Abstract

Background

Leptin and ghrelin have been implicated in the pathogenesis of major depression. However, evidence is lacking among apparently healthy people. This study examined the relationship of these appetite hormones to depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 2009 among 497 Japanese employees (287 men and 210 women) aged 20–68 years. Fasting serum leptin and ghrelin levels were measured using a Luminex suspension bead-based multiplexed array. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for depressive symptoms with adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

The prevalence of depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥16) was 26.5% and 33.3% among men and women, respectively. Women in the middle and highest tertiles of leptin levels showed lower odds for depressive symptoms compared with those in the lowest level, although the trend association was not statistically significant (P trend = 0.14). Higher ghrelin levels were associated with increased odds for depressive symptoms in women (P trend = 0.02). The multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI) of having depressive symptoms for the lowest through highest tertiles of ghrelin levels were 1.00 (reference), 1.71 (0.76 - 3.86), and 2.69 (1.16 - 6.28), respectively. Neither leptin nor ghrelin was associated with depressive symptoms in men.

Conclusions

Results suggest that lower leptin and higher ghrelin levels may be related to higher prevalence of depressive status among Japanese women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression is an important public health issue, affecting approximately 350 million people worldwide, and is a significant contributor to the global burden of disease [1, 2]. It is an illness that impairs an individual’s ability to function at work or cope with daily life [3, 4]. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide, which is responsible for the loss of approximately one million lives every year [2]. In Japan, the number of patients identified with depression has been increasing [5] and Japan has one of the world’s highest suicide rates [6]. New insights into the pathogenesis of depression to support the development of preventive strategies for this illness are therefore essential.

Leptin, an anorexigenic hormone produced by adipose tissue, regulates food intake and body weight [7, 8], while ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone produced mainly in the stomach, also plays a role in regulating appetite, weight and body fat [8, 9]. These hormones have opposite effects, not only on regulating appetite and body weight, but also on mood and stress pathways. In animal models of depression, administration of leptin has been shown to improve depressive behaviors and exert antidepressant-like effects [10, 11]. Similarly, a potential role of ghrelin in the regulation of stress and anxiety is suggested [12]. Acute stress increases ghrelin secretion in rats [13] and central ghrelin administration increases anxiety and depressive-like behaviours [14].

Appetite and food intake are often altered in patients with major depression. Although weight loss has been recognized as a typical sign of depression, weight gain has also been observed [15]. Chronic stress or atypical depression may cause weight gain through increased ingestion of calorie dense foods [16]. In addition, some anti-depressive drugs are known to induce weight gain [17]. Given important roles of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of appetite and weight, depressive status as well as medication for depression may also influence the levels of these hormones.

Several neural pathways linking leptin and ghrelin to mental disorders have been suggested. Leptin may have a role in modulating monoamine neurotransmission [18, 19]. Ob/ob mice lacking leptin had lower dopamine release and decreased concentrations of tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, in the nucleas accumbens, and these effects were reversed by leptin treatment [18]. Hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a common feature of depression [20] and accumulating evidence suggests that leptin reduces HPA activity [21, 22]. Neurotrophic actions of leptin may be another mechanism explaining the relationship with depressive disorders. In animal studies, leptin has been shown to reduce depressive behaviors through the upregulation of brain-derived neurotropic factor in the hippocampus [23]. In contrast, ghrelin suppresses serotonin neurotransmission [24] and increases HPA axis activity [25, 26]. Ghrelin’s suppressive effect on the central release of monoamines and stimulatory action on the HPA axis suggest that rising ghrelin may contribute to the mechanisms responsible for the development of depression.

Several studies in humans have examined the association between leptin and depression, but their results are inconsistent. Some clinical studies have reported lower levels of leptin among depressed individuals [27–31] and suicide attempters [32], while others have found either no difference [33] or even higher blood levels of leptin in depressed individuals [34–36], as compared with healthy controls. Inconsistent findings have also been observed regarding the association between ghrelin levels and depression [27, 30, 37–39] and suicide attempters [40]. The results of these clinical studies may reflect changes of weight and appetite as a result of depression [15, 33]. Only two studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the relationship between circulating leptin levels and depression in the general population: one in women only [41] and another in elderly men and women [42]. Moreover, although some data suggest racial differences in blood levels of leptin and ghrelin [43, 44], studies on this issue have been limited to Westerners. Similarly, given a large difference in blood leptin and ghrelin levels between men and women [31, 37, 42], there may be a sex difference in the association between these hormones and depression. Here, we examined the association of serum leptin and ghrelin levels and depressive symptoms among Japanese men and women.

