Abstract

Background

Non-adherence to prescribed treatments is the primary cause of treatment failure in pediatric long-term conditions. Greater understanding of parents and caregivers’ reasons for non-adherence can help to address this problem and improve outcomes for children with long-term conditions.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Medline, Embase, Cinahl and PsycInfo were searched for relevant studies published in English and German between 1996 and 2011. Papers were included if they contained qualitative data, for example from interviews or focus groups, reporting the views of parents and caregivers of children with a range of long-term conditions on their treatment adherence. Papers were quality assessed and analysed using thematic synthesis.

Results

Nineteen papers were included reporting 17 studies with caregivers from 423 households in five countries. Long-term conditions included; asthma, cystic fibrosis, HIV, diabetes and juvenile arthritis. Across all conditions caregivers were making on-going attempts to balance competing concerns about the treatment (such as perceived effectiveness or fear of side effects) with the condition itself (for instance perceived long-term threat to child). Although the barriers to implementing treatment regimens varied across the different conditions (including complexity and time-consuming nature of treatments, un-palatability and side-effects of medications), it was clear that caregivers worked hard to overcome these day-to-day challenges and to deal with child resistance to treatments. Yet, carers reported that strict treatment adherence, which is expected by health professionals, could threaten their priorities around preserving family relationships and providing a ‘normal life’ for their child and any siblings.

Conclusions

Treatment adherence in long-term pediatric conditions is a complex issue which needs to be seen in the context of caregivers balancing the everyday needs of the child within everyday family life. Health professionals may be able to help caregivers respond positively to the challenge of treatment adherence for long-term conditions by simplifying treatment regimens to minimise impact on family life and being aware of difficulties around child resistance and supportive of strategies to attempt to overcome this. Caregivers would also welcome help with communicating with children about treatment goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-adherence is the primary cause of treatment failure in pediatric long-term conditions [1]. Internationally, a third to a half of all prescribed treatments are not adhered to and the rates of non-adherence amongst children and adolescents with long-term conditions is higher than amongst adults [2].

‘Adherence’ is ‘the extent to which the patient’s behaviour matches agreed recommendations from the prescriber’ [3]. We prefer it to the term ‘compliance’ because it includes, but does not presume, the possibility of patient involvement in the treatment decision making process. We do not use the term ‘concordance’ because it assumes a shared decision making process between patients and doctors [4]. Although shared decision making would ideally occur in all clinical encounters, this cannot be assumed.

Quantitative research into barriers to treatment adherence has identified a range of factors including: costs and access to treatments; complexity and demands of treatment regimen; lack of social support and depression [4]. Research into promoting treatment adherence has found that the most effective interventions are complex and include combinations of more convenient care, information, reminders, specific behavioural change techniques [3–5] and involving patients in the decision-making process [6]. Adherence interventions amongst pediatric populations also show that multicomponent interventions are most effective. [7, 8] However, the effect sizes are inconsistent across studies and settings [9], effect sizes are small and more research is needed [10].

There is a recognised need for qualitative research to understand the complex behaviour of treatment adherence [3]. A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative papers on treatment adherence that focussed primarily on adults [11] found a reluctance to take medicines in general; a preference to take as little as possible; a widespread practice of personal testing of medicines, mainly for adverse effects; and patients modifying treatment regimens to make them more acceptable.

Treatment adherence in pediatric care has been less extensively studied [12], yet influences appear even more complex than in the care of adults. For example, the burden of treatment generally lies with caregivers rather than with the patients themselves. Additionally, whereas in adults the therapeutic relationship is between the medical team and the patient, in pediatric care there is a ‘therapeutic triad’ with communicative interactions between parent -professionals; child - professionals and parent - child [6].

