Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of axitinib, a potent and selective second-generation inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3 in combination with pemetrexed and cisplatin was evaluated in patients with advanced non-squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

Overall, 170 patients were randomly assigned to receive axitinib at a starting dose of 5-mg twice daily continuously plus pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 on day 1 of up to six 21-day cycles (arm I); axitinib on days 2 through 19 of each cycle plus pemetrexed/cisplatin (arm II); or pemetrexed/cisplatin alone (arm III). The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Median PFS was 8.0, 7.9, and 7.1 months in arms I, II, and III, respectively (hazard ratio: arms I vs. III, 0.89 [P = 0.36] and arms II vs. III, 1.02 [P = 0.54]). Median overall survival was 17.0 months (arm I), 14.7 months (arm II), and 15.9 months (arm III). Objective response rates (ORRs) for axitinib-containing arms were 45.5% (arm I) and 39.7% (arm II) compared with 26.3% for pemetrexed/cisplatin alone (arm III). Gastrointestinal disorders and fatigue were frequently reported across all treatment arms. The most common all-causality grade ≥3 adverse events were hypertension in axitinib-containing arms (20% and 17%, arms I and II, respectively) and fatigue with pemetrexed/cisplatin alone (16%).

Conclusion

Axitinib in combination with pemetrexed/cisplatin was generally well tolerated. Axitinib combinations resulted in non-significant differences in PFS and numerically higher ORR compared with chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00768755 (October 7, 2008).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Currently, the majority of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) present with inoperable, locally advanced (stage IIIB) or metastatic (stage IV) disease for which no curative therapy is available, and the 5-year survival rate has remained ≤5% for the last few decades [1, 2]. In patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC without certain cytogenetic abnormalities (e.g. epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] mutations, anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK] translocations), platinum-based doublet chemotherapy remains the standard of care, albeit with modest efficacy [3], necessitating the search for additional treatment approaches to improve clinical outcomes. Because angiogenesis plays a critical role in tumor survival, growth, and metastasis, inhibition of the key angiogenesis pathway mediated via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor signaling, either at the ligand level (e.g. bevacizumab) or at the receptor level (e.g. the tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs] sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib, or axitinib, among many others), has been intensively evaluated in advanced NSCLC [4, 5]. Addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel and carboplatin was shown to improve overall survival (OS) compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC, providing evidence of therapeutic benefit in combining an antiangiogenic agent with chemotherapy [6]. However, the extent of survival gained from the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy may still be considered modest.

Axitinib is a potent and selective second-generation inhibitor of VEGF receptors 1, 2, and 3 [7] approved in the United States, European Union, Japan, and elsewhere for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure of one prior systemic therapy. Axitinib also showed promising single-agent activity with an acceptable safety profile in an open-label, single-arm, phase II trial in advanced NSCLC [8]. In treatment-naïve (n = 9) and previously treated (n = 23) patients with advanced NSCLC, objective response rate (ORR) was 9%, with median progression-free survival (PFS) and OS of 4.9 and 14.8 months, respectively. Common adverse events (AEs) included fatigue, anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, and hypertension. Axitinib was also generally well tolerated when administered in combination with standard chemotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumors, including NSCLC [9], which is the basis for the current study.

This study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combining axitinib with the pemetrexed/cisplatin regimen compared with pemetrexed/cisplatin alone in patients with advanced or recurrent non-squamous NSCLC. The choice of backbone chemotherapy was based on a large prospective phase III trial [10] that demonstrated OS superiority with better tolerability of pemetrexed/cisplatin over that of cisplatin/gemcitabine in NSCLC. In addition, axitinib was administered in two different dosing schedules (continuously vs. intermittently) to investigate whether a 2-day break in axitinib dosing just prior to chemotherapy administration would improve efficacy.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged 18 years and older (≥20 years in Japan) with histologically or cytologically confirmed stage IIIB with malignant pleural or pericardial effusion, stage IV, or recurrent non-squamous NSCLC were eligible. Additional inclusion criteria included at least one measurable target lesion as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.0); adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal function; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1; and no evidence of uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure [BP] >140/90 mmHg). Antihypertensive medications were allowed. Exclusion criteria included prior systemic therapy for stage IIIB or IV or recurrent NSCLC; prior treatment with a VEGF or VEGF-receptor inhibitor; lung lesion with cavitation, or invading or abutting a major blood vessel; hemoptysis (>2.5 mL in any 24-hr period) <2 weeks before enrollment; National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, v3.0) Grade 3 hemorrhage (from any cause) <4 weeks before enrollment; untreated central nervous system metastases; regular use of anticoagulants; or current use or anticipated need for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4-inhibiting or CYP3A4- or CYP1A2-inducing drugs. Each patient provided written informed consent before study entry.

