Abstract

Background

Integrated Treatment (IT) has proved effective in treating patients with Substance Use Disorders (SUD) co-occurring with severe Mental Disorders (MD), less is known about the effectiveness of IT for patients with SUD co-occurring with less severe MD.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of IT for patients with SUD co-occurring with anxiety and/or depression on the following parameters:

1. The use of substances, as measured by the Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT), the Drug Use Identification Test (DUDIT), and the Addiction Severity Index (EuropASI).

2. The severity of psychiatric symptoms, as measured by the Symptom Check List 90 r (SCL 90R).

3. The client’s motivation for changing his/her substance use behaviour, as measured by the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATSr).

Methods

This is a group randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of IT to treatment as usual in Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs). Five CMHCs were drawn to the Intervention Group (IG) and four CMHCs to the Control Group (CG). The allocation to treatment conditions was not blinded. New referrals were screened with the AUDIT and the DUDIT. Those who scored above the cut-off level of these instruments were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV 1 and 2. We included patients with anxiety and/or depression together with one or more SUDs.

Results

We included 55 patients in the IG and 21 in the CG. A linear multilevel model was used. Both groups reduced their alcohol and substance use during the trial, while there was no change in psychiatric symptoms in either group. However, the IG had a greater increase in motivation for substance use treatment after 12 months than had the CG with an estimate of 1.76, p = 0.043, CI95% (0.08; 3.44) (adjusted analyses). There were no adverse events.

Conclusions

Integrated treatment is effective in increasing the motivation for treatment amongst patients with anxiety and/or depression together with SUD in outpatient clinics.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00447733

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Substance use disorders (SUD) are among the most common mental disorders (MD) with lifetime prevalence between 15 and 27% [1–3]. A high comorbidity between MD and SUD is established from numerous studies [1, 4–7]. This comorbidity is associated with poorer effect of treatment resulting in poorer psychosocial functioning, a higher number of days in treatment, higher attrition from treatment, more admissions, and a higher burden of disease from both their MD and SUD [8–14]. By SUD we refer to abuse and dependence of both alcohol and illegal substances.

One of the difficulties in treating this comorbidity is that treatment services may lack sufficient combined expertise to treat both types of disorders [15]. This has often resulted in sequential or parallel treatment approaches, which tend to result in poor treatment outcomes, [12, 16–18]. To overcome these difficulties, the Integrated Treatment (IT) approach was developed in the United States at the end of the 1980’s [18, 19] and clinical guidelines to this treatment were later described by Minkoff [20]. The main purpose of this approach is to offer the patient a combined treatment for both the MD and the SUD by the same therapist or therapeutic team, at the same site at the same time. This treatment should be comprehensive, assertive, focusing on both rehabilitation and harm-reduction, having a long-term perspective and use multiple, evidence based therapeutic modalities like Motivational Interviewing (MI) [21–23] and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) [24, 25]. Most clinical guidelines for the treatment of comorbid MD and SUD are recommending a combination of MI and CBT [26–29].

However, most of the research on the effectiveness of IT has been conducted on patients with SUD co-occurring with severe mental disorders. Less is known about the effectiveness of IT for patients with SUD co-occurring with less severe mental illnesses such as anxiety and affective disorders without psychosis. The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of IT for patients with SUD together with anxiety and/or depression in psychiatric outpatient clinics on the following parameters:

-

1)

The use of alcohol and other substances.

-

2)

The severity of psychiatric symptoms.

-

3)

The client’s motivation for changing his/her substance use behaviour.

Methods

Design

The study compares the effectiveness of Integrated Treatment (IT) to treatment as usual (TAU) in the psychiatric outpatient clinics of Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs). To obtain external validity, we chose a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. In order to acquire the calculated sample-size, we chose to run a multi-centre study. As contamination of knowledge between therapists and patients between groups was an obvious risk, we decided to randomize on centre-level. Blinding was judged impossible and therefore the allocation to treatment conditions was open at inclusion. Five CMHCs were drawn to the intervention group and four CMHCs to the control group. For more details see a previous paper [30].

Participants

Patients were sampled from psychiatric outpatient clinics at 9 CMHCs located in the south, eastern and central Norwegian Regional Health Trusts. The CMHCs are part of the specialist level treatment services located in both urban and rural parts of Norway. The patients are generally referred by general practitioners, emergency rooms and inpatient hospital departments for outpatient specialist psychiatric treatment and follow-up. People with anxiety and depression are predominantly referred by their general practitioners.

