Abstract

Background

The purpose of this article was to conduct a review of the types of training offered to people with schizophrenia in order to help them develop strategies to cope with or compensate for neurocognitive or sociocognitive deficits.

Methods

We conducted a search of the literature using keywords such as “schizophrenia”, “training”, and “cognition” with the most popular databases of peer-reviewed journals.

Results

We reviewed 99 controlled studies in total (though nine did not have a control condition). We found that drill and practice training is used more often to retrain neurocognitive deficits while drill and strategy training is used more frequently in the context of sociocognitive remediation.

Conclusions

Hypotheses are suggested to better understand those results and future research is recommended to compare drill and strategy with drill and practice training for both social and neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

About 80% of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia struggle with a variety of neurocognitive and sociocognitive deficits [1, 2]. The neurocognitive domains typically affected include speed of processing, attention/vigilance, working memory, verbal learning, reasoning and problem solving [3, 4], whereas social cue perception, affect recognition, attribution, and theory of mind are the sociocognitive domains most affected [5, 6]. Cognitive dysfunctions are considered to be core features of schizophrenia, since they are strongly correlated with poor functional outcome [7–9] as well as being better predictors of general outcome and rehabilitation than positive symptoms [10, 11]. Although pharmacological and psychological treatments can effectively reduce [12] positive symptoms of schizophrenia, they do little to improve cognition [7]. Thus, using cognitive retraining or remediation to create significant improvements has received more attention in recent years [7, 13]. According to T Wykes, V Huddy, C Cellard, SR McGurk and P Czobor [14], there are two types of training: 1) “drill and practice,” where there is no explicit component, meaning that learning is based on repeating a task that becomes gradually more difficult and where participants implicitly learn the strategy by trial and error, and 2) “drill and strategy,” where the focus is to teach the explicit use of a determined strategy (see also [12]). While explicit learning impairments have been consistently reported in schizophrenia literature [15, 16], there is still a debate over impairments to implicit learning. For example, some studies report that implicit learning is intact for tasks such as probabilistic classification learning (e.g., [17]), weather prediction (e.g., [18]), and artificial grammar learning (e.g., [19]), while others report an impairment in colour pattern learning but not in letter string learning [20]. Adding to this conundrum are a variety of different training procedures currently being tested, both for drill and strategy (includes explicit and implicit learning) and for drill and practice (implicit learning only). These training procedures focus on a variety of different targets therefore, in this review, we will focus on neurocognitive and sociocognitive domains. For this reason we will not include studies aiming solely to reduce positive or negative symptoms or to improve upon social skills. Contrary to the recently published meta-analyses focusing on efficacy of cognitive training [14, 21], this review will analyze and describe which training paradigms were most used to improve neurocognitive and sociocognitive deficits, whether they be drill and practice or drill and strategy methods.

Methods

Review protocol

Inclusion criteria: 1) outcome: either neurocognition or sociocognition, 2) date and journal: peer-reviewed journals from 1995 up to 2013, 3) language: English or French, 4) diagnosis: majority (≥70%) of participants with a schizophrenia diagnosis (others include schizoaffective disorders and first-episode psychosis). We excluded all training types that aimed solely to reduce positive or negative symptoms, improve social skills, increase metacognition, etc. Nevertheless, studies that targeted sociocognition or neurocognition while also aiming to reduce symptoms or improve social skills as secondary objective, were included. Finally, we removed studies that used the training or remediation for evaluation rather than for treatment (i.e., studies assessing the deficits at baseline with no intention of remediation or intervention) as well as meta-analyses and reviews. Our goal was to review studies that had a therapeutic outcome. Since the main objective of our article is to provide a descriptive listing of the training offered and not to conduct an efficacy analysis, we included studies that did not have control conditions. Given the large number of articles included (n = 99), and the fact that our definitions of the types of training were inclusive, the first three authors read, classified, and compared their ratings for each article to ensure reliability of the results. Articles were classified in two categories, according to the targeted deficits: i) Sociocognitive, which included topics such as emotional recognition, Theory of Mind, attributional style, and social cue recognition; ii) Neurocognitive, which included areas such as executive functioning, memory and attention. Importantly, social functioning was excluded from the dichotomy of classification as most, if not all studies, ultimately aim to improve upon work and functional outcomes of individuals. Furthermore, we compared the results of our literature search with articles listed in the meta-analyses of T Wykes, V Huddy, C Cellard, SR McGurk and P Czobor [14], O Grynszpan, S Perbal, A Pelissolo, P Fossati, R Jouvent, S Dubal and F Perez-Diaz [22] and A Medalia and AM Saperstein [23] to ensure that we did not miss any relevant articles.

Article retrieval

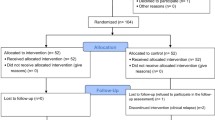

We conducted a literature review using the following databases: PsychINFO (1995 to May 2013), MEDLINE (R) (1995 to May 2013) and MEDLINE Daily Update (R). Using the title keywords “schizophrenia and (training or remediation or intervention or practice) and (soci*a or neuro* or cogniti* or metacogniti* or problem-solving or visual or memory)” , we obtained 465 results from all databases. To ensure further precision we added the following filters: a) “limit to English and French language” (to ensure understanding of the content) which yielded 172 results, b) “limit to peer-reviewed journals” resulting in 164 results. The final manipulation was to remove all duplicates, which left us with a total of 121 articles to investigate. Upon final removal of all articles that did not meet our criteria, we reviewed 99 articles. The last date of search for articles was January 2014.