Methods

Study procedure and subjects

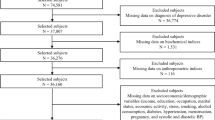

This study was conducted in July and November 2009 among employees of two municipal offices in northeastern Kyushu, Japan, as described elsewhere [45]. At the time of the periodic health examination, all full time workers (n = 605), except those on long sick or maternity leave, were invited to participate in this study. Participants were asked to fill in the survey questionnaires beforehand, which were checked by research staff for completeness and, where necessary, clarified by questioning the subjects during the examination. Data were also obtained from routine health checkup, including anthropometric measurements, biochemical data, and information about medical history, smoking, and alcohol drinking. Blood and urine specimens were also collected. The Ethics Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Japan, approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the survey.

Of 605 eligible employees, 567 subjects (325 men and 242 women) aged 20–68 years participated in the survey (response rate 94%). We excluded 32 subjects with a history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or cancer. We further excluded 22 subjects without leptin and ghrelin measurement and 25 subjects whose blood sample was not obtained in fasting status. Some subjects fell into more than one exclusion criteria. Finally, 497 subjects (287 men and 210 women) remained for this study.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Japanese version [46] of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale [47]. This scale consists of 20 questions addressing 6 symptoms of depression experienced by participants during the preceding week: depressed mood, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, helplessness or hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disorders. Each question is scored on a scale of 0–3 according to the frequency of the symptom, and the total score ranges from 0 to 60. The criterion validity of the CES-D scale has been well established both in Western [47] and Japanese [46] subjects. Depressive symptoms were defined as present when subjects had a CES-D score of ≥16. Another cutoff value for the definition of depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 19) that may be more suitable for Japanese was also used [48].

Blood measurements

Blood samples were obtained after an overnight fast mostly in the morning between 8:30 and 12:00 a.m. Venus blood (7 mL) was drawn in tube (without addition of protease inhibitors) and then taken in a cooler box to a laboratory. The blood was centrifuged for 10 minutes and was divided into a maximum of six tubes (0.5 mL each) at –80°C or –20°C until analysis. About 15 μL of serum was used to analyze leptin and ghrelin. To quantify serum concentrations of leptin and ghrelin, a Luminex suspension bead-based multiplexed array was performed using Bio-Plex 3D suspension array system and Bio-Plex Pro human diabetes assay panel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The intra-assay coefficients of variation were 11% for leptin and 5% for ghrelin.

Other variables

Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with the subjects standing without shoes. Body weight in light clothes was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the body weight (kg) divided by the square of the body height (m2). Smoking status, alcohol drinking, marital status, job title, job position, and non-occupational physical activity were self-reported in the lifestyle questionnaire. Job title was used to create categories for occupational physical activity; sedentary work included managerial and clerical jobs, whereas physically active work included child-care, school lunch cooking, and technical jobs at water, sewer, and waste treatment facility. Non-occupational physical activity was expressed as daily minutes spent for walking or cycling during commute to or from work and weekly hours engaged in each of five different activities (walking, low-, moderate-, and high-intensity activities, and gardening). The sum of time spent for all the non-occupational activities were expressed in hours per week.