The inclusion criteria were: new referrals, above 18 years of age, anxiety disorder and/or depression with or without a personality disorder together with a disorder of abuse or dependence from drugs or alcohol. The exclusion criteria were: psychotic disorder, except episodic drug induced psychosis, planning to move away from the catchment area during the 12 months duration of the trial, not able to speak or read Norwegian, disorder of abuse/dependence of benzodiazepines or nicotine as the only substance use disorder and acute illness that required immediate treatment. Those who had an acute illness could be included in the trial after receiving the acute intervention if they were referred back to the outpatient clinic for regular treatment. Participants who provided informed consent to participate and completed the baseline assessments were included in the study.

Sample size

At the time of planning the study there were no published effect-sizes available from studies comparing the effects of IT with TAU. We therefore computed a within-group effect-size based on changes from baseline to follow-up in the absence of a control group in a treatment study evaluating the effects of comprehensive individual and group treatment [31]. The effect-size in this study was modest (0.57), but with a 5% alpha level and 80% power, the minimum number to treat was 78 patients (i.e., N = 36 in each group). With 90% power the number was 108 patients. We expected between 20 and 30 percent dropout for this group of patients from treatment and assessments, and therefore planned to include a total of 150 patients in the study.

Interventions

In both groups the therapists were expected to provide evidence based treatment for the psychiatric disorder of the patient, including psychopharmacological treatment. The use of such medications was therefore not a focus of the study.

The specific background and work-experience of the therapists in this study was not recorded. Generally, the therapists at CMHCs come from different backgrounds; psychologists and medical doctors in addition to nurses and social workers specialising in psychotherapy.

In the intervention group, three to five therapists at each CMHC and their local trial administrators received training in IT. This consisted of 35 hours of training in Motivational Interviewing (MI), Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), involving families and advice on pharmacological treatment. The training was repeated after 6 and 12 months. The local trial administrators and therapists were encouraged to have regular peer-group meetings at their CMHC. The investigators had regular contact with the local trial administrators by phone, e-mails and visits at the CMHCs for support.

The patients in the intervention group received IT for both their psychiatric disorder and their substance use disorder (SUD). The IT consisted of the treatment modalities CBT and MI. In addition, the therapists were to involve the patient’s family and have a more active attitude towards the patient in regard to getting the patient into treatment and continuing treatment, for example by calling or visiting the patient on “no show”. The services should also be comprehensive, i.e. that the services should be directed against a broad array of areas of functioning that are frequently impaired in clients with co-occurring mental and SUD such as housing, vocational functioning, ability to manage the psychiatric illness and family and social relationships [25]. The treatment was not manualized although a descriptive treatment guide was provided.

In the control group, the patients received treatment as usual (TAU). TAU is a difficult term to define as it depends greatly on the preference, skills, knowledge and resources of the therapists delivering it [32]. Commonly, the treatment methods used in CMHCs include psychodynamic and cognitive therapies used with an eclectic approach tailored to meet the differential needs of the individual patient. However, traditionally the treatments given at psychiatric outpatient clinics have focused mainly on the psychiatric disorders, and given little attention to the SUD.

Procedures

We trained and paid one therapist at each CMHC to administer the project locally. These local trial administrators had 3 days of training on how to run the project and the instruments used for screening and assessments. Their scoring of case-vignettes with the EuropASI, chapter E, [33, 34] was evaluated by a certified teacher. The trial administrators assessed all participants at baseline, 6 and 12 months of follow-up, while the initial screening was conducted by the therapists that the patients were referred to.

All new referrals to the psychiatric outpatient clinics of the CMHCs during a defined time period were to be screened with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) [35] and the Drug Use Disorder Identification Test (DUDIT) [36] to identify individuals that may have a problematic use of substances. The cut offs for the AUDIT were set to 6 for women and 8 for men [37]. The cut offs for the DUDIT were set to 2 and 6 for women and men respectively [36]. To be able to measure change in substance use during the 12 months of follow-up, the instructions for the AUDIT and the DUDIT were altered to cover substance use during the last 6 months instead of the original last 12 months. New referrals could include patients with a previous treatment history at the CMHC.

Those who scored above the threshold level on either of the screening instruments were to be referred to the local trial administrator for further assessments. Firstly, the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV axis 1 and axis 2 disorders (SCID 1 and SCID 2) [38, 39] were used to assess whether the patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The patients that fulfilled the inclusion criteria without fulfilling any exclusion criteria were included in the study.

