Abstract

Background

The identification of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood is a useful approach to estimate prognosis, monitor disease progression, and measure treatment effects in various malignancies. However, clinical relevance of CTCs is controversial. We attempted to detect viable CTCs in the peripheral blood of gastric cancer patients using a telomerase-specific viral agent.

Methods

We took a 7.5-ml blood sample from 65 treatment-negative gastric cancer patients before surgery and 10 healthy volunteers. We detected viable CTCs in the blood samples after incubating them with a telomerase-specific, replication-selective, oncolytic adenoviral agent carrying the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (OBP-401). GFP-positive CTCs were defined as having a diameter of at least 7.735 μm; this threshold was determined by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. GFP-positive cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope.

Results

There was a significant difference in overall survival among the patients with 0–4 and those with ≥5 GFP-positive CTCs in the stage I–IV disease group and stage II–IV advanced disease group. The number of GFP-positive CTCs was not related to cancer stage. Among the pathological findings, the number of GFP-positive CTCs was only significantly related to venous invasion, although there were trends towards more GFP-positive CTCs with disease progression (tumour depth, lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, lymphatic invasion, and histological type).

Conclusions

There was a significant relationship between the number of GFP-positive CTCs and overall survival in the patients with gastric cancer. The detection of CTCs using OBP-401 may be useful for prognostic evaluation.

Trial registration

University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan, UMIN000002018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Distant metastasis of a solid tumour is a strong prognostic factor [1–3]. The existence of circulating tumour cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood suggests that a patient is in a systemic disease phase [4]. The identification of CTCs in peripheral blood is a useful approach to estimate prognosis, monitor disease progression, and measure treatment effects in breast, prostate, skin, colon and gastrointestinal malignancies. Therefore, various methods have been developed to detect CTCs, and are occasionally used in combination. Common techniques for the enrichment and detection of CTCs are density gradient separation [5], direct enrichment by filtration [6, 7], immunomagnetic separation [8], flow cytometry [9], real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [10, 11], and microchip technology [12].

Cell enrichment by density gradient separation is performed using commercial kits such as OncoQuick® (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) [13] and Lymphoprep® (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) [14]. Density gradient separation is based on the theory that different types of cells can be separated according to their density. Therefore, it is difficult to extract all CTCs because of cell migration. RT-PCR is one of the most common methods of tumour cell detection because of its high sensitivity and specificity, assuming adequate primer and probe design. However, false-positive results may occur because of its technical delicacy and high sensitivity [15, 16].

Immunomagnetic cell enrichment, such as that performed by the CellSearch System® (Veridex, LLC, Raritan, NJ, USA) [17], is currently the most commonly used technique to enrich and detect CTCs [18–21]. The advantage of immunomagnetic cell separation is that CTCs can be visualised with a fluorescent microscope. Cells detected with antibodies against epithelial markers (epithelial cell adhesion molecules; EpCAMs) are determined to be CTCs. Therefore, this technique can provide false-positive results based on normal epithelial marker expression by non-tumour cells, and false-negative results can arise based on the lack of selective marker expression on tumour cells. As a result of the limitations associated with the above approaches, a new technique is needed to detect viable CTCs precisely.

Telomerase plays important roles in carcinogenesis, cancer invasion, and metastasis [22–24]. We have developed a technique to exploit high telomerase activity in cells. This technique uses a telomerase-specific, replication-selective modified viral agent (OBP-401; TelomeScan®, Oncolys BioPharma, Tokyo, Japan) in which the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene promoter is inserted into the E1 region, and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene is placed under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter in the E3 region as a marker of viral replication [25]. It has been reported that OBP-401 can be used to detect viable CTCs among normal blood cells [26, 27].

Here, we applied the assay to detect viable CTCs with the potential for metastasis in gastric cancer patients. We detected GFP-positive CTCs. In contrast, it is possible that non-cancer cells emit GFP fluorescence after OBP-401 infection [28]. Therefore, we selected cells larger than a threshold determined by comparison between healthy volunteers and patients, because CTCs are larger than normal blood cells [7, 29, 30]. We studied the association of GFP-positive CTC number with survival and pathological indices of disease progression.

