Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have consistently established high comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders (SUD). This comorbidity is even more prominent when psychiatric populations are studied. Previous studies have focused on inpatient populations dominated by psychotic disorders, whereas this paper presents findings on patients in Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs) where affective and anxiety disorders are most prominent. The purpose of this study is to compare patients in CMHCs with and without SUD in regard to differences in socio-demographic characteristics, level of morbidity, prevalence of different diagnostic categories, health services provided and the level of improvement in psychiatric symptoms.

Methods

As part of the evaluation of the National Plan for Mental Health, all patients seen in eight CMHCs during a 4-week period in 2007 were studied (n = 2154). The CMHCs were located in rural and urban areas of Norway. The patients were diagnosed according to the ICD-10 diagnoses and assessed with the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales, the Alcohol Use Scale and the Drug Use Scale.

Results

Patients with SUD in CMHCs are more frequently male, single and living alone, have more severe morbidity, less anxiety and mood disorders, less outpatient treatment and less improvement in regard to recovery from psychological symptoms compared to patients with no SUD.

Conclusion

CMHCs need to implement systematic screening and diagnostic procedures in order to detect the special needs of these patients and improve their treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidemiological studies have consistently established high comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders (SUD) [1–5]. By SUD we refer to abuse, dependence and addiction from both alcohol and other substances. This comorbidity is even more pronounced in clinical populations, particularly among homeless groups [6] and in acute psychiatric wards [7, 8] where patients with schizophrenia are particularly frequent. The prevalence of SUD varies considerably between studies, i.e. 24-50% [7–9]. This is explainable by differences in substance use levels in the catchment areas and by intake policies. Another explanation could be insufficient diagnostic practice [10]. Several studies have found under-diagnosis of SUD in psychiatric hospitals [11, 12]. There is also evidence that this group of patients do not receive health services according to their needs. Harris and Edlund found that mental health programs provided substance use services to only 31% of the clients evidencing severe mental illness with SUD [13].

These investigations have laid a sound basis for the knowledge on comorbidity among inpatient populations. Little, however, is known about the prevalence of SUD in Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs), where the clinical population differs from that of an acute psychiatric ward by having predominantly anxiety disorders and non-psychotic affective disorders. Further, it is insufficiently studied whether patients with substance use disorders differ from patients without such comorbidity and whether the CMHCs differentiate their treatment accordingly.

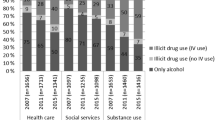

In a recent study of CMHCs in Norway, we found that only 10% of the patients had received ICD-10 diagnoses [14] of SUD [15]. The obvious explanation was under-detection by the clinicians. In addition to the ICD-10 diagnoses, the centres used the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) which includes a score on substance use problems, the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS) and the Drug Use Scale (DUS). There were some discrepancies between these measures regarding which patients were scored as having a clinical problematic use of alcohol and/or drugs. By combining these measures, however, we were able to identify all patients that were scored as having a clinically significant use of alcohol and/or other substances or diagnosed with a substance use disorder. These patients were defined as the SUD group. Patients that received a low score, indicating no clinical problem, on the substance use measures and did not receive an ICD-10 diagnosis of SUD were defined as the No SUD group. Hence, the grouping variable consists of the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS, all validated measures, together with the ICD-10 diagnoses, which were based on routine clinical assessments.

In this paper we compare the SUD group with the No SUD group

The aims of this paper are to compare the patients in CMHCs with and without SUD in regard to 1) differences in socio-demographic characteristics, 2) the level of morbidity, 3) the prevalence of different diagnostic categories, 4) differences in health services provided and 5) differences in the level of improvement in psychiatric symptoms.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study based upon data from the evaluation of the National Plan for Mental Health [16, 17]. In the original study, eight Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs) in both rural and urban areas of Norway were investigated during three separate 4 week periods in 2002, 2005 and 2007. Their total catchment area was about 450 000 inhabitants, i.e. about 10% of the Norwegian population. Specific forms were completed by clinicians, general practitioners, patients and their relatives. For this paper, we have focused on the clinician assessment forms from 2007.

The clinicians at the CMHCs, i.e. psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses and clinical social workers, were asked to complete standardized forms for all inpatients and outpatients seen within the four week period. A total of 2154 patients were included. This was about half of all patients reported to the National Patient Register (NPR) from these CMHCs in a similar 4-week period a few months later, as NPR data from the study period was unavailable. We had no information on eligible patients not included in the study. Details on the methodology are described elsewhere [15].