Results

Results are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3, divided according to the aim of the studies: improving neurocognitive deficits, sociocognitive deficits or both. These were further subdivided by either drill and practice or drill and strategy training methods. First, we will describe the studies that focus on a single area of cognition (i.e., Table 1 for neurocognition and Table 2 for sociocognition) as treatment targets and that used a single training type (drill and practice or drill and strategy). Then, we will describe the results of studies with multiple aims in terms of neurocognitive and sociocognitive deficits (Table 3). There is an important distinction to be made between the targeted deficits – which is how we classified the studies between neurocognition, sociocognition, or both – and the measured variables. Indeed, it is often the case that a variable is measured to assess the impact of the training without having been specifically targeted by the training, which, therefore, gives a sense of the generalization of the results. As seen more explicitly in Table 2, many of the studies aiming to improve sociocognition also measure the impact of the training on more neurocognitive variables.

Neurocognitive deficits

We identified a total of 62 studies pertaining to neurocognitive training. Of these, 58 included randomized controlled trials or placebo conditions, while four had no control. At first glance (see Table 1), it appears that for people with schizophrenia drill and practice training is used more frequently to train neurocognitive deficits (i.e., drill and practice = 35 studies, 33 with controls and two without; drill and strategy = 27 studies, 25 with controls and two without).

Examining the drill and strategy studies, a pattern rapidly emerges when the methods of training are considered. Twelve of 27 studies used group therapy in their training rather than individual computerized training with therapist assistance. However, there does not seem to be a link between the method of training (individual or group) and the outcome measures. Though it is not the goal of our review, it is important to note that all articles with drill and strategy approaches to training reported between-group improvements of the targeted deficits. Furthermore, eight of the 17 studies with follow up measures at either three, four or six months also reported sustained gains in cognition [25, 32, 37, 41, 45, 47, 48, 50],[64].

Drill and practice studies most commonly used computerized tasks, done individually. However, there was more variety in the methods of training, for example, at least five studies used pencil-and-paper procedures [60, 67, 69, 73, 75]; though Lopez-Luengo utilized both pen-and-paper and audio] while five others used a combination of audio and visual tasks [62, 63, 77, 78, 83] to reduce the deficits. Furthermore, most studies using drill and practice methodologies (all except [61, 69]) reported between-group improvements in cognition between the experimental and control groups, at least for some measures.

The studies we analyzed targeted a variety of neurocognitive deficits - memory, attention/vigilance, reasoning, verbal learning - yet overall, across studies, no single deficit stood out as being resistant to implicit training. Therefore, it would seem that most domains of neurocognition respond well to drill and practice training, even though only seven studies had follow ups at six months, six [52, 55, 60, 63, 64, 82] confirming that the gains were maintained and one [65] showing that only the affect recognition benefits were not maintained at the 1-year follow up.

Sociocognitive deficits

In contrast to studies focusing on neurocognition, those aiming to improve sociocognitive deficits used mostly drill and strategy approaches (i.e., drill and practice = two studies with control groups; drill and strategy = 21 studies, 18 with controls and three without). Importantly, all studies included a variety of visual aids such as vignettes, Powerpoint presentations or videos of social situations. Furthermore, visual presentations and explanations by the therapist about the goal of the training were often done in group settings. This method allows modelling by the therapist but also incorporates group exercises and practice as well as role-plays.

Interestingly, for sociocognition, whether the training paradigm was drill and strategy (e.g. [97]) or drill and 210 practice (e.g. [107]), there was a general concern to assess whether remediation of a specific type of deficit would generate generalizable results, not only to functional outcomes but also to broader domains of social cognition such as Theory of Mind.

Studies that aimed to improve both neuro and sociocognition

It is more difficult to find a pattern in the types of training when the target deficits are broader and span across both neurocognitive (such as memory and attention) and sociocognitive domains (such as social perception and emotion recognition). However, most use drill and strategy paradigms that generally combine computer-assisted programs for neurocognition, and guided practice, modeling and role-play for sociocognition. There is also a mix of individualized and group approaches that seem, again, to follow the trend that neurocognition is trained individually while sociocognition is trained in groups, and this is true for both drill and practice as well as drill and strategy.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to review the type of training – whether drill and practice or drill and strategy – most often offered in clinical studies to people with schizophrenia to help overcome neurocognitive or sociocognitive deficits. We included articles with varying scientific value for both neurocognitive and sociocognitive training; nine of the 99 articles we reviewed had no control condition. However, since we are not presenting a thorough analysis of the efficacy or effectiveness of these training methods (see 14 for details, [22, 23]), we opted to include them for descriptive purposes. Although we found a variety of training modalities offered, some more behavioral, some using computer training, real-life situations, indirect training, etc., we were able to determine if a training paradigm was drill and practice or drill and strategy in nature, and which of these methods was used more frequently to improve neurocognitive or sociocognitive deficits. We also planned to describe the patterns and modalities used to train the targeted deficits (i.e., neuro- or sociocognitive).

In our literature search, we found that drill and practice training programs were used more frequently for improving neurocognitive deficits. Of the 62 studies we reviewed, 35 used procedures that mostly involved errorless learning, a type of training where the degree of difficulty of the task increases with the performance of the participant and where no conscious effort is necessary to improve. Studies using drill and strategy (n = 27) seemed particularly interested in the impact of the training on other variables outside of neurocognition, such as symptoms and quality of life. This was not the case for the drill and practice approaches. Another difference was that studies using drill and strategy training almost always measured executive functioning (n = 15), whereas studies using drill and practice training did not. However, we could not determine whether one specific domain of neurocognition was more easily retrained than another with drill and practice vs. drill and strategy procedures. Furthermore, most studies were of short duration and only a few had follow up measures (e.g., drill and strategy n = 8 [25, 32, 37, 41, 45, 47–49]; drill and practice n = 7 [52, 55, 60, 63–65, 82]. This could be improved upon in future studies, since it is difficult under these circumstances to decide whether the observed effects are maintained over time or not.

