Abstract

Background

Our previous studies found the high prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese cancer patients, and many empirical studies have been conducted to evaluate the effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety among Chinese cancer patients. This study aimed to conduct a meta-analysis in order to assess the effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety in Chinese adults with cancer.

Methods

The four most comprehensive Chinese academic database- CNKI, Wanfang, Vip and CBM databases-were searched from their inception until January 2014. PubMed and Web of Science (SCIE) were also searched from their inception until January 2014 without language restrictions, and an internet search was used. Randomized controlled studies assessing the effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer were analyzed. Study selection and appraisal were conducted independently by three authors. The pooled random-effects estimates of standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Moderator analysis (meta-regression and subgroup analysis) was used to explore reasons for heterogeneity.

Results

We retrieved 147 studies (covering 14,039 patients) that reported 253 experimental-control comparisons. The random effects model showed a significant large effect size for depression (SMD = 1.199, p < 0.001; 95% CI = 1.095-1.303) and anxiety (SMD = 1.298, p < 0.001; 95% CI = 1.187-1.408). Cumulative meta-analysis indicated that sufficient evidence had accumulated since 2000–2001 to confirm the statistically significant effectiveness of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety in Chinese cancer patients. Moderating effects were found for caner type, patients’ selection, intervention format and questionnaires used. In studies that included lung cancer, preselected patients with clear signs of depression/anxiety, adopted individual intervention and used State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the effect sizes were larger.

Conclusions

We concluded that psychological interventions in Chinese cancer patients have large effects on depression and anxiety. The findings support that an adequate system should be set up to provide routine psychological interventions for cancer patients in Chinese medical settings. However, because of some clear limitations (heterogeneity and publication bias), these results should be interpreted with caution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

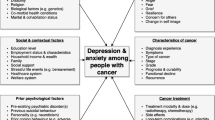

Cancer is considered as a serious and potentially life-threatening illness, and cancer patients have to experience a constellation of challenges, including cancer diagnosis, side effects of medical treatment, sleep disturbance [1], poor adjustment [2], coping strategies [3], emotional distress [4] and problems arising in the family [5]. Therefore, it is well acknowledged that adults diagnosed with cancer are vulnerable to depression and anxiety. In developed countries, such as United States and UK, systemic reviews have indicated that depression and anxiety were two of the common psychological distress in cancer patients [6–9]. Our previous meta-analysis also found that the prevalence of depression (54.90% vs. 17.50%) and anxiety (49.69% vs. 18.37%) were significantly higher in Chinese adults with cancer compared with those without [10]. More seriously, the unrecognized and untreated depression and anxiety could not only lead to difficulty with symptom control, poor compliance with treatment and prolonged recovery time, but also the increased impairment of immune response and impaired quality of life [11–13].

The evidence mentioned above, combined with different national contexts, has led to the increasing interest in psychological interventions in different countries, and cancer patients themselves also reported the need of professional psycho-oncological support [14]. A number of systematic reviews (qualitative and quantitative) have focused on the effectiveness of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety, and psychological interventions, to some extent, have been shown to be effective in reducing depression/anxiety in cancer patients. However, a clear conclusion has not been reached, and the controversy over the effectiveness of psychological interventions still continues. Qualitative review conducted by Newell et al. concluded that no intervention strategy could be recommended for managing depression [15], but Barsevick et al. claimed that psychoeducational interventions were effective for reducing depressive symptoms in cancer patients [16]. Meanwhile, some meta-analyses have provided effect sizes ranging from insignificance [17, 18] to small-medium [19, 20] and small-medium to large [21]. In addition, systematic reviews often focused on either specific type of cancer patients [18] or specific type of intervention [22, 23], which makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions. Recently, Faller et al. pointed out these issues and conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of 198 controlled studies. The results indicated that psycho-oncologic interventions were effective for depression (Cohen’s d = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.25-0.41) and anxiety (Cohen’s d = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.29-0.46) [20].

Although a number of systematic reviews have been conducted to evaluate the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety in adults with cancer, the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety in Chinese cancer patients have still yet not been examined. Conducting such meta-analysis is vitally important for the following reasons. The first reason is attributed to the number of cancer patients in China. The latest data revealed that China had the world’s largest cancer population (new cases and deaths) in 2012. The numbers of new cases and deaths were 3.07 million (21.8% of world total) and 2.20 million (26.9%) [24]. The second reason is due to the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in Chinese adults with cancer. Compared with the prevalence of depression/anxiety among cancer patients in developed countries, our previous meta-analysis found that the prevalence of depression (54.90%) and anxiety (49.69%) was at a high level in China [10]. Third, although the field of psycho-oncology and its related psychological interventions are relatively young in China, intervention studies and narrative reviews are no longer rare. However, there has not been a comprehensive meta-analysis to assess the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety in Chinese adults with cancer. Forth, because most of the results of these intervention studies were published in Chinese journals, they are usually not easily accessed by other countries’ researchers. Finally, a number of Chinese studies about depression/anxiety of cancer patients adopted psychological interventions (such as cognitive-behavioral and psychoeducational therapy) originated in Western countries. It is necessary to explore whether the psychological interventions widely used in Western countries are also effective among Chinese adults with cancer. More importantly, from a clinical point of view, it would be of practical importance for clinicians to evaluate whether psychological interventions, in addition to the medication, not only have positive effects on depression and anxiety, but also have the possibility of improving the use efficiency of Chinese clinical resources.

The aim of the present meta-analysis, therefore, was to quantify the effectiveness of psychological interventions for treatment of depression and anxiety reported in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in Chinese adults with cancer. First, we explored the overall effect size of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety in cancer patients. Second, we examined whether the overall effect size was modified by moderating factors (e.g., intervention type, cancer type, and mean age).

Methods

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted to identify published literature on the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety in Chinese adults with cancer. The CNKI database (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang database, Vip database and CBM database (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database), which are the four most comprehensive Chinese academic databases, were searched from their inception until January 2014. We used ‘depression or depressive disorders or depressive symptoms’ and ‘anxiety or anxiety disorder or anxiety symptoms’ and ‘cancer or oncology or malignant neoplasm or malignant tumor’ combined with ‘psychological intervention or psychological treatment or psychotherapy’ as search themes in the article titles, abstracts and keywords. The reference lists of relevant articles obtained were also screened.

In order to expand searches, PubMed and Web of Science (SCIE) were searched from their inception until January 2014 without language restrictions, and an internet search was also used (e.g., http://www.google.com). The search strategy was: (psychotherapy [MeSH Terms] OR psychotherapy [Title/Abstract] OR psychological therapy [Title/Abstract] OR psychiatric counseling [Title/Abstract] OR psychological intervention [Title/Abstract] OR psychological treatment [Title/Abstract]) AND (neoplasms [MeSH Terms] OR cancer [Title/Abstract] OR neoplasms [Title/Abstract] OR oncology [Title/Abstract]) AND (China [MeSH Terms] OR China or Mainland China [Title/Abstract]) AND (depression [MeSH Terms] OR depressive disorder [MeSH Terms] OR depression [Title/Abstract] OR depressive disorder [Title/Abstract] OR depressive symptoms [Title/Abstract] OR anxiety [MeSH Terms] OR anxiety disorders [MeSH Terms] OR anxiety [Title/Abstract] OR anxiety disorders [Title/Abstract] OR anxiety symptoms [Title/Abstract]).

The screening of the abstracts/titles and full-text articles were performed twice by three authors (YLY, GYS, GCL) independently to reduce reviewer bias and errors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all studies in which: (1) the subjects were aged 16 or older; (2) RCTs were eligible, including experimental group and control group; (3) the subjects were patients diagnosed with cancer; (4) studies were included to those involving more than 30 adults with cancer; (5) a psychological intervention in experimental group was compared to a control group; (6) depression and anxiety were evaluated by well-validated measures, such as clinical diagnosis and self-report questionnaires that previous studies have established the reliability and validity of them as a measure of depression/anxiety at home and abroad; (7) the subjects were from Mainland China (Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao were excluded due to the long-term influence of foreign culture). We excluded studies in which: (1) the description of psychological interventions was not set forth so clearly in the Method section that other researchers could not duplicate or refer to such studies to conduct psychological interventions; (2) studies in which insufficient data were available to calculate effect sizes were excluded; (3) studies including non-psychological interventions, such as physiotherapy, physical training, and medicine interventions were excluded; (4) Hospice and terminal home care were excluded because they might be distinct from psychological interventions; (5) studies using dimension scores to evaluate depression/anxiety (e.g., depression and anxiety dimension scores of SCL-90) were excluded. Eligibility judgment and data extraction were recorded and carried out independently by two authors (YLY and GYS) in a standardized manner. Any disagreements with them were resolved by discussion and the involvement of another author (LW).

