Abstract

Background

The feasibility and acceptability of partner notification (PN) for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in developing countries was assessed through a comprehensive literature review, to help identify future intervention needs.

Methods

The Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar databases were searched to identify studies published between January 1995 and December 2007 on STI PN in developing countries. A systematic review of the research extracted information on: (1) willingness of index patients to notify partners; (2) the proportion of partners notified or referred; (3) client-reported barriers in notifying partners; (4) infrastructure barriers in notifying partners; and (5) PN approaches that were evaluated in developing countries.

Results

Out of 609 screened articles, 39 met our criteria. PN outcome varied widely and was implemented more often for spousal partners than for casual or commercial partners. Reported barriers included sociocultural factors such as stigma, fear of abuse for having an STI, and infrastructural factors related to the limited number of STD clinics, and trained providers and reliable diagnostic methods. Client-oriented counselling was found to be effective in improving partner referral outcomes.

Conclusions

STD clinics can improve PN with client-oriented counselling, which should help clients to overcome perceived barriers. The authors speculate that well-designed PN interventions to evaluate the impact on STI prevalence and incidence along with cost-effectiveness components will motivate policy makers in developing countries to allocate more resources towards STI management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Partner Notification (PN) for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has been recommended as an important step in STI management to help interrupt transmission of infections, prevent potential re-infection, and prevent complications [1–4]. PN provides an opportunity to make index patients aware of risk-reduction strategies for avoiding STIs [5], enables earlier diagnosis for partners, motivate behavior change in clients and partners, and reduce the burden of disease in communities [6]. Three main approaches to PN have been suggested for STIs [7]: (1) provider-oriented notification methods that use third parties (usually health-care personnel serving as "contact tracers"); (2) patient-oriented notification methods that use index patients notify their partners, with or without the medication to actually treat the partner for the putative infection or infectious exposure [8], and (3) a mixed approach of contact-notification that engages the index patients to notify their partners, with an understanding that health-care personnel will notify those partners who do not present for treatment within a given time [7].

PN has come a long way since its inception in the 19th century; however, it still has several issues in terms of efficacy, priority setting, adaptation of new approaches and cost effectiveness [4]. PN is not a standalone program in STI control and management, it almost always work as a complementary program with other routine activities including screening and treatment. There is wide variation in the policy and practice of PN approaches around the world [9]. No single PN approach has ever been found to be effective for all settings because of likely variations in STI rates and care structures. PN strategies that are effective and feasible in developed countries may not be applicable for developing countries [10]. Provider-oriented notification was found to be effective in reaching partners of people with STIs [11, 12] but the evidence was mainly drawn from studies conducted in developed countries and also concurrent with the fact that provider- based notification is more expensive than patient-based approaches [13]. These high costs preclude provision of provider-oriented notification strategies for many developing countries and limit their application even where promulgated. Patient-oriented PN intervention strategies including patient-centered counseling [14] and patient-delivered medication were reported to increase partner referral in Africa [15]. However, implementation of STI PN programs remains limited in developing countries due to inadequate resources, poor infrastructure for diagnosis and management of STIs as well as social stigma [16–18]. Stigma and discrimination against people with STI undermine their ability to seek care, and their willingness to notify spouses or other partners of their STI infection status [19].

We sought to explore both the feasibility and the acceptability of PN in STI management in developing countries both from the demand side and the supply side perspectives. Our developing country focus acknowledges that PN approaches and outcomes are influenced by health system characteristics and resource limitations, legislation and policy, socio-cultural and socioeconomic factors, and stigma issues of importance to patients and their partners [10]. By developing country we referred to the low, lower middle and upper middle income countries based on World Bank's classification of economies based on gross national income (GNI) per capita [20]. We included only the PN studies on curable STIs (syphilis or gonorrhea or chlamydia or trichomoniasis), because HIV is not curable and there are special considerations for long-term support of behavioral change and access to medications. We targeted the following issues as a proxy to understand feasibility and acceptability of PN in developing countries: (1) Willingness of index patients to self-notify partners; (2) The proportion of partners notified or referred; (3) Client-reported barriers in notifying partners; (4) Staff or investigator-reported infrastructure barriers in notifying partners; and (5) PN approaches that were evaluated in developing countries.

