Abstract

Background

In the past years, cumulative evidence has convincingly demonstrated that the work environment is a critical determinant of workers' mental health. Nevertheless, much less attention has been dedicated towards understanding the pathways through which other pivotal life environments might also concomitantly intervene, along with the work environment, to bring about mental health outcomes in the workforce. The aim of this study consisted in conducting a systematic review examining the relative contribution of non-work determinants to the prediction of workers' mental health in order to bridge that gap in knowledge.

Methods

We searched electronic databases and bibliographies up to 2008 for observational longitudinal studies jointly investigating work and non-work determinants of workers' mental health. A narrative synthesis (MOOSE) was performed to synthesize data and provide an assessment of study conceptual and methodological quality.

Results

Thirteen studies were selected for evaluation. Seven of these were of relatively high methodological quality. Assessment of study conceptual quality yielded modest analytical breadth and depth in the ways studies conceptualized the non-work domain as defined by family, network and community/society-level indicators. We found evidence of moderate strength supporting a causal association between social support from the networks and workers' mental health, but insufficient evidence of specific indicator involvement for other analytical levels considered (i.e., family, community/society).

Conclusions

Largely underinvestigated, non-work determinants are important to the prediction of workers' mental health. More longitudinal studies concomitantly investigating work and non-work determinants of workers' mental health are warranted to better inform healthy workplace research, intervention, and policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For the past three decades, epidemiological research, influenced predominantly by the Demand-Control-Support[1] and Effort-Reward Imbalance[2] models, has highlighted the connection between key features of the psychosocial work environment (e.g., decision latitude, psychological demands, social support, rewards) and the deterioration of workers' mental health. This substantial body of work has recently been the focus of several systematic reviews of work-specific determinants[3–5] and leveraged interventions[6–10]. Interestingly, the literature has devoted much less attention to understanding the pathways through which other pivotal life environments might also concomitantly intervene, along with the work environment, to bring about improved mental health outcomes in the working population[11–13]. The current study seeks to bridge this gap by systematically reviewing the relative contribution of non-work determinants to workers' mental health[14].

The non-work domain: Conceptual and analytical considerations

The construct "non-work domain" has taken on multiple meanings in the literature on workers' mental health, ranging from chronic stressors and life events[15] to the inclusion of health-related lifestyles and symptoms[16]. Such broad conceptual heterogeneity in the non-work domain construct represents a significant limitation for advancing research on workers' mental health since the specific contribution of non-work determinants remains diffuse and unclear.

In the interest of conceptual clarity, we have borrowed from past work on social structures, agency and workers' mental health to delineate specific constitutive attributes of the non-work domain [12, 13]. In line with the sociological theory of agency-structure [17, 18], we view macro- (e.g., society), meso- (e.g., workplace, networks) and microsocial structures of the daily life (e.g., family) as many life environments in which workers routinely find themselves.

Following from this, workers' mental health can be conceptualized as resulting from the cumulative opportunity structures and constraints embedded in these life environments to which workers are exposed [12, 13, 19]. Consequently, workers' mental health becomes not only rooted in the work environment, but also in other pivotal life environments such as the family, networks, community, and, more broadly, the society to which workers belong. These other life environments constitute what we define here as the non-work domain. The attributes of the non-work domain are thus of inherently social nature, and should analytically be distinguished from any specific attributes pertaining to the workers as individual agents encompassing notably "reflectiveness, rationality, creativity, demography, affect, the body, biology, representations, perceptions, motivations, habits, and attitudes" [12].

This systemic approach of the non-work domain is congruent with integrative work on social integration [20] and on psychosocial risk factors of home and community settings [21]. Accordingly, the non-work domain can be posited to shape workers' mental health through causally and dynamically intertwined mechanisms at three levels of analysis: 1) the macrosocial level of community or society (e.g., culture, socioeconomic factors); 2) the mesosocial level of networks (e.g., social network structures, characteristics of network ties); and 3) the microsocial level of the family unit (e.g., marital and parental relationships).

Furthermore, in line with recent studies on the material and psychosocial pathways of health[22, 23], we have posited that each non-work analytical level and its constitutive mechanisms are distinctly linked to workers' mental health outcomes through objective and subjective measures of non-work determinants.

Based on the propositions mentioned above that define the non-work domain construct, this systematic review aims to answer the following research question: What is the nature of the causal association between non-work determinants and workers' mental health, once the concomitant contribution of work determinants is accounted for?

Methods

Definition and inclusion parameters

This systematic review examined the concomitant causal association between work and non-work determinants of workers' mental health. The definition of mental health put forth encompassed three widely investigated outcomes: psychological distress, depression, and burnout. Work exposure referred to the psychosocial work environment described by the Demand-Control-Support model[1], the Effort-Reward model[2], and any related concepts (e.g., organizational justice), as well as objective features of the work contract (e.g., working hours). Drawing from our framework, we defined non-work exposure from the levels of analysis (e.g., family, networks, community, society) that describe the non-work domain[12, 20].

Eligibility criteria for selecting the studies that best captured the nature of the explanatory dynamics investigated focused on observational longitudinal studies of working-age adults. In order to minimize bias, the study design specified the following inclusion parameters. Firstly, we opted for community-based as opposed to clinical-based sampling of workers to ensure that selected workers were not followed for other concurrent medical conditions implicating potential reverse causation effects of mental health on workers' assessment of their work and non-work exposures[24]. Secondly, a sample size of at least 200 workers was chosen in order to make reasonable statistical power assumptions about the investigated work and non-work exposures. With a conservative variable-to-cases ratio of 1:10 [25], we estimated that comprehensive studies based on extensive work exposure (e.g., indicators from the Job-Demand-Control and Effort-Reward Imbalance models), non-work exposure (i.e., family, network and community/society-level indicators) and adjustment strategies (e.g., lifestyles, sociodemographic profile, chronic health conditions) would be optimally targeted by our research question. Thirdly, a minimum observation period of at least 12 months in order for work exposure to have a stable effect on mental health was also observed in conformity with similar research efforts[5]. Fourthly, a multivariate evaluation of work and non-work exposures with reports of their respective effect sizes was required. Measurements for mental health also needed to be based on multidimensional, psychometrically sound instruments; therefore, we considered both continuous and binary statistical treatments of mental health outcomes[26, 27]. Lastly, this review focused on empirical research published in English and French (grey literature excluded).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was designed to assessed the non-work domain in the literature [28]. Multiple databases were queried from the start date through July 26, 2008: Cinhal (Ovid), Psycinfo (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Medline (Ovid), EBM (all databases, Ovid), Sociological Abstracts (ISI Web), the Social Sciences Citation Index (ISI Web), and the Arts and Human Citation Index (ISI Web). We elaborated an electronic search strategy that included indexed and free terms in keeping with similar research on outcomes[5, 7] and work-exposure definitions[3, 5], although we deduced non-work exposure from our framework (see Additional file 1). We also conducted a confirmatory search strategy based on an inductive screening of bibliographies from potentially eligible studies, relevant reviews[3–5, 24], and an electronic search of Medline (OVID) from 2005 to 2008 that omitted the non-work exposure filters introduced in the original search strategy.

