Abstract

Background

Extraneural metastases (ENM) rarely occur in medulloblastoma (MBL) patients and only few cases of subcutaneous localizations have been described. ENM indicate an aggressive disease associated with a worse prognosis. The characterization of metastatic tumours might be useful to understand their pathogenesis and to identify the most appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Case presentation

We present the case of a child with Large Cell Anaplastic (LC/A) MBL, who developed multiple subcutaneous metastases in the scalp area after a ventriculo-peritoneal shunting procedure. The disease rapidly progressed and the child died despite chemotherapy and primary tumour surgical debulking.

We molecularly classified the tumour as a group 3 MBL; in addition, we derived stem-like cells (SLC) from a metastatic lesion. Primary tumour, metastases and SLC were further analysed, particularly focusing on features linked to the cutaneous dissemination. Indeed, molecules involved in angiogenesis, cell invasion and epidermal growth factor signalling resulted highly expressed.

Conclusions

The present report describes a very rare case of subcutaneous metastatic MBL. The tumour, metastases and SLC have been clinically, pathologically and molecularly characterized. Our case is an example of multidisciplinary approach aiming to characterize MBL aggressive behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

MBL is the most common malignant brain tumour of childhood, accounting for approximately 15-20% of central nervous system (CNS) malignancies [1]. Despite multimodal therapy, 20% to 30% of MBL recur [2]. Large cell/anaplastic (LC/A) variant is most commonly associated with metastatic disease [3]. Brain and spine secondary localizations are frequent, while extraneural metastases (ENM) are rare (<10% of cases) and occur mostly in bone, lymph nodes, lung and liver [4]. Subcutaneous ENM have been described in very few cases [5, 6].

In recent years, high-throughput studies [7–14] allowed to classify MBL into four subgroups (WNT, SHH-Sonic Hedgehog, Group 3 and Group 4) and revealed the existence of gene mutations and of expression patterns linked to a worse prognosis.

Here we report the case of a child affected by LC/A MBL who developed subcutaneous metastases after a ventriculo-peritoneal shunting procedure. We performed histological and molecular analysis to characterize in details this aggressive tumour, particularly focusing on the stem-like cell population.

Methods

Histology: Paraffin-embedded 3-μm-thick sections from MBL tumour sample were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histology was reviewed by 2 neuropathologists (F.G. and M.A.) and diagnosis was centralized to minimize inter-observer variability.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Monoclonal antibody to p53 (DO-7; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA; dilution 1:300), and polyclonal anti-Beta catenin antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA, USA; dilution 1:100) were used.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH): Tumour tissue sections were deparaffinised and pre-treated with pepsin before hybridization with c-myc and control (centromere of chromosome 8) probes (Abnova Corporation, Taipei, Taiwan).

Stem-like cells (SLC) culture: Cells were isolated as previously reported [15]. Briefly, fresh tumour was dissociated to single cell suspension and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 0.6% glucose, 25 mg/ml insulin, 60 mg/ml N-acetyl-L-cystein, 2 mg/ml heparin, 20 ng/ml EGF, 20 ng/ml bFGF, 1× penicillin-streptomycin and B27 supplement without vitamin A.

Immunofluorescence: Immunofluerescence was performed as previously described [15]. Primary antibodies used were anti-Sox2 (MAB4343 Millipore) and anti-Nestin (ab6142; Abcam).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and gene expression analysis: RNA extraction, reverse transcription and gene expression analysis were performed as previously described [16]. RNA from normal cerebella were purchased from Life Technologies. TaqMan Low Density Array was custom designed with TaqMan assays for genes of interest [17, 18]. 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed using High capacity cDNA reverse transcription Kit (Ambion- Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Gene expression analysis on samples was performed employing an ABI Prism 7900 HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems- Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Transcripts quantification was expressed in arbitrary units as the ratio of the sample quantity to the calibrator or to the mean values of control samples. All values were normalized to the 4 endogenous gene controls: GAPDH, ß- ACTIN, ß2-MICROGLOBULIN and HPRT. Heat maps were generated employing SpotFire software according to Delta Ct values, as previously described [19].

