Abstract

Background

Self-reported health status in underserved population of prisoners has not been extensively explored. The purposes of this cross-sectional study were to assess self-reported health, quality of life, and access to health services in a sample of male prisoners of Italy.

Methods

A total of 908 prisoners received a self-administered anonymous questionnaire pertaining on demographic and detention characteristics, self-reported health status and quality of life, access to health services, lifestyles, and participation to preventive, social, and rehabilitation programs. A total of 650 prisoners agreed to participate in the study and returned the questionnaire.

Results

Respectively, 31.6% and 43.5% of prisoners reported a poor perceived health status and a poor quality of life, and 60% admitted that their health was worsened or greatly worsened during the prison stay. Older age, lower education, psychiatric disorders, self-reported health problems on prison entry, and suicide attempts within prison were significantly associated with a perceived worse health status. At the time of the questionnaire delivery, 30% of the prisoners self-reported a health problem present on prison entry and 82% present at the time of the survey. Most frequently reported health problems included dental health problems, arthritis or joint pain, eye problems, gastrointestinal diseases, emotional problems, and high blood pressure. On average, prisoners encountered general practitioners six times during the previous year, and the frequency of medical encounters was significantly associated with older age, sentenced prisoners, psychiatric disorders, and self-reported health problems on prison entry.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that prisoners have a perceived poor health status, specific care needs and health promotion programs are seldom offered. Programs for correction of risk behaviour and prevention of long-term effects of incarceration on prisoners' health are strongly needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prisoners' health represent one of the major challenge for public health and they have often the greatest needs since poor socio-economic conditions are associated with multiple health risks and greater morbidity and mortality [1–3]. Thus, prisoners tend to show high morbidity rate at admission, especially for chronic diseases, mental illnesses, infectious diseases, and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) [4–8]. These highly vulnerable individuals have generally poor access to health services outside the prison and, once entered into penitentiary centres, most of them will return in the community after a short period of detention [9]. Hence, the prison may represent an opportunity to assist public health in a cost-effective manner, that benefits the society at whole, through prevention and treatment of diseases and correction of risk behaviours in this subgroup [9]. For instance, it has been established that prisoners are at increased risk of death after release from prison, mainly in the first two weeks, and important risk factors that former prisoners face are drug overdose, cardiovascular disease, homicide, and suicide [10–12]. The provision of specific interventions aimed at risk reduction while prisoners are in custody may prevent the high rate of recidivism and morbidity and could facilitate their adjustment in the community [10, 11, 13].

Self-rated health is commonly reported as a subjective indicator, as a strong predictor of longer-term morbidity and mortality, and as a method to identify high-risk groups with health needs [14, 15]. Studies assessing self-rated health and chronic conditions in prisoners showed a perceived poor health status and high morbidity, especially in comparison with the general population [2, 8, 9, 16]. Since similar research has not been conducted in Italy, this survey was carried out with the aims of assessing their self-rated health, the utilization of prisons health services, and the role of demographic and selected characteristics related to imprisonment status on the outcomes of interest among a sample of prisoners in Italy.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between February and December 2005 in Calabria, South of Italy, through a self-administered questionnaire on a population of male prisoners. Out of the 10 penal institutions located in the area, that can take into custody 2,347 prisoners [17], four institutions, for 1,085 potential participants including 463 in Catanzaro, 242 in Vibo Valentia, 209 in Rossano, and 171 in Castrovillari, were randomly selected. The whole prisoner population able to read Italian from the selected institutions was invited to participate. A total of 908 prisoners, 83.7% of the total eligible population, were enrolled in the study. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and prisoners' answers were anonymous and confidential.

A pretest was carried out on a convenience sample of 30 prisoners from the target population, in order to evaluate clarity, comprehensiveness, and acceptability of the questionnaire [18]. Feedback was incorporated into the questionnaire prior to the initial delivering.