Qualitative research is one way of better understanding the views of patients and caregivers. Whereas quantitative research and clinical trials provide strong evidence about mechanisms of adherence and effectiveness of interventions, qualitative research exploring caregivers’ experiences of treatment adherence might offer additional insights. These could inform the development of new interventions or enhance the understanding of clinicians who communicate with families regarding treatment adherence in their everyday practice. There has been no review of the qualitative literature focusing on treatment adherence in pediatrics even although there are a number of such studies which could be synthesised. We therefore conducted a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature to investigate parents and caregivers’ accounts of their reasons for adherence and non-adherence to prescribed treatments in pediatric long-term medical conditions.

Methods

The synthesis of qualitative research is an emerging field and several approaches exist [13]. We used the principles of thematic synthesis, an established approach previously used in public health [14].

Selection criteria

Papers included in our study had to report qualitative findings, for example from interviews and focus groups, providing insight and meaning into treatment adherence or non-adherence from the perspective of parents and other caregivers (but not health professionals) of children with long-term conditions. (This topic did not need to be the primary focus of the original research studies). As our focus was on caregiver adherence, included studies had report on data from caregivers of children aged 12 or younger (studies solely reporting the views of caregivers of teenagers were excluded).

Our focus was on clinical conditions that would widely be viewed as ‘long-term illnesses’. We therefore included conditions such as asthma and diabetes but excluded behavioural, developmental and/or mental health conditions (such as autism) as well as visual and hearing impairments. Papers relating to adherence to treatments for the prevention of rejection following organ transplant were also excluded as these formed a substantial number of papers and would have led to an excessive number and heterogeneity of papers. We included studies where caregivers were given specific treatment advice and instructions but excluded studies where general advice was given. So studies reporting on parents delivering physiotherapy in juvenile chronic arthritis were included but not studies where parents were encouraging children with asthma to be more physically active. Thematic synthesis necessitates having a depth of data which can be brought together. Included papers therefore had to provide a substantial amount of data on treatment adherence or non-adherence (not just brief descriptions of these within the wider context of coping with chronic illness generally). As such, at least half the findings presented in included studies had to focus specifically on treatment adherence or non-adherence by caregivers. We excluded papers which solely reported treatment adherence in developing countries, as the barriers to treatment adherence would differ substantially in this context. To avoid misinterpreting reported findings, included papers were in English or German – languages spoken by the researchers.

Literature search

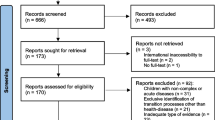

Four electronic databases were searched in December 2011 (Medline, Embase, Cinahl and PsycInfo) with search strategies that used both Medical Subject Headings terms and text words (see Table 1). Although there are differences in terms of meaning between adherence, concordance and compliance, all three terms were searched for to increase the sensitivity of our searches. Databases were searched from the last 15 years, as qualitative research is not well indexed prior to this date and this reflects the date of the earliest papers on this topic that we are aware of [15]. Additional papers were sought by writing to authors and examining reference lists of included papers. Titles and abstracts were initially screened and if these indicated that the paper might meet the inclusion criteria, the full text paper was retrieved and examined against our inclusion criteria. Where there was any uncertainty about inclusion, for instance if a paper provided data on treatment adherence by caregivers but of insufficient depth for synthesis, this was discussed within the research team. Further details of literature search and screening are shown in Figure 1.

Literature searching & screening flowchart. Based on PRISMA reporting flowchart [16].

Quality of reporting

Papers meeting our inclusion criteria were quality assessed using an adapted version of the CASP quality assessment tool [17] (see Table 2). We used quality appraisal primarily to enable a critical review of each paper and to assess transparency of reporting of methods, but not as a means of excluding papers, given the debate over essential criteria for reporting qualitative studies [18]. Assessing potential papers against inclusion criteria and assessing quality was completed independently by two researchers (MS, NR, SW and AG) working independently and then collaborating to compare findings. Any differences were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and analysis

Thomas and Harden [14] describe three stages in thematic synthesis: coding text; developing descriptive themes and generating analytical themes. Data were extracted from included papers in two phases. In phase 1, details about study design and participants were extracted onto a previously adapted template [19]. In phase 2, the findings and discussion from included papers relating to treatment adherence (or non-adherence) by caregivers were imported into Nvivo9 software. In order to develop descriptive themes, three reviewers independently coded this text in 10 original papers – these were chosen as they covered different conditions and provided a breadth of findings – to identify provisional themes according to meaning and content (MS, NR and SW). These three reviewers then discussed their independently derived themes and agreed a preliminary coding frame of main themes. This coding frame was then applied to data in all papers. Data were coded independently by two reviewers with any differences between coders resolved through discussion and the coding frame refined where necessary.

