Abstract

Background

Individuals with serious mental illness are at a higher risk of physical ill health. Mortality rates are at least twice those of the general population with higher levels of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, diabetes, and respiratory illness. Although genetics may have a role in the physical health problems of these patients, lifestyle and environmental factors such as levels of smoking, obesity, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity also play a prominent part.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing the effect of exercise interventions on individuals with serious mental illness.

Searches were made in Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Biological Abstracts on Ovid, and The Cochrane Library (January 2009, repeated January 2013) through to February 2013.

Results

Eight RCTs were identified in the systematic search. Six compared exercise versus usual care. One study assessed the effect of a cycling programme versus muscle strengthening and toning exercises. The final study compared the effect of adding specific exercise advice and motivational skills to a simple walking programme. The review found that exercise improved levels of exercise activity (n = 13, standard mean difference [SMD] 1.81, CI 0.44 to 3.18, p = 0.01). No beneficial effect was found on negative (n = 84, SMD = -0.54, CI -1.79 to 0.71, p = 0.40) or positive symptoms of schizophrenia (n = 84, SMD = -1.66, CI -3.78 to 0.45, p = 0.12). No change was found on body mass index compared with usual care (n = 151, SMD = -0.24, CI -0.56 to 0.08, p = 0.14), or body weight (n = 77, SMD = 0.13, CI -0.32 to 0.58, p = 0.57). No beneficial effect was found on anxiety and depressive symptoms (n = 94, SMD = -0.26, CI -0.91 to 0.39, p = 0.43), or quality of life in respect of physical and mental domains.

Conclusions

This systematic review showed that exercise therapies can lead to a modest increase in levels of exercise activity but overall there was no noticeable change for symptoms of mental health, body mass index, and body weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is now a greater focus on patients’ physical health by mental health services [1]. People with serious mental illness have consistently higher levels of mortality and morbidity than the general population. Mortality rates remain persistently high around twice those of the general population [2]. The life expectancy of people with serious mental illness is shortened by between 11 and 18 years [3]. Despite a steady reduction in mortality rates in the general population no significant change has been observed in people with serious mental illness [4]. The widening differential gap in mortality suggests that people with schizophrenia have not fully benefited from the improvements in health outcomes available to the non-mentally ill population [2].

The underlying causes for the health problems of this population are both complex and multi-factorial [5]. People with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia have higher levels of cardiovascular disease [6, 7], metabolic disease [8], diabetes [9, 10], and respiratory illness [11, 12]. Although genetics may have a role in the physical health problems of these patients, lifestyle and environmental factors such as smoking, obesity, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity play a prominent part [13]. Some of the treatments given to people with serious mental illness contribute to the health problems in this population. For example, neuroleptic medication can lead to significant metabolic problems such as weight gain, lipid abnormalities, and changes in glucose regulation [14]. Evidence is becoming clearer that long term exposure to these medications may contribute to the higher mortality levels in this population [5].

There is now a greater focus on attempting to improve the physical health of these patients. However they have less access to medical care, poorer quality of care, and preventative health checks are less commonly completed in both primary and secondary care compared with the general population [15–17]. The nature of their mental illness may also affect their motivation as many individuals may be not ready to change their lifestyle [18, 19]. Individuals with serious mental illness have higher levels of smoking, weight problems, poor dietary intake, and low levels of physical activity. Rates of smoking of up to 70% have been found in patients with schizophrenia [7, 20, 21]. The prevalence of smoking in the general population is approximately 20% [22]. Individuals with serious mental illness have a poorer diet than the non-mentally ill population [20, 23]. Levels of obesity range from 40-60%, up to four times that of the non-mentally ill population [24–26]. These individuals are less active with lower levels of physical activity compared with the general population [27–29].

Regular physical activity has been found to be beneficial for both physical and mental health in the general population. There is a direct relationship between physical activity and a reduction in cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, and hypertension [30, 31]. Physical activity also leads to a reduction in the risk of metabolic health problems such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome [30]. A routine level of at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week is required to achieve a consistent reduction in risk [31]. In the general population about 60% of men and 70% of women self-report less than the recommended levels and objective measures of activity suggest that far more of these individuals are failing to meet the recommendations [32]. Physical activity has beneficial effects on mental health. It has been shown to be effective in the treatment of depression [33] and anxiety disorders [34]. It has positive effects on psychological well-being [35], quality of life [36] and in the reduction of stress [37].