When attempting to put the findings on neurocognitive deficits into context, we wondered why drill and practice training would be used more often to retrain neurocognitive deficits. The answer may lie in the way these functions interact in our cognitive processes. Some domains, like attention and speed of information processing, seem more implicit by nature – the bottom-up approach. We could posit that these functions are not used consciously and a person would not need to inherently know “how” to use the functions; instead they would simply perform the task repetitively and unconsciously. However, this might imply that drill and practice procedures would only improve neurocognitive deficits, which might not be the case, as judged by the results reported in recent meta-analyses [14, 22]. Furthermore, since implicit learning has been reported as being generally intact in schizophrenia [84], some, like Fisher and colleagues [62], suggest that high levels of repetition (e.g., more than 1,000 rehearsals) and a high percentage of reward schedule (e.g.: 85%), will allow for neurological improvements. Yet, studies using drill and strategy procedures in their training methods also seem to generate consistent positive outcomes – the top-down approach. Of note, Wykes and colleagues [14] suggested that drill and strategy training include elements that are explicitly learned (through modeling, explanation or role-play – the “strategy”) but also elements inevitably linked with repetition (the “drill”) and considered implicit learning, which might explain why they are effective.

Tentatively, we suggest that since drill and strategy learning is thought to allow better integration of the rules and, thus, greater association between the various training elements [122], changes in cognition tend to occur over time. Blairy and colleagues [25], who also reported long-lasting improvements on memory and executive functions after explicit training, hypothesized that participants learned to bind different aspects of the experiment together and that it allowed for better consolidation in memory. Thus, at this time, we cannot draw a conclusion about whether certain domains of neurocognition respond better to one type of training over another. Further studies must be conducted, preferably comparing different forms of training with each other and adding follow up measures to assess whether the benefits of training remain stable through time.

Social cognition is considered by many researchers to have a strong relationship with positive functional outcomes [123, 124]. Concurrently, the meta-analysis by McGurk [12] reported that programs using strategy coaching (drill and strategy training) for sociocognitive deficits had strong effects on functional outcomes as well as on the targeted social cognition skills. Consistent with this, we found that drill and strategy training was more frequently used for sociocognitive retraining. It seems intuitive that learning and integrating a social skill requires that it be practiced in a social setting, which was consistent with our findings when analyzing the studies. Most used group settings, where participants received their training then performed and practiced the learned techniques with a therapist to correct the behavior and give feedback. Moreover, it was also reported that integrating rehearsals into the training yields greater functional outcome improvements [23]. Indeed, sociocognitive studies tend to measure social functioning or social adjustment following training more often than studies aiming to improve upon neurocognitive deficits. Yet, a growing field around implicit learning in social cognitive psychology [125] suggests that drill and practice or other forms of more implicit training might be useful for sociocognition as well.

The collection of studies of Bell and colleagues on work and social outcomes using drill and practice [53, 55] hint at the importance of generalizing the benefits of training to real-life situations, such as the ability to find and maintain work or to increase work productivity in the form of hours and money earned. However, both of these studies integrated the drill and strategy approach with a program of supported employment, creating a hybrid retraining program which has been efficient in the past [14]. Indeed, while improving cognitive deficits is commendable, functional outcomes are issues that should not be dismissed when considering the difficulties faced by individuals suffering from schizophrenia when trying to reintegrate the work force or create a social network.

We have also discovered that training programs usually target cognitive improvements “at large”, rather than specifically focusing on the individual deficits highlighted by the person’s profile, most likely to allow more people to receive the training without the need for specific neuropsychological or sociocognitive evaluations. We suggest choosing one type of training over another depending on the overall goal one is trying to achieve: drill and practice for precise deficits and drill and strategy to obtain general gains. More studies are needed to determine if drill and practice could be useful for sociocognition as well.

Furthermore, specific training methodologies seem to benefit specific domains of social cognition. For example, though it appears that Social Cognition and Interaction Training (even when including the family in the training sessions) improves Theory of Mind (ToM), group practices and Powerpoint presentations detailing the concepts of ToM did not improve ToM but did improve emotion recognition. We suggest that ToM is a more complex construct of sociocognition and requires more precise and detailed training than emotion recognition. Horan and colleagues [93] suggest that even defining the different concepts contained within ToM, such as appreciation of humour, is difficult and the training for it is more challenging. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of social cognition training in schizophrenia [21] also reported inconsistent effect sizes when ToM is targeted, suggesting that the key elements needed in the training for ToM must be better identified.

When the objectives of the training are broader, meaning that they aim to improve both neurocognitive and sociocognitive deficits through drill and strategy, the variables measured are also more varied and often include certain measures of functional or occupational outcome. Furthermore, these studies often tend to combine training with other types of intervention such as cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive therapy or occupational therapy.

Overall, our review summarizes the current state of research into cognitive training in schizophrenia. In neurocognition, drill and practice training is used more frequently and with a variety of different procedures such as auditory training [62] or target discrimination [74]. Tailoring the training to specifically address precise deficits might be one of the key benefits of drill and practice training. However, from the studies we evaluated, drill and strategy training was more easily generalized to all neurocognitive deficits. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis on the benefits of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia noted that this modality of training produces stable benefits on global cognition [14]. We suggest choosing one type of training over another depending on the overall goal one is trying to achieve: drill and practice for precise deficits and drill and strategy to obtain general gains in neurocognition.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to our review. First, to reflect current trends, we included only studies published between 1995 and 2013, although interest in cognition remediation started as early as the end of the 1970’s [126]. Second, the fact that drill and practice or drill and strategy training can involve multiple strategies and training techniques (e.g., times eye tracking, computer programs, paper-pencil tasks, errorless learning, group learning, and various modalities of feedback) prevented us from describing them in detail and some of these specific strategies might explain differences in outcomes. Our goal was to describe what was being offered, not to promote one approach in particular. We also did not include studies described as “metacognitive”, a term that involves cognitive biases, at times social and/or neurocognitive, that are linked to the symptoms of psychosis [127] – for example, focusing on the cognitive bias of jumping to conclusions as linked to delusions. It is important to note that these types of training are not the only modalities offered to help overcome neurocognitive or sociocognitive deficits. Occupational therapy [128], social skills training [129], as well as certain forms of metacognitive psychotherapies [130] have also been documented.