Once all papers were coded and data presented as descriptive themes, we needed to ‘go beyond’ the original author interpretations of their data to provide analytical themes. This was an iterative and inductive process in which we explored relationships between the different papers and long-term conditions to create new insight and meaning. This process involved extensive team discussion and reflection to refine descriptive themes and develop over-arching analytical themes derived from all included studies.

Results

506 possible studies were assessed against our inclusion criteria with 17 studies (19 papers) finally identified as meeting our study inclusion criteria. These papers presented rich data from qualitative studies reporting caregivers views on treatment adherence or non-adherence in a range of pediatric long-term conditions (predominantly asthma, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, cystic fibrosis, HIV, diabetes) from 423 households in five countries published over an 15 year period (1996–2011) (Table 3). Caregivers included in these studies were parents, foster parents and other relatives.

Findings

Overall, findings regarding caregiver treatment adherence and non-adherence were similar across conditions yet, as the impact on daily life from both the treatment and the condition varied widely, there were some notable differences between conditions. Findings that contribute to explaining treatment adherence can be summarised according to six main themes: (1) beliefs and about the condition or the treatment (2) difficulty of treatment regimen; (3) child resistance; (4) relationships within families; (5) preserving ‘normal life’; and (6) input from health professionals. Each theme is briefly described below with additional details provided in Table 4 and Table 5. We then present our analytical overview; balancing competing priorities around treatment adherence needs to be viewed in the broadest context, including preserving family relationships and promoting ‘normal life’ for the child.

Caregiver beliefs about long-term conditions and treatments

This was the most commonly reported theme (noted across all 19 papers) and it had a major impact on caregiver decisions regarding treatment adherence and non-adherence. This theme consisted of two sub-themes: caregiver beliefs, concerns or fears about the condition (such as its perceived long-term threat to the child) and caregiver beliefs about the treatment (including perceived effectiveness or fear of side effects).

Thirteen papers described how caregivers attempted to weigh up beliefs about the child’s long-term condition against positive or negative beliefs about the treatment and other barriers to treatment (Table 5). For instance, in asthma, fears about potential side effects from inhaled steroids were weighed against fears of acute exacerbations [20, 21], leading caregivers to carry out ‘trials’ of withholding regular medication to observe whether their child still needed them [22].

All the studies of families with children with cystic fibrosis described the tension caregivers experienced between having to overcome the many barriers to treatment adherence (especially time-consuming therapy and child resistance) against their strong belief that adherence to, at least some of, the prescribed treatments would keep their child healthy for longer [23–26]. One author described caregivers as ‘being caught between the illness, the child and the therapy’ [26]. Caregivers knew, for example, that cystic fibrosis meant their child would die prematurely but that chest physiotherapy might delay this, yet they also saw how much their child disliked and resented such treatment [26].

Difficulty of treatment regimen

Barriers to adherence relating to specific treatment regimens was identified as a theme in approximately half of the included papers (Table 5). Caregiver reported difficulties included time-consuming or complex treatment regimens (such as chest physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis) [23–26] or unpalatable treatments or those with side effects (particularly HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) for HIV) [27–29] or painful treatments (physiotherapy for juvenile arthritis [30]).

