Abstract

Background

Our purpose was to evaluate the impact of lifestyle behavior modification on glycemic control among children and youth with clinically defined Type 2 Diabetes (T2D).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies (randomized trials, quasi-experimental studies) evaluating lifestyle (diet and/or physical activity) modification and glycemic control (HbA1c). Our data sources included bibliographic databases (EMBASE, CINAHL®, Cochrane Library, Medline®, PASCAL, PsycINFO®, and Sociological Abstracts), manual reference search, and contact with study authors. Two reviewers independently selected studies that included any intervention targeting diet and/or physical activity alone or in combination as a means to reduce HbA1c in children and youth under the age of 18 with T2D.

Results

Our search strategy generated 4,572 citations. The majority of citations were not relevant to the study objective. One study met inclusion criteria. In this retrospective study, morbidly obese youth with T2D were treated with a very low carbohydrate diet. This single study received a quality index score of < 11, indicating poor study quality and thus limiting confidence in the study's conclusions.

Conclusions

There is no high quality evidence to suggest lifestyle modification improves either short- or long-term glycemic control in children and youth with T2D. Additional research is clearly warranted to define optimal lifestyle behaviour strategies for young people with T2D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, the prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) in the pediatric population is increasing, most notably among 15 - 18 year olds [1–4]. At diagnosis, most boys and girls with T2D are overweight or obese, have a positive family history of T2D, are peri- or post-pubertal, and present with metabolic risk factors (e.g., dyslipidemia) [5]. With the early onset of this chronic condition and the associated co-morbidities, a life-long reduction in quality of life and premature mortality due to micro- and macro-vascular complications can be expected [6]. To address this health challenge resulting from pediatric T2D, effective and efficient management strategies are necessary.

Strong evidence supports the role of lifestyle modification to prevent (or at least delay) T2D in adults [7–11]. On this basis, many current clinical practice guidelines for adults with T2D recommend lifestyle modifications that include improving dietary quality as well as increasing the quantity and quality of physical activity to promote weight management and improve glycemic control [12–14]. Current treatment guidelines for children and youth with T2D do not differ from adult recommendations. Among children and youth who are asymptomatic (i.e., free of polyuria, polydipsia, or ketoacidosis) at diagnosis, intensive lifestyle counseling is recommended to achieve good glycemic control (i.e., HbA1c < 7.0% or fasting plasma glucose < 6.6 mmol/L) within 3 to 6 months [13–17]. If this clinical target is not achieved, initiation of metformin, an oral hypoglycemic agent, is recommended; in some cases, insulin therapy may also be necessary [16, 18].

Although there is little data currently available on treatment patterns for children with T2D, it appears most boys and girls with T2D are treated pharmacologically [12]. It is not known whether this is a reflection of poor adherence to lifestyle modifications in children and youth or because clinicians' perceptions of and experiences with lifestyle recommendations and interventions are less effective for managing T2D in this population. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a systematic review to evaluate the impact of lifestyle behavior modification on glycemic control among children and youth with clinically defined T2D.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

A research librarian, with input from the research team, developed and implemented a comprehensive search strategy in selected high-yield electronic databases (EMBASE, CINAHL®, Cochrane Library, Medline®, PASCAL, PsycINFO®, and Sociological Abstracts) from their date of inception until October 2007. An updated search was completed in May 2009 (See Additional file1 for search terms). Relevant articles were also sought by searching the reference lists from articles retrieved for detailed review as well as related review articles published from January 2002 onward. Personal contact was established with content experts and authors of selected review articles to ensure relevant publications were not missed. No language restrictions were applied in this search strategy.

Study Inclusion and Selection Criteria

We included all studies designed to evaluate the impact of lifestyle modification (diet and/or physical activity) on glycemic control (HbA1c) in children or youth with T2D. Lifestyle modification and glycemic control among children and youth with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose were not included. Similarly, the use of anti-diabetic drug therapies was not formally assessed. However, if a lifestyle modification group was included in any study design, the data were considered for inclusion. Studies were excluded if they did not include a comparison group or were not relevant to children and youth.