Quality assessment

Although many scales are used to evaluate the methodological quality of RCTs, none can provide an adequately and comprehensively reliable assessment [25]. A systematic review indicated that Jadad scale presented the best validity and reliability evidence compared with other scales [25], but Jadad scale only including 3 items [26] may be too simple to well assess quality of RCTs in our meta-analysis. Therefore, the modified Jadad scale for assessing quality of RCTs was adapted for use [27]. The modified Jadad scale is an eight-item scale designed to assess randomization, blinding, withdrawals/dropouts, inclusion/exclusion criteria, adverse effects, and statistical analysis. In this meta-analysis, blinding (2 points) and adverse effects (1 point) were excluded, because blinding is often not feasible for trials of psychological interventions, and psychological interventions usually has few negative side effects. As a result, the score for each study can range from 0 (lowest quality) to 5 (highest quality).We defined three categories: the study was considered to have high quality (low risk of bias) if it scored 4 points or above, studies that scored 1 point or below were categorized as having low quality (high risk of bias), studies that scored 2 points or 3 points were considered as having medium quality (moderate risk of bias). Any disagreements with authors (GCL and SMW) were resolved by discussion and the involvement of another author (LW).

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction scheme was developed and pilot tested on 5 included studies. For all studies, two authors independently extracted data (DSH and SMW). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. In situations where the coder was unsure, one of the authors was consulted until consensus was reached.

Data extracted from the present study included author name, year of publication, age range and mean age, simple size, outcomes (depression and anxiety) and assessment instruments (clinical diagnosis/self-report), selection of participants by the clear signs of depression/anxiety, cancer type, cancer stage, intervention type (cognitive-behavioral interventions (CBT), patients education (PE), relaxation/imagery, social/family support, music therapy, nursing intervention, other), professionalism of therapists (e.g., nurse, doctor, and psychologist), intervention format (individual, group, family), information about treatments and timing of assessment, and mean and standard deviation (SD) of each study.

Among these types of interventions, the seven categories were defined as follows. CBT included cognitive, cognitive-behavioral, and behavioral methods focused on changing specific thoughts or behaviors or on learning specific coping skills. PE (or called information and counseling) included interventions primarily providing health education (procedural or medical information), coping skills training, stress management, and psychological support. If interventions mainly focused on coping skills or psychological support, these were classified as “CBT” or “social/family support”. Relaxation and imagery techniques were any method, process, or activity that helped patients to relax and attain a state of calmness. Social/family support referred to nonprofessionally/professionally guided support groups (social support) or to the patients’ family members (family support) that provided mutual help and support (e.g., emotional support, financial support, and the communication of shared experiences). Music therapy referred to an interpersonal process in which the therapist used music and all of its facets (physical, emotional, social, and aesthetic) to help patients to improve or maintain their health, and it should be different from “relaxation/imagery” when conducted as the only intervention. Nursing intervention were the actions undertaken by caregivers (mainly nurse) to adopt nonspecific interventions to further provide a high level of care, such as promoting communication with patients and their families, understanding, encouraging and comforting patients, strengthening nursing care, and providing suitable environment. If interventions aimed at emotional support and emotional release, these were classified as “social/family support” or “relaxation/imagery”. Interventions not matching these definitions were classified as “other”.

Meta-analysis

Assessment of overall effect size

We computed the effect size of standardized mean difference (SMD) for each study by subtracting the average post-test score of the control group from that of the experimental group and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviations of the experimental group and control group. Means and standard deviations of depression/anxiety were used for computation of SMD (Cohen’s d). A SMD of 1 indicates a relatively stronger improvement in experimental group by one standard deviation larger than the mean of the control group. For a certain outcome, only one effect size per study was included. If an experimental-control comparison provided more than one effect size for depression/anxiety, the results were averaged. The pooled random-effects estimates of SMD and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as the summary measure of effect. A random effects model was used because it involves the assumption of statistical heterogeneity between studies [28]. Effect sizes of 0.80 are regarded as large, while effect sizes of 0.50 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0.2 are small [29]. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant. Overall effects were analyzed using the statistical software Stata v11.0.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was evaluated with the Q statistic and I2 statistic. The Q statistic is used to assess whether differences in results are compatible with chance alone. If the P value of Q statistic is above 0.05, it indicates that there is no significant heterogeneity, but the Q statistic is sensitive to the number of studies [30]. To complement the Q statistics, the I2 statistic which denotes the variance among studies as a proportion of the total variance was also calculated and reported, because I2 is not sensitive to the number of studies [30]. Larger values of I2 show increasing heterogeneity. An I2 of 0% shows no observed heterogeneity, while 25% shows low, 50% moderate, and 75% high levels of heterogeneity [31].

Moderator analyses

When the hypothesis of homogeneity was rejected by the Q statistic and I2 statistic, meta-regression (continuous variable) and subgroup analysis (categorical variable) were conducted in order to explore the potential moderating factors for heterogeneity [30]. In our study, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were conducted for moderating factors, including cancer type, cancer stage (early vs. advanced stage), patients’ selection (clear signs of depression/anxiety vs. regardless of depression/anxiety level), patients’ age, simple size, quality of study, intervention type (CBT, PE, relaxation/imagery, social/family support, music therapy, nursing intervention, other), intervention format (individual vs. other formats), appropriate randomization (yes/no), the used questionnaires and timing of assessment. Because most of studies in our meta-analysis included more than one type of intervention, intervention type was not considered as a categorical variable, and the sum types of intervention was the indicator of intervention type.

Assessment of publication bias

The potential of publication bias of the included studies was first examined by funnel plot symmetry. A funnel plot is a useful graph designed to check the existence of publication bias in meta-analyses. A symmetric funnel shape indicates that publication bias is unlikely, but an asymmetric funnel suggests the possibility of publication bias. However, some authors have argued that visual interpretation of funnel plots is too subjective to be useful [32]. So Begg’s test and Egger’s test were further used to more objectively test for its presence (as implemented in Stata v11) [33, 34].

Cumulative meta-analysis

We explored the evolution of evidence of the effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety among Chinese cancer patients over time using cumulative meta-analysis [35]. Studies were sequentially accumulated by year they first became available (e.g., publication in a journal) to a random-effects model using the “metacum” user-written command in Stata v 11.

Results

Study selection

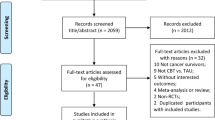

A flowchart describing the inclusion and exclusion process was presented. As shown in Figure 1, we identified the possibly eligible articles through CNKI database (n = 585), Wangfang database (n = 575), Vip database (n = 430) and CBM database (n = 542). The titles and abstracts of these articles were respectively studied by the three authors (YLY, GYS and GCL), and the full-text articles without duplicates (n = 738) were selected for further examination. Based on the full-text of these 738 studies, 595 did not meet the inclusion criteria as documented in Figure 1. In total, 143 studies reporting on 247 experimental-control comparisons (Depression: n = 119; Anxiety: n = 128) were included in the present meta-analysis [36–178].

In order to expand searches, we also searched the international databases of PubMed, SCIE (as shown in Figure 2), and an internet search (e.g., http://www.google.com). There were 4 studies from PubMed that met our inclusion criteria through the international databases search [179–182].

Selection process of studies for the meta-analysis (international databases). Abbreviations: RCTs, randomized controlled trials; SCIE, Web of Science. *Records could not be identified through the original search strategy, and “China [MeSH] OR China [Title/Abstract] or Mainland China [Title/Abstract]” was excluded from the original search strategy.

