Abstract

Background

Differences in cancer awareness between individuals may explain variations in healthcare seeking behaviour and ultimately also variations in cancer survival. It is therefore important to examine cancer awareness and to investigate possible differences in cancer awareness among specific population subgroups. The aim of this study is to assess awareness of cancer symptoms, risk factors and perceived 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancer in a Danish population sample and to analyse the association between these factors and socio-economic position indicators.

Methods

A population-based telephone survey was carried out among 1,000 respondents aged 30–49 years and 2,000 respondents aged 50 years and older using the Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer measure. Information on socio-economic position was obtained by data linkage through Statistics Denmark. Prevalence ratios were used to determine the association between socio-economic position and cancer awareness.

Results

A strong socio-economic gradient in cancer awareness was found. People with a low educational level and a low household income were more likely to have a lower awareness of cancer symptoms, cancer risk factors and the growing risk of cancer with age. Furthermore, men and people outside the labour force tended to be less aware of these factors than women and people within the labour force. However, women were more likely than men to lack awareness of the relationship between age and cancer risk. No clear associations were found between socio-economic position and lack of awareness of 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancers.

Conclusions

As cancer awareness has shown to be positively associated with cancer-related behaviour, e.g. healthcare seeking, consideration must be given to tackle inequalities in cancer awareness and to address this issue in future public health strategies, which should be targeted at and tailored to the intended recipient groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Large variations in cancer survival exist between countries across a range of cancer types. Survival rates are generally lower in Denmark than in comparable countries [1, 2]. Even within countries, survival rates vary much between patient groups with the same type of cancer, and for most cancers people with lower socio-economic position (SEP) have poorer outcomes than their socioeconomically more affluent counterparts [3, 4].

These variations between and within countries are undoubtedly multifactorial and complex, but a growing body of research suggests that differences in stage progression at the time of treatment initiation may explain some of this variation; thus, differences in the time that passes from the first symptom is experienced until diagnosis and treatment seem to play a crucial role [5, 6]. Recent years have seen a stronger focus on cancer awareness and its possible effect on the ‘patient interval’ (i.e. the time from the first symptom is experienced until healthcare is sought [7]) [8]. Across a range of different cancer types, both quantitative and qualitative studies have found an association between low awareness of cancer symptoms and risk factors, and a long patient interval [9, 10]. Studies have also indicated that the patient interval accounts for a substantial part of the time to diagnosis and treatment [11, 12]. Cancer awareness accordingly seems to be a potentially modifiable contributor to the variations seen in healthcare seeking and, ultimately, survival [8]. It is therefore important to assess cancer awareness among the general population and to investigate possible associations with different subgroups.

Few studies have explored cancer awareness in the general population, and they find that being a man, living alone, belonging to an ethnic minority group and having a low level of education are independently associated with a lower level of cancer awareness [13–15]. In these studies, all SEP indicators are based on self-reporting. Owing to the existence of a Civil Registration System (CRS) in Denmark with complete, updated information on all Danish citizens [16], a range of highly valid and complete SEP indicators can be linked to survey data at the individual level in this study.

The aim of the present study is to assess awareness of cancer symptoms, risk factors and perceived 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancer in a Danish population sample and to analyse the association between these factors and several register-based SEP indicators.

Methods

Study population and data collection

Data on cancer awareness among the general population in Denmark were collected as part of the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP), Module 2 [17]. The survey consisted of a 20-minute computer-assisted telephone interview undertaken by trained native-language interviewers from the market research company Ipsos MORI using the Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer (ABC) measure [18].

