of King’s College London was reviewed.

Results

Sixty-three studies were included. “Hypersensitivity to EMF” was the most frequently used descriptive term. Despite heterogeneity, the criteria predominantly used to identify IEI-EMF individuals were: 1. Self-report of being (hyper)sensitive to EMF. 2. Attribution of NSPS to at least one EMF source. 3. Absence of medical or psychiatric/psychological disorder capable of accounting for these symptoms 4. Symptoms should occur soon (up to 24 hours) after the individual perceives an exposure source or exposed area. (Hyper)sensitivity to EMF was either generalized (attribution to various EMF sources) or source-specific. Experimental studies used a larger number of criteria than those of observational design and performed more frequently a medical examination or interview as prerequisite for inclusion.

Conclusions

Considerable heterogeneity exists in the criteria used by the researchers to identify IEI-EMF, due to explicit differences in their conceptual frameworks. Further work is required to produce consensus criteria not only for research purposes but also for use in clinical practice. This could be achieved by the development of an international protocol enabling a clearly defined case definition for IEI-EMF and a validated screening tool, with active involvement of medical practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although the issue of idiopathic intolerances attributed to environmental exposures (IEI) first appeared in the scientific literature more than five decades ago [1], the possible underlying causes, as the term “idiopathic” suggests, remain unclear [2] and there is no widely accepted protocol for the identification of patients and treatment [3]. A representative example is the variety of physical symptoms without a clear pathological basis that are attributed by the patients to relatively low-level exposure to non-ionizing electromagnetic fields (EMF), emitted by sources such as mobile phone devices and base stations, high-voltage overhead powerlines, computer equipment and domestic appliances [4]. This phenomenon is better known within the public and scientific context as "electromagnetic hypersensitivity"(EHS), although since 2005 the term “Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance Attributed to EMF" (IEI-EMF) has been proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an etiologically neutral description [5]. In this paper, the descriptive term “IEI-EMF” is used.

According to the WHO [5], people with IEI-EMF are mainly characterized by the report of non-specific physical symptoms (NSPS), without a consistent pattern [6], such as redness, tingling, burning sensations in the facial area, fatigue, tiredness, lack of concentration, dizziness, nausea, heart palpitation and digestive disturbances. IEI-EMF is often accompanied by occupational, social and mental impairment [4, 7] and its estimated prevalence varies considerably, probably due to different methodological approaches; 1.5% in Sweden [6], 3.2% in California [8], 3.5% in Austria [9], 5% in Switzerland [10] and 13.4% in Taiwan [11]. Demographic characteristics such as age, gender and occupational status have repeatedly been associated with IEI-EMF [6, 10].

The experience and belief of IEI-EMF patients is in contrast with the scientific state of the art; results from systematic assessment of experimental and epidemiological evidence are consistent, concluding that a causal association of EMF exposure with symptomatic and other physiologic or cognitive reactions cannot be adequately supported [12–17]. IEI-EMF has been associated with psychological components [18–23] but their exact role is not clear. Although a possible effect of exposure cannot yet be ruled out because of methodological obstacles in research primarily regarding exposure assessment and study design [14, 16], more recent approaches stress the importance of looking into the interaction of environmental, biological, psychological and social pathways [24].

However, it is still controversial who should be categorised as having IEI-EMF. The lack of a validated, mutually accepted case definition and diagnostic instrument affects the quality of the research outcomes and increases the methodological heterogeneity, resulting in limited comparability between the studies. That stands in the way of a reliable estimation of the prevalence of IEI-EMF in the general population, proper meta-analysis of etiological evidence, the identification of health outcome patterns/profiles and contributes to a great deal of uncertainty regarding the characteristics, identification and management of this sensitivity by health care providers [25–27].

No systematic review has been performed yet focusing on the existing definitions and criteria for the identification of people with IEI-EMF. In light of the need to inform health care profesionals about relevant aspects of IEI-EMF and prepare the ground for discussion and consensus in the research community on widely supported case definition criteria, the present paper identified the relevant studies on IEI-EMF published to date, in order to summarize:

-

The descriptive terms used to define IEI-EMF.

-

The inclusion criteria and procedure for the identification of individuals with IEI-EMF.

Methods

Search strategy for the identification of studies

Initially, the following electronic databases were searched to detect relevant studies that were published from inception to April 2010: Embase (Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Medline (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland), PsychInfo (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC). Web of Knowledge (Institute for Scientific Information, The Thomson Corporation, Stamford, Connecticut) and Scopus (Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands). A wide range of (combined) keywords was used with regards to EMF exposure, sensitivity and related health outcomes, which is presented in Table 1. In addition to the electronic database searches, the reference sections of previous systematic reviews, key papers, international reports on EMF and health and research databases of websites focused on the issue of EMF such as the “EMF Portal” and the WHO webpage were checked for potentially relevant articles. A wide literature database held by the Mobile Phones Research Unit of King’s College London was also consulted. A second literature search was carried out in order to update our review with studies published from May 2010 to June 2011.

