Abstract

Background

Very few studies have evaluated the association between a child's lifestyle factors and their parent's ability to recognise the overweight status of their offspring. The aim of this study was to analyze the factors associated with a parent's ability to recognise their own offspring's overweight status.

Methods

125 overweight children out of all 1,278 school beginners in Northern Finland were enrolled.

Weight and height were measured in health care clinics. Overweight status was defined by BMI according to internationally accepted criteria. A questionnaire to be filled in by parents was delivered by the school nurses. The parents were asked to evaluate their offspring's weight status. The child's eating habits and physical activity patterns were also enquired about. Factor groups of food and physical activity habits were formed by factor analysis. Binary logistic regression was performed using all variables associated with recognition of overweight status in univariate analyses. The significant risk factors in the final model are reported using odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Fifty-seven percent (69/120) of the parents of the overweight children considered their child as normal weight. Child's BMI was positively associated with parental recognition of overweight (OR 3.59, CI 1.8 to 7.0). Overweight boys were less likely to be recognised than overweight girls (OR 0.14, CI 0.033 to 0.58). Child's healthy diet (OR 0.22, CI 0.091 to 0.54) and high physical activity (OR 0.29, CI 0.11 to 0.79) were inversely related to parental recognition of overweight status.

Conclusions

Child's healthy eating habits and physical activity are inversely related to parental recognition of their offspring's overweight. These should be taken into account when planning prevention and treatment strategies for childhood obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parents who do not recognise the weight status of their own overweight children may be less likely to provide them support in order to achieve a healthy weight. However, a large proportion of parents do not recognise that their offspring is in fact overweight or obese [1–8]. According to a recent review less than 50% of parents successfully recognised their offspring's overweight status [1]. Parental recognition of child's overweight is important in order to implement prevention and treatment strategies early in life.

In previous studies involving a broad age range of children, parents of older children have been more likely to identify their child as overweight than parents of younger children [3, 9]. In many studies, mothers have been more likely to identify their daughters as being overweight than their sons [9–13], but several studies have supported parental perception is not associated with the a child's gender [3, 14–20]. Maternal weight status or a mother's awareness of her own overweight status seems not to be associated with awareness of her offspring's weight status [10, 12, 13, 16, 21]. However, mothers with lower BMI have been suggested to report their child as overweight more often than mother's with high BMI [9] but contradictory evidence also exits [19]. Previous studies have also revealed the positive relationship between maternal education and the ability to recognise a child's overweight status [13, 15, 22].

Few studies have evaluated the association between child's diet, physical activity and parent's ability to recognise their offspring's overweight status [3, 21–23]. Small qualitative studies in pre-school aged children has reported findings that a child who has a healthy diet, is happy, active, and can accomplish normal childhood activities was not considered as being overweight, regardless of the child's BMI [21, 23]. In a study by Eckstein, parents of overweight children were more likely to be concerned if they recognised their child as being inactive [3]. In opposition to these findings, Manios et al found that the likelihood of mothers' underestimation of their preschool aged child's weight status was significantly higher in children engaging in physical activity for less than 3 h/week [22].

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the association between sosiodemographic and lifestyle factors and parents' ability to recognise overweight status in their own seven year old children in Finland.

Methods

Subjects

In this cross sectional study all school beginners (born in 1997, n = 1278) in the city of Oulu were invited to participate in the study by school nurses in November 2004. The children were given an anonymous questionnaire to be filled in by their parents. Parents were informed about the objectives of the work and the voluntary nature of their and their children's participation in the survey. The research carried out was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Oulu University Hospital.

The parents were asked to collect and record their child's weight history from birth to current age from the health records. Weight (in underwear) and height (without shoes) was subsequently measured by a qualified nurse in health care clinic. Overweight status was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th centile, and obesity as a BMI ≥ 95th centile relative to reference data for the international population [24]. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2).

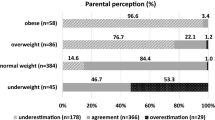

The outcome: parent's perception of her offspring's weight status

The parents were asked to rate their child's level of weight status using the statements: 'my child is underweight', 'normal weight', 'slightly overweight' and 'heavily overweight'. The parents classified their child as "underweight or normal weight" (BMI < 85th centile), slightly or heavily overweight (BMI > = 95th centile) or heavily overweight (BMI > = 95th centile). These categories were finally defined as "normal", "overweight" and "obese". The parents' ratings were compared to the child's correct weight status.

