Abstract

Background

Women with mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 are at high risk of developing breast cancer and, in British Columbia, Canada, are offered screening with both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mammography to facilitate early detection. MRI is more sensitive than mammography but is more costly and produces more false positive results. The purpose of this study was to calculate the cost-effectiveness of MRI screening for breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in a Canadian setting.

Methods

We constructed a Markov model of annual MRI and mammography screening for BRCA1/2 carriers, using local data and published values. We calculated cost-effectiveness as cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained (QALY), and conducted one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Results

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of annual mammography plus MRI screening, compared to annual mammography alone, was $50,900/QALY. After incorporating parameter uncertainty, MRI screening is expected to be a cost-effective option 86% of the time at a willingness-to-pay of $100,000/QALY, and 53% of the time at a willingness-to-pay of $50,000/QALY. The model is highly sensitive to the cost of MRI; as the cost is increased from $200 to $700 per scan, the ICER ranges from $37,100/QALY to $133,000/QALY.

Conclusions

The cost-effectiveness of using MRI and mammography in combination to screen for breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers is finely balanced. The sensitivity of the results to the cost of the MRI screen itself warrants consideration: in jurisdictions with higher MRI costs, screening may not be a cost-effective use of resources, but improving the efficiency of MRI screening will also improve cost-effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutations are at particularly high risk of breast cancer, with a 45-65% cumulative risk by age 70 years [1, 2]. In current practice at the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA), women with a strong family history of breast and ovarian cancer who meet specific eligibility criteria [3] may be referred to the Hereditary Cancer Program to receive genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1/2 mutations. Women with a BRCA1/2 mutation may significantly reduce their risk of breast cancer by opting to undergo prophylactic bilateral mastectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy [4–7], but many factors are involved in choosing risk-reducing surgery [8] and many women instead opt for early detection strategies, including regular screening with MRI and mammography [9]. Since 2003, the BCCA has operated a high-risk screening clinic, offering annual breast cancer screening with MRI and mammography to confirmed BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

MRI is more sensitive than mammography for breast cancer screening in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, with screening trials indicating that between 89-100% of breast cancers were detected with the combination of mammography and MRI, versus 33-50% with mammography alone [10–18]. However, the specificity of MRI is lower than mammography (73-80% for mammography and MRI vs. 91-99% for mammography alone [10–18]), giving rise to more false positive screens, which may increase costs and negatively impact quality of life for screening participants [19]. Breast MRI is more expensive than mammography, but there is little evidence available on the cost-effectiveness of MRI for breast cancer screening in Canada. Estimates from the United States of incremental cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) for the addition of MRI to annual mammography screening range widely, from $55,420/QALY [20] and $69,125/QALY [21] for BRCA1 carriers, $130,695/QALY BRCA2 carriers [20], and $179,599/QALY for women with >15% lifetime risk [22] (all values USD). Cost-effectiveness ratios are particularly sensitive to the unit cost of an MRI screening test [21–23] and to the breast cancer risk in the population being screened [20, 24]. In order to better understand the context of MRI screening at the BCCA, the investigators determined a local cost-effectiveness analysis was warranted. The objective of this study is to estimate the cost-effectiveness of annual mammography plus MRI screening for breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, as compared to screening with mammography alone, from the perspective of the British Columbia healthcare system, using local cost and outcomes data.

Methods

Model design

An advisory panel of clinicians, program managers and researchers was established to support this study. The investigators constructed a Markov model to determine the cost per QALY gained with current MRI and mammography screening practices, comparing annual mammography alone to annual mammography and MRI (Figure 1), from the perspective of the healthcare system. The model simulates a cohort of women beginning at age 25 years, with a 6-month cycle length, representing the current time between screens, and a lifetime time horizon. The model represents screening, diagnostics and treatment for a woman’s first breast cancer; screening for second primary cancers is not considered.