Inclusion criteria

Only primary studies written in English and published in the peer-reviewed literature were considered as suitable for inclusion in the current review. Conference presentations, brief communications and reviews were excluded. The primary condition to include a study was the report of use of at least one criterion to identify individuals with IEI-EMF. Studies focusing on health effects from wider environmental exposures (such as chemicals) were eligible as long as they attempted to identify sensitivity to EMF in their investigation. Studies recruiting exclusively “healthy” individuals without any attempt to assess IEI-EMF or identify relevant individuals were excluded. Since the “attribution” of health complaints to EMF is not necessarily synonymous with IEI-EMF and it is not an established prerequisite for its existence, studies relying solely on “attribution” without any mention of and explicit conceptual link with IEI-EMF or synonymous terms were not considered eligible for this review. Among papers based on the same sample and identifying criteria of IEI-EMF, the first publication was included.

Data extraction

For each included study, the following data were abstracted: reference and country, study design, methods and source of sample recruitment, IEI-EMF sample characteristics (such as sample size, age mean or range and gender distribution), type of sensitivity based on the triggering EMF source(s), the criteria used to identify individuals with IEI-EMF, exclusion criteria (based on self-report/interview or clinical examination) and the case definition procedure followed for the identification of IEI-EMF (such as self-report and/or medical examination to exclude the possibility that a diagnosed disorder was responsible for the reported health complaints) (Tables 2 and 3). The data provided in the tables were derived from the information that was given or could be inferred from the original publications. However, in some cases (part of) the necessary information was not provided in the reviewed articles.

Review Process

The literature search was performed by the first author and the evaluation of inclusion criteria by CB, IVK and GJR, with uncertainties resolved through consultation among all the authors. The initial screening was based on the titles and/or abstracts. Next, the hard copies of the potentially eligible publications were examined to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Search results

Figure 1 illustrates the literature search process. We examined 5328 citations in total and identified 35 experimental and 28 observational studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Study characteristics

When reported, sample sizes of subjects with IEI-EMF ranged between 1 to 100 in the experimental studies and from 2 to 2748 in the observational studies. The percentage of female participants (exempting case-studies) ranged between 0 to 81.3% and 50% to 100% respectively. In all studies, the reported mean age of IEI-EMF individuals varied between 26.1 and 55.5 years. IEI-EMF triggered by several different EMF sources (“general”) was the sensitivity type of primary focus in the included investigations (n = 48), while 14 studies concentrated exclusively on “source-specific” IEI-EMF and three on both “general” and “source-specific” IEI-EMF. There was a variety of synonyms of IEI-EMF in the literature such as "hypersensitivity (HS) to EMF", "electromagnetic Hypersensitivity (EHS)", "electrohypersensitivity", "environmental annoyance attributed to EMF", "electromagnetic distress syndrome" and "environmental illness". “Hypersensitivity to EMF” (and its variants) was by far the most frequently used definition/descriptive term (Figure 2). In 35 studies the case definition procedure was solely based on the subjective report of the respondents. In 28 studies it was mentioned that objective assessment (e.g. medical and/or psychological assessment) was additionally taken into account.

The principal method of sample recruitment was via study description in advertisements and/or local or national media (22 studies). The vast majority of the reviewed studies were conducted in Europe (58 studies).

Experimental studies

The major inclusion criteria used by experimental studies to identify individuals with IEI-EMF were:

-

Attribution of NSPS to either various or specific sources of EMF (being reported 13 times).

-

Self-reported IEI-EMF (or synonymous terms) (n = 14).

-

Experience of symptoms during or soon (from 20 minutes to 24 hours) after the individual perception or actual presence or use of an EMF exposure source (n = 10).

-

High score on a symptom scale (n = 6).

In addition, two studies used limitation in daily functioning of the individual due to the attributed health effects as an inclusion criterion.

The main exclusion criterion was the existence of a medical and/or psychiatric or psychological condition that could account for the reported health complaints (n = 20).

Other exclusion criteria included undergoing treatment for somatic or psychiatric conditions (n = 8), pregnancy (n = 5), history of severe injuries (n = 3) and regular smoking (n = 2).

In 16 studies the case definition procedure did not only rely on subjective report, but also on medical and/or psychiatric and/or psychological examination. In eight studies, the sample recruitment was based on participants who were already referred or registered to a health care institution (such as a university hospital) for their health complaints. All extracted data from the experimental studies are presented in Figure 2.

Observational Studies

The major inclusion criteria used by observational studies to identify individuals with IEI-EMF were:

-

Self-reported IEI-EMF (or synonymous terms) (n = 16).

-

Attribution of NSPS to either various or specific EMF sources (n = 12).

-

Experience of symptoms during or soon (from 20 minutes to 24 hours) after the individual perception or actual presence or use of an EMF exposure source (n = 3).

-

Limitation in daily functioning of the individual due to the attributed health effects (n = 2).

The main exclusion criteria were a medical and/or psychiatric or psychological condition that could account for the reported health complaints and undergoing treatment for somatic or psychiatric condition (n = 4).

Eleven studies included medical and/or psychiatric and/or psychological examination to assess whether a pathological condition was responsible for patients’ complaints. In nine studies the sample was based on participants who were already referred or registered to health care institutions for their complaints. All extracted data from the observational studies are listed in Table 3.

