Abstract

Background

Tumor suppressor genes p53 and p16 INK4a and the proto-oncogene MDM2 are considered to be essential G1 cell cycle regulatory genes whose loss of function is associated with ESCC carcinogenesis. We assessed the aberrant methylation of the p16 gene and its impact on p16 INK4aprotein expression and correlations with p53 and MDM2 protein expressions in patients with ESCC in the Golestan province of northeastern Iran in which ESCC has the highest incidence of cancer, well above the world average.

Methods

Cancerous tissues and the adjacent normal tissue obtained from 50 ESCC patients were assessed with Methylation-Specific-PCR to examine the methylation status of p16. The expression of p16, p53 and MDM2 proteins was detected by immunohistochemical staining.

Results

Abnormal expression of p16 and p53, but not MDM2, was significantly higher in the tumoral tissue. p53 was concomitantly accumulated in ESCC tumor along with MDM2 overexpression and p16 negative expression. Aberrant methylation of the p16 INK4agene was detected in 31/50 (62%) of esophageal tumor samples, while two of the adjacent normal mucosa were methylated (P < 0.001). p16 INK4aaberrant methylation was significantly associated with decreased p16 protein expression (P = 0.033), as well as the overexpression of p53 (P = 0.020).

Conclusions

p16 hypermethylation is the principal mechanism of p16 protein underexpression and plays an important role in ESCC development. It is associated with p53 protein overexpression and may influence the accumulation of abnormally expressed proteins in p53-MDM2 and p16-Rb pathways, suggesting a possible cross-talk of the involved pathways in ESCC development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Esophageal cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Iran [1]. It is also considered the second most common type of cancer in both males and females in Golestan province of northeastern Iran (Age Standardized Rate: 22.57 in males and 19.89 in females in 105 persons/year) (unpublished data). This region is located in the "Esophageal Cancer Belt," stretching from China westward through central Asia to northern Iran, where there is a high incidence of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC)[2, 3]. Although several environmental risk factors are proposed for ESCC, the specific underlying genetic alterations have not been well defined for this region to date [3, 4].

Several genetic and epigenetic alterations are involved in esophageal carcinogenesis [5–7]. Investigation of alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes implicated in esophageal tumorigenesis may provide molecular markers for early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention[8].

Tumor suppressor genes P53 and p16 INK4aand the proto-oncogene MDM2 (Murine Double Minute 2), are considered to be essential G1 cell cycle regulatory genes and whose loss of function is associated with cancer development [9].

In response to DNA damage, p53 protein induces G1 cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [10]. Abnormalities of this gene, such as gene mutation, can lead to the loss of regulation of cell growth, DNA repair, or apoptosis, all of which are responsible for carcinogenesis [11]. The product of the MDM2 gene, which is induced by p53, appears to play a critical role in regulating the level of the wild-type p53 protein. It can bind to and inactivate the transcriptional activity of p53, resulting in the abrogation of p53 anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects, and consequently the deregulation of cell overgrowth, which leads to tumor development [11–13]. Acting as a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI), p16INK4abinds to and inhibits the activity of CDK4 and CDK6 and arrests the cell cycle in the G1/S phase in a p53-dependent pathway [14, 15].

DNA methylation in the normally unmethylated promoter region of tumor suppressor genes, such as p16 INK4a, is a critical mechanism for their inactivation and is commonly associated with the repression of gene transcription which promotes the development of cancers, including ESCC carcinogenesis [16–18]. Previous reports from Iran showed that p16 hypermethylation in the promoter region is a common mechanism for the inactivation of this gene in ESCC and gastric cancer development in Khorasan province of northeastern Iran [19, 20]. Aberrant p16 hypermethylation is also suggested as a possible epigenetic risk factor in familial ESCC [21].

In addition, p53 alterations, including the mutation of p53, have been identified as a frequent event in ESCC development in northeastern Iran [22, 23].

In the present study, we examined the methylation status of the p16 gene, in 50 ESCC patients using Methylation Specific PCR (MSP) assay. p16, p53 and MDM2 protein expression was assessed to identify the association of p16 INK4agene methylation with the expression of these cell cycle proteins in a population with a high incidence of ESCC in northeastern Iran.