In order to increase the participation, Prisons Medical Officers, who had been previously trained, were involved in handing out and in collecting self-administered questionnaires and were advised to respond to prisoners' queries only about the procedure and to guarantee the independent completion of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire included an introduction aimed at detailing the objectives of the study and at guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality of gathered data, and four further sections pertaining demographic and detention characteristics, self-reported health status and access to health services, lifestyles, with special focus on smoking habits and substance abuse, and participation in preventive, social, and rehabilitation programs. The section on demographic and detention characteristics focused on age, marital status, number of children, education attainment, employment status at prison entry, dealing with first incarceration, overall time spent in prison, stage of adjudication, and length of sentence. Self-reported health status and access to health care services were investigated using a set of 11 items appraising self-rated health and quality of life, change in self-reported health status following prison entry, frequency and reasons for accessing to health care services within prison, self-reported health problems at prison entry, self-reported current health problems, concerns about acquiring STDs, experiencing negative feelings, and suicide attempts both outside and inside prison. The response levels for items assessing perceived health and quality of life were arranged using "poor", "good", and "very good", change the perceived current health status compared with the status preceding prison entry was explored using a Likert-like scale with five-point response set ranging from "greatly worsened" to "greatly improved". Access to health care services were explored using a "yes" or "no" format, self-reported current symptoms or diseases and reasons for medical encounters were explored using a half-open item, while five-point ordered-category items ranging from "never" to "very often" were used to detail the frequency of arranging medical encounters with general practitioners and the frequency of experiencing negative feelings; concerns on acquiring STDs were evaluated using a discrete visual analog scale with responses ranging from 1 (perceived low risk) to 10 (perceived high risk). The lifestyle section comprised six items investigating smoking habits and substances addiction: smoking status ("never smoker", "former smoker", and "current smoker"), daily number of cigarettes smoked by current smokers; lifetime history of drugs use, both outside and inside prison, was appraised using items arranged on "yes" or "no" levels, whereas the type of substances was asked using half-open items. The section on preventive programs aimed to elicit prisoners participation to health promotion and rehabilitative programs provided in prison on tobacco smoking, alcohol abuse, STDs, and unhealthy nutrition habit was based on a set of items with "yes" or "no" response levels. Participation in social and rehabilitation programs was investigated by asking prisoners whether they had attended to vocational training programs ("yes" or "no"), and then offenders were asked to deem usefulness of such training programs in facilitating their reintegration into work and social life ("useful", "not useful", and "uncertain") and employment expectation once outside prison ("unemployed", "previous job", "new job", and "uncertain").

Questions on self-rated health and health modification during the period of incarceration were derived mainly from the SF-36 questionnaire, while questions on health service use and other items were drawn out from the literature. Items had been modified, if necessary, by taking into account feedback from the pretest.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee ("Mater Domini" Hospital of Catanzaro, Italy, study number 2005/47).

Statistical analysis

Two separate multiple stepwise logistic regression with backwards elimination were used to identify major independent predictors to the following primary outcomes of interest: self-rated health status (Model 1) and access to health services within prison (Model 2). For the purposes of analysis, the outcome variables originally consisting of three categories in the logistic analysis were collapsed into two levels. In Model 1, respondents were divided into those who rated as "poor" their health (recoded as 1) versus those who rated their health as "good/very good" (recoded as 0); in Model 2, respondents were divided into those who consulted "sometimes/often/very often" general practitioners (recoded as 1) versus those who consulted them "never/rarely" (recoded as 0). In all models, the independent variables included were the following: age (continuous, in years), marital status (unmarried/separated/divorced/widowed = 0, married = 1), education level (no formal education = 0, compulsory education or more = 1), employment status before entering prison (unemployed = 0, employed = 1), smoking habit (past/never smoker = 0, current smoker = 1), having ever used drugs (no = 0, yes = 1), first time incarceration (no = 0, yes = 1), time served in prison (continuous, in years), detention status (categorical, awaiting trial = 0, awaiting sentence = 1, serving sentence = 2), self-reported health problems at prison entry (no = 0, yes = 1), self-reported current health problems (no = 0, yes = 1), negative mood (never/rarely = 0, sometimes/often/very often = 1), and having ever attempted suicide in prison (no = 0, yes = 1). Before analyzing the data all cases for which there was at least one missing observation were discarded.

All tests for significance were two-sided and p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant and the significance level for removal variables from the models was set at p = 0.4. All analyses were conducted using the Stata software program, version 10.1 [19].

Results

Of the 908 eligible male prisoners, 650 agreed to participate in the study by returning the questionnaire for a response rate of 71.6%. Table 1 shows demographic, detection, and lifestyle characteristics of respondent prisoners. The mean age was 39.8 years, more than half were married, one-third had at least one dependent child at home, had not attained compulsory education, and were unemployed at the time of prison entry. Two-thirds were current smokers, one-third had used illicit drugs over the course of their life and 20% of them admitted to having used illicit drugs behind bars. Less than half had been incarcerated for the first time, about two-thirds were permanently condemned, the mean time spent in prison was 6.8 years, and the mean length of sentence was 10 years.