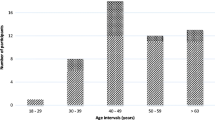

The prevalence of IEI-EMF in randomly selected samples of population-based epidemiological studies varied and seemed to be influenced by the number and degree of strictness of the applied identification criteria. This is illustrated in Figure 3. These differences could also be due to the population under study, year of study and sample stratification (e.g. age range).

Discussion

The present systematic review based on an extensive literature search, summarized the case definition criteria and methods that have been used in the published literature to date for the identification of subjects with IEI-EMF.

It is noteworthy that only 1% of the reviewed studies used the term “IEI-EMF” as a descriptive term, despite the fact that it has been proposed by WHO since 2005 [5]. Sixty-five percent of the studies used the description “Hypersensitivity to EMF” which seems to be mainly characterized by the following aspects: Self-reported sensitivity to one or more sources of EMF, attribution of NSPS to either several or specific EMF sources (such as mobile phones and VDUs), experience of symptoms during or soon after (from 20 minutes to 24 hours) the individual perception or actual presence or use of an EMF source and absence of a (psycho)pathological condition accounting for the reported health complaints. In the majority of the studies the case definition procedure was based exclusively on self-report. In a smaller number of investigations, medical and/or psychiatric and/or psychological assessment was included.

In most of these studies participants were recruited from registries to a health care institution for their symptoms and for whom medical data were available. Although there were no important differences between observational and experimental studies in the most frequently employed criteria, experimental studies used a larger number of criteria per investigation compared to observational studies. Moreover, the demographic profile of the recruited individuals with IEI-EMF in terms of age and gender was quite consistent; the frequency of female gender and age over 40 years were considerably higher in most of the studies.

Despite previous attempts to bring order to this field [6, 53, 70], as it appears in the literature, IEI-EMF is still predominantly a self-reported sensitivity without a widely accepted and validated case definition tool. This could be due to the absence of a bioelectromagnetic mechanism [17] or because of the varying patterns regarding the symptom type, frequency and severity [6, 41]. The other way around could also be the case: The lack of validated case definition criteria could have hindered the identification of homogeneous patient groups and consequently the recognition of symptom profiles and a physiologic mechanism. Furthermore, the application of very broad criteria could dilute the power of the studies and make difficult the detection of those individuals that really suffer from IEI-EMF. For example, although “Attribution” of NSPS to EMF could be considered as a first indication of suffering from IEI-EMF, it is questionable whether it comprises a sufficient identifying criterion when used alone.

Possible subgroups

Several subdivisions may exist within IEI-EMF that may be of relevance to clinicians and researchers.

One such division is that between patients for whom an alternative diagnosis exists, which might account for their symptoms and those for whom it does not. The absence of screening for pathological conditions which might underlie the symptoms reported by participants in many studies was notable. Previous studies have identified occasionally high levels of other diagnoses in such patients, such as somatoform and anxiety disorders which might account for their ill-health [89, 90]. Including these individuals in the same sample as those for whom there is no clear explanation for their symptoms may reduce our ability to identify causal factors for IEI-EMF.

An additional distinction that we may need to take into account is between patients who attribute symptoms to short-term exposure to EMF and those for whom longer-term exposure is relevant. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether generalized and source-specific IEI-EMF should be assessed separately or not. Exposure from far-field sources such as high-voltage overhead powerlines and mobile phone base stations is mostly continuous and people often perceive it as less controllable compared to near-field sources such as mobile phones [10] but there is still no convincing evidence for source-specific sensitivities [13]. As differences may exist between IEI-EMF patients in terms of their psychological and health-related characteristics, division into subgroups for the purposes of research may be of use [22, 23]. Perhaps the most complicated issue is to figure out whether self-reported-NSPS and objectively assessed physiologic reactions are preceded by events of the relevant (EMF) exposures, distinguishable from other random exposure events experienced during the day. Use of a prediction model based on modelled exposure from various sources [91, 92] could be a solution; however it is questionable whether and how it could be systematically incorporated in a case definition tool.

Table 4 illustrates a number of proposed aspects for IEI-EMF, based on a synthesis of the existing identifying criteria in the reviewed literature. Considering the fact that the reported symptoms are quite common in the general population and also the lack of symptom patterns [6, 53] and etiology, the only parameter that clearly distinguishes sensitive from control individuals is the causal attribution of symptomatology to EMF exposure. Therefore, the attribution of health outcomes and self-reported sensitivity to EMF inevitably constitute, at the moment, the cornerstone of IEI-EMF case definition in research and clinical practice. Additional aspects such as medical examination/history would elucidate whether the reported health outcomes can be explained by underlying pathology. Cognitive and behavioral aspects could be complementarily included in the case definition, since evidence on their role in IEI-EMF is promising [18] but not yet established. Moreover, taking into account potentially harmful environmental agents other than EMF would be an important addition for research.

This is the first time that a systematic review is conducted on definitions and identifying criteria for IEI-EMF. Given the large number of included articles, it is unlikely that any missing (or even excluded) studies would alter the results or increase any publication bias, especially since the aim of the current paper was not to assess etiologic associations.