Many papers reported caregivers’ descriptions of practical strategies and routines they had developed to cope with the difficulty of the treatment regimen. Some caregivers spoke positively about establishing a routine and how this could help with remembering treatments. Routines were also considered beneficial in fitting treatment regimens into family life and could help avoid child resistance developing as children came to expect their treatment as part of ‘normal’ routine.

Conversely, some caregivers perceived the rigidity of a routine as problematic, for example in children with diabetes, where caregivers described the ‘constant vigilance’ following initial diagnosis and adherence to a rigid routine gradually developed into ‘flexible adherence’ as caregivers gained confidence and were more able to adapt treatment regimens to ‘normal life’ [31]. Furthermore, some studies in cystic fibrosis [26] and HIV [28] found that caregivers believed a more flexible approach to adherence could promote the emotional well-being of the family and, therefore, the affected child.

Child resistance

Conflicts with children over treatment adherence were widely reported by caregivers, across all conditions, as a barrier to adherence and a source of stress (Table 4 and Table 5). Some caregivers described a pattern of repetitive resistance, where the child fiercely refused most treatments leading to daily ‘battles’ and caregiver fatigue. This was particularly problematic where the treatment was aversive (unpalatable or caused adverse side-effects) or time-consuming (physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis or juvenile arthritis) as children resented the boredom of these activities.

Caregivers were not only concerned about the impact of child resistance on adherence and treatment of their condition, but they also faced dilemmas about how best to deal with it. Some caregivers were less able or willing to cope with the distress of, or dissent from, the child and these families tended to discontinue the treatment [30].

The child’s age and development influenced how caregivers viewed their responsibility for treatment adherence, their experience of child resistance and how to deal with it. A further tension was identified in diabetes and asthma, with caregivers wishing to encourage the child’s independence in managing their own care while also wishing to ensure that treatment adherence was as good as possible through parental involvement [21, 32].

Impact on relationships within families

Perceived threats and strains to family relationships was a recurring theme relating to treatment adherence particularly in papers on cystic fibrosis, HIV and juvenile arthritis (Table 5). Family relationships were considered threatened through (i) a child’s repetitive resistance to treatment leading to conflict, (ii) difficulties with handing responsibility for treatment over to older children, (iii) the child holding a different view of the treatment or condition than the parent or parents holding differing views from each other. For example, Williams et al. [26] highlighted that children may take a different view of cystic fibrosis treatment from their caregivers associating treatment with illness and infection, rather than with health and well-being [26]. Conflict between caregivers and children over treatments were sometimes directly described as resulting in non-adherence, as illustrated in Table 4 by the quote from a caregiver of a child with HIV.

Preserving ‘normal life’

Across all the long-term conditions, authors identified how promoting ‘normal life’ for the child with a long-term condition was a parental/caregiver priority yet treatment adherence challenged this goal, particularly where treatments were time-consuming or where child resistance developed (Table 5). Time-consuming therapies, such as physiotherapy for juvenile arthritis or cystic fibrosis, presented a difficulty as this was time spent to the exclusion of other family members and other activities; some caregivers felt that the regimen had to be contained so that it did not impinge on ‘normal’ activities [26].

Highly visible therapies, such as wearing splints for juvenile arthritis [33], were also viewed as threats to ‘normal life’ by drawing attention to the child’s condition. This was particularly problematic for caregivers of children with HIV, who reported difficulties giving treatment to children in front of others who were unaware of their child’s HIV status, due to the perceived stigma of the condition [27]. Conversely, in asthma, there was evidence that inhalers were viewed as facilitating normality as they allowed children to join in activities which would otherwise have been difficult for them [34]. In diabetes, treatment was also viewed as facilitating normal life in that it kept the child well [31].

Input from health professionals

Input from health professionals was mentioned by caregivers across all conditions as influencing their beliefs about the illness and the treatment. Health professionals were seen as a source of advice on how to overcome difficulties with the treatment regimen; or to help communicate with their child about treatment goals.