Methods

Search Strategy

Three electronic bibliographic databases including Medline (via PubMed), Embase (via Scirus), and Google Scholar were systematically searched to identify relevant published articles on PN of STIs in developing countries. The reference lists of potentially relevant articles were examined for additional references and the "related" search key in PubMed was used from highly relevant articles to search for additional publications. We limited our automated searches to articles in English published between January 1995 and December 2007. Articles published before 1995 were not included as earlier findings may be less relevant to more recent PN intervention approaches and their outcomes, due to changes in STI diagnostics, medications, health care policies, and societal attitudes [21]. To identify a comprehensive set of possible search terms of PN for STIs, we consulted indexed terms in titles, key words and abstracts of published journal articles in this area. We searched eligible citations using (sexually transmitted infection or sexually transmitted disease) or (STD or STI) or (syphilis or gonorrhea or chlamydia or trichomoniasis), and (PN or partner referral or partner management or partner tracing or contact tracing or STI management) as key words. Searches were modified for Embase and Google Scholar databases to conform to their search structures. The first author exclusively performed searches under direct supervision of the last author (SK). Searches were updated through March 30, 2008.

Screening of articles

In order to select a final set of articles for review, we examined the title and abstract of the articles and included articles if: (1) they were relevant to at least one of the five PN related issues highlighted above, (2) if the article was published from primary data, (3) if the data derived from a population in developing countries [20], and (4) if the articles dealt with PN of common curable STIs (gonorroea, chlamydia, syphilis, and trichomoniasis).

Data abstraction

From each selected article, we abstracted information using a pre-specified 14 item data abstraction form. Abstracted data included authors name, year, study design, country, population covered, outcomes measures and major findings. Symmetrical to our review questions; quantitative outcome data were abstracted to determine the proportion of patients intending to self notify partners, the proportion of partners notified, and the proportion of partners reporting to the clinics for evaluation and treatment. We also synthesized qualitative textual information on barriers of notifying partners as reported by the clients. We further examined infrastructural barriers related to implementation of PN programs as reported by the program staff and/or the report authors. We considered the following criteria to assess the quality and relevance of the reviewed studies, whether a study: (1) had clear inclusion and exclusion criteria for study subjects; (2) followed a study design that allow generalizability of the studied subjects who were representative of a broader population at risk for STIs; and (3) used statistical tests point estimates with confidence intervals or p-values and adjusted for confounding and interaction when necessary. This quality assessment was done for our review purposes, not to include or exclude studies per se. "Higher-quality" studies were those having objectively measured PN outcome data, study subjects were randomly assigned and used proper statistical methods for analyzing data. "Moderate-quality" studies contained PN outcomes that were measured, but had study designs limiting the scope of generalizablity. "Lower-quality" studies had no clear indication of how study subject were recruited and outcomes were measured or reported only textual information on PN outcomes (Table 1 and 2).

Results

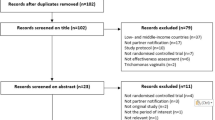

From 609 articles (474 unique: not overlapped across search data bases), 372 were from Medline, 138 from Embase (Scirus), and 99 from Google scholar data base. After the selection process (Figure 1), we identified 39 articles for this review, 28 from Africa, 6 from Asia and 5 from Latin American or Caribbean countries (Table 1 and 2). Studies had diverse study designs and populations. Only three studies were randomized trials [14, 15, 22]. Five studies collected data from women in antenatal clinics [23–26] or in home-based STI screening programs [27]. Four studies were pre-test post-test evaluation [10, 27–30], five studies solely utilized qualitative design for data collection [15, 24, 31–33]. Other studies had either cross sectional design, observation or descriptive design and prospective follow-up design (Table 1 and 2). Two studies focused on men in STD clinics in China [19, 34] and three studies collected data from STI service providers [30, 35, 36]. Other population covered in the studies included men and women from general population, pregnant women in antenatal clinics and medicine sellers. According to our quality assessment criteria, 32 articles were found to be of moderate quality, 7 were lower uality and none satisfy to be graded as higher quality.