Data extraction and management

We applied a two-stage selection process to data extraction. In the first stage, we examined titles and abstracts to ascertain potential study eligibility. One researcher conducted the first-stage iteration, which a second researcher then corroborated using a random subsample (N = 240, kappa = 0.89). One researcher conducted the second data-extraction stage, which focused on full-text, potentially eligible studies. Disagreements throughout both the extraction and appraisal phases were resolved by discussion with a third researcher. We used Nvivo 2.0 and SPSS 15.0 to manage data from the extraction phase[29, 30].

Critical appraisal and synthesis of the evidence

As anticipated, the heterogeneity in the conceptualization and operationalization of the non-work domain precluded meta-analysis of the data. We therefore opted for a narrative synthesis based on a critical appraisal that included both conceptual and methodological considerations (see Additional file 2). The conceptual component of the critical appraisal examined the level of comprehensiveness associated with the conceptualization and operationalization of the non-work domain and comprised two components.

Analytical breadth corresponded to the number of analytical levels (e.g., family, networks, community, society) considered by the included studies. For clarification purposes, we attributed analytical levels as follows: 1) the family modality referred specifically to workers' partner, children, and parents; 2) the network modality referred to relatives, friends, and generic references to social relationships (e.g., "people"); and 3) the community/society modality referred to community or societal features (e.g., occupational status based on national classification systems). Scores were derived additively if more than one analytical level was present for a given study, higher scores indicating greater analytical breadth. Illustratively, joint inclusion of family and community levels in single or multiple indicators would earn two stars out of a possibility of three stars.

Analytical depth measured the extent to which, for a given analytical level, multiple indicators of the non-work domain were included within studies. We distinguished among low (1 indicator), moderate (2 or more indicators), and high (2 or more indicators of a single construct with both objective and subjective assessments) levels of analytical depth. Objective indicators comprised social position markers (e.g., marital status) or cumulative exposure to non-work factors (e.g., life events)[31], whereas subjective indicators comprised workers' appraisals of the level of stressfulness experienced relative to non-work factors.

Once we had mapped conceptual comprehensiveness, we measured methodological quality using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS)[32, 33], a validated 9-item questionnaire that evaluates design robustness based on cohort selection, adjustments for confounding factors, and ascertainment of exposures or outcomes. We adopted a descriptive approach to characterize the strength of the evidence, using a multiple-criteria triangulation[34]. Three criteria were examined: 1) adequacy of methodological quality (relatively high methodological quality set at NOS score > mean NOS score); 2) consistency of findings (at least 75% of the studies reporting a significant finding at p < 0.05 in the anticipated direction for exposure-outcome association); and 3) strength of causal association (strong magnitude set at OR≥2.0 or ≤0.75). We considered strength of evidence "strong" if all three criteria were cumulatively satisfied (i.e., at least 75% of relatively high-quality studies reporting results of strong magnitude), "moderate" if consistent results were obtained from high-quality studies only or a mixture of high- and low-quality studies in the anticipated direction for exposure-outcome association independently from the strength of association, and "insufficient" if consistency could not be reached or was based on low-quality studies only (see Additional file 3 for further details on the decision process followed). In determining the strength of evidence, we duplicated observations at each analytical level considered for such cases where analytical levels could not specifically be untangled from indicator measurement.

Because all studies provided direct evidence or references with sufficient information for valid evaluations to be made, it was not necessary to contact any study authors for clarification. In order to minimize potential conflation bias in the results, studies from a single cohort sharing partial data overlap were examined separately provided that they cumulatively present: a) different endpoints; and b) a combination of substantively different work and non-work exposures, and mental health outcomes. In the presence of multiple non-independent studies and studies relying on multiple analytical strategies, we selected the study yielding the highest NOS score. Two reviewers independently performed iterations in the critical appraisal phase, with interrater agreement levels for methodological and conceptual components estimated at kappa = 0.79 and kappa = 0.76 respectively. This systematic review follows the recommendations of the MOOSE guidelines (see Additional file 4) [14].

Results

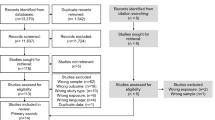

We retrieved a total of 4,032 studies from the original literature search. Of the 96 studies identified as potentially eligible, we selected 7 for review[12, 35–40]. Reasons for exclusions were: cross-sectional design[41, 42], sample size[43–48], observation period[49–56], lack of conformity with outcome[57–59], or work exposure definition[60–76]. From those studies meeting the preceding criteria, we excluded additional studies based on the absence of non-work exposure[77–103], failure to report size effects for non-work exposure[104–126], univariate examination of work and non-work factors[127], and non-independent samples[13, 46, 128]. We retrieved six additional studies from the confirmatory search (full details available from authors)[129–134]. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process followed to determine eligibility. Included studies comprised 12 prospective cohort studies[12, 36–40, 129–134] and 1 retrospective case-control study[35].

Table 1 summarized the characteristics of the included studies. All studies were conducted in Europe or North America. Among the 13 studies reviewed, 6 were derived from independently designed longitudinal cohorts [35, 36, 38–40, 129], while the 7 remaining studies involved two independently designed longitudinal cohorts, namely the National Population Health Survey [12, 130, 132, 133], and the Whitehall study [37, 131, 134]. A wide range of outcome measurement was used for psychological distress or depression, burnout was not investigated by any studies. The follow-up period varied from 1 to 10 years. All studies controlled for sociodemographic profile (e.g., age, gender), with fewer reports of adjustments for past mental health history, personality traits and lifestyles.