In Denmark, a target study population of 1,000 respondents aged 30–49 years and 2,000 respondents aged 50 years and older was initially defined. Using the Danish CRS [16], a random study base was selected consisting of 20,000 persons aged 30–49 years and 40,000 persons aged 50 years and older. Among these 60,000 persons, a total of 6,570 persons (11.0%) were excluded because of research protection (i.e. publicly recorded rejection to be contacted for research purposes). For the remaining 53,430 persons, full name and complete address were obtained from the CRS and used by the Danish market research and consulting firm NN Markedsdata to obtain the phone number (landline and/or mobile) belonging to the identified person. Phone numbers could not be obtained for 6,309 (11.8%) persons, who were therefore excluded. Lastly, another 55 (0.1%) persons were excluded just before the data collection began, either because of a newly established research protection status, emigration from Denmark, or because the person had passed away. In total, 47,066 persons (78.4% of the study base) were thus eligible for being contacted to answer the ABC measure (Figure 1).

The Danish survey was conducted from 31 May to 4 July 2011, and each person was contacted on up to seven occasions at different weekdays and times. Interviews were not performed if the person was unable to speak or understand Danish.

Survey measure

The ABC measure was applied; the development and the validation of the ABC measure is described elsewhere [18]. It explores awareness of cancer symptoms by using recognition as well as recall [19]; awareness of risk factors for cancer; awareness of growing risk of cancer with age; awareness of perceived 5-year survival from cancer; access to a doctor; anticipated healthcare seeking for cancer symptoms; anticipated barriers to healthcare seeking; beliefs about cancer in general; beliefs about cancer screening and actual screening behaviour. In addition, the measure explores smoking status, self-rated health and personal experience of cancer (own or close relatives, if any). The English version of the ABC measure was translated into Danish in accordance with the WHO guidelines for translation procedures, which included forward and backward translations [20].

Dependent variables

Data reported here include awareness of cancer symptoms using the recognition method, awareness of risk factors for cancer, awareness of growing risk of cancer with age and awareness of 5-year survival from four different types of cancer.

Awareness of cancer symptoms

This awareness was measured by asking respondents whether they thought that a specific symptom could be a warning sign of cancer. In total, 11 different possible warning signs were stated in a rotated order with yes/no response options. These warning signs were unexplained lump or swelling; persistent, unexplained pain; unexplained bleeding; persistent cough or hoarseness; change in bowel or bladder habits; persistent difficulty in swallowing; change in the appearance of a mole; sore that does not heal; unexplained night sweats; unexplained weight loss; and unexplained tiredness. Don’t know was not indicated as a response category, but such a response was noted by the interviewer. A score of 1 point was given for a correct answer (yes), while an incorrect answer (no) was given 0 points. Don’t know was classified as an incorrect answer. The total score of cancer symptom awareness was computed (possible range: 0–11) and dichotomised into low and high awareness using the median split.

Awareness of risk factors for cancer

In a rotated order, respondents were asked whether they thought that a specific factor could increase their risk of getting cancer. Respondents could answer strongly disagree, tend to disagree, tend to agree, or strongly agree for 13 different risk factors: Smoking; exposure to passive smoking; drinking more than 1 unit of alcohol a day; eating less than 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day; eating red or processed meat once a day or more; being obese; getting sunburnt more than once as a child; being over 70 years old; having a close relative with cancer; infection with human papillomavirus (HPV); not doing much physical activity; using a solarium; and exposure to ionising radiation from, for example, radioactive materials, x-rays, or radon. The answers tend to agree and strongly agree were given 1 point; and strongly disagree, tend to disagree and don’t know were given 0 points (possible range: 0–13). On the basis of the median split, awareness of risk factors for cancer was categorised into low and high awareness.

Awareness of growing risk of cancer with age

This element was assessed by asking the respondents the following question: “Over the next year, which of these groups of people, if any, do you think is most likely to be diagnosed with cancer?”. Four possible response categories were given: 30-year-olds, 50-year-olds, 70-year-olds, or people of any age are equally likely to be diagnosed with cancer. Again, a response of don’t know was accepted, but was not mentioned by the interviewer. The answer 70-year-olds was coded as correct, while all other answers were coded as incorrect.