Research instruments

Demographic, administrative and clinical information was recorded for each patient. One primary and two secondary ICD-10 diagnoses [14] were recorded on the basis of routine clinical assessments. No structured clinical interview was used. The Health of the Nations Outcome Scales (HoNOS) [18, 19] were used to measure severity of psychiatric problems in 12 areas including substance use. The scale ranges from "no problem" (score 0) through "mild but clinically significant problem" (score 2) to "severe problem" (score 4). The Alcohol Use Scale (AUS) and the Drug Use Scale (DUS) [20, 21] were used to rate the severity of alcohol and drug use, respectively. These are 5 point scales ranging from "abstinence" (score 1) through "abuse" (score 3) to "addiction with hospitalization" (score 5). Before the first two surveys in 2002 and 2005, the clinicians at the eight CMHCs were trained in rating the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS. Before each of the three surveys they had an optional practice on case vignettes. In 2002, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for the HoNOS were calculated and ranged from 0.60 to 0.89 for the subscales (T. Ruud, personal communication). These coefficients were considered acceptable [22, 23]. We found the same prevalence rates of SUD measured by the ICD-10 diagnoses, the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS between 2002 and 2007, hence we concluded there was consistency in how these instruments were used between these years [15].

Substance use variables

We defined the SUD group as having fulfilled one or more of the following criteria: 1) a diagnosis of a substance related disorder, ICD-10 F10-19, as first, second or third diagnosis, 2) a high degree of alcohol and/or drug use measured by the HoNOS item three, scored 2-4, 3) a high degree of alcohol use measured by the AUS, scored 3-5, or 4) a high degree of drug use measured by the DUS, scored 3-5. The No SUD group was defined by not fulfilling any of the above criteria.

Socio-demographic variables

The socio-demographic variables consisted of age, gender, paid work (yes/no), in relationship (yes/no), living alone (yes/no) and ethnicity (Norwegian / non-Norwegian). No paid work was defined as "in education", "working at home", "on rehabilitation benefit", "on disability benefit", "on retirement pension" and "other". In relationship was defined as "married" or "cohabitant", while not in relationship was defined as "unmarried", "widowed", "separated" or "divorced".

Variables regarding the level of morbidity

The variables about the patients' level of morbidity were the HoNOS (except the substance use item). The substance use item of the HoNOS was used as one of the SUD group defining criteria. We categorized the HoNOS scores into two groups: 1) no clinically relevant problem (scores 0-1) and 2) clinically relevant problem (scores 2-4).

Variables regarding the prevalence of different diagnostic categories

The ICD-10 diagnoses were grouped into psychotic disorders (F20-29), mood disorders (F30-39), anxiety disorders (F40-49), personality disorders (F60-69) and other psychiatric disorders (F50-59, F70-99)

Variables regarding the health services provided

The variables about the health services provided consisted of psychiatric healthcare received during the last 12 months and additional questions about the services in total. The original 6 items of psychiatric healthcare received during the last 12 months were categorized into 3 groups; "outpatient or day service at CMHC", "inpatient service at CMHC or hospital" and "outpatient or inpatient addiction treatment". They were scored as "no", "0-6 months", "7-11 months" and "all the time". These categories were dichotomized into "no" and "0-12 months" for the analyses. The additional questions about the services in total were "is the patient treated at the right competency level" (scored as "unnecessarily high", "right" or "too low"), "are the services sufficiently comprehensive", "are the most important needs of the patient met", "are several services cooperating in making an "Individual Plan" for the patient", and "is the patient also treated in a psychiatric hospital". These questions were scored as "yes / no / I don't know/ not applicable". The latter two options were taken out of the analysis. An "Individual Plan" means a tailored, comprehensive treatment plan that all patients with a chronic disease are entitled to have according to Norwegian law.

Variables regarding the level of improvement from psychiatric symptoms

The variables were scored on a 7-point scale (1: much worse, 2: a bit worse, 3: no change, 4: a little change, 5: better, 6: much better, 7: a lot better). These items were grouped into two groups: 1) worse / no change (scores 1-3) and 2) better (scores 4-7). This scale is based on the clinicians' subjective evaluation of the patients' improvement on the day of the survey, regardless of their length of treatment.