Nature and strength of the evidence linking non-work factors to mental health

As shown in Table 2 adequate methodological (M = 5.5, SD = 1.2) and conceptual (M = 4.3, SD = 1.4) quality described the analytical sample. The studies with the highest methodological quality scores [12, 39, 132] did not get the maximum score of 9 on the NOS scale due to non-representative samples of the general workforce[39, 132], inclusion of workers with mental health problems at baseline[12, 39], and ascertainment of mental health outcomes by a non-medical expert[12, 132]. Overall, seven of the included studies were of relatively high methodological quality[12, 35, 39, 40, 130, 132, 133]. An examination of the analytical breadth of the selected studies revealed that all studies considered the family level of analysis, while a majority of them also extended their analyses to the networks [12, 36–39, 131, 133, 134] and/or the community or society (as per Table 1)[12, 40, 130–134]. The rest of this section discusses the strength of evidence for each analytical level of social organization and its indicators as reported in Table 3.

Family

Partner relationships were systematically included in all studies. Consistent, non-significant evidence that marital status‚ as an objective indicator‚ affected mental health outcomes was reported by 4 high-[12, 35, 130, 132] and 3 low-quality studies[37, 129, 131]. The one low-quality study that succeeded in modeling a significant, negative relationship between marital status and depressive symptoms in the GAZEL cohort investigated the effect of multiple modalities of relationships rather than the conventional dichotomy "alone/in relationship"[38]. Non-significant effects of subjectively measured maritally strained relationships were reported by 3 high-quality studies[12, 39, 130]. Comparatively two low-quality studies[131, 134] from the Whitehall cohort found associations of modest magnitude for the subjective indicator of "partner's support". Of note, "partner's support" assessed perceived positive and negative aspects of social support from others whom respondents designated as "closest" to them, a designation that predominantly, though not universally, referred to partners. One high-quality study alternatively demonstrated a significant negative relationship between the objective indicator "years together" and the subjective indicator "marital-role quality" in relation with psychological distress in a sample of dual-earner couples[40]. The objective indicator for parental status yielded consistent, non-significant results (4 high-[12, 40, 130, 132] and 1 low-quality studies[37]). One high-quality study based on the NPHS cohort found significant yet weak associations between child-related strains and psychological distress[12].

Other family-related indicators pertained to structural characteristics of the family and chronic or severe family-related stressors. Three high-quality studies[12, 40, 133] failed to reproduce a significant association between the objective indicator for household socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes, whereas one high-quality study[133] confirmed the absence of a similar effect for chronic financial stress. Two high-quality studies from the NPHS cohort reported a significant yet inverted effect of household income on major depressive disorders and psychological distress among men[130, 132]. Two low-quality studies[36, 38] found supportive evidence of an effect of life events, of which one from the GAZEL cohort reported results of modest magnitude for men and of high magnitude for women. In both studies, measurement of life events included items related to family members (e.g., partner, child, parent) and to the extended network (e.g., relatives, friends). By contrast, one high-quality study[133] did not find any association for family-specific life events (e.g., partner, child, parent) alone. Finally, one low-quality study showed modest to strong effects for the family stressor "home control" in the Whitehall cohort[37].

In summary, the evidence supporting an effect for family-level factors on workers' mental health appears to be insufficient. This conclusion holds regardless of the integration of indicators measuring the combined influence of family- and network-level into the analysis.

Networks

Eight studies examined the relationship between network features and workers' mental health. Of these, one low-quality study from the Whitehall cohort showed an association of modest magnitude between the objective indicator of providing care for an elderly or disabled relative and mental health outcomes among men[37]. From the same cohort, two low-quality studies [131, 134] reported mixed evidence for network structural features (e.g., number of people in the network, frequency of contacts). As for network stressors, the conclusive results obtained by combining objectively measured network- and family-level life events, discussed above[36, 38], were not reproduced when one high-quality study[133] jointly considered community-level events with network-level events. As for subjective measures, one high-quality study from the NPHS cohort reported strong protective effects for non-work social support[12], whereas two low-quality studies from the Whitehall cohort[131, 134] noted modest to strong effects. These latter studies used broad expressions to describe network relationships (e.g., "nearest confidant", "someone" and "closest nominated persons"), whereas the only non-conclusive study used a group-specific indicator of social support ("friends")[39]. The evidence for effects on workers' mental health from network-level factors is therefore of moderate strength according to our scoring system but only for subjective indicators associated to social support.

Community/Society

In all, seven studies investigated the community/society analytical level. In terms of community/society structural characteristics, out of the four studies relying on national occupational classification systems to describe occupational status, prestige and average income[12, 40, 130, 132], only one found an inverted protective association for lower socioeconomic occupational groups on psychological distress in the NPHS cohort[130]. Similarly, one high-quality study based on a multilevel analysis of the NPHS cohort showed a marginal but significant association between societal occupational structure and psychological distress after adjustment for individual-level factors[12]. Alternatively, two low-quality studies [131, 134] reported inconsistent evidence of an association between a social network index based on network (e.g., relatives, friends) and community-member exchanges (e.g., visits to social clubs, church). One high-quality study[133] reported non-significant effects on psychological distress for joint network- and community-level life stressful events. No study assessed the relationship between community/society-level subjective indicators and workers' mental health. Support for an effect for community/society-level factors on workers' mental health has proven insufficient.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to provide robust conceptual and methodological guidelines for assessing the relative contribution of non-work determinants to workers' mental health above and beyond that of work determinants. In all, 13 longitudinal were evaluated for this review, among which 7 of these studies were of high methodological quality.

This review makes a salient contribution to the occupational stress literature by pointing out the lack of comprehensive and cumulative knowledge about the concomitant relationships between work and non-work domains in the explanation of workers' mental health. Indeed, among all potentially eligible longitudinal studies that met our selection criteria in terms of publication type, population, design, outcome and work exposure, the majority (N = 40/79; 50.6%) did not consider non-work factors, and nearly one third (N = 26/79; 32.9%) included non-work factors with no reports of their specific effect sizes. Moreover, when we examined the analytical breadth of the three levels of social organization considered (i.e., family, networks, community/society), we saw that the current state of knowledge about such concomitant relationships was essentially located at the family and network level. As far as analytical depth was concerned, although studies used multiple indicators of the non-work domain normatively, for a given non-work factor only a minority of studies sought to assess the joint contribution of objective and subjective measurement. Overall, we found insufficient evidence for any effects on workers' mental health of family-or community/society-level factors, although we did find evidence of moderate strength for social support at the network level.