Study design and treatment

This was a randomized, multicenter, open-label phase II study conducted in 37 centers in 11 countries, and the primary endpoint was PFS assessed by investigators. A non-randomized phase I lead-in (n = 10) evaluated the pharmacokinetics and safety of axitinib 5 mg oral dose twice daily (bid) given continuously with pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 administered once every 21 days [11].

In phase II, eligible patients were stratified by gender and ECOG PS (0 vs. 1) and, using a centralized, randomized permuted block allocation within strata generated by the central randomization administrator, assigned (1:1:1) to receive axitinib bid continuously plus pemetrexed/cisplatin (arm I), axitinib in a modified-dosing schedule plus pemetrexed/cisplatin (arm II), or pemetrexed/cisplatin alone (arm III). Axitinib was administered orally at a starting dose of 5 mg bid in 21-day cycles. For the modified-dosing schedule (arm II), axitinib was given on days 2 through 19, followed by a 3-day interruption (i.e. 2 days before and the day of chemotherapy), except the last cycle, during which it was given on days 2 through 21. Axitinib dose could be increased step-wise to 7 mg bid, and then to a maximum of 10 mg bid, in patients who tolerated axitinib with no treatment-related CTCAE Grade ≥3 AEs for ≥2 weeks, unless BP was greater than 150/90 mmHg or patient was taking antihypertensive medication. Axitinib dose was reduced step-wise to 3 mg bid, and then to 2 mg bid, at the discretion of the investigator, in patients who experienced a treatment-related CTCAE Grade 3 AE or BP >150/100 mmHg on maximal antihypertensive treatment. Axitinib treatment was temporarily interrupted in patients who had a treatment-related CTCAE Grade 4 AE, BP >160/105 mmHg, or urine protein/creatinine ratio ≥2.0 and restarted at the next lower dose once improved to CTCAE Grade ≤2, BP <150/100 mmHg, or urine protein/creatinine ratio <2.0, respectively. If a patient required a dose reduction below 2 mg bid, axitinib was to be discontinued. Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 were administered intravenously on day 1 of each of up to six 21-day cycles. Dose reductions were based on nadir hematologic counts or maximum non-hematologic toxicity from the preceding cycle. Vitamin B12 (1000 μg) and folic acid (350–1000 μg) were administered ≥1 week prior to treatment and then every 9 weeks and daily, respectively, until 3 weeks after the last dose of chemotherapy.

Patients randomized to arms I and II who completed four to six cycles of axitinib plus pemetrexed/cisplatin and had stable disease or better continued to receive single-agent axitinib maintenance therapy until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of patient consent. All patients were followed bimonthly for survival status following discontinuation of study treatment until at least 1 year after randomization of the last patient. Crossover between treatment arms was not allowed.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each center. The names of all institutional review boards and independent ethics committees are listed under Appendix. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00768755) on October 7, 2008.