Methods

Study population and sample collection

A total of 50 ESCC patients (ages ranging from 35-83 years) were recruited from May 2006 to June 2007, from among patients referred to the two main referral oncology centers in northeastern Iran: Atrak clinic, a referral center for upper GI cancers in Golestan province, and Omid Oncology Hospital, referral oncology hospital in northeastern Iran. It is estimated that approximately 95% of upper GI cancer patients in this region are referred to Atrak clinic [24]. Patients did not receive any adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy or chemotherapy) or blood transfusions. Follow up carried out 6 to 24 months afterwards. Demographic characteristics and information about social habits, including the smoking or consumption of cigarettes, the hookah and nass (a mixture of tobacco, ash, and lime) [4], were obtained by trained interviewers using a standard questionnaire. All patients underwent upper GI endoscopy. Tissue samples of esophageal tumor and macroscopically adjacent normal tissue from a site, remote from the tumor, were dissected and fixed in 70% alcohol and embedded in paraffin. The presence of normal and tumor tissue was assessed by histological evaluation. The Research Ethics Committees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Mashhad University of Medical Sciences approved the study design. All eligible patients signed a written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

DNA Extraction

Areas of the tumor in which tumor cells represented >70% of all cells were extracted. Genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues by use of xylene and alcohol. After digestion by proteinase K, DNA was extracted and purified by the phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol method and precipitated in ethanol, as previously described[20].

Bisulfite modification

Bisulfite modification of DNA results in conversion of unmethylated cytosine residues into uracil, whereas, the methylated cytosine residues, remains unchanged.

Briefly, 2 μg of DNA was denatured in 3 mol/L NaOH (2 μL) for 10 min at 50°C and then modified by adding a 500 μl of a freshly prepared bisulfite solution (2.5 M sodium bisulfate and 125 mM hydroquinone) following to an incubation for 12 h at 50°C. DNA samples were desalted through a column (Wizard DNA Clean-Up System, Promega), and then treated with 3 mol/L NaOH (5 μL) for 10 min at 37°C, followed by precipitation with 75 μl ammonium acetate (5 M). The pellet was washed with 2.5 volumes of ethanol, dried, and re-suspended in 20 μl tris (pH 8.0, 5 mM), then stored at -70° until used for MSP.

Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP)

After bisulfite treatment, DNA samples were assayed by methylation-specific PCR. The PCR mixture was prepared in a 25 μl volume containing 1× buffer (Finzymes, Finland) with 2 mmol/L of MgCl2, 500 nmol/L of each primer (previously described sequences[20]), 0.2 mmol/L of dNTPs, 1 U of Hot Start Taq polymerase (Finzymes, Finland), and bisulfite-modified DNA. DNA amplification was performed in a thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). The PCR amplification consisted of an initial hot-start step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles (45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 60°C, 60 s at 72°C), and a final 10 min extension at 72°C. Each MSP was repeated at least twice. In addition to a negative control, DNA from L132 and H1299 cells were used as a positive control for unmethylated and methylated alleles, respectively. PCR products were loaded on 2.5% agarose gel and 6% poly-acrylamide gel, stained with silver nitrate dyes and visualized under UV illumination.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin embedded sections (3 μm thick) of esophageal tumor and adjacent normal tissue were used to perform IHC reaction. Briefly, the sections were mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides and dried at 60°C for 1 hour. The sections were dewaxed and rehydrated in a xylene-ethanol series and boiled in the Target Retrieval Solution of Dako (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) in a microwave oven for 40 min. After endogenous peroxidase blocking, the following antibodies (Abs) were used: primary mouse monoclonal p16 INK4aantibody (C-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) (IgG2a, 200 μg/ml) at a working dilution of 1/1600, at 4°C overnight; mouse anti-human p53 monoclonal antibody (clone: DO-7, isotype IgG2b) (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), incubation for 45 min at 37°C with a 1:50 dilution; and, for MDM2, IgM mouse monoclonal clone 1B10 (carboxy terminus of MDM2) was used (Novocastra Laboratories, New Castle, UK) with a 1:100 dilution, incubated overnight. After two washes in PBS, sections were incubated with EnVisionTM+System/HRP, Rabbit/Mouse (DAB+) (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA), a secondary antibody. The immunoreactivity was detected using diaminobenzidine (DAB) (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) as the final chromogen. Finally, sections were counterstained with Meyer's Hematoxylin, dehydrated through a sequence of increasing concentrations of alcoholic solutions and cleared in xylene. During each IHC assay, proof slides were coupled with negative control slides on which the primary antibody was omitted. P16-positive and p53-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma was used as positive controls in every section. The cutoff values for abnormal expression were determined as follows: MDM2 > 30% [25]; p53 > 5% [26]; p16 < 5% [9].