The aim of this review was to determine the effectiveness of exercise programmes for people with serious mental illness. Two main objectives of this review were to firstly determine the effect of these programmes on levels of exercise activity, and secondly the effect of exercise on mental health and well-being.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies met the following criteria for inclusion in the review:

-

1.

Adults with schizophrenia or other types of schizophrenia-like psychosis, schizoaffective disorders, and bipolar affective disorder irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used, age, ethnicity and sex.

-

2.

All patients, adults, clients, in the community or in hospital.

-

3.

All relevant randomised controlled trials.

-

4.

Interventions where a primary or secondary aim was to promote exercise or physical activity.

Search Methods, and study selection

We searched the following electronic databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Biological Abstracts on Ovid, and The Cochrane Library (January 2009, repeated May 2013). The systematic search included hand searching of journals, books, cross-referencing and bulletins (e.g. brief reports/brief statement of facts). The search filter, the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy, was used to assist in the identification of randomised trials in MEDLINE [38].

The abstracts of studies were examined by RP. Full text of the studies that potentially met the eligibility criteria was obtained. Discrepancies were discussed with co-investigators. We checked articles that met the inclusion criteria for duplication of the same data.

Data extraction and analysis

Data was extracted by one author (RP) and checked for accuracy by the second (DS). Data was extracted onto prepared forms to include: participants and setting, location, description of the intervention, type of exercise, study size, methodological issues, risk of bias, results, and general comments. All analyses were conducted using Revman Manager version 5.1. We performed a PRISMA evaluation of our meta-analysis using a standard checklist of 27 items that ensure the quality of a systematic review or meta-analysis [39]. A summary measure of treatment effect was used as different outcome measures were found. The standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals was calculated as the difference in means between groups divided by the pooled standard deviation. If no standard deviations were found they were calculated from standard errors, confidence intervals, or t values [40]. Authors were contacted for missing data if analyses could not be completed. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 test. The degree of heterogeneity was categorised as the following [36]: 0% to 40% low level of heterogeneity; 30% to 60% moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity. Standard mean differences were based on the random-effects model as this would take into account any differences between studies even if there was no statistically significant heterogeneity [40].

Quality assessment

There is no agreed standardised method to assess the quality of studies in systematic reviews. We adapted the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias [40]. The following recommended domains were considered: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. Each item was rated according to the level of bias and categorised into either low, high, or unclear. The category unclear indicated unclear or unknown risk of bias [40].

Results

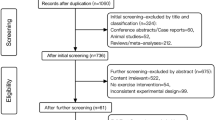

The electronic search identified 1284 potentially eligible reports. Nine hundred and thirty two were excluded on the basis of the title or abstract alone. We retrieved the full text of 216 articles and excluded a further 209 studies. The review excluded a large number of studies as they included additional components such as dietary or weight programmes (Figure 1).

All included studies had been published between 2005 and 2013. The studies varied in their setting, size, age, study intervention type, and use of outcome measures.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the sample, interventions, outcomes assessment and results are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Setting and participant characteristics

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Of these 5 were based solely in either a community or outpatient setting. The remainder comprised a combination of inpatient hospital together with community or outpatient programmes. Diversity of setting may have had an impact on the delivery and generalisability of the exercise interventions. Exercise change may be more easily achievable within a more closely supervised setting such as an inpatient ward. The sample size of studies in this review varied considerably. The largest study had 118 patients in their programme the smallest 10 individuals. The mean age of individuals ranged from 27 years to 52 years. The majority were in the age group 30–40 years. One study [41] used an older age population with a mean age of 46.9 years and one a younger group with a mean of 29.2 years [42]. The variation in age group may have affected the implementation of the programme. A younger population may have been more able to improve their level of exercise. The ethnicity of participants was described in only two studies. Beebe et al. [43] found that 54% of participants were Caucasian, 44% African-American, while Beebe et al. [41] in a small study of 10 participants, 80% were Caucasian and 20% African-American.