Willingness of index patients to self-notify partners

Seven studies described the willingness of index patients to self-notify their sexual partners (Table 3). Majority of the index patients expressed their willingness to self-notify their partners as indicated by their willingness based on a specific question in the survey or through accepting referral cards for their partners. The proportion raging from 58% to 93% [[14, 23, 37–40], except for one study reported that 77% of 406 men expressed their unwillingness to report their STI status to their spouse due to the associated stigma [19]. Motivation of index patients to self-notify their partners differed for men and women; many women felt certain that their husbands were the source of infection and therefore needed treatment. Pregnant women were particularly motivated to notify their spousal partner because they are concerned about infection risk to their fetus/baby [14]. Some women in Bolivia reported notifying their husbands to get information on the source of the STI and address infidelity in their marriage [24]. Men having STIs in Kenya reported notifying their wives to avoid infertility in themselves or in their wives, lack of condom use with wives as motivating factor for notification, fearing the likely spread of infection to their wives and their own reinfection [14].

Proportion of partners notified or referred

Most studies report on PN outcomes as the proportion of partners notified and/or the proportion of partners reporting back to the study clinics. Nine studies reported the proportion of partners actually received treatment [16, 27, 33, 39, 41–45]. The median proportion of partners notified in the selected studies who reported quantitative estimates was 54% (range, 0% to 94%) depending on the type of partner and the means of verification (Table 3). These extremes were found in one study, where 0% notification for casual partners, but 94% for spousal partners [25]. The proportion of partners actually referred to the clinics was, 20% for female partners of male STI patients in China [34], 30% for male partners of women diagnosed with STIs in prenatal screening in Haiti [23] and 34% of the partners received treatment in patient oriented notification method in Zambia [22]. There was little correlation between the willingness of patients to notify their partners and their reported success; in one study 86% of patients were willing to notify, but only 30% of partners were reported as notified [23]. In another 58% of patients were willing to notify and 45% of partners were reported as notified [38].

Client reported barriers in notifying partners

Five studies investigated whether index patients faced barriers to notifying partners [14, 24, 26, 34, 40]. Major perceived barriers in Peru included embarrassment, fear of rejection, stigma associated to the disease and difficulty in locating casual partners [26]. The main barriers for women to notify partners included: (1) their husband worked in a different town; (2) fear that their husband will accuse them of being the source of the STI; and (3) fear of divorce [14, 26]. Married men reported barriers to notifying their wives being: (1) the wife lived in a rural area; (2) embarrassment; (3) fear of loss of respect; and (4) fear of disharmony in the family. Women mostly feared that their extramarital relationships would be revealed and/or they feared that they would be treated as the source of their husband's infection [40]. For men, the main barriers were fears of being considered unfaithful, leading to separation or divorce. Two major barriers for notifying casual and commercial partners included (1) being partners who were not traceable and (2) men did not care to notify them since they had no further plan to have a sexual relationship with the casual partner in question [14]. Women who had non-spousal partners indicated that they depended upon them financially and could not risk annoying them for fear of losing material support.

Staff or investigator reported infrastructure barriers in notifying partners

Most common structural barriers reported in the studies included inadequate staff and lack of accurate, affordable diagnostic services. Inadequately trained staff in STD clinics was one of the major barriers making provider-oriented referrals difficult; increasing the work load of already overburdened health care providers was deemed unrealistic [16]. The socioeconomic profile of the study participants was considered a barrier to PN in some settings in that the population was often mobile, and lacked access to mail, telephones, or traceable addresses [16]. Lack of valid, user-friendly, and affordable STI diagnostic methods was also mentioned as structural barriers for PN, while syndromic management approaches mostly used in developing countries were reported to identify false positive cases leading to medicate people who do not need it[27, 37]. Inadequate resources and poor availability of trained staff were reported as barriers of PN, especially provider-oriented notification in already overburdened health care systems [38]. Lacking of necessary counselor in the STD clinics was specifically mentioned as barrier to PN programs implementation [19, 31].