Cytofluorimetry: Samples were dissociated into single cells and incubated with APC-conjugated anti-CD133 or with isotype control (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Ethics Committee of Bambino Gesù Children Hospital approved the case study.

Case presentation

Patient’s history and clinical features

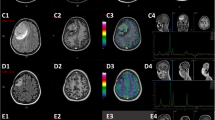

A 5 years old male with a recent history of MBL was referred to Hematology/Oncology Department of the Bambino Gesù Children Hospital for obstructive hydrocephalus. A partial resection of MBL had been performed at another institution 20 days earlier. After surgery, MRI revealed a surgical residue associated with a diffuse supra- and infratentorial meningeal involvement (Figure 1A and B) and associated hydrocephalus. Shortly after admission, an endoscopic third ventriculostomy was performed and converted to a ventriculo-peritoneal shunting procedure for intra-operative absence of significant cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow through the stoma. CSF resulted positive for neoplastic cells (Figure 1C). The histological revision of the primary lesion confirmed the diagnosis of MBL, variant LC/A (Figure 1D). The tumour resulted negative for nuclear Beta-Catenin (Figure 1E) and positive for p53 staining (Figure 1F). Moreover, c-myc amplification was detectable by fluorescent in situ hybridization (Figure 1G). Systemic chemotherapy based on carboplatin, etoposide and ifosfamide associated with intrathecal topotecan was immediately started and autologous hematopoietic stem cells were harvested after the first cycle. Clinical improvement with recovery of consciousness and disappearance of neoplastic cells in CSF was documented after the first 2 cycles. After the third cycle, the child’s clinical conditions rapidly worsened with progressive neurologic deterioration and occurrence of multiple solid woody masses in the scalp and posterior neck areas (Figure 1H). Surgical debulking was performed, revealing a diffuse infiltration of muscular, fascial and subcutaneous layers of the posterior neck (Figure 1I) and histological examination confirmed the primary diagnosis. The child rapidly progressed and died few days after surgery.

Radiological and histological features of MBL. (A) Post-gadolinium axial MR images show pseudonodular area of contrast-enhancement consistent with cerebellar neoplastic residual (arrow). (B) Post-gadolinium sagittal MR images show abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement (arrows) along the ventral surface of the mid-brain, cerebellar fissures and cerebral sulci due to leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. (C) Cerebrospinal fluid cytology shows the presence of large sized neoplastic cells that appear either singly or in clusters with rosette formation. (D) Hematoxylin&eosin staining of the primary lesion showing the presence of neoplastic cells large in size with marked anaplasia and large nuclei with evident nucleoli. Cell wrapping and necrotic phenaomena are also present (arrows). (E) Beta-Catenin immunohistochemical evaluation showing membrane and cytoplasmic positivity for beta-catenin with a negative nuclear staining. (F) p53 protein is overexpressed by neoplastic cells. (G) c-myc oncogene amplification (red spots) detected in neoplastic nuclei (blue) and centromere 8 signals (green spots) using CEP8/BAC as FISH probes. The white box highlights a nucleus in detail where 10 red spots are coupled with two green spots. (H) Coronal reformatted CT scan shows two subcutaneous metastases (arrows) with intact underlying calvarial bone. (I) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows voluminous extracranial metastases on the edge of the collection at the site of the former sub-occipital craniotomy, with fascial and muscular infiltration.

Molecular features of tumour, metastases and stem-like cells

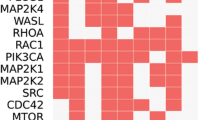

RNA was extracted and retro-transcribed from fresh primary tumour and subcutaneous metastases (neck and scalp). cDNA was analysed on a custom microfluid card with a panel of genes specific for MBL molecular subgroups [17, 18]. Over-expression of c-MYC, NRP3, NRL, GABRA5, IMPG2, MAB21L2 and OTX2 was suggestive of a molecular Group 3 for all samples analysed (Figure 2A). To shed light on the potential molecular mechanisms involved in the aggressive behaviour of MBL here described, we isolated its stem cell component (SLC) from neck metastasis. Bulk tumour population harboured CD133 positive cells (11%) (Figure 2B) which were enriched up to 52% in the derived neurospheres (Figure 2D-E). The stem like nature of these cells was further supported by Nestin and SOX2 protein expression (Figure 2F).