Information on the family

Information on the parents' marital status, educational level, age and lifestyle factors such as smoking were asked. Occurrences of certain chronic diseases like diabetes, heart diseases, asthma and rheumatoid disease in the family were also asked. The parents' own weight and height were asked, as well as the parents' perception of their own weight status. The parent's overweight was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2.

Physical activity and dietary patterns

Physical activity was assessed via a series of questions adapted from an Activity Questionnaire [25]. The number of hours spent in physical and sedentary activities during a usual week (playing, exercise, watching television, working on a computer, playing video games and reading) was asked. The parents were also asked to report the frequency of exercise sessions they had together with their child using the statements: 'seldom or never', 'sometimes', 'often'. Parents' perception of their children's physical activity level was asked: 'In your opinion, is this child as physical active as she/he should be?' The alternatives were 'no, she/he is not', 'yes, she/he is' and 'she/he is too active'.

There were questions about meal patterns, eating habits and food frequencies. The food frequency questionnaire has been developed by the National Public Health Institute and has been used since 1978 [26]. The questionnaire consisted of twenty-two questions on the inclusion of the typical foods eaten by Finnish children (for example porridge or muesli, cereals, pizza, hamburgers, milk, milk chocolate, yoghurt or pudding, cheese, sausages, ham, cookies and cakes, bun, berries, fruit, fresh vegetables, chocolate, candies, juice, light soft drink, sugared soft drink, chips). The food consumption frequencies were: many times per day, daily or almost daily, 3 to 5 times per week, 1 to 2 times per week and less than two times per week. A child's overeating was assessed by the question 'How often do you estimate that your child overeats?' using the statements: 'Never', 'Once a week', 'A few times per week' and 'Many times per day'. A child's appetite was also considered with the following: 'Which one of the next alternatives best describes your child's appetite?' The alternatives were 'very good appetite', 'good appetite', moderate appetite', 'poor appetite' and 'very poor appetite'.

Statistical analysis

The data gathered was analysed with SPSS for Windows software, version 15.0.1. The analyses were performed using all available data without replacement of missing values. The association between explanatory factors and the recognition of a child's overweight status was first analysed using cross-tabulation and χ 2-test for the dichotomous variables and independent t-test for continuous variables.

Factor groups of food and physical activity habits were formed by factor analysis. When lifestyle factors were formed, the numbers of factors to be retained for the description of lifestyle patterns were determined by components with eigenvalue > 1 and examination of the scree plots. Eating and physical activity patterns were identified by principal component with varimax (orthogonal) rotation to identify non-correlated factors. Items with factor loadings ≥ 0.3 were used to calculate factor scores for each of the factors.

To assess how well the various background and lifestyle factors were able to explain the parents' recognition of a child's overweight status, multivariate logistic regression with enter method analysis was performed using all variables associated with the recognition of overweight status in univariate analyses. The significant risk factors in the final model are reported using odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was achieved when p < 0.05.

Results

Of the 1278 children invited to participate, 855 (77%) returned the completed questionnaire. Eighty-five percent of questionnaires were filled by mothers, 12% by fathers and one percent by another caregiver or guardian. Measures for height and weight at seven years of age were available for 749 (59%) of the children (382 boys, 367 girls).

17% (125/749) of the children were classified overweight or obese according to the international criteria, while 8% (58/728) of the children were classified as overweight and 0.3% obese (2/728) by the parents. Over half (69/120) of the parents of the overweight (including obese) children and 18% (6/33) of the parents of obese children considered their children as normal weight. A small number of parents (9/607) believed their normal weight children were overweight. The parents of overweight daughters (n = 63) were more likely to accurately identify the weight status of their child than the parents of overweight sons (n = 57) (51% vs. 33%, p = 0.053).

A third (219/717) of the mothers and over half (352/645) of the fathers were classified as being overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25). Of the overweight and obese mothers 8% (18/219) considered themselves as being of normal weight as did 45% (158/352) of the overweight and obese fathers. 13% (63/498) of the normal weight mothers and 3% (9/293) of the normal weight fathers considered themselves as overweight.

Factors associated with the recognition of a child's overweight status

The parents' ability to recognize their child's overweight status was positively associated with the child's BMI, mother's age and father's body mass index. There was a negative relationship between the child's age and correct rating (table 1). The accuracy of the parents' perception of their child's weight status was not associated with the accuracy of perception on the parents' own weight status. The children, whose overweight status was recognised by their parents, had less close relatives with heart disease (table 1). A married parent was less likely to recognise her child's overweight status than a parent who was divorced, widowed or unmarried (table 1).