Statistical analyses

Because the association of leptin and ghrelin with depressive symptoms may not be linear, we used tertile categories of leptin and ghrelin. Characteristics of study subjects across tertiles of leptin or ghrelin level and their trend association were assessed using linear regression analysis for continuous variables or Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for categorical variables. Serum leptin and ghrelin levels were considerably higher in women than men, thus we present the data separately. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of depressive symptoms for the tertiles of leptin and ghrelin levels, taking the lowest tertile as a reference. We adjusted for a range of potential confounding factors, which were a priori selected with reference to reviews on risk factor for depression [49, 50] as well as our previous works on folate and ferritin [51, 52] . The two participating offices in the present study are denoted as workplace A and workplace B. In the first model, we adjusted for age (year, continuous), and workplace (A or B). In the second model, we further adjusted for marital status (married or unmarried), job position (low, medium, or high), occupational physical activity (active or sedentary), non-occupational physical activity (0, >0 to <2 hours/week, or ≥2 hours/week), current smoking (yes or no), alcohol drinking (yes or no), total energy intake (kcal/day, continuous), BMI (kg/m2, continuous), logarithmic serum ferritin (μg/L, continuous), and logarithmic serum folate (ng/mL, continuous). Trend association was assessed by assigning ordinal numbers 1–3 to tertiles of leptin and ghrelin levels. The effect modification by sex on the association between leptin, ghrelin, and depressive symptoms was assessed using the likelihood ratio test in the full adjusted model. Two-sided P values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using statistical software Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas USA).

Results

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 26.5% and 33.3% among men and women, respectively using the standard cutoff value (CES-D ≥ 16). Mean values of serum leptin and ghrelin levels were significantly higher in women than men (mean leptin: men, 1.88 ng/mL, women, 3.45 ng/mL; mean ghrelin: men, 0.59 ng/mL, women, 0.82 ng/mL) (P <0.001 for both). In men, the median and range of leptin (ng/mL) from lowest through highest tertiles were 0.56 (0.11 - 1.03), 1.36 (1.04 - 1.96), and 3.16 (1.97 - 10.64). The corresponding values (ng/mL) in women were 0.96 (0.08 - 1.95), 2.95 (1.96 - 3.89), and 5.65 (3.90 - 16.55). With regard to ghrelin, median and range (ng/mL) from lowest through highest tertile were 0.32 (0.12 - 0.41), 0.54 (0.42 - 0.72), and 0.89 (0.73 - 2.84) in men, and were 0.41(0.17 - 0.63), 0.78 (0.64 - 0.92), and 1.20 (0.93 - 3.21) in women.

Subjects’ characteristics according to tertiles of leptin in men and women are presented in Table 1. Men with higher leptin levels were more likely to be older and had higher BMI, but were less likely to be in a low job position. In women, participants with higher leptin levels had higher BMI and had a higher energy intake. Subjects’ characteristics across tertiles of ghrelin in men and women are presented in Table 2. In both men and women, subjects with higher ghrelin had lower BMI, but were more likely to be an alcohol drinker.

The odds ratios for depressive symptoms according to tertiles of leptin and ghrelin are presented in Table 3. Women in the middle and highest tertiles of leptin levels showed lower odds for depressive symptoms compared with those in the lowest level, although the trend association was not statistically significant (P trend = 0.14). In the multivariable adjusted model, compared with women in the first tertile of leptin, those in the second and third tertile had 59% (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.17-0.97) and 53% (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.18-1.23) lower odds for depressive symptoms, respectively. A similar association was observed between leptin and depressive symptoms, when the presence of depressive symptoms was defined as CES-D ≥ 19. In women, the multivariable adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for depressive symptoms in first, second, and third tertiles of leptin were 1.00 (reference), 0.34 (0.13-0.92), and 0.51 (0.18-1.47), respectively (P trend = 0.16). In men, there was no association between leptin levels and depressive symptoms using the two different cut off values of depressive symptoms.

In multivariable adjusted models, higher ghrelin levels were associated with increased odds for depressive symptoms in women (P trend = 0.02) (Table 3). The multivariable adjusted ORs (95% CIs) of depressive symptoms for the lowest through highest tertiles of ghrelin levels were 1.00 (reference), 1.71 (0.76-3.86), and 2.69 (1.16-6.28), respectively. Similarly, when another cutoff value for the definition of depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥19) was used, the ORs (95% CIs) for lowest through highest tertiles of ghrelin were 1.00 (reference), 1.45 (0.60-3.49), and 2.76 (1.71-5.38), respectively, in women (P trend = 0.03). In men, ghrelin levels were not associated with depressive symptoms.

Discussion

In an apparently healthy Japanese working population, women with higher ghrelin levels had higher odds for depressive symptoms than those with lower ghrelin levels, whereas women in the upper two-thirds of leptin levels had lower odds for depressive symptoms than those in the lowest third. In men, neither leptin nor ghrelin was associated with depressive symptoms. To our knowledge, this is the first study among Asians to examine the association between leptin and ghrelin levels and depressive status in the general population.