It is a challenge how all the different case definition parameters for IEI-EMF can be concisely embodied in one international operational tool which could be used in research and clinical practice, and how this instrument could be adjusted to the possible cultural differences (e.g. in terms of wording/phrasing questions on health outcomes). Nevertheless, without the harmonization of the conceptual framework and validation of identifying criteria, the value of the case definition standards for IEI-EMF will remain insufficient and possibly unreliable. Apart from research, this has an important impact also in primary care; physicians, who are often the first to be contacted by the sufferers, are usually not adequately informed about IEI-EMF, which can affect the patient-doctor interaction and the management of the patient [26].

In order to properly construct an operational tool, a proposed two-phase approach can be briefly described as follows: In the first phase, a case definition and case selection tool should be developed, taking into account sources such as the published literature, expert opinions (e.g. based on a Delphi procedure [93]) and information on IEI-EMF patient characteristics from available datasets/ongoing research. At this stage, EMF measurements or provocation tests should not be a priority since a provocation study will only have added value after the formulation of a proper case definition and participant selection. Additionally, if the aim of a “case selection tool” is to routinely test cases where symptoms occur without a clear underlying pathology, then that tool should be concise, inexpensive and easy to implement, such as a short questionnaire or checklist. In the second phase, the case definition tool should be validated in terms of practical usability and the ability to differentiate between subgroups of IEI-EMF and patients with other conditions (e.g. chronic fatigue) who report similar symptoms. Based on the findings, the requirements for a follow up study could be outlined.

Conclusions

IEI-EMF is a poorly defined sensitivity. Heterogeneity and ambiguity of the existing definitions and criteria for IEI-EMF show the necessity to develop uniform criteria that will be applicable both in research and clinical practice. Broader criteria identified in the published literature such as attribution of NSPS to EMF and subjective report of being EMF sensitive could be used as a working definition for IEI-EMF which will serve as a basis for the development of a case selection tool. However, further optimization is required, testing its reliability and validity in several different patient groups, leading to an international multidisciplinary protocol with the active involvement of health care providers. This could also be a stepping stone for the harmonization of concepts and case definition for the broader condition of IEI.

Abbreviations

- EMF:

-

Electromagnetic Fields

- EHS:

-

Electrohypersensitivity

- HS:

-

Hypersensitivity

- IEI:

-

Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance

- IEI-EMF:

-

Idiopathic Environmental Intolerance attributed to Electromagnetic Fields

- MP:

-

Mobile Phone(s)

- NSPS:

-

Non-Specific Physical Symptoms

- VDU:

-

Video Display Units

- VDT:

-

Video Display Terminals.

References

Randolph TG: Human ecology and susceptibility to the chemical environment. 1962, Springfield (IL): Charles Thomas

Das-Munshi J, Rubin GJ, Wessely S: Multiple chemical sensitivities: A systematic review of provocation studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006, 118: 1257-1264. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.046.

Reed-Gibson P, Elms ANM, Ruding LA: Perceived Treatment Efficacy for Conventional and Alternative Therapies Reported by Persons with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Environ Health Perspect. 2003, 111: 1498-1504. 10.1289/ehp.5936.

Röösli M, Moser M, Baldinini Y, Meier M, Braun-Fahrländer C: Symptoms of ill health ascribed to electromagnetic field exposure—A questionnaire survey. Int J Hygiene Environ Health. 2004, 207: 141-150. 10.1078/1438-4639-00269.

WHO: Fact Sheet No. 296: Electromagnetic fields and public health. 2005, World Health Organization, http://www.emfandhealth.com/WHO_EMSensitivity.pdf,

Hillert L, Berglind N, Arnetz BB, Bellander T: Prevalence of self-reported hypersensitivity to electric or magnetic fields in a population-based questionnaire survey. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002, 28: 33-41. 10.5271/sjweh.644.

Carlsson F, Karlson B, Orbaek P, Österberg K, Östergren PO: Prevalence of annoyance attributed to electrical equipment and smells in a Swedish population, and relationship with subjective health and daily functioning. Public Health. 2005, 119: 568-577. 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.07.011.

Levallois P, Neutra R, Lee G, Hristova L: Study of self-reported hypersensitivity to electromagnetic fields in California. Environ Health Perspect. 2002, 110: 619-623. 10.1289/ehp.02110s4619.

Schröttner J, Leitgeb N: Sensitivity to electricity - temporal changes in Austria. BMC Publ Health. 2008, 8: 310-10.1186/1471-2458-8-310.

Schreier N, Huss A, Röösli M: The prevalence of symptoms attributed to electromagnetic field exposure: a cross-sectional representative survey in Switzerland. Soz Praventivmed. 2006, 51: 202-209. 10.1007/s00038-006-5061-2.

Tseng MM, Lin YP, Cheng TJ: Prevalence and Psychiatric Co-Morbidity of Self-Reported Electromagnetic Field Sensitivity in Taiwan: A Population-Based Study. Epidemiology. 2008, 19: s108-s109.

Levallois P: Hypersensitivity of human subjects to environmental electric and magnetic field exposure: A review of the literature. Environ Health Perspect. 2002, 110: 613-618.

Rubin GJ, Das-Munshi J, Wessely S: Electromagnetic hypersensitivity: A systematic review of provocation studies. Psychosom Med. 2005, 67: 224-232. 10.1097/01.psy.0000155664.13300.64.

Röösli M: Radiofrequency electromagnetic field exposure and non-specific symptoms of ill health: a systematic review. Environ Res. 2008, 107: 277-287. 10.1016/j.envres.2008.02.003.

