Abstract

Background

Epilepsy has long been considered to be a risk factor for psychosis. However there is a lack of consistency in findings across studies on the effect size of this risk which reflects methodological differences in studies and changing diagnostic classifications within neurology and psychiatry. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy and to estimate the risk of psychosis among individuals with epilepsy compared with controls.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted of all published literature pertaining to prevalence rates of psychosis in epilepsy using electronic databases PUBMED, OVIDMEDLINE, PsychINFO and Embase from their inception until September 2010 with the following search terms: prevalence, incidence, rate, rates, psychosis, schizophrenia, schizophreniform illness, epilepsy, seizures, temporal lobe epilepsy.

Results

The literature search and search of reference lists yielded 215 papers. Of these, 58 (27%) had data relevant to the review and 157 were excluded following a more detailed assessment. 10% of the included studies were population based studies. The pooled odds ratio for risk of psychosis among people with epilepsy compared with controls was 7.8. The pooled estimate of prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy was found to be 5.6% (95% CI: 4.8-6.4). There was a high level of heterogeneity. The prevalence of psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy was 7% (95% CI: 4.9-9.1). The prevalence of interictal psychosis in epilepsy was 5.2% (95% CI: 3.3-7.2). The prevalence of postictal psychosis in epilepsy was 2% (95% CI: 1.2-2.8).

Conclusions

Our systematic review found that up to 6% of individuals with epilepsy have a co-morbid psychotic illness and that patients have an almost eight fold increased risk of psychosis. The prevalence rate of psychosis is higher in temporal lobe epilepsy (7%). We suggest that further investigation of this association could give clues to the aetiology of psychosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The nature of the relationship between psychosis and epilepsy has been of great interest to psychiatrists for over a century [1–12]. In one of the most epidemiologically complete studies involving direct patient interviews of all individuals with epilepsy in Iceland, Gudmundson (1966) reported a rate of psychosis of 7.2% [13]. In keeping with this the majority of studies [3, 4, 14, 15] have found a higher prevalence of psychosis in patients with epilepsy compared with the general population, but this finding is not consistent and reported rates varying from 0.48% [16] to 35.7% [17]. Methodological differences such as changing diagnostic classifications, clinical heterogeneity, different ascertainment methods, and lack of power likely account for much of the inconsistency. Previous qualitative reviews of this topic these reported an overall rate of psychosis in epilepsy of 7% and 7.6% respectively [18, 19]. More recently Gaitatziz et al. looking at psychiatric morbidity overall in epilepsy more recently, estimated that the prevalence of psychosis in population based studies at between 2-7% and estimated a prevalence of psychosis at 10-19% in patients with TLE or refractory epilepsy [12].

Improving our understanding of the basis to the relationship between psychosis and epilepsy is important as it may provide clues to the pathophysiology of psychosis generally [4, 20, 21]. In the current investigation we have undertaken the first systematic review of the prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy. Our main aim was to estimate the overall pooled prevalence of psychosis among patients with epilepsy. Secondary aims were 1) to examine the prevalence of psychosis associated specifically with temporal lobe epilepsy, 2) to estimate the prevalence of postictal and interictal psychosis, 3) to estimate prevalence of psychosis in specific subgroups of patients with intellectual disability, children and adolescents, and individuals with genetic vulnerability to psychosis and 4) to carry out separate analysis for studies with control groups to allow estimation of risk for psychosis among patients with epilepsy in terms of pooled odds ratios.

Methods

Study selection

We conducted a systematic review of all published literature in English on the prevalence of psychosis in patients with epilepsy. We were guided by PRISMA criteria[22]. A search was undertaken of the electronic databases PUBMED, OVID MEDLINE and EMBASE from their inception to September 2010 with the following terms: prevalence, incidence, rate, rates, psychosis, schizophrenia, schizophreniform illness, epilepsy, seizures and temporal lobe epilepsy. In addition to this search procedure, we used the reference lists of the identified publications to find further relevant articles.

Inclusion criteria

Papers were included if they gave prevalence rates of psychosis, schizophrenia, interictal psychosis (see definition below) or postictal psychosis (see definition below) in persons with epilepsy. We included studies involving adults, children and patients with learning disability.

The definition of interictal psychosis (also known as the schizophrenia-like psychosis in epilepsy) is a psychotic disorder that would fulfill diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia if epilepsy was not present. The interictal psychotic disorders are of reasonably long duration and are not related to the occurrence of seizures [4, 23].

The definition of postictal psychosis is a psychosis that manifests itself immediately upon a seizure or emerges with one week of return of apparently normal mental function .The psychosis has to last a minimum length of 24 hours and a maximum length of 3 months [23].

Exclusion criteria

Papers excluded were those that (a) did not have the full article published in English, (b) did not report prevalence rates or data from which rates could be calculated (c) involved case reports, letters, short reports, reviews or book chapters.