PN approaches that were evaluated in developing countries

Five intervention studies evaluated PN outcomes in developing countries [10, 14, 18, 22, 27]. Two randomized trials investigated effectiveness of client-centered counseling on PN outcomes [14, 18]. The trial in Zimbabwe found that index patients in the counseling arm were more likely to report notifying their partners compared to the controls [92% vs. 67%, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 4.1; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3-13.2; p < 0.001] adjusted for age, gender, employment status, and type of partners[14]. The trial in Zambia reported that an average of 1.8 partners per infected man were treated in the counseling-for-notification group compared to 1.2 in the control group (p < 0.001), but they did not find any significant effect of PN counseling among infected women [18]. One randomized trial investigated if patient-delivered medication was effective in treating partners of STI patients compared to patient-based referral alone. Medicines were reported as delivered to 74% of the partners in the patient-delivered medication group compared to verified successful referral to the clinics in just 34% of the patient-based partner referral group [risk ratio (RR) 2.44; 95% CI 1.95-3.07; p < 0.001] [22]. When given a choice, 85% chose patient-delivered partner medication while only 13% chose patient- based referral approach in one South African study [27]. Another South African study investigated if video-based health education would be effective in improving partner referral; the rate of contact cards returned per index patient was 0.27 in the intervention phase, compared with 0.20 in the control phase an increase that may have been due to chance [10].

Discussion

Patient-oriented PN approaches were preferred methods in the developing countries as per our review studies, which is in accordance with the WHO recommendation that patient-based notification should be the first step for developing countries [6]. Counselling to index STI patients on PN was found to be effective in increasing partner referral in studies conducted in Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Kenya [14, 16, 18]. This simple intervention is reasonable for developing countries for several reasons: (1) overworked health care providers dealing with a large number of STI patients will not be suitable for provider-oriented notifications; (2) counselling services were well received by clients; (3) counselling for patient-oriented notifications can be easily integrated into public and private sector clinics; and (4) counselling costs will be lower than physician counselling [14]. The major challenge however, to this intervention is that counsellors are not available in health centres in most developing countries. A health system audit in rural South Africa, one of sub-Saharan Africa's middle income nations, reported that almost half of their study clinics did not have counsellors in their STD clinics [31]. Similarly, in China most STD clinics do not provide counselling services to their patients [19].

Randomized trial investigated patient-delivered partner medications approach in developing countries suggested that this approach was more effective in reaching sexual partners of index STI patients for treatment compared to patient-oriented notification alone [22]. Some other PN studies conducted in China, Kenya, South Africa, and Peru recommended further evaluation of the effectiveness of partner-delivered treatment approaches in developing countries because of low number of partners known to receive treatment for STIs after notification justify potential importance of expedited partner-facilitated therapy programs [16, 27, 26, 45]. However, implementation of patient-delivered treatment approaches may conflict with medical practice guidelines in some countries, since antibiotics are given to patients to give to their sexual contacts without evaluation by a clinician. It is uncertain whether the treatments will reach the intended target patient, nor whether that person actually needs the therapy. A decision analysis model in a developing country context would be helpful to quantify the relative costs and benefits; a model crafted for high-cost, comparatively low prevalence circumstances suggested PN to be cost-effective even in the United States [46].

Major barriers to successful PN from the patient's perspective were grounded in cultural and psychosocial issues. The stigma associated with STIs discourages patients from discussing their infections and sexual behaviours with their partners, especially given extramarital sexual relationships [26, 47]. Gender, power structure, and partner type were important in PN intentions and practices [24]. Fear of abuse and rejection resulting from partner referral was found to be major barriers, especially for women [14, 26]. Notification of non-spouse partners by index patients was low both for men and women. Women who had non-spouse partners indicated that these partners were often concurrent and that they depended upon them financially. Economic vulnerability of women must be considered in the design of PN in developing countries, given women's difficulties in negotiating safer sex and broaching sexual matters [48].

STI diagnoses are predominantly based on syndromic approaches in most developing countries leaving possibilities of over diagnosis, and overmedication [49, 50]. PN in such cases could result in unnecessary social harm to the patients, resulting partner violence, separation, and social isolation [27]. Weak health systems with under-capacitated STD clinics and limited personnel (including doctors, nurses and counsellors) are unlikely to emphasize PN when funds for medicines and other supplies are insufficient [16]. Exclusive facilities for STI/HIV management in developing countries are rare; STI clinical services are often merged with skin, other reproductive health and family planning services. Inadequate attention may be devoted to the STI patients when health care providers are overloaded with many other patients. Clinicians are inadequately trained in STI management and may be unmotivated to support PN efforts [51].