Methods

Patients and healthy volunteers

The patients included in this preliminary study were those undergoing planned surgical treatment; patients who were suitable for endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection were excluded. The inclusion criteria were: (i) histologically proven adenocarcinoma of the stomach by endoscopic biopsy; (ii) clinical solitary tumour; (iii) no prior endoscopic resection, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy; (iv) age 20–80 years; (v) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [31] 0 or 1; (vi) sufficient organ function; and (vii) written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: (i) synchronous or metachronous malignancy; (ii) pregnant or breastfeeding women; (iii) active or chronic viral hepatitis; (iv) active bacterial or fungal infection; (v) diabetes mellitus; (vi) systemic administration of corticosteroids; and (vii) unstable hypertension. The disease stage in the patients was pathologically characterised using the seventh edition of the TNM classification of the International Union Against Cancer [32]. The depth of the tumour in three patients without gastrectomy and the regional lymph node status of five patients without sufficient lymphadenectomy were diagnosed surgically.

All the patients attended our hospital regularly after surgery, and were checked every 3 months. The patients also underwent endoscopy and computed tomography at least once a year, according to their disease stage and course.

We also recruited healthy volunteers to act as controls. All healthy volunteers were employees of Sysmex Corporation and included seven men (mean age 31.4 years, range 24–39 years) and three women (mean age 33.7 years, range 26–48 years). All volunteers underwent medical check-ups upon employment and annually; check-ups included medical interviews, auscultation, chest radiographs, and blood and urine analyses. Furthermore, we performed individual interviews before sample collection; any volunteer who was currently receiving medical treatment, pregnant or breastfeeding, or who had donated blood within the past month was excluded.

Virus

OBP-401, a telomerase-specific, replication-selective adenoviral agent in which the TERT promoter element drives the expression of the EIA and EIB genes, and into which the GFP gene is integrated, was used in this study. Sensitivity and specificity of the assay using OBP-401 have been studied previously by Kim et al. [27]. The test was repeated five times test in the sample including 1 MDA-MB-468 (breast carcinoma) cells and 7.5 ml blood, and the numbers of GFP-positive cells were 1, 1, 1, 2 and 3; in the sample including 20 MDA-MB-468 (breast carcinoma) cells, the numbers of GFP-positive cells were 15, 17, 19, 22 and 24. Viral samples were stored at −80°C.

Cell lines and culture

The A549 (lung carcinoma), HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), HEC-1 (endometrial adenocarcinoma), KATO-III (gastric carcinoma), and SBC-3 (small cell lung carcinoma) cell lines were obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). The LNCaP (prostate adenocarcinoma) and OVCAR-3 (ovarian carcinoma) cell lines were obtained from the Riken Cell Bank (Tokyo, Japan). The cells were cultured according to the vendor’s specifications. MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured as previously described [27].

Sample preparation and cell counting

A 7.5-ml peripheral vein blood sample was obtained from each patient before surgery and from each volunteer. The samples were drawn into tubes containing citric acid, phosphoric acid, and dextrose, and stored at 4°C. The assay was started within 48 h.

The samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 540 g and the plasma phase was removed. The cells were then washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and twice with Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium. The samples were infected with 4 × 108 plaque-forming units (PFU) of OBP-401 viruses by incubation in the medium for 24 hours at 37°C.

After dead cell staining by the red-fluorescent reactive dye L23102 (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA), OBP-401 viruses were inactivated and cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature.

The samples were treated with a surface-active agent (Emalgen 2025 G; Kao Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) for 10 min at 40°C to degrade red blood cells. Finally, 7.5 ml blood was used to create two glass slide samples for microscopic analysis. All GFP-positive cells on the two slides were counted, using a computer-controlled fluorescent microscope (IX71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an examiner blinded to the sample details. The total assay time was 27.5 h (Figure 1).

Protocol and procedure of the “GFP-CTC Assay”. Each 7.5-ml peripheral vein blood sample was obtained from patients before surgery and from volunteers. The samples were drawn into tubes containing citric acid, phosphoric acid and dextrose. The samples were centrifuged and the plasma phase was removed. After cell washing using PBS and Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium, the samples were infected with 4 × 108 PFU of OBP-401 virus. OBP-401 virus was inactivated and cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The samples were treated with a surface-active agent to degrade red and white blood cells. Two glass slide samples from 7.5 ml blood were prepared for microscopic analysis. All GFP-positive cells on the two slides were counted using a computer-controlled fluorescent microscope.