Data extraction

Following initial searches, all titles of papers and abstracts were examined and assessed for relevance and appropriateness of the main question under review. Full texts of potentially relevant papers were obtained. Authors of papers were contacted where necessary. The methodological quality of studies was assessed.

For the purpose of the meta-analysis, we extracted the following domains or variables from the articles that were finally included:

-

1)

prevalence rates for psychosis including interictal and postictal psychosis and schizophrenia. (where specified)

-

2)

date of publication, country (developing or developed world), year of publication, proportion of children or individuals with learning disability within epilepsy sample.

-

3)

sample size, gender composition, whether the study was carried out in a hospital or community setting, study design (cross-sectional or cohort),

-

4)

diagnosis of epilepsy and whether International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification was used

-

5)

diagnostic tools used for psychosis and method of obtaining diagnosis- (unstructured interview, case note review, structured interview).

Data analysis

Pooled estimates of the prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy patients were calculated using random-effects meta-analysis. This allows a more robust and true estimate of effect size and one that is weighted by the sample size of individual studies. A random effects model weights studies more equally and is considered more appropriate for meta-analyses with substantial heterogeneity [24, 25] and this meta-analytic approach has been used with data containing similar levels to those seen here [25]. The between-study variance or heterogeneity in estimates was modelled using Cochran Q and the I2 statistic. The Q statistic is reported with χ2 and p-values and the I2 statistic is reported as a percentage with increasing values indicating greater heterogeneity between estimates of individual studies (I2 <25% indicates low heterogeneity; 30-70% = moderate heterogeneity and >75% indicates high heterogeneity [25]. Meta-regression was used to estimate the extent to which measured covariates (study design, study setting, assessment instrument used, types of epilepsy, year of study, family history of psychiatric illness, International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification used, exclusion criteria applied, country in which study took place) could explain the observed heterogeneity in prevalence estimates across studies. The regression coefficients (β) reported indicate the average difference in prevalence proportion for one category compared to the other (eg assessment by clinical interview versus case notes). Effects of individual covariates were examined first in univariate models and then in a multivariate model constructed in a step-wise fashion. All analyses were carried out using STATA statistical software package, version 11.0.

Results

Literature search

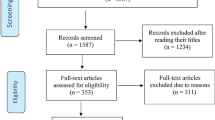

Our preliminary search identified a total of 431 papers on EMBASE, 773 papers on PUBMED and 999 papers on MEDLINE via OVID. There was a substantial degree of overlap between the 3 databases.

After these titles were screened, 215 papers were examined in detail. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 58 papers (27%) were deemed to have data relevant to the systematic review and meta-analysis. See Figure 1.

Included studies and study design

Thirteen of the studies were from the UK, 11 from the US, 11 from Japan, 5 from Brazil, 2 from Denmark, 2 from the Netherlands, 2 from Canada, 2 from India,2 from Iceland, 2 from Australia and 6 from other countries.

Ten papers specified the gender of participants in the study. The number of patients with psychosis in the studies varied from 1 [16, 26–28] to 795 [29].

The number of participants in studies varied from 50 [30] to 34,494 [29]. With regard to the prevalence rates, forty-eight studies were cross sectional studies, 9 were cohort and 1 was case control. The time periods over which the prevalence rates were calculated were as follows: 27 studies were for an unknown time period, 7 studies were lifetime prevalence studies, 21 studies were for more than 1 year and 3 studies were less than 1 year. Only 6 of the studies had control groups [31–36].

Seven studies were in a community setting, 3 were in a mixed hospital/community setting, 1 was unknown, 3 were from population databases and the remaining 44 were from hospital settings.

In 39 of the studies, patients were interviewed, in 19 studies the patients were not interviewed or it was not stated in the study.

The prevalence rates of psychosis varied from 0.02% [37] to 27% [17]. Forty of the studies used ICD criteria or DSM criteria for diagnosis. Of these studies, 17 used DSM IV criteria, 5 used DSM IIIR criteria, 1 used DSM III criteria, 1 used DSM II criteria, 6 used ICD 10 criteria, 4 used ICD 9 criteria and 1 used ICD 8 criteria. 5 studies used a mixture of these criteria.

Seven studies used a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV on patients in their studies [26, 31, 38–42]. Nine studies were conducted before 1990.

Seventeen of the 58 studies gave the prevalence of schizophrenia. Ten studies had prevalence rates for interictal psychosis. Thirteen studies had prevalence rates for postictal psychosis. Three studies used a sample group of patients with children/adolescents only [14, 27, 43]. Four studies studied patients with Learning Disability only [32, 44–46]. Seventeen studies included patients with TLE only. Seven of the studies mentioned a family psychiatric history, only 3 mentioned a family history of psychosis. 17 studies had TLE patients only, in 26 studies, the authors did not differentiate whether patients had TLE or not and in 15 studies, there was a mixture of patients with TLE and other forms of epilepsy but unfortunately it was not possible to extract the non TLE or TLE sample from each other. Therefore for the TLE prevalence sample, we only used studies where all the patients had TLE. We did not contact authors personally to access data as this was not possible in many of the studies as the contact details were not current and 22 of the studies were conducted before 2000.

Prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy

Overall, the pooled prevalence rate for psychosis in epilepsy patients was 5.6% (95% CI =4.8-6.4). (see Figure 2). The pooled prevalence rate when postictal psychosis was excluded was 5.4% (95% CI = 4.5-6.2).

The pooled prevalence rate for psychosis in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy was 7.0% (CI 4.9-9.1). (See Figure 3). The pooled prevalence rate of interictal psychosis was 5.2% (95% CI 3.2-7.2) and the pooled prevalence rate for post ictal psychosis was 2.0% (95% CI 1.2-2.8).

Four papers studied an intellectual disability sample only [32, 44–46]. The prevalence of psychosis in patients with epilepsy and comorbid learning disability was 7.4% (95% CI 2.6-12.2).

Three studies used child and adolescent subjects only [14, 27, 43]. The prevalence of psychosis in children and adolescents with epilepsy was 5.4%, (95% CI 0.6-10.2).

Three papers mentioned a family history of psychosis. The prevalence of psychosis in patients with epilepsy where a family history of psychosis was present was 5.4% (95% CI = 1-9.8).

Six of the studies had control groups. However, only 4 studies [31, 34–36] were used for analysis because two of them [32, 33] had no psychosis outcome in the control group so an odds ratio could not be calculated. The pooled odds ratio for risk of psychosis among people with epilepsy was 7.83. (See Figure 4).

Heterogeneity analyses

There was substantial heterogeneity between the prevalence estimates of psychosis in epilepsy patients across individual studies (I2 > 70%). We examined the effect of nine factors on the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy patients found across studies in a meta-regression analysis: (1) study design (2) study setting (3) instrument used to assess psychotic symptoms (4) types of epilepsy (5) year of study (6) family history of psychosis noted (7) ILAE classification used (8) exclusion criteria applied (9) country in which the study took place.

Meta-regression analyses

None of the following factors significantly explained any of the variance in the estimates on an individual basis. (1) Study Design: (β = -1.1,SE(β = 1.9, p =0.58). (2) Study setting: (whether recruiting patients from the community or from hospitals or from tertiary centres) = (β -0.11, SE = (β) = 0.9, p =0.90). (3) Instrument used to assess psychosis: (employing a clinical interview or using case notes) (β = 0.31, SE(β) = 1.7, p =0.85). 4) Types of epilepsy reported: (all types of epilepsy patients or temporal lobe epilepsy patients only or other types of epilepsy) = (β = 0.74, SE(β) = 0.8, p =0.39). 5) Year of study: (whether studies carried out before 1990 or after 1990) (β = -2.8, SE (β) = 2.1, p =0.17). 6) Family history of psychosis: family of history of psychosis assessed or not assessed = (β = 3.7, SE(β) = 2.1, p =0.09).

7) ILAE classification used: studies reporting use of ILAE classification or not reporting this classification = (β = 0.3 , SE (β) = 1.7, p =0.85). 8) Exclusion criteria applied: studies reporting the use of exclusion criteria or those not reporting exclusion criteria (β = 1.1, SE(β) = 1.4, p =0.45). 9) Country in which study took place: studies from countries classified as ‘developed’ or those classified as ‘not developed’ (β = 2.0, SE(β) = 1.9, p =0.31).

A multivariate model constructed in step-wise fashion showed that the specific combination of 5 factors explained the largest amount of heterogeneity in the prevalence estimates: Study setting; Assessment instrument used; Year of study, Family history of psychosis; Type of epilepsy. These 5 variables together explained 10% of the variance in estimates of the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy patients across studies.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the prevalence rate of psychosis in epilepsy. Our finding of 5.6% pooled prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy is lower than estimates of approximately 7% estimates from previous narrative reviews, [18, 19] although our finding of 7% for the rate of psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy is similar. Based on results from population based studies with control samples, [31, 34–36] we found that the rate of psychosis among people with epilepsy is 7.8 times higher than in people without epilepsy. However there were very few studies fulfilling these criteria. Our findings are consistent with Gudmundsson who found that 7.2% of subjects with epilepsy were currently or had at some time suffered from psychotic illness [13].

We found a low prevalence of postictal psychosis in epilepsy-2%. This has traditionally been described as the most common form of psychosis in patients with epilepsy [23]. Prevalence rates of around 6% from two telemetry series have been reported in the past [39, 47]. The relatively low postictal rate found in this study may be explained by the transitory nature of PIP, it’s acute and short presentation and that it is often managed in non specialised departments and may go undiagnosed. It may be mistaken for acute confusional states rather than postictal psychosis. However, postictal psychosis may be over or under represented depending on the availability of psychiatric assessment, the frequency of review and potentially the knowledge base of the treating neurologist and neuropsychiatry teams. The rate of interictal psychosis at 5.2% was over two and a half times the rate of postictal psychosis, but similar to the rate for overall psychosis in epilepsy.