Characteristics of included studies

Study characteristics were listed in Table 1. The studies of this meta-analysis, including 133 journal articles and 14 dissertations, were published from 2000 to 2013. The studies comprised 14,039 subjects. The mean sample size was 95.5 (median: 80; range: 30–326). Subjects had a mean age of 52.4 years (median: 51.9; range: 39–74). Depression and anxiety were assessed by clinical diagnosis in 16 studies [37, 42, 47, 48, 58, 83, 101, 102, 107, 108, 113, 127, 132, 144, 146, 181], while that of the other studies was assessed by self-report questionnaires like Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). For a certain outcome, each study only included one effect size. Only 15% of studies preselected patients according to their clear signs of depression/anxiety. Forty-six percent included mixed cancer diagnoses, and 15% included breast cancer and gynaecological cancer, respectively. Seventeen percent of studies included advanced cancer patients, and 6% included early cancer patients. PE (74%) was the most common intervention type used, and the proportion on the order was social/family support (63%), CBT (54%), relaxation/imagery (54%), nursing intervention (52%), music therapy (14%), and other interventions (14%). Therapists included nurses (46%), doctor and oncologist (14%), psychologists (11%), and others. Finally, 21% of studies only employed the individual (i.e., one-on-one) intervention format and 68% clearly provided the information about treatments.

Risk of bias assessment

Ratings of study quality for each criteria of the modified Jadad were presented in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, higher scores reflected the better study quality, and the average scores of all studies were above 2 (mean: 2.68). Nineteen studies were judged to have low quality for random sampling or withdrawals/dropouts or inclusion/exclusion criteria or the statistical analysis and twenty-seven of high quality. Other studies were rated as medium quality.

Effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety in cancer patients

A pooled random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using data from 147 studies, which estimated the post-test effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety compared with care-as-usual control group. This meta-analysis included data for 7,181 patients in the experimental group, and 6,858 patients in the control group. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, the random effects model showed an overall effect size of SMD = 1.199 (95% CI = 1.095-1.303; p < 0.001) for depression in 122 studies, and a large effect size was also observed (SMD = 1.298, 95% CI = 1.187-1.408; p < 0.001) for anxiety in 131 studies. However, the heterogeneity analysis of the effect sizes of depression (Q = 787.21, p < 0.001; I2 = 84.6%) and anxiety (Q = 1016.74, p < 0.001; I2 = 87.2%) indicated that there was a relatively high amount of heterogeneity in our meta-analysis.

Forest plot of the effects of psychological interventions on depression in cancer patients. It shows a pooled SMD of 1.199 (95% CI = 1.095-1.303; p < 0.001), indicating that psychological interventions could alleviate depression among Chinese adults with cancer. Abbreviations: SMD, standardized mean difference.

Forest plot of the effects of psychological interventions on anxiety in cancer patients. It shows a pooled SMD of 1.298 (95% CI = 1.187-1.408; p < 0.001), indicating that psychological interventions could alleviate anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer. Abbreviations: SMD, standardized mean difference.

Moderator analysis

In univariate and multiple meta-regressions analysis (in Additional files 1 and 2), no moderating effects were found for patients’ age, simple size, intervention type and quality of study (p > 0.05). As shown in Table 3, within the subgroup of studies evaluating moderator variables, significant effects of cancer type were found for depression (p < 0.001) and anxiety (p = 0.02). Effect size in patients with lung cancer was the largest (Depression: SMD = 1.481, 95% CI = 0.811-2.151; Anxiety: SMD = 1.588, 95% CI = 0.994-2.182), but among patients with breast patients, it was the smallest (Depression: SMD = 1.106, 95% CI = 0.830-1.382; Anxiety: SMD = 1.153, 95% CI = 0.857-1.448). Compared with the unselected patients (SMD = 1.170, 95% CI = 1.058-1.282), the effects of psychological interventions on depression were larger (SMD = 1.368, 95% CI = 1.095-1.642) in cancer patients with clear signs of depression/anxiety. Individual psychotherapy (SMD = 1.575, 95% CI = 1.266-1.884) showed a larger effect size on anxiety than the other intervention formats did (SMD = 1.161, 95% CI = 1.045-1.276), and the effect size was the largest in the studies using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to assess anxiety among cancer patients (SMD = 1.800, 95% CI = 0.717-2.884).

Publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated some publication bias, and the Begg’s test and Egger’s test further suggested the publication bias in depression (Begg’s test, Z = 4.16, P < 0.001; Egger’s test, Coef = 3.659, P < 0.001) and anxiety (Begg’s test, Z = 4.99, P < 0.001; Egger’s test, Coef = 4.469, P < 0.001) in our meta-analysis.

Cumulative meta-analysis

Cumulative meta-analysis (Figure 5) indicated that the protective effects of psychological interventions on depression became evident in 2000. Since 2012, the overall effect size (SMD) has remained relatively stable (range: 1.15 - 1.21), and subsequent studies published in 2013 hardly changed the overall effect size. The protective effects of psychological interventions on anxiety became evident in 2001 (Figure 6). Sufficient body of RCTs had accumulated by 2003 to determine a reliable and consistent point estimate (fluctuated around 1.3), and resulted in a narrowing of the 95% CI.

Discussion

At the beginning of discussion, we would evaluate the heterogeneity and study quality in the present meta-analysis. First, we performed strict inclusion criteria, random effects models and moderator analysis to control and reduce the heterogeneity. However, the heterogeneity was still relatively high, and the conclusion should be considered with some caution. Second, the modified Jadad scale was used to assess the study quality. Although most of the included studies (87%) had medium-quality or high-quality, studies in our meta-analysis had the high bias of the inappropriate methods of randomization (79%) and the lack of description of withdrawals/dropouts (88%). Quality assessment indicated these methodological weaknesses, which could weaken the internal validity.

In the present meta-analysis, we analyzed the effects of psychological interventions on depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer. To our knowledge, this is the largest and the most comprehensive meta-analysis studying the effects of psychological interventions on psychological distress in Chinese adults with cancer, and psychological interventions were proven effective to relieve cancer patients’ depression (SMD = 1.199, 95% CI = 1.095-1.303) and anxiety (SMD = 1.298, 95% CI = 1.187-1.408) in our meta-analysis. Although the research of psychological interventions in cancer patients is quite common, the large and comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by foreign researchers usually excluded Chinese studies because they were published in a foreign language [20]. Some Chinese meta-analysis in this field only included only a small number of studies (n = 11) [183, 184], which did not accurately reflect the current research of psychological interventions in Chinese cancer patients. On the other hand, the results of cumulative meta-analysis showed that the protective effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety were evident from 2000–2001 onwards. Subsequent included studies have only tried to increase the precision and reliability of effectiveness of psychological interventions in Chinese adults with cancer, and the overall effect size was both substantial and unlikely to be changed by the further RCTs evidence.

We also compared our results with three other relatively comprehensive meta-analyses exploring the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety in cancer patients: (1) the study of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer conducted by Faller (Depression: n = 72, Cohen’s d = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.25-0.41; Anxiety: n = 74, Cohen’s d = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.29-0.46) [20]; (2) the research of the effects of psychological interventions on anxiety/depression in cancer patients reported by Sheard (Depression: n = 20, effect size = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.06-0.66; Anxiety: n = 19, effect size = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.08-0.74) [19]; (3) the review of psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients conducted by Galway (Depression: n = 6, SMD = 0.12, 95% CI = −0.07-0.31; Anxiety: n = 4, SMD = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.13-0.22) [17]. There might be several reasons for the different effect sizes. The first explanation might be that nearly half of the included studies in our meta-analysis (48%) adopted the psychosocial interventions targeting at both patient and their family members (this percentage in Faller’s study [20] is 4%). Psychosocial interventions involving family members have been proven to be beneficial for depression of chronic illness patients, including cancer patients [185]. Moreover, family is the bedrock of Chinese society, and the care and concern of family members are of great importance for cancer patients. Second, most of the included studies of these meta-analyses are from developed countries and have lower prevalence of mental health problems as compared to developing countries like China [186], and our previous studies also found that the prevalence of depression/anxiety was very high among Chinese cancer patients [10, 187]. Psychological interventions on depression and anxiety were generally highly effective when psychological distress was at a high level at baseline [188]. Third, with the exception of one study of outpatients in non-hospital setting [74], all of the patients in our study were inpatients who had adequate time and appropriate locations to receive psychological interventions (this percentage of inpatients in Faller’s study [20] is 16%), thus with a reduced risk for drop-out. Studies on the issues of compliance/dropout claimed that drop-out rate was an important indicator of therapeutic effectiveness [189]. Therefore, the large effect size in our study may be due to the reduced risk of drop-out. The last explanation might be that these three meta-analyses mainly included breast cancer patients (Faller’s study: 39% [20]; Galway’s study: 30% [17]). Our meta-analysis found that the effect of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety was the smallest among breast cancer patients (this percentage in our study was 15%), and this might also inflate the overall effect sizes.