Statistics

When comparing two groups the Student's t-test was used for continuous variables and the Pearson's chi-square test was used for categorical variables. We performed logistic regression analyses to select the adjustment variables. An α-level of 0.05 was chosen when deciding which adjustment variables to include. We included the following variables for the adjusted analyses; age, gender, in relationship, overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behaviour (honos item 1), non-accidental self-injury (honos item 2) and problems with activities of daily living (honos item 10). We also adjusted for the interaction between age and problems with activities of daily living. The explanatory variable "problems with relationships" (honos item 9) was not adjusted for in relationship, as this was not clinically meaningful. For the main analyses we did Bonferroni correction of the alfa-level due to the number of tests to avoid Type I statistical error. When an explanatory variable lost its significance due to the adjusted analyses, we ran a series of regression analyses with each adjustment variable to examine which one resulted in the greatest change in the beta coefficient of the explanatory variable. Finnally, we performed Generalized Estimating Equations analyses (GEE) with exchangeable working correlation and robust variance estimation. This was done to adjust for nesting within the CMHCs in the adjusted analyses. The GEE analyses only gave minor changes in the results compared to the regression analyses. Because gender was shown to be an important adjustment factor, we did stratified analyses by gender. As these analyses only showed small differences in the odds ratios between men and women, this issue is not elaborated any further. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 [24].

Ethics and consent issues

The study was approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Norwegian Regional Ethics Committee.

Results

Table 1 shows the background variables of the non-substance use disorder group, n = 1786, and the substance use disorder group, n = 368. The mean age amongst the patients in total was 39.3 years with no statistically significant difference between the two groups. The patients in the SUD group were more often male, less often in a relationship and more often living alone compared to the No SUD group. Even though these differences were statistically significant, the effect-sizes were quite small [25]. There were no differences in ethnicity between the two groups.

We examined if the severity of morbidity as measured by the HoNOS predicted being a SUD patient (table 2). We found that the SUD group had significantly more problems with "overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behaviour", "non-accidental self-injury", "problems with relationships", "problems with activities of daily living" and "problems with occupation and activities". These results were not altered when other variables were adjusted for. The SUD patients also seemed to have more "cognitive problems" and "problems with living conditions". These results, however, changed to a non-significant level after adjustment and we found that gender had the greatest impact in the adjusted analyses.

In this sample only 36.1% of the patients received more than one diagnosis [15] which would make it difficult to look at the prevalence of psychiatric disorders beside SUD. However, our definition of SUD is based upon the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS besides the ICD-10 diagnoses. Consequently, we can look at comorbidity between SUD and other illnesses. In the SUD group, 268 patients (72.8%) received diagnoses of somatic or psychiatric disorders other than SUD. Having a mood disorder and having an anxiety disorder was more common amongst No SUD patients and these results were not altered after adjustment.

We examined if receiving certain health services predicted being a SUD patient (table 4). We found that receiving outpatient or day service at the CMHC was less common amongst the SUD patients. This result was not altered when adjusted for other variables. Receiving inpatient service at the CMHC or hospital was more common among the SUD patients, and even though the effect-size (OR) was not altered by more than 0.3 units, the result was no longer statistically significant after adjustment. We found that in relationship had the greatest impact in the adjusted analyses. Receiving outpatient or inpatient addiction treatment was, not surprisingly, more common among the SUD patients and this was not altered after adjustment. The SUD patients were more often reported to be treated at too low a competency level, and controlling for other variables did not alter this result. The therapists did not perceive the SUD patient's services to be sufficiently comprehensive. This result, however, was altered to a non-significant level when adjusted for, even if the change in effect size was only 0.2 units. We found that overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behaviour (honos item 1) and problems with activities of daily living (honos item 10) had the greatest impact in the adjusted analyses. Having the patient's most important needs met was less common among the SUD patients, but this result also became non-significant after adjustment even if the effect size was only changed by 0.2 units. Overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behaviour (honos item 1) and problems with activities of daily living (honos item 10) had the greatest impact in the adjusted analyses. Having several services cooperating in making an individual plan for the patient was more common amongst the SUD patients, but the result became non-significant after adjustment. Gender and in relationship had the greatest impact in the adjusted analyses.

We examined if the degree of recovery predicted being a SUD patient. We found that having no change or getting worse in regard to "psychological problems" was more common among SUD patients and this result was not altered when adjusted for other variables (table 5). Having "psychiatric problems", "problems with social functioning" and "problems with practical functioning" was also more common amongst SUD patients, but changed to a borderline significant level after being adjusted with a change in effect sizes between 0.1-0.3 units. Having no change or getting worse in regard to "problems with close relations" was more common amongst the SUD patients, but changed to a non significant level after being adjusted, with a change in effect size of only 0.3 units. We found that gender was the adjustment factor that was of greatest importance in changing the significance level of all the explanatory factors. For the explanatory factors "psychiatric problems", "problems with close relations" and "problems with social functioning" the adjustment factor in relationship was also of importance.