TLE is the most common of the anatomically defined syndromes accounting for around 60% of all patients with localisation related epilepsies [23]. It is the most common type of epilepsy in adults who experience seizures poorly controlled by anticonvulsant medication. Our results found a slighter higher rate of psychosis in TLE as compared to all epilepsies (7% v 5.6%). There has been some debate in the past whether there is a higher rate of schizophrenia-like-psychosis in patients with TLE compared to generalized epilepsies. In the original study by Slater et al., the high rates of psychosis may have been in part due to somewhat imprecise clinical diagnostic data as the terms schizophrenia and psychosis were relatively loosely defined by today’s standards [4]. There is also the possibility of an ascertainment bias as the study drew its subjects from tertiary centres in two major London hospitals. More recently, Stevens argued that the proportion of TLE in epilepsy-psychosis patients is similar to the proportion rate of generalized epilepsy patients with epilepsy psychosis which is estimated to be about 60% [48–50]. Furthermore, in the large epidemiological study by Qin et al., patients with localization related epilepsy were only slightly over-represented among those who were psychotic and this difference fell short of statistical significance [29]. Several studies have failed to confirm the commonly held view that there is a specific association between temporal lobe epilepsy and psychopathology which is in contrast to commonly accepted clinical practice [51–53].

Methodological issues

Most of the studies included in this review were cross sectional in design (77.6%) and based on samples from tertiary referral centres (71%) and these factors may limit the interpretation of the results with respect to the general population. Only 10% of the studies were population-based. Prevalence measures derived from such unrepresentative samples may therefore overestimate psychiatric morbidity among epilepsy patients [54].

We were unable to draw conclusions about the influence of a genetic vulnerability to psychosis from this study as data was too limited. Family history of psychosis was only mentioned in 3 studies [29, 34, 39]. Further family studies are needed to elucidate this association. Heterogeneity may also play a role.

It was not possible to identify a group of patients which did not have temporal lobe epilepsy to compare with the TLE group as some studies did not state whether the patients had TLE or not and also some studies has TLE and non TLE patients mixed together in their study samples, thus it was impossible to differentiate these 2 disparate groups out.

Temporality of the association between epilepsy and psychosis

The question of whether epilepsy is a risk factor for psychosis and/or whether psychosis is a risk factor for epilepsy has repeatedly arisen in the literature, however, very few studies had the data necessary to adequately provide answers [55]. We have not addressed the temporality of the association in this study because the majority of studies included do not have temporal information. However, Clarke et al. have recently found in a population based family study that patients with epilepsy have a 5.5 fold increase in the risk of having a broadly defined psychotic disorder and an 8.5 fold increase in the risk of having schizophrenia [56]. Individuals with a parental history of epilepsy had a 2 fold increase in the risk of developing psychosis, compared to individuals without a parental history of epilepsy. Individuals with a parental history of psychosis had reciprocally a 2.7 fold increase in the risk of having a diagnosis of generalised epilepsy compared to individuals without a parental history of psychosis. Post hoc analyses showed that these analyses were not driven by the comorbidity of epilepsy and psychosis in the parents.

Classification of psychosis

A consensus on the classification of psychotic symptoms associated with epilepsy is lacking [57]. Neither ICD 10 nor DSM V classify seizure-related psychosis separately. It could be debated whether postictal psychosis for example should be classified as a brief psychotic disorder/psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition or a psychotic disorder not otherwise specified in DSM. Furthermore, the psychopathology of patients with epilepsy can be atypical and does not readily conform to these diagnostic manuals [58]. A dedicated sub-commission of the International League Against Epilepsy commission on neuropsychiatric aspects has developed a proposal on the classification of neuropsychiatric disorders in epilepsy [59]. Recent genetic studies reinforce the view that more attention should be given to the relationship between the functional psychoses and neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism [60].

Possible mechanisms

It has been suggested that the neurotoxic effect of epilepsy explains the association between epilepsy and psychosis [55]. Various mechanisms through which this effect might be brought about have been proposed. These include firstly, a ‘kindling’ process whereby acute seizure discharges may cause changes in brain function perhaps through receptor-based changes and changes in cerebral blood flow [61]; secondly, a ‘forced normalisation’ process whereby an inverse relationship exists between seizure control and psychotic symptoms [57, 62] and thirdly, on-going subictal activity in the limbic system that is undetectable on EEG but which leads to brain changes that result in psychosis [55, 63].

Antiepileptic medication may also play a role in the development of psychosis especially among patients with other risk factors such as family history or past psychiatric history. Psychoses have been noted as a potential adverse effect in many different antiepileptic medications suggesting that the phenomenon is not medication specific. Antiepileptic medications implicated include ethosuxamide, topiramate, vigabatrin, zonisamide and leviteracetam [64]. One study found a prevalence of psychosis of 3.7% in patients after they were commenced on topiramate [65]. High starting doses of medication and a rapid titration schedule in more vulnerable patients with past psychiatric history and with more severe epilepsy with high seizure frequency were associated with greater risk.