Exercise interventions

Each study used a different type of aerobic exercise incorporating cardiovascular exercise and resistance training. Three studies used walking as their exercise activity [41, 43, 44], while four studies used a combination of general aerobic and cardiovascular exercise [42, 45–47]. Cycling was the method of exercise activity used in the remaining study [48]. In addition to the exercise activity general information was given to all participants about exercise. Only two studies used more specific advice and guidance [43, 45]. Skrinar et al. [45] offered seminars on a range of topics such as adequate individual levels of exercise, healthy eating, stress relief, spirituality and wellness. In the remaining study Beebe et al. (2011) compared the effect of adding specific exercise advice and motivational skills to a simple walking programme [43].

Only one study [42] used a standardised programme of exercise comprising of cardiovascular and muscle strength exercises [49]. Moderate levels of exercise intensity were described in 7 out of the 8 programmes. Only Methapatara et al. [44] described the specific amount of exercise activity used in their programme. The actual amount or dose of exercise activity was not measured in the remaining studies.

Each programme varied in their frequency and duration. Some were twice a week [46] while Skrinar et al. [45] described a programme 4 times per week. The duration of the programmes lasted between 10 weeks [47] to 24 weeks [42].

Outcomes

A variety of different outcome measures were used (Table 4). This made it especially difficult to compare the results of individual interventions. Two studies used a validated measure of exercise, namely the 6-Minute Walking Distance [41, 46]. Others used measures such as body mass index [46], the number of exercise sessions attended [45], or the number of minutes walked [43].

Six studies compared the effect of exercise with usual care. A significant increase in the distance walked in 6 minutes was found in one RCT (n = 13, SMD = 1.81, CI 0.44 to 3.18, z = 2.58, p = 0.01) (Figure 2) [46]. A small non-significant reduction was found on body mass index (n = 151, SMD = -0.24, CI -0.56 to 0.08, p = 0.14; heterogeneity, Chi2 = 1.45, I2 = 0%, p = 0.69) (Figure 3). No effect was found comparing the effect of exercise on body weight (n = 77, SMD = 0.13, CI -0.32 to 0.58, p = 0.57; heterogeneity, Chi2 = 0.07, I2 = 0%, p = 0.79) (Figure 4).

There was no overall beneficial effect on negative symptoms (n = 84, SMD = -0.54, CI -1.79 to 0.71, p = 0.40) or positive symptoms of schizophrenia (n = 44, SMD = -1.66, CI -3.78 to 0.45, p = 0.12). Exercise did not lead to an improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms (n = 94, SMD = -0.26, CI -0.91 to 0.39, p = 0.43; heterogeneity, Chi2 = 3.92, I2 = 49%, p = 0.14) (Figure 5).

Data from single RCTs was available for the following outcome measures. Overall, there was no clear evidence that exercise interventions led to significant improvements in quality of life. A small non-significant increase in points of physical and mental domains were found (physical domain: n = 30, SMD = 0.45, CI -0.27 to 1.18, z = 1.22, p = 0.22: mental domain: n = 30, SMD = 0.65, CI -0.09 to 1.39, z = 1.73, p = 0.08).

The final study compared the effect of adding specific exercise advice and motivational skills to a simple walking programme [43]. No significant change was found in the attendance at walking groups, persistence, or minutes walked compared with the control.

Methodological design and quality

The review found a lack of standardisation in terms of the exercise intervention, setting and outcomes measures (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Six studies described an adequate method of randomisation. Four out of the 8 studies used satisfactory methods to conceal the allocation of treatment. Beebe et al. [41] was the only study to incorporate outcome assessors blinded to the treatment group. There was considerable variation in sample size. No study described a sample size calculation. We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias [40] (Figure 6).

One study only adequately addressed the analysis of incomplete data [44]. Data was analysed on an intention-to-treat basis with last observation carried forward on the following measures, bodyweight, body mass index, and waist circumference.

Levels of attrition varied in the included studies between 0% and 33% with a mean of 18.9%. No dropout was observed in two studies [44, 46]. Methapatara et al. [44] had no attrition in a larger study of 64 individuals, perhaps suggesting that participants in this study were more motivated to change.