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The correlation between two variables was evaluated using Pearson's chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. Survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Using the log-rank test, we compared the survival of ESCC patients according to various clinicopathological factors. A 2-sided P value < 0.05 was considered as the significant statistical level.

Results

Fifty ESCC patients (ages ranging from 35 to 83 years; with the mean age of 59.02 ± 11.41 years) were enrolled in this study. Twenty five (50%) patients were men and 25 were women with the male to female ratio of 1. Tumor sizes ranged from 2 to 12 cm, with a mean diameter was 4.97 ± 2.13 cm. Clinicopathological characteristics of the ESCC patients are summarized in table 1.

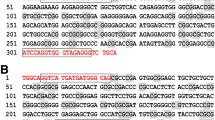

The methylation status of 5' CpG island of the p16 gene was detected in 31/50 (62%) esophageal tumor samples, while two of the adjacent normal mucosa were methylated (P < 0.001). No significant association was found between the methylation status of the p16 gene and the factors studied, including age, sex, tumor histopathology, tumor site and size, and opium and tobacco use (cigarette and hookah smoking, Nass chewing) (Table 1). Figure 1 represents MSP analysis of p16 gene.

MSP analysis of p16 gene in ESCC patients. DNA from H1299 cells served as a positive control for hypermethylated DNA and L132 as a positive control for unmethylated DNA. Patient 17 (p17) and patient 25 (p25) were hypermethylated, which revealed 150 bp bands (M) with hypermethylated primers. Patient 12 (p12) and patient 9 (p9) were not methylated, having only unmethylated band (U).

Immunohistochemical staining

IHC staining of p16, p53 and MDM2 are represented in figure 2.

a) Immunohistochemical staining of p16, p53 and MDM2

The negative expression of the p16 protein was detected in 28/50 (56%) tumors and only 7/50 (14%) normal tissues (P < 0.001).

The positive expression of p53 and MDM2 proteins in the nuclei was detected in 31/50 (62%) and 21/50 (42%) tumor tissues and in 7/50 (14%) and 30/50 (60%) normal esophageal tissues, respectively. There was a significant difference between tumor and normal tissues for p53 staining (P = 0.001), but not for MDM2. The histological grade of differentiation was not associated with the IHC staining of p16, p53 and MDM2.

b) Concomitant p16, p53 and MDM2protein expression in ESCC

The overexpression of MDM2 was not significantly associated with the abnormal expression of p53. There was neither significant correlation between p16 and p53, nor between p16 and MDM2 immunoreactivity in esophageal tumor and normal samples, independently. Concomitant abnormal accumulation of the p53 protein with either MDM2 overexpression or abnormal underexpression of p16 was significantly more frequent in tumoral tissue compared to normal tissue; p16-/p53+ immunostaining was detected in 20/50 (40%) tumors and in none of the normal tissues; whereas the opposite combination (p16+/p53-) was found in 11/50 (22%) tumors and 36/50 (72%) normal specimens, with a statistically significant difference between tumor and normal samples in these subgroups (P < 0.001). In tumoral and normal tissues, the proportion of p53+/MDM2+ was 16/50 (32%) and 2/50 (4%), while p53-/MDM2- was detected in 14/50 (28%) and 14/50 (28%) respectively, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). On the other hand, with MDM2+/p16-, there was not a significant difference in tumors compared to normal tissues (P = 0.078).