These findings highlight important gaps in research on workers' mental health. Currently, mounting evidence shows that social features from every life environments are linked to mental health outcomes in the general population[135, 136]. The nature of the pathways through which these life environments dynamically intersect with what goes on in the work environment raises critical issues with regard to the relational, spatial and temporal dynamics of workers' mental health. Unraveling such dynamics throughout the trajectory of workers' active life is also of significant interest for a wide range of public health-related issues such as work-life balance and civic participation[137, 138]. This however can only be adequately addressed with the recognition that a greater attention ought to be paid to non-work determinants in the design of high quality longitudinal studies in the short term.

While highly informative, certain methodological limitations apply to this review. Firstly, we limited study eligibility to English- and French-language publications that did not refer to the grey literature. The strength of the confirmatory search strategy we developed‚ however‚ appeared exhaustive and comprehensive enough to eliminate significant omissions. The population we chose for analysis excluded studies based on clinical subjects due to potentially accrued individual vulnerability to stress. Further research is needed to thoroughly clarify this premise. Secondly, the heterogeneity of study design posed challenges for comparability. We partially addressed this limitation in our appraisal with the NOS instrument[139]. Hence, although the treatment of confounders was uneven, studies that minimally controlled for age and gender, which are considered primary determinants of mental health, received higher scores. Thirdly, we made full-workforce representativeness a reference criterion so that the dynamics we were investigating would remain generalizable. This threshold may appear high, but in our opinion it led to sounder conclusions concerning gender, age, and socioeconomic variations in the distribution of work, non-work factors, and mental health outcomes, which sampling strategies excluding any of these determinants might not have detected[35, 39]. Fourthly, ascertaining outcomes using the NOS instrument was likely more consistent with epidemiological approaches to mental health outcomes. Alternative scoring for operationalizations based on a continuum however yielded the same results.

Lastly, the methodological decision to integrate studies with partial data overlap from a single cohort into our narrative synthesis merits additional consideration. This decision was initially informed by the need to translate a balance between the level of comprehensiveness necessitated to allow for such an exploratory synthesis to be conducted, and the level of restrictiveness in studies inclusion criteria necessitated to rigorously contain a conflation bias in the results. This was best achieved in our view by allowing multiple studies from a single cohort to be considered for evaluation following stringent criteria at different stages of our methodology (i.e., cumulative criteria for studies inclusion, high threshold for consistency in findings from the critical appraisal). As illustrated in Table 1, marginal overlaps in endpoints, work and non-work exposures and mental health outcomes were documented from the NPHS and the Whitehall studies. Again, we can tentatively hypothesize that distinctive causal dynamics potentially associated with design variations accounted for the substantive differences observed in results for comparable indicators between studies from a single cohort. A critical reflection as to the extent to which overlap in causal dynamics in studies from single cohorts should be validly considered in future systematic reviews is warranted.

Research implications

This systematic review identified two key recommendations that should be of immediate interests for research on workers' mental health.

Recommendation 1

We recommend that future longitudinal research systematically consider both work and non-work determinants of workers' mental health. In this review, 9 out of 13 studies were successful in detecting significant and independent effects over time on outcomes for non-work factors after controlling for work factors and other individual-level characteristics such as age, gender, lifestyles and past mental health history. Yet, lack of cumulative knowledge rather than inconsistency in results emerged as the primary reason that the evidence for effects of the non-work factors on workers' mental health was only modest. All analytical levels (i.e., family, networks, community/society) and their respective indicators (i.e., subjective, objective) should be prioritized.

Recommendation 2

We further recommend that robust methodological and conceptual parameters be explicitly stated and applied. Careful considerations about the conceptualization and operationalization of the non-work domain are warranted given that its construct definition captures distinct levels of social organization. The opportunity to analytically and empirically untangle in a straightforward way the specific effects of work and non-work indicators is paramount should evidence-based interventions and policy be efficiently informed by longitudinal studies targeting workers' mental health.

Conclusion

By combining insights of several disciplines such as epidemiology and sociology, this systematic review has outlined that the non-work domain is a largely underinvestigated area of research pertaining to the study of workers' mental health. In the future, it is only by rigorously addressing the quality of the state of the knowledge both from a conceptual and methodological standpoint that healthy workplace policy, intervention and research can comprehensively balance the ways in which work and non-work domains jointly contribute to the explanation of workers' mental health.

References

Karasek R, Theorell T: Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. 1990, New York, NY: Basic Books

Siegrist J: Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996, 1 (1): 27-41.

Bonde JP: Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup Environ Med. 2008, 65 (7): 438-445. 10.1136/oem.2007.038430.

de Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MA, Houtman IL, Bongers PM, de Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM: "The very best of the millennium": longitudinal research and the demand-control-(support) model. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003, 8 (4): 282-305.

Stansfeld S, Candy B, Stansfeld S, Candy B: Psychosocial work environment and mental health-a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006, 32 (6): 443-462.

Bambra C, Egan M, Thomas S, Petticrew M, Whitehead M: The psychosocial and health effects of workplace reorganisation. 2. A systematic review of task restructuring interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007, 61 (12): 1028-1037. 10.1136/jech.2006.054999.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bültmann U, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Verhoeven AC, Verbeek JH, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Verbeek JHAM: Interventions to improve occupational health in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, CD006237-2

Egan M, Bambra C, Thomas S, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Thomson H: The psychosocial and health effects of workplace reorganisation. 1. A systematic review of organisational-level interventions that aim to increase employee control. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007, 61 (11): 945-954. 10.1136/jech.2006.054965.

Lamontagne AD, Keegel T, Louie AM, Ostry A, Landsbergis PA: A systematic review of the job-stress intervention evaluation literature, 1990-2005. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2007, 13 (3): 268-280.

Ruotsalainen J, Serra C, Marine A, Verbeek J: Systematic review of interventions for reducing occupational stress in health care workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008, 34 (3): 169-178.

Stokols D, Pelletier KR, Fielding JE: The ecology of work and health: research and policy directions for the promotion of employee health. Health Educ Q. 1996, 23 (2): 137-158.

Marchand A, Demers A, Durand P: Do occupation and work conditions really matter? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress experiences among Canadian workers. Sociol Health Illn. 2005, 27 (5): 602-627. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00458.x.