Awareness of 5-year survival from four different types of cancer

Respondents were asked to estimate the 5-year survival rate from four different types of cancer: “Out of 10 people diagnosed with bowel/breast/ovarian/lung cancer, how many do you think would be alive five years later?” The interviewers recorded the stated number of people (0–10), and the following answers were coded as correct: Bowel (4–5), breast (8–9), ovarian (3–4) and lung (1–2) [21, 22]. To analyse the possible association between SEP and awareness of survival from the four different types of cancer, the data were dichotomised into correct estimation and underestimation/overestimation.

Independent variables

Information on SEP indicators was obtained by data linkage to Statistics Denmark [23]. For each person in the study population, we obtained information on seven SEP indicators: gender (female, male); age (30–49, 50–69 and 70+ years); marital status (married/cohabiting, living alone); ethnicity (ethnic Dane, immigrant/descendant); level of education (low: ≤10 years, middle: >10 ≤ 15 years and high: >15 years) according to UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) groups [24]; occupation (in the labour force: employed and students, outside the labour force: unemployed, early retirement pensioner, disability retirement pensioner, personal or sick leave and retired: voluntarily retired person (special or old-age pensioner); and, lastly, OECD-modified disposable household income adjusted for number of adults and children in the household [25]. To level out yearly variation, this SEP indicator was calculated as an average for the preceding three years and categorised as low, middle and high income (low: ≤16,536 £/year, middle: >16,536 ≤ 33,095 £/year and high: >33,095 £/year) based on the 20%, 60% and 20% income distribution among the 60,000 persons in the study base. To examine the association between previous personal experiences with cancer and cancer awareness, we retrieved data from the Danish Cancer Registry on all registered cancer diagnoses (yes/no) for each person within the past 10 years [26]. For these register-based SEP indicators, missing data ranged from 0% for age, gender and information on cancer diagnosis to 3.9% for information about educational level for the study base of 60,000 persons. Data on close relatives with cancer (yes/no) and self-rated health (very good, good, fair, poor and very poor dichotomised into good and fair/poor) were obtained from the ABC survey.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using Stata version 13.1. Statistical analyses were performed with unweighted data, because weighting may introduce additional bias. Prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were used to determine the association between SEP indicators and awareness of cancer symptoms, risk factors for cancer, growing risk of cancer with age and 5-year survival for four different types of cancer. Unadjusted analyses were carried out with each of the independent variables, and an adjusted model was used to control for possible confounding. PRs were chosen over odds ratios (ORs) as ORs may overestimate the associations when there is a high prevalence of the dependent variables [27].

Ethics and approval

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. no. 2011-41-6237) and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority. In accordance with the Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics, the study needed no further approval (Report no. 128/2010).

Results

Response

To obtain inclusion of 1,000 respondents aged 30–49 years and 2,000 respondents aged 50 years or older, we approached a random sample of 11,297 persons. A response rate of 36.7% was achieved (Table 1); this was estimated as the number of completed interviews divided by the number of eligible persons made contact to. The SEP of the respondents and of the study base are shown in Table 2. A higher proportion of the respondents than of the entire study base of 60,000 persons were females, younger, married/cohabiting, ethnic Danes, had a high-level education, a high household income and were in the labour force. The differences were statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

Awareness of cancer symptoms

The two most well-known symptoms of cancer were a change in the appearance of a mole and an unexplained lump or swelling. These two symptoms were recognised by 97.2% and 94.3% of the respondents, respectively. The lowest awareness of cancer symptoms was found for unexplained night sweats (15.6%) and a sore that does not heal (67.8%).

The median number of cancer symptoms recognised by the respondents was nine out of 11. The associations between SEP and recognition of less than nine symptoms of cancer are presented in Table 3. In both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, several of the SEP indicators were statistically significantly associated with awareness of cancer symptoms. Especially men, immigrant/descendants, people with low-level education, people outside the labour force, people with a low household income and people with no close relatives with cancer were more likely to recognise less than nine symptoms of cancer than women, ethnic Danes, people with a high-level education, people in the labour force, people with a high household income and people with close relatives with cancer, respectively.