Rubin GJ, Nieto-Hernandez R, Wessely S: Idiopathic environmental intolerance attributed to electromagnetic fields (formerly 'electromagnetic hypersensitivity'): An updated systematic review of provocation studies. Bioelectromagnetics. 2009, 31: 1-11.

Röösli M, Frei P, Mohler E, Hug K: Systematic review on the health effects of exposure to radiofrequency electromagnetic fields from mobile phone base stations. Bull World Health Organ. 2010, 88: 887-896. 10.2471/BLT.09.071852.

Rubin GJ, Hillert L, Nieto-Hernandez R, Van Rongen E, Oftedal G: Do people with idiopathic environmental intolerance attributed to electromagnetic fields display physiological effects when exposed to electromagnetic fields? A systematic review of provocation studies. Bioelectromagnetics. 2011, 32: 593-609. 10.1002/bem.20690.

Rubin GJ: Das Munshi J, Wessely S: A systematic review of treatments for electromagnetic hypersensitivity. Psychother Psychosom. 2006, 75: 12-18. 10.1159/000089222.

Österberg K, Persson R, Karlson B, Carlsson EF, Orbaek P: Personality, mental distress, and subjective health complaints among persons with environmental annoyance. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007, 26: 231-241. 10.1177/0960327107070575.

Landgrebe M, Frick U, Hauser S, Langguth B, Rosner R, Hajak G, Eichhammer P: Cognitive and neurobiological alterations in electromagnetic hypersensitive patients: Results of a case–control study. Psychol Med. 2008, 38: 1781-1791. 10.1017/S0033291708003097.

Persson R, Carlsson EF, Österberg K, Orbaek P, Karlson B: A two-week monitoring of self-reported arousal, worry and attribution among persons with annoyance attributed to electrical equipment and smells. Scand J Psychol. 2008, 49: 345-356. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00660.x.

Rubin GJ, Cleare AJ, Wessely S: Psychological factors associated with self-reported sensitivity to mobile phones. J Psychosom Res. 2008, 64: 1-9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.006.

Johansson A, Nordin S, Heiden M, Sandström M: Symptoms, personality traits, and stress in people with mobile phone-related symptoms and electromagnetic hypersensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2010, 68: 37-45. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.06.009.

Baliatsas C, Van Kamp I, Kelfkens G, Schipper M, Bolte J, Yzermans J, Lebret E: Non-specific physical symptoms in relation to actual and perceived proximity to mobile phone base stations and powerlines. BMC Publ Health. 2011, 11: 421-10.1186/1471-2458-11-421.

Huss A, Röösli M: Consultations in primary care for symptoms attributed to electromagnetic fields – a survey among general practitioners. BMC Publ Health. 2006, 6: 267-10.1186/1471-2458-6-267.

Berg-Beckhoff G, Heyer K, Kowall B, Breckenkamp J, Razum O: The views of primary care physicians on health risks from electromagnetic fields. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010, 107: 817-823.

Salomon D: Medical practitioners and electromagnetic fields (EMF): Testing their concern. Comptes Rendus Physique. 2010, 11: 636-640. 10.1016/j.crhy.2011.01.001.

Rea WJ, Pan Y, Fenyves EJ, Sujisawa I, Samadi N, Ross GH: Electromagnetic field sensitivity. J Bioelectricity. 1991, 10: 241-256.

Hamnerius Y, Agrup G, Galt S, Nilsson R, Sandblom J, Lindgren R: Double-blind provocation study of hypersensitivity reactions associated with exposure from VDUs. Preliminary short version. R Swed Acad Sci Rep. 1993, 2: 67-72.

Arnetz BB, Berg M, Anderzen I, Lundeberg T, Haker E: A nonconventional approach to the treatment of ‘environmental illness’. J Occup Environ Med. 1995, 37: 838-844. 10.1097/00043764-199507000-00013.

Andersson B, Berg M, Arnetz BB, Melin L, Langlet I, Liden SA: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of patients suffering from ’electric hypersensitivity’: subjective effects and reactions in a double-blind provocation study. J Occup Environ Med. 1996, 38: 752-758. 10.1097/00043764-199608000-00009.

Bertoft G: Patient reactions to some electromagnetic fields from dental chair and unit: a pilot study. Swed Dent J. 1996, 20: 107-112.

Toomingas A: Provocation of the electromagnetic distress syndrome. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997, 22: 457-458.

Sandström M, Lyskov E, Berglund A, Medvedev S, Hansson-Mild K: Neurophysiological Effects of Flickering Light in Patients with Perceived Electrical Hypersensitivity. J Occup Environ Med. 1997, 39: 15-22. 10.1097/00043764-199701000-00006.

Hillert L, Hedman BK, Dolling BF, Arnetz BB: Cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with electric sensitivity – A multidisciplinary approach in a controlled study. Psychother Psychosom. 1998, 67: 302-310. 10.1159/000012295.

Trimmel M, Schweiger E: Effects of an ELF (50 Hz, 1 mT) electromagnetic field (EMF) on concentration in visual attention, perception and memory including effects of EMF sensitivity. Toxicol Lett. 1998, 96–97: 377-382.