Lifestyle patterns associated with recognition of child's overweight status

The variables associated with the parents' perception of the child's overweight status in univariate analysis were 'How often does your child eat porridge or muesli?', 'How often does your child eat fruits?', 'How often does your child eat berries or food made of berries?', 'How often does your child eat too much?', How would you describe your child's appetite?', 'How often do parents exercise together with their child?' and 'How active is your child?' (table 2).

Three lifestyle factor solutions were identified. Factor 1 showed a "Healthy diet" pattern with high levels of fruits, berries and porridge in the child's diet. An "Eating too much" pattern was seen in factor 2 (a child has good appetite and eats too much) whereas the third factor showed a "Physically active" pattern with an active child exercising frequently with her parents. Factor 1 was the dominant lifestyle pattern and explained 16.0% of the variance of the response variables, and the remaining factors explained 12.8% and 8.8% of the variance, respectively. Together, the three factors explained 37.6% of the variance.

'Healthy diet' and 'Physically active' factor scores were lower in the group 'child's overweight status is recognised by parent' than in the group 'child's overweight status is not recognised' (-0,27 (SD 0.78) vs. 0.19 (SD 0.96), p = 0.006 and -0,29 (SD 0.86) vs. 0.19 (SD 0.45), p = 0.001 respectively). 'Eating too much' factor scores were higher in the group 'child's overweight status is recognised by parent' than in group 'child's overweight status is not recognised' (0.25 (SD 0.81) vs. -0.22 (SD 0.78), p = 0.002).

Factors associated with identification of a child's overweight status in multivariate analysis

The results of binary logistic regression analyses for the perception of child's weight status are presented in table 3. Child's BMI was positively associated with parental recognition of overweight. Overweight status was identified more frequently in girls than in boys. A child's healthy diet and high physical activity were inversely related with parental recognition of overweight status in multivariate analysis. The model explained 71% of the variance (Nagelkerke R square).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, more than half of the parents' with an overweight or obese seven year old child did not recognise their child's overweight status. Daughters' overweight status was identified better than sons, and physically active children with healthy eating habits had lower probability for parental identification of overweight status.

The low rate of overweight recognition in our study is comparable with previous studies [1–8]. It seems that overweight children must be obese in order to be recognized as overweight [19]. Also in our study, the higher the child's BMI was, the better the overweight was identified, although even 18% of the parents of obese children considered their children as normal weight. It is not fully understood why parents so easily mistake their child's weight as being normal in cases where the child is overweight. Jain et al. reported that overweight children were described as "thick" or "big boned" by their mainly overweight mothers [21]. In a study of Adams et al, Native-American big children were viewed more positively as "cute and healthy," whereas "skinny" (i.e., normal weight) children were viewed more negatively as "underfed and sickly" [19]. Also they reported that some parents had experienced social pressure to "fatten up" their babies. We had no data on possible social factors underlying poor recognition of child's overweight for which an explanation remains to be found in future studies.

Children with healthy diet or high physical activity were classified as overweight less frequently by their parents than physically inactive children or children with poor eating habits. Our results are in agreement with some previous studies [3, 21, 23] but opposite findings also exist [22]. Manios et al found that mothers whose children were more physically active were less likely to underestimate their child's weight status [22]. Comparison of studies is difficult because of the varying age and ethnic and social background of the study populations and differences in methods used. 'Eating too much'-factor and heart diseases in the family were also associated with the perception of child's overweight status. However, the associations were not statistically significant.

We did not ask if the parents who recognised their child's overweight status were worried about their child's weight. According to the previous studies, parents are not always worried about their offspring's weight or health despite the offspring's overweight status [15, 17–19, 27], especially if a child has a healthy appetite and eats healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables [21]. Should parents be aware and worried of a child's overweight status, if the child is physically active and has healthy eating habits? According to a recent review, the risks of obesity is greater than those from being sedentary, i.e., high physical activity reduces, but does not totally offset risks related to obesity [28]. The parental awareness of a child's obesity should be promoted, remembering at the same time, physical activity is highly recommended and should be encouraged, especially in overweight and obese children [29].

In opposition to the previous findings which revealed that mothers with lower educational levels are more likely to misclassify their children's weight status [13, 15, 22], we did not find any association between parental education level and the recognition of childhood overweight status. In our study, about 70% of the mothers had high education which may have affected the results.