Where treatments were not observed to be immediately beneficial, a strong relationship between caregivers and health professionals appeared to have an important role in promoting treatments [25, 35]. Findings from HIV studies reflected that the caregivers viewed healthcare professionals as a source of support in overcoming challenges to adherence, for instance for advice about dealing with un-palatability and gastro-intestinal side-effects [28, 29]. Some caregivers felt that they were unable to get the child to fully adhere to the regimen and needed the help of health professionals, who were better able to encourage the child to implement their treatment [25, 28].

Although input from health professionals was generally seen in a positive way, there were some cases where caregivers and health professionals did not share the same perspectives. For example, one study reported that caregivers felt medical staff tried to engage with their child before that child was ready to be involved in treatment decisions [29]. Also, some caregivers did not always hold the same views as their health professionals regarding a condition. For instance, caregivers did not always see asthma as long-term condition requiring constant preventative treatment or they did not perceive inhaled steroids to be a safe treatment [35, 36].

Analytical overview

Drawing together the themes from all included studies allowed us to gain an overview of the full range of factors that influence caregivers in their everyday management of treatment adherence for long term pediatric conditions. While individual authors have highlighted concerns of parents regarding balancing competing concerns about the treatment and the condition, or between child resistance and strict adherence, this overview demonstrates that this balance needs to be viewed in the widest context, including preserving family relationships and promoting ‘normal life’ for the family. Caregivers may have been implicit or explicit in their descriptions of how they attempted to reconcile their competing concerns or priorities but all experienced tensions and this complex juggling of the needs of the child and the family reflects the juggling act that caregivers carry out in everyday life.

Discussion

This study thematically synthesised 19 papers from 17 studies in 5 countries reporting on how caregivers manage treatments in a range of long-term conditions. Our findings reveal that a wide range of factors contributed to treatment adherence (or non-adherence) in these pediatric long-term conditions. The papers we synthesised were diverse in terms of long-term conditions, types of caregivers and the age range of children cared for but one over-arching theme arising from all these studies was that caregivers sought to balance many competing concerns about the condition and its treatment in the context of everyday family life. Their ability to adhere to a treatment regimen depended on several key factors – difficulty associated with its implementation (such as treatment side-effects) and child resistance and the threat that these factors posed to family relationships and ‘normal life’ for the child and any siblings. Balancing these competing concerns was on-going for caregivers of children with long-term conditions and they worked hard to overcome challenges on a day-to-day basis. Health professionals have a key role in supporting treatment adherence in pediatric long-term conditions.

A strength of this review is that through drawing together qualitative findings on diverse pediatric long-term conditions, we were able to see patterns that may not otherwise have emerged and identify the full range of factors influencing treatment adherence and the needs of caregivers in relation to prescribed treatment regimens. Many of our findings support those of the meta-ethnography of qualitative research on treatment adherence in adults [11]. For example, both reviews found that people modify treatment regimens to make them more acceptable and to ‘fit’ with everyday life.

Our findings provide empirical support for the concept of a ‘therapeutic triad’ in pediatric adherence [6] with participants in these studies citing both their child and health professionals as important in influencing their adherence practices. Such findings can inform everyday consultations in pediatric long-term conditions. The additional complexity in the pediatric encounter of the ‘therapeutic triad’ rather than a ‘therapeutic dyad’ represents a challenge to health professionals to develop sophisticated communication strategies. For instance, health professionals may be able to assist parents and caregivers by helping the child view their treatment as enabling health and a ‘normal life’, rather than representing illness and interference [26]. Participants in these studies wished for more support from health professionals in devising simpler treatment regimens that take account of family life, seeking solutions to barriers to adherence and communicating with their child about adherence. Providing opportunities to discuss barriers to adherence before repetitive resistance develops could be a great help to caregivers.

A limitation of our review is that the participants included in these studies may not have been fully representative of less adherent families in some cases. A further limitation is that we considered only papers which included data from caregivers – we did not include papers reporting children’s views about treatment adherence. Our need to include studies with children of varying ages meant we excluded papers on other long-term conditions such as sickle cell anaemia and inflammatory bowel disease which focused on teenagers only. A synthesis of qualitative studies focusing on the views of children and young people with long-term conditions would be therefore valuable in future.