Molecular characteristics of MBL and derived stem like cells. (A) Heat map showing mRNA levels of the indicated genes in primary MBL (pMBL), scalp (M1) and neck (M2) metastases compared to normal cerebella (average of n = 8) as control (CTRLs). Genes are grouped depending on the molecular subgroups, which they identify (SHH, WNT, GROUP-3, GROUP-4). A green-red colour scale depicts normalized Delta Ct values (green, lower expression, red, higher expression). (B-C) Flow cytometry analysis (FACS) of CD133 in the starting population from neck metastasis (hMED bulk) (B) and after 14 days of culture (C) (isotypic control not shown). P3 shows percentage of positive cells while P4 shows percentage of negative cells. (D) Representative bright field image of neurospheres derived from neck metastasis after 14 days of culture. (E) Histograms showing mRNA levels of CD133 in MBL-neck metastasis (bulk) and in its derived SLC compared to normal cerebella as control (CTRLs). (F) Immunofluorescence staining with anti-Nestin and anti-Sox2 (green), Hoechst staining (blue) and merge of SLC. Scale bar = 5 μm for all panels. (G) Heat maps of expression levels of the indicated genes belonging to the highlighted categories in: pMBL, metastases (M1 and M2), in SLC derived from M2 and in normal adult cerebella as control (CTRLs). A green-red colour scale depicts normalized Delta Ct values (green, lower expression, red, higher expression).

We investigated molecular features linked to angiogenesis, cell invasion and epidermal growth factor receptors on the primary tumour (pMBL), metastases (M1 and M2) and SLC (Figure 2G). Most of the analysed genes were highly expressed in the primary lesion versus CTRLs; M1 and M2 had very similar gene expression patterns with some differences (e.g., NRP2 and ADAMs) with respect to pMBL. Interestingly, a higher expression of all analysed genes was detected in SLC (Figure 2G) compared to pMBL and metastases. Of note, high expression of both ERBB2 and ERBB4, among epidermal growth factor receptors, could have a role in the observed subcutaneous seeding (Figure 2G).

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) was also evaluated due to its reported correlation with aggressive MBL subgroups [20]. Indeed, it resulted overexpressed in all tumour samples as well as in SLC (Figure 2G) when compared to controls.

Conclusions

MBL is a heterogeneous disease with survival rates ranging from 85% for average risk patients to lower rates (<65%) in the presence of risk factors [21, 22]. The identification of MBL histological variant is critical for patient stratification: the presence of desmoplastic or of extensive nodular histology is a strong predictor for low risk disease in early childhood, while LC/A MBL has been associated with high risk and lower survival rates [3]. Indeed, LC/A MBL has been defined as a separate entity in the current WHO classification of CNS tumours [23].

Recently, Von Hoff suggested a better outcome for children with severe anaplastic histology without additional clinical and molecular risk factors (e.g. c-myc amplification, large cell histology, young age and metastases) [3]. Amplification of the proto-oncogene c-myc, a well-known negative prognostic marker for MBL, has been associated to LC/A variant and could contribute to its aggressive behaviour [24, 25]. Indeed, the frequency of c-myc amplification has been reported in about 5% of MBL in mixed cohorts [26], while a higher percentage has been reported in LC/A MBL [27]. Among the prognostic markers investigated to predict disease recurrence, only four have been confirmed as related to a poor outcome in a reproducible manner: p53, survivin, erbB-2 expression and amplification of myc genes [2]. In detail, p53 immunopositivity is an adverse prognostic marker [2, 28] and somatic TP53 mutations are associated with chemo- and radiotherapy resistance [2, 29]. A recent study showed that somatic TP53 mutations are enriched almost exclusively among SHH and WNT subgroup and are highly predictive of extremely poor survival in SHH MBL [30]. Presence of gross anaplasia and c-erbB-2 overexpression status are the most important predictors of recurrence rates [31].