However, it is also possible that epilepsy and psychotic illness may represent different outcomes of a common aetiological process. Neuropathological, neuroimaging and genetics findings show that similar structural brain abnormalities and genetic abnormalities are present in patients with schizophrenia and patients with epilepsy [55, 66–71]. For instance, enlarged ventricles have been found to be common to first episode psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy patients without psychosis [67]. Neuronal migration defects have been proposed as a mechanism related to enlarged ventricles and this defect could be common both to schizophrenia and epilepsy. From a neurobiological perspective, significant grey and white matter deficits occur in temporal lobe epilepsy with psychosis. Some of these deficits overlap with those found in schizophrenia. These include the medial temporal structures but also extend to lateral temporal and extratemporal regions [70].

Recent genetic work shows that a rare genetic mutation can lead to either epilepsy or schizophrenia. A micro-deletion in the genomic area 15q 13–14 containing the nicotine receptor was linked to development of either schizophrenia or juvenile epilepsy [68, 69, 71]. The gene leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 gene (LGI1) in autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features, [72, 73] may also play a role in regulating glutaminergic synaptic transmission, a process that is involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia [74]. Genes encoding ion channels may also be a source of interest. Ion channelopathies are known to underlie some epilepsies and it has been shown that variation within the gene CACNA1C (encoding a subunit of the L-type voltage dependent calcium channel) is associated with schizophrenia as well as depression and bipolar affective disorder [75]. This study provides support for the possibility that some people might experience both psychosis and epilepsy at least in part because of an underlying vulnerability to both.

Conclusions

In summary, adequate recognition and treatment of psychosis in epilepsy is essential for patient management because of their considerable burden in morbidity and quality of life [12, 76]. We would recommend that future studies in this area should be used for defining psychotic presentations. Improved diagnostic classification would allow better characterisation of prevalence rates. Unfortunately standardized criteria for psychiatric disorders such as ICD 10 or DSM V do not allow this presently. Further investigations in population-based studies are warranted for a more accurate prevalence rate at a population level and family-based studies are needed to investigate the possible clustering of psychosis and epilepsy within families. In conclusion, this study is the first meta-analysis and systematic review on the prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy. The methodological rigour of a systematic review adds clarity to the previous findings on this topic and confirms the results. We report an almost 8-fold increased risk of psychosis in epilepsy. An improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying this association would be a fruitful line of enquiry and may yield useful information on the aetiopathogenesis of both psychosis and epilepsy.

Authors´ information

Mary Cannon and David Cotter are joint senior author contributors.

References

Esquirol E: Des Maladies Mentales Considerees sous les Rapports Medical. J.B Balliere. 1838

Kraeplin E: Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und Artze. 1913, Leipzig: Barth

Gibbs EL, Gibbs FA, Fuster B: Psychomotor epilepsy. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1948, 60 (4): 331-339. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1948.02310040002001.

Slater E, Beard AW, Glithero E: The schizophrenialike psychoses of epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry. 1963, 109: 95-150. 10.1192/bjp.109.458.95.

Flor-Henry P: Psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy. A controlled investigation. Epilepsia. 1969, 10 (3): 363-395. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1969.tb03853.x.

Scott DF: Psychiatric aspects of epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry. 1978, 132: 417-430. 10.1192/bjp.132.5.417.

Trimble MR: The Psychoses of Epilepsy. 1991, New York: Raven Press

Kanner AM, Barry JJ: Is the psychopathology of epilepsy different from that of nonepileptic patients?. Epilepsy & behavior: E&B. 2001, 2 (3): 170-186. 10.1006/ebeh.2001.0192.

Krishnamoorthy ES: Psychiatric issues in epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001, 14 (2): 217-224. 10.1097/00019052-200104000-00014.

Marsh L, Rao V: Psychiatric complications in patients with epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Res. 2002, 49 (1): 11-33. 10.1016/S0920-1211(02)00008-6.

Devinsky O: Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with epilepsy: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Epilepsy Behav. 2003, 4 (Suppl 4): S2-10.

Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW: The psychiatric comorbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004, 110 (4): 207-220. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00324.x.

Gudmundsson G: Epilepsy in Iceland. A clinical and epidemiological investigation. Acta Neurol Scand. 1966, 43 (Suppl 25): 21-124.

Lindsay J, Ounsted C, Richards P: Long-term outcome in children with temporal lobe seizures. III: psychiatric aspects in childhood and adult life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1979, 21 (5): 630-636.

Schmitz BWP: Psychosis in epilepsy: frequency and risk factors. Journal of Epilepsy. 1995, 8 (4): 295-305. 10.1016/0896-6974(95)00051-8.