Markov model for annual breast cancer screening with MRI and Mammography. Women begin in the Markov stages “MRI screen” or “Mammography” and alternate every 6 months (in the mammography alone arm, the “MRI screen” state is replaced with a 6-month interval with no screen). Women with positive screening results move through the right side of the model; those with no cancer (false positives) return to screening, while cancer cases continue to treatment, by stage at diagnosis. Women with cancer whose screening results are negative (false negatives) are screened once more; if their cancer remains undetected they are classified as having non-screen-detected cancers, and proceed through treatment.

In the mammography plus MRI screening strategy, women alternate between MRI and mammography screening every six months (Figure 1). In current practice at the BCCA high-risk screening clinic, MRI is offered from ages 25–64 years, and mammography screening is offered from ages 30–79 years; thus in the mammography plus MRI strategy, women aged 25–29 years receive only MRI screening, and women 65–79 years receive only mammography. In the mammography alone strategy, women are screened with mammography annually from age 30–79 years. Women with cancer detected by screening (true positives) proceed through diagnostic work-up to treatment; women with false positive screen results also undergo a diagnostic work-up but return to screening. Any women with incident cancer that is not detected by screening remain in the screening health states for a further 6 months; if their cancer remains undetected (that is, if in the MRI arm their subsequent screen is also negative, or if in the mammography alone strategy they do not receive a screen within those 6 months), they are classified as having clinically manifesting non-screen-detected cancer.

Cancer treatments and outcomes by stage at diagnosis are the same across both strategies of the model. In the model, patients undergo treatment for the first 18 months following diagnosis, or until they die or transition to progressive disease, whichever is shorter. Patients who die of cancer within 18 months (3 cycles) of diagnosis transition to the ‘dead’ health state without moving through the ‘progressive disease’ state, while those who die in subsequent cycles are assumed to have experienced progressive disease for the last 18 months (3 cycles) prior to death [25]. In the model, patients with in situ disease do not progress to invasive disease, and all patients who survive at least 10 years after diagnosis are no longer at risk of progression.

Transition probabilities

Age-specific breast cancer incidence in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 populations [2] was weighted to represent mutation frequency at the BCCA (59% BRCA1 and 41% BRCA2; Table 1). Sensitivity and specificity values for the mammography plus MRI arm were taken from a meta-analysis of MRI screening effectiveness studies [16]. The sensitivity of MRI or mammography given a prior false negative screen with the opposite modality was calculated using the reported sensitivity values for each screening modality alone and the sensitivity of detection by either MRI or mammography when both are offered together. Using these values, we were able to solve for the joint probability of detection by both MRI and mammography, and derive estimates for the conditional probability of detection by MRI given a false negative from mammography, and vice versa. For the mammography alone strategy, age-specific sensitivity and specificity values were used [26] to account for the early onset of breast cancer among BRCA1/2 carriers and the decreased sensitivity of mammography in younger women. The stage distributions of MRI-detected and mammogram-detected cancers in the BRCA1/2 population were synthesized using Dirichlet distributions for stage at diagnosis [11–13, 27]. For clinically manifesting, non-screen-detected cancers, the historical stage distribution prior to screening was used [28]. In the model, stage distribution for screen-detected cancers was based only on method of detection, and was independent of prior screening.

Local survival rates for the general breast cancer population were calculated using data from the BC Cancer Registry (including linked deaths data from the BC Vital Statistics Agency), and were fitted to a series of Weibull distributions [29] by the Surveillance and Outcomes Unit of the BCCA to generate the transition probabilities for the cancer outcomes in the model. The advisory panel validated this decision; the literature suggests that survival among BRCA1/2 carriers with breast cancer is no worse than for mutation-free controls [30]. Transition through the progressive disease state before death, described above, was implemented by introducing an 18-month lead time to the calculated survival curves. Published estimates of competing mortality in the BRCA1/2 population were also incorporated into the model [31].

Costs

All costs included in the model are summarized in Table 2. The cost of mammography screening was estimated from the BC Medical Services Commission Fee Schedule for 2008 [32]. MRI screening cost was calculated as the mean of three cost estimates provided by the BCCA and two regional health authorities. The cost included radiologist, technologist and clerical staff costs, materials, support costs, and overhead. The cost of a diagnostic work-up was calculated as the weighted mean cost of consultations, diagnostic mammography, ultrasound, fine needle aspiration, core biopsy, and open biopsy delivered following abnormal screen results, using observed frequencies reported from the provincial screening program [33] and local unit cost estimates [32, 34].