Discussion

In this study we investigated the treatment of patients with SUD in Community Mental Health Centres (CMHCs) which typically treat patients with non-psychotic disorders such as anxiety disorders, non-psychotic affective disorders, adjustment difficulties and personality problems. The main findings are that, also in outpatient settings, the SUD group differs from the No SUD group in several ways not often systematically met with adequate treatment approaches.

Our first findings are that the patients in the SUD group are more often male, less often in a relationship and more often living alone. This is largely consistent with other epidemiological and clinical studies [4, 5, 26–28], except for one study where only the gender difference was found [29]. These findings indicate that people with SUD are a more vulnerable group. Consequently, therapists should plan treatment accordingly.

The second finding is that the SUD group has more severe morbidity as measured by the HoNOS with higher scores on five out of eleven parameters when adjusted for age, gender and in relationship. This means that the SUD group has more problems with aggressive behaviour, self harm, relationships, occupation and activities of daily living. It is therefore essential that these problems are targeted in their treatment plan. We found one other study targeting CMHCs with comparable measures [30]. In this study of patients with schizophrenia in inpatient and outpatient clinics, the misuse group was found to have higher sum scores on the HoNOS compared to the non-misuse group. In addition, Fowler et al found higher mean scores on the Symptom Check List-90 revised (SCL-90R) [31–33] on all sub-scores amongst the SUD group compared to the No SUD group amongst patients with schizophrenia [34].

The third finding is that the SUD patients have lower prevalences of anxiety and depression compared to patients without SUD. This finding is in contrast to most studies in the field indicating a higher prevalence of most comorbid disorders in SUD patients[1, 35, 36]. However, Bonsack et al found a similar pattern for anxiety and depression amongst patients in an acute psychiatric ward, but with higher prevalences for other psychiatric diagnoses amongst the SUD group compared to the No SUD group [28]. Our finding could have several explanations. Firstly, the different CMHCs may have recruited different numbers of SUD and No SUD patients due to different catchment areas. Secondly, it could be a case of competing risks; patients with SUD need less other morbidity for referral to CMHCs; thus not reflecting the comorbidity in the general population. Thirdly, less severe mental illnesses, like anxiety and depression, with comorbid SUD may be more often referred to substance use treatment centres. This could be detrimental to outcome, as patients treated in substance abuse treatment facilities may not receive adequate attention for their comorbid psychiatric illness. Bakken et al did a six year follow-up study of substance abusers in inpatient and outpatient addiction treatment facilities. They found that the number and specific types of axis 1 and axis 2 disorders with the level of SUD at admission were all independent predictors of a high level of mental distress at follow-up [37]. This underlines the need for good diagnostic and screening routines along with the competence to treat this comorbidity in an integrated treatment program.

The fourth and important finding is that patients with SUD in these CMHCs are treated differently. The patients in the SUD group receive less outpatient treatment compared to the No SUD group. In addition, the clinicians rate the patients in the SUD group as being treated at too low a competency level. One possible explanation might be that the therapists feel they lack the competence or the resources to treat these patients in an outpatient setting. In a phenomenological study of clinicians in mental health centres Deans et al found that the clinicians felt unprepared and that they were lacking knowledge of dual diagnosis patients [38]. This is in accordance with other studies that describe difficulties in implementing new knowledge and guidelines regarding comorbid patients in mental health care [39, 40]. This highlights the need for establishing and implementing good treatment strategies for this group of patients.

Our final finding is that the patients in the SUD group have poorer outcomes in regard to recovery from psychological problems. In addition, they have poorer outcomes on three out of the remaining six items at a borderline significant level after adjustment for other variables. This is in accordance with previous findings of poorer treatment outcomes for patients with co-occurring disorders [41] and is in line with the other findings of this paper, that is, that these patients have greater morbidity and receive less adequate help for their problems.