In the present meta-analysis, no moderating effect was found for intervention type (continuous variable) in univariate and multiple meta-regressions analysis. Similar to the results of our meta-analysis, most of psychological interventions in other comprehensive meta-analyses were integrative [17, 19, 20], so it could be difficult to compare the effects of different psychotherapies. However, significant medium-to-large effects were observed for the meta-analyses focusing on the separate psychological interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based therapy, relaxation/imagery, and CBT) [21–23], indicating that the quality and content of psychological interventions could be more important for cancer patients than the total types of included interventions.

Through the subgroups analysis of moderator variables (categorical variable), significant moderator effects were found for cancer type, patients’ selection, intervention format and questionnaires employed. The order of the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety was lung cancer, head/neck cancer, digestive tract/gynecological cancer and breast cancer among different types of cancer. The epidemiological features and the psychosocial problems of the specific types of cancer might be the leading cause of this result. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in China and the world [24, 190], and lung cancer patients were at higher risk for psychosocial problems (e.g., stigma and depression) [191, 192]. For example, lung cancer patients experienced the greatest amount of psychological distress among 14 types of cancer [193]. Head/neck and gynecological cancer patients also experienced the unique stress and psychological problems. Patients had to face stigma, functional impairment and disfigurement caused by the cancer and/or the treatment [191, 194], and gynecological cancer patients had problems including stigma, self-image, female fertility, and changes in sexual function [187, 191]. However, in China, the death rate of breast cancer was at a medium or low level (ranked as the fifth following lung cancer and digestive tract cancer) [190], and survival rates have increased to the extent that more than 70% now survived 5 years after diagnosis in urban areas [195]. In a large cancer cohort, higher rates of mixed anxiety/depression symptoms were found in patients with digestive tract, head/neck, and lung cancers, while lower rates were observed in those with breast cancers [196]. As a result, compared with breast cancer patients, other types of cancer patients might have a higher level of psychological distress, and the effects of psychological interventions on depression/anxiety were larger in patients with lung, head/neck, digestive tract, and gynecological cancers [188].

Effect sizes of patients with clear signs of depression/anxiety were significantly larger for depression, and individually based interventions were more effective for anxiety than those delivered in other formats. Psychological interventions appeared to be more useful for patients with increased psychological distress, which was similar to the findings of other meta-analyses in this field [17, 19, 20], indicating that compared with non-screened patients, patients with clear signs of psychological distress could benefit more from psychological interventions, and the effects of interventions targeted at those at risk of psychological distress would be much larger. Additionally, individual interventions appeared to be more effective for anxiety in our meta-analysis, indicating that individual therapy could be more suitable for anxiety among cancer patients. Individual interventions were better suited to handle particular, individual and internal problems [197], and to some extent, anxiety is a normal and individual reaction when a person is faced with different stressors, including cancer [10, 187]. Therefore, individual interventions might be more helpful to deal with the anxiety caused by different types of cancer. However, some studies reported the conflicting results [19, 21, 198], and more studies are needed to confirm whether the effects of psychotherapy on psychological distress are affected by intervention format. Finally, in addition to considering these moderator effects, it is also important to evaluate the influence of different kinds of questionnaires employed on the outcomes of psychological interventions among cancer patients.

Implication

There are several theoretical and practical implications for our meta-analysis. In theory, although cultural traditions, life experience, social economy and ideology were different between China and Western countries, the present meta-analysis suggested that the psychological interventions (or psychotherapies) widely used in Western countries are also suitable and even more efficacious in Eastern culture context. In practice, first, some developed countries, such as United States and Australia, have developed several clinical practice guidelines for the psychotherapy and supportive care of cancer patients [199], but the corresponding management systems and processes are still not available in China. Therefore, the Chinese government and Chinese medical settings should set up an adequate institutional and organizational system to provide routine use of psychological interventions in cancer patients; second, when interventions are performed, quality and content of interventions might be more important for cancer patients than the total types of included interventions, and further studies should be conducted to explore whether psychological interventions involving family members will be more effective for depression/anxiety in cancer patients; third, our findings also provided guidance in developing optimal methods and appropriate standards of psychological interventions in clinical practice. For example, oncologists and physicians should pay more attention to detecting depression/anxiety of specific types of cancer (e.g., lung cancer), and necessary and timely psychological interventions should be taken to alleviate depression/anxiety in these cancer patients. Moreover, psychotherapeutic programs should screen and preselect patients with clear signs of depression/anxiety, so that the limited clinical resources in China could be appropriately allocated and produce maximal cost-effectiveness and clinical benefits.

Limitation

The present meta-analysis had several limitations. First, our meta-analysis did not provide enough information and number of studies regarding other potential moderating factors, such as gender, income, intervention sessions and duration, and metastasis. Second, although we employed moderator analysis to explore potential sources of heterogeneity, the moderator analysis could not reduce I2 to 75% or less in many cases. This may be mainly because interventions in our meta-analysis varied greatly with respect to intervention type and professionalism of therapists, and other important moderating factors. Third, most of the included studies were conducted using self-rating questionnaires (e.g., SAS and SDS) to measure depression and anxiety. Therefore, depression and anxiety in our meta-analysis more often referred to the depressive symptom and anxiety symptom. Fourth, because follow-up results after post-test were not reported, it is not confirmed whether there were long term effects. Fifth, unpublished researches were not included in our meta-analysis, and unpublished outcomes were often insignificant, which might inflate the effect sizes in the presented study. Finally, the high risk of publication bias is another (and perhaps the most important) limitation. This might be mainly because unlike some foreign medical journals that require registration of a trial before it commences, the systems related to registries have not yet been established in China. Thus, attempts to identify unpublished studies are very difficult.

Conclusions

Although there are some clear limitations (heterogeneity and publication bias) in this study, a tentative and preliminary conclusion can be reached, that psychological interventions of depression and anxiety are effective for Chinese cancer patients. In studies that included lung cancer, preselected patients with clear signs of depression/anxiety, adopted individual intervention and used STAI, the effect sizes are larger. The findings support that an adequate system should be set up to provide routine psychological interventions for cancer patients in Chinese medical settings.

References

Palesh OG, Collie K, Batiuchok D, Tilston J, Koopman C, Perlis ML, Butler LD, Carlson R, Spiegel D: A longitudinal study of depression, pain, and stress as predictors of sleep disturbance among women with metastatic breast cancer. Biol Psychol. 2007, 75: 37-44. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.11.002.

Ma JLC: Factors influencing adjustment of patients suffering from nasopharynx carcinoma-implications for oncology social work. Soc Work Health Care. 1997, 25: 83-103. 10.1300/J010v25n04_06.

Lauver DR, Connolly-Nelson K, Vang P: Stressors and coping strategies among female cancer survivors after treatments. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30: 101-111. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000265003.56817.2c.

Bultz BD, Carlson LE: Emotional distress: the sixth vital sign-future directions in cancer care. Psychooncology. 2006, 15: 93-95. 10.1002/pon.1022.

Keir ST, Swartz JJ, Friedman HS: Stress and long-term survivors of brain cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007, 15: 1423-1428. 10.1007/s00520-007-0292-1.

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N: Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12: 160-174. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X.

Massie MJ: Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004, 32: 57-71.