Conclusion

Future research is warranted to compare both drill and strategy and drill and practice programs with one another under control and experimental conditions, as well as to highlight the benefits and limitations of each. This would help to identify which type of deficit would benefit more from which training or to isolate particular participant profiles that respond best to a specific training strategy. Moreover, we suggest that more focus be brought to targeting participants’ specific deficits to tailor the training to those needs. This would increase the potential impact and generalization to “real-life” situations, both in the context of neuro and sociocognitive retraining. Finally, we propose investigating the benefits of both neurocognitive and sociocognitive training in the context of comorbidity. It is well know that schizophrenia is often comorbid with social anxiety (in 30% of cases; [131]) and substance abuse (in 50% of cases; [132]), to name a few. It is conceivable that the interplay of those disorders could be a substantial challenge for training. Nevertheless, very few studies have examined the impact of these presentations and doing so would be of paramount importance as it could increase the ecological validity and generalizability of the results.

Endnote

a*stands for truncation.

References

Meesters PD, Stek ML, Comijs HC, de Haan L, Patterson TL, Eikelenboom P, Beekman ATF: Social functioning among older community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia: a review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010, 18 (10): 862-878. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e446ff.

Raffard S, Gely-Nargeot MC, Capdevielle D, Bayard S, Boulenger JP: Learning potential and cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Encéphale. 2009, 35 (4): 353-360.

Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD: The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165 (2): 203-213. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042.

Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D: The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res. 2013, 150 (1): 42-50. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.009.

Lecardeur L, Stip E, Giguere M, Blouin G, Rodriguez J-P, Champagne-Lavau M: Effects of cognitive remediation therapies on psychotic symptoms and cognitive complaints in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a randomized study. Schizophr Res. 2009, 111 (1–3): 153-158.

Wolwer W, Frommann N: Social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: generalization of effects of the Training of Affect Recognition (TAR). Schizophr Bull. 2011, 37 (Suppl 2): S63-S70. 10.1093/schbul/sbr071.

Keefe RS, Vinogradov S, Medalia A, Silverstein SM, Bell MD, Dickinson D, Ventura J, Marder SR, Stroup T: Report from the working group conference on multisite trial design for cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011, 37 (Suppl 5): 1057-1065.

Kurtz M, Seltzer J, Shagan D, Thime W, Wexler B: Computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: what is the active ingredient?. Schizophr Res. 2007, 89 (1–3): 251-260.

Revheim N, Schechter I, Kim D, Silipo G, Allingham B, Butler P, Javitt DC: Neurocognitive and symptom correlates of daily problem-solving skills in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006, 83 (2–3): 237-245.

Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia?. Am J Psychiatry. 1996, 153 (3): 321-330.

Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS: Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 36 (1): 316-338. 10.1038/npp.2010.156.

McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT: A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007, 164 (12): 1791-1802. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906.

Franck N: Cognitive remediation for patients with schizophrenia. Ann Medico-Psychol. 2007, 165 (3): 187-190. 10.1016/j.amp.2007.01.006.

Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P: A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011, 168 (5): 472-485. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855.

Aleman A, Hijman R, de Haanm EHF, Kahn RS: Memory impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999, 256: 1358-1366.

Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK: Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychol. 1998, 12: 426-445.

Keri S, Kelemen O, Szekeres G, Bagoczky N, Erdelyi R, Antal A, Benedek G, Janka Z: Schizophrenics know more than they can tell: probabilistic classification learning in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2000, 30 (1): 149-155. 10.1017/S0033291799001403.

Weickert TW, Terrazas A, Bigelow LB, Malley JD, Hyde T, Egan MF, Weinberger DR, Goldberg TE: Habit and skill learning in schizophrenia: evidence of normal striatal processing with abnormal cortical input. Learn Mem. 2002, 9 (6): 430-442. 10.1101/lm.49102.

Danion JM, Meulemans T, Kauffmann-Muller F, Vermaat H: Intact implicit learning in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158 (6): 944-948. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.944.

Hsieh MH, Liu K, Liu S-K, Chiu M-J, Hwu H-G, Chen ACN: Memory impairment and auditory evoked potential gating deficit in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 130 (2): 161-169. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2002.12.001.

Kurtz M, Richardson CL: Social cognitive training for schizophrenia: a meta-analytic investigation of controlled research. Schizoph Bull. 2011, 38 (5): 1092-1104.

Grynszpan O, Perbal S, Pelissolo A, Fossati P, Jouvent R, Dubal S, Perez-Diaz F: Efficacy and specificity of computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: a meta-analytical study. Psychol Med. 2011, 41 (1): 163-173. 10.1017/S0033291710000607.

Medalia A, Saperstein AM: Does cognitive remediation for schizophrenia improve functional outcomes?. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013, 26: 151-157. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835dcbd4.

Bark N, Revheim N, Huq F, Khalderov V, Ganz ZW, Medalia A: The impact of cognitive remediation on psychiatric symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2003, 63: 229-235. 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00374-2.

Blairy S, Neumann A, Nutthals F, Pierret L, Collet D, Philippot P: Improvements in autobiographical memory of schizophrenia patients after a cognitive intervention: a preliminary study. Psychopathol. 2008, 41 (6): 388-396. 10.1159/000155217.

Bowie CR, McGurk SR, Mausbach B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD: Combined cognitive remediation and functional skills training for schizophrenia: effects on cognition, functional competence, and real-world behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2012, 169 (7): 710-718.