Assessments

Radiologic tumor assessments were performed at screening and every 6 weeks thereafter, and whenever disease progression was suspected. Responses were evaluated according to RECIST and required confirmation ≥4 weeks after initial documentation. Safety was evaluated throughout the study. BP measurements were taken at screening and on day 1 of each cycle and thyroid function tests were conducted at screening and on day 1 of each chemotherapy cycle (cycles 1–6) and on day 1 of every other cycle thereafter. In addition, patients in arms I and II self-monitored BP bid at home prior to axitinib dosing and were instructed to contact their physicians for further evaluation of systolic BP >150 mmHg or diastolic BP >100 mmHg. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were evaluated, using the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) questionnaire on days 1 and 8 of each chemotherapy cycle and on day 1 of each axitinib maintenance cycle. MDSAI is a 19-item, validated self-reported questionnaire consisting of two scales that assess symptom severity and interference with different aspects of patient’s life [12]. Mean change in the MDASI score ≥0.98 point was defined as clinically meaningful.

Statistical analysis

The primary purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy (as measured by PFS) of axitinib in combination with pemetrexed/cisplatin versus pemetrexed/cisplatin alone in patients with non-squamous NSCLC in the randomized phase II study. The sample size estimates were based on separate comparisons of the axitinib-containing arms I and II versus arm III (pemetrexed/cisplatin alone). Fifty patients were required in each arm and 70 events for each comparison for a two-sample log-rank test to have an overall one-sided significance level of 0.20 and power of 0.80. This assumed a 50% improvement in median PFS from 5.0 months in arm III to 7.5 months in arm I or II, and ~12-month accrual time and 6-month follow-up. The hazard ratio and its 95% CI were estimated. A stratified log-rank test (one-sided, α = 0.20) was used to compare PFS between the treatment arms; however, the P values were for reference only.

Secondary endpoints included OS, ORR, duration of tumor response, PROs, and safety. ORR between treatment arms was compared using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by baseline ECOG PS and gender. Descriptive summary statistics (mean with standard deviation of absolute scores and mean change from baseline with 95% CI) of the MDASI items were reported. Safety was analyzed in patients who received at least one dose of study drug, and the results from only the randomized phase II portion were presented here.

The efficacy and safety analyses were originally conducted based on the data obtained as of March 1, 2011, while the study was still ongoing. PFS and overall safety were later updated using a data cutoff date of December 21, 2011, which are presented here. It should be noted that median PFS in each arm were very similar between the two analyses. The final analysis for OS, duration of tumor response among responders, number of deaths, and serious AEs was conducted after the database lock on May 18, 2012. For each endpoint, the most-up-to date results are presented in this manuscript.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 19, 2009 and April 21, 2010, a total of 170 patients were randomly assigned among three treatment arms: arm I (n = 55), arm II (n = 58), and arm III (n = 57; Figure 1). All patients were treated with assigned drugs, except two patients in arm III who did not receive pemetrexed/cisplatin. Among patients across the three treatment arms, the median age was similar (Table 1). The majority of patients were white (range, 71–84%) and male (range, 62–65%), and diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC (range, 84–91%). Smokers (both current and former) comprised 73%, 84%, and 79% of patients in arms I, II, and III, respectively.

Treatment

The median number of cycles for pemetrexed and cisplatin was similar across all treatment arms: five cycles each in arm I, six and five cycles, respectively, in arm II, and six cycles each in arm III. The median (range) of axitinib treatment cycles was 8 (1–28) in arm I and 6.5 (1–22) in arm II. Patients in arm I received axitinib treatment longer than those in arm II (median days on axitinib: 158 and 117 days, respectively). One or more axitinib dose interruptions were reported in 87% of patients in arm I and 97% in arm II, of which 76% and 69%, respectively, were due to AEs. Median relative axitinib dose intensity (defined as [total dose administered/total dose assigned] × 100) was 92% in arm I and 104% in arm II. Median relative dose intensity was similar between the three arms for pemetrexed (99%, 99%, and 100%) and for cisplatin (98%, 99%, and 100%). Following combination treatment, 58% of patients in arm I and 50% in arm II received single-agent axitinib maintenance therapy. By the completion of the study, all patients discontinued the study, mostly due to death (n = 116; Figure 1).