Flodin U, Seneby A, Tegenfeldt C: Provocation of electric hypersensitivity under everyday conditions. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000, 26: 93-98. 10.5271/sjweh.517.

Lonne-Rahm S, Andersson B, Melin L, Schultzberg M, Arnetz B, Berg M: Provocation with stress and electricity of patients with ’sensitivity to electricity. J Occup Environ Med. 2000, 42: 512-516. 10.1097/00043764-200005000-00009.

Hillert L, Kolmodin-Hedman B, Eneroth P, Arnetz BB: The effect of supplementary antioxidant therapy in patients who report hypersensitivity to electricity: a randomized controlled trial. Medscape General Medicine. 2001, 3: 11-

Lyskov E, Sandström M, Hansson-Mild K: Provocation study of persons with perceived electrical hypersensitivity and controls using magnetic field exposure and recording of electrophysiological characteristics. Bioelectromagnetics. 2001, 22: 457-462. 10.1002/bem.73.

Hietanen M, Hamalainen AM, Husman T: Hypersensitivity symptoms associated with exposure to cellular telephones: no causal link. Bioelectromagnetics. 2002, 23: 264-270. 10.1002/bem.10016.

Hillert L, Savlin P, Levy BA, Heidenberg A, Kolmodin-Hedman B: Environmental illness – Effectiveness of a salutogenic group-intervention programme. Scand J Public Health. 2002, 30: 166-175. 10.1080/14034940210133852.

Mueller CH, Krueger H, Schierz C: Project NEMESIS: perception of a 50 Hz electric and magnetic field at low intensities (laboratory experiment). Bioelectromagnetics. 2002, 23: 26-36. 10.1002/bem.95.

Leitgeb N, Schröttner J: Electrosensibility and electromagnetic hypersensitivity. Bioelectromagnetics. 2003, 24: 387-394. 10.1002/bem.10138.

Österberg K, Persson R, Karlson B, Orbæk P: Annoyance and performance in three groups of environmentally intolerant subjects during experimental challenge with chemical odors. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004, 6: 486-496.

Ostergren PO, Merlo J, Lindström M, Rosvall M, Kahn FA, Lithman T: Hälsoförhållanden i Skåne. Folkhälsoenkät Skåne 2000 (Report in Swedish). 2001, Region Skåne: Kommunförbundet Skåne och Skåne läns allmänna Försäkringskassa

Belyaev IY, Hillert L, Protopopova M, Tamm C, Malmgren LOG, Persson BRR, Selivanova G, Harms-Ringdahl M: 915 MHz microwaves and 50 Hz magnetic field affect chromatin conformation and 53BP1 foci in human lymphocytes from hypersensitive and healthy persons. Bioelectromagnetics. 2005, 26: 173-184. 10.1002/bem.20103.

Frick U, Kharraz A, Hauser S, Wiegand R, Rehm J, Von Kovatsits U, Eichhammer P: Comparison perception of singular transcranial magnetic stimuli by subjectively electrosensitive subjects and general population controls. Bioelectromagnetics. 2005, 26: 287-298. 10.1002/bem.20085.

Wenzel F, Reissenweber J, David E: Cutaneous microcirculation is not altered by a weak 50 Hz magnetic field. Biomed Tech. 2005, 50: 14-18.

Regel SJ, Negovetic S, Röösli M, Berdinas V, Schuderer J, Huss A, Lott U, Kuster N, Achermann P: UMTS base stationlike exposure, well-being, and cognitive performance. Environ Health Perspect. 2006, 114: 1270-1275. 10.1289/ehp.8934.

Rubin GJ, Hahn G, Everitt B, Cleare AJ, Wessely S: Are some people sensitive to mobile phone signals? A within participants, double-blind, randomised provocation study. Br Med J. 2006, 332: 886-889. 10.1136/bmj.38765.519850.55.

Eltiti S, Wallace D, Ridgewell A, Zougkou K, Russo R, Sepulveda F, Mirshekar-Syahkal D, Rasor P, Deeble R, Fox E: Does short-term exposure to mobile phone base station signals increase symptoms in individuals who report sensitivity to electromagnetic fields? A double- blind randomized provocation study. Environ Health Perspect. 2007, 115: 1603-1608. 10.1289/ehp.10286.

Eltiti S, Wallace D, Zougkou K, Russo R, Joseph S, Rasor P, Fox E: Development and evaluation of the electromagnetic hypersensitivity questionnaire. Bioelectromagnetics. 2007, 28: 137-151. 10.1002/bem.20279.

Schröttner J, Leitgeb N, Hillert L: Investigation of Electric Current Perception Thershold of Different EHS Groups. Bioelectromagnetics. 2007, 28: 208-213. 10.1002/bem.20294.

Bamiou DE, Ceranic B, Cox R, Watt H, Chadwick P, Luxon LM: Mobile telephone use effects on peripheral audiovestibular function: A case- control study. Bioelectromagnetics. 2008, 29: 108-117. 10.1002/bem.20369.

Hillert L, Akerstedt T, Lowden A, Wiholm C, Kuster N, Ebert S, Boutry C, Moffat SD, Berg M, Arnetz BB: The effects of 884 MHz GSM wireless communication signals on headache and other symptoms: An experimental provocation study. Bioelectromagnetics. 2008, 29: 185-196. 10.1002/bem.20379.