At baseline and both follow up interviews the included patients were assessed with the Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90R) [40–42], the European Addiction Severity Index (EuropASI), chapter E, the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) [43, 44], the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS), the Drug Use Scale (DUS) [45, 46], the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (split version) (GAF) [47, 48] and the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS-r) [49]. The assessments with the AUDIT and the DUDIT were repeated at 6 and 12 months of follow up. The SCID 1 and the SCID 2 were conducted at inclusion only.

For more details see a previous article [30].

Outcome measures

To examine the change in the use of substances (alcohol and illegal drugs) during the course of the trial, we used the AUDIT and the DUDIT to assess changes during the last six months and the EuropASI to assess changes during the last 30 days. The response variables from the EuropASI were coded in the following way: ASI-Alcohol = the number of days using alcohol on a regular basis during the last 30 days (question E1 in the EuropASI manual), ASI-Illegal substances = the number of days using any illegal substances during the last 30 days (a sum of the number of days used from question E3-E12 in the EuropASI manual).

To examine the change in psychiatric symptoms in regard to anxiety and depression during the course of the trial, we used the sum scores of the SCL-90R anxiety, depression and general severity indexes.

Integrated Treatment is motivation-based, i.e. adapted to the patient’s motivation for change. This approach is based on the Stages of Change [50, 51] and the closely related Stages of Treatment [52]. We therefore examined how the patient’s motivation for changing substance use behaviours changed during the trial. To measure this we used the Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS-r).

The outcome measures were examined on the individual level.

Data analyses

When comparing the background variables of the two groups the Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann-Whitney-U test was used for skewed continuous variables. The Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical variables. In cases where one or more cells had an expected count less than five, the Fisher’s Exact test was used.

To examine whether there were differences between the two groups in regard to treatment response, we used a linear multilevel model where the different response variables were modelled as a function of group and time and adjusted for covariates. The clustering in the data was accounted for by a random intercept at patient level and at centre level. The primary target of analysis was the interaction between group and time, as this indicates the different treatment responses between groups during the course of the trial. We ran both Intention to treat and Completers analyses.

The intention to treat analyses (ITT) were adjusted with Age and Gender in addition to the following variables: Living alone, Having his/her own apartment, and Having compulsory school only, as these variables showed a statistically significant difference or at least a 10 percent-point difference between groups at baseline. We continued with completers analyses in the same way and adjusted these with Age and Gender in addition to the following variables: Being in a relationship, Having his/her own apartment, Having paid work, and Having compulsory school only or senior high school as these variables showed a statistically significant difference or at least a 10 percent-point difference between the completer groups at baseline. Completers were defined as having received at least 5 sessions and having met for at least 1 follow-up interview. The reason for adjusting for variables that had a 10 percent point difference or more without showing a statistically significant difference between groups is that the material is somewhat small and we wanted to make sure to include all possible confounders.

The residuals were normally distributed for all response variables except for the DUDIT and the ASI variable for illegal substances. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 [53].

Ethics

There was a complete discussion of the study with potential participants and written informed consent was obtained after this discussion. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (REC-East) who approved and monitored the study, and this approval is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Flow of centres and participants and protocol deviations

This was a difficult study to conduct and the challenges we encountered are described in detail in a previous article [30]. Thirty-five CMHCs from 3 out of 5 Regional Health Trusts were invited to participate in the trial but only 9 CMHCs accepted. Two months into the project, one of the centres in the control group resigned. Another centre in the control group did not manage to include any patients during the time span of the trial, leaving 5 centres in the intervention group (IG) and two centres in the control group (CG).

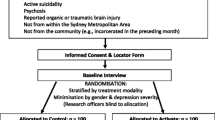

All new referrals were to be screened with the AUDIT and the DUDIT. However, only 35% of the new referrals were screened. Eighteen per cent of the screened patients scored above the cut-off level of the screening instruments, and only 31% of these patients were referred to the local trial administrator for the baseline evaluation (Figure 1). All these challenges delayed the project and are thoroughly discussed in a previous paper [30].

Flowchart of participants. Flowchart of patients in the Intervention Group (IG) and the Control Group (CG) [54].

The initial recruiting period was from April until December 2007 and the follow-up period continued one year after inclusion. As recruitment of patients proved to be slow, the inclusion period was extended by one year. In the end only 76 patients, 55 in the IG and 21 in the CG (ranging from 6 to 16 patients between centres) were enrolled.