Efficacy

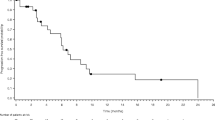

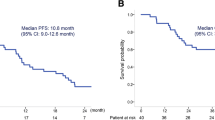

The investigator-assessed median (95% CI) PFS was 8.0 (6.5–10.0), 7.9 (6.2–9.5), and 7.1 (5.8–9.2) months in arms I, II, and III, respectively (Figure 2A). The hazard ratio (95% CI) was 0.89 (0.56–1.42; P = 0.36) for arm I versus arm III, and 1.02 (0.64–1.62; P = 0.54) for arm II versus arm III. Median OS (95% CI) was 17.0 (12.6–22.5), 14.7 (11.5–18.1), and 15.9 (11.1–not estimable) months in arms I, II, and III, respectively (Figure 2B). Overall confirmed ORRs (95% CI) was 45.5% (32.0–59.4) and 39.7% (27.0–53.4) for the axitinib-containing arms I and II, respectively, which were both higher than the 26.3% (15.5–39.7) in arm III (Table 2). Median (95% CI) duration of tumor response among responders was 7.8 (5.6–11.4), 6.7 (5.0–7.8), and 7.1 (4.2–24.7) months in arms I (n = 25), II (n = 23), and III (n = 15), respectively.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for (a) progression-free survival and (b) overall survival. P values were based on one-sided log-rank test stratified by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status and gender. Progression-free survival was based on data cutoff date of December 21, 2011 and overall survival was based on the most recent data at the time of final database lock on May 18, 2012. CI, confidence interval; Cont, continuously; HR, hazard ratio; mod, modified schedule; mOS, median overall survival; mPFS, median progression-free survival.

Safety

Gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, and constipation) and fatigue were common treatment-emergent, all-causality AEs in all three treatment arms (Table 3). Hypertension, diarrhea, and dysphonia occurred more frequently in axitinib-containing arms compared with pemetrexed/cisplatin alone. The most common Grade 3 AEs were hypertension in axitinib-containing arms (20% in arm I and 17% in arm II) and fatigue with pemetrexed/cisplatin alone (16%). Asthenia and pulmonary embolism were the only Grade 4 AEs observed in more than one patient in any arm (n = 2 each, arm II). Serious AEs reported by more than three patients in any arm were vomiting, nausea, and dehydration.

The majority of laboratory abnormalities reported during the study were Grade 1 or 2. Abnormal neutrophil count was the most common Grade 3/4 laboratory abnormality among all three treatment arms (Table 3). Hypothyroidism was reported infrequently (≤5%) in axitinib-containing arms, and no severe hemorrhagic events occurred in any treatment arm.

Patient-reported outcomes

At baseline, mean MDASI symptom severity (13-item summary) and interference scores (6-item summary) were similar among treatment arms (mean severity scores, 1.75, 2.09, and 1.80 and mean interference scores, 2.36, 2.97, and 2.64 in arms I, II, and III, respectively). Overall, there were statistical increases in both mean symptom severity and interference scores compared with baseline, indicating some clinically meaningful worsening of symptom severity and interference with patient feeling and function, in all three treatment arms. However, the majority of absolute symptom severity and interference scores remained <3.0 on a scale of 0 to 10.

Discussion

This study showed that axitinib, a selective antiangiogenic TKI targeting VEGF receptors, in combination with pemetrexed/cisplatin was generally well tolerated in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC. However, the study did not achieve its primary endpoint (PFS), irrespective of axitinib continuous or intermittent-dosing schedules. In addition, although combination therapy resulted in numerically higher ORR than chemotherapy alone, it did not improve OS.

While cross-study comparison is complicated due to many variables, median PFS and OS in patients treated with pemetrexed/cisplatin alone in this study were longer than the 4.8 and 10.3 months, respectively, observed in a prior large phase III trial of pemetrexed/cisplatin in chemotherapy-naïve NSCLC patients [10]. One plausible explanation is the selection of patients with non-squamous histology in the current study. Compared with the previous study [10], this study also had a higher percentage of Asians (21% vs. 13%), non-smokers (21% vs. 15%), and patients with ECOG PS 0 (47% vs. 35%), all of which have been identified as prognostic factors in advanced NSCLC [13]. Another possible explanation for longer survival in the control arm may be due to the subsequent therapies. Although the percentage of patients in this study who received any follow-up systemic therapy post-study, including EGFR inhibitors, was not too different from that reported for patients who received pemetrexed/cisplatin in the previous phase III trial [10] (47% compared with 52.6%, respectively), no data were available in either study to identify individuals with genomic mutations in EGFR or ALK, who would have benefited from the specific molecularly-targeted follow-up therapy. It should also be noted that clinical outcomes in a phase II study with a small number of patients do not always reflect the results of a subsequent phase III study, as seen with other agents.