Determination of GFP fluorescence intensity threshold

The threshold for GFP fluorescence intensity was determined as follows. Approximately 30,000 cultured cells were spiked into 7.5-ml blood samples from healthy volunteers, which were spiked with various cancer cell lines: A549, HepG2, HEC-1, KATO-III, SBC-3, LNCaP, MDA-MB-MB468 and OVCAR-3. Blood samples were subjected to CTC detection assay, and then detectable cells were counted by fluorescence microscopy. More than 100 cells were analysed in each sample. We determined 2.85 × 107 mean equivalent fluorochrome to be the threshold for GFP signal intensity from the minimal GFP intensity level observed in the blood samples spiked with the cell lines (Figure 2). Data are reported as the numbers of GFP-positive CTCs per 7.5-ml peripheral blood sample.

Immunostaining

Phycoerythrin-labelled anti-human CD45 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was diluted 1:5 and Pacific Blue-labelled anti-human CD326 (EpCAM) antibody (BioLegend) was diluted 1:10 in PBS containing 2% foetal bovine serum. Cells were incubated with diluted antibodies for 30 min at 25°C. After washing with PBS containing 2% foetal bovine serum, cells were mounted on glass slides and analysed using a fluorescence microscope (IX71; Olympus).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Statistical Discovery 9.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To determine the cell diameter threshold, the detected GFP-positive CTCs were analysed using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve between the samples from gastric cancer patients and those from volunteers. For multiple group comparisons, homogeneity of variance was assessed by the Levene test. For parametric comparisons we used analysis of variance, and for non-parametric comparisons we used the Wilcoxon and the Kruskal–Wallis tests. We used Fisher’s exact and χ 2 tests with a 2 × 2 and a 4 × 2 table, respectively, to compare the clinicopathological characters in the patient group. Kaplan–Meier curves of estimated disease-free survival and overall survival were generated, and comparisons among the groups were performed using a two-sided log-rank test. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Showa University, Northern Yokohama Hospital. We explained the study protocol to the patients and volunteers before they gave written informed consent. This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan, number 000002018.

Results

Participant characteristics

Sixty-five patients with gastric adenocarcinoma (46 men and 19 women; mean age 58.8 years, range 33–76 years) who underwent surgery at the Digestive Disease Center of the Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital between September 2009 and May 2011 were included in this study. Twenty-nine had distal gastrectomy, 32 had total gastrectomy, and four had exploratory laparotomy. The patients’ characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Twenty-eight of the 65 patients received chemotherapy after surgery. The control group comprised 10 healthy volunteers.

GFP-positive CTCs in peripheral blood

Using a fluorescence microscope, cells with fluorescent emissions ≥2.85 × 107 mean equivalent fluorochrome were counted as GFP-positive cells.

Various sizes of GFP-positive cells were observed in each sample; therefore, it was difficult to identify one representative cell among the GFP-positive cells for comparison between patients and healthy volunteers. Therefore, to avoid using an arbitrary value, we decided to use the optimum threshold derived from the ROC analysis based on the cell size, that is, 7.735 μm, as the threshold to define GFP-positive CTCs (Figure 3).

Comparison of cell diameter between patients and volunteers. To determine the threshold, we compared the diameters of cells from gastric cancer patients and controls by ROC analysis. There was a significant difference between the gastric cancer patients and the controls (p < 0.001; area under the curve = 0.57; 95% confidence interval = 0.54–0.60).

By immunohistochemical staining using anti-EpCAM and anti-CD45 antibodies, we confirmed that GFP-positive CTCs were EpCAM-positive and CD45-negative (Figure 4).

Examples of microscopic images. Representative images from two gastric cancer samples of GFP-positive CTCs and immunocytochemical analysis of anti-EpCAM- and anti-CD45-positive cells. Cells were counted using a computer-controlled fluorescence microscope by an examiner blinded to the sample status. Scale bar, 10 μm.

The numbers of GFP-positive CTCs in the peripheral blood samples are shown in Figure 5. There was no significant difference among the detection rates of GFP-positive CTCs in the samples representing each cancer stage.