Our patient showed adverse prognostic markers: severe anaplastic histology, c-myc amplification and p53 immunoreactivity. According to the subgroup classification [32], our patient was diagnosed as a group 3 (both for the primary tumour and the metastatic lesions), as expected from LC/A histology with c-myc amplification and with negative nuclear staining for Beta-Catenin. These histopathological features and biological properties might explain the occurrence of secondary localizations, including the early developed ENM.

Subcutaneous metastases have been reported in very few cases [5, 6]. Our clinical report is the first in a well-documented LC/A MBL. Differently from what previously described, our patient showed subcutaneous infiltration in the posterior neck region, far from the path of the ventriculo-peritoneal shunt. Moreover, in the final stages of the disease, a cobblestone appearance of the scalp suggested further dissemination of tumour.

Presence of VP shunt has been suggested as a risk factor for MBL metastases [33]; however, the general concept that systemic metastases are more frequent in patients with CSF shunts is not fully accepted [34].

Interestingly, stem cell signatures have been associated with a poor prognosis in tumours, raising the concept that the stem cell population may indeed contribute to the aggressive behaviour [35, 36]. Very recently, it has been reported that clonal genetic events observed in metastases can be demonstrated in a restricted sub-clone of the primary tumour, suggesting that only rare cells have the ability to metastasize [37].

The opportunity to compare primary tumour with its metastases and SLC allowed us to highlight novel molecular findings. Our results are in agreement with the disease model based on different compartments: metastases were very similar among each other, while showing some differences versus the primary MBL. Differences were more evident between tumour samples and stem like cells.

Neoangiogenesis and cell invasion molecules were highly expressed in tumour bulk and even more in SLC. The same pattern was observed for the expression levels of molecules involved in EGF signalling, that may be linked to the occurrence of subcutaneous seeding.

In the era of molecular characterization of tumours, the identification of biological mechanisms of aggressiveness might well contribute to develop the most appropriate therapeutic strategies. In the present clinical case, we have shown that both primary tumour cells and SLC express ERBB family members, supporting a possible use of anti-ERBB specific therapies, which are already available [38, 39]. In addition, our case expressed EZH2, a molecule that has been recently reported as a critical regulator in MBL growth, thus representing a novel potential therapeutic target [40].

In conclusion, we report a rare case of subcutaneous metastatic LC/A MBL, which was analysed in details through a multidisciplinary approach. The molecular characterization of these aggressive tumours might improve the understanding of their pathogenesis and provide the rationale for targeted therapeutic strategies.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this Case report and of any accompanying images.

References

Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C: CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 14 (Suppl 5): v1-v49. 10.1093/neuonc/nos218.

Tabori U, Baskin B, Shago M, Alon N, Taylor MD, Ray PN, Bouffet E, Malkin D, Hawkins C: Universal poor survival in children with medulloblastoma harboring somatic TP53 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28 (8): 1345-1350. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5952.

von Hoff K, Hartmann W, von Bueren AO, Gerber NU, Grotzer MA, Pietsch T, Rutkowski S: Large cell/anaplastic medulloblastoma: outcome according to myc status, histopathological, and clinical risk factors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010, 54 (3): 369-376. 10.1002/pbc.22339.

Mazloom A, Zangeneh AH, Paulino AC: Prognostic factors after extraneural metastasis of medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010, 78 (1): 72-78. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1729.

Galarza M, Sosa FP: Pure subcutaneous seeding from medulloblastoma. Pediatr Neurol. 2003, 29 (3): 245-249. 10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00215-7.

Maiti T, Sabharwal P, Pandey P, Devi BI: Subcutaneous metastasis in medulloblastoma: A case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2013, 8 (2): 168-170. 10.4103/1817-1745.117861.

Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, Taylor MD: The clinical implications of medulloblastoma subgroups. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012, 8 (6): 340-351. 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.78.

Northcott PA, Jones DT, Kool M, Robinson GW, Gilbertson RJ, Cho YJ, Pomeroy SL, Korshunov A, Lichter P, Taylor MD, Pfister SM: Medulloblastomics: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012, 12 (12): 818-834. 10.1038/nrc3410.

Jones DT, Jager N, Kool M, Zichner T, Hutter B, Sultan M, Cho YJ, Pugh TJ, Hovestadt V, Stutz AM, Rausch T, Warnatz HJ, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sturm D, Pleier S, Cin H, Pfaff E, Sieber L, Wittmann A, Remke M, Witt H, Hutter S, Tzaridis T, Weischenfeldt J, Raeder B, Avci M, Amstislavskiy V, Zapatka M, Weber UD, et al: Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012, 488 (7409): 100-105. 10.1038/nature11284.

Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, Pomeranz Krummel DA, Auclair D, Bochicchio J, Carneiro MO, Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Erlich RL, Greulich H, Lawrence MS, Lennon NJ, McKenna A, Meldrim J, Ramos AH, Ross MG, Russ C, Shefler E, Sivachenko A, Sogoloff B, Stojanov P, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP, Amani V, Teider N, Sengupta S, Francois JP, Northcott PA, Taylor MD, et al: Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations. Nature. 2012, 488 (7409): 106-110. 10.1038/nature11329.

Cho YJ, Tsherniak A, Tamayo P, Santagata S, Ligon A, Greulich H, Berhoukim R, Amani V, Goumnerova L, Eberhart CG, Lau CC, Olson JM, Gilbertson RJ, Gajjar A, Delattre O, Kool M, Ligon K, Meyerson M, Mesirov JP, Pomeroy SL: Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (11): 1424-1430. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5148.

Northcott PA, Shih DJ, Peacock J, Garzia L, Morrissy AS, Zichner T, Stutz AM, Korshunov A, Reimand J, Schumacher SE, Beroukhim R, Ellison DW, Marshall CR, Lionel AC, Mack S, Dubuc A, Yao Y, Ramaswamy V, Luu B, Rolider A, Cavalli FM, Wang X, Remke M, Wu X, Chiu RY, Chu A, Chuah E, Corbett RD, Hoad GR, Jackman SD, et al: Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes. Nature. 2012, 488 (7409): 49-56. 10.1038/nature11327.

Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Witt H, Hielscher T, Eberhart CG, Mack S, Bouffet E, Clifford SC, Hawkins CE, French P, Rutka JT, Pfister S, Taylor MD: Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (11): 1408-1414. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4324.

Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC, Eberhart CG, Parsons DW, Rutkowski S, Gajjar A, Ellison DW, Lichter P, Gilbertson RJ, Pomeroy SL, Kool M, Pfister SM: Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123 (4): 465-472. 10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z.

Po A, Ferretti E, Miele E, De Smaele E, Paganelli A, Canettieri G, Coni S, Di Marcotullio L, Biffoni M, Massimi L, Di Rocco C, Screpanti I, Gulino A: Hedgehog controls neural stem cells through p53-independent regulation of Nanog. EMBO J. 2010, 29 (15): 2646-2658. 10.1038/emboj.2010.131.

Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Po A, Di Marcotullio L, Tosi E, Espinola MS, Di Rocco C, Riccardi R, Giangaspero F, Farcomeni A, Nofroni I, Laneve P, Gioia U, Caffarelli E, Bozzoni I, Screpanti I, Gulino A: MicroRNA profiling in human medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2009, 124 (3): 568-577. 10.1002/ijc.23948.

Schwalbe EC, Lindsey JC, Straughton D, Hogg TL, Cole M, Megahed H, Ryan SL, Lusher ME, Taylor MD, Gilbertson RJ, Ellison DW, Bailey S, Clifford SC: Rapid diagnosis of medulloblastoma molecular subgroups. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17 (7): 1883-1894. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2210.