Since the Sandler et al. [6] landmark study demonstrated significant survival benefits of adding bevacizumab to platinum doublet chemotherapy, several antiangiogenic TKIs have been evaluated in combination with cytotoxic agents, but with generally disappointing results [14–16]. In randomized phase III trials, addition of sorafenib to either paclitaxel/carboplatin in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC [14] or gemcitabine/cisplatin in advanced non-squamous NSCLC [16] did not meet the primary endpoint of OS. In another recent phase III trial, combination therapy with motesanib, another antiangiogenic TKI, plus paclitaxel/carboplatin also failed to prolong OS [15]. The current study of axitinib in combination with pemetrexed/cisplatin adds to a growing list of antiangiogenic TKIs that do not provide significant survival benefits when combined with standard doublet chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC, albeit with acceptable toxicity.

Reasons for apparent failure of antiangiogenic TKIs to improve efficacy of conventional chemotherapy are unclear, but are likely multifactorial and may include timing of administering antiangiogenic agents relative to cytotoxic agents, as well as off-target activities of antiangiogenic TKIs, adding to the toxicity. The potency of TKIs in inhibiting VEGF receptors determined in vitro may not necessarily translate to better efficacy in combination with cytotoxic agents. It is postulated that bevacizumab induces normalization of the tumor vasculature, thereby facilitating uptake of cytotoxic agents [17, 18]. In contrast, combination axitinib plus cyclophosphamide resulted in decreased tumor uptake of activated cyclophosphamide (4-hydroperoxy-cyclophosphamide) and decreased antitumor efficacy in a preclinical study [19]. Based on [18F]fluorodeoxythymidine (FLT) positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging, continuous administration of axitinib in patients with advanced solid tumors appears to reduce the tumor uptake of FLT, which is reverted to baseline following axitinib dosing interruption [20, 21]. Reduced FLT uptake could indicate decreased tumor proliferation, but also decreased cytotoxic drug delivery to the tumor, which would reduce the activity of cytotoxic agents. In the current study, it was hoped that stopping axitinib administration 2 days before and on the day of chemotherapy would alleviate the latter effect of axitinib, but no improvement in efficacy was observed. Clearly, there is an urgent need for better understanding of the complex nature of tumor angiogenesis and how axitinib and other antiangiogenic TKIs affect not only the tumor vasculature but also various cellular components within the tumor microenvironment [22].

With regard to toxicity, addition of axitinib to standard doses of pemetrexed and cisplatin did not lead to AEs that were unexpected, based on studies with single-agent axitinib [8] or pemetrexed/cisplatin alone [10] in advanced NSCLC. Compared with chemotherapy alone, incidence of hypertension increased substantially in patients receiving axitinib-containing treatment, which has been observed with antiangiogenic agents in general [16, 23, 24]. In the current axitinib-containing arms, no severe hemorrhagic incidence was reported.

Therefore, axitinib in combination with pemetrexed/cisplatin was generally tolerable and AEs were manageable in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Addition of axitinib resulted in numerically higher ORR, but did not improve PFS or OS compared with chemotherapy alone. However, it remains to be seen if certain subsets of patients may derive some benefits from the use of TKIs, including axitinib, as reported for other TKIs in patients with genomic abnormalities such as EGFR mutations [25–27], crizotinib in ALK-positive NSCLC [28], or in preclinical studies involving RET proto-oncogene rearrangements [29, 30].