We calculated treatment costs in the model using records from the BC Cancer Agency database (CAIS) for all breast cancer patients who underwent mutation testing at the Hereditary Cancer Program between 2002 and 2007 and were found to be BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers (n = 68). Surgery, radiotherapy and systemic therapy in the first 18 months following diagnosis were included in the cost calculation [32, 35–37] and fitted to gamma distributions [29]. Costs were calculated separately for three 6-month intervals (from months 1–6, 7–12, and 13–18 following diagnosis) to correspond with model cycle length and ensure appropriate allocation of costs over time. Using the subset of patients who died of breast cancer before January 2009 (n = 10) we calculated the cost of radiotherapy and systemic therapy received in the last 18 months of life (as three 6-month intervals), and estimated costs of additional hospitalization, using published length of stay and per-diem costs [36, 37].

Utilities

Standard gamble utility weights obtained from the literature for breast cancer treatment by stage at diagnosis were applied for up to 18 months while patients were in the cancer treatment states (Table 3) [38]. After 18 months a remission utility was applied to all cancer stages, until transition to progressive disease or return to full health after 10 years. The screening and interval health states were assumed to have a utility value of 1.0. The utility for a diagnostic workup was derived from a published value for diagnostic mammography, and lasted for two weeks of the 6 month cycle [39]. Utilities for remission and diagnostic mammography, which had been measured using a visual analog scale, were scaled up to approximate standard gamble values [39, 40].

Analysis

The model was analyzed using TreeAge Pro 2012, 1.3.0. The model design was clinically validated by members of the advisory panel, and model estimates of incidence and mortality were verified against published values. We conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis to calculate the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) of screening with MRI, expressed as 2008 CAD$ per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). Costs and utilities were discounted at 3.5% per year [41]. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis was conducted using Monte Carlo simulation techniques with 10,000 draws from the input distributions. Decision uncertainty was represented by plotting all results on the cost-effectiveness plane and by using the cost effectiveness acceptability curve, which illustrates the probability that MRI screening is cost-effective for a given range of willingness to pay values [29]. Cost-effectiveness was evaluated at example willingness to pay values of $50,000 and $100,000 per QALY. One-way sensitivity analysis was also conducted for the cost of MRI, sensitivity and specificity of MRI, stage of MRI-detected cancers, and discount rate to evaluate their impact on the ICER.

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of British Columbia-BC Cancer Agency Research Ethics Board.

Results

After modeling a BRCA1/2 cohort from age 25 years, the cumulative risk of developing breast cancer by age 65 years was 42.7% (95% CI: 38.8, 46.7) (Table 4). This was slightly lower but generally comparable to cumulative incidence estimated from Antoniou et al.[1] and Chen and Parmigiani [2] (50.4% and 45.4% respectively), and considered a valid approximation. Mortality was slightly reduced with the addition of MRI, with 80.1% (95% CI: 78.9, 81.1) vs. 79.1% (95% CI: 77.4, 80.4) of women surviving to age 65. Mortality approximated values from Byrd et al. [42]; using data from that study, an estimated 22% of female BRCA1/2 mutation carries died before age 65 years from breast cancer or other causes, excluding ovarian cancer.

With the addition of MRI to annual mammography screening, 93.9% (95% CI: 89.4, 97.3) of cancers that developed by age 65 years were screen-detected, compared to 71.7% (95% CI: 65.9, 77.2) with mammography alone. Cancers in the MRI plus mammography arm were less likely to be either regional or distant, and more likely to be localized than in the mammography alone arm.

Cost-effectiveness analysis gave an incremental cost of MRI screening of $4692 (95% CI: 3084, 7910) per participant, with 0.092 QALYs gained (95% CI: -0.027, 0.190), resulting in a mean ICER of $50,911/QALY (Table 4). The scatter plot of incremental cost and effectiveness values for each simulation is shown in Figure 2; in 3.9% of simulations, the MRI screening strategy was less effective than mammography alone. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Figure 3) indicates that if a decision maker were willing to pay $100,000 per QALY gained, MRI screening is a cost-effective option 85.6% of the time. At a willingness to pay of $50,000/QALY, it is cost-effective 52.6% of the time.