After inclusion, 16 patients in the IG and 4 patients in the CG received less than 5 sessions and/or never returned for follow-up interviews. This left 56 completers (CG: 17, IG: 39) (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the number of completers between groups ( 2 = 0.80; df = 1; p = 0.374). There was also no significant difference in the number of sessions (CG: mean 18.9, SD 13.5; IG: mean 14.5, SD 11.3, student’s T-test. -1.4; df = 74; p = 0.160) or in the distribution of sessions received between groups. In both groups the majority of patients received 10 sessions or more (IG: 35 (63.6%), CG: 16 (76.2%) (data not shown).

Comparing completers to non-completers, we found that there were no differences between completers and non-completers in regard to the amount of substances used or the severity of psychiatric symptoms at intake as measured by the outcome measures at baseline (i.e. the AUDIT, the DUDIT, the EuropASI, and the SCID-90r) (data not shown).

Baseline demographics

Table 1 shows the baseline demographics and clinical characteristics between groups in the ITT analyses, i.e. all the included patients. There is a statistically significant difference in age between groups; otherwise, there are no differences between the groups at baseline. About half the patients are male and have paid work. The majority of patients are not in a relationship, are living with someone and have compulsory school only or senior high school. Regarding their diagnoses, the majority of patients have an alcohol use disorder and about half the patients have a personality disorder in addition to their mood and/or anxiety disorder.

Looking at the baseline demographics and clinical characteristics amongst the completers, there is a statistically significant difference between groups in regard to other mental illness (IG: 1/39, CG: 4/17), otherwise the pattern of the baseline characteristics of the completer group is identical with that of the ITT-group (data not shown).

Summary of the results

From the ITT analyses (Table 2) we see that there is a statistically significant reduction in the use of alcohol as measured by the AUDIT in the CG between baseline and 12 months (12 months). However, the additional reduction of alcohol use in the IG is not statistically significant (IG*12 m). There is also a statistically significant reduction in the use of illegal substances as measured by the DUDIT in the CG between baseline and 12 months (12 months). Yet, the additional reduction in the IG is not statistically significant. There is also a statistically significant reduction in the use of alcohol as measured by the ASI in the CG between baseline and 6 months (6 months) and between baseline and 12 months (12 months). However, the additional reduction in the IG during the same time periods is not statistically significant. In summary, both groups reduce their use of alcohol and illegal substances during the 12 month course of the trial, but the IG does not improve significantly more than the CG.

Regarding the change in psychiatric symptoms as measured by the SCL-90r, there are no statistically significant changes from baseline during the course of the trial in either group.

Regarding motivation for treatment, there is a statistically significant interaction between group and time regarding SATS-r (p = 0.003, adjusted, data not shown). Looking at Table 2, this effect is evident after 12 months in both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (IG*12 m). This means that the IG has a greater increase in motivation for substance abuse treatment during the 12 month course of the trial than the CG.

The completer analyses show similar results as the intention to treat analyses on all parameters. Regarding motivation for treatment, there is a statistically significant interaction between group and time regarding SATS-r (p = 0.008, adjusted, data not shown). Looking at Table 3, this effect is evident after 12 months in the unadjusted analyses (IG*12 m) and after 6 and 12 months (IG*6 m, IG*12 m) in the adjusted analyses.

Adverse events

There were no adverse events related to this project. However, one patient included in the IG who was assessed as having a severe SUD and therefore referred to a private addiction treatment centre after receiving 3 sessions at the CMHC, died about 8 months later of an overdose at the private addiction treatment centre between the 6 and 12 month follow-up interviews. He is included in the ITT analyses and regarded as missing at 12 months.

Discussion

This study compared Integrated Treatment with TAU amongst patients in psychiatric outpatient-clinics with anxiety and/or depression together with SUD. Our main findings are that both groups reduce their use of alcohol and other substances, and that the motivation for treatment improves significantly more in the intervention group.

Our first finding is that both treatment groups show a statistically significant decline in the use of alcohol as measured by the AUDIT and the EuropASI and in the use of other substances as measured by the DUDIT. This could mean that both interventions are effective in reducing the use of these substances and that it is more important to receive treatment than which treatment is received. It may also be an effect of the assessment itself and thereby blurring experimental contrast [55, 56]. On the other hand, it may also be a result of type 2 statistical error, as our sample size is quite small. A review from 2009 found a statistically significant reduction in the use of alcohol and/or other substances with the use of Integrated Treatment amongst people with SUD and co-occurring anxiety and/or depression [57] and the use of integrated depression and alcohol treatment with CBT as the main modality has shown a greater reduction in the use of alcohol compared to TAU in patients comorbid of depression and alcohol use disorder [58, 59].