Northcott PA, Shih DJ, Remke M, Cho YJ, Kool M, Hawkins C, Eberhart CG, Dubuc A, Guettouche T, Cardentey Y, Bouffet E, Pomeroy SL, Marra M, Malkin D, Rutka JT, Korshunov A, Pfister S, Taylor MD: Rapid, reliable, and reproducible molecular sub-grouping of clinical medulloblastoma samples. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123 (4): 615-626. 10.1007/s00401-011-0899-7.

Miele E, Buttarelli FR, Arcella A, Begalli F, Garg N, Silvano M, Po A, Baldi C, Carissimo G, Antonelli M, Spinelli GP, Capalbo C, Donofrio V, Morra I, Nozza P, Gulino A, Giangaspero F, Ferretti E: High-throughput microRNA profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16 (2): 228-240. 10.1093/neuonc/not215.

Alimova I, Venkataraman S, Harris P, Marquez VE, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Taylor MD, Foreman NK, Vibhakar R: Targeting the enhancer of zeste homologue 2 in medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2012, 131 (8): 1800-1809. 10.1002/ijc.27455.

Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, Rorke-Adams L, Burger PC, Robertson PL, Bayer L, LaFond D, Donahue BR, Marymont MH, Muraszko K, Langston J, Sposto R: Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24 (25): 4202-4208. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980.

Gajjar A, Chintagumpala M, Ashley D, Kellie S, Kun LE, Merchant TE, Woo S, Wheeler G, Ahern V, Krasin MJ, Fouladi M, Broniscer A, Krance R, Hale GA, Stewart CF, Dauser R, Sanford RA, Fuller C, Lau C, Boyett JM, Wallace D, Gilbertson RJ: Risk-adapted craniospinal radiotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed medulloblastoma (St Jude Medulloblastoma-96): long-term results from a prospective, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7 (10): 813-820. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70867-1.

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P: The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 114 (2): 97-109. 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4.

Herms J, Neidt I, Luscher B, Sommer A, Schurmann P, Schroder T, Bergmann M, Wilken B, Probst-Cousin S, Hernaiz-Driever P, Behnke J, Hanefeld F, Pietsch T, Kretzschmar HA: C-MYC expression in medulloblastoma and its prognostic value. Int J Cancer. 2000, 89 (5): 395-402. 10.1002/1097-0215(20000920)89:5<395::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-V.

Stearns D, Chaudhry A, Abel TW, Burger PC, Dang CV, Eberhart CG: c-myc overexpression causes anaplasia in medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006, 66 (2): 673-681. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1580.

Aldosari N, Bigner SH, Burger PC, Becker L, Kepner JL, Friedman HS, McLendon RE: MYCC and MYCN oncogene amplification in medulloblastoma. A fluorescence in situ hybridization study on paraffin sections from the Children’s Oncology Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002, 126 (5): 540-544.

Eberhart CG, Kratz JE, Schuster A, Goldthwaite P, Cohen KJ, Perlman EJ, Burger PC: Comparative genomic hybridization detects an increased number of chromosomal alterations in large cell/anaplastic medulloblastomas. Brain Pathol. 2002, 12 (1): 36-44.

Woodburn RT, Azzarelli B, Montebello JF, Goss IE: Intense p53 staining is a valuable prognostic indicator for poor prognosis in medulloblastoma/central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumors. J Neurooncol. 2001, 52 (1): 57-62. 10.1023/A:1010691330670.

Pfister S, Remke M, Benner A, Mendrzyk F, Toedt G, Felsberg J, Wittmann A, Devens F, Gerber NU, Joos S, Kulozik A, Reifenberger G, Rutkowski S, Wiestler OD, Radlwimmer B, Scheurlen W, Lichter P, Korshunov A: Outcome prediction in pediatric medulloblastoma based on DNA copy-number aberrations of chromosomes 6q and 17q and the MYC and MYCN loci. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27 (10): 1627-1636. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9432.