Conclusions

In patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC, axitinib in combination with pemetrexed plus cisplatin was generally well tolerated and resulted in numerically higher ORR compared with chemotherapy alone. However, addition of axitinib — continuous dosing or with a 3-day break around the time of chemotherapy — did not improve PFS (primary endpoint) or OS over chemotherapy alone.

Appendix

The names of all institutional review boards and independent ethics committees were: Comitato Etico Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria San Luigi Gonzaga di Orbassano (Orbassano, Italy); Comitato Etico dell’IRCCS Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro di Genova (Genova, Italy); Comitato Etico Locale per la Sperimentazione Clinica della AUSL 12 di Viareggio (Camaiore, Italy); Shizuoka Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (Shizuoka, Japan); Komisja Bioetyczna przy Okregowej Izbie Lekarskiej w Gdansku (Gdansk, Poland); Academia de Stiinte Medicale, Comisia Nationala de Etica pentru Studiul Clinic al Medicamentului (Bucuresti, Romania); Ethics Committee at the Federal Service on Surveillance in Healthcare and Social Development (Moscow, Russian Federation); Ethics Committee of RUSSIAN ONCOLOGICAL RESEARCH CENTER n.a. N.N. BLOKHIN RAMS (Moscow; Russian Federation); Ethics Committee Saint-Petersburg State Medical University named after I.P. Pavlov of Roszdrav (Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation); Ethics Council at the Ministry of Healthcare and Social Development of Russian Federation (Moscow, Russian Federation); Ethics Committee of the Medical Military Academy named after S.M. Kirov (Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation); Local Ethics Committee of the Pyatigorsk Oncology Center (Pyatigorsk, Russian Federation); University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (Johannesburg, South Africa); Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation (Madrid, Spain): Ethikkommission beider Basel EKBB (Basel, Switzerland); Comitato Etico Cantonale c/o Sezione sanitaria (Bellinzona, Switzerland); Veterans General Hospital-Taipei Institutional Review Board Medical Research and Education (Taipei, Taiwan); Chung Shan Medical University Hospital Institutional Review Board (Taichung, Taiwan); National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Taipei, Taiwan); Taichung Veterans General Hospital Institutional Review Board (Taichung, Taiwan); Central Committee for Ethics Issues of Ministry of Health of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine); Local Committee for Ethics Issues of Kyiv City Clinical Oncologic Center (Kyiv, Ukraine); Committee for Ethics Issues at Dnipropetrovsk City Multiple-Discipline Clinical Hospital #4 (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine); Commission for Ethics Issues of Cherkasy Regional Oncology Dispensary (Cherkasy, Ukraine); South West - Exeter South West Research Ethics Committee Centre (Bristol, UK); Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board Incorporated (Cincinnati, OH, USA); Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects (SCRIHS) (Springfield, IL, USA); Penn State College of Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Hershey, PA, USA); Peoria Institutional Review Board (Peoria, IL, USA).

Authors’ information

Sinil Kim was employed at Pfizer Inc at the time of the study described here and development of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- bid:

-

Twice daily

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CTCAE:

-

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- CYP:

-

Cytochrome P450

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FLT:

-

[18F] fluorodeoxythymidine

- MDASI:

-

M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PROs:

-

Patient-reported outcomes

- RECIST:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

Cancer facts & figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2012. [http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf]

Wang T, Nelson RA, Bogardus A, Grannis FW: Five-year lung cancer survival: which advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer patients attain long-term survival?. Cancer. 2010, 116: 1518-1525. 10.1002/cncr.24871.

Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group: Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 92-98. 10.1056/NEJMoa011954.

Xiao YY, Zhan P, Yuan DM, Liu HB, Lv TF, Song Y, Shi Y: Chemotherapy plus multitargeted antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy alone in advanced NSCLC: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013, 69: 151-159. 10.1007/s00228-012-1333-3.

Ellis PM, Al-Saleh K: Multitargeted anti-angiogenic agents and NSCLC: clinical update and future directions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012, 84: 47-58. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.02.004.

Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH: Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 2542-2550. 10.1056/NEJMoa061884.

Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, Hallin ME, Wickman GR, Amundson K, Chen JH, Rewolinski DA, Yamazaki S, Wu EY, McTigue MA, Murray BW, Kania RS, O’Connor P, Shalinsky DR, Bender SL: Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 7272-7283. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0652.

Schiller JH, Larson T, Ou SH, Limentani S, Sandler A, Vokes E, Kim S, Liau K, Bycott P, Olszanski AJ, von Pawel J: Efficacy and safety of axitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 3836-3841. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8355.

Kozloff MF, Martin LP, Krzakowski M, Samuel TA, Rado TA, Arriola E, De Castro Carpeño J, Herbst RS, Tarazi J, Kim S, Rosbrook B, Tortorici M, Olszanski AJ, Cohen RB: Phase I trial of axitinib combined with platinum doublets in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and other solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2012, 107: 1277-1285. 10.1038/bjc.2012.406.

Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M, Lee JS, Mellemgaard A, Park K, Patil S, Rolski J, Goksel T, de Marinis F, Simms L, Sugarman KP, Gandara D: Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 3543-3551. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375.

Tortorici MA, Iglesias L, Kozloff MF, Pithavala YK, Ingrosso A, Belani CP: Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of coadministration of axitinib and pemetrexed/cisplatin (pem/cis) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [abstract PI-69]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012, 91 (Suppl 1): S33-

Cleeland CS: The M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory User Guide [Draft]. Houston, Texas, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. 2010, Houston, TX: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, [http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/departments-and-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/MDASI_userguide.pdf]

Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, Krzakowski M, Ramlau R, Vynnychenko I, Park K, Eberhardt WE, de Marinis F, Heeger S, Goddemeier T, O’Byrne KJ, Gatzemeier U: Prognostic factors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: data from the phase III FLEX study. Lung Cancer. 2012, 77: 376-382. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.03.010.

Scagliotti G, Novello S, von Pawel J, Reck M, Pereira JR, Thomas M, Abrao Miziara JE, Balint B, de Marinis F, Keller A, Aren O, Csollak M, Albert I, Barrios CH, Grossi F, Krzakowski M, Cupit L, Cihon F, Dimatteo S, Hanna N: Phase III study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 1835-1842. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321.

Scagliotti GV, Vynnychenko I, Park K, Ichinose Y, Kubota K, Blackhall F, Pirker R, Galiulin R, Ciuleanu TE, Sydorenko O, Dediu M, Papai-Szekely Z, Banaclocha NM, McCoy S, Yao B, Hei YJ, Galimi F, Spigel DR: International, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase III study of motesanib plus carboplatin/paclitaxel in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: MONET1. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 2829-2836. 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4987.

Paz-Ares LG, Biesma B, Heigener D, von Pawel J, Eisen T, Bennouna J, Zhang L, Liao M, Sun Y, Gans S, Syrigos K, Le Marie E, Gottfried M, Vansteenkiste J, Alberola V, Strauss UP, Montegriffo E, Ong TJ, Santoro A, NSCLC [non-small-cell lung cancer] Research Experience Utilizing Sorafenib (NExUS) Investigators Study Group: Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of gemcitabine/cisplatin alone or with sorafenib for the first-line treatment of advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 3084-3092. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7646.

Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Sims TL, Fraga CH, Ng CY, Rajasekeran S, Hagedorn NL, McCarville MB, Stewart CF, Davidoff AM: Bevacizumab-induced transient remodeling of the vasculature in neuroblastoma xenografts results in improved delivery and efficacy of systemically administered chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 3942-3950. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0278.

Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, Jain RK: Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev. 2011, 91: 1071-1121. 10.1152/physrev.00038.2010.

Ma J, Waxman DJ: Modulation of the antitumor activity of metronomic cyclophosphamide by the angiogenesis inhibitor axitinib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008, 7: 79-89.