Self-reported health and quality of life

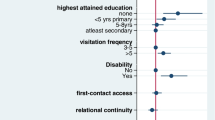

Table 2 shows the prisoners' perceived health status and quality of life. Overall, 31.6% and 43.5% of prisoners rated their health and perceived quality of life "poor". Compared to the time of prison entry, 60% reported that their health had worsened or greatly worsened and 35.1% were "extremely" concerned about their health. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that older prisoners (OR = 1.06; 95% CI = 1.03-1.08), those with lower education level (OR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.33-0.88), those experiencing negative feelings more frequently (OR = 4.13; 95% CI = 2.45-6.95), who attempted suicide within prison (OR = 2.48; 95% CI = 1.31-4.69), and who reported health problems on prison entry (OR = 2.54; 95% CI = 1.58-4.08) were significantly more likely to perceive a worse health status (Model 1 in Table 3).

Self-reported health problems and access to health services within prison

Table 4 lists prisoners' self-reported current symptoms or diseases and reasons for arranging medical encounter. The rate of prisoners self-reporting health problems increased during the incarceration growing from 30% on prison entry to 82% at the time of questionnaire delivery. The top six health problems are dental health problems, arthritis or joint pain, eye problems, gastrointestinal diseases, emotional problems, and high blood pressure. Suicide was more frequently attempted within (13.6%) than outside the prison (7.9%). Furthermore, prisoners were afraid of possible STDs since over 60% of them rated a score ranging from 7 to 10. Prisoners consulted general practitioners about 6 times in the last year of incarceration while hospital admission was necessary for 11.4%. Consultations with general practitioners were significantly more frequent for older prisoners (OR = 1.02; 95% CI = 1.01-1.05), for those serving a sentence (OR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.11-3.30), for those experiencing negative feelings more frequently (OR = 2.00; 95% CI = 1.31-3.05), and for those reporting health problems on prison entry (OR = 3.81; 95% CI = 2.32-6.25) (Model 2 in Table 3).

Participation to health promotion and social rehabilitative programs

Educational and health promotion programs, oriented towards the adoption of healthy behaviors in relation to alcohol consumption, STDs, smoking, and eating habits, are regularly provided within the prison healthcare system. Although all prisoners are invited to participate in these programs, only 9% were involved in programs smoking cessation/prevention, 8.9% in responsible alcohol consumption, 5.6% for prevention of STDs, and 6% to modify unhealthy eating habits. Moreover, almost half have participated in vocational training programs and 85% of them deemed such training "useful" but only 11.4% believed that it would allow them to find a new job after prison release.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge the present study is the first attempt to assess prisoners' self-reported health status in Italy. The results confirm previous studies that prisoners have a poor self-reported health status, high morbidity rate, and a frequent access to prison health services. It should be noted that we did not test the prison effect in determining the health status, the quality of life, and the access to health services, because we did not expect that structural and organizational differences between the selected prisons can play a role on these outcomes of interest. This is also supported by the results of a previous study conducted by some of us in the same four prisons with no significant differences among centers with regard the oral health status [20].

About 32% of prisoners rated their health as "poor", despite an average age of 40 years. In a study conducted on the Italian males general population, 1.9% of those aged 35-44 and 6.7% of all age groups rated their health as "poor" or "fair" and this percentage rises to 9.7% in Calabria. Moreover, the characteristics of the sample who perceived the worst health status were similar to those of the general population and it has been observed more frequently among those with a lower educational level and older [21]. These data clearly suggest that perceived health status is worse in the most disadvantaged subgroups. These findings are consistent with those reported in Australia where 28% of male prisoners rated their health as either "poor" or "fair" compared with 15% in the community [2]. Another study in the same area found that the perceived health was deemed as "poor" or "fair" by 24% and 30% of aboriginal and non-aboriginal male prisoners, respectively [22]. In the United States, half of newly admitted prisoners rated their health as "good", "fair", or "poor" [9], whereas in another study none of male prisoners rated their health as "poor", 20% as "fair", and 53% as "good" [23]. As expected, our findings that older age is a predictor of self-reported poor health is in accordance with other studies [16, 23, 24]. The finding that young prisoners are prone to evaluate their health more positively than those older is confirmed by Butler et al, who reported that 91% of offenders aged 15-24 in Australia evaluated their health as "excellent", "very good", or "good" [25]. Moreover, psychological conditions are also associated with perceived poor health and these factors are well documented risk factors for both poor health status and incarceration.