Our finding regarding leptin is in line with a previous clinical study [31], wherein leptin levels were significantly lower in female depressed patients than healthy controls, but the association was null in men. The present findings also concur with another study among suicide attempters [32], reporting that depressed women had lower leptin levels than non-depressed women, whereas no significant association was observed in men. As observed previously [31, 32], we also found that women, as compared with men, had higher levels of leptin. Because we found no reduction in the odds for men in the highest tertile of leptin (a level comparable to women in the middle tertile of leptin showing a reduction in the odds for depression), the gender difference in leptin levels may not account for the null finding in men. Alternatively, there may be a gender difference in the relationship between leptin and depression.

The finding of fewer depressive symptoms in women with higher levels of leptin is at odds with the results of two previous population-based studies. In a previous US study [42], leptin was not associated with depression in women, but higher leptin was associated with increased risk of depression in men with high visceral fat. In an Australian study [41], women with a lifetime history of depression had elevated levels of leptin, and leptin levels predicted the subsequent development of de novo major depressive disorder over five years of follow-up, independently of BMI. Given that obesity is associated with inflammation [53], which has been linked to both the risk for depression [54] and the development of leptin resistance [55], the positive association observed in these Western studies may be ascribed to a higher BMI of the participants. In a Japanese population, which has on average much lower BMI than Westerners, the association between leptin and mood disorder may be less likely to be influenced by such inflammation-depression pathway.

On the basis of contradictory data among epidemiological studies on the relationship between leptin and depressive symptoms, Lu et al. [10] suggested that both leptin insufficiency and leptin resistance might contribute to alterations of affective status. This could explain, at least in part, the non-linear relationship between leptin and depressive symptoms in the present study. We found no further reduction in the odds for depressive symptoms among women in the highest tertile of leptin, who had a higher mean BMI than those in the middle tertile of leptin, suggesting that reduced leptin sensitivity may mitigate any possible protective effects of leptin on depression in this group.

Ghrelin levels were significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms among women in the present study. At variance with our finding, a clinical study reported that ghrelin level was not associated with depressive symptoms in women [30]. Likewise, other clinical studies found no significant difference in ghrelin levels between patients with major depression and healthy controls [27, 37, 38]. Another study reported significantly lower levels of ghrelin in depressive patients than in healthy controls [39]. However, in another study, suicide attempters had significantly higher levels of ghrelin than healthy controls [40]. Such inconsistency among clinical studies may be ascribed to the influence of depression on ghrelin levels or methodological shortcomings, such as small sample size and the lack of control for potential confounders including BMI and lifestyle factors. Population-based studies are needed to explore the association between ghrelin and depression.

A similar association between leptin, ghrelin, and depressive symptoms was observed when the presence of depressive symptoms was defined by two different cutoffs. Although the cutoff for CES-D ≥ 16 has been widely recommended, the cut off CES-D ≥ 19 has been recommended based on a validation study among Japanese workers [48]. Such a higher cutoff is reasonable for Japanese given that Japanese tend to express their positive emotion in a modest manner, potentially leading to a higher score on depression scales [56]. The consistency in relationships between leptin, ghrelin, and depressive symptoms using two different cutoffs of CES-D in defining depressive symptoms in our study strengthens our findings.

Our findings linking depression with higher level of leptin and lower levels of ghrelin seems reasonable given that leptin treatment improves monoamine neurotransmission [18, 19] and lessens HPA axis [21, 22], whereas ghrelin has opposite effects [24–26]. Because depression often results in profound alterations in dietary intakes, with either increased or decreased appetite, the observed differences in leptin and ghrelin levels between those with and without depression symptoms may simply reflect such change in dietary habit. However, this is a less plausible explanation for the present finding, as we found no significant differences in energy intake and BMI in subjects with depressive symptoms compared to those without.