A formal meta-analysis was not feasible for this topic. There were substantial variations in study designs and in the populations they studied. Many approaches were used in the ascertainment of PN outcomes. Most of the studies were descriptive in nature; data were collected from STI patients or from STI service providers [30, 32, 52] from facility audits [53, 54] and/or from qualitative observation of service delivery processes [35, 36, 53], and none of the review studies was found to be methodologically stronger according to our quality ratings. Ascertainment of PN outcomes came from self-reported data from index patients and from validation of clinic records to verify partner referral or partner treatment. While a meta-analysis would be meaningless in face of such disparate studies, it is nonetheless revealing that key themes were consistent across continents, populations, and study designs, suggesting their robustness. Some of the data presented in this study was absolute number, in systematic reviews such vote counting is known to frequently bias the interpretation of findings, since this ignores the effect size and sample size of the studies. However, such counting is mainly used to categorize the study characteristics not to report any study outcomes as such.

Conclusions

Our review findings indicate that PN for STIs is feasible in developing countries and that most patients diagnosed with STIs are willing to self-notify their regular partners. Among the PN intervention strategies; counselling of index STI patients and patient delivered partner medication were found to be somewhat effective in Africa. Counselling of index STI patients is particularly useful in terms of raising awareness of PN, eliminating stigma and fear related to STIs, and should be promoted in both public and private STD clinics. Other innovative strategies should be explored and evaluated to increase PN and referral in developing countries. One example of such innovations is the use of cell phones in notifying partners, which is now widely accessible among urban and rural young adults in most developing countries [55]. Use of cell phones could be a tool to reach partners of index STI patients to inform them about possible exposure yet maintaining a good deal of confidentiality [56, 57]. The internet may be a future venue for PN as access is growing in many developing countries [58, 59]. STIs are not perceived as a major public health problem by the policy makers in most developing countries, resulting in inadequate resource allocation [10, 60–66]. Well designed PN intervention to evaluate the impact on STI prevalence and incidence outcomes with cost effectiveness data may motivate policy makers in developing countries to pay more attention formulating policies to improve quality of care in STI service facilities to promote PN.

References

Potterat JJ, Meheus A, Gallwey J: Partner notification: operational considerations. Int J STD AIDS. 1991, 2: 411-5.

Oxman AD, Scott EAF, Sellors JW, Clarke JH, Millson ME, Rasooly I, Frank JW, Naus M, Goldblatt E: Partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases: an overview of the evidence. Can J Public Health. 1994, 85: S41-7.

Low N, Broutet N, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Barton P, Hossain M, Hawkes S: Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet. 2006, 368: 2001-16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69482-8.

Cowan FM, French R, Johnson AM: The role and effectiveness of partner notification in STD control: a review. Genitourin Med. 1996, 72: 247-52.

Macke BA, Maher JE: Partner notification in the United States: an evidence-based review. Am J Prev Med. 1996, 17: 230-42. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00076-8.

Fenton KA, Peterman TA: HIV partner notification: taking a new look. AIDS. 1997, 11: 1535-46. 10.1097/00002030-199713000-00001.

World Health Organization and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: Sexually transmitted diseases: policies and principles for prevention and care. 1999, Geneva: UNAIDS Best Practice Collection

Golden MR, Anukam U, Williams DH, Hansfield HH: The legal status of patient-delivered partner therapy for sexually transmitted infections in the United States: a national survey of state medical and pharmacy boards. Sex Transm Dis. 2005, 32: 112-4. 10.1097/01.olq.0000152823.10388.99.

Arthur GR, Ngatia G, Rachier C, Mutemi R, Odhiambo J, Gilks CF: The role for government health centers in provision of same-day voluntary HIV counseling and testing in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 40: 329-35. 10.1097/01.qai.0000166376.23846.38.

Mathews C, Guttmacher SJ, Coetzee D: Evaluation of a video-based health education strategy to improve sexually transmitted disease partner notification in South Africa. Sex Transm Inf. 2002, 78: 53-7. 10.1136/sti.78.1.53.

Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, Lombard C, Guttmacher S, Oxman AD, Schmid G: Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001, CD002843-4

Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, Lombard C, Guttmacher S, Oxman A, Schmid G: A systematic review of strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2002, 13: 285-300. 10.1258/0956462021925081.

Katz BP, Danos CS, Quinn TS, Caine V, Jones RB: Efficiency and cost-effectiveness of field follow-up for patients with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in a sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 1988, 15: 11-6. 10.1097/00007435-198801000-00003.

Moyo W, Chirenje Z, Mandel J, Schwarcz SK, Klausner JD, Rutherford G, McFarland W: Impact of a single session of counseling on partner referral for sexually transmitted disease treatment, Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior. 2002, 6: 237-43. 10.1023/A:1019891808383.

Nuwaha F, Faxelid E, Neema S, Eriksson C, Höjer B: Psychosocial determinants for sexual partner referral in Uganda: qualitative results. Int J STD AIDS. 2000, 11: 156-61. 10.1258/0956462001915598.

Njeru EK, Eldridge GD, Ngugi EN, Plummer FA, Moses S: STD partner notification and referral in primary level health centers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 1995, 2: 231-5.

Nuwaha F, Faxelid E, Wabwire-Mangen F, Eriksson C, Hojer B: Psycho-social determinants for sexual partner referral in Uganda: quantitative results. Soc Sci Med. 2001, 53: 1287-1301. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00410-X.

Faxelid E, Tembo G, Ndulo J, Krantz I: Individual counseling of STD patients--a way to improve PN in the Zambian setting?. Sex Transm Dis. 1996, 23: 289-92.

Liu H, Detels R, Li X, Ma E, Yin Y: Stigma, delayed treatment, and spousal notification among male patients with sexually transmitted disease in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2002, 29: 335-43. 10.1097/00007435-200206000-00005.

World Bank: World Development Indicators database, World Bank. 2007, [http://go.worldbank.org/3JU2HA60D0]

Shekelle PG, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Woolf SH: When should clinical guidelines be updated?. BMJ. 2001, 323: 155e7-10.1136/bmj.323.7305.155.

Nuwaha F, Kambugu F, Nsubuga PS, Hojer B, Faxelid E: Efficacy of patient-delivered partner medication in the treatment of sexual partners in Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2001, 28: 105-10. 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00008.

Desormeaux J, Behets FM, Adrien M, Coicou G, Dallabetta G, Cohen M, Boulos R: Introduction of partner referral and treatment for control of sexually transmitted diseases in a poor Haitian community. Int J STD AIDS. 1996, 7: 502-6. 10.1258/0956462961918581.

Klisch SA, Mamary E, Diaz Olavarrieta C, Garcia SG: Patient-led partner notification for syphilis: Strategies used by women accessing antenatal care in urban Bolivia. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 65: 1124-35. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.025.

Gichangi P, Fonck K, Sekande-Kigondu C, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Kiragu D, Claeys P, Temmerman M: Partner notification of pregnant women infected with syphilis in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2000, 11: 257-61. 10.1258/0956462001915660.

Clark JL, Long CM, Giron JM, Cuadros JA, Caceres CF, Coates TJ, Klausner JD: Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. Partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases in Peru: knowledge, attitudes, and practices in a high-risk community. Sex Transm Dis. 2007, 34: 309-13.

Young T, de Kock A, Jones H, Altini L, Ferguson T, Wijgert van de J: A comparison of two methods of partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in South Africa: patient-delivered partner medication and patient-based partner referral. Int J STD AIDS. 2007, 18: 338-40. 10.1258/095646207780749781.

Wynendaele B, Bomba W, M'Manga W, Bhart S, Fransen L: Impact of counseling on safer sex and STD occurrence among STD patients in Malawi. Int J STD AIDS. 1995, 6: 105-9.

Faxelid E, Ahlberg BM, Maimbolwa M, Krantz I: Quality of STD care in an urban Zambian setting: the providers' perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 1997, 34: 353-7. 10.1016/S0020-7489(97)00027-8.

Green M, Hoffman I, Brathwaite A, Wedderburn M, Figueroa P, Behets F, Dallabetta G, Hoyo C, Cohen MS: Improving sexually transmitted disease management in the private sector: the Jamaica experience. AIDS. 1998, 12: S67-72. 10.1097/00002030-199815000-00009.