Kwon MS, Koivisto M, Laine M, Hamalainen H: Perception of the electromagnetic field emitted by a mobile phone. Bioelectromagnetics. 2008, 29: 154-159. 10.1002/bem.20375.

Landgrebe M, Barta W, Rosengarth K, Frick U, Hauser S, Langguth B, Rutschmann R, Greenlee MW, Hajak G, Eichhammer P: Neuronal correlates of symptom formation in functional somatic syndromes: A fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2008, 41: 1336-1344. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.171.

Frick U, Mayer M, Hauser S, Binder H, Rosner R, Eichhammer P: Entwicklung eines deutschsprachigen Messinstruments für “Elektrosmog-Beschwerden” (in German). Umweltmedizin in Forschung & Praxis. 2006, 11: 11-22.

Leitgeb N, Schröttner J, Cech R, Kerbl R: EMF-protection sleep study near mobile phone base stations. Somnologie. 2008, 12: 234-243. 10.1007/s11818-008-0353-9.

Fahrenberg J: Die Freiburger Beschwerdenliste (FBL) (in German). Z Klin Psychol. 1975, 4: 79-100.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28: 193-213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4.

Augner C, Florian M, Pauser G, Oberfeld G, Hacker GW: GSM base stations: Short-term effects on well-being. Bioelectromagnetics. 2009, 30: 73-80. 10.1002/bem.20447.

Furubayashi T, Ushiyama A, Terao Y, Mizuno Y, Shirasawa K, Pongpaibool P, Simba AY, Wake K, Nishikawa M, Miyawaki K, Yasuda A, Uchiyama M, Yamashita HK, Masuda H, Hirota S, Takahashi M, Okano T, Inomata-Terada S, Sokejima S, Maruyama E, Watanabe S, Taki M, Ohkubo C, Ugawa Y: Effects of short-term W-CDMA mobile phone base station exposure on women with or without mobile phone related symptoms. Bioelectromagnetics. 2009, 30: 100-113. 10.1002/bem.20446.

Nam KC, Lee JH, Noh HW, Cha EJ, Kim NH, Kim DW: Hypersensitivity to RF fields emitted from CDMA cellular phones: A provocation study. Bioelectromagnetics. 2009, 30: 641-650. 10.1002/bem.20518.

Szemerszky R, Koteles F, Lihi R, Bardos G: Polluted places or polluted minds? An experimental sham-exposure study on background psychological factors of symptom formation in ‘Idiophatic Environmental Intolerance attributed to electromagnetic fields’. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2010, 213: 387-394. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.05.001.

Nieto-Hernandez R, Williams J, Cleare AJ, Landau S, Wessely S, Rubin GJ: Can exposure to a terrestrial trunked radio (TETRA)-like signal cause symptoms? A randomized double-blind provocation study. Occup Environ Med. 2011, 68: 339-344. 10.1136/oem.2010.055889.

Bergdahl J, Tillberg A, Stenman E: Odontologic survey of referred patients with symptoms allegedly caused by electricity or visual display units. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998, 56: 303-307. 10.1080/000163598428491.

Hocking B: Preliminary report: symptoms associated with mobile phone use. Occup Med. 1998, 48: 357-360. 10.1093/occmed/48.6.357.

Hillert L, Hedman BK, Söderman E, Arnetz BB: Hypersensitivity to electricity: Working definition and additional characterization of the syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1999, 47: 429-438. 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00048-3.

Stockenius S, Brugger P: Perceived electrosensitivity and magical ideation. Percept Mot Skills. 2000, 90: 899-900. 10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.899.

Bergdahl J, Bergdahl M: Environmental illness: evaluation of salivary flow, symptoms, diseases, medications, and psychological factors. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001, 59: 104-110. 10.1080/000163501750157270.

Hillert L, Flato S, Georgellis A, Arnetz BB, Kolmodin-Hedman B: Environmental illness: Fatigue and cholinesterase activity in patients reporting hypersensitivity to electricity. Environ Res. 2001, 85: 200-206. 10.1006/enrs.2000.4225.

Lyskov E, Sandström M: Hansson Mild K: Neurophysiological study of patients with perceived electrical hypersensitivity. Int J Psychophysiol. 2001, 42: 233-241. 10.1016/S0167-8760(01)00141-6.

Stenberg B, Bergdahl J, Edvardsson B, Eriksson N, Lindén G, Widman L: Medical and social prognosis for patients with perceived hypersensitivity to electricity and skin symptoms related to the use of visual display terminals. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002, 28: 349-357. 10.5271/sjweh.685.

Sandström M, Lyskov E, Hörnsten R: Hansson-Mild, Wiklund U, Rask P, Klucharev V, Stenberg B, Bjerle P: ECG monitoring in patients with perceived electrical hypersensitivity. Int J Psychophysiol. 2003, 49: 227-235. 10.1016/S0167-8760(03)00145-4.

Bergdahl J, Stenberg B, Eriksson N, Lindén G, Widman L: Coping and self-image in patients with visual display terminal-related skin symptoms andperceived hypersensitivity to electricity. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004, 77: 538-542. 10.1007/s00420-004-0546-x.