Major strengths of the present study include the high study participation rate (94%), the exclusion of participants with history of chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, which may alter the levels of leptin or ghrelin, and the adjustment for potential cofounding variables. Despite these strengths, our study had several limitations that warrant mention. Firstly, data derived from a cross-sectional study cannot shed light on the direction of the relationship and it is not possible to determine causality. Secondly, ghrelin and leptin were measured only a single time point, which limits the accuracy of the measurement. However, Lee et al. [57] showed that adipokine levels measured in a single sample had a high correlation with the mean of the remaining three seasonal samples. Thirdly, because of the relatively small sample, statistical power might not have been sufficient to detect a moderate association. Fourthly, our study population was apparently healthy population and hence symptoms of depression in our sample were less than one would observe in clinical populations of patients with depression. Finally, our study was conducted in selected municipal offices, thus the findings may not be generalizable to the whole population of Japanese adults.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study show that higher ghrelin levels are associated with increased prevalence of depressive symptoms in women. Longitudinal studies with large sample size, assessments of serum leptin and ghrelin at multiple times point, and follow-up assessments for clinical depression are needed to confirm the present findings.

References

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrew KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2197-2223.

World Health Organization: 2012, http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/en/ (cited at 1 August 2014)

Bijl RV, Ravelli A: Current and residual functional disability associated with psychopathology: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Psychol Med. 2000, 30 (3): 657-668.

Kruijshaar ME, Hoeymans N, Bijl RV, Spijker J, Essink-Bot ML: Levels of disability in major depression: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). J Affect Disord. 2003, 77 (1): 53-64.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare: Patients survey 2011. 2011, in Japanese

World Health Organization: 2008, http://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/suicide_prevention_asia.pdf (cited at 4 August 2014)

Jequier E: Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002, 967: 379-388.

Meier U, Gressner AM: Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism: review of pathobiochemical and clinical chemical aspects of leptin, ghrelin, adiponectin, and resistin. Clin Chem. 2004, 50 (9): 1511-1525.

Tschop M, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML: Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes. 2001, 50 (4): 707-709.

Lu XY: The leptin hypothesis of depression: a potential link between mood disorders and obesity?. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007, 7 (6): 648-652.

Lu XY, Kim CS, Frazer A, Zhang W: Leptin: a potential novel antidepressant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103 (5): 1593-1598.

Chuang JC, Zigman JM: Ghrelin’s roles in stress, mood, and anxiety regulation. Int J Pept. 2010, 2010:

Carlini VP, Monzon ME, Varas MM, Cragnolini AB, Schioth HB, Scimonelli TN, De Barioglio SR: Ghrelin increases anxiety-like behavior and memory retention in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002, 299 (5): 739-743.

Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, Yuzuriha H, Nagata T, Fujimiya M, Katsuura G, Makino S, Fujino MA, Kasuga M: A role of ghrelin in neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress in mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2001, 74 (3): 143-147.

Weissenburger J, Rush AJ, Giles DE, Stunkard AJ: Weight change in depression. Psychiatry Res. 1986, 17 (4): 275-283.

Schellekens H, Finger BC, Dinan TG, Cryan JF: Ghrelin signalling and obesity: At the interface of stress, mood and food reward. Pharmacol Ther. 2012, 135 (3): 316-326.

Mann JJ: Drug therapy - The medical management of depression. New Engl J Med. 2005, 353 (17): 1819-1834.

Fulton S, Pissios P, Manchon RP, Stiles L, Frank L, Pothos EN, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS: Leptin regulation of the mesoaccumbens dopamine pathway. Neuron. 2006, 51 (6): 811-822.

Hommel JD, Trinko R, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Liu ZW, Gao XB, Thurmon JJ, Marinelli M, DiLeone RJ: Leptin receptor signaling in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates feeding. Neuron. 2006, 51 (6): 801-810.

De Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F: Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005, 6 (6): 463-475.

Stephens TW, Basinski M, Bristow PK, Bue-Valleskey JM, Burgett SG, Craft L, Hale J, Hoffmann J, Hsiung HM, Kriauciunas A, Mackellar W, Jr Rosteck PR, Schoner B, Smith D, Tinsley FC, Zhang XY, Heiman M: The role of neuropeptide Y in the antiobesity action of the obese gene product. Nature. 1995, 377 (6549): 530-532.

Licinio J, Mantzoros C, Negrao AB, Cizza G, Wong ML, Bongiorno PB, Chrousos GP, Karp B, Allen C, Flier JS, Gold PW: Human leptin levels are pulsatile and inversely related to pituitary-adrenal function. Nat Med. 1997, 3 (5): 575-579.