Van’t Spijker A, Trijsburg RW, Duivenvoorden HJ: Psychological sequelae of cancer diagnosis: a meta-analytical review of 58 studies after 1980. Psychosom Med. 1997, 59: 280-293. 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00011.

Stark DP, House A: Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2000, 83: 1261-1267. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1405.

Yang YL, Liu L, Wang Y, Wu H, Yang XS, Wang JN, Wang L: The prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013, 13: 393-10.1186/1471-2407-13-393.

Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, Ly KL: Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review. Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliat Med. 2002, 16: 81-97. 10.1191/02169216302pm507oa.

Miller K, Massie MJ: Depression and anxiety. Cancer J. 2006, 12: 388-397. 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00008.

Reiche EMV, Nunes SOV, Morimoto HK: Stress, depression, the immune system and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004, 5: 617-625. 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01597-9.

Goerling U, Odebrecht S, Schiller G, Schlag PM: Need for psychosocial care in in-patients with tumour disease. Investigations conducted in a clinic specializing in tumour surgery. Chirurg. 2006, 77: 41-46. 10.1007/s00104-005-1094-y.

Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ: Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: Overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002, 94: 558-584. 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558.

Barsevick AM, Sweeney C, Haney E, Chung E: A systematic qualitative analysis of psychoeducational interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002, 29: 73-84. 10.1188/02.ONF.73-87.

Galway K, Black A, Cantwell M, Cardwell CR, Mills M, Donnelly M: Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 11: CD007064-

Semple C, Parahoo K, Norman A, McCaughan E, Humphris G, Mills M: Psychosocial interventions for patients with head and neck cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 7: CD009441-

Sheard T, Maguire P: The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta-analyses. Br J Cancer. 1999, 80: 1770-1780. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596.

Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R: Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31: 782-793. 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922.

Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M: Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006, 36: 13-34. 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L.

Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D: The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010, 78: 169-183.

Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M: The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical review. Psychooncology. 2001, 10: 490-502. 10.1002/pon.537.

Stewart BW, Wild CP: World Cancer Report 2014. 2014, Switzerland: WHO Press

Olivo SA, Macedo LG, Gadotti IC, Fuentes J, Stanton T, Magee DJ: Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2008, 88: 156-175. 10.2522/ptj.20070147.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y: Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001, 12: 232-236. 10.1159/000051263.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Cohen J: A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992, 112: 155-159.

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H: Introduction to meta-analysis. 2009, Oxford: Wiley

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327: 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J: In an empirical evaluation of the funnel plot, researchers could not visually identify publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 894-901. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.006.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M: Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994, 50: 1088-1101. 10.2307/2533446.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315: 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Lau J, Antman EM, Jimenez-Silva J, Kupelnick B, Mosteler F, Chalmers TC: Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327: 248-254. 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406.

Zhu HY, Deng SH, Zhang P, Li DZ: Effect of PDCA circulation in psychological intervention on anxiety and depression of patients with lung cancer. J Clinical Res. 2013, 30: 1324-1326. (in China)

Wang DS, LI GL, Chen JH, Liu XM: Effects of psychological interventions in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Chinese J Clinical Psychology. 2011, 19: 561-563. (in China)

Zhong TP, Zheng HJ, Zhu R: A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Guangdong Medical J. 2003, 24: 57-58. (in China)

Wang GF, Shi YG, Ma GL, Han X, Tian AL: Preliminary approach to the therapy of relaxative imagination and subconscious music revulsion supplemented to radio therapy on cancer. J Henan Medical College for Staff and Workers. 2000, 12: 3-5. (in China)

Xu XR: Health education and psychological nursing in cancer patients after surgery. Guide of China Medicine. 2010, 8: 134-136. (in China)

Liu LJ, Liu JH, Li JJ: Effects of psychological interventions among cancer patients. Medical Information. 2011, 24: 444-445. (in China)

Yang LZ, Mao WQ, Hou AZ, Xie CG, He Y, Cao CS: A comparative study of group mental interference on cancer patients in recovery period. China J Cancer Prevention and Treatment. 2002, 9: 452-453. (in China)

Liu AM, Gan XL: Effect of background music on psychological state of malignant tumor patients under radionuclide bone imaging. J Luzhou Medical College. 2013, 36: 401-403. (in China)

Lian XH, Cao KJ, He ZM, Chen ZM, Qin HY, Xian MC: Clinical study on psychological nursing of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma undergoing radiotherapy. Chin Nurs Res. 2003, 17: 65-67. (in China)

Cheng H, Zhang H, Liu XY: Effects of comprehensive psychotherapy on nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Cancer Research and Clinic. 2010, 22: 554-556. (in China)

Liu QF, Sun GM, An Y, Qin YX: Effects of short-term psychological intervention on depression and anxiety among cancer patients in perioperative period. Medical Information. 2010, 5: 704-705. (in China)

Wu XR, Dong JW: Study on psychological nursing care of malignant tumor patients complicated with anxiety or depression. Chin Nurs Res. 2011, 25: 54-55. (in China)

Liu JH: Mental nursing intervention for patients with malignant tumors. China Medical Herald. 2012, 9: 125-126. (in China)

Jiang WJ, Liu YD, Hou W: Effect of relax training on the psychological status and quality of life in patients undergoing partial laryngectomy. Chinese J Nursing Education. 2012, 9: 27-29. (in China)

Qian AH, Cai CP: Psychological nursing intervention on patients with gynecology malignant tumor undergoing chemotherapy. J Practical Oncology. 2007, 21: 596-598. (in China)

Chen J: Psychological status, quality of life and related psychological intervention in patients with gynecological malignancies. West China Medical J. 2012, 27: 259-261. (in China)

Liu L, Lin XH, Zhao YM, He XX, Li GY: The psychological aspects of patient of gynecological malignant tumor after operation and the effects of psychological nursing in these patients. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2008, 23: 157-158. (in China)

Wang HF: Psychological care among patients with gynecological malignancies. Chinese Community Doctors. 2013, 15: 340-(in China)

Huang LL, Su XN, Shi KF, Wang XL: Effects of individual psychological intervention on negative emotion of cancer patients before surgery. J Qilu Nursing. 2008, 14: 27-28. (in China)

Feng JX: Effects of individual nursing intervention on anxious emotion of breast cancer patients during surgery. Chinese J Clinical Rational Drug Use. 2012, 5: 133-134. (in China)

Ye S: Effects of nursing intervention on anxiety of patients with gynecological malignancies during surgery in perioperative period. Medical Information. 2011, 24: 4809-4810. (in China)

Liu QT, Shao Y, Bi XX: Effect of nursing intervention on the psychology and quality of life in radiotherapy for patients with bone metastases. Hainan Medical J. 2013, 24: 2331-2333. (in China)

Zheng YQ: Effects of nursing intervention plus paroxetine on depression, anxiety and quality of life in cancer patients. J Qiqihar University of Medicine. 2012, 33: 517-518. (in China)

Wu MH, Chen XH, Liu AQ, Wu YY, He XH: A clinical study on psychological nursing intervention to improve psychological status of patients with advanced cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Chinese J Clinical Oncology and Rehabilitation. 2007, 14: 85-87. (in China)

Sun MJ, Ding FM, Zang L: Effect of psychological intervention on negative emotions of cancer patients during chemotherapy. China Medical Herald. 2012, 9: 136-137. (in China)

Du LN, Wang GH, Cheng Y, Liu Y, Yuan L, Zheng SM: Active cognition-behavior therapy of breast cancer chemotherapy patients’ psychological status and the influence on the quality of life. Chinese J Modern Nursing. 2011, 17: 3249-3252. (in China)

Hu JE, Yan Y: Application and effect of group psychotherapy in patients with cancer. China Medical Herald. 2011, 8: 55-57. (in China)

Li JN, Tang HY, Fu HL: Effects of structural group psychotherapy to the mood and QOL in thyroid cancer radionuclear therapy patients. China J Health Psychology. 2009, 17: 243-245. (in China)

Shen BY, Liu JW, Liu S: Impact of the individualized whole period nursing care on the perioperative psychological status of cancer patients. J Qilu Nursing. 2011, 17: 13-14. (in China)