Hoh C, Infante JR, Burris HA, Tarazi JC, Kim S, Rosbrook B, Reid TR: Axitinib inhibition of [18F] fluorothymidine (FLT) uptake in patients (pts) with colorectal cancer (CRC): implications for cytotoxic chemotherapy combinations [abstract 3591]. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (Suppl): 15s-

Jeraj R, Liu G, Simoncic U, Vanderhoek M, Perlman S, Alberti DB, Harrison MR, Wilding G: Concurrent assessment of vasculature and proliferative pharmacodynamics in patients treated with VEGFR TKI [abstract 3050]. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28 (Suppl): 15s-

Joyce JA: Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2005, 7: 513-520. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.024.

Dahlberg SE, Sandler AB, Brahmer JR, Schiller JH, Johnson DH: Clinical course of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients experiencing hypertension during treatment with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel on ECOG 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 949-954. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4482.

Rini BI, Schiller JH, Fruehauf JP, Cohen EE, Tarazi JC, Rosbrook B, Bair AH, Ricart AD, Olszanski AJ, Letrent KJ, Kim S, Rixe O: Diastolic blood pressure as a biomarker of axitinib efficacy in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17: 3841-3849. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2806.

Mok TSK, Paz-Ares L, Wu Y-L, Novello S, Juhasz E, Aren O, Sun Y, Hirsh V, Smit EF, Lathia C, Ong TJ, Pena C: Association between tumor EGFR and KRas mutation status and clinical outcomes in NSCLC patients randomized to sorafenib plus best supportive care (BSC) or BSC alone: subanalysis of the phase III MISSION trial [abstract LBA9_PR]. Ann Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl 9): ixe1-

Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, Naoki K, Sasaki H, Fujii Y, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Johnson BE, Meyerson M: EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004, 304: 1497-1500. 10.1126/science.1099314.

Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczesna A, Juhasz E, Esteban E, Molinier O, Brugger W, Melezinek I, Klingelschmitt G, Klughammer B, Giaccone G, SATURN investigators: Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11: 521-529. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1.

Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou SH, Dezube BJ, Janne PA, Costa DB, Varella-Garcia M, Kim WH, Lynch TJ, Fidias P, Stubbs H, Engelman JA, Sequist LV, Tan W, Gandhi L, Mino-Kenudson M, Wei GC, Shreeve SM, Ratain MJ, Settleman J, Christensen JG, Haber DA, Wilner K, Salgia R, Shapiro GI, Clark JW, et al: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 1693-1703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448.

Jeong WJ, Mo JH, Park MW, Choi IJ, An SY, Jeon EH, Ahn SH: Sunitinib inhibits papillary thyroid carcinoma with RET/PTC rearrangement but not BRAF mutation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011, 12: 458-465. 10.4161/cbt.12.5.16303.

Henderson YC, Ahn SH, Kang Y, Clayman GL: Sorafenib potently inhibits papillary thyroid carcinomas harboring RET/PTC1 rearrangement. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 4908-4914. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1772.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/290/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Pemetrexed was provided by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Authors thank Rebecca Miller, RN, and Linda Farling, RN, NP, of Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute for their contribution, Patrizia de Besi, Milan, Italy, for her critical role in reviewing and cleaning of clinical data, and Connie Chen, Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA, for critically reviewing the section on patient-reported outcomes. Medical writing support was funded by Pfizer Inc and was provided by Mariko Nagashima, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions (Southport, CT, USA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

CPB, NY, IMB, AP, and SN declare no relevant financial conflicts of interest. JT, PB, AGN, and AI are employees of and own stock in Pfizer Inc. SK, employed at Pfizer Inc at the time of the study described here and development of this manuscript is currently employed by Mirna Therapeutics and owns stock in Pfizer Inc and Mirna Therapeutics. GVS received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer Inc.

Authors’ contributions

CPB, PB, AGN, and SK contributed to the conception and design of the study. NY, IMB, AP, AGN, SK, and GVS collected and assembled data. SN, JT, PB, AGN, AI, SK, and GVS undertook the data analysis and interpretation. All authors participated in the development of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Belani, C.P., Yamamoto, N., Bondarenko, I.M. et al. Randomized phase II study of pemetrexed/cisplatin with or without axitinib for non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 14, 290 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-290

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-290