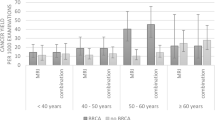

One-way sensitivity analysis indicated that the model was somewhat sensitive to changes in the effectiveness of MRI screening – measured as MRI sensitivity, MRI specificity and stage distribution of MRI-detected cancers – but very sensitive to the cost of an MRI scan (Figure 4). As cost was varied from $200-$700, the ICER ranged widely, from $37,119 to $132,944 per QALY.

Discussion

In our model, annual mammography plus MRI, compared to annual mammography alone, has an ICER of $50,900 per QALY. This ICER was estimated using local cost and treatment data, with input from clinicians and decision-makers on the project’s advisory panel, in an effort to most accurately depict the context of breast cancer screening and treatment for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in British Columbia. These results suggest that the cost-effectiveness of the MRI screening program for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers is finely balanced, with sensitivity to input parameters and statistical uncertainty. The BCCA does not use a cost-effectiveness threshold, but the ICER falls within the generally accepted range for funded programs.

The mammography plus MRI strategy of the model differs from the mammography alone strategy in four key ways: the cost of MRI screening, increased screening sensitivity, a more favourable stage distribution among MRI-detected cancers, and more false positive screens due to decreased screening specificity. The cost-effectiveness of MRI screening is highly dependent on the cost of an MRI scan, as indicated in one-way sensitivity analysis. In situations where MRI scans are costlier than at the BCCA, MRI screening for breast cancer may not be a cost-effective option. However, these results also suggest that improvements in technical efficiency leading to reductions in the per-scan cost of MRI may reduce the cost-effectiveness of MRI screening to more acceptable levels.

The time horizon of this model, as with any model of preventive or screening techniques, also has an impact on the findings. The costs of MRI screening accrue from the beginning of model, while the benefits arising from MRI screening, such as lower treatment costs for cancers detected at an earlier stage, appear much later in the model, particularly as the cohort ages and cancer incidence rises. Consequently, the model is very sensitive to discounting assumptions for cost and QALYs.

The ICER calculated in this study is higher than previously published cost-effectiveness estimates from the UK, but lower than those from the US [20–22, 24]. In the UK study by Norman et al., women were screened for only 10 years, beginning at age 30 or 40 years, giving ICERS of approximately CAD$17,600 and $30,600 per QALY [24]. By contrast, our model includes MRI screening from age 25 to 65 years. In the US studies, the cost of MRI was much higher than in this study, around USD$1000 for a bilateral screen, which is a potential reason why the reported ICERs are also higher. Moore et al. found in their sensitivity analysis that reducing the cost of MRI to below USD$315 resulted in an ICER of under USD$50,000/QALY, down from the base-case ICER of nearly USD$180,000/QALY, which is more consistent with the findings of this study [22]. Both Moore’s model and this study highlight the fact that MRI screening for breast cancer may be cost effective, when the cost of MRI scans is low.

A limitation of this model is that it represents an idealized screening program, with all women entering at age 25 and participating until age 65 or until they develop cancer. The MRI screening program operated by the BCCA has a dynamic population. Women join the program at various ages when they are deemed to be eligible, and leave after undergoing prophylactic surgery, after developing cancer, or for other reasons. The timing of screening also varies: women who must travel to Vancouver for screening often have both MRI and mammography done concurrently, and the interval between MRI screens may exceed 12 months. Consequently, the cost-effectiveness of the screening program, if it were to be measured using real-world, comparative effectiveness program data, may be different. Although our goal was to use as much local data as possible, the challenge of acquiring comparative effectiveness data to inform the model was a further limitation of this study. We had insufficient sample size and follow-up to fully evaluate the effectiveness of the BCCA’s MRI screening program. We instead relied on the literature for screening effectiveness data. A further limitation of the model is that we were unable to include the risk of overdiagnosis from additional screening with MRI. Estimates of overdiagnosis attributable to mammography screening vary widely, from under 10% to as high as 50% [43–46]; however, overdiagnosis from MRI screening has not been assessed, nor has the rate of overdiagnosis in the BRCA1/2 population.