Harrison A, Wilkinson D, Lurie M, Connolly AM, Karim SA: Improving quality of sexually transmitted disease case management in rural South Africa. AIDS. 1998, 12: 2329-35. 10.1097/00002030-199817000-00015.

Manhart L, Dialmy A, Ryan C, Mahjour J: Sexually transmitted diseases in Morocco: gender influences on prevention and health care seeking behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 50: 1369-83. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00398-6.

Malta M, Bastos FI, Strathdee SA, Cunnigham SD, Pilotto JH, Kerrigan D: Knowledge, perceived stigma, and care-seeking experiences for sexually transmitted infections: a qualitative study from the perspective of public clinic attendees in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2007, 7: 18-10.1186/1471-2458-7-18.

Shumin C, Zhongwei L, Bing L, Rongtao Z, Benqing S, Shengji Z: Effectiveness of self-referral for male patients with urethral discharge attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2007

Mertens T, Smith G, Kantharaj K, Mugrditchian D, Radhakrishnan K: Observations of sexually transmitted disease consultations in India. Public Health. 1998, 112: 123-8.

Boonstra E, Lindbaek M, Klouman E, Ngome E, Romøren M, Sundby J: Syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases in Botswana's primary health care: quality of care aspects. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8: 604-14. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01076.x.

Steen R, Soliman C, Bucyana S, Dallabetta G: Partner referral as a component of integrated sexually transmitted disease services in two Rwandan towns. Genitourin Med. 1996, 72: 56-9.

Sahasrabuddhe VV, Gholap TA, Jethava YS, Joglekar NS, Brahme RG, Gaikwad BA, Wankhede AK, Mehendale SM: Patient-led partner referral in a district hospital based STD clinic. J Postgrad Med. 2002, 48: 105-8.

Kamali A, Quigley M, Nakiyingi J, Kinsman J, Kengeya-Kayondo J, Gopal R, Ojwiya A, Hughes P, Carpenter LM, Whitworth J: Syndromic management of sexually-transmitted infections and behaviour change interventions on transmission of HIV-1 in rural Uganda: a community randomised trial. Lancet. 2003, 361: 645-52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12598-6.

Grosskurth H, Mwijarubi E, Todd J, Rwakatare M, Orroth K, Mayaud P, Cleophas B, Buvé A, Mkanje R, Ndeki L, Gavyole A, Hayes R, Mabey D: Operational performance of an STD control programme in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2000, 76: 426-36. 10.1136/sti.76.6.426.

Hanson S, Engvall J, Sunkutu RM, Kamanga J, Mushanga M, Höjer B: Case management and patient reactions: a study of STD care in a province in Zambia. Int J STD AIDS. 1997, 8 (5): 320-8. 10.1258/0956462971920172.

Jacobs B, Whitworth J, Kambugu F, Pool R: Sexually transmitted disease management in Uganda's private-for-profit formal and informal sector and compliance with treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2004, 31: 650-4. 10.1097/01.olq.0000143087.08185.17.

Ndulo J, Faxelid E, Krantz I: Quality of care in sexually transmitted diseases in Zambia: patients' perspective. East Afr Med J. 1995, 72: 641-4.

Sano P, Sopheap S, Sun LP, Vun MC, Godwin P, O'Farrell N: An evaluation of sexually transmitted infection case management in health facilities in 4 border provinces of Cambodia. Sex Transm Dis. 2004, 31: 713-8. 10.1097/01.olq.0000145848.79694.7b.

Wang B, Li X, Stanton B, et al: Gender differences in HIV-related perceptions, sexual risk behaviors, and history of sexually transmitted diseases among Chinese migrants visiting public sexually transmitted disease clinics. AIDS Patient Care & STD. 2007, 21: 57-68.

Varghese B, Peterman TA, Holtgrave DR: Cost-effectiveness of counseling and testing and partner notification: a decision analysis. AIDS. 1999, 13: 1745-51. 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00019.

Wakasiaka SN, Bwayo JJ, Weston K, Mbithi J, Ogol C: Partner notification in the management of sexually transmitted infections in Nairobi, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2003, 80: 646-51.