There are several limitations to this study. This study is part of an evaluation of the National Plan for Mental Health that was adapted to the study aims, the prevalence of SUD was measured by a composite adapted approach, and there was no structured clinical interview used to assess diagnoses. Further, the variables regarding the level of improvement from psychiatric symptoms were based on the clinicians' subjective evaluation of the patients' improvement, regardless if the clinician knew the patient for a longer or shorter period of time. Prior to the surveys in 2002 and 2005 the clinicians were trained in using the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS while they only had optional training on case vignettes prior to the survey in 2007. However, comparing the results from 2007 with the results from 2002 in regard to the prevalence of SUD measured on the ICD-10 F10-19 diagnoses, the HoNOS, the AUS and the DUS, we found no significant differences [15]. For further studies we would recommend to include screening procedures for SUD, i.e. the Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) [42] and the Drug Use Identification Test (DUDIT) [43], and valid diagnostic procedures, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) [44] or the Psychiatric Research Interview for Severe Mental disorders (PRISM) [45]. One might also include measures like the HoNOS, the Symptom Check List (SCL-90R) or the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [46] to enable basic comparisons between studies. Finally, the representativeness of outpatient clinics in Norway might be questioned, both according to the prevalence and type of substance use in the catchment areas and the clinical routines in the units. It is obviously important to confirm these findings in further studies. However, the findings underline the need for targeted treatment approaches for patients comorbid with SUD in psychiatric outpatient units.

Conclusion

Patients with SUD in CMHCs are more frequently male, single and living alone, have a higher level of morbidity, less anxiety and mood disorders, less outpatient treatment and have less improvement in regard to recovery from psychological symptoms compared to patients with no SUD. CMHCs need to implement systematic screening and diagnostic procedures in order to detect the special needs of substance abusing patients and improve their treatment.

Authors' information

LW is a psychiatrist and PhD-fellow at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo. HW is a psychiatrist and professor at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo. TR is a psychiatrist, professor at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, and Head of the Department of Research and Development at the Division of Mental Health Services, Akershus University Hospital. RG is a psychologist, Head of the Department of Research and Development at the Alcohol and Drug Treatment Health Trust in Central Norway and Associate professor at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo.

References

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990, 264: 2511-2518. 10.1001/jama.264.19.2511.

Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996, 66: 17-31.

Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, Walters EE, Swendsen JD, Aguilar-Gaziola S, Bijl R, Borges G, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, DeWit DJ, Kolody B, Vega WA, Wittchen HU, Kessler RC: Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998, 23: 893-907. 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00076-8.

Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [References]. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007, 64 (7): 830-842. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830.

Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [References]. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007, 64 (5): 566-576. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566.

Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M, Nestadt G, Romanoski AJ, Ross A, Royall RM, Stine OC: Health and Mental-Health Problems of Homeless Men and Women in Baltimore. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989, 262: 1352-1357. 10.1001/jama.262.10.1352.

Flovig JC, Vaaler AE, Morken G: Substance use at admission to an acute psychiatric department. [References]. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2009, 63: 113-119. 10.1080/08039480802294787.

Helseth V, Lykke-Enger T, Johnsen J, Waal H: Substance use disorders among psychotic patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric care. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009, 63: 72-77. 10.1080/08039480802450439.

Weaver T, Rutter D, Madden P, Ward J, Stimson G, Renton A: Results of a screening survey for co-morbid substance misuse amongst patients in treatment for psychotic disorders: prevalence and service needs in an inner London borough. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001, 36: 399-406. 10.1007/s001270170030.

Ananth J, Vandewater S, Kamal M, Brodsky A: Missed diagnosis of substance abuse in psychiatric patients. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1989, 40: 297-299.

Hansen SS, Munk-Jorgensen P, Guldbaek B, Solgard T, Lauszus KS, Albrechtsen N, Borg L, Egander A, Faurholdt K, Gilberg A, Gosden NP, Lorenzen J, Richelsen B, Weischer K, Bertelsen A: Psychoactive substance use diagnoses among psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000, 102: 432-438. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102006432.x.

Gogek EB: Prevalence of substance abuse in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1991, 148: 1086-

Harris KM, Edlund MJ: Use of mental health care and substance abuse treatment among adults with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005, 56: 954-959. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.954.

World Health Organization: ICD-10: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. 1992

Wusthoff LE, Waal H, Ruud T, Roislien J, Grawe RW: Identifying co-occurring substance use disorders in community mental health centres. Tailored approaches are needed. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011, 65: 58-64. 10.3109/08039488.2010.489954.

Ruud T, Reas D: Community Mental Health Centres, health services and patient satisfaction: Status and variation 2002. 2003, SINTEF Unimed, STF78 A035008 [Norwegian]

Grawe RW, Hatling T, Ruud T: Does the development of Community Mental Health Centres contribute to better health services and higher patient satisfaction? Results from investigations conducted in 2002, 2005 and 2007. Revised report [Norwegian]. 25-9-2008. SINTEF Helse 7465 Trondheim. Rapport nr SINTEF A 6169

Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, Park SB, Hadden S, Burns A: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Research and development. Br J Psychiatry. 1998, 172: 11-18. 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11.