Bowie CR, Grossman M, Gupta M, Oyewumi LK, Harvey PD: Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: Efficacy and effectiveness in patients with early versus long-term course of illness. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013, 8 (1): 32-38.

Dickinson D, Tenhula W, Morris S, Brown C, Peer J, Spencer K, Li L, Gold JM, Bellack AS: A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010, 167 (2): 170-180. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020264.

Fiszdon JM, Whelahan H, Bryson GJ, Wexler BE, Bell MD: Cognitive training of verbal memory using a dichotic listening paradigm: impact on symptoms and cognition. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005, 112: 187-193. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00565.x.

Gharaeipour M, Scott BJ: Effects of cognitive remediation on neurocognitive functions and psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia inpatients. Schizoph Res. 2012, 142: 165-170. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.018.

Hansen JP, Ostergaard B, Nordentoft M, Hounsgaard L: The feasibility of cognitive adaptation training for outpatients with schizophrenia in integrated treatment. Community Ment Health J. 2012, 1-6.

Hodge MAR, Siciliano D, Withey P, Moss B, Moore G, Judd G, Shores EA, Harris A: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 2010, 36 (2): 419-427. 10.1093/schbul/sbn102.

Ikezawa S, Mogami T, Hayami Y, Sato I, Kato T, Kimura I, Pu S, Kaneko K, Nakagome K: The pilot study of a neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation for patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 195 (3): 107-110. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.020.

Kern RS, Liberman RP, Becker DR, Drake RE, Sugar CA, Green MF: Errorless learning for training individuals with schizophrenia at a community mental health setting providing work experience. Schizoph Bull. 2009, 35 (4): 807-815. 10.1093/schbul/sbn010.

Kidd SA, Bajwa JK, McKenzie KJ, Ganguli R, Khamneh BH: Cognitive remediation for individuals with psychosis in a supported education setting: a pilot study. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012, 2012 (715176): 5-

McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A: Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizoph Bull. 2005, 31 (4): 898-909. 10.1093/schbul/sbi037.

McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A: Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007, 164 (3): 437-441. 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.437.

Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: The remediation of problem-solving skills in schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 2001, 27 (2): 259-267. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006872.

Penades R, Boget T, Catalan R, Bernardo M, Gasto C, Salamero M: Cognitive mechanisms, psychosocial functioning, and neurocognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2003, 63 (3): 219-227. 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00359-6.

Penades R, Catalan R, Salamero M, Boget T, Puig O, Guarch J, Gasto C: Cognitive remediation therapy for outpatients with chronic schizophrenia: a controlled and randomized study. Schizoph Res. 2006, 87: 323-331. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.019.

Poletti S, Anselmetti S, Bechi M, Ermoli E, Bosia M, Smeraldi E, Cavallaro R: Computer-aided neurocognitive remediation in schizophrenia: durability of rehabilitation outcomes in a follow-up study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010, 20 (5): 659-674. 10.1080/09602011003683158.

Royer A, Grosselin A, Bellot C, Pellet J, Billard S, Lang F, Brouillet D, Massoubre C: Is there any impact of cognitive remediation on an ecological test in schizophrenia?. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2012, 17 (1): 19-35. 10.1080/13546805.2011.564512.

Silverstein SM, Hatashita-Wong M, Solak BA, Uhlhaas P, Landa Y, Wilkniss SM, Goicochea C, Carpiniello K, Schenkel LS, Savitz A, Smith TE: Effectiveness of a two-phase cognitive rehabilitation intervention for severely impaired schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2005, 35 (6): 829-837. 10.1017/S0033291704003356.

Spaulding WD, Reed D, Sullivan M, Richardson C, Weiler M: Effects of cognitive treatment in psychiatric rehabilitation. Schizoph Bull. 1999, 25 (4): 657-676. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033409.

Twamley EW, Savla GN, Zurhellen CH, Heaton RK, Jeste DV: Development and pilot testing of a novel compensatory cognitive training intervention for people with psychosis. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008, 11 (2): 144-163.

Vauth R, Corrigan PW, Clauss M, Dietl M, Dreher-Rudolph M, Stieglitz R-D, Vater R: Cognitive strategies versus self-management skills as adjunct to vocational rehabilitation. Schizoph Bull. 2005, 31 (1): 55-66. 10.1093/schbul/sbi013.

Wykes T, Reeder C, Corner J, Williams C, Everitt B: The effects of neurocognitive remediation on executive processing in patients with schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 1999, 25 (2): 291-307. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033379.

Wykes T, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J, Rice C, Everitt B: Are the effects of cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) durable? Results from an exploratory trial in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2003, 61: 163-174. 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00239-6.

Wykes T, Reeder C, Landau S, Everitt B, Knapp M, Patel A, Romeo R: Cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007, 190: 421-427. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026575.

Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, Rice C, Thompson N, Frangou S: Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizoph Res. 2007, 94 (1–3): 221-230.

Bell M, Bryson G, Greig TC, Corcoran C, Wexler B: Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with work therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001, 58: 763-768. 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.763.

Bell M, Bryson G, Wexler BE: Cognitive remediation of working memory deficits: durability of training effects in severely impaired and less severely impaired schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003, 108 (2): 101-109. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00090.x.

Bell M, Bryson G, Greig TC, Fiszdon JM, Wexler B: Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with work therapy: productivity outcomes at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005, 42 (6): 829-838. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.03.0061.

Bell M, Fiszdon JM, Greig TC, Wexler B, Bryson G: Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with work therapy in schizophrenia: 6-month follow-up of neuropsychological performance. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007, 44 (5): 761-770. 10.1682/JRRD.2007.02.0032.

Bell MD, Zito W, Greig TC, Wexler B: Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with vocational services: work outcomes at two-year follow-up. Schizoph Res. 2008, 105: 18-29. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.026.