Yamada N, Katsuura G, Ochi Y, Ebihara K, Kusakabe T, Hosoda K, Nakao K: Impaired CNS leptin action is implicated in depression associated with obesity. Endocrinology. 2011, 152 (7): 2634-2643.

Brunetti L, Recinella L, Orlando G, Michelotto B, Di Nisio C, Vacca M: Effects of ghrelin and amylin on dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin release in the hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002, 454 (2–3): 189-192.

Mozid AM, Tringali G, Forsling ML, Hendricks MS, Ajodha S, Edwards R, Navarra P, Grossman AB, Korbonits M: Ghrelin is released from rat hypothalamic explants and stimulates corticotrophin-releasing hormone and arginine-vasopressin. Horm Metab Res. 2003, 35 (8): 455-459.

Kluge M, Schussler P, Zuber V, Yassouridis A, Steiger A: Ghrelin administered in the early morning increases secretion of cortisol and growth hormone without affecting sleep. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2007, 32 (3): 287-292.

Emul HM, Serteser M, Kurt E, Ozbulut O, Guler O, Gecici O: Ghrelin and leptin levels in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 31 (6): 1270-1274.

Jow GM, Yang TT, Chen CL: Leptin and cholesterol levels are low in major depressive disorder, but high in schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2006, 90 (1): 21-27.

Kraus T, Haack M, Schuld A, Hinze-Selch D, Pollmacher T: Low leptin levels but normal body mass indices in patients with depression or schizophrenia. Neuroendocrinology. 2001, 73 (4): 243-247.

Lawson EA, Miller KK, Blum JI, Meenaghan E, Misra M, Eddy KT, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Leptin levels are associated with decreased depressive symptoms in women across the weight spectrum, independent of body fat. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012, 76 (4): 520-525.

Yang K, Xie G, Zhang Z, Wang C, Li W, Zhou W, Tang Y: Levels of serum interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1beta, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and leptin and their correlation in depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007, 41 (3): 266-273.

Westling S, Ahren B, Traskman-Bendz L, Westrin A: Low CSF leptin in female suicide attempters with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004, 81 (1): 41-48.

Deuschle M, Blum WF, Englaro P, Schweiger U, Weber B, Pflaum CD, Heuser I: Plasma leptin in depressed patients and healthy controls. Horm Metab Res. 1996, 28 (12): 714-717.

Antonijevic IA, Murck H, Frieboes RM, Horn R, Brabant G, Steiger A: Elevated nocturnal profiles of serum leptin in patients with depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1998, 32 (6): 403-410.

Cizza G, Nguyen VT, Eskandari F, Duan Z, Wright EC, Reynolds JC, Ahima RS, Blackman MR: Low 24-hour adiponectin and high nocturnal leptin concentrations in a case–control study of community-dwelling premenopausal women with major depressive disorder: the Premenopausal, Osteopenia/Osteoporosis, Women, Alendronate, Depression (POWER) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010, 71 (8): 1079-1087.

Gecici O, Kuloglu M, Atmaca M, Tezcan AE, Tunckol H, Emul HM, Ustundag B: High serum leptin levels in depressive disorders with atypical features. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005, 59 (6): 736-738.

Kluge M, Schussler P, Schmid D, Uhr M, Kleyer S, Yassouridis A, Steiger A: Ghrelin plasma levels are not altered in major depression. Neuropsychobiology. 2009, 59 (4): 199-204.

Schanze A, Reulbach U, Scheuchenzuber M, Groschl M, Kornhuber J, Kraus T: Ghrelin and eating disturbances in psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychobiology. 2008, 57 (3): 126-130.

Barim AO, Aydin S, Colak R, Dag E, Deniz O, Sahin I: Ghrelin, paraoxonase and arylesterase levels in depressive patients before and after citalopram treatment. Clin Biochem. 2009, 42 (10–11): 1076-1081.

Atmaca M, Tezcan E, Parmaksiz S, Saribas M, Ozler S, Ustundag B: Serum ghrelin and cholesterol values in suicide attempters. Neuropsychobiology. 2006, 54 (1): 59-63.