Conclusions

In practice, treatment adherence by caregivers is the result of a complex balancing act of competing concerns including their beliefs about a condition and its treatment, managing child resistance, preserving family relationships and promoting ‘normal life’ for the family. Health professionals need to understand the complexities surrounding treatment adherence and non-adherence in order to support caregivers in developing treatment regimens that minimise impact on everyday life and family relationships. This means simplifying regimens and being prepared to discuss strategies to address or pre-empt child resistance, including communicating treatment goals to the child so far as possible.

References

World Health Organisation: Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. 2003, Geneva: World Health Organisation

Carter S, Taylor D, Levenson R: A question of choice-compliance in medicine taking. A preliminary review. Medicines Partnership. 2003, URL http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/browsable/DH_5354368, 2

Nunes V, Neilson J, O’Flynn N, Calvert N, Kuntze S, Smithson H, Blair J, Bowser A, Clyne W, Crome P, Haddad P, Hemingway S, Horne R, Johnson S, Kelly S, Packham B, Patel M, Steel J: Clinical Guidelines and Evidence Review for Medicines Adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. 2009, London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners

Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N, Elliott R, Morgan M, Cribb A: Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine-taking. 2005, London: NCCSDO

Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X: Interventions for enhancing adherence to prescribed medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, Art No : CD000011-doi:10 1002/14651858 CD000011 pub3 2012, Issue 2

De Civita M, Dobkin PL: Pediatric adherence as a multidimensional and dynamic construct, involving a triadic partnership. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004, 29 (3): 157-169. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh018.

Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T: Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008, 33 (6): 590-611.

Hood KK, Rohan JM, Peterson CM, Drotar D: Interventions with adherence-promoting components in pediatric type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of their impact on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33 (7): 1658-1664. 10.2337/dc09-2268.

Graves MM, Roberts MC, Rapoff M, Boyer A: The efficacy of adherence interventions for chronically ill children: a meta-analytic review. [Review]. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010, 35 (4): 368-382. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp072.

Bain-Brickley D, Butler LM, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW: Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, 12: CD009513

Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, Yardley L, Pope C, Daker-White G, Campbell R: Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61: 133-155. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063.

Costello I, Wong IC, Nunn AJ: A literature review to identify interventions to improve the use of medicines in children. Child Care Health Dev. 2004, 30 (6): 647-665. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00478.x.

Ring N, Jepson R, Ritchie K: Methods of synthesising qualitative research studies for health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011, 27: 384-390. 10.1017/S0266462311000389.

Thomas J, Harden A: Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008, 8: 45-10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Knafl K, Breitmayer B, Gallo A, Zoeller L: Family response to childhood chronic illness: description of management styles. J Pediatr Nurs. 1996, 11: 315-326. 10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80065-X.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 7: e1000097-

Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, Thorson A: Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008, 8: 21-10.1186/1471-2288-8-21.

Noyes J, Popay J, Pearson A, Hannes K, Chapter 20: Qualitative research and cochrane reviews. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.1 (updated March 2011). Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/cochrane/handbook (accessed May 2012)

Ring N, Jepson R, Hoskins G, Wilson C, Pinnock H, Sheikh A, Wyke S: Understanding what helps or hinders asthma action plan use: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2011, 85 (2): e131-e143. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.025.

Bokhour BG, Cohn ES, Cortes DE, Yinusa-Nyahkoon LS, Hook JM, Smith LA, Rand CS, Lieu TA: Patterns of concordance and non-concordance with clinician recommendations and parents’ explanatory models in children with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2008, 70 (3): 376-385. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.007.

Peterson-Sweeney K, McMullen A, Yoos HL, Kitzman H: Parental perceptions of their child’s asthma: management and medication use. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003, 17 (3): 118-125.