Belluci DM, Glaberman K, Haslam N: Computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation reduces negative symptoms in the severely mentally ill. Schizophr Res. 2002, 59: 225-232.

Chan CL, Ngai EK, Leung PK, Wong S: Effect of the adapted virtual reality cognitive training program among Chinese older adults with chronic schizophrenia: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 25 (6): 643-649.

d’Amato T, Bation R, Cochet A, Jalenques I, Galland F, Giraud-Baro E, Pacaud-Troncin M, Augier-Astolfi F, Llorca P-M, Saoud M, Brunelin J: A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2011, 125 (2–3): 284-290.

D’Souza DC, Radhakrishnan R, Perry E, Bhakta S, Singh NM, Yadav R, Abi-Saab D, Pittman B, Chaturvedi SK, Sharma MP, Bell M, Andrada C: Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of the combination of d-serine and computerized cognitive retraining in schizophrenia: an International Collaborative Pilot Study. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 1-12.

Farreny A, Aguado J, Ochoa S, Huerta-Ramos E, Marsa F, Lopez-Carrilero R, Carral V, Haro JM, Usall J: REPYFLEC cognitive remediation group training in schizophrenai. Looking for an integrative approach. Schizoph Res. 2012, 142: 137-144. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.035.

Field CD, Galletly C, Anderson D, Walker P: Computer-aided cognitive rehabilitation: possible application to the attentional deficit of schizophrenia, a report of negative results. Percept Mot Skills. 1997, 85: 995-1002. 10.2466/pms.1997.85.3.995.

Fisher M, Holland C, Merzenich MM, Vinogradov S: Using neuroplasticity-based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009, 166 (7): 805-811. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08050757.

Fisher M, Holland C, Subramaniam K, Vinogradov S: Neuroplasticity-based cognitive training in schizophrenia: an interim report on the effects 6 months later. Schizoph Bull. 2010, 36 (4): 869-879. 10.1093/schbul/sbn170.

Fiszdon JM, Bryson GJ, Wexler BE, Bell MD: Durability of cognitive remediation training in schizophrenia: performance on two memory tasks at 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 125 (1): 1-7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.10.004.

Greig TC, Zito W, Wexler BE, Fiszdon J, Bell MD: Improved cognitive function in schizophrenia after one year of cognitive training and vocational services. Schizoph Res. 2007, 96 (1–3): 156-161.

Habel U, Koch K, Kellerman T, Reske M, Frommann N, Wolwer W, Zilles K, Shah NJ, Schneider F: Training of affect recognition in schizophrenia: neurobiological correlates. Soc Neurosci. 2010, 5 (1): 92-104. 10.1080/17470910903170269.

Kontis D, Huddy V, Reeder C, Landau S, Wykes T: Effects of age and cognitive reserve on cognitive remediation therapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013, 21 (3): 218-230. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.013.

Lindenmayer J-P, McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Khan A, Wance D, Hoffman L, Wolfe R, Xie H: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation among inpatients with persistent mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2008, 59 (3): 241-247. 10.1176/appi.ps.59.3.241.

Lopez-Luengo B, Vazquez C: Effects of attention process training on cognitive functioning of schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 119: 41-53. 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00102-1.

Medalia A, Aluma M, Tryon W, Merriam AE: Effectiveness of attention training in schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 1998, 24 (1): 147-152. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033306.

Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: Remediation of memory disoders in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2000, 30: 1451-1459. 10.1017/S0033291799002913.

Murthy NV, Mahncke H, Wexler BE, Maruff P, Inamdar A, Zucchetto M, Lund J, Shabbir S, Shergill S, Keshavan M, Kapur S, Laruelle M, Alexander R: Computerized cognitive remediation training for schizophrenia: an open label, multi-site, multinational methodology study. Schizoph Res. 2012, 139: 87-91. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.042.

Nemoto T, Yamazawa R, Kobayashi H, Fujita N, Chino B, Fujii C, Kashima H, Rassovsky Y, Green MF, Mizuno M: Cognitive training for divergent thinking in schizophrenia: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009, 33 (8): 1533-1536. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.08.015.

Norton DJ, McBain RK, Ongur D, Chen Y: Perceptual training strongly improves visual motion perception in schizophrenia. Brain Cogn. 2011, 77: 248-256. 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.08.003.

Penades R, Pujol N, Catalan R, Massana G, Rametti G, Garcia-Rizo C, Bargallo N, Gasto C, Bernardo M, Junque C: Brain effects of cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: a structural and functional neuroimaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013, 73: 1015-1023. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.017.

Popov T, Jordanov T, Rockstroch B, Elbert T, Merzenich MM, Miller GA: Specific cognitive training normalizes auditory sensory gating in schizophrenia: a randomized trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 69: 465-471. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.028.

Popov T, Rockstroch B, Weisz N, Elbert T, Miller GA: Adjusting brain dynamics in schizophrenia by means of perceptual and cognitive training. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (7): e39051-10.1371/journal.pone.0039051.

Rass O, Forsyth JK, Bolbecker AR, Hetrick WP, Breier A, Lysaker PH, O’Donnell BF: Computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: a randomized single-blind pilot study. Schizoph Res. 2012, 139 (1–3): 92-98.

Rauchensteiner S, Kawohl W, Ozgurdal S, Littmann E, Gudlowski Y, Witthaus H, Heinz A, Juckel G: Test-performance after cognitive training in persons at risk mental state of schizophrenia and patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 185: 334-339. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.003.

Rodewald K, Rentrop M, Holt DV, Roesch-Ely D, Backenstras M, Funke J, Weisbrod M, Kaiser S: Planning and problem-solving training for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2011, 11: 73-10.1186/1471-244X-11-73.

Sartory G, Zorn C, Groetzinger G, Windgassen K: Computerized cognitive remediation improves verbal learning and processing speed in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2005, 75 (2–3): 219-223.