Our second finding is that neither group experienced a significant reduction in psychiatric symptoms. However, the follow-up time of this study was relatively short. A review from 2008 showed that there were improvements in mental health in the long term when MI was combined with CBT [26], which means that these changes may appear later in the course of treatment . It is also possible that the SCL-90r is not sensitive for small changes, especially in this small material. The use of integrated depression and alcohol treatment with CBT as the main modality has shown a greater improvement compared to TAU in depressive symptoms in patients comorbid of depression and alcohol use disorder after 3 and 6 months of follow up [60, 61].

Our final finding is that the intervention group improves significantly in the motivation for treatment. This indicates that Integrated Treatment increases the patients’ motivation to change their addictive behaviours even though we fail to find an additional reduction in the use of alcohol and other substances in the IG. The reason may be that the motivation for change occurs before an actual change in behaviour which may occur later. Several studies have shown that interventions including Motivational Interviewing as one of the therapeutic components have a positive effect on the patients’ motivation for treatment and changing addictive behaviours [26, 60]. Saunders found that even a brief motivational intervention of a 1 hour session was more likely to make a positive shift in the stages of change measure among opiate users at a methadone clinic than in the control group [62]. A review from 2008 showed some effectiveness in the reduction of substance use in the short term when MI was used alone, and that there were improvements in mental health in the long term when MI was combined with CBT [26].

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size is quite small which indicates the possibility of a type 2 statistical error. This is a common problem in this type of treatment research as most randomized clinical trials fail to enrol the target number of patients during the target amount of time [62, 63]. This problem is even more evident in research involving people with SUD that commonly present with high attrition rates from both treatment and clinical trials [64, 65]. Looking at a recent review on integrated psychosocial interventions for patients presenting with co-occurring anxiety and/or depression with SUD, all the included studies had small sample sizes [57]. Secondly, as most new referrals were not screened we lost many potentially eligible participants. We have no way of comparing non-responders with responders. However, we have no indication that there was a systematic selection of those who were screened and those who were not. The representativeness of the participants from the sample of new referrals should therefore not be compromised. Thirdly, we did not focus on the use of psychopharmacological treatment during the course of the trial. If the use of such medications differed between groups, this would alter the results. However, the therapists of all CMHCs are obliged to deliver evidence based treatment for each condition including psychopharmacological treatment. Another limitation is that we did not have a good measure for treatment fidelity. This means that we do not know if the patients in the IG actually received a different treatment than those in the CG. Many studies have shown challenges in implementing new procedures [66, 67]. On the other hand, there was a significant improvement in motivation for treatment in the IG which indicates that there was a difference in the interventions given between groups. Further, one could argue that the trial mainly measures the effectiveness of motivation as patients were classified as completers if they had met at as few as five sessions. On the other hand, in both groups the majority of patients received 10 sessions or more, although such complex conditions might need longer treatment and observation time than the one year follow-up of this and most other trials. Finally, as this is a group randomized trial consisting of only 7 centres, the results could be biased if one of the centres would perform much better or much worse than the other centres. To handle this potential bias, we have used a random intercept at centre level in our linear multilevel model.

To judge whether this intervention is cost-effective given the extra training needed to deliver it, one will need larger studies and a longer time of follow-up.

Interpretation of results

As we found a decline in substance use in both groups, common therapeutic factors are demonstrated but it is unclear whether integrated treatment is more effective in reducing substance use. This might be explained by insufficient power. On the other hand, there was a significant improvement in motivation for treatment in the IG which supports that Integrated Treatment is a fruitful approach when the patient is comorbid with SUD and psychiatric disorders, not only severe mental disorders, but also milder conditions dominated by anxiety and depression. However, these findings should be seen as preliminary and confirmed in larger studies before further conclusions can be drawn.

Generalizability

To provide external validity, we chose a pragmatic RCT design with wider inclusion criteria and few exclusion criteria. The results therefore should be generalizable to the average adult patient population in CMHCs with co-occurring anxiety and/or depression together with SUD.

This article is to a large extent structured as recommended by the Consort group for reporting on group RCTs [68–75].