Zhu ML, Wang CJ, Xie L, Li HF: Psychological intervention on depression of elderly patients with digestive cancer. Chinese J Postgraduates of Medicine. 2011, 34: 60-61. (in China)

Yang ZX: Nursing intervention on depression state of elderly patients with digestive tumor. Chinese J Practical Nursing. 2012, 28: 69-70. (in China)

Cao WB, Li P: The effect of psychological interventions on mood of cancer patients. China J Health Psychology. 2011, 19: 1433-1434. (in China)

Zhu J, Hu JE: Application of strengthened psychological intervention in depression and anxiety of radical resection for gynecological malignancies. International J Nursing. 2012, 31: 2348-2349. (in China)

Wen XX, Liang SM: Psychological characteristics and psychological intervention of young patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Modern Preventive Medicine. 2007, 34: 331-333. (in China)

Yang H, Yuan W, Liu XL, Huang Y: Effect of psychological intervention on malignant tumor patients treated with whole body thermotherapy. Foreign Medical Science Section of Medgeography. 2012, 33: 203-206. (in China)

Guo YS, Lai YG, Zhong JY, Liu JX, Guo YW, Wu DY: Cognitive therapy on patients with malignant tumor common clinical observation. Chinese J Medical Guide. 2010, 12: 2052-2053. (in China)

Li XR, Xia D, Xu LX, Yu H: Pre-operative psychological analysis and post-operative psychological intervention in patients with breast cancer. China Modern Medicine. 2012, 19: 102-105. (in China)

Yang YL, Zhao GZ, Xiong Y, Li L: Clinical effective observation on psychological therapy in patients with breast cancer. J Modern Medicine & Health. 2012, 28: 664-665. (in China)

Du LH: Community-based interventions on gynecologic malignancy patients with psychological and pain effect. China Health Care & Nutrition. 2013, 23: 4395-(in China)

Wang HF, Niu ME, Jin MJ, Meng HY, Li M: Contrasted study of supportive group psychotherapy for 68 patients with advanced cancer. J Nurses Training. 2006, 21: 583-585. (in China)

Li Z, Zhang HM, Zhang HY: Psychological intervention on mental health of perioperative patients with cancers. Chin Ment Health J. 2002, 16: 147-148. (in China)

Lv XZ, Ding F, Wu HM: Psychological intervention on psychological state and quality of life of perioperative patients with cervical cancer. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 2011, 26: 2397-2399. (in China)

Li F, Yang JJ, Wang HN, Tan QR, Zhang HW, Wang WZ: Influential factors and non-pharmacal intervention strategies for anxious and depressive state of patients with gastrointestinal tumors in perioperative period. J Fourth Military Medical University. 2009, 30: 264-267. (in China)

Yang LJ: Influence of systematic nursing intervention on living quality of gynecological cancer patients during chemotherapy. Chin Nurs Res. 2008, 22: 1883-1884. (in China)

Mao XH, Li YH, Li YT, Zhu QF, Dai YG, Dong HX: Psychological adjustment and stress of nursing intervention mode on malignant tumor patients psychological status and influence of long-term prognosis. Liaoning J Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2013, 40: 1002-1003. (in China)

Guan JY, Li Y, Luo QY: Effect of psychological Intervention on the bladder irrigation chemotherapy after the operation of bladder cancer. China Clinical Practical Medicine. 2010, 4: 237-238. (in China)

Zhai HP, Cheng Z, Zhu ZL: Effect of psychological intervention on mental health status and quality of life of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Occupation and Health. 2013, 29: 2035-2037. (in China)

Yang QJ, Wang XQ: Study on the impact of psychological intervention on life quality of malignant tumor patients treated with chemotherapy. China J Chinese Medicine. 2012, 27: 396-397. (in China)

Zhao LB, Zhang Y, Li L, Li WW, Zhou WG, Wang Q: Effects of psychological intervention on anxiety, depression and quality of life in cancer patients. J Neuroscience and Mental Health. 2012, 12: 488-490. (in China)

Han L, Lu HH, Li CH, Zheng GW, Zhao LB, Zhang ZG, Song CQ, Lu GL: Effects of psychological intervention on anxiety, depression and pain in cancer patients. J Neuroscience and Mental Health. 2012, 12: 506-508. (in China)

Huang J, Zhao C, Chen XY: Effects of psychological intervention on negative emotion and quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Shandong Medical J. 2010, 50: 50-51. (in China)

Liu YH, Yang XH, Ren XY, Bin J, Xiong Y, Liu WZ: Effects of psychological intervention on anxiety, depression and quality of life in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Shanxi Medical J. 2010, 39: 415-417. (in China)

Xu YH: Effects of psychological intervention on gynecological cancer patients before and after operation. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 2007, 22: 4393-4394. (in China)

Li XM: Treatment function of psychology intervenes to the malignant tumor of the gynecology. Chinese J Practical Medicine. 2009, 36: 8-9. (in China)

Wang SX: The influence of psychological intervention on anxiety, depression and the quality of lives of patients with ovarian cancer. International J Nursing. 2010, 29: 52-54. (in China)

Li D, Zhang HJ, Guo LH: Influence of psychological intervention on depression and anxiety emotions and quality of life of postoperative ovarian cancer patients. Chin Nurs Res. 2010, 24: 1460-1461. (in China)

Shi LX, Gong XY, Yang JY: Effects of psychological intervention on negative emotion of ovarian tumor patients with surgery. Int J Nursing. 2012, 31: 1680-1682. (in China)

Wang F: Effect of psychotherapy on depression and gastrointestinal reactions in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Xinjiang Medical J. 2004, 34: 126-127. (in China)

Zhang CY, Yu RY: Effect of psychological intervention on negative psychological of breast cancer chemotherapy patients. China J Health Psychology. 2011, 19: 1322-1323. (in China)

Meng RF, Liu RH, Wang SJ, Wang MY, Fu JM, Liu JL, Ding YX: Study on the effect of psychological intervention in three step ladder pain relief for patients with later cancer. Nursing Practice and Research. 2011, 8: 129-130. (in China)

Zhang JM: Effect of psychological intervention on quality of life of cancer patients in advanced stage. Nursing Practice and Res. 2013, 10: 131-132. (in China)

Zhang H: Clinical study on the effect of psychological intervention on psychological state of patients with later cancer. Guide of China Medicine. 2012, 10: 116-(in China)

Liu YH, Yang XH, Ren XY, Xiong Y, Bin J: Influence of psychological intervention on negative emotion and immune function of patients with digestive tract tumor. J Clinical Res. 2012, 29: 825-827. (in China)

Li SY, Huang MH, You QY: Influence of psychological intervention on depression and anxiety of patients with digestive system malignancy during first chemotherapy. Fujian Medical J. 2008, 30: 145-146. (in China)

Zhou L: Influence of psychological intervention on quality of life among patients with hematologic tumors. J Qilu Nursing. 2008, 14: 40-41. (in China)

Lou SH, Li L, Ma DP, Fa WL: Effect of psychotherapy on depression and gastrointestinal reactions in tumor patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Nursing Science. 2003, 18: 748-749. (in China)

Huang Y: Effect of psychotherapy on immunologic function in tumor patients after chemotherapy. Modern J Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Med. 2011, 20: 4553-4554. (in China)

Xing NL: Effects of mental intervention on peri-operative anxiety-depression state of patients with carcinoma cervicis. J Clinical Psychosomatic Dis. 2007, 13: 435-436. (in China)

Geng Y, Zhao YN, Li KZ, Wu DD, Liu XF, Liu Y, Yan XH, Zhou HP, Wang H: Clinical observation of mental intervention for anxiety-depression in patients with cancer. J Modern Oncology. 2010, 18: 1412-1414. (in China)

Zhan XH, Cheng XM: Influence of psychological intervention techniques on quality of life of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Chin Nurs Res. 2010, 24: 2127-2128. (in China)

Ji FP: Effect of nursing psychological intervention on the malignant tumor patients’ negative emotions. J Shandong Medical College. 2008, 30: 318-320. (in China)