Swinkels WA, Kuyk J, Van Dyck R, Spinhoven P: Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005, 7 (1): 37-50. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.04.012.

Jensen I, Larsen JK: Mental aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy. Follow-up of 74 patients after resection of a temporal lobe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1979, 42 (3): 256-265. 10.1136/jnnp.42.3.256.

McKenna PJ, Kane JM, Parrish K: Psychotic syndromes in epilepsy. Am J Psychiatry. 1985, 142 (8): 895-904.

Trimble MR: Behaviour changes following temporal lobectomy, with special reference to psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992, 55 (2): 89-91. 10.1136/jnnp.55.2.89.

Toone BK: The psychoses of epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000, 69 (1): 1-3. 10.1136/jnnp.69.1.1.

Adachi N, Akanuma N, Ito M, Kato M, Hara T, Oana Y, Matsuura M, Okubo Y, Onuma T: Epileptic, organic and genetic vulnerabilities for timing of the development of interictal psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 196 (3): 212-216. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056721.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 151 (4): 264-269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W264

David AS, Fleminger S, Kopelman MD, Lovestone S, Mellers JDC: Lishman's Organic Psychiatry. 2010, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, Fourth

Egger MS, Altman GD, George D: Systematic reviews in healthcare: meta-analysis in context. 2001, Oxford: BMJ Books, 2

Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Goodwin GM, Langstrom N: Bipolar disorder and violent crime: new evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010, 67 (9): 931-938. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.97.

Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Kanner AM, Meador KJ: Clinical assessment of Axis I psychiatric morbidity in chronic epilepsy: a multicenter investigation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005, 17 (2): 172-179. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.2.172.

McLellan A, Davies S, Heyman I, Harding B, Harkness W, Taylor D, Neville BG, Cross JH: Psychopathology in children with epilepsy before and after temporal lobe resection. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005, 47 (10): 666-672. 10.1017/S0012162205001362.

Siegel AM, Cascino GD, Fessler AJ, So EL, Meyer FB: Psychiatric co-morbidity in 75 patients undergoing epilepsy surgery: lack of correlation with pathological findings. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 80 (2–3): 158-162.

Qin P, Xu H, Laursen TM, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB: Risk for schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like psychosis among patients with epilepsy: population based cohort study. Bmj. 2005, 331 (7507): 23-10.1136/bmj.38488.462037.8F.

Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, Hermann B: Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998, 39 (5): 478-486. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x.

De Araujo Filho GM, Pascalicchio TF, Sousa Pda S, Lin K, Ferreira Guilhoto LM, Yacubian EM: Psychiatric disorders in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a controlled study of 100 patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2007, 10 (3): 437-441. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.01.016.

Deb S, Hunter D: Psychopathology of people with mental handicap and epilepsy. I: maladaptive behaviour. Br J Psychiatry. 1991, 159 (822–826): 833-824.

Jalava M, Sillanpaa M: Concurrent illnesses in adults with childhood-onset epilepsy: a population-based 35-year follow-up study. Epilepsia. 1996, 37 (12): 1155-1163. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00547.x.

Mendez MF, Grau R, Doss RC, Taylor JL: Schizophrenia in epilepsy: seizure and psychosis variables. Neurology. 1993, 43 (6): 1073-1077. 10.1212/WNL.43.6.1073.

Stefansson SB, Olafsson E, Hauser WA: Psychiatric morbidity in epilepsy: a case controlled study of adults receiving disability benefits. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998, 64 (2): 238-241. 10.1136/jnnp.64.2.238.

van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Aldenkamp AP, Ader HJ, Boenink A, Linszen D, Van Dyck R: Psychosis in epilepsy patients and other chronic medically ill patients and the role of cerebral pathology in the onset of psychosis: a clinical epidemiological study. Seizure. 2008, 17 (5): 446-456. 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.12.004.

Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, Davidian H, Mohammadi M, Norouzian M: Prevalence of epilepsy and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in Iran. Seizure. 2006, 15 (7): 476-482. 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.05.011.

Victoroff J: DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in candidates for epilepsy surgery: lifetime prevalence. Neuropsychiatry, neuropsychology and behavoural neurology. 1994, 7 (2): 87-97.

Alper K, Devinsky O, Westbrook L, Luciano D, Pacia S, Perrine K, Vazquez B: Premorbid psychiatric risk factors for postictal psychosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001, 13 (4): 492-499. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13.4.492.

Kanner AM, Byrne R, Chicharro A, Wuu J, Frey M: A lifetime psychiatric history predicts a worse seizure outcome following temporal lobectomy. Neurology. 2009, 72 (9): 793-799. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343850.85763.9c.

Filho GM, Rosa VP, Lin K, Caboclo LO, Sakamoto AC, Yacubian EM: Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a study comparing patients with mesial temporal sclerosis and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008, 13 (1): 196-201. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.01.008.