Conclusions

Integrated treatment is effective in increasing the motivation for treatment amongst patients with anxiety and/or depression together with SUD in outpatient clinics.

Authors’ information

LW is a psychiatrist and PhD-fellow at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, the University of Oslo, and a medical advisor at the Agency of Welfare and Social Services, the City of Oslo. HW is a psychiatrist and professor emeritus at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, the University of Oslo. RG is a psychologist, Head of the Department of Research and Development at the Alcohol and Drug Treatment Health Trust in Central Norway.

Abbreviations

- ASI:

-

Addiction severity index

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol use disorder identification test

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- CG:

-

Control group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMCH:

-

Community mental health centre

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition

- DUDIT:

-

Drug use disorder identification test

- EuropASI:

-

Addiction severity index, European version

- ICD-10:

-

International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th edition

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- IT:

-

Integrated treatment

- ITT:

-

Intention to treat analyses

- MI:

-

Motivational interviewing

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SATS-r:

-

Substance abuse treatment scale revised

- SCID-I:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, axis 1 disorders

- SCID-II:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, axis 2 disorders

- SCL-90r:

-

Symptom check list 90 items revised

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- SUD:

-

Substance use disorder (including abuse and addiction from both alcohol and illegal substances)

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

References

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990, 264: 2511-2518. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendlers KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994, 51: 8-19. 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005, 62: 593-602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996, 66: 17-31.

Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, Bijl R, Borges G, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, DeWit DJ, Kolody B, Vega WA, Wittchen HU, Kessler RC: Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998, 23: 893-907. 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00076-8.

Crome IB: Substance misuse and psychiatric comorbidity: towards improved service provision. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 1999, 6: 151-174. 10.1080/09687639997115.

Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [References]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007, 64: 830-842. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830.

Menezes PR, Johnson S, Thornicroft G, Marshall J: Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illnesses in South London. Br J Psychiatry. 1996, 168 (5): 612-619. 10.1192/bjp.168.5.612.

Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, Clark RE: Substance abuse in schizophrenia: service utilization and costs. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993, 181: 227-232. 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00003.

Baker KD, Lubman DI, Cosgrave EM, Killackey EJ, Yuen HP, Hides L, Baksheev GN, Buckby JA, Yung AR: Impact of co-occurring substance use on 6 month outcomes for young people seeking mental health treatment. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007, 41 (11): 896-902. 10.1080/00048670701634986.

Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia. A prospective community study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989, 177: 408-414. 10.1097/00005053-198907000-00004.

Polcin DL: Issues in the treatment of dual diagnosis clients who have chronic mental-illness. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1992, 23: 30-37.

Compton WM, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL: The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2003, 160: 890-895. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890.

Weisner C, Matzger H, Kaskutas LA: How important is treatment? One-year outcomes of treated and untreated alcohol-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2003, 98: 901-911. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00438.x.

Sacks S, Chaple M, Sirikantraporn J, Sacks JY, Knickman J, Martinez J: Improving the capability to provide integrated mental health and substance abuse services in a state system of outpatient care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013, 44: 488-493. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.11.001.

Green AI, Drake RE, Brunette MF, Noordsy DL: Schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007, 164: 402-408. 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.402.

Mangrum LF, Spence RT, Lopez M: Integrated versus parallel treatment of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006, 30: 79-84. 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.004.

Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, Wallach MA: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996, 66: 42-51.

Minkoff K: An integrated treatment model for dual diagnosis of psychosis and addiction. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989, 40: 1031-1036.

Minkoff K: Behavioral health recovery management service planning guidelines co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. In Illinois Department of Human Services’ Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse, The Behavioral Health Recovery Management project, An initiative of Fayette Companies. Peoria, IL: Chestnut Health Systems, Bloomington, IL; and the University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 2001:1–36.

Miller WR: Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1983, 11: 147-172. 10.1017/S0141347300006583.

Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to Change Addictive Behavior. 1991, 72 Spring Street, New York, NY 10012: A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc, The Guilford Press

Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for Change. 2002, 72 Spring Street, New York, NY 10012: A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc, The Guilford Press

Kendall PC: Cognitive-behavioral interventions: theory, research, and procedures. 1979, 111 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10003: Academic Press, Inc

Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, Fox L: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: a guide to effective practice. 2003, 72 Spring Street, New York, NY 10012: A Division of Guilford Publications, Inc, The Guilford Press

Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson SL, Siegfried N, Walter G: Psychosocial interventions for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, 1: CD001088-

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Substance abuse treatment for persons with co-occurring disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP). 2008, Rockville (MD): Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) Series, No. 42. SMA13-3992, Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64197/

Rush B: Best practices concurrent mental health and substance use disorders. Edited by: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. 2002, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Publications Health Canada

Kirkhei I, Leiknes KA, Hammerstrom KT, Larun L, Bramnes JG, Grawe RW, Haugerud H, Helseth V, Landheim A, Lossius K, Waal H: Dual diagnoses - Severe Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorder. Part 2 - Effect of psychosocial interventions. 2008, No. 25, Oslo: Report from the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services Systematic review

Wüsthoff LE, Waal H, Gråwe RW: When Research Meets Reality; Lessons Learned From a Pragmatic Multisite Group-Randomized Clinical Trial on Psychosocial Interventions in the Psychiatric and Addiction Field. Subst Abus. 2012, 6: 95-

Grawe RW, Hagen R, Espeland B, Mueser KT: The better life program: effects of group skills training for persons with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. J Ment Health. 2007, 16: 625-634. 10.1080/09638230701494886.

Hotopf M: The pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2002, 8: 326-333. 10.1192/apt.8.5.326.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980, 168: 26-33. 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006.

Kokkevi A, Hartgers C: EuropASI: European Adaptation of a Multidimensional Assessment Instrument for Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Eur Addict Res. 1995, 1: 208-210. 10.1159/000259089.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M: Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993, 88: 791-804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x.

Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F: Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res. 2005, 11: 22-31. 10.1159/000081413.

Reinert DF, Allen JP: The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007, 31: 185-199. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). 2002, New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute

First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). 1997, Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc

Derogatis LR, Cleary PA: Confirmation of Dimensional Structure of Scl-90 - Study in Construct-Validation. J Clin Psychol. 1977, 33: 981-989. 10.1002/1097-4679(197710)33:4<981::AID-JCLP2270330412>3.0.CO;2-0.

Derogatis LR, Cleary PA: Factorial invariance across gender for the primary symptom dimensions of the SCL-90. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1977, 16: 347-356. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1977.tb00241.x.

Derogatis LR: The SCL-90 Manual I: Scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90. 1977, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Unit

Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, Park SB, Hadden S, Burns A: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Research and development. Br J Psychiatry. 1998, 172: 11-18. 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11.

Wing J, Curtis RH, Beevor A: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) - Glossary for HoNOS score sheet. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 174: 432-434. 10.1192/bjp.174.5.432.

Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, Beaudett MS: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990, 16: 57-67. 10.1093/schbul/16.1.57.

Mueser KT, Drake RE, Clark RE, McHugo GJ, Mercer-McFadden C, Ackerson TH: Toolkit on evaluating substance abuse in persons with severe mental illness. 1995, Cambridge, MA: Human Services Research Institute

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). 2000, Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association

Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992, 149: 1148-1156.

McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, Ackerson TH: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995, 183: 762-767. 10.1097/00005053-199512000-00006.

Connors GJ, Donovan DM, DiClemente CC: Substance Abuse Treatment and the Stages of Change. 2001, New York: Guilford Press

Prochaska JO: Systems of Psychotherapy: a transtheoretical analysis. 1984, Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press

Osher FC, Kofoed LL: Treatment of patients with psychiatric and psychoactive substance abuse disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989, 40: 1025-1030.

IBM Corp: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. 2011, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp

Wüsthoff LE, Waal H, Gråwe RW: When Research Meets Reality- lessons Learned From a Pragmatic Multisite Group- Randomized Clinical Trial on Psychosocial Interventions in the Psychiatric and Addiction Field. Substance Abuse. 2012, 6: 95-106.

Baker A, Turner A, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Lewin TJ: The long and the short of treatments for alcohol or cannabis misuse among people with severe mental disorders. Addict Behav. 2009, 34: 852-858. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.02.002.

Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML: Assessment may conceal therapeutic benefit: findings from a randomized controlled trial for hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2007, 102: 62-70. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01632.x.

Hesse M: Integrated psychological treatment for substance use and co-morbid anxiety or depression vs. treatment for substance use alone. A systematic review of the published literature. BMC Psychiatry. 2009, 9: 6-10.1186/1471-244X-9-6.

Watkins KE, Hunter S, Hepner K, Paddock S, Zhou A, de la Cruz E: Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for clients with major depression in residential substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2012, 63: 608-611.