The model that we constructed to assess the cost-effectiveness of MRI screening lays the foundation to potentially address other questions related to breast cancer screening. For example, as more data become available the model could be adapted to find the optimal start time and duration of MRI screening from a cost-effectiveness perspective, or to investigate the relationship between lifetime breast cancer risk and cost-effectiveness of MRI screening, exploring the feasibility of expanding MRI screening to other high-risk groups.

Conclusions

Annual mammography plus MRI screening of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers at the BCCA was found to be potentially cost-effective, with an ICER of $50,900/QALY when compared to annual mammography alone, although the cost-effectiveness is finely balanced. The benefits of early detection of breast cancer with MRI in this population may outweigh the added cost of screening and the higher risk of false positives; however, the cost-effectiveness of MRI screening is highly dependent on the cost of MRI scans and there remains some statistical uncertainty around the results.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

British Columbia

- BCCA:

-

BC Cancer agency

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-year.

References

Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, Loman N, Olsson H, Johannsson O, Borg A, et al: Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003, 72: 1117-1130. 10.1086/375033.

Chen SN, Parmigiani G: Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 1329-1333. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066.

BC Cancer Agency: Hereditary Cancer Program Referrals. http://www.screeningbc.ca/Hereditary/ForHealthProfessionals/ReferralProcess.htm,

Eisen A, Lubinski J, Klijn J, Moller P, Lynch HT, Offit K, Weber B, Rebbeck T, Neuhausen SL, Ghadirian P, et al: Breast cancer risk following bilateral oophorectorny in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: An international case–control study. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 7491-7496. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7138.

Kurian AW, Sigal BM, Plevritis SK: Survival Analysis of Cancer Risk Reduction Strategies for BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 28: 222-231.

Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WLJ, Henzen-Logmans SC, Seynaeve C, Menke-Pluymers MBE, Bartels CCM, Verhoog LC, van den Ouweland AMW, Niermeijer MF, et al: Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Eng J Med. 2001, 345: 159-164. 10.1056/NEJM200107193450301.

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, van't Veer L, Garber JE, Evans GR, Narod SA, Isaacs C, Matloff E, et al: Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: The PROSE study group. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 1055-1062. 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.188.

Howard AF, Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Rodney P: Preserving the Self: The Process of Decision Making About Hereditary Breast Cancer and Ovarian Cancer Risk Reduction. Qual Health Res. 2011, 21: 502-519. 10.1177/1049732310387798.

Saslow D: American cancer society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007, 57: 75-89. 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75.

Kriege M, Brekelmans CTM, Boetes C, Besnard PE, Zonderland HM, Obdeijn IM, Manoliu RA, Kok T, Peterse H, Tilanus-Linthorst MMA, et al: Efficacy of MRI and mammography for breast-cancer screening in women with a familial or genetic predisposition. N Eng J Med. 2004, 351: 427-437. 10.1056/NEJMoa031759.

Warner E, Plewes DB, Hill KA, Causer PA, Zubovits JT, Jong RA, Cutrara MR, DeBoer G, Yaffe MJ, Messner SJ, et al: Surveillance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers With Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Ultrasound, Mammography, and Clinical Breast Examination. JAMA. 2004, 292: 1317-1325. 10.1001/jama.292.11.1317.

Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Leutner CC, Morakkabati-Spitz N, Wardelmann E, Fimmers R, Kuhn W, Schild HH: Mammography, Breast Ultrasound, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Surveillance of Women at High Familial Risk for Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 8469-8476. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4960.

Leach MO, Boggis CRM, Dixon AK, Easton DF, Eeles RA, Evans DGR, Gilbert FF, Griebsch I, Hoff RJC, Kessar P, et al: Screening with magnetic resonance imaging and mammography of a UK population at high familial risk of breast cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (MARIBS). Lancet. 2005, 365: 1769-1778.