Sensitivity analyses revealed similar social gradients in awareness of cancer symptoms based on recognition of both less than five and less than seven symptoms, but the PRs were generally higher in these analyses. For example, the PR of recognising less than five symptoms was 3.81 (95% CI 2.23-6.53) (adjusted model; data not shown) when people with a low-level education were compared with people with a high-level education. The corresponding PR was 1.57 (95% CI: 1.39-1.78) when the cut-off used was fewer than nine symptoms.

Awareness of risk factors for cancer

The highest awareness of risk factors for cancer was found for smoking (96.5%) and using a sunbed (95.5%), while the lowest awareness was found for infection with HPV (23.6%) and intake of less than five daily portions of fruit and vegetables (41.0%).

The median number of risk factors recognised by respondents was nine out of 13. Certain characteristics were strongly associated with recognising less than nine risk factors for cancer; these include being a man, older, having a low-level education, or having a low household income (Table 4). Again, sensitivity analyses showed a stronger social gradient (data not shown).

Awareness of growing risk of cancer with age

In total, 24% of the respondents were aware that 70-year-olds are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than 30-year-olds, 50-year-olds and people of any age. However, the majority (42%) responded that people of any age are equally likely to be diagnosed with cancer or that 50-year-olds are more likely (30%). Being a woman, having a low level of education, and a low income were associated with non-recognition of growing risk of cancer with age (Table 5).

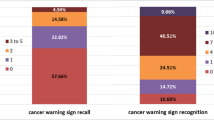

Awareness of 5-year survival from four different types of cancer

The 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancer was correctly identified by 42%, 49%, 9% and 19% of the respondents, respectively. For ovarian and lung cancer, a large majority (86 and 78%, respectively) of the respondents overestimated the 5-year survival, whereas almost half of the respondents underestimated survival from breast cancer. The distributions of the respondents’ estimations (underestimating, correctly estimating and overestimating) are shown in Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents underestimating, correctly estimating and overestimating the 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancer*. *Missing data for awareness of 5-year survival: bowel cancer: n = 154, breast cancer: n = 88, ovarian cancer: n = 194, lung cancer: n = 98, including response categories don’t know and did not answer.

Table 6 shows the associations between the SEP indicators and underestimation/overestimation of the 5-year cancer survival. People outside the labour force were more likely than people within the labour force to wrongly estimate the 5-year survival from breast cancer, and men were more likely to wrongly estimate the 5-year survival from lung and ovarian cancer than women. Furthermore, people with a low and middle income and people with no close relatives with cancer were less aware of the 5-year survival from bowel cancer than people with a high income and with close relatives with cancer.

Discussion

A strong socio-economic gradient was found in cancer awareness; thus, people with a low educational level and a low household income were more likely to have a lower awareness of possible cancer symptoms, factors that can influence the risk of getting cancer, and the growing risk of cancer with age than people with a high-level education and people with a high household income. The sensitivity analyses showed that the associations between SEP and the respondents’ awareness of symptoms and risk factors were independent of the median cut-off; thus, the findings appear to be robust. We also saw a trend that men and people outside the labour force were less aware of these factors than were women and people in the labour force, respectively. However, women were more likely than men to lack awareness of the relation between age and cancer. No clear associations were found between SEP and lack of awareness of the 5-year survival from bowel, breast, ovarian, and lung cancer.

Our study supports findings from previous studies that people with a low SEP are generally more likely to be less aware of cancer than people with a high SEP [13, 15, 28, 29]. The findings also mirror the findings that cancer survival has a social gradient [3]. However, the mechanisms underlying the association between SEP and cancer awareness are not well understood. It has been suggested that, to some degree, the association may be related to health illiteracy and thus a lower capacity among people with lower SEP to obtain, process and understand health information [30].