Zhukova N, Ramaswamy V, Remke M, Pfaff E, Shih DJ, Martin DC, Castelo Branco P, Baskin B, Ray PN, Bouffet E, Von Bueren AO, Jones DT, Northcott PA, Kool M, Sturm D, Pugh TJ, Pomeroy SL, Cho YJ, Pietsch T, Gessi M, Rutkowski S, Bognar L, Klekner A, Cho BK, Kim SK, Wang KC, Eberhart CG, Fevre Montange M, Fouladi M, French PJ, et al: Subgroup-specific prognostic implications of TP53 mutation in medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31 (23): 2927-2935. 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5052.

Srikantha U, Balasubramaniam A, Santosh V, Somanna S, Bhagavatula ID, Ashwathnarayana CB: Recurrence in medulloblastoma - influence of clinical, histological and immunohistochemical factors. Br J Neurosurg. 2010, 24 (3): 280-288.

Remke M, Ramaswamy V, Taylor MD: Medulloblastoma molecular dissection: the way toward targeted therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013, 25 (6): 674-681. 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000008.

Muoio VM, Shinjo SO, Matushita H, Rosemberg S, Teixeira MJ, Marie SK: Extraneural metastases in medulloblastoma. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011, 69 (2B): 328-331. 10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300012.

Berger MS, Baumeister B, Geyer JR, Milstein J, Kanev PM, LeRoux PD: The risks of metastases from shunting in children with primary central nervous system tumors. J Neurosurg. 1991, 74 (6): 872-877. 10.3171/jns.1991.74.6.0872.

Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA: An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (5): 499-507. 10.1038/ng.127.

Shats I, Gatza ML, Chang JT, Mori S, Wang J, Rich J, Nevins JR: Using a stem cell-based signature to guide therapeutic selection in cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71 (5): 1772-1780. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1735.

Wu X, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Dupuy AJ, Shih DJ, Witt H, Croul S, Bouffet E, Fults DW, Eberhart CG, Garzia L, Van Meter T, Zagzag D, Jabado N, Schwartzentruber J, Majewski J, Scheetz TE, Pfister SM, Korshunov A, Li XN, Scherer SW, Cho YJ, Akagi K, MacDonald TJ, Koster J, McCabe MG, Sarver AL, Collins VP, Weiss WA, Largaespada DA, et al: Clonal selection drives genetic divergence of metastatic medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012, 482 (7386): 529-533. 10.1038/nature10825.

Meco D, Servidei T, Riccardi A, Ferlini C, Cusano G, Zannoni GF, Giangaspero F, Riccardi R: Antitumor effect in medulloblastoma cells by gefitinib: Ectopic HER2 overexpression enhances gefitinib effects in vivo. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11 (3): 250-259. 10.1215/15228517-2008-095.

Fouladi M, Stewart CF, Blaney SM, Onar-Thomas A, Schaiquevich P, Packer RJ, Goldman S, Geyer JR, Gajjar A, Kun LE, Boyett JM, Gilbertson RJ: A molecular biology and phase II trial of lapatinib in children with refractory CNS malignancies: a pediatric brain tumor consortium study. J Neurooncol. 2013, 114 (2): 173-179. 10.1007/s11060-013-1166-7.

Alimova I, Birks DK, Harris PS, Knipstein JA, Venkataraman S, Marquez VE, Foreman NK, Vibhakar R: Inhibition of EZH2 suppresses self-renewal and induces radiation sensitivity in atypical rhabdoid teratoid tumor cells. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 15 (2): 149-160.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/262/prepub

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge patient’s family for collaboration.

This work was partially supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Italian Ministry of University and Research (FIRB and PRIN), Italian Ministry of Health and Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EM, AP, GPS, RF, AG and EF carried out molecular studies. AM, FdB, GSC, AC and FL clinically followed the patient. MA, FRB, FG carried out pathologic assessments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Angela Mastronuzzi, Evelina Miele contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mastronuzzi, A., Miele, E., Po, A. et al. Large cell anaplastic medulloblastoma metastatic to the scalp: tumor and derived stem-like cells features. BMC Cancer 14, 262 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-262

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-262