Marchand A, Demers A, Durand P: Social structures, agent personality and workers' mental health: a longitudinal analysis of the specific role of occupation and of workplace constraints-resources on psychological distress in the Canadian workforce. Human Relations. 2006, 59 (7): 875-901. 10.1177/0018726706067595.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology - a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000, 283 (15): 2008-2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

Klitzman S, House JS, Israel BA, Mero RP: Work stress, nonwork stress, and health. J Behav Med. 1990, 13 (3): 221-243. 10.1007/BF00846832.

Virtanen M, Koskinen S, Kivimäki M, Honkonen T, Vahtera J, Ahola K, Lonnqvist J: Contribution of non-work and work-related risk factors to the association between income and mental disorders in a working population: the Health 2000 Study. Occup Environ Med. 2008, 65 (3): 171-178. 10.1136/oem.2007.033159.

Giddens A: La constitution de la société. 1984, Paris: Presses universitaires de France

Archer MS: Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. 1995, New York: Cambridge University Press

Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR: Why are some people healthy and others not? The determinants of health of populations. 1994, New York, NY: Aldine Transaction

Berkman LF, Glass T: Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social epidemiology. Edited by: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. 2000, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 137-173.

Egan M, Tannahill C, Petticrew M, Thomas S: Psychosocial risk factors in home and community settings and their associations with population health and health inequalities: a systematic meta-review. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 239-10.1186/1471-2458-8-239.

Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG: Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 56 (6): 1321-1333. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4.

Adler N: When one's main effect is another's error: Material vs. psychosocial explanations of health disparities. A commentary on Macleod et al., "Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men" (61(9), 2005, 1916-1929). Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63 (4): 846-850. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.018.

Zapf D, Dormann C, Frese M: Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: a review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996, 1 (2): 145-169.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, (Eds): Using Multivariate Statistics. 1996, New York: Harper Collins

Wheaton B: The twain meet: distress, disorder and the continuing conundrum of categories (comment on Horwitz). Health (London, England : 1997). 2007, 11 (3): 303-319.

Horwitz AV: Distinguishing distress from disorder as psychological outcomes of stressful social arrangements. Health (London, England : 1997). 2007, 11 (3): 273-289.

Petticrew M, Roberts H: Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. 2006, Cornwall, UK: Blackwell Publishing

QSR International Pty Ltd: NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 2000, Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2

SPSS Inc.: SPSS Base 15.0 for Windows User's Guide. 2006, Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.

Turner JR, Wheaton B: Checklist measurement of stressful life events. Measuring stress: a guide for health and social scientists. Edited by: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. 1995, New York: Oxford University Press, 29-58.

Wells GA, Brodsky L, O'Connell D, Shea B, Henry D, Mayank S, Tugwell P: An evaluation of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale: an assessment tool for evaluating the quality of non-randomized studies. XI Cochrane Colloquium: Evidence, Health Care & Culture. 2003, Barcelona, Spain, 26:

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 3rd Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics: July 3-5 2000. 2000, Oxford, UK

van der Windt DA, Thomas E, Pope DP, de Winter AF, Macfarlane GJ, Bouter LM, Silman AJ: Occupational risk factors for shoulder pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2000, 57 (7): 433-442. 10.1136/oem.57.7.433.

Ostry A, Maggi S, Tansey J, Dunn J, Hershler R, Chen L, Hertzman C: The impact of psychosocial and physical work experience on mental health: a nested case control study. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2006, 25 (2): 59-70.

Wickrama KAS, Lorenz FO, Fang S, Abraham WT, Elder GH: Gendered trajectories of work control and health outcomes in the middle years: a perspective from the rural market. J Aging Health. 2005, 17 (6): 779-806. 10.1177/0898264305279868.

Griffin JM, Fuhrer R, Stansfeld SA, Marmot M: The importance of low control at work and home on depression and anxiety: do these effects vary by gender and social class?. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 54 (5): 783-798. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00109-5.

Niedhammer I, Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Bugel I, David S: Psychosocial factors at work and subsequent depressive symptoms in the GAZEL cohort. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998, 24 (3): 197-205.

Bromet EJ, Dew MA, Parkinson DK, Schulberg HC: Predictive effects of occupational and marital stress on the mental health of a male workforce. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1988, 9 (1): 1-13.

Barnett RC, Brennan RT: Change in job conditions and change in psychological distress within couples: a study of crossover effects. Women's health (Hillsdale, NJ). 1998, 4 (4): 313-339.

Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Davey Smith G, Marmot M: Future uncertainty and socioeconomic inequalities in health: the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 57 (4): 637-646. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00406-9.

Mausner-Dorsch H, Eaton WW: Psychosocial work environment and depression: epidemiologic assessment of the demand-control model. Am J Public Health. 2000, 90 (11): 1765-1770. 10.2105/AJPH.90.11.1765.

Bildt C, Michelsen H: Gender differences in the effects from working conditions on mental health: A 4-year follow-up. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2002, 75 (4): 252-258. 10.1007/s00420-001-0299-8.

Brown G, Bifulco A: Motherhood, employment and the development of depression: a replication of a finding?. Br J Psychiatry. 1990, 156: 169-179. 10.1192/bjp.156.2.169.

Houkes I, Janssen PPM, de Jonge J, Bakker AB: Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, emotional exhaustion and turnover intention: a multisample longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2003, 76: 427-450. 10.1348/096317903322591578.

Muntaner C, Li Y, Xue X, Thompson T, O'Campo P, Chung H, Eaton WW: County level socioeconomic position, work organization and depression disorder: a repeated measures cross-classified multilevel analysis of low-income nursing home workers. Health Place. 2006, 12 (4): 688-700. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.09.004.

Muntaner C, Li Y, Xue XN, Thompson T, Chung HJ, O'Campo P: County and organizational predictors of depression symptoms among low-income nursing assistants in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63 (6): 1454-1465. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.042.

Perry-Jenkins M, Goldberg AE, Pierce CP, Sayer AG: Shift work, role overload, and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007, 69 (1): 123-138. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00349.x.

Brand JE, Warren JR, Carayon P, Hoonakker P: Do job characteristics mediate the relationship between SES and health? Evidence from sibling models. Soc Sci Res. 2007, 36 (1): 222-253. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.11.004.

Fernandez ME, Mutran EJ, Reitzes DC: Moderating the effects of stress on depressive symptoms. Res Aging. 1998, 20 (2): 163-182. 10.1177/0164027598202001.

Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Newman K, Stansfeld SA, Marmot M: Self-reported job insecurity and health in the Whitehall II study: potential explanations of the relationship. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 60 (7): 1593-1602. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.006.

Matthews S, Power C: Socio-economic gradients in psychological distress: a focus on women, social roles and work-home characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 54 (5): 799-810. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00110-1.

Matthews S, Power C, Stansfeld S: Psychological distress and work and home roles: a focus on socio-economic differences in distress. Psychol Med. 2001, 31 (4): 725-736.

Melchior M, Caspl A, Milne BJ, Danese A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE: Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol Med. 2007, 37 (8): 1119-1129. 10.1017/S0033291707000414.

Power C, Stansfeld S, Matthews S, Manor O, Hope S: Childhood and adulthood risk factors for socio-economic differentials in psychological distress: evidence from the 1958 British birth cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 55 (11): 1989-2004. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00325-2.

Waldenstrom K, Ahlberg G, Bergman P, Forsell Y, Stoetzer U, Waldenstrom M, Lundberg I: Externally assessed psychosocial work characteristics and diagnoses of anxiety and depression. Occup Environ Med. 2008, 65 (2): 90-97. 10.1136/oem.2006.031252.

Bonde JP, Mikkelsen S, Andersen JH, Fallentin N, Baelum J, Svendsen SW, Thomsen JF, Frost P, Kaergaard A, Group PHS: Understanding work related musculoskeletal pain: does repetitive work cause stress symptoms?. Occup Environ Med. 2005, 62 (1): 41-48. 10.1136/oem.2003.011296.

Nakao M, Nishikitani M, Shima S, Yano E: A 2-year cohort study on the impact of an Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) on depression and suicidal thoughts in male Japanese workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007, 81 (2): 151-157. 10.1007/s00420-007-0196-x.

Virtanen P, Oksanen T, Kivimaki M, Virtanen M, Pentti J, Vahtera J: Work stress and health in primary health care physicians and hospital physicians. Occup Environ Med. 2008, 65 (5): 364-366. 10.1136/oem.2007.034793.

Burke RJ, Greenglass E: A longitudinal study of psychological burnout in teachers. Human Relations; studies towards the integration of the social sciences. 1995, 48 (2): 187-202.

Burke RJ, Greenglass ER: A longitudinal examination of the Cherniss model of psychological burnout. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 40 (10): 1357-1363. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00267-W.

Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper M: Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: a four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1997, 70 (4): 325-335.

Fusilier M, Manning MR: Psychosocial predictors of health status revisited. J Behav Med. 2005, 28 (4): 347-358. 10.1007/s10865-005-9002-y.

Glickman L, Tanaka JS, Chan E: Life events, chronic strain, and psychological distress: longitudinal causal models. J Community Psychol. 1991, 19 (4): 283-305. 10.1002/1520-6629(199110)19:4<283::AID-JCOP2290190402>3.0.CO;2-5.

Greenglass ER, Fiksenbaum L, Burke RJ: The relationship between social support and burnout over time in teachers. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1994, 9 (2): 219-230.

Innstrand ST, Langballe EM, Espnes GA, Falkum E, Aasland OG: Positive and negative work--family interaction and burnout: a longitudinal study of reciprocal relations. Work and Stress. 2008, 22 (1): 1-15. 10.1080/02678370801975842.

Kinnunen U, Geurts S, Mauno S: Work-to-family conflict and its relationship with satisfaction and well-being: a one-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Work and Stress. 2004, 18 (1): 1-22. 10.1080/02678370410001682005.

Michelsen H, Bildt C: Psychosocial conditions on and off the job and psychological ill health: depressive symptoms, impaired psychological wellbeing, heavy consumption of alcohol. Occup Environ Med. 2003, 60 (7): 489-496. 10.1136/oem.60.7.489.

O'Campo P, Eaton WW, Muntaner C: Labor market experience, work organization, gender inequalities and health status: results from a prospective analysis of US employed women. Soc Sci Med. 2004, 58 (3): 585-594. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00230-2.

Olstad R, Sexton H, Sogaard AJ: The Finnmark study. A prospective population study of the social support buffer hypothesis, specific stressors and mental distress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001, 36 (12): 582-589. 10.1007/s127-001-8197-0.

Orth-Gomer K, Leineweber C: Multiple stressors and coronary disease in women: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. Biol Psychol. 2005, 69 (1 SPEC. ISS.): 57-66.

Rose G, Kumlin L, Dimberg L, Bengtsson C, Orth-Gomer K, Cai X: Work-related life events, psychological well-being and cardiovascular risk factors in male Swedish automotive workers. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England). 2006, 56 (6): 386-392.

Shimazu A, Schaufeli WB: Does distraction facilitate problem-focused coping with job stress? A 1 year longitudinal study. J Behav Med. 2007, 30 (5): 423-434. 10.1007/s10865-007-9109-4.

Taris TW: The mutual effects between job resources and mental health: a prospective study among Dutch youth. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1999, 125 (4): 433-450.

Tokuyama M, Nakao K, Seto M, Watanabe A, Takeda M: Predictors of first-onset major depressive episodes among white-collar workers. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003, 57 (5): 523-531. 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01158.x.

Wang J: Work stress as a risk factor for major depressive episode(s). Psychol Med. 2005, 35 (6): 865-871. 10.1017/S0033291704003241.

Ryan P, Anczewska M, Laijarvi H, Czabala C, Hill R, Kurek A: Demographic and situational variations in levels of burnout in European mental health services: a comparative study. Diversity in Health and Social Care. 2007, 4 (2): 101-112.

Suzuki E, Kanoya Y, Katsuki T, Sato C: Assertiveness affecting burnout of novice nurses at university hospitals. Japan Journal of Nursing Science. 2006, 3 (2): 93-105. 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2006.00058.x.

Gelsema TI, van der Doef M, Maes S, Janssen M, Akerboom S, Verhoeven C: A longitudinal study of job stress in the nursing profession: causes and consequences. J Nurs Manag. 2006, 14 (4): 289-299. 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00635.x.

Ferrie JE, Head J, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG, Kivimäki M: Injustice at work and incidence of psychiatric morbidity: the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med. 2006, 63 (7): 443-450. 10.1136/oem.2005.022269.