Number of GFP-positive cells. The dots are the numbers of GFP-positive CTCs in the patient samples. The bottom and top of the box represent the lower and upper quartiles, and the band across the box shows the median. The lower and upper bars at the ends of the whiskers show the lowest data point within 1.5 interquartile ranges of the lower quartile, and the highest data point within 1.5 interquartile ranges of the upper quartile, respectively. The green bars indicate mean value.

Association of GFP-positive CTCs with survival

The mean number of GFP-positive CTCs in the samples from 10 healthy volunteers was 4.8. We divided the patients into two groups based on the numbers of GFP-positive CTCs: 0–4 and ≥5. The clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups are summarised in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups except that there was only one category of lymphatic metastasis.

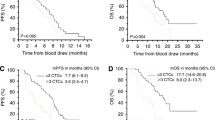

Figure 6a shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in the two groups: the patients with 0–4 CTCs and those with ≥5. There was a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.0021). Furthermore, in the advanced gastric cancer patients with stage II–IV disease, there was a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.0126) (Figure 6b).

Association of GFP-positive CTCs with pathological indices

There was no significant relationship between the number of GFP-positive CTCs and cancer stage (p = 0.2313) (Figure 5). Although no statistical significance was observed, the number of GFP-positive CTCs tended to increase with the progression of the primary tumour (p = 0.1521) (Figure 7a). The number of CTCs in the samples from the node-positive patients was greater than that in the node-negative patients (p = 0.1752) (Figure 7b). Compared with the patients without distant metastases, those with distant metastases had similar numbers of GFP-positive CTCs (p = 0.5655) (Figure 7c). There was not a significant difference between the differentiated and undifferentiated type (p = 0.8387) (Figure 7d). The numbers of CTCs were similar in the samples from patients with and without lymphatic invasion (p = 0.2054) (Figure 7e). For venous invasion, the number of CTCs in the samples from the patients with invasion was significantly higher than that in patients without invasion (p = 0.0351) (Figure 7f).

Relationship between number of GFP-positive CTCs in a 7.5-ml blood sample from gastric cancer patients and pathological findings in the patients. The dots are the numbers of GFP-positive CTCs in the patient samples. The bottom and top of the box represent the lower and upper quartiles, and the band across the box shows the median. The lower and upper bars at the ends of the whiskers show the lowest data point within 1.5 interquartile ranges of the lower quartile, and the highest data point within 1.5 interquartile ranges of the upper quartile, respectively. a, Tumour invasion depth (T1–T4 indicate increasing depth). b, Lymphatic metastasis (N0 = negative, N1–3 = positive). c, Distant metastasis (M0 = negative, M1 = positive). d, Histological type (differentiated type and undifferentiated type). e, Lymphatic invasion (L0 = negative, L1 = positive). f, Venous invasion (V0 = negative, V1 = positive), *p < 0.05. Although only venous invasion displayed a statistically significant difference, there were some trends towards an increase in CTC number with increasing disease progression.

Discussion

This paper reports the correlation between CTCs and gastric cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The usefulness of the detection of CTCs in the diagnosis, estimation of prognosis, and evaluation of treatment effects has already been reported for breast [27, 33], prostate [34], lung [35] and digestive tract [11, 36, 37] cancers. This study indicates that it is also useful for gastric cancer.

One major outcome of our study was a significant relationship between the number of CTCs and prognosis. Although we used a short follow-up period, the prognosis of patients who had ≥5 CTCs in their 7.5-ml peripheral blood samples was poor. Patients with early stage disease generally have a lower recurrence rate [38], and those with stage I disease actually had no recurrence in our study. We also calculated survival rate in advanced gastric cancer patients with stage II–IV disease, and showed that these patients had a similar survival pattern to those with stage I–IV disease. These results suggest that preoperative chemotherapy or comprehensive treatment is appropriate for advanced disease patients who have many CTCs in pretreatment samples because of their poor prognosis.

Among our pathological findings, only venous invasion had a significant relationship with the number of CTCs. This suggests agreement between traditional pathology and modern molecular technology. We believe that the lack of a significant difference between the number of CTCs detected by our assay and the other pathological indices can be explained by methodological issues such as the small sample size. Our technique worked well as a prognostic evaluation tool — to provide information about the need for postoperative adjuvant therapy — and it may provide a useful auxiliary tool to pathology-based classification.