Subramaniam K, Luks TL, Fisher M, Simpson GV, Nagarajan S, Vinogradov S: Computerized cognitive training restores neural activity within the reality monitoring network in schizophrenia. Neuron. 2012, 73: 842-853. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.024.

Surti TS, Corbera S, Bell MD, Wexler BE: Successful computer-based visual training specifically predicts visual memory enhancement over verbal memory improvement in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2011, 132 (2–3): 131-134.

Wexler BE, Hawkins KA, Rounsaville B, Anderson M, Sernyak MJ, Green MF: Normal neurocognitive performance after extended practice in patients with schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 1997, 26 (2–3): 173-180.

Choi K-H, Kwon J-H: Social cognition enhancement training for schizophrenia: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J. 2006, 42 (2): 177-187. 10.1007/s10597-005-9023-6.

Combs D, Adams SD, Penn DL, Roberts D, Tiegreen J, Stem P: Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for inpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: preliminary findings. Schizoph Res. 2007, 91: 112-116. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.010.

Combs D, Elerson K, Penn DL, Tiegreen JA, Nelson A, Ledet SN, Basso MR: Stability and generalization of Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) for schizophrenia: six-month follow-up results. Schizoph Res. 2009, 112 (1–3): 196-197.

Corrigan PW, Hirschbeck JN, Wolfe M: Memory and vigilance training to improve social perception in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 1995, 17 (3): 257-265. 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00008-9.

Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan M: Cognitive enhancement therapy improves emotional intelligence in early course schizophrenia: preliminary effects. Schizoph Res. 2007, 89: 308-311. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.018.

Fuentes I, Garcia S, Ruiz JC, Soler M, Roder V: Social perception training in schizophrenia: a pilot study. Int J Psychol. 2007, 7 (1): 1-12.

Garcia S, Fuentes I, Ruiz JC, Gallach E, Roder V: Application of the IPT in a Spanish sample: evaluation of the “social perception subprogramme”. Int J Psychol. 2003, 3 (2): 299-310.

Hodel B, Kern RS, Brenner HD: Emotion Management Training (EMT) in persons with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: First results. Schizoph Res. 2004, 68: 107-108. 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00119-1.

Horan W, Kern RS, Shokat-Fadai K, Sergi MJ, Wynn JK, Green MF: Social cognitive skills training in schizophrenia: an initial efficacy study of stabilized outpatients. Schizoph Res. 2009, 107 (1): 47-54. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.006.

Horan WP, Kern RS, Tripp C, Hellemann G, Wynn JK, Bell M, Marder SR, Green MF: Efficacy and specificity of social cognitive skills training for outpatients with psychotic disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2011, 45: 1113-1122. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.01.015.

Kayser N, Sarfati Y, Besche C, Hardy-Bayle M-C: Elaboration of a rehabilitation method based on a pathogenetic hypothesis of “theory of mind” impairment in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2006, 16 (1): 83-95. 10.1080/09602010443000236.

Lindenmayer J-P, McGurk SR, Khan A, Kaushik S, Thanju A, Hoffman L, Valdez G, Wance D, Herrman E: Improving social cognition in schizophrenia: a pilot intervention combining computerized social cognition training with cognitive remediation. Schizoph Bull. 2012, 39 (3): 507-517.

Mazza M, Lucci G, Pacitti F, Pino MC, Mariano M, Casacchia M, Roncone R: Could schizophrenic subjects improve their social cognition abilities only with observation and imitation of social situations?. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010, 20 (5): 675-703. 10.1080/09602011.2010.486284.

Marsh P, Langdon R, McGuire J, Harris A, Polito V, Coltheart M: An open clinical trial assessing a novel training program for social cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Australas Psychiatry. 2013, 21 (2): 122-126. 10.1177/1039856213475683.

Penn D, Roberts D, Combs D, Sterne A: The development of the social cognition and interaction training program for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Serv. 2007, 58 (4): 449-451. 10.1176/appi.ps.58.4.449.

Roberts DL, Penn DL: Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for outpatients with schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 166 (2–3): 141-147.

Russell TA, Green MJ, Simpson I, Coltheart M: Remediation of facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: concomitant changes in visual attention. Schizoph Res. 2008, 103 (1–3): 248-256.

Sanz DG, Lorenzo MD, Seco RB, Rodriguez MA, Martinez IL, Calleja RS, Soltero AA: Efficacy of a social cognition training program for schizophrenic patients: a pilot study. Span J Psychol. 2009, 12 (1): 184-191. 10.1017/S1138741600001591.

Silver H, Goodman C, Knoll G, Isakov V: Brief emotion training improves recognition of facial emotions in chronic schizophrenia. A pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2004, 128: 147-154. 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.002.

Tas C, Danaci AE, Cubukcuoglu Z, Brune M: Impact of family involvement on social cognition training in clinically stable outpatients with schizophrenia - A randomized pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 195 (1–2): 32-38.

van der Gaag M, Kern RS, van den Bosch RJ, Liberman RP: A controlled trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 2002, 28 (1): 167-176. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006919.

Wolwer W, Frommann N, Halfmann S, Piaszek A, Streit M, Gaebel W: Remediation of impairments in facial affect recognition in schizophrenia: efficacy and specificity of a new training program. Schizoph Res. 2005, 80: 295-303. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.018.

Wolwer W, Frommann N: Social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: generalization of effects of the training of affect recognition (TAR). Schizoph Bull. 2011, 37 (2): 63-70.

Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS: Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Serv. 2009, 60 (11): 1468-1476.

Galderisi S, Piegari G, Mucci A, Acerra A, Luciano L, Rabasca AF, Santucci F, Valente A, Volpe M, Mastantuono P, Maj M: Social skills and neurocognitive individualized training in schizophrenia: comparison with structured leisure activities. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010, 260 (4): 305-315. 10.1007/s00406-009-0078-1.