Rydstedt L, Ferrie J, Head J: Is there support for curvilinear relationships between psychosocial work characteristics and mental well-being? Cross-sectional and long-term data from the Whitehall II study. Work and Stress. 2006, 20 (1): 6-20. 10.1080/02678370600668119.

De Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM: The relationships between work characteristics and mental health: examining normal, reversed and reciprocal relationships in a 4-wave study. Work and Stress. 2004, 18 (2): 149-166. 10.1080/02678370412331270860.

Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG: Effects of chronic job insecurity and change in job security on self reported health, minor psychiatric morbidity, physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002, 56 (6): 450-454. 10.1136/jech.56.6.450.

Estryn-Behar M, van der Eijden B, Camerino D, Fry C, Le Nezet O, Conway PM, Hasselhorn HM: Violence risks in nursing - Results from the European 'NEXT' study. Occup Med. 2008, 58 (2): 107-114. 10.1093/occmed/kqm142.

Janssen N, Nijhuis FJN: Associations between positive changes in perceived work characteristics and changes in fatigue. J Occup Environ Med. 2004, 46 (8): 866-875. 10.1097/01.jom.0000135608.82039.fa.

Kalimo R, Pahkin K, Mutanen P: Work and personal resources as long-term predictors of well-being. Stress and Health. 2002, 18 (5): 227-234. 10.1002/smi.949.

Shigemi J, Mino Y, Ohtsu T, Tsuda T: Effects of perceived job stress on mental health. A longitudinal survey in a Japanese electronics company. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000, 16 (4): 371-376. 10.1023/A:1007646323031.

Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG: Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med. 1999, 56 (5): 302-307. 10.1136/oem.56.5.302.

van Vegchel N, de Jonge J, Soderfeldt M, Dormann C, Schaufeli W: Quantitative versus emotional demands among Swedish human service employees: moderating effects of job control and social support. International Journal of Stress Management. 2004, 11 (1): 21-40.

Dormann C, Zapf D: Social support, social stressors at work, and depressive symptoms: testing for main and moderating effects with structural equations in a three-wave longitudinal study. J Appl Psychol. 1999, 84 (6): 874-884.

Dormann C, Zapf D: Social stressors at work, irritation, and depressive symptoms: accounting for unmeasured third variables in a multi-wave study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2002, 75 (1): 33-58. 10.1348/096317902167630.

Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Head J, Ferrie J, et al: Work and psychiatric disorder in the Whitehall II study. J Psychosom Res. 1997, 43 (1): 73-81. 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00001-9.

Houkes I, Janssen PPM, de Jonge J, Bakker AB: Personality, work characteristics, and employee well-being: a longitudinal analysis of additive and moderating effects. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003, 8 (1): 20-38.

de Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM: Effects of stable and changing demand-control histories on worker health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002, 28 (2): 94-108.

Garst H, Frese M, Molenaar PC: The temporal factor of change in stressor-strain relationships: a growth curve model on a longitudinal study in east Germany. J Appl Psychol. 2000, 85 (3): 417-438.

Johnson JV, Hall EM, Ford DE, Mead LA, Levine DM, Wang NY, Klag MJ: The psychosocial work environment of physicians. The impact of demands and resources on job dissatisfaction and psychiatric distress in a longitudinal study of Johns Hopkins Medical School graduates. J Occup Environ Med. 1995, 37 (9): 1151-1159. 10.1097/00043764-199509000-00018.

Houkes I, Winants Y, Twellaar M: Specific determinants of burnout among male and female general practitioners: a cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2008, 81: 249-276. 10.1348/096317907X218197.

De Raeve L, Jansen NWH, Kant I: Health effects of transitions in work schedule, workhours and overtime in a prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007, 33 (2): 105-113.

de Lange AH, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM: Different mechanisms to explain the reversed effects of mental health on work characteristics. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005, 31 (1): 3-14.

de Jonge J, Dormann C, Janssen PPM, Dollard MF, Landeweerd JA, Nijhuis FJN: Testing reciprocal relationships between job characteristics and psychological well-being: a cross-lagged structural equation model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2001, 74: 29-46. 10.1348/096317901167217.

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Sixma HJ, Bosveld W, Van Dierendonck D: Patient demands, lack of reciprocity, and burnout: a five-year longitudinal study among general practitioners. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2000, 21 (4): 425-441. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200006)21:4<425::AID-JOB21>3.0.CO;2-#.

Smith P, Frank J, Bondy S, Mustard C: Do changes in job control predict differences in health status? Results from a longitudinal national survey of Canadians. Psychosom Med. 2008, 70 (1): 85-91.

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Stamm M, Siegrist J, Buddeberg C: Work stress and reduced health in young physicians: Prospective evidence from Swiss residents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008, 82 (1): 31-38. 10.1007/s00420-008-0303-7.

Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Elovainio M, Virtanen M, Siegrist J: Effort-reward imbalance, procedural injustice and relational injustice as psychosocial predictors of health: complementary or redundant models?. Occup Environ Med. 2007, 64 (10): 659-665. 10.1136/oem.2006.031310.

Rugulies R, Bültmann U, Aust B, Burr H: Psychosocial work environment and incidence of severe depressive symptoms: prospective findings from a 5-year follow-up of the Danish Work Environment Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 163 (10): 877-887. 10.1093/aje/kwj119.

Ylipaavalniemi J, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Virtanen M, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Vahtera J: Psychosocial work characteristics and incidence of newly diagnosed depression: a prospective cohort study of three different models. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (1): 111-122. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.038.

Borritz M, Bültmann U, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Villadsen E, Kristensen TS: Psychosocial work characteristics as predictors for burnout: findings from 3-year follow up of the PUMA study. J Occup Environ Med. 2005, 47 (10): 1015-1025. 10.1097/01.jom.0000175155.50789.98.

Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L: Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med. 2003, 60 (10): 779-783. 10.1136/oem.60.10.779.

Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Ferrie JE: Organisational justice and health of employees: prospective cohort study... including commentary by Theorell T. Occup Environ Med. 2003, 60 (1): 27-34. 10.1136/oem.60.1.27.

Godin I, Kittel F, Coppieters Y, Siegrist J: A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health. 2005, 5 (67):

Wang J: Perceived work stress and major depressive episodes in a population of employed Canadians over 18 years old. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004, 192 (2): 160-163. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000110242.97744.bc.

Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Virtanen M, Stansfeld SA: Association between organizational inequity and incidence of psychiatric disorders in female employees. Psychol Med. 2003, 33 (2): 319-326. 10.1017/S0033291702006591.