Discussion

Exercise programmes found in this review had a modest beneficial effect on levels of exercise activity. Exercise did not lead to an improvement in body mass index, negative or positive symptoms of schizophrenia, or the individual’s quality of life. No effect was found on body weight or symptoms of anxiety or depression. No beneficial effect was found by the addition of specific exercise advice with motivational techniques to a simple exercise programme. The review found that many studies varied in the type of exercise programme used, setting, age group, sample size, and outcome measures. Comparison of these outcomes proved difficult. Diversity of setting may have had an impact on the delivery and generalisability of the exercise interventions. Exercise change may be more easily achievable within a more closely supervised setting such as an inpatient ward.

The exercise programmes used a variety of outcome measures. Only two studies used a validated measure of exercise [41, 46] the 6-Minute Walking Distance [50]. The majority of studies did not measure the quantity or intensity of the activity programme. It therefore proved difficult to compare the equivalent benefits of each study. We could not estimate the amount of exercise required to achieve an improvement in levels of exercise activity or mental health symptoms.

Exercise programmes resulted in only moderate or little change in measured outcomes. It is unclear why these programmes did not lead to a more significant improvement. The physical activity component of the interventions may not have been sufficiently intense. The duration of the programme may have been too short to bring about change. Delivery of the uptake of the sessions may have been inadequate to achieve a change in activity levels. The difficulties bringing about change in this population may reflect the inherent problems in this population. There are greater levels of smoking, weight problems, and co-morbid illness [51]. Individuals with greater risk factors and co-morbid physical illness may have more difficulty achieving higher levels of physical activity.

The review found that attrition levels were low with one study having no drop-out of participants. Analysis of dropout rates can give valuable information about patient characteristics and trial characteristics that affect the overall uptake of an intervention [52]. Loss to follow up after recruitment and attrition in randomised controlled trials affects the generalisability and the reliability of their results [52, 53]. Studies of health-behaviour change [54] in the general population have found varying levels of attrition. Smoking cessation interventions have been found to have attrition rates of up to 49%. Attrition rates of between 27% [55] and 32.8% [56] have been observed in weight loss studies. In people with serious mental illness similar levels of attrition have been found. Khan et al. [57] found in 45 trials of antidepressants with a total of 19,000 subjects the mean drop out rate was 37%. Explanation for the low level of attrition in this review is unclear. Low drop-out rates may suggest the participation of motivated individuals willing to change their behaviour. Several studies included individuals based in hospital wards. The structured setting of a ward environment may have reduced the levels of attrition.

Despite the health problems of this population we found only 8 randomised controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of exercise programmes for people with serious mental illness. However the number of studies in this field has steadily grown over the past few years. For example, Ellis et al. [58] in a systematic review of exercise programmes in psychosis identified one randomised controlled trial [41], while Gorczynski et al. [59] found three studies [41, 46, 60] following a systematic search completed in December 2008. However one of these studies included the effects of yoga therapy in people with schizophrenia [60]. A recent literature review by Faulkner et al. [61] found a total of 7 randomised controlled trials, however 4 of these included yoga therapy. Faulkner et al. [61] identified one additional small study [48] which was included in the review in this paper.

It is unclear why so few studies have been conducted in this field? In our review we found that many studies were excluded as they contained additional components such as dietary advice or measures to reduce weight. The focus on physical activity alone may be being lost in interventions designed to address the current increasing general concerns about obesity and metabolic problems in this population [61]. This is in addition to a general lack of well designed studies aiming to address the health problems and risk factors in this population. For example, smoking levels in people with serious mental illness remain about two to three times levels found in the general population. However relatively few randomised trials have been conducted with the primary aim of achieving smoking cessation in this population [62].

There are strengths and limitations to the results we have presented. This review found modest changes in levels of exercise activity, but no effect on symptoms of mental health. A number of limitations need to be acknowledged. Research in this field has been so far been limited with only a small number of randomised controlled trials. These tended to be small in size and of short duration. The heterogeneity of programmes affected the impact and generalisability of studies found in the review. Studies failed to quantify the amount and intensity of exercise in their programmes. Interventions tended to use non-standardised exercise programmes and a variety of outcome measures. It proved difficult to recommend from this review the most suitable and effective programme of exercise to individuals with serious mental illness. Until further research is conducted individuals with serious mental illness should be encouraged to meet the general recommendations currently advised to the general population.