Wing J, Curtis RH, Beevor A: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) - Glossary for HoNOS score sheet. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 174: 432-434. 10.1192/bjp.174.5.432.

Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, Hurlbut SC, Teague GB, Beaudett MS: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1990, 16: 57-67.

Mueser KT, Drake RE, Clark RE, McHugo GJ, Mercer-McFadden C, Ackerson TH: A toolkit for evaluating substance abuse in persons with severe mental illness. Cambridge, MA: the Evaluation Center@HSRI. 1995

Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977, 33: 159-174. 10.2307/2529310.

Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Equivalence of Weighted Kappa and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient as Measures of Reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973, 33: 613-619. 10.1177/001316447303300309.

SPSS for Windows, Rel. 18.0.3. 2010. 2010, Chicago: SPSS Inc

Cohen JW: Statistical power analyses for the behavioral sciences. 1988, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2

Kringlen E, Torgersen S, Cramer V: A Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological study. [References]. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 1091-1098. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1091.

Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, Singh H, Bellack AS, Kee K, Morrison RL, Yadalam KG: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophr Bull. 1990, 16: 31-56.

Bonsack C, Camus D, Kaufmann N, Aubert AC, Besson J, Baumann P, Borgeat F, Gillet M, Eap CB: Prevalence of substance use in a Swiss psychiatric hospital: Interview reports and urine screening. [References]. Addict Behav. 2006, 31: 1252-1258. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.008.

Ford L, Snowden LR, Walser EJ: Outpatient mental health and the dual-diagnosis patient: Utilization of services and community adjustment. Eval Program Plann. 1991, 291-298.

Naeem F, Kingdon D, Turkington D: Cognitive behaviour therapy for Schizophrenia in patients with mild to moderate substance misuse problems. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2005, 34: 207-215. 10.1080/16506070510010684.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale--preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973, 9: 13-28.

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF: The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1976, 128: 280-289. 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280.

Derogatis LR: The SCL-90 Manual I: Scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90. 1977, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Unit

Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, Lewin TJ: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998, 24: 443-455.

Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [References]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007, 64: 830-842. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830.

Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. [References]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007, 64: 566-576. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566.

Bakken K, Landheim AS, Vaglum P: Axis I and II disorders as long-term predictors of mental distress: a six-year prospective follow-up of substance-dependent patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007, 7: 29-10.1186/1471-244X-7-29.

Deans C, Soar R: Caring for clients with dual diagnosis in rural communities in Australia: The experience of mental health professionals. [References]. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005, 268-274.

Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophr Bull. 1998, 24: 11-20.

Moser LL, Deluca NL, Bond GR, Rollins AL: Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectr. 2004, 9: 926-36. 942

Baker KD, Lubman DI, Cosgrave EM, Killackey EJ, Yuen HP, Hides L, Baksheev GN, Buckby JA, Yung AR: Impact of co-occurring substance use on 6 month outcomes for young people seeking mental health treatment. [References]. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007, 896-902.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M: Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993, 88: 791-804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x.

Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F: Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res. 2005, 11: 22-31. 10.1159/000081413.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). 2002, New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute

Hasin DS, Trautman KD, Miele GM, Samet S, Smith M, Endicott J: Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM): reliability for substance abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 1996, 153: 1195-1201.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980, 168: 26-33. 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/93/prepub

Acknowledgements

Ingvild Dalen, Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo, for valuable statistical advise.

Solfrid Lilleeng, SINTEF Research Centre, for valuable help in coding the data.

Jørgen Bramness, Professor and Head of the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, for valuable statistical councelling.

Priscilla Martinez, Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research, for valuable help in the final revising of the manuscript.

SINTEF Health Research for the use of the data material.

The study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council.

The people to be acknowledged have given their written consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All the authors fulfil the Vancouver requirements for authorship. TR and RG have been involved in the conception, design and acquisition of the data. HW and LW have been involved in analysing and interpreting the data. LW has drafted the manuscript. All authors have been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the version to be published.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wüsthoff, L.E., Waal, H., Ruud, T. et al. A cross-sectional study of patients with and without substance use disorders in Community Mental Health Centres. BMC Psychiatry 11, 93 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-93

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-93