Baker AL, Kavanagh DJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Hunt SA, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ, Connolly J: Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: short-term outcome. Addiction. 2010, 105: 87-99. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x.

Miller WR: Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996, 21: 835-842. 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5.

Saunders B, Wilkinson C, Phillips M: The impact of a brief motivational intervention with opiate users attending a methadone programme. Addiction. 1995, 90: 415-424. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03788.x.

English R, Lebovitz Y, Griffin R: Forum on Drug Discovery, Development, and Translation Board on Health Sciences Policy. Transforming Clinical Research in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities: Workshop Summary. 2010, Washington, D.C: National Academies Press, Institute of medicine of the National Academies

Rendell JM, Licht RW: Under-recruitment of patients for clinical trials: an illustrative example of a failed study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007, 115: 337-339. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01019.x.

Lehman AF, Herron JD, Schwartz RP, Myers CP: Rehabilitation for adults with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. A clinical trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993, 181: 86-90. 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00003.

Burnam MA, Morton SC, McGlynn EA, Petersen LP, Stecher BM, Hayes C, Vaccaro JV: An experimental evaluation of residential and nonresidential treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Addict Dis. 1995, 14: 111-134.

Grol R, Grimshaw J: From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003, 362: 1225-1230. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1.

Hannes K, Pieters G, Goedhuys J, Aertgeerts B: Exploring barriers to the implementation of evidence-based practice in psychiatry to inform health policy: a focus group based study. Community Ment Health J. 2010, 46: 423-432. 10.1007/s10597-009-9260-1.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG: The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001, 357: 1191-1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04337-3.

Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T: The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001, 134: 663-694. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012.

Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG: CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004, 328: 702-708. 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P: Methods and processes of the CONSORT Group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: W60-W66.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D: CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010, 7: e1000251-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG: CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010, 63: e1-e37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004.

Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG, Schulz KF: CONSORT for reporting randomised trials in journal and conference abstracts. Lancet. 2008, 371: 281-283. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61835-2.

Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG, Schulz KF: CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2008, 5: e20-10.1371/journal.pmed.0050020.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/67/prepub

Acknowledgements

Amund Aakerholt at The Centre of Competence for Addiction Issues – region east, and Alcohol and Drug Research Western Norway, has contributed to the planning and implementation of the study together with the acquisition of data.

The local trial administrators Erik-Kristian Zahl-Pettersen, Guro Svane Bratset, Line Aksdal Eriksen, Claes Brisendal, Torunn Hansen Melø, Arve Forbord, Turid Alvestad Tomren and Vigdis Troøyen Foseide are acknowledged for their enormous efforts in running the trial, assessing patients and collecting data at their respective CMHC.

All the therapists, leaders and other staff at the following Community Mental Health Centres: DPS Fredrikstad, Lillestrøm DPS, Tiller DPS, Allmennpsykiatrisk poliklinikk Levanger, DPS Molde, Stjørdal DPS, Ålesund DPS and Orkdal DPS are acknowledged for their contribution to and support of the study.

All the therapists in the intervention group are acknowledged for their time, patience and effort in learning and using Integrated Treatment on their patients.

All the patients at the participating CMHCs are acknowledged for their time and patience in participating in the study.

Helge Haugerud at The Regional Centre for Co-occurring Disorders of Substance Abuse and Mental Health has contributed to the planning of the study.

Magne Thoresen, Professor and Head of the Department of Biostatistics, University of Oslo, has given valuable help in choosing statistical methods and interpreting the results.

Desiree Madah-Amiri, at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, has given valuable help in the final revision of the manuscript.

The study was based on a consortium between The Regional Centre for Co-occurring Disorders of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, The Centre of Competence for Addiction Issues – region east, The University of Oslo, and Sintef Health.

The study was funded by The Research Council of Norway, The Regional Centre for Co-occurring Disorders of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, and The Centre of Competence for Addiction Issues – region east.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

All the authors fulfil the Vancouver requirements for authorship. RG and HW have been involved in the conception and design of the study. RG and LW have been involved in the acquisition of the data. HW and LW have been involved in interpreting the data. LW has drafted the manuscript. All authors have been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the version to be published.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wüsthoff, L.E., Waal, H. & Gråwe, R.W. The effectiveness of integrated treatment in patients with substance use disorders co-occurring with anxiety and/or depression - a group randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 14, 67 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-67

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-67