Halperin DT, Epstein H: Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa's high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004, 364: 4-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3.

Dallabetta G, Gerbase AC, Holmes KK: Problems, solutions and challenges in syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Inf. 1998, 74: S1-11.

Bosu W: Syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases: is it rational or scientific?. Trop Med Internet Health. 1999, 4: 114-19. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00360.x.

Faxelid E, Ahlberg BM, Freudenthal S, Ndulo J, Krantz I: Quality of STD care in Zambia. Impact of training in STD management. Int J Qual Health Care. 1997, 9: 361-6.

Chilongozi DA, Daly CC, Franco L, Liomba NG, Dallabetta G: Sexually transmitted diseases: a survey of case management in Malawi. Int J STD AIDS. 1996, 7: 269-75. 10.1258/0956462961917951.

Lafort Y, Sawadogo Y, Delvaux T, Vuylsteke B, Laga M: Should family planning clinics provide clinical services for sexually transmitted infections? A case study from Côte d'Ivoire. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8: 552-60. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01065.x.

Harrison A, Lurie M, Wilkinson N: Exploring partner communication and patterns of sexual networking: qualitative research to improve management of sexually transmitted diseases. Health Transit Rev. 1997, 7: S103-107.

Mobile phone revolution: Developments: One world a million stories. DfID. [http://www.developments.org.uk/articles/loose-talk-saves-lives-1/]

Lim MS, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK: SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008, 19: 287-90. 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007264.

Tomnay JE, Pitts MK, Fairley CK: New technology and partner notification --why aren't we using them?. Int J STD & AIDS. 2005, 16: 19-22.

Mimiaga MJ, Fair AD, Tetu AM, Novak DS, Vanderwarker R, Bertrand T, Adelson S, Mayer KH: Acceptability of an internet-based partner notification system for sexually transmitted infection exposure among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 1009-11. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098467.

Vest JR, Valadez AM, Hanner A, Lee JH, Harris PB: Using e-mail to notify pseudonymous e-mail sexual partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2007, 34: 840-5. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318073bd5d.

Díaz-Olavarrieta C, García SG, Feldman BS, Polis AM, Revollo R, Tinajeros F, Grossman D: Maternal syphilis and intimate partner violence in Bolivia: a gender-based analysis of implications for partner notification and universal screening. Sex Transm Dis. 2007, 34: S42-6. 10.1097/01.olq.0000261725.79965.af.

Faxelid E, Ndulo J, Ahlberg BM, Krantz I: Behaviour, knowledge and reactions concerning sexually transmitted diseases: implications for partner notification in Lusaka. East Afr Med J. 1994, 71: 118-21.

Koumans EH, Barker K, Massanga M, Hawkins RV, Somse P, Parker KA, Moran J: Patient-led partner referral enhances sexually transmitted disease service delivery in two towns in the Central African Republic. Int J STD & AIDS. 1999, 10: 376-82.

Hoffman JA, Klein H: Social policy implications of partner notification for substance abusers who test HIV-positive. Res Soc Pol. 1998, 6: 17-38.

Mathews C, van Rensburg A, Coetzee N: The sensitivity of a syndromic management approach in detecting sexually transmitted diseases in patients at a public health clinic in Cape Town. S Afr Med. 1998, 88: 1337-40.

Mayaud P, Ka-Gina G, Grosskurth H: Effectiveness, impact and cost of syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases in Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 1998, 9: S11-4. 10.1258/0956462981921594.

Rao P, Mohamedali FY, Temmerman M, Fransen L: Systematic analysis of STD control: an operational model. Sex Transm Infect. 1998, 74: S17-22. 10.1136/sti.74.4.298.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/19/prepub

Acknowledgements

This review was supported in part through a grant by Australian Aid for International Development (AusAID) and by the National Institutes of Health training grant #5 D43 TW010035-07. ICDDR,B acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of AusAID and NIH to the Centre's research efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NA collected, analyzed and interpreted his data with input from SK and EC. NA, KS, EC, SHV and SK have all: (1) contributed to the design of this study, (2) participated in the writing process of this article and (3) given their accord for the publication of this article.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Alam, N., Chamot, E., Vermund, S.H. et al. Partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 10, 19 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-19