Kriege M, Brekelmans CT, Boetes C, Muller SH, Zonderland HM, Obdeijn IM, Manoliu RA, Kok T, Rutgers EJ, de Koning HJ, Klijn JG: Differences between first and subsequent rounds of the MRISC breast cancer screening program for women with a familial or genetic predisposition. Cancer. 2006, 106: 2318-2326. 10.1002/cncr.21863.

Lord SJ, Lei W, Craft P, Cawson JN, Morris I, Walleser S, Griffiths A, Parker S, Houssami N: A systematic review of the effectiveness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as an addition to mammography and ultrasound in screening young women at high risk of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43: 1905-1917. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.007.

Warner E, Messersmith H, Causer P, Eisen A, Shumak R, Plewes D: Systematic review: Using magnetic resonance imaging to screen women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 671-679. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00007.

Sardanelli F, Podo F, Santoro F, Manoukian S, Bergonzi S, Trecate G, Vergnaghi D, Federico M, Cortesi L, Corcione S, et al: Multicenter surveillance of women at high genetic breast cancer risk using mammography, ultrasonography, and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (the high breast cancer risk italian 1 study): final results. Invest Radiol. 2011, 46: 94-105. 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181f3fcdf.

Le-Petross HT, Whitman GJ, Atchley DP, Yuan Y, Gutierrez-Barrera A, Hortobagyi GN, Litton JK, Arun BK: Effectiveness of alternating mammography and magnetic resonance imaging for screening women with deleterious BRCA mutations at high risk of breast cancer. Cancer. 2011, 117: 3900-3907. 10.1002/cncr.25971.

Gilbert FJ, Cordiner CM, Affleck IR, Hood DB, Mathieson D, Walker LG: Breast screening: the psychological sequelae of false-positive recall in women with and without a family history of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1998, 34: 2010-2014. 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00294-9.

Plevritis SK, Kurian AW, Sigal BM, Daniel BL, Ikeda DM, Stockdale FE, Garber AM: Cost-effectiveness of screening BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with breast magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2006, 295: 2374-2384. 10.1001/jama.295.20.2374.

Lee JM, McMahon PM, Kong CY, Kopans DB, Ryan PD, Ozanne EM, Halpern EF, Gazelle GS: Cost-effectiveness of Breast MR Imaging and Screen-Film Mammography for Screening BRCA1 Gene Mutation Carriers. Radiology. 2010, 254: 793-800. 10.1148/radiol.09091086.

Moore S, Shenoy P, Fanucchi L, Tumeh J, Flowers C: Cost-effectiveness of MRI compared to mammography for breast cancer screening in a high risk population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009, 9: 9-10.1186/1472-6963-9-9.

Griebsch I, Brown J, Boggis C, Dixon A, Dixon M, Easton D, Eeles R, Evans DG, Gilbert FJ, Hawnaur J, et al: Cost-effectiveness of screening with contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging vs X-ray mammography of women at a high familial risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006, 95: 801-810. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603356.

Norman RPA, Evans DG, Easton DF, Young KC: The cost-utility of magnetic resonance imaging for breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers aged 30–49. Eur J Health Econ. 2007, 8: 137-144. 10.1007/s10198-007-0042-9.

Chia SK, Speers CH, D'Yachkova Y, Kang A, Malfair-Taylor S, Barnett J, Coldman A, Gelmon KA, O'Reilly SE, Olivotto IA: The impact of new chemotherapeutic and agents on survival in a population-based of women with metastatic breast cancer hormone cohort. Cancer. 2007, 110: 973-979. 10.1002/cncr.22867.

Kerlikowske K, Carney PA, Geller B, Mandelson MT, Taplin SH, Malvin K, Ernster V, Urban N, Cutter G, Rosenberg R, Ballard-Barbash R: Performance of screening mammography among women with and without a first-degree relative with breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 133: 855-863. 10.7326/0003-4819-133-11-200012050-00009.

Hagen AI, Kvistad KA, Maehle L, Holmen MM, Aase H, Styr B, Vabo A, Apold J, Skaane P, Moller P: Sensitivity of MRI versus conventional screening in the diagnosis of BRCA-associated breast cancer in a national prospective series. Breast. 2007, 16: 367-374. 10.1016/j.breast.2007.01.006.