The prison system must be considered as a filter that selects and concentrates subjects with certain characteristics and trying to establish a relationship of causality about the effect of incarceration on health of prisoners may be misleading and controlling for confounders is very difficult. Other factors might simultaneously affect both incarceration and health and bias the apparent effect of incarceration. Instead, prison system should be regarded as an ally of public health, as an opportunity for providing treatment and education to individuals at risk and underserved. But prison can have long-term effects on prisoners' health. Schnittker et al [26] suggest that incarceration may have a negative effect on prisoners' health, in particular after release, since in custody they are unable to develop normal credentials and the distance and the time spent in prison negatively affect social integration, especially with their own family.

Self-reported health problems and access to health services

A high prevalence of prisoners' self-reported diseases (82%), whereas lower values have been reported in the general population (13.1%) and in Calabria (15.7%) [21]. The top rated current health issue was dental health problems. This result is supported by the findings of a study, conducted by some of us, with only 2% of examined prisoners having no history of caries [20]. The authors also suggested the need for programs to improve oral health. Improving oral health can improve overall health [27]. Moreover, as expected considering the characteristics and the risk factors of the population surveyed, emotional and gastrointestinal problems were most frequently reported and this is consistent with previous results [2, 9, 16, 28].

Among all demographic characteristics, only age was significantly associated with self-reported use of health services with older prisoners that were more likely to access to these services within prison. Not surprisingly, and according with previous studies, no effect has been found regarding other demographic characteristics [2, 23, 29, 30]. It has been observed that prisoners seek care when ill and they use health services in prison 3 to 4 times more frequently than the general population and this use is linked to the high morbidity rate on entry, but this is not sufficient to explain the difference in health services utilization [31, 32]. This inconsistency is particularly evident in our context in which both prisoners and general population have universal health care access. The high rate of health services use may also be explained by the fact that the therapy with methadone and buprenorphine is given for free to all prisoners with history of substance use as an effective treatment for opiate dependence and, hopefully, to reduce drug-related diseases and recidivism for prisoners.

Participation in health promotion programs was very low and this may reflect the lack of adequate programs offered to prisoners for the correction of unhealthy lifestyles. Newly admitted prisoners are advised by physician during examination, and effective prevention programmes are needed for people passing through the correctional system in Italy.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations in this study. There is the possibility of a selection bias since almost 30% of prisoners did not participate and the mean age of the sample was slightly higher than that of the population of prisoners in the selected prisons, but this should not pose a threat to the generalizability to the overall prisoner population, since the group most prevalent in Italian prisons was between 30 and 39 years [33]. Moreover, caution is required in making cross-country comparisons of perceived health status, mainly because items assessing self-reported health status and quality of life were arranged on different level of responses. However, we believe that our results reflects the actual estimate of self-reported health. In fact, there are many alternative questionnaires assessing people's health and quality of life, each of them using different wording and different set of responses but the answers to the various self-reported health items are highly correlated [14]. Finally, misclassification may have been introduced by the use of self-reported history of health problems.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that prisoners have a poor health status because of specific problems and care needs. However, prison health services are almost equivalent to those provided in the community since physicians act as general practitioners and most health problems are adequately addressed. But, the prison system appears to be a "bad" ally of public health considering that it seldom provides programs aimed at health promotion or facilitating social reintegration. Our findings give a cue for the provision of programs aimed at correcting risk behaviour and preventing the long-term effects of incarceration on prisoners' health.

References

Galea S, Vlahov D: Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002, 117: S135-S45.

Butler T, Kariminia A, Levy M, Murphy M: The self-reported health status of prisoners in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004, 28: 344-50. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2004.tb00442.x.

Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA: Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008, 59: 170-7. 10.1176/appi.ps.59.2.170.

Macalino GE, Dhawan D, Rich JD: A missed opportunity: hepatitis C screening of prisoners. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95: 1739-40. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056291.

Aerts A, Hauer B, Wanlin M, Veen J: Tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in European prisons. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006, 10: 1215-23.

Thomas JC, Levandowski BA, Isler MR, Torrone E, Wilson G: Incarceration and sexually transmitted infections: a neighborhood perspective. J Urban Health. 2008, 85: 90-9. 10.1007/s11524-007-9231-1.

Gupta S, Altice FL: Hepatitis B virus infection in US correctional facilities: a review of diagnosis, management, and public health implications. J Urban Health. 2009, 86: 263-79. 10.1007/s11524-008-9338-z.

Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU: The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009, 99: 666-72. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279.

Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW: Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health. 2000, 90: 1939-41. 10.2105/AJPH.90.12.1939.

Pratt D, Piper M, Appleby L, Webb R, Shaw J: Suicide in recently released prisoners: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2006, 368: 119-23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69002-8.

Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD: Release from prison - A high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 157-65. 10.1056/NEJMsa064115.

Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA: All-cause and cause-specific mortality among men released from state prison, 1980-2005. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 2278-84. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121855.

Anasseril ED: Care of the mentally ill in prisons: challenges and solutions. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007, 35: 406-10.

Fayers PM, Sprangers MA: Understanding self-rated health. Lancet. 2002, 359: 187-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07466-4.

DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P: Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 267-75. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x.

Fazel S, Hope T, O'Donnell I, Piper M, Jacoby R: Health of elderly male prisoners: worse than the general population, worse than younger prisoners. Age Ageing. 2001, 30: 403-7. 10.1093/ageing/30.5.403.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, ISTAT 2006. Annuario statistico italiano 2006. Accessed on April 20, 2011, [http://www.istat.it/dati/catalogo/asi2006]

Rea LM, Parker RA: Designing & conducting survey research: a comprehensive guide. 2005, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Imprint, 30-2. Third

Stata Corporation: Stata Reference Manual Release 10: 2007, College Station, TX, USA

Nobile CGA, Fortunato L, Pavia M, Angelillo IF: Oral health status of male prisoners in Italy. Int Dent J. 2007, 57: 27-35.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, ISTAT: 2007. Condizioni di salute, fattori di rischio e ricorso ai servizi sanitari. Accessed on February 10, 2010, [http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_609_allegato.pdf]

Kariminia A, Butler T, Levy M: Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal health differentials in Australian prisoners. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007, 31: 366-71. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00089.x.

Lindquist CH, Lindquist CA: Health behind bars: utilization and evaluation of medical care among jail inmate. J Community Health. 1999, 24: 285-303. 10.1023/A:1018794305843.

Colsher PL, Wallace RB, Loeffelholz PL, Sales M: Health status of older male prisoners: a comprehensive survey. Am J Public Health. 1992, 82: 881-4. 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.881.

Butler T, Belcher JM, Champion U, Kenny D, Allerton M, Fasher M: The physical health status of young Australian offenders. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008, 32: 73-80. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00169.x.

Schnittker J, John A: Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007, 48: 115-30. 10.1177/002214650704800202.

Treadwell HM, Formicola AJ: Improving the oral health of prisoners to improve overall health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95: 1677-8. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.073924.

Kariminia A, Law MG, Butler TG, Levy MH, Corben SP, Kaldor JM, Grant L: Suicide risk among recently released prisoners in New South Wales, Australia. MJA. 2007, 187: 387-90.

Alexopoulos EC, Geitona M: Self-rated health: inequalities and potential determinants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009, 6: 2456-69. 10.3390/ijerph6092456.

Leukefeld CG, Staton M, Hiller ML, Logan TK, Warner B, Shaw K, Purvis RT: A descriptive profile of health problems, health services utilization, and HIV serostatus among incarcerated male drug abusers. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002, 29: 167-75. 10.1007/BF02287703.

Marshall T, Simpson S, Stevens A: Use of health services by prison inmates: comparisons with the community. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001, 55: 364-5. 10.1136/jech.55.5.364.

Feron JM, Paulus D, Tonglet R, Lorant V, Pestiaux D: Substantial use of primary health care by prisoners: epidemiological description and possible explanations. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59: 651-5. 10.1136/jech.2004.022269.

Ministero della Giustizia: Detenuti per classi di età. Anni 2005-2010. Accessed on April 26, 2011, [http://www.giustizia.it/giustizia/it/mg_1_14_1.wp?facetNode_1=1_5_2&previsiousPage=mg_1_14&contentId=SST613888]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/529/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the Prison Regional Authority for allowing us to carry out this study. Also we would like to extend our sincere thanks to the Directors and the Staff of the penal institutions for their great support and to all prisoners for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CGAN participated in the design of the study, data collection, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the data. DF participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation of the data, and wrote the article. GN participated in the design of the study and data collection. CP participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. IFA, the principal investigator, designed the study, was responsible for the data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of the data, and wrote the article. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nobile, C.G., Flotta, D., Nicotera, G. et al. Self-reported health status and access to health services in a sample of prisoners in Italy. BMC Public Health 11, 529 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-529

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-529