Two reviewers (STJ and MC) independently reviewed all abstracts and references. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: original research, participants ≤18 years of age with T2D, evaluated the effect of lifestyle modification (diet and/or physical activity) on glycemic control (HbA1c). Inter-observer agreement for study inclusion was high (κ = 0.92). Once the initial review was complete, a third investigator (GDCB) resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

Quality Assessment

Assessment of the methodologic quality of included studies was completed using criteria from Downs and Black [19], which assessed study characteristics including internal and external validity, power, and reporting. A maximal quality index (QI) score was given to selected studies. A QI score >20 rated good, 11 to 20 rated moderate and <11 rated poor [19]. Two reviewers (STJ and MC) independently completed quality assessments of included studies. Any discrepancies were resolved through third party discussion (GDCB).

Results

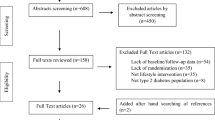

Figure 1 shows the selection process for this systematic review. From the 4,572 publications identified by reviewing titles and abstracts, 61 manuscripts were selected for complete review. Of these manuscripts, 19 review articles were identified and removed. Additionally, seven cohort studies [20–26] and one case-study [27] were identified and reviewed because they were closely related to our research question, but did not fully match our inclusion criteria (Table 1). The cohort studies mainly described treatment trajectories, behavioral characteristics, disease management strategies, or quality of life among children and youth with T2D; however, they lacked a defined lifestyle intervention or comparator group. Although the identified case-study included a specific lifestyle intervention for one child with T2D, it was excluded based on the nature of the study design. One other study [28] described the evaluation of a community-based program that focused on food preparation skills, but did not include behavioral or clinical outcomes (Table 1). No additional studies were identified through our examination of study reference lists. Contact with experts in the field of pediatric T2D yielded two additional manuscripts, but upon review, these studies did not satisfy our inclusion criteria. In the end, one study (a retrospective, case-control design) met our inclusion criteria [29].

In the study by Willi et al., [29], the use of a very low carbohydrate diet in the treatment of T2D was found be an effective short-term therapy. However, this study was of poor methodological quality and its results should be interpreted with caution. The results are at high risk for bias because it was a convenience sample of hospital-based patients and was not a prospective design with random assignment to treatment and control. This study received a QI score of <11 (rated poor); additional details of this report are described in Table 2.

Discussion

Current treatment guidelines state that children and youth with T2D should receive intensive lifestyle counseling to help them achieve target glycemia within 3 - 6 months following diagnosis [12–16]. Despite this recommendation, our review of the literature revealed only one study that targeted lifestyle modification (diet) as an approach for improving glycemic control in this population. To date, most published studies have either included adults exclusively or have been based on retrospective or cross-sectional cohort studies of boys and girls with insulin resistance, but without T2D. Our review did not reveal any high quality studies that included physical activity interventions to improve short- or long-term glycemic control in children and youth with T2D, nor did it uncover any studies that examined the influence of combining diet and physical activity in the treatment of pediatric T2D. While we identified many review articles concerning the management of T2D in this population, none offered new data regarding the efficacy or effectiveness of lifestyle management for glycemic control.

The lack of published studies of lifestyle management for pediatric T2D may reflect the relatively low prevalence of the disease. Despite some having described pediatric diabetes to be at 'epidemic levels' [30–32], others argue prevalence estimates are of modest concern, even among those populations believed to be at greater risk [33]. Nevertheless, current prevalence estimates of overweight and obesity are cause for concern with respect to the potential for developing T2D and suggest a need for evidence-based recommendations for those who have already been diagnosed and those at high risk.

The Diabetes Prevention Program [7] and other lifestyle interventions for adults at high risk for T2D [8, 9] have provided a model for clinicians and researchers upon which to base the design, delivery, and evaluation of clinical trials for T2D management. Indeed, these studies have informed the design of a recently-launched T2D management trial, which includes a lifestyle component [34]. However, it is important to bear in mind that pediatric and adult populations rarely receive similar therapies in research or clinical settings due to distinct metabolic, physical, developmental, and cognitive differences. Moreover, within the context of pediatric behavior modification, consideration of the complex interrelationships between environmental factors (i.e., family, peers, school, media, built environment) must be taken into account. Therefore, caution must be exercised when generalizing the clinical findings from currently available adult data to the pediatric population.