It is not clear whether all detected CTCs have metastatic potential. Viable CTCs were detected in the samples from early-stage cancer patients in the present study, but almost all stage I group patients survived without recurrence [38]. We intend to confirm whether resistant cancer cells, like cancer stem cells, were present in the detected GFP-positive cells. Also, we will analyse the functions of viable CTCs individually after cell sorting, and identify CTCs with metastatic potential using additional tools such as DNA ploidy analysis [39, 40]. Furthermore, gene expression profiling among viable CTCs, dead cells, primary tumours, and metastatic tumours will reveal important information related to the mechanisms of cancer metastasis.

Our results must be interpreted with some caution, considering the limitations of this study. First, the number of CTCs varied widely between individuals, including patients and healthy volunteers. Moreover, it was not influenced by tumour stage or the presence of clinically detectable metastases. Similarly, there was no association between the presence of metastases (lymph node or distant) or invasion and the number of CTCs, which brings into question the use of CTCs to predict metastatic potential. However, it is possible that the relatively small sample size limited the potential to detect real differences between these groups of patients. Finally, it must be acknowledged that our results are only applicable to preoperative, treatment-naïve gastric cancer and should not be generalised to other types of cancer.

Clearly, more studies in a larger population of patients, and with different cancer types, are needed to clarify the clinical applicability of CTC detection. We are now preparing a study to investigate the effects of gastric cancer treatment on the number of CTCs, which should help to establish their relationship with future disease progression and whether CTC count can help guidetherapy choice.

Conclusions

There was a significant difference in survival between patients with 0–4 CTCs and those with ≥5. However, it is unclear whether all CTCs have true metastatic potential, and further studies are needed.

References

Kowalski LP: Lymph node metastasis as a prognostic factor in laryngeal cancer. Rev Paul Med. 1993, 111 (4): 42-45.

Nakane Y, Okamura S, Masuya Y, Okumura S, Akehira K, Hioki K: Incidence and prognosis of para-aortic lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998, 45 (23): 1901-1906.

Arai Y, Kanamaru H, Yoshimura K, Okubo K, Kamoto T, Yoshida O: Incidence of lymph node metastasis and its impact on long-term prognosis in clinically localized prostate cancer. International journal of urology: official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 1998, 5 (5): 459-465. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00388.x.

Liotta LA, Kleinerman J, Saidel GM: Quantitative relationships of intravascular tumor cells, tumor vessels, and pulmonary metastases following tumor implantation. Cancer Res. 1974, 34 (5): 997-1004.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000, 100 (1): 57-70. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9.

Vona G, Estepa L, Beroud C, Damotte D, Capron F, Nalpas B, Mineur A, Franco D, Lacour B, Pol S, et al: Impact of cytomorphological detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with liver cancer. Hepatology. 2004, 39 (3): 792-797. 10.1002/hep.20091.

Vona G, Sabile A, Louha M, Sitruk V, Romana S, Schutze K, Capron F, Franco D, Pazzagli M, Vekemans M, et al: Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells: a new method for the immunomorphological and molecular characterization of circulatingtumor cells. Am J Pathol. 2000, 156 (1): 57-63. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64706-2.

Talasaz AH, Powell AA, Huber DE, Berbee JG, Roh KH, Yu W, Xiao W, Davis MM, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, et al: Isolating highly enriched populations of circulating epithelial cells and other rare cells from blood using a magnetic sweeper device. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106 (10): 3970-3975. 10.1073/pnas.0813188106.

He W, Wang H, Hartmann LC, Cheng JX, Low PS: In vivo quantitation of rare circulating tumor cells by multiphoton intravital flow cytometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104 (28): 11760-11765. 10.1073/pnas.0703875104.

Ito H, Kanda T, Nishimaki T, Sato H, Nakagawa S, Hatakeyama K: Detection and quantification of circulating tumor cells in patients with esophageal cancer by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Journal of experimental clinical cancer research: CR. 2004, 23 (3): 455-464.

Honma H, Kanda T, Ito H, Wakai T, Nakagawa S, Ohashi M, Koyama Y, Valera VA, Akazawa K, Hatakeyama K: Squamous cell carcinoma-antigen messenger RNA level in peripheral blood predicts recurrence after resection in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2006, 139 (5): 678-685. 10.1016/j.surg.2005.09.022.

Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, et al: Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007, 450 (7173): 1235-1239. 10.1038/nature06385.

Gertler R, Rosenberg R, Fuehrer K, Dahm M, Nekarda H, Siewert JR: Detection of circulating tumor cells in blood using an optimized density gradient centrifugation. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003, 162: 149-155. 10.1007/978-3-642-59349-9_13.

Marth C, Kisic J, Kaern J, Trope C, Fodstad O: Circulating tumor cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with ovarian carcinoma do not predict prognosis. Cancer. 2002, 94 (3): 707-712. 10.1002/cncr.10250.

Silva JM, Rodriguez R, Garcia JM, Munoz C, Silva J, Dominguez G, Provencio M, Espana P, Bonilla F: Detection of epithelial tumour RNA in the plasma of colon cancer patients is associated with advanced stages and circulating tumour cells. Gut. 2002, 50 (4): 530-534. 10.1136/gut.50.4.530.

Hara N, Kasahara T, Kawasaki T, Bilim V, Obara K, Takahashi K, Tomita Y: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detection of prostate-specific antigen, prostate-specific membrane antigen, and prostate stem cell antigen in one milliliter of peripheral blood: value for the staging of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002, 8 (6): 1794-1799.

Cohen SJ, Punt CJ, Iannotti N, Saidman BH, Sabbath KD, Gabrail NY, Picus J, Morse M, Mitchell E, Miller MC, et al: Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26 (19): 3213-3221. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8923.

Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Muller V, Rau T, Schindlbeck C, Rack B, Janni W, Coith C, Beck K, Janicke F, et al: Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the Cell Search system. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13 (3): 920-928. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1695.

Davis JW, Nakanishi H, Kumar VS, Bhadkamkar VA, McCormack R, Fritsche HA, Handy B, Gornet T, Babaian RJ: Circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood samples from patients with increased serum prostate specific antigen: initial results in early prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008, 179 (6): 2187-2191. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.102. discussion 2191

Pierga JY, Bidard FC, Mathiot C, Brain E, Delaloge S, Giachetti S, de Cremoux P, Salmon R, Vincent-Salomon A, Marty M: Circulating tumor cell detection predicts early metastatic relapse after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in large operable and locally advanced breast cancer in a phase II randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14 (21): 7004-7010. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0030.

Hou JM, Greystoke A, Lancashire L, Cummings J, Ward T, Board R, Amir E, Hughes S, Krebs M, Hughes A, et al: Evaluation of circulating tumor cells and serological cell death biomarkers in small cell lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Am J Pathol. 2009, 175 (2): 808-816. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090078.

Blackburn EH: Telomere states and cell fates. Nature. 2000, 408 (6808): 53-56. 10.1038/35040500.

Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW: Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994, 266 (5193): 2011-2015. 10.1126/science.7605428.

Bilsland AE, Merron A, Vassaux G, Keith WN: Modulation of telomerase promoter tumor selectivity in the context of oncolytic adenoviruses. Cancer Res. 2007, 67 (3): 1299-1307. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3000.

Fujiwara T, Kagawa S, Kishimoto H, Endo Y, Hioki M, Ikeda Y, Sakai R, Urata Y, Tanaka N: Enhanced antitumor efficacy of telomerase-selective oncolytic adenoviral agent OBP-401 with docetaxel: preclinical evaluation of chemovirotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2006, 119 (2): 432-440. 10.1002/ijc.21846.

Kojima T, Hashimoto Y, Watanabe Y, Kagawa S, Uno F, Kuroda S, Tazawa H, Kyo S, Mizuguchi H, Urata Y, et al: A simple biological imaging system for detecting viable human circulating tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119 (10): 3172-3181. 10.1172/JCI38609.

Kim SJ, Masago A, Tamaki Y, Akazawa K, Tsukamoto F, Sato J, Ozawa T, Tsujino Y, Noguchi S: A novel approach using telomerase-specific replication-selective adenovirus for detection of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011, 128 (3): 765-773. 10.1007/s10549-011-1603-2.

Kishimoto H, Kojima T, Watanabe Y, Kagawa S, Fujiwara T, Uno F, Teraishi F, Kyo S, Mizuguchi H, Hashimoto Y, et al: In vivo imaging of lymph node metastasis with telomerase-specific replication-selective adenovirus. Nat Med. 2006, 12 (10): 1213-1219. 10.1038/nm1404.