We also investigated the association between the p16/p53/MDM2 profile and tobacco use, histology of tumor, and p16 methylation status in ESCC. The samples were divided into four groups according to the number of alterations detected. The p16-/p53+/MDM2+ immunoprofile was only observed in the tumor tissues and not in the normal adjacent tissue (P < 0.001). Similarly we observed this profile more frequently in p16-methylated tumors (P = 0.035). We did not find any significant association between tobacco consumption and different histological subtypes with the different immunoprofiles. (Table 2)

Correlation between p16, p53 and MDM2 immunoreactivity, and hypermethylation of p16

Twenty one out of thirty one (67.7%) methylation-positive esophageal tumors showed a complete lack of immunoreactivity of p16. Twelve out of nineteen (63.2%) of unmethylated tumors represented diffuse immunoreactivity, whereas 7/19 (36.8%) of unmethylated tumors were not immunostained for p16. p16 negative staining was significantly correlated with p16 methylation (P = 0.033). Significant association was observed between abnormal accumulation of p53 and p16 hypermethylation (p = 0.020). Moreover, p16 methylation was more frequent in cases with concomitant accumulation of p53 and loss of p16 proteins i.e. 17/20 (85%), compared to the cases with p16 expressed and p53 negative, 4/11 (36.36%) (P = 0.01). p16 methylation was not associated with MDM2 overexpression. (Table 1)

Patients' Survival

The 6-months, 1- year, and 2-year survival rates were 78%, 43%, and 28% in tumors with p16 hypermethylation and 43%, 14%, and 0% in tumors without p16 hypermethylation, respectively. The median survival duration of patients with p16 hypermethylation was 8 months, whereas it was 5 months for patients without hypermethylation. The 6 months, 1-year, and 2-year survival rates were 67%, 33%, and 33% in cases with p16 expression group and 62%, 31% and 18% in the cases with loss of p16, respectively. The median survival duration of patients with and without loss of p16 expression was 8 and 10 months, respectively.

There was no statistically significant difference in survival rates based on the p16 hypermethylation status or p16 protein expression.

Discussion

Golestan province in northeastern Iran has a high incidence of ESCC, which is well above the world average. To better understand some aspects of the complex genetic/epigenetic alterations in this high incidence region, we investigated the role of some components of p53-MDM2 and p16-Rb pathways of cell cycle regulation and their possible cross-talk in ESCC tumorigenesis. Thus, we assessed p16 hypermethylation as an important mechanism of gene silencing, its impact on the p16 protein expression, along with its correlation with the p53 and MDM2 protein expression.

We showed that p16 protein expression was significantly associated with methylation of the p16 gene, indicating that p16 methylation may play a critical role in the silencing of this important tumor suppressor gene. On the other hand, significant differences in both methylation and loss of protein expression of p16 in tumoral tissue compared to the normal tissue confirms the critical role of these genetic and epigenetic alterations in the development of ESCC in this high-incidence region. In this study, p16 hypermethylation was observed in 62% of the patients. Previous reports of p16 methylation varied between 40-90% among ESCC patients in the Far East. Xing et al [27] studied 40 ESCC patients and detected the p16 gene hypermethylation in 40% of tumor samples. Whereas, Hardie et al [28] and Hibi et al [29] reported promoter methylation of the p16 gene in 85% (18/21) and 82% (31/38) of esophageal carcinoma, respectively. Wang et al [30] showed the aberrant hypermethylation of p16, as a frequent event, in 88% of ESCC patients in China. Abbaszadegan et al reported 73.3% p16 gene methylation in ESCC samples in Khorasan, another province in the northeastern Iran. In support of their data, this study indicates the critical role of p16 methylation in ESCC development in this high risk region [19].

In this study, we also examined p16 methylation in normal tissue adjacent to tumor, in order to clarify whether p16 methylation may have been occurred in the background of tumors. We showed that in two ESCC patients, p16 methylation occurred not only in the tumoral cells but also in the corresponding normal tissue. In the normal tissue of one of the two, p16 protein was not expressed. In