Cheng K, Wang J, Jia YJ: Clinical observation on effect of mental intervention on increasing quality of life in patients with malignant tumor. Tianjin J Traditional Chinese Med. 2006, 23: 462-464. (in China)

Shi YF, Ren XY, Jiang YJ: Application of psychological intervention in pain relief of cancer patients. Cancer Res and Clinic. 2010, 22: 570-572. (in China)

Zheng YB, Zhuang TY, Wang JY: Study on psychological intervention in cancer patients with postoperative psychonosema. J Modern Oncology. 2007, 15: 86-87. (in China)

Deng LL, Lv HF, Yang N: Effect of psychotherapy on psychological state in cancer patients after chemotherapy. Chinese J Rehabilitation Medicine. 2007, 22: 168-169. (in China)

Li XQ: Effect of psychological nursing on psychological state in cancer patients during chemotherapy. Chinese J Practical Nursing. 2010, 26: 44-45. (in China)

Liu JH: Effect of psychological nursing on quality of life among malignant tumor patient with anxiety. Medical Information. 2013, 26: 370-(in China)

Mao XL, Zhang CH, Lin Y: Effects of mental nursing on the depression and anxiety of the malignancy patient. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. 2008, 8: 2598-2600. (in China)

Zhang YQ: Effect of psychological nursing on psychological state of gynecologic malignancy patients before and after operation. China Practical Medical. 2013, 8: 236-237. (in China)

Xu XC: Influence of psychological care on anxiety and depression feelings of postoperative patients with digestive system malignant tumor. Chin Nurs Res. 2004, 18: 243-244. (in China)

Zheng L, Gao W, Yang M: Effect of psychological nursing care on anxiety and depression of patients with tumor during radiotherapy. J Qilu Nursing. 2008, 14: 1-2. (in China)

Ci YK, Tao FY, Hou J: Effect of psychological nursing intervention on psychological state of cancer patients before chemotherapy. World Health Digest. 2013, 10: 86-87. (in China)

Xia Y: The effect of mental nursing on mental status of cancer patients before interventional therapy. Modern Clinical Nursing. 2009, 8: 50-52. (in China)

Liu SQ: Effect of psychological nursing on psychological status of cancer patients before interventional therapy. World Latest Med Information. 2013, 13: 462-463. (in China)

Guan J, Jie XX: Clinical observation of psychological nursing intervention improving mental status of hospitalized malignant tumor patients. Chinese Community Doctors. 2011, 13: 282-283. (in China)

Gu XL: Application of psychological nursing improving cancer patients’ quality of life. Health Must-Read Magazine. 2012, 11: 352-(in China)

Jin JY, Zhu YA: Effects of psychological and behavior intervention on patients with non-small cell lung cancer during chemotherapy. J Practical Med. 2008, 24: 1341-1342. (in China)

Guan HM, Sun J, Li GM: Effect of psychotherapy on quality of life and emotion of cancer patients. J Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Res. 2002, 6: 3088-(in China)

Wang Y, Xiao WM: Effects of psychological intervention on anxiety and depression in cancer patients. J Taishan Medical College. 2012, 33: 117-118. (in China)

Zheng W, Gao ZH, Tian X: Effects of catharsis therapy and cognitive therapy on psychological status in elderly patients with medium or advanced cancer. Chin J Gerontol. 2008, 28: 1108-1110. (in China)

Tang XY, Mao SY, Luo F, Zhou YQ: Effects of selective psychological intervention on cytokine and unhealthy emotion in patients with breast cancer. J Chongqing Medical University. 2010, 35: 730-733. (in China)

Jia YY: The intervention of stabilization technology on the psychological stress of patients with esophageal carcinoma during the stage of operation. Master’s Thesis. 2012, The general hospital of Chinese People's Liberation Army, Internal Medicine Department, (in China)

Kang R: Effects of mental intervention on relieving pain among patients with breast cancer of the advanced stage. Master’s Thesis. 2007, Shanxi Medical University, Social Medicine Department, (in China)

Li WF: A study on the effect of individual health education on improving the sleeping and anxiety and depression of tumor patients with treatment of microwave ablation survey. Master’s Thesis. 2012, Shandong University, Nursing Department, (in China)

Li YH: Influence of psychological intervention on depression and handling of patients after Miles operation for rectal cancer. Master’s Thesis. 2011, University of South China, Oncology Department, (in China)

Liu L: Study of psychological intervention on emotional disorder and correlative immune indices in patients with cervical cancer in perioperative stage. Master’s Thesis. 2011, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Nursing Department, (in China)

Liu XT: Psycho-behavior intervention on emotional disorder and the changes of T lymphocyte subsets in patients with ovarian cancer. Master’s Thesis. 2008, ChongQing Medical University, Nursing Department, (in China)

Qiu ZY: Effect of mental interventions to lung-cancer-patients’ psychosomatic status and immune function who undergo chemotherapy. Master’s Thesis. 2009, Jilin University, Clinical Medicine Department, (in China)

Sun HT: The influence of psychotherapy on the quality of life and the emotion in radio-therapeutic cancer patients. Master’s Thesis. 2009, Xinjiang Medical University, Psychiatry and Mental Health Department, (in China)

Wei SQ: Breast cancer patients and TH11TH2 emotional and relationship psychological intervention experimental research. Master’s Thesis. 2012, ShanXi Medical University, Epidemiology and Health Statistics Department, (in China)

Yang L: The effect of group psychotherapy on emotion and quality of life to women who underwent modified radical mastectomy. Master’s Thesis. 2008, China Medical University, Psychiatry and Mental Health Department, (in China)

Yu LY: Effects of the entire psychological intervention on the mental symptoms and quality of life of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma after radiotherapy. Master’s Thesis. 2013, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Integrated Western and Chinese Medicine Major Department, (in China)

Zhang J: The effect of psychological intervention on hope and relative factors in the breast cancer patients. PhD thesis. 2010, Harbin Medical University, Social Medicine and Health Management Departmen, in China,

Zhang PH: Study of depression status in cancer patients and relative psychological intervention. Master’s Thesis. 2009, ShiHeZi University, Nursing Department, (in China)

Zhou LJ: Study of effects of personalized music intervention on depression and anxiety among breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. Master’s Thesis. 2009, Central South University, Nursing Department, (in China)

Zheng XL, Liu JH, Wang LH: Lmplement of psychological intervention for tumor patients with clinical practice guidelines for the psychological care. J Nursing Science. 2011, 26: 67-69. (in China)

Zhang LM, Yang J, Jiang LM, Ma XM, Sun JZ: Psychological study of the semi-structured group counseling on patients with malignant tumor. China Health Care & Nutrition. 2013, 23: 1035-1036. (in China)

Liu AM, Jia T, Liu XM, Han XP: Music relaxing therapy on psychological status of the patients with malignant tumors subject to radiofrequency heat therapy. J Nursing Science. 2006, 21: 60-61. (in China)

Cai GR, Li PW, Jiao LP, Hao YX, Sun GX, Lu L: Clinical observation of music therapy combined with anti-tumor drugs in treating 116 cases of tumor patients. Chinese J Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2001, 21: 891-894. (in China)

Fu YZ, Dai DL, Zhou X, Liang QH: Investigation of music therapy in improving anxiety and depression of breast cancer patients of the advanced stage during FEC chemotherapy. Chinese J Misdiagnostics. 2009, 9: 8312-8313. (in China)

Li MF, Tian DF, Yu LY, Liu G: Effects of an early psychological intervention on anxiety and depression of nasopharyngeal cancer patients after radiotherapy. J Clinical Res. 2012, 29: 1164-1165. (in China)

Yuan ML, Wu JJ: Effects of early psychological interventions for patients with advanced cancer on psychological status and quality of life. Guangzhou Medical J. 2013, 44: 27-29. (in China)

Wu L, Wang SJ: Psychotherapy improving depression and anxiety of patients treated with chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy. J Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Res. 2003, 7: 2462-2463. (in China)

Li L, Wang WL, Zhou LH, Huang XH: Effect of therapeutic communication on postoperative anxiety and depression in patients with gynecological cancer. Anhui Medical and Pharmaceutical J. 2011, 15: 1621-1623. (in China)