Sanchez-Gistau V, Pintor L, Sugranyes G, Bailles E, Carreno M, Donaire A, Boget T, Setoain X, Bargallo N, Rumia J: Prevalence of interictal psychiatric disorders in patients with refractory temporal and extratemporal lobe epilepsy in Spain. A comparative study. Epilepsia. 2010, 51 (7): 1309-1313.

Caplan R, Arbelle S, Magharious W, Guthrie D, Komo S, Shields WD, Chayasirisobhon S, Hansen R: Psychopathology in pediatric complex partial and primary generalized epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998, 40 (12): 805-811.

Espie CA, Watkins J, Duncan R, Sterrick M, McDonach E, Espie E, McGarvey C: Perspectives on epilepsy in people with intellectual disabilities: comparison of family carer, staff carer and clinician score profiles on the Glasgow Epilepsy Outcome Scale (GEOS). Seizure. 2003, 12 (4): 195-202. 10.1016/S1059-1311(02)00265-0.

Ring H, Zia A, Lindeman S, Himlok K: Interactions between seizure frequency, psychopathology, and severity of intellectual disability in a population with epilepsy and a learning disability. Epilepsy Behav. 2007, 11 (1): 92-97. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.04.002.

Pawar DG: Comparative survey of comorbidities in people with learning disability with or without epilepsy. The Psychiatrist. 2008, 32: 224-226.

Kanner AM, Stagno S, Kotagal P, Morris HH: Postictal psychiatric events during prolonged video-electroencephalographic monitoring studies. Arch Neurol. 1996, 53 (3): 258-263. 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550030070024.

Stevens JR: Psychosis and the temporal lobe. Neurobehavioral problems in epilepsy. 1991, New York: Raven Press, 55: 79-96.

Shorvon SD: Epidemiology, classification, natural history, and genetics of epilepsy. Lancet. 1990, 336 (8707): 93-96. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91603-8.

Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Rocca WA: Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clinic proceedings Mayo Clinic. 1996, 71 (6): 576-586. 10.4065/71.6.576.

Stevens JR: Psychiatric aspects of epilepsy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988, 49 (Suppl): 49-57.

Manchanda R, Schaefer B, McLachlan RS, Blume WT: Interictal psychiatric morbidity and focus of epilepsy in treatment-refractory patients admitted to an epilepsy unit. Am J Psychiatry. 1992, 149 (8): 1096-1098.

Swinkels WA, Kuyk J, De Graaf EH, Van Dyck R, Spinhoven P: Prevalence of psychopathology in Dutch epilepsy inpatients: a comparative study. Epilepsy Behav. 2001, 2 (5): 441-447. 10.1006/ebeh.2001.0242.

Edeh J, Toone B: Relationship between interictal psychopathology and the type of epilepsy. Results of a survey in general practice. Br J Psychiatry. 1987, 151: 95-101. 10.1192/bjp.151.1.95.

Cascella NG, Schretlen DJ, Sawa A: Schizophrenia and epilepsy: is there a shared susceptibility?. Neurosci Res. 2009, 63 (4): 227-235. 10.1016/j.neures.2009.01.002.

Clarke MC, Tanskanen A, Huttunen MO, Clancy M, Cotter DR, Cannon M: Evidence for shared susceptibility to epilepsy and psychosis: a population-based family study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012, 71 (9): 836-839. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.011.

Sachdev P: Schizophrenia-like psychosis and epilepsy: the status of the association. Am J Psychiatry. 1998, 155 (3): 325-336.

Anhoury S, Brown RJ, Krishnamoorthy ES, Trimble MR: Psychiatric outcome after temporal lobectomy: a predictive study. Epilepsia. 2000, 41 (12): 1608-1615.

Krishnamoorthy ES, Trimble MR, Blumer D: The classification of neuropsychiatric disorders in epilepsy: a proposal by the ILAE Commission on Psychobiology of Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007, 10 (3): 349-353. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.10.002.

Craddock N, Owen MJ: The Kraepelinian dichotomy - going, going… but still not gone. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 196 (2): 92-95. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.073429.

Lax Pericall MT, Taylor E: Psychosis and epilepsy in young people. Epilepsy Behav. 2010, 18 (4): 450-454. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.05.017.

Jones NC, Martin S, Megatia I, Hakami T, Salzberg MR, Pinault D, Morris MJ, O'Brien TJ, van den Buuse M: A genetic epilepsy rat model displays endophenotypes of psychosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2010, 39 (1): 116-125. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.02.001.

Elliott B, Joyce E, Shorvon S: Delusions, illusions and hallucinations in epilepsy: 2. Complex phenomena and psychosis. Epilepsy Res. 2009, 85 (2–3): 172-186.

Mula M, Monaco F: Antiepileptic drugs and psychopathology of epilepsy: an update. Epileptic Disord. 2009, 11 (1): 1-9.

Mula M, Trimble MR, Lhatoo SD, Sander JW: Topiramate and psychiatric adverse events in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003, 44 (5): 659-663. 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.05402.x.