Hadas-Lidor N, Katz N, Tyano S, Weizman A: Effectiveness of dynamic cognitive intervention in rehabilitation of clients with schizophrenia. Clin Rehabil. 2001, 15 (4): 349-359. 10.1191/026921501678310153.

Hogarty SS, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald DP, Pogue-Geile M, Kechavan M, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Garrett A, Parepally H, Zoretich R: Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004, 61: 866-876. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.866.

Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Eack SM: Durability and mechanism of effects of cognitive enhancement therapy. Psychiatric Serv. 2006, 57 (12): 1751-1757. 10.1176/appi.ps.57.12.1751.

Lewandowski KE, Eack SM, Hogarty SS, Greenwald DP, Keshavan M: Is cognitive enhancement therapy equally effective for patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder?. Schizoph Res. 2011, 125: 291-294. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.017.

Sacks S, Fisher M, Garrett C, Alexander P, Holland C, Rose D, Hooker C, Vinogradov S: Combining computerized social cognitive training with neuroplasticity-based auditory training in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2013, 73: 935-937.

Ueland T, Rund BR: A controlled randomized treatment study: the effects of a cognitive remediation program on adolescents with early onset psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004, 109: 70-74. 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00239.x.

Ueland T, Rund BR: Cognitive remediation for adolescents with early onset psychosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005, 111: 193-201. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00503.x.

Veltro F, Mazza M, Vendittelli N, Alberti M, Casacchia M, Roncone R: A comparison of the effectiveness of problem solving training and of cognitive-emotional rehabilitation on neurocognition, social cognition and social functioning in people with schizophrenia. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011, 7: 123-132. 10.2174/1745017901107010123.

Vita A, De Peri L, Barlati S, Cacciani P, Cisima M, Deste G, Cesana BM, Sacchetti E: Psychopathologic, neuropsychological and functional outcome measures during cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia: a prospective controlled study in a real-world setting. Eur Psychiatry. 2011, 26: 276-283.

Vita A, De Peri L, Barlati S, Cacciani P, Deste G, Poli R, Agrimi E, Cesana BM, Sacchetti E: Effectiveness of different modalities of cognitive remediation on symptomatological, neuropsychological, and functional outcome domaines in schizophrenia: a prospective study in a real-world setting. Schizoph Res. 2011, 133: 223-231. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.08.010.

Cavallaro R, Anselmetti S, Poletti S, Bechi M, Ermoli E, Cocchi F, Stratta P, Vita A, Rossi A, Smeraldi E: Computer-aided neurocognitive remediation as an enhancing strategy for schizophrenia rehabilitation. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 169 (3): 191-196. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.027.

Hooker CI, Bruce L, Fisher M, Verosky SC, Miyakawa A, Vinogradov S: Neural activity during emotion recognition after combined cognitive plus social cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2012, 139: 53-59. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.009.

Yang J, Li P: Brain networks of explicit and implicit learning. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (8): e42993-10.1371/journal.pone.0042993.

Penn DL, Mueser KT, Doonan R, Nishith P: Relations between social skills and ward behavior in chronic schizophrenia. J Schizoph Res. 1995, 16: 225-232. 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00084-L.

Pinkham AE, Penn DL: Neurocognitive and social cognitive predictors of interpersonal skill in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2006, 143: 167-178. 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.005.

Gawronski B, Payne BK: Handbook of implicit social social cognition: measurement, theory, and applications. 2010, New York: Guilfort Press, 80-95.

Cromwell RL: Assessment or schizophrenia. Annu Rev Psychol. 1975, 26: 593-619. 10.1146/annurev.ps.26.020175.003113.

Moritz S, Veckenstedt R, Randjbar S, Vitzthum F, Woodward T: Antipsychotic treatment beyond antipsychotics: metacognitive intervention for schizophrenia patients improves delusional symptoms. Psychol Med. 2011, 41 (9): 1823-1832. 10.1017/S0033291710002618.

Cook S, Chambers E, Coleman JH: Occupational therapy for people with psychotic conditions in community settings: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2009, 23 (1): 40-52. 10.1177/0269215508098898.

Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R: Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 2006, 32 (Suppl 1): S12-S23.

Lysaker PH, Erickson M, Ringer J, Buck KD, Semerari A, Carcione A, Dimaggio G: Metacognition in schizophrenia: the relationship of mastery to coping, insight, self-esteem, social anxiety, and various facets of neurocognition. Br J Clin Psychol. 2011, 50 (4): 412-424. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2010.02003.x.

Kingsep P, Nathan P, Castle D: Cognitive behavioural group treatment for social anxiety in schizophrenia. Schizoph Res. 2003, 63: 121-129. 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00376-6.

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. J Am Med Assoc. 1990, 264: 2511-2518. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/139/prepub

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the research coordinator from our laboratory Ms. Melanie Lepage, for her invaluable help concerning the search of the various databases to retrieval our article. Further thanks to Dr. Caroline Cellard, for agreeing to jump in at the last minute, to help us improve the integrity and precision of our work.

Funding

This systematic and descriptive review was not funded by any research grants or funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KP conducted the literature search, selected and classified the appropriate articles, created the tables and wrote the manuscript.ALW read and classified the review articles to double-check KP’s previous work. She was also the first reader of some articles, in which case KP double-checked the classification. CC reviewed the comments from the reviewers and suggested improvements for the manuscript while answering the reviewers concerns. She also read and reviewed some articles that were missing from the first version of the manuscript. TL and SP are KP’s thesis director and co-director, respectively. They provided proof-reading, editing suggestions and feedback on the writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Paquin, K., Wilson, A.L., Cellard, C. et al. A systematic review on improving cognition in schizophrenia: which is the more commonly used type of training, practice or strategy learning?. BMC Psychiatry 14, 139 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-139

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-139