Paterniti S, Niedhammer I, Lang T, Consoli S: Psychosocial factors at work, personality traits and depressive symptoms: longitudinal resulst from the GAZEL study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002, 181 (2): 111-117.

Eriksen W, Tambs K, Knardahl S: Work factors and psychological distress in nurses' aides: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 290-10.1186/1471-2458-6-290.

Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Martikainen P, Stansfeld SA, Smith GD: Job insecurity in white-collar workers: toward an explanation of associations with health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2001, 6 (1): 26-42.

Clays E, De Bacquer D, Eynen FL, Kornitzer M, Kittel F, De Backer G: Job stress and depression symptoms in middle-aged workers - prospective results from the Belstress study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007, 33 (4): 252-259.

Bültmann U, Kant I, van den Brandt PA, Kasl SV: Psychosocial work characteristics as risk factors for the onset of fatigue and psychological distress: prospective results from the Maastricht Cohort Study. Psychol Med. 2002, 32 (2): 333-345.

Kawakami N, Haratani T, Araki S: Effects of perceived job stress on depressive symptoms in blue-collar workers of an electrical factory in Japan. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992, 18 (3): 195-200.

Kuper H, Singh-Manoux A, Siegrist J, Marmot M: When reciprocity fails: effort-reward imbalance in relation to coronary heart disease and health functioning within the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med. 2002, 59 (11): 777-784. 10.1136/oem.59.11.777.

Cheng Y, Kawachi I, Coakley EH, Schwartz J, Colditz G: Association between psychosocial work characteristics and health functioning in American women: prospective study. Br Med J. 2000, 320 (7247): 1432-1436. 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1432.

Reifman A, Biernat M, Lang EL: Stress, social support, and health in married professional women with small children. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991, 15 (3): 431-445. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00419.x.

Pelfrene E, Clays E, Moreau M, Mak R, Vlerick P, Kornitzer M, De Backer G: The job content questionnaire: methodological considerations and challenges for future research. Archives of Public Health. 2003, 61 (1-2): 53-74.

Bourbonnais R, Comeau M, Vezina M: Job strain and evolution of mental health among nurses. J Occup Health Psychol. 1999, 4 (2): 95-107.

Väänänen A, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Kivimäki M: Sources of social support as determinants of psychiatric morbidity after severe life events: prospective cohort study of female employees. J Psychosom Res. 2005, 58 (5): 459-467. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.10.006.

Plaisier I, de Bruijn JG, de Graaf R, ten Have M, Beekman AT, Penninx BW: The contribution of working conditions and social support to the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders among male and female employees. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64 (2): 401-410. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.008.

Ala-Mursula L, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Kivimäki M: Effect of employee worktime control on health: a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2004, 61 (3): 254-261. 10.1136/oem.2002.005983.

Woodward CA, Shannon HS, Cunningham C, McIntosh J, Lendrum B, Rosenbloom D, Brown J: The impact of re-engineering and other cost reduction strategies on the staff of a large teaching hospital: a longitudinal study. Med Care. 1999, 37 (6): 556-569. 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00005.

Burke RJ, Greenglass ER, Schwarzer R: Predicting teacher burnout over time: Effects of work stress, social support, and self-doubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1996, 9 (3): 261-275. 10.1080/10615809608249406.

Revicki DA, Whitley TW, Gallery ME, Jackson Allison E: Impact of work environment characteristics on work-related stress and depression in emergency medicine residents: a longitudinal study. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology. 1993, 3: 273-284. 10.1002/casp.2450030405.

Shields M: Shift work and health. Health Rep. 2002, 13 (4): 11-33.

Fuhrer R, Stansfeld SA, Chemali J, Shipley MJ: Gender, social relations and mental health: prospective findings from an occupational cohort (Whitehall II study). Soc Sci Med. 1999, 48 (1): 77-87. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00290-1.

Shields M: Long working hours and health. Health Rep. 1999, 11 (2): 33-47.

Smith PM, Frank JW, Mustard CA, Bondy SJ: Examining the relationships between job control and health status: a path analysis approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008, 62 (1): 54-61. 10.1136/jech.2006.057539.

Stansfeld SA, Bosma H, Hemingway H, Marmot MG: Psychosocial work characteristics and social support as predictors of SF-36 health functioning: the Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med. 1998, 60 (3): 247-255.

Mair C, Roux AVD, Galea S: Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008, 62 (11): 940-U921.

De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SRA: Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59 (8): 619-627. 10.1136/jech.2004.029678.

Lancee B, ter Hoeven CL: Self-rated health and sickness-related absence: the modifying role of civic participation. Soc Sci Med. 2010, 70 (4): 570-574. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.032.

Twenge JM: A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2010, 25 (2): 201-210. 10.1007/s10869-010-9165-6.

Sanderson S, Tatt LD, Higgins JPT: Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007, 36 (3): 666-676. 10.1093/ije/dym018.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/439/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a postdoctoral fellowship granted to Nancy Beauregard by the University of Montreal Research Institute in Public Health as well as part of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (2000607MHF-164381-MHF-CFCA-155960). The authors would like to cordially thank Robert Sullivan and Heather Burnett for their assistance in English revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NB planned, collected, and analysed the data, and is lead author. AM and MEB assisted in the conceptual and verification stages of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2010_3255_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Search Strategy. It contains all the details for the search strategy performed for the research article. (DOC 97 KB)

12889_2010_3255_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: Critical Appraisal. It contains a table entitled 'Additional file 2. Items considered for the critical appraisal'. This table includes all the items upon which the methodological and conceptual quality of the included studies for the systematic review were critically appraised. (DOC 46 KB)

12889_2010_3255_MOESM3_ESM.DOC

Additional file 3: Strength of Evidence. It contains a figure entitled 'Additional file 3. Strength of evidence assessment'. This figure illustrates the decision process followed in the assessment of the strength of evidence. (DOC 45 KB)

12889_2010_3255_MOESM4_ESM.DOC

Additional file 4: Moose. It contains a table entitled 'Additional file 4. MOOSE Checklist'. This table includes all items upon which an evaluation of the research article was based considering the MOOSE evaluation tool. (DOC 64 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Beauregard, N., Marchand, A. & Blanc, ME. What do we know about the non-work determinants of workers' mental health? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 11, 439 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-439

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-439