Pasco JA, Jacka FN, Williams LJ, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M: Leptin in depressed women: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from an epidemiologic study. J Affect Disord. 2008, 107 (1–3): 221-225.

Milaneschi Y, Simonsick EM, Vogelzangs N, Strotmeyer ES, Yaffe K, Harris TB, Tolea MI, Ferrucci L, Penninx BW: Leptin, abdominal obesity, and onset of depression in older men and women. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012, 73 (9): 1205-1211.

Nicklas BJ, Toth MJ, Goldberg AP, Poehlman ET: Racial differences in plasma leptin concentrations in obese postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997, 82 (1): 315-317.

Bacha F, Arslanian SA: Ghrelin and peptide YY in youth: are there race-related differences?. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91 (8): 3117-3122.

Akter S, Kurotani K, Nanri A, Pham NM, Sato M, Hayabuchi H, Mizoue T: Dairy consumption is associated with decreased insulin resistance among the Japanese. Nutr Res. 2013, 33 (4): 286-292.

Shima SST, Kitamura T, Asai M: New self-rating scale for depression (in Japanese). Jpn J Clin Psychiatry. 1985, 27: 717-723.

Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977, 1 (3): 385-401.

Wada K, Tanaka K, Theriault G, Satoh T, Mimura M, Miyaoka H, Aizawa Y: Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale as a screening instrument of major depressive disorder among Japanese workers. Am J Ind Med. 2007, 50 (1): 8-12.

Berk M, Sarris J, Coulson CE, Jacka FN: Lifestyle management of unipolar depression. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2013, 127: 38-54.

Bitew T: Prevalence and Risk Factors of Depression in Ethiopia: A Review. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014, 24 (2): 161-169.

Nanri A, Mizoue T, Matsushita Y, Sasaki S, Ohta M, Sato M, Mishima N: Serum folate and homocysteine and depressive symptoms among Japanese men and women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64 (3): 289-296.

Yi S, Nanri A, Poudel-Tandukar K, Nonaka D, Matsushita Y, Hori A, Mizoue T: Association between serum ferritin concentrations and depressive symptoms in Japanese municipal employees. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 189 (3): 368-372.

De Heredia FP, Gomez-Martinez S, Marcos A: Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012, 71 (2): 332-338.

Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Henry MJ, Kotowicz MA, Schneider HG, Leonard BE, Berk M: Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with de novo major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 197 (5): 372-377.

Shelton RC, Miller AH: Eating ourselves to death (and despair): the contribution of adiposity and inflammation to depression. Prog Neurobiol. 2010, 91 (4): 275-299.

Iwata N, Umesue M, Egashira K, Hiro H, Mizoue T, Mishima N, Nagata S: Can positive affect items be used to assess depressive disorders in the Japanese population?. Psychol Med. 1998, 28 (1): 153-158.

Lee S-A, Kallianpur A, Xiang Y-B, Wen W, Cai Q, Liu D, Fazio S, Linton MF, Zheng W, Shu XO: Intra-individual variation of plasma adipokine levels and utility of single measurement of these biomarkers in population-based studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16 (11): 2464-2470.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/203/prepub

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants for their cooperation and participation. We thank Seiko Miyazaki and Yasutaka Horiuchi (Kyushu University); Emi Tanaka, Youko Tsuruda, Misaki Hirose, Meishu Sai, Miho Isayama, Midori Sasaki, Mie Shimomura, and Azumi Uehara (Fukuka Women’s University); Yaeko Nagano (retired nurse), Akiko Hayashi, Yu Teruyama, Kae Saito, Kayoko Washizuka, and Yuho Mizoue (National Center for Global Health and Medicine) for their help in data collection. We also thank Kazuko Nagase and Dai Suzuki (Department of Metabolic Disorder, Diabetes Research Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine) for their contributions to measurements of serum adipokines.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (21390213) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (21790598) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. The funding bodies have no role in analysis and interpretation of data, in writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SA analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. NMP, AN, KK, FNJ and KK, contributed to data interpretation and discussion. KY contributed to measurement of leptin and ghrelin and discussion. MS contributed to discussion. JNF and TM extensively reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Akter, S., Pham, N.M., Nanri, A. et al. Association of serum leptin and ghrelin with depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 14, 203 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-203

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-203