It has also been rightly questioned whether a heightened awareness in itself may lead to the desired change in behaviour [31, 32]; knowledgeable people do not always make wise decisions [14, 33]. Recent research has also emphasised the role of other factors in the link between cancer awareness and cancer-related behaviour. Among others, it has been suggested that anticipated barriers to healthcare seeking and beliefs about cancer may mediate this link [33–35]. Although the role of cancer awareness as a determinant of behaviour should not be overemphasised, cancer awareness will often be an important step towards healthcare seeking and screening attendance [19, 36, 37].

The present study found that the two most commonly recognised symptoms of cancer were a change in the appearance of a mole and an unexplained lump or swelling and that smoking and sunbed use were the most well-known risk factors. On the other hand, unexplained night sweats and infection with HPV were the least recognised symptom and risk factor, respectively. These findings may reflect that Danish national campaigns have focused strongly on breast and skin cancers [38–40]. Thus, campaigns addressing cancer symptoms and risk factors may help the population evaluate these more accurately. Accurate evaluation of cancer symptoms and risk factors may reduce the patient interval [41, 42], increase screening uptake [43, 44] and encourage cancer risk-reducing actions [45, 46]. Our findings may also reflect the fact that a lump is a specific symptom, while unexplained night sweats, for example, are a less specific symptom that may be more readily associated with conditions such as menopause and infections than with cancer [47], and may therefore not immediately be considered a symptom of cancer. Likewise, in a comprehensive review by Macleod et al.[10], vague, ambiguous and more common symptoms were associated with a longer patient interval.

Cancer is primarily a disease of the elderly, and for most cancers the incidence rate increases with age [48]. However, the majority of the respondents tended to think that people of any age were equally likely to be diagnosed with cancer. This was a surprising finding; but as implied by others [37, 43], individuals may not conceptualise non-modifiable factors (such as age and gender) as risk factors, whereas modifiable factors (such as smoking and alcohol use) may be more easily seen as part of the conceptual framework for cancer risk among laypeople. Nevertheless, awareness about both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors is important because awareness may facilitate healthcare seeking [28, 49].

Awareness of the 5-year survival from bowel and breast cancer was fairly high; however, only a small percentage of the respondents correctly identified the 5-year survival from ovarian and lung cancer. This may be due to inadequate communication about the chances of survival from these cancer types. However, the results for lung cancer may also be partly explained by end-aversion bias, i.e. the tendency to avoid the extremes of a scale.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of the present study was the use of the Danish CRS. All Danish residents are registered in the CRS which contains complete information on any Danish resident’s date of birth, gender, migration, etc. Owing to our use of the CRS, we were able to define a study base of 60,000 persons, a representative sample of the entire Danish population aged 30 years and older. Furthermore, the use of the CRS and the data linkage to a range of register-based SEP indicators provided us with precise and valid insight into variables that may be related to cancer awareness. Naturally, the SEP indicators capture correlated aspects. Still, since the correlation is not a hundred percent, each indicator contributes with unique information about the association with cancer awareness.

To analyse associations between SEP and cancer awareness of symptoms and risk factors, cancer awareness was categorised into low/high using the median split procedure. One of the shortcomings of this procedure is that the median is contingent upon the particular sample on which it is based [50, 51]. Thus, respondents categorised as having a low cancer awareness in this sample may be categorised as having a high cancer awareness in another sample. However, sensitivity analyses using both awareness of less than five and less than seven cancer symptoms and risk factors showed a similar, but intensified social gradient in cancer awareness.

A limitation of the study was the modest response rate. Only 36.7% of the persons whom we made contact to agreed to participate in the study. Unfortunately, response rates have been declining over the past decades and telephone surveys have been particularly affected by this decline [52]. However, by collecting data using a telephone interview, the respondent did not have the possibility to look for information elsewhere. This advantage could not have been achieved with paper-based or web-based surveys. The respondents completing the ABC measure were more often females, younger, married/cohabiting, had a high-level education and a high household income than people in the study base. As a consequence, selection bias may in some way affect the generalisability of the findings since women and persons with a high-level education and a high household income were generally more aware of cancer symptoms and risk factors than men and persons with a low educational level and a low household income. Consequently, the actual awareness level in the population is most probably lower than estimated here.