Callery P, Milnes L, Verduyn C, Couriel J: Qualitative study of young people’s and parents’ beliefs about childhood asthma. Br J Gen Pract. 2003, 53: 185-190.

Foster C, Eiser C, Oades P, Sheldon C, Tripp J, Rice S, Trott J: Treatment demands and differential treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis and their siblings: patient, parent and sibling accounts. Child Care Health Dev. 2001, 27 (4): 349-364. 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2001.00196.x.

Slatter A, Francis S, Smith F, Bush A: Supporting parents in managing drugs for children with cystic fibrosis. Br J Nurs. 2004, 13 (19): 1135-1139.

Williams B, Mukhopadhyay S, Dowell J, Coyle J: Problems and solutions: Accounts by parents and children of adhering to chest physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007, 29 (14): 1097-1105. 10.1080/09638280600948060.

Williams B, Coyle J, Dowell J, Mukhopadhyay S: Living with cystic fibrosis: An exploration of the impact of beliefs on emotional coping and motivation to adhere to treatment regimes among parents of children with cystic fibrosis in Scotland. Int J Disabil Community Rehabil. 2007, 6 (1):

Hammami N, Nostlinger C, Hoeree T, Lefèvre P, Jonckheer T, Kolsteren P: Integrating adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy into children’s daily lives: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2004, 114 (5): e591-e597. 10.1542/peds.2004-0085.

Merzel C, Vandevanter N, Irvine M: Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among older children and adolescents with HIV: a qualitative study of psychosocial contexts. AIDS Patient Care Stds. 2008, 22 (12): 977-987. 10.1089/apc.2008.0048.

Wrubel J, Moskowitz JT, Richards TA, Prakke H, Acree M, Folkman S: Pediatric adherence: perspectives of mothers of children with HIV. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (11): 2423-2433. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.034.

Britton CA, Moore A, Views from the inside, Part 3: How and why families undertake prescribed exercise and splinting programmes and a new model of the families’ experience of living with juvenile arthritis. Br J Occup Ther. 2002, 65 (10): 453-460.

Sullivan-Bolyai S, Knafl K, Deatrick J, Grey M: Maternal management behaviors for young children with type 1 diabetes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003, 28 (3): 160-166. 10.1097/00005721-200305000-00005.

Schilling LS, Knafl KA, Grey M: Changing patterns of self-management in youth with type I diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006, 21 (6): 412-424. 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.01.034.

Schroder N, Crabtree MJ, Lyall-Watson S: The effectiveness of splinting as perceived by the parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Br J Occup Ther. 2002, 65: 75-80.

Prout A, Hayes L, Gelder L: Medicines and the maintenance of ordinariness in the household management of childhood asthma. Sociol Health Illn. 1999, 21 (2): 137-162. 10.1111/1467-9566.00147.

Klok T, Brand PL, Bomhof-Roordink H, Duiverman EJ, Kaptein AA: Parental illness perceptions and medication perceptions in childhood asthma, a focus group study. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100: 248-252. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02024.x.

van Dellen QM, van Aalderen WMC, Bindels PJE, Öry FG, Bruil J, Stronks K: Asthma beliefs among mothers and children from different ethnic origins living in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8 (1): 380-10.1186/1471-2458-8-380.

Sullivan-Bolyai S, Deatrick J, Gruppuso P, Tamborlane W, Grey M: Constant vigilance: mothers’ work parenting young children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003, 18 (1): 21-29. 10.1053/jpdn.2003.4.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/63/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work is produced by Miriam Santer under the terms of post-doctoral research training fellowship issued by the NIHR. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, The National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design and analysis. MS, NR, AG and SW reviewed papers and carried out data extraction and coding. MS was responsible for drafting the paper and all authors revised the paper and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Santer, M., Ring, N., Yardley, L. et al. Treatment non-adherence in pediatric long-term medical conditions: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies of caregivers’ views. BMC Pediatr 14, 63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-63

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-63