Like many other studies, we found that overweight girls were more frequently identified as overweight by their parent's than boys [9–13]. In our study, mothers recognised their own overweight status better compared to the fathers, which has also been observed in previous studies [30–32]. A relatively small proportion (8%) of overweight mothers considered themselves being normal weight compared to previous studies, where 20-40% of overweight women failed to perceive their weight as being too high [33, 34]. This may be a result from high education level of mothers in our study. High educated women have been shown to consider themselves as overweight more often than low educated women [31, 33]. Many studies have reported that women and adolescent girls more often try to lose weight than boys [35, 36], and they are more likely than men to be dissatisfied with their body image and size [37], which reflect that Western culture particularly pressures women to be of normal weight or even slim. The fact that parents identify their daughters overweight status better than their sons may also reflect this cultural phenomenon.

This study does have some limitations. Questionnaires were predominantly filled in by mothers, and the classification of the child's weight status was mainly based upon their mother's impression. Physical activity levels were not measured objectively, and we had no information on energy intake or portion sizes. The use of accelerometer or food diaries would have provided more valid data. However, questionnaires are common, low-cost methods particularly in large epidemiological studies. Data on parental height and weight were based on self-reports. In our data, 30% of mothers were classified as overweight. According to previous reports, prevalence of overweight has been reported to be 55% in women aged 35-44 years in North-Finland [38]. Thus, the mothers in our study seem to have underestimated their weight.

Conclusions

Most parents with an overweight or obese seven year old child seem not to recognise their child's overweight status, especially if the child is physically active and has healthy eating habits. This should be taken into account when planning interventions and educating health care personnel. Healthcare providers should promote awareness of childhood obesity among community.

References

Parry LL, Netuveli G, Parry J, Saxena S: A systematic review of parental perception of overweight status in children. J Ambul Care Manage. 2008, 31: 253-268.

Chaimovitz R, Issenman R, Moffat T, Persad R: Body perception: do parents, their children, and their children's physicians perceive body image differently?. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008, 47: 76-80. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815a34.

Eckstein KC, Mikhail LM, Ariza AJ, Thomson JS, Millard SC, Binns HJ: Parents' perceptions of their child's weight and health. Pediatrics. 2006, 117: 681-690. 10.1542/peds.2005-0910.

Hackie M, Bowles CL: Maternal perception of their overweight children. Public Health Nurs. 2007, 24: 538-546. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00666.x.

He M, Evans A: Are parents aware that their children are overweight or obese? Do they care?. Can Fam Physician. 2007, 53: 1493-1499.

Killion L, Hughes SO, Wendt JC, Pease D, Nicklas TA: Minority mothers' perceptions of children's body size. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006, 1: 96-102. 10.1080/17477160600684286.

Muhammad NA, Omar K, Shah SA, Muthupalaniappen LA, Arshad F: Parental perception of their children's weight status, and its association with their nutrition and obesity knowledge. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008, 17: 597-602.

Vuorela N, Saha MT, Salo MK: Parents underestimate their child's overweight. Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99: 1374-1379. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01829.x.

Maynard LM, Galuska DA, Blanck HM, Serdula MK: Maternal perceptions of weight status of children. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: 1226-1231.

Boutelle K, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M: Mothers' perceptions of their adolescents' weight status: are they accurate?. Obes Res. 2004, 12: 1754-1757. 10.1038/oby.2004.217.

Fisher L, Fraser J, Alexander C: Caregivers' inability to identify childhood adiposity: a cross-sectional survey of rural children and their caregivers' attitudes. Aust J Rural Health. 2006, 14: 56-61. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00764.x.

Jeffery AN, Voss LD, Metcalf BS, Alba S, Wilkin TJ: Parents' awareness of overweight in themselves and their children: cross sectional study within a cohort (EarlyBird 21). BMJ. 2005, 330: 23-24. 10.1136/bmj.38315.451539.F7.

Baughcum AE, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC: Maternal perceptions of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics. 2000, 106: 1380-1386. 10.1542/peds.106.6.1380.

Carnell S, Edwards C, Croker H, Boniface D, Wardle J: Parental perceptions of overweight in 3-5 y olds. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005, 29: 353-355. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802889.

Genovesi S, Giussani M, Faini A, Vigorita F, Pieruzzi F, Strepparava MG, Stella A, Valsecchi MG: Maternal perception of excess weight in children: a survey conducted by paediatricians in the province of Milan. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94: 747-752. 10.1080/08035250510028894.

Jackson J, Strauss CC, Lee AA, Hunter K: Parents' accuracy in estimating child weight status. Addict Behav. 1990, 15: 65-68. 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90007-K.