Conclusion and implications

The results of this study indicate that people with a low educational level and a low household income are less aware of cancer than people with a high-level education and a high household income, respectively. Awareness about possible cancer symptoms, risk factors for developing cancer and survivability has shown to be positively associated with cancer-related behaviour, such as healthcare seeking and screening uptake. Thus, consideration must be given to tackle the current inequality in cancer awareness and to address this issue in future public health strategies. It is important that these strategies are targeted and tailored to the intended recipient groups. Otherwise, strategies may unintentionally increase social inequality in cancer awareness, as individuals with higher SEP often acquire and adapt to new health information at a faster rate than individuals with lower SEP [53].

In conclusion, decisions on healthcare seeking for potential cancer symptoms is a complicated process that is shaped by much more than simply awareness. Thus, the present study should be seen as part of a larger framework of research examining possible associations between SEP indicators and other factors that may influence cancer-related behaviour, such as beliefs about cancer and psychological and practical barriers to healthcare seeking.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRS:

-

Civil registration system

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- ICBP:

-

International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PR:

-

Prevalence ratio

- SEP:

-

Socio-economic position.

References

Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, Nur U, Tracey E, Coory M, Hatcher J, McGahan CE, Turner D, Marrett L, Gjerstorff ML, Johannesen TB, Adolfsson J, Lambe M, Lawrence G, Meechan D, Morris EJ, Middleton R, Steward J, Richards MA, ICBP Module 1 Working Group: Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9760): 127-138.

Storm HH, Kejs AM, Engholm G, Tryggvadottir L, Klint A, Bray F, Hakulinen T: Trends in the overall survival of cancer patients diagnosed 1964–2003 in the Nordic countries followed up to the end of 2006: the importance of case-mix. Acta Oncol. 2010, 49 (5): 713-724.

Dalton SO, Schuz J, Engholm G, Johansen C, Kjaer SK, Steding-Jessen M, Storm HH, Olsen JH: Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003: Summary of findings. Eur J Cancer. 2008, 44 (14): 2074-2085.

Coleman MP, Rachet B, Woods LM, Mitry E, Riga M, Cooper N, Quinn MJ, Brenner H, Esteve J: Trends and socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England and Wales up to 2001. Br J Cancer. 2004, 90 (7): 1367-1373.

Ibfelt E, Kjaer SK, Johansen C, Hogdall C, Steding-Jessen M, Frederiksen K, Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Dalton SO: Socioeconomic position and stage of cervical cancer in Danish women diagnosed 2005 to 2009. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21 (5): 835-842.

Walters S, Maringe C, Butler J, Brierley JD, Rachet B, Coleman MP: Comparability of stage data in cancer registries in six countries: lessons from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership. Int J Cancer. 2013, 132 (3): 676-685.

Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, Walter FM, Emery J, Scott S, Campbell C, Andersen RS, Hamilton W, Olesen F, Rose P, Nafees S, van Rijswijk E, Hiom S, Muth C, Beyer M, Neal RD: The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2012, 106 (7): 1262-1267.

Richards MA: The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative in England: assembling the evidence. Br J Cancer. 2009, 101 (Suppl 2): S1-S4.

Smith LK, Pope C, Botha JL: Patients’ help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: a qualitative synthesis. Lancet. 2005, 366 (9488): 825-831.

Macleod U, Mitchell ED, Burgess C, Macdonald S, Ramirez AJ: Risk factors for delayed presentation and referral of symptomatic cancer: evidence for common cancers. Br J Cancer. 2009, 101 (Suppl 2): S92-S101.

Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Laurberg S: Delay of diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer–a population-based Danish study. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008, 32 (1): 45-51.

Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Sondergaard J, Olesen F: Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer: a cohort study of 2,212 newly diagnosed cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011, 11: 284-

Brunswick N, Wardle J, Jarvis MJ: Public awareness of warning signs for cancer in Britain. Cancer Causes Control. 2001, 12 (1): 33-37.

Weinstein ND: What does it mean to understand a risk? Evaluating risk comprehension. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999, 25 (25): 15-20.

Robb K, Stubbings S, Ramirez A, Macleod U, Austoker J, Waller J, Hiom S, Wardle J: Public awareness of cancer in Britain: a population-based survey of adults. Br J Cancer. 2009, 101 (Suppl 2): S18-S23.

Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO, Mortensen PB: The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006, 53 (4): 441-449.

Butler J, Foot C, Bomb M, Hiom S, Coleman M, Bryant H, Vedsted P, Hanson J, Richards M, ICBP Working Group: The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: an international collaboration to inform cancer policy in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Health Policy. 2013, 112 (1–2): 148-155.

Simon AE, Forbes LJ, Boniface D, Warburton F, Brain KE, Dessaix A, Donnelly M, Haynes K, Hvidberg L, Lagerlund M, Petermann L, Tishelman C, Vedsted P, Vigmostad MN, Wardle J, Ramirez AJ, ICBP Module 2 Working Group, ICBP Programme Board and Academic Reference Group: An international measure of awareness and beliefs about cancer: development and testing of the ABC. BMJ Open. 2012, 2 (6): 10-1136/bmjopen-2012-001758. Print 2012

Waller J, McCaffery K, Wardle J: Measuring cancer knowledge: comparing prompted and unprompted recall. Br J Psychol. 2004, 95 (Pt 2): 219-234.

WHO: Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. [http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/print.html]

Kræftens Bekæmpelse: 5-års aldersstandardiseret relativ overlevelse (RS) i procent med 95% sikkerhedsintervaller (CI) for danske kræftpatienter 1995–2009. [http://www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Dataformidling/Sundhedsdata/Kraft/Kraeftoverlevelse.aspx]

Sundhedsstyrelsen: Sygehusbaseret overlevelse efter diagnose for otte kræftsygdomme i perioden 1998–2009. 2011, Sundhedsstyrelsen: København

Statistics Denmark: About us. [http://www.dst.dk/en/OmDS.aspx]

UNESCO Institute for Statistics: ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education. [http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-standard-classification-of-education.aspx]

OECD Project on Income Distribution and Poverty: What are equivalence scales?. [http://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/OECD-Note-EquivalenceScales.pdf]

Storm HH, Michelsen EV, Clemmensen IH, Pihl J: The Danish Cancer Registry–history, content, quality and use. Dan Med Bull. 1997, 44 (5): 535-539.

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN: Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003, 3: 21-

Wardle J, Waller J, Brunswick N, Jarvis MJ: Awareness of risk factors for cancer among British adults. Public Health. 2001, 115 (3): 173-174.

Keeney S, McKenna H, Fleming P, McIlfatrick S: An exploration of public knowledge of warning signs for cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011, 15 (1): 31-37.

von Wagner C, Good A, Whitaker KL, Wardle J: Psychosocial determinants of socioeconomic inequalities in cancer screening participation: a conceptual framework. Epidemiol Rev. 2011, 33 (1): 135-147.

Cook PA, Bellis MA: Knowing the risk: relationships between risk behaviour and health knowledge. Public Health. 2001, 115 (1): 54-61.

Calman KC: Cancer: science and society and the communication of risk. BMJ. 1996, 313 (7060): 799-802.

Sheikh I, Ogden J: The role of knowledge and beliefs in help seeking behaviour for cancer: a quantitative and qualitative approach. Patient Educ Couns. 1998, 35 (1): 35-42.

Lagerlund M, Hedin A, Sparen P, Thurfjell E, Lambe M: Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge as predictors of nonattendance in a Swedish population-based mammography screening program. Prev Med. 2000, 31 (4): 417-428.