Bergdahl J, Marell L, Bergdahl M, Perris H: Psychobiological personality dimensions in two environmental-illness patient groups. Clin Oral Investig. 2005, 9: 251-256. 10.1007/s00784-005-0015-2.

Eriksson NM, Stenberg BG: Baseline prevalence of symptoms related to indoor environment. Scand J Public Health. 2006, 34: 387-396. 10.1080/14034940500228281.

Schüz J, Petters C, Egle UT, Jansen B, Kimbel R, Letzel S, Nix W, Schmidt LG, Vollrath L: The “Mainzer EMF-Wachhund”: results from a watchdog project on self-reported health complaints attributed to exposure to electromagnetic fields. Bioelectromagnetics. 2006, 27: 280-287. 10.1002/bem.20212.

Landgrebe M, Hauser S, Langguth B, Frick U, Hajak G, Eichhammer P: Altered cortical excitability in subjectively electrosensitive patients: results of a pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2007, 62: 283-288. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.11.007.

Hardell L, Carlberg M, Söderqvist F, Hardell K, Björnfoth H, van Bavel B, Lindström G: Increased concentrations of certain persistent organic pollutants in subjects with self-reported electromagnetic hypersensitivity–a pilot study. Electromagn Biol Med. 2008, 27: 197-203. 10.1080/15368370802089053.

Lidmark AM, Wikmans T: Are they really sick? A report on persons who are electrosensitive and/or injured by dental material in Sweden. Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 2008, 23: 153-160.

Dahmen N, Ghezel-Ahmadi D, Engel A: Blood Laboratory Findings in Patients Suffering From Self-Perceived Electromagnetic Hypersensitivity (EHS). Bioelectromagnetics. 2009, 30: 299-306. 10.1002/bem.20486.

Frick U, Rehm J, Eichhammer P: Risk perception, somatization, and self report of complaints related to electromagnetic fields—a randomized survey study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2002, 205: 353-360. 10.1078/1438-4639-00170.

Mohler E, Frei P, Fahrländer CB, Fröhlich J, Neubauer G, Röösli M: Effects of Everyday Radiofrequency Electromagnetic-Field Exposure on Sleep Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study. Radiat Res. 2010, 174: 347-356. 10.1667/RR2153.1.

Nordin M, Andersson L, Nordin S: Coping strategies, social support and responsibility in chemical Intolerance. J Clin Nurs. 2010, 19: 2162-2173. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03264.x.

Röösli M, Mohler E, Frei P: Sense and sensibility in the context of radiofrequency electromagnetic field exposure. Comptes Rendus Physique. 2010, 11: 576-584. 10.1016/j.crhy.2010.10.007.

Bornschein S, Hausteiner C, Zilker T, Förstl H: Psychiatric and somatic disorders and multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) in 264 environmental patients. Psychol Med. 2002, 32: 1387-1394.

Bailer J, Witthöft M, Paul C, Bayerl C, Rist F: Evidence for overlap between idiopathic environmental intolerance and somatoform disorders. Psychosom Med. 2005, 67: 921-929. 10.1097/01.psy.0000174170.66109.b7.

Frei P, Mohler E, Bürgi A, Fröhlich J, Neubauer G, Braun-Fahrländer C, Röösli M: A prediction model for personal radio frequency electromagnetic field exposure. Sc of the Tot Env. 2009, 408: 102-108. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.09.023.

Frei P, Mohler E, Bürgi A, Fröhlich J, Neubauer G, Braun-Fahrländer C, Röösli M: Classification of personal exposure to radio frequency electromagnetic fields (RF-EMF) for epidemiological research: Evaluation of different exposure assessment methods. Environ Int. 2010, 36: 714-720. 10.1016/j.envint.2010.05.005.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H: Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000, 32: 1008-1015.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/643/prepub

Acknowledgements

The current study is part of the project INCORPORATE “International collaboration on symptoms, psychological aspects and EMF exposure estimates: Towards harmonization and validation”, funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). The study sponsor had no involvement in study design, writing and interpretation of the results and in the decision to submit the study for publication. The authors would like to thank Dr Rosa Nieto-Hernandez for her help in structuring the literature search protocol and Dr Rik Bogers for his feedback on the paper. In addition, the authors would like to thank Dr Joris Yzermans and Dr Mariette Hooiveld for their ideas regarding the suggestions for the development of a screening tool for IEI-EMF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

GJR has previously been funded by the UK Mobile Telecommunications and Health Research programme (http://www.MTHR.org.uk) and has acted as an expert witness for the Diocese of Norwich relating to the installation of Wifi on Church property. EL chairs the Science Forum of the Dutch Expertise Platform for Electromagnetic Fields (http://www.kennisplatform.nl/).

Authors’ contributions

All the authors participate in the international multidisciplinary project INCORPORATE of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). CB carried out the literature search, drafted the manuscript and incorporated input from all the rest authors in the manuscript. IVK and GJR conceived and coordinated the study and provided critical comments on the manuscript. EL provided critical comments on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Baliatsas, C., Van Kamp, I., Lebret, E. et al. Idiopathic environmental intolerance attributed to electromagnetic fields (IEI-EMF): A systematic review of identifying criteria. BMC Public Health 12, 643 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-643

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-643