Young-Hyman D, Herman LJ, Scott DL, Schlundt DG: Care giver perception of children's obesity-related health risk: a study of African American families. Obes Res. 2000, 8: 241-248. 10.1038/oby.2000.28.

Rich SS, DiMarco NM, Huettig C, Essery EV, Andersson E, Sanborn CF: Perceptions of health status and play activities in parents of overweight Hispanic toddlers and preschoolers. Fam Community Health. 2005, 28: 130-141.

Adams AK, Quinn RA, Prince RJ: Low recognition of childhood overweight and disease risk among Native-American caregivers. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 146-152. 10.1038/oby.2005.19.

Rhee KE, De Lago CW, rscott-Mills T, Mehta SD, Davis RK: Factors associated with parental readiness to make changes for overweight children. Pediatrics. 2005, 116: e94-101. 10.1542/peds.2004-2479.

Jain A, Sherman SN, Chamberlin LA, Carter Y, Powers SW, Whitaker RC: Why don't low-income mothers worry about their preschoolers being overweight?. Pediatrics. 2001, 107: 1138-1146. 10.1542/peds.107.5.1138.

Manios Y, Kondaki K, Kourlaba G, Vasilopoulou E, Grammatikaki E: Maternal perceptions of their child's weight status: the GENESIS study. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12: 1099-1105. 10.1017/S1368980008004412.

Reifsnider E, Flores-Vela AR, Beckman-Mendez D, Nguyen H, Keller C, Dowdall-Smith S: Perceptions of children's body sizes among mothers living on the Texas-Mexico border (La Frontera). Public Health Nurs. 2006, 23: 488-495. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00588.x.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH: Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000, 320: 1240-1243. 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240.

Bar-Or O: Children and Exercise in a clinical contest- an overview. Pediatric Sports Medicine for the Practitioner. 1983, New York: Springer-Verlag, 66-87.

Helakorpi S, Berg M-A, Uutela A, Puska P: Health Behaviour among Finnish Adult Population, Spring 1995. 1995, Helsinki

Holm-Denoma JM, Lewinsohn PM, Gau JM, Joiner TE, Striegel-Moore R, Otamendi A: Parents' reports of the body shape and feeding habits of 36-month-old children: an investigation of gender differences. Int J Eat Disord. 2005, 38: 228-235. 10.1002/eat.20180.

Fogelholm M: How physical activity can work?. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008, 3 (Suppl 1): 10-14.

Brambilla P, Pozzobon G, Pietrobelli A: Physical activity as the main therapeutic tool for metabolic syndrome in childhood. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010

Bish CL, Michels BH, Maynard LM, Serdula MK, Thompson NJ, Kettel KL: Health-related quality of life and weight loss among overweight and obese U.S. adults, 2001 to 2002. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006, 14: 2042-2053. 10.1038/oby.2006.239.

Chang VW, Christakis NA: Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2003, 24: 332-339. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00020-5.

Schieman S, Pudrovska T, Eccles R: Perceptions of body weight among older adults: analyses of the intersection of gender, race, and socioeconomic status. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007, 62: S415-S423.

Alwan H, Viswanathan B, Williams J, Paccaud F, Bovet P: Association between weight perception and socioeconomic status among adults in the Seychelles. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 467-10.1186/1471-2458-10-467.

Blokstra A, Burns CM, Seidell JC: Perception of weight status and dieting behaviour in Dutch men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999, 23: 7-17. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800803.

Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Khan LK, Serdula MK: Weight-control practices among U.S. adults, 2001-2002. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31: 18-24. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.016.

Ojala K, Vereecken C, Valimaa R, Currie C, Villberg J, Tynjala J, Kannas L: Attempts to lose weight among overweight and non-overweight adolescents: a cross-national survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007, 4: 50-10.1186/1479-5868-4-50.

Strauss RS: Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999, 153: 741-747.

Helakorpi S, Patja K, Prättälä R, Uutela A: Health Behaviour and Health among the Finnish Adult Population, Spring 2006. 2007

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/665/prepub

Acknowledgements and funding

This study was supported by the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, the Juho Vainio Foundation and the Ministry of Education in Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The authors' responsibilities were as follows--MLV, RIK, KMK, SMK-K, JHL: designed the study; MLV: analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors: provided advice and consultation and reviewed the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vanhala, M.L., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.M., Kaikkonen, K.M. et al. Factors associated with parental recognition of a child's overweight status - a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 11, 665 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-665

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-665