Simon AE, Waller J, Robb K, Wardle J: Patient delay in presentation of possible cancer symptoms: the contribution of knowledge and attitudes in a population sample from the United kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19 (9): 2272-2277.

Wilkinson AV, Vasudevan V, Honn SE, Spitz MR, Chamberlain RM: Sociodemographic characteristics, health beliefs, and the accuracy of cancer knowledge. J Cancer Educ. 2009, 24 (1): 58-64.

McCaffery K, Wardle J, Waller J: Knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions in relation to the early detection of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom. Prev Med. 2003, 36 (5): 525-535.

Koster B, Thorgaard C, Philip A, Clemmensen I: Sunbed use and campaign initiatives in the Danish population, 2007–2009: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011, 25 (11): 1351-1355.

Kræftens Bekæmpelse: Støt Brysterne. [http://stoetbrysterne.dk/]

Kræftens Bekæmpelse: Skru ned for solen. [http://www.cancer.dk/forebyg/skru-ned-for-solen/]

Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, Auyeung V, McGurk M: Barriers and triggers to seeking help for potentially malignant oral symptoms: implications for interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2009, 69 (1): 34-40.

Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, Halpern AC, Fine JA, Barnhill RL, Berwick M: Patient knowledge, awareness, and delay in seeking medical attention for malignant melanoma. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999, 52 (11): 1111-1116.

Pearlman DN, Clark MA, Rakowski W, Ehrich B: Screening for breast and cervical cancers: the importance of knowledge and perceived cancer survivability. Women Health. 1999, 28 (4): 93-112.

Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R: Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008, 17 (9): 1477-1498.

Sanderson SC, Waller J, Jarvis MJ, Humphries SE, Wardle J: Awareness of lifestyle risk factors for cancer and heart disease among adults in the UK. Patient Educ Couns. 2009, 74 (2): 221-227.

Waller J, Robb K, Stubbings S, Ramirez A, Macleod U, Austoker J, Hiom S, Wardle J: Awareness of cancer symptoms and anticipated help seeking among ethnic minority groups in England. Br J Cancer. 2009, 101 (Suppl 2): S24-S30.

Cancer Research UK: Possible symptoms of cancer. [http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/about-cancer/causes-symptoms/possible-symptoms-of-cancer]

Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E: Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010, 46 (4): 765-781.

Breslow RA, Sorkin JD, Frey CM, Kessler LG: Americans’ knowledge of cancer risk and survival. Prev Med. 1997, 26 (2): 170-177.

Gebhardt C, Rose N, Mitte K: Fact or artefact: an item response theory analysis of median split based repressor classification. Br J Health Psychol. 2014, 19 (1): 36-51.

MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD: On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002, 7 (1): 19-40.

Ekholm O, Gundgaard J, Rasmussen NK, Hansen EH: The effect of health, socio-economic position, and mode of data collection on non-response in health interview surveys. Scand J Public Health. 2010, 38 (7): 699-706.

Viswanath K, Breen N, Meissner H, Moser RP, Hesse B, Steele WR, Rakowski W: Cancer knowledge and disparities in the information age. J Health Commun. 2006, 11 (Suppl 1): 1-17.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/581/prepub

Acknowledgements

The study was supported financially by the Danish Cancer Society, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Faculty of Health at Aarhus University, the Tryg Foundation (J.no. 7-11-1339), the Danish Health and Medicines Authority and the Research Centre for Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care (CaP) at Aarhus University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AFP, CNW and PV conceived the study. All authors contributed to the design of the study and in its data collection. LH performed the statistical analyses in consultation with the other authors. LH drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to critically revising the paper. Finally, all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hvidberg, L., Pedersen, A.F., Wulff, C.N. et al. Cancer awareness and socio-economic position: results from a population-based study in Denmark. BMC Cancer 14, 581 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-581

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-581