Lee JM, Kopans DB, McMahon PM, Halpern EF, Ryan PD, Weinstein MC, Gazelle GS: Breast cancer screening in BRCA1 mutation carriers: Effectiveness of MR imaging - Markov Monte Carlo decision analysis. Radiology. 2008, 246: 763-771. 10.1148/radiol.2463070224.

Briggs A, Schulpher M, Claxton K: Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. 2006, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Liebens FP, Carly B, Pastijn A, Rozenberg S: Management of BRCA1/2 associated breast cancer: A systematic qualitative review of the state of knowledge in 2006. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43: 238-257. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.07.019.

Mai PL, Chatterjee N, Hartge P, Tucker M, Brody L, Struewing JP, Wacholder S: Potential Excess Mortality in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers beyond Breast, Ovarian, Prostate, and Pancreatic Cancers, and Melanoma. PLoS One. 2009, 4: e4812-10.1371/journal.pone.0004812.

BC Medical Services Commission Payment Schedule. 2008, http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/msp/infoprac/physbilling/payschedule/index.html,

Screening Mammography Program: 2007/2008 Annual Report. Book 2007/2008 Annual Report. 2008, City: BC Cancer Agency

Costing Analysis (CAT) Tool. http://www.occp.com/mainPage.htm,

Health Employers Association of BC Collective Agreements. http://www.heabc.bc.ca/Page20.aspx,

Najafzadeh M, Marra CA, Sadatsafavi M, Aaron SD, Sullivan SD, Vandemheen KL, Jones PW, Fitzgerald JM: Cost effectiveness of therapy with combinations of long acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids for treatment of COPD. Thorax. 2008, 63: 962-967. 10.1136/thx.2007.089557.

Neutel C, Gao R, Gaudette L, Johansen H: Shorter hospital stays for breast cancer. Health Rep. 2004, 16: 19-31.

Schleinitz MD, DePalo D, Blume J, Stein M: Can differences in breast cancer utilities explain disparities in breast cancer care?. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 1253-1260. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00609.x.

Bonomi AE, Boudreau DM, Fishman PA, Ludman E, Mohelnitzky A, Cannon EA, Seger D: Quality of life valuations of mammography screening. Qual Life Res. 2008, 17: 801-814. 10.1007/s11136-008-9353-2.

Earle CC, Chapman RH, Baker CS, Bell CM, Stone PW, Sandberg EA, Neumann PJ: Systematic overview of cost-utility assessments in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000, 18: 3302-3317.

Longson C, Longworth L, Turner K, Dillon A, Barnett D, Culyer T, Littlejohns P, Stevens A: Book Guide to the methods of technology appraisal, Issued: June 2008.2008, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: City,

Byrd LM, Shenton A, Maher ER, Woodward E, Belk R, Lim C, Lalloo F, Howell A, Jayson GC, Evans GD: Better Life Expectancy in Women with BRCA2 Compared with BRCA1 Mutations Is Attributable to Lower Frequency and Later Onset of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Epi Bio Prev. 2008, 17: 1535-1542. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2792.

Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC: Overdiagnosis in publicly organised mammography screening programmes: systematic review of incidence trends. BMJ. 2009, 339: b2587-10.1136/bmj.b2587.

Kalager M, Adami HO, Bretthauer M, Tamimi RM: Overdiagnosis of Invasive Breast Cancer Due to Mammography Screening: Results From the Norwegian Screening Program. Ann Intern Med. 2012, 156: 491-499. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00005.

Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening: The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet. 2012, 380: 1778-1786.

Moss S: Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer: Overdiagnosis in randomised controlled trials of breast cancer screening. Breast Cancer Res. 2005, 7: 230-234. 10.1186/bcr1314.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/13/339/prepub

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, grant no. PHE-81956.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the model design and validation, interpretation of results, and to critical review of this manuscript. RP was responsible for model construction, data analysis and composing the manuscript. JS, CW, CKS, and AC provided data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pataky, R., Armstrong, L., Chia, S. et al. Cost-effectiveness of MRI for breast cancer screening in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. BMC Cancer 13, 339 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-339

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-339