Research in the future needs to focus on methods to improve levels of exercise in individuals with serious mental illness. Programmes have proved successful in the general population. There is a need to conduct well designed randomised trials of physical activity programmes. Research needs to incorporate a standardised exercise programme and outcome assessment. The duration and intensity of interventions needs to be sufficient to achieve change in levels of physical activity, mental health symptoms, or weight. New programmes need to take into account the specific needs and potential barriers to exercise of those with serious mental illness. Levels of motivation, mental health symptoms, and weight enhancing medication add additional complexity and difficulties to this process. Potential barriers to and benefits of physical activity for people with serious mental illness have been shown in previous research. McDevitt et al. [63] found that in individuals with serious mental illness symptoms of mental illness (e.g. lack of energy or volition), medication, weight gain from medication, and safety concerns restricted their ability to be active. Johnstone et al. [64] found that limited experience of previous physical activity reduced self esteem and confidence, and lack of structure or planning to their day, limited engagement in exercise activity. In the review we described three studies identified specific barriers affecting participation in their programmes. Marzolini et al. [50] found that medical and health reasons, supervised trips and family visits, and medical appointments affected participation. Skrinar et al. [45] identified several barriers such as problems with transport, financial issues, treatment factors, and conflicting schedules with other treatment programmes affected participation. Beebe et al. [43] found similar problems with the most common reasons given for non-attendance being transportation problems (22.2%), physical illness (20.6%), and conflict with another appointment (12.7%).

For clinicians there remains no clear standardised method to improve levels of physical activity in this population. The health problems of this population continue to be highlighted in many leading publications [1]. An effective method needs to be developed in this population to reduce the persistently highs levels of cardiovascular risk and mortality.

Conclusion

In conclusion we found that exercise programmes can lead to an improvement in exercise activity but had no significant effect on symptoms of mental health or body weight. However, it is clear that further research is needed with studies of larger size using comparable interventions and outcome measures.

References

The Schizophrenia Commission: The abandoned illness: a report from the Schizophrenia Commission. 2012, London: Rethink Mental Illness

Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J: A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time?. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007, 64 (10): 1123-10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123.

Laursen TM: Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011, 131: 101-104. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.008.

Nolte EC, Martin M: Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff. 2008, 27 (1): 58-71. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.58.

Weinemann S, Read J, Aderhold V: Influence of antipsychotics on mortality in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2009, 113 (1): 1-11. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.018.

Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N: Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007, 116: 317-333. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x.

Goff D, Sullivan L, McEvoy J, Meyer J, Nasrallah H, Daumit G, Lamberti S, D’Agostino R, Stroup T, Davis S, Lieberman J: A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schizophr Res. 2005, 80 (1): 45-10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.010.

De Hert MA, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, Scheen A, Peuskens J: Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Res. 2006, 83 (1): 87-93. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.855.

Newcomer JW, Haupt DW: Abnormalities in glucose regulation during antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002, 59: 337-345. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.337.

Mukherjee S, Decina P, Bocola V, Saraceni F, Scapicchio PL: Diabetes mellitus in schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1996, 37: 68-73. 10.1016/S0010-440X(96)90054-1.

Chafetz L, White M, Collins-Bride G, Cooper B, Nickens J: Clinical trial of wellness training: health promotion for severely mentally ill adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008, 196 (6): 475-10.1097/NMD.0b013e31817738de.

Filik R, Sipos A, Kehoe PG, Burns T, Cooper SJ: The cardiovascular and respiratory health of people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006, 113: 298-305. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00768.x.

Ussher M, Doshi R, Sampuran A, West R: Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with schizophrenia receiving continuous medical care. Community Ment Health J. 2011, 47 (6): 688-693. 10.1007/s10597-011-9376-y.

Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Lobos CA, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S: Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010, 123 (2-3): 225-233. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.012.

Roberts L, Roalfe A, Wilson S, Lester H: Physical health care of patients with schizophrenia in primary care: a comparative study. Fam Pract. 2007, 24: 34-40.

Paton C, Esop R, Young C: Obesity, dyslipidaemias, and smoking in an inpatient population treated with antipsychotic drugs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004, 110: 299-305. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00372.x.

Tosh G, Clifton A, Mala S, Bachner M: Physical health care monitoring for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, Art. No.: CD008298-doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008298.pub2, 3

Archie S, Hamilton Wilson J, Osborne S, Hobbs H, McNiven J: Pilot study: access to fitness facility and exercise levels in olanzapine-treated patients. Can J Psychiatr. 2003, 48 (9): 628-

Pearsall R, Hughes S, Geddes J, Pelosi A: Understanding the problems developing a healthy living programme in patients with serious mental illness: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014, 14 (1): 38-38. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-38.

McCreadie RG: Scottish schizophrenia lifestyle group. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003, 183: 534-539. 10.1192/bjp.183.6.534.

Susce MT, Villanueva N, Diaz FJ, De Leon J: Obesity and associated complications in patients with severe mental illness: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66: 167-173. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0203.

Statistics on Smoking: Statistics on Smoking: England, 2013. The Health and Social Care, Information Centre (HSCIC). 2009, http://www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/smoking13,

Brown S, Birtwistle J: The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1999, 29 (3): 697-701. 10.1017/S0033291798008186.

Green A, Patel J, Goisman R: Weight gain from novel antipsychotics drugs: need for action. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000, 22: 224-235. 10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00081-5.

Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999, 156 (11): 1686-1696.

Coodin S: Body mass index in persons with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiat. 2001, 46: 549-555.

Daumit GL, Goldberg RW, Anthony C, Dickerson F: Physical activity patterns in adults with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005, 193: 641-646. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180737.85895.60.

Ussher M, Stanbury L, Cheeseman V, Faulkner G: Physical activity preferences and perceived barriers to activity among persons with severe mental illness in the United Kingdom. Psychiatr Serv. 2007, 58 (3): 405-408. 10.1176/appi.ps.58.3.405.

Lindamer LA, McKibbin C, Norman GJ, Jordan L: Assessment of physical activity in middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008, 104: 294-301. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.040.

WHO: Global recommendations on physical activity for health. 2010, World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/en/,

Warburton DER, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, Nettlefold L, Bredin S: A systematic review of the evidence for Canada’s physical activity guidelines for adults. IJBNPA. 2010, 7 (39): 1-220.

Health Survey for England: Physical Activity and Fitness, The NHS Information Centre. The NHS Information Centre. 2009, http://www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/hse08physicalactivity,

Rimer J, Dwan K, Lawlor DA, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Morley W, Mead GE: Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5, Issue 7(Art. No.: CD004366)

Jayakody K, Gunadasa S, Hosker C: Exercise for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2014, 48: 187-196. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091287.

Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MC, Payne WR: A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. IJBNPA. 2013, 10: 135-

Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC: Physical activity and health related quality of life in the general adult population: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2007, 45: 401-415. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.017.

Knapen J, Sommerijns E, Vancampfort D, Sienaert P, Pieters G, Haake P, Probst M, Peuskens J: State anxiety and subjective well-being responses to acute bouts of aerobic exercise in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Sports Med. 2009, 43 (10): 756-759. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052654.

Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C: Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. Br Med J. 1994, 309: 1286-1291. 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6: e1000097-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2008, England: Wiley-Blackwell

Beebe LH, Tian L, Goodwin A, Allen SS, Kuldau J: Effects of exercise on mental and physical health parameters of persons with schizophrenia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005, 26: 661-676. 10.1080/01612840590959551.

Scheewe TW, Takken T, Kahn RS, Cahn W, Backx FJG: Effects of exercise therapy on cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with schizophrenia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012, 44 (10): 1834-1842. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318258e120.

Beebe LH, Smith K, Burk R, McIntyre K, Dessieux O, Tavakoli A, Tennison C, Velligan D: Effect of a motivational intervention on exercise behaviour in persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Community Ment Health J. 2011, 47: 628-636. 10.1007/s10597-010-9363-8.

Methapatara W, Srisurapanont M: Pedometer walking plus motivational interviewing programme for Thai schizophrenic patients with obesity or overweight: a 12-week, randomized, controlled trial pcn_2225374. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011, 65: 374-380. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02225.x.

Skrinar G, Huxley N, Hutchinson D, Menninger E, Glew P: The role of a fitness intervention on people with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005, 29 (2): 122-127.

Marzolini S, Jensen B, Melville P: Feasibility and effects of a group-based resistance and aerobic exercise program for individuals with severe schizophrenia: a multidisciplinary approach. Ment Health Phys Activ. 2009, 2 (1): 29-36. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2008.11.001.

Acil AA, Dogan S, Dogan O: The effects of physical exercises to mental state and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008, 15: 808-815. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01317.x.

Pelham T, Campagna P, Ritvo P, Birnie W: The effects of exercise therapy on clients in a psychiatric rehabilitation program. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993, 16 (4): 75-84.

American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians: ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167 (2): 211-277.

Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson OJ: The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985, 132: 919-922.

Weber NS, Cowan DN, Millikan AM, Niebuhr DW: Psychiatric and general medical conditions comorbid with schizophrenia in the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2009, 60: 1059-1067.

Heneghan C, Perera R, Ward A, Fitzmaurice D, Meats E, Glasziou P: Assessing differential attrition in clinical trials: self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation and type II diabetes. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007, 7 (18): 1-12.

Schulz KF, Grimes DA: Sample size slippages in randomised trials: exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet. 2002, 359: 781-785. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07882-0.

Leeman RF, Quiles ZN, Molinelli LA, Terwal DM, Nordstrom BL, Garvey AJ, Kinnunen T: Attrition in a multi-component smoking cessation study for females. Tob Induc Dis. 2006, 3 (2): 59-71. 10.1186/1617-9625-3-2-59.

Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, Greenway FL, Hill JO, Phinney SD: Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial programme: a randomised trial. JAMA. 2003, 289: 1792-1798. 10.1001/jama.289.14.1792.

Fabricatore AN, Thomas AN, Wadden A, Moore RH, Butryn ML: Attrition from randomised controlled trials of pharmacological weight loss agents: a systematic review and analysis. Obes Rev. 2009, 10 (3): 333-341. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00567.x.

Khan A, Warner WA, Brown WA: Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000, 57: 311-317. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.311.

Ellis N, Crone D, Davey R, Grogan S: Exercise interventions as an adjunct therapy for psychosis: a critical review. Br J Clin Psychol. 2007, 46: 95-111. 10.1348/014466506X122995.

Gorczynski P, Faulkner G: Exercise therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, Art. No.: CD004412-doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004412.pub2, 5

Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN: Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia – a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007, 116 (3): 226-232. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x.

Faulkner G, Gorczynski P, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K: Exercise As An Adjunct Treatment For Schizophenia. Routledge Handbook of Physical Activity and Mental Health, Ekkekakis, Panteleimon. Edited by: Ekkekakis P. 2013, London, NewYork: Routledge, 541-1

Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC: Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, Art. No.: CD007253-doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007253.pub3, 2

McDevitt J, Snyder M, Miller A, Wilbur J: Perceptions of barriers and benefits to physical activity among outpatients in psychiatric rehabilitation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006, 38 (1): 50-55. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00077.x.

Johnstone R, Nicol K, Donaghy M, Lawrie S: Barriers to update of physical activity in community-based patients with schizophrenia. J Ment Health. 2009, 18 (6): 523-532. 10.3109/09638230903111114.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/117/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

RP, DJS, and AP declared no competing interests. JG has received research funding from MRC, ESRC, NIHR, Stanley Medical Research Institute and has received donations of drugs supplies for trials from Sanofi-Aventis and GSK. He has acted as an expert witness for Dr Reddys.

Authors’ contributions

RP, AP, and JG developed the research. RP conducted the research. RP and DJS conducted the analysis. RP drafted the manuscript. AP, DJS, and JG provided input and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Pearsall, R., Smith, D.J., Pelosi, A. et al. Exercise therapy in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 14, 117 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-117

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-117