Zheng JH, Zheng CL, Guo HP: Influence of therapeutic communication system on depression emotion of postoperative tumor patients undergoing chemotherapy. Chinese J Practical Nursing. 2012, 28: 5-8. (in China)

Han QY, Liu FZ: Effects of psychotherapy on negative emotions of cancer patients. International J Nursing. 2007, 26: 515-517. (in China)

Huang LT, Qin QL, Qiu XY, Shi YF: Effects of comprehensive mental intervention on anxiety and depression of cancer patients. Youjiang Medical J. 2011, 39: 323-324. (in China)

Zhao Y, Zhang JR, Wang SM: Comprehensive psychotherapy for anxiety and distress of patients with cancer. Chin Ment Health J. 2000, 14: 422-423. (in China)

Ren BY, Tang SY, Liu XF, Zhang J, Zhang L, Deng C, Huang XP, Liu HW, Ran WH, Li G: Effect of comprehensive psychotherapy on psychology of cancer patients. China Pharmacy. 2010, 21: 2107-2108. (in China)

Bu XM, Wang X, Cao LJ, Zhu GC: Effect of comprehensive relaxation training on anxiety and depression in patients with hepatic carcinoma. J Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Res. 2005, 9: 16-17. (in China)

Chen DF, Peng YH, Mo XS, You XM, Zhong L, Chen SX, Li LQ: Evaluation the affect of psychological counseling intervention on the immune function in the preoperative anxiety patients with liver cancer. Chinese J Modern Nursing. 2009, 15: 2360-2364. (in China)

Dai YH, Hou AH, Qu SP: Impact of psychological nursing on cancer patients’ anxiety and coping style. J Nursing Science. 2011, 26: 77-78. (in China)

Fan FL, Pan HL: Effect of therapeutic communication in the treatment of anxiety of patients with radiation therapy and chemotherapy after cervical cancer surgery. Chinese Clinical Nursing. 2012, 4: 58-59. (in China)

Fu ZZ, Wang Y, Cheng SH, Bi R, Zhang LJ, Gu T, Cao JL: Anxiety status and nursing care intervention on cancer patients suffering from pain. Chinese J Coal Industry Medicine. 2010, 13: 608-609. (in China)

Han FM: Effect of psychological intervention anxiety of patients with breast cancer. Nursing Practice and Res. 2008, 5: 103-104. (in China)

Jiang JF, Chen LJ, Lao YC, Xu L, Chen MZ, Chen ZB, Cen SF, Liu ZH: Impact of imagery relaxation therapy on relieving chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Guangxi Medical University. 2008, 25: 981-982. (in China)

Jiao GH, Qiu XJ, Xu MH: Effect of psychological counseling on anxiety and coping styles of ovarian cancer patients before the operation. J Guangdong Medical College. 2011, 29: 505-507. (in China)

Li HP, Du H, Zhang RF: Influence of effective communication on anxiety of patients with Miles operation for rectal cancer. Chinese J Misdiagnostics. 2008, 8: 1068-1069. (in China)

Lou SH, Hao YF, Ma DP: Clinical research of effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and gastrointestinal reactions in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Chinese J Rehabilitation Medicine. 2005, 20: 604-605. (in China)

Ni BQ, Chen RX, Zheng LC, Wu MJ, Wu JW: Effect of psychotherapy on the quality of life of cancer patients undergoing thermo-chemotherapy. J Modern Oncology. 2007, 15: 857-860. (in China)

Pang XY, Wang X: Clinical assessment of psychological intervention in patients with breast cancer before and after operation. Shanxi Medical J. 2007, 36: 935-936. (in China)

Su X, Wang WL: Effect of therapeutic communication on preoperative anxiety in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Chinese J Nursing. 2010, 45: 869-872. (in China)

Tian LH, Guan J, Wang JL, Long L, Hu KQ, He KL, Liu H, Zhan HM: Clinical outcome of cluster change nursing intervention in nursing anxiety for the therioma patients. Nursing Practice and Res. 2013, 10: 4-5. (in China)

Wang RM, Lu HC, Chen M: Effects of psychological intervention anxiety and postoperative recovery of patients with colorectal cancer during perioperative period. Chinese J Misdiagnostics. 2008, 8: 5575-5576. (in China)

Wu JQ, Zhang XL: Effect of nursing intervention on anxiety of patients with gastric carcinoma. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China. 2010, 8: 126-(in China)

You TH, Wang R, Yan XY: Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on anxiety of breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. J Practical Medicine. 2010, 26: 689-690. (in China)

Yu YR: Effect of psychological intervention on anxiety of breast cancer patients. China Health Care & Nutrition. 2013, 8: 65-(in China)

Cao YF: Nursing research of music relaxation intervention after radical mastectomy. J Qiqihar University of Medicine. 2011, 32: 3189-3190. (in China)

Zhao X, Zhang LM: The effects of therapeutic communication system on preoperative anxiety in patients with gynecologic cancer. Mod Hosp. 2011, 11: 87-89. (in China)

Zheng HH, Fan AX, Long L, Liu LH, Fan XH: Influence of preoperative psychological intervention on preoperative anxiety of patients with malignant tumor. Anti-Tumor Pharmacy. 2012, 2: 235-237. (in China)

Zhou GX: Effects of psychological, cognitive and behavioral intervention on surgical patients with breast cancer. Today Nurse. 2010, 4: 68-69. (in China)

Cao SQ, Jiang YH: Evaluation of the effect of psychological intervention in lung cancer patients. J Clinical Psychosomatic Dis. 2011, 17: 367-368. (in China)

Mu YJ, Xie Y, Xue L, Chai YJ, Zhang YJ, Hao XY: Effect of nursing intervention on anxiety before transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Med Res and Educ. 2012, 29: 48-51. (in China)

Guo Z, Tang H, Li H, Tan SK, Feng KH, Huang YC, Bu Q, Jiang W: The benefits of psychosocial interventions for cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013, 11: 121-10.1186/1477-7525-11-121.

Zhou KN, Li XM, Yan H, Dang SN, Wang DL: Effects of music therapy on depression and duration of hospital stay of breast cancer patients after radical mastectomy. Chin Med J. 2011, 124: 2321-2327.

Qiu JY, Chen WJ, Gao XF, Xu Y, Tong HQ, Yang M, Xiao ZP, Yang M: A randomized controlled trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy for Chinese breast cancer patients with major depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013, 34: 60-67. 10.3109/0167482X.2013.766791.

Li XM, Zhou KN, Yan H, Wang DL, Zhang YP: Effects of music therapy on anxiety of patients with breast cancer after radical mastectomy: a randomized clinical trial. J Adv Nurs. 2012, 68: 1145-1155. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05824.x.

Yang RT, Huang XW: Meta-analysis of the effects of psychological intervention on physical and mental condition in cancer patients. China Caner. 2009, 18: 187-190. (in China)

Jiang XM, Mi DH, Wang HQ, Zhang L: Mental intervention for cancer patients with depression: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chinese J Evidence-based Medicine. 2010, 10: 352-355. (in China)

Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS: Is it beneficial to involve a family member? a meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004, 23: 599-611.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernet S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen YC, Huang YQ, Zhang MY, Alonso L, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004, 291: 2581-2590.

Yang YL, Liu L, Wang XX, Wang Y, Wang L: Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014, 9: e94804-10.1371/journal.pone.0094804.

Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, Sohl S, Cannella D, Targhetta V: Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2010, 33: 1-14. 10.1007/s10865-009-9227-2.

Wetherell JL, Unützer J: Adherence to treatment for geriatric depression and anxiety. CNS Spectr. 2003, 8: 48-59.

Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Zhao P, Li GL, Wu LY, He J: Report of incidence and mortality in China cancer registries, 2009. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013, 25: 10-21.

Lebel S, Devins GM: Stigma in cancer patients whose behavior may have contributed to their disease. Future Oncol. 2008, 4: 717-733. 10.2217/14796694.4.5.717.

Carlsen K, Jensen AB, Jacobsen E, Krasnik M, Johansen C: Psychosocial aspects of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005, 47: 293-300. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.08.002.

Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S: The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001, 10: 19-28. 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::AID-PON501>3.0.CO;2-6.