Of additional importance is the selection of appropriate study outcomes among the pediatric population [35]. Although good glycemic control and healthy body weights are of clinical importance, the antecedents of these clinical outcomes may be more salient [36]. For example, parental interactions with their sons and daughters when making family lifestyle changes have a meaningful impact [37] to the extent that the style with which parents communicate with and set boundaries within their family has considerable influence on children's nutrition and physical activity behaviours [38]. In this regard, evaluating outcomes such as parenting style, self-efficacy, and motivation to change lifestyle behaviours can help to contextualize nutrition and physical activity behaviours as well as metabolic outcomes that are influenced by lifestyle. Moreover, the current evidence-base for weight management may not be a suitable proxy for programs for pediatric T2D since many of the contemporary studies of pediatric weight management have been carried out on pre-adolescent children from primarily Caucasian, middle socioeconomic families. The current cohort of pediatric T2D patients includes (primarily) less affluent families of minority ethnic/racial backgrounds as well as families living with generations of chronic disease and co-morbidities of diabetes for which the disparities in health outcomes are well known in the adult T2D population.

Children and youth with T2D are usually overweight or obese [17]. Current pediatric and adult literature provides good evidence for reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure to enable weight management and reduce the risk of T2D. In adults, however, weight loss is not always necessary to improve glycemic control [39]. Until more evidence is available, it remains unknown whether glycemia can be improved in children and youth with T2D independent of weight loss. However, factors that can impact the achievement and sustainability of healthy lifestyle changes are increasingly being characterized. For example, a comprehensive health assessment prior to intervention enrolment would enable the design of interventions that are tailored to the needs of individuals and families, an advancement that can optimize outcomes in sub-groups with similar features. Weight management interventions that customize treatment based on loss of control eating [40], melanocortin 4 receptor gene mutation [41], maternal mental health [42], and/or motivation [43] could maximize individual responsiveness to weight management therapies. This degree of sophistication represents a substantial improvement beyond traditional variables (i.e., age, gender, obesity status) that, to date, have determined study inclusion and intervention approaches. This would also provide a degree of intervention sophistication that moves beyond a 'one size fits all' for managing T2D.

Presently, the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) is supporting a number of large-scale, multi-centre trials designed to prevent or treat T2D in children and youth under the collaborative titled Studies to Treat Or Prevent Pediatric Type 2 Diabetes (STOPP-T2D). This partnership focuses on treating adolescents already diagnosed with T2D [34] and on the primary prevention of T2D among middle-school aged youth [44]. Unfortunately, following the completion of the NIDDK sponsored trial (Treatment Options for type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth: TODAY) [34], the independent effects of the dietary and physical activity behavioural changes on glycemic control will remain unknown; the trial does not include an independent lifestyle modification arm. Nevertheless, trials such as these are urgently needed to inform clinical practice.

The strengths of this study include the systematic, comprehensive and unbiased approach. The results of our systematic review should however be viewed in light of several limitations. An intrinsic limitation of any systematic review is the potential for publication and selection bias. We acknowledge this methodological drawback and undertook manual searches and contacted recognized experts in pediatric endocrinology. This strategy did not yield any additional unpublished articles that satisfied our inclusion criteria, so it is unlikely that we missed any relevant articles.

Conclusion

In summary, our systematic review indicated that no well-designed studies have evaluated the impact of lifestyle modification on glycemic control in children and youth with T2D. Numerous review articles have been published in this area, but contribute little to our evidence base. Randomized clinical trials must be performed to clearly establish the role of nutrition and physical activity interventions in managing pediatric T2D. These studies might also help to determine the optimal lifestyle treatment approaches for good glycemic control independent of pharmacologic therapy for the pediatric T2D population. We believe that research to examine lifestyle-based therapies, which consider both qualitative and quantitative aspects of nutrition and physical activity in boys and girls with T2D, should remain research and public health priorities.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- HbA1c:

-

glycated hemoglobin

- Kg:

-

kilogram

- L:

-

liter

- m2 :

-

metres squared

- mmol:

-

millimole

- NIDDK:

-

Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- STOPP-T2D:

-

Studies to Treat Or Prevent Pediatric Type 2 Diabetes

- TODAY:

-

Treatment Options for type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth

- T2D:

-

type 2 diabetes

- VLCD:

-

very-low-calorie diet

- QI:

-

quality index

- QOL:

-

quality of life

References

American Diabetes Association: Type 2 Diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2003, 23: 381-389. 10.2337/diacare.23.3.381.

Writing Group for the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group, Dabelea D, Bell RA, D'Agostino RB, Imperatore G, Johansen JM, Linder B, Liu LL, Loots B, Marcovina S, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pettitt DJ, Waitzfelder B: Incidence of diabetes in youth in the United States. JAMA. 2007, 297: 2716-2724. 10.1001/jama.297.24.2716.

SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group, Liese AD, D'Agostino RB, Hamman RF, Kilgo PD, Lawrence JM, Liu LL, Loots B, Linder B, Marcovina S, Rodriguez B, Standiford D, Williams DE: The burden of diabetes among U.S. youth: prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2006, 118: 1510-1518. 10.1542/peds.2006-0690.

Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, Tamborlane WV, Banyas B, Allen K, Savoye M, Rieger V, Taksali S, Barbetta G, Sherwin RS, Caprio S: Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 802-810. 10.1056/NEJMoa012578.

Fagot-Campagna A, Pettitt D, Engelgau M, Burrows N, Geiss L, Gregg E, Williamson D, Venkat Narayan K: Type 2 diabetes among North American adolescents: An epidemiologic health perspective. J Pediatrics. 2000, 136: 664-672. 10.1067/mpd.2000.105141.

Pavkov ME, Bennett PH, Knowler WC, Krakoff J, Sievers ML, Nelson RG: Effect of youth-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus on incidence of end-stage renal disease and mortality in young and middle-aged Pima Indians. JAMA. 2006, 296: 421-426. 10.1001/jama.296.4.421.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 393-403. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, Hu ZX, Lin J, Xiao JZ, Cao HB, Liu PA, Jiang XG, Jiang YY, Wang JP, Zheng H, Zhang H, Bennett PH, Howard BV: Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997, 20: 537-544. 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537.

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M, Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Eng J Med. 2001, 344: 1343-1350. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801.

Look AHEAD Research Group: Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30: 1374-1383. 10.2337/dc07-0048.

Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Hsu RT, Khunti K: Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007, 334: 299-10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55.

American Diabetes Association: Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: Consensus Statement. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23: 381-389. 10.2337/diacare.23.3.381.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33 (s1): S11-S61.

Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee: Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Can J Diabetes. 2008, 32 (s1): S162-S167.

Aslander-van Vliet E, Smart C, Waldron S: ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2006-2007. Nutritional management in childhood and adolescent diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007, 8: 323-339. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00317.x.

Robertson K, Adolfsson P, Riddell MC, Scheiner G, Hanas R: ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2006-2007. Exercise in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008, 9: 65-77. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00362.x.

Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P: Clinical presentation and treatment of type 2 diabetes in children. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007, 8 (S9): 16-27. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00330.x.

Libman I, Arslanian S: Prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes in youth. Horm Res. 2007, 67: 22-34. 10.1159/000095981.

Downs SH, Black N: The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 1998, 52: 377-384. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377.

Zdravkovic V, Daneman D, Hamilton J: Presentation and course of Type 2 Diabetes in youth in a large multi-ethnic city. Diabet Med. 2004, 21: 1144-1148. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01297.x.

Grinstein G, Muzumdar R, Aponte L, Vuguin P, Saenger P, DiMartino-Nardi J: Presentation and 5-year follow-up of type 2 diabetes mellitus in African-American and Caribbean-Hispanic adolescents. Horm Res. 2003, 60: 121-126. 10.1159/000072523.

Zuhri-Yafi MI, Brosnan PG, Hardin DS: Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 15 (s1): 541-546.

Rothman RL, Mulvaney S, Elasy TA, VanderWoude A, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Potter A, Russell WE, Schlundt D: Self-management behaviors, racial disparities, and glycemic control among adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2008, 121: e912-919. 10.1542/peds.2007-1484.

Reinehr T, Schober E, Roth CL, Wiegand S, Holl R: Type 2 Diabetes in children and adolescents in a 2-Year follow-Up: Insufficient adherence to diabetes centers. Horm Res. 2008, 69: 107-113. 10.1159/000111814.

Shield JPH, Lynn R, Wan KC, Haines L, Barrett TG: Management and 1 year outcome for UK children with type 2 diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2009, 94: 206-209. 10.1136/adc.2008.143313.

Allan CL, Flett B, Dean HJ: Quality of life in first nation youth with type 2 diabetes. Matern Child Health J. 2008, 12: S103-S109. 10.1007/s10995-008-0365-x.

Anderson K, Dean H: The effect of diet and exercise on a native youth with poorly controlled non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Beta Release. 1990, 14: 105-106.

Nichol H, Retallack J, Panagiotopoulos C: Cooking for your life! A family-centred, community-based nutrition education program for youth with type 2 diabetes or impaired fasting glucose. Can J Diabetes. 2008, 32: 29-36.