Bruton CJ, Stevens JR, Frith CD: Epilepsy, psychosis, and schizophrenia: clinical and neuropathologic correlations. Neurology. 1994, 44 (1): 34-42. 10.1212/WNL.44.1.34.

Barr WB, Ashtari M, Bilder RM, Degreef G, Lieberman JA: Brain morphometric comparison of first-episode schizophrenia and temporal lobe epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry. 1997, 170: 515-519. 10.1192/bjp.170.6.515.

Helbig I, Mefford HC, Sharp AJ, Guipponi M, Fichera M, Franke A, Muhle H, De Kovel C, Baker C, Von Spiczak S, Kron KL, Steinich I, Kleefuss-Lie AA, Leu C, Gaus V, Schmitz B, Klein KM, Reif PS, Rosenow F, Weber Y, Lerche H, Zimprich F, Urak L, Fuchs K, Feucht M, Genton P, Thomas P, Visscher F, de Haan GJ, Møller RS, et al: 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nature genetics. 2009, 41 (2): 160-162. 10.1038/ng.292.

Masurel-Paulet A, Andrieux J, Callier P, Cuisset JM, Le Caignec C, Holder M, Thauvin-Robinet C, Doray B, Flori E, Alex-Cordier MP, Beri M, Boute O, Delobel B, Dieux A, Vallee L, Jaillard S, Odent S, Isidor B, Beneteau C, Vigneron J, Bilan F, Gilbert-Dussardier B, Dubourg C, Labalme A, Bidon C, Gautier A, Pernes P, Pinoit JM, Huet F, Mugneret F, et al: Delineation of 15q13.3 microdeletions. Clinical genetics. 2010, 78 (2): 149-161. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01374.x.

Sundram F, Cannon M, Doherty CP, Barker GJ, Fitzsimons M, Delanty N, Cotter D: Neuroanatomical correlates of psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy: voxel-based morphometry study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 197 (6): 482-492. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080218.

Vassos E, Collier DA, Holden S, Patch C, Rujescu D, St Clair D, Lewis CM: Penetrance for copy number variants associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2010, 19 (17): 3477-3481. 10.1093/hmg/ddq259.

Kalachikov S, Evgrafov O, Ross B, Winawer M, Barker-Cummings C, Martinelli Boneschi F, Choi C, Morozov P, Das K, Teplitskaya E, Yu A, Cayanis E, Penchaszadeh G, Kottmann AH, Pedley TA, Hauser WA, Ottman R, Gilliam TC, et al: Mutations in LGI1 cause autosomal-dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features. Nat Genet. 2002, 30 (3): 335-341. 10.1038/ng832.

Morante-Redolat JM, Gorostidi-Pagola A, Piquer-Sirerol S, Saenz A, Poza JJ, Galan J, Gesk S, Sarafidou T, Mautner VF, Binelli S, Staub E, Hinzmann B, French L, Prud'homme JF, Passarelli D, Scannapieco P, Tassinari CA, Avanzini G, Martí-Massó JF, Kluwe L, Deloukas P, Moschonas NK, Michelucci R, Siebert R, Nobile C, Pérez-Tur J, López de Munain A: Mutations in the LGI1/Epitempin gene on 10q24 cause autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002, 11 (9): 1119-1128. 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1119.

Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Iwanaga T, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA, Fukata M: Epilepsy-related ligand/receptor complex LGI1 and ADAM22 regulate synaptic transmission. Science. 2006, 313 (5794): 1792-1795. 10.1126/science.1129947.

Ferreira MA, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, Fan J, Kirov G, Perlis RH, Green EK, Smoller JW, Grozeva D, Stone J, Nikolov I, Chambert K, Hamshere ML, Nimgaonkar VL, Moskvina V, Thase ME, Caesar S, Sachs GS, Franklin J, Gordon-Smith K, Ardlie KG, Gabriel SB, Fraser C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Breen G, Gill M, et al: Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (9): 1056-1058. 10.1038/ng.209.

De Boer HM, Mula M, Sander JW: The global burden and stigma of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008, 12 (4): 540-546. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.12.019.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/75/prepub

Acknowledgements

Mary Cannon was supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the Health Research Board Ireland and an Essel NARSAD Independent Investigator Award. Mary Clarke and Mary Cannon have received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2010-241909 (Project EU-GEI). EU-GEI is the acronym of the project “European network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions”. David Cotter was supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the Health Research Board Ireland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MJC and DRC conceived the idea for the study. MJC and DJC were responsible for the data collection. MCC was responsible for all the statistical analysis. MJC wrote the first draft of the paper. MJC, MCC, MC and DRC all reviewed and edited the manuscript. MJC, MCC, MC and DRC revised it critically. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Maurice J Clancy, Mary C Clarke contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Clancy, M.J., Clarke, M.C., Connor, D.J. et al. The prevalence of psychosis in epilepsy; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 14, 75 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-75

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-75