Lin HK, Zheng S, Williams AJ, Balic M, Groshen S, Scher HI, Fleisher M, Stadler W, Datar RH, Tai YC, et al: Portable filter-based microdevice for detection and characterization of circulating tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16 (20): 5011-5018. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1105.

Zheng S, Lin HK, Lu B, Williams A, Datar R, Cote RJ, Tai YC: 3D microfilter device for viable circulating tumor cell (CTC) enrichment from blood. Biomedical microdevices. 2011, 13 (1): 203-213. 10.1007/s10544-010-9485-3.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP: Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American journal of clinical oncology. 1982, 5 (6): 649-655. 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014.

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C: TNM classification of malignant tumours. 2010, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 7

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LW, et al: Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2004, 351 (8): 781-791. 10.1056/NEJMoa040766.

Moreno JG, Miller MC, Gross S, Allard WJ, Gomella LG, Terstappen LW: Circulating tumor cells predict survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2005, 64 (4): 713-718.

Krebs MG, Sloane R, Priest L, Lancashire L, Hou JM, Greystoke A, Ward TH, Ferraldeschi R, Hughes A, Clack G, et al: Evaluation and prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (12): 1556-1563. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7045.

Katsumata K, Sumi T, Mori Y, Hisada M, Tsuchida A, Aoki T: Detection and evaluation of epithelial cells in the blood of colon cancer patients using RT-PCR. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006, 11 (5): 385-389. 10.1007/s10147-006-0590-5.

Hiraiwa K, Takeuchi H, Hasegawa H, Saikawa Y, Suda K, Ando T, Kumagai K, Irino T, Yoshikawa T, Matsuda S, et al: Clinical significance of circulating tumor cells in blood from patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008, 15 (11): 3092-3100. 10.1245/s10434-008-0122-9.

Tuech JJ, Cervi C, Pessaux P, Villapadierna F, Bergamaschi R, Ronceray J, Arnaud JP: Early gastric cancer: univariate and multivariate analysis for survival. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999, 46 (30): 3276-3280.

Bonsing BA, Beerman H, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N, Fleuren GJ, Cornelisse CJ: High levels of DNA index heterogeneity in advanced breast carcinomas. Evidence for DNA ploidy differences between lymphatic and hematogenous metastases. Cancer. 1993, 71 (2): 382-391. 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2<382::AID-CNCR2820710219>3.0.CO;2-9.

Klijanienko J, el-Naggar AK, de Braud F, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, Rodriguez R, Itzhaki M, Russo A, Janot F, Luboinski B, Cvitkovic E: Tumor vascularization, mitotic index, histopathologic grade, and DNA ploidy in the assessment of 114 head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer. 1995, 75 (7): 1649-1656. 10.1002/1097-0142(19950401)75:7<1649::AID-CNCR2820750715>3.0.CO;2-E.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/346/prepub

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (23659308) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). The funding body played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We are grateful to all the patients and volunteers who donated blood to this study. We would like to thank Professor Toshiyoshi Fujiwara (Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Okayama, Japan) for providing helpful comments and suggestions; Mr Yasuo Urata (Oncolys BioPharma, Tokyo, Japan) for supplying the OBP-401; Dr Yukio Tsujino, Dr Toshiyuki Ozawa and Dr Akinori Masago (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) for their helpful support; and Dr Rebecca Devon (Genetics Unit and University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK) for critical review and editing of the manuscript. We are also most grateful to clinical staff.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Authors’ contributions

HI (Ito) conceived and designed the experiments, collected blood samples, performed the experiments, delivered clinical patients’ data, and performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of data. HI (Inoue) participated in the study design and performed interpretation of data. NS participated in the study design and performed interpretation of data. SK (Kimura) participated in the study design, maintained the equipment, including the test tubes, and performed data interpretation. KG, JS and KM performed the experiments and interpretation of data. SI performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of data. NO and HS managed clinical examination and performed treatment of individual patients. SK (Kudo) participated in the study design and coordination. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, H., Inoue, H., Sando, N. et al. Prognostic impact of detecting viable circulating tumour cells in gastric cancer patients using a telomerase-specific viral agent: a prospective study. BMC Cancer 12, 346 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-346

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-346