Willi SM, Martin K, Datko FM, Brant BP: Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes in childhood using a very-low-calorie diet. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 348-353. 10.2337/diacare.27.2.348.

Kaufman FR: Type 2 diabetes in children and young adults: a "new epidemic.". Clin Diabetes. 2002, 20: 217-218. 10.2337/diaclin.20.4.217.

Bloomgarden ZT: Type 2 diabetes in the young: the evolving epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 998-1010. 10.2337/diacare.27.4.998.

Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE: Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 1999, 22: 345-354. 10.2337/diacare.22.2.345.

Goran MI, Davis J, Kelly L, Shaibi G, Spruijt-Metz D, Soni SM, Weigensberg M: Low prevalence of pediatric type 2 diabetes: where's the epidemic?. J Pediatr. 2008, 152: 753-755. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.004.

TODAY Study Group, Zeitler P, Epstein L, Grey M, Hirst K, Kaufman F, Tamborlane W, Wilfley D: Treatment options for type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth: a study of the comparative efficacy of metformin alone or in combination with rosiglitazone or lifestyle intervention in adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007, 8: 74-87. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00237.x.

Sinha I, Jones L, Smyth RL, Williamson PR: A systematic review of studies that aim to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials in children. PLoS Med. 2008, 29: 5:e96-

Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Moffett C, Enos G, Infante AM, Krakoff J, Looker HC: Childhood predictors of young-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007, 56: 2964-2972. 10.2337/db06-1639.

Zylke JW, DeAngelis CD: Child and adolescent health--a call for papers. JAMA. 2008, 300: 2062-10.1001/jama.2008.606.

Golan M: Parents as agents of change in childhood obesity - from research to practice. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006, 1: 66-76. 10.1080/17477160600644272.

Norris C, Zhang X, Avenell A, Gregg E, Bowman B, Serdula M, Brown T, Schmid C, Lau J: Long-term effectiveness of lifestyle and behavioral weight loss interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2004, 117: 762-774S. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.024.

Tanofsky-Kraff M, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, Kozlosky M, Schvey NA, Shomaker LB, Salaita C, Yanovski JA: Laboratory assessment of the food intake of children and adolescents with loss of control eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89: 738-745. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26886.

Reinehr T, Hebebrand J, Friedel S, Toschke AM, Brumm H, Biebermann H, Hinney A: Lifestyle intervention in obese children with variations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. Obesity. 2009, 17: 382-389.

Pott W, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pauli-Pott U: Treating childhood obesity: family background variables and the child's success in a weight-control intervention. Int J Eat Disord. 2009, 42: 284-289. 10.1002/eat.20655.

Brennan L, Walkley J, Fraser SF, Greenway K, Wilks R: Motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of adolescent overweight and obesity: study design and methodology. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008, 29: 359-375. 10.1016/j.cct.2007.09.001.

Schneider M, Hall WJ, Hernandez AE, Hindes K, Montez G, Pham T, Rosen L, Sleigh A, Thompson D, Volpe SL, Zeveloff A, Steckler A, HEALTHY Study Group: Rationale, design and methods for process evaluation in the HEALTHY study. Int J Obes. 2009, 33: S60-S67. 10.1038/ijo.2009.118.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/10/97/prepub

Acknowledgements

STJ, MC, JB, and TT-KH received no external support. PWF is supported by Västerbotten's Health Authority (ALF strategic appointment 2006-2009), the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20070633), and the Swedish Diabetes Association (DIA2006-013). ASN is supported by a Career Development Award from the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program (funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [CIHR]). GDCB is supported by a Population Health Investigator Award from Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions and a New Investigator Award from CIHR. These study sponsors did not play any role in this research or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Contents of the publication do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

STJ contributed to study design, data collection, abstraction and interpretation, drafted the first manuscript and made subsequent revisions. ASN conceived the study, made substantial contributions to the study design and made critical revisions of early manuscript versions. MC participated in data collection and data abstraction. JB developed the search strategy and conducted the literature search. TTKH, PWF and MMJ provided critical revisions to the manuscript and provided important intellectual contributions. GDCB conceived the study, helped to solidify the study design and interpretation of data, drafted critical revisions, and, as did all authors, approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, S.T., Newton, A.S., Chopra, M. et al. In search of quality evidence for lifestyle management and glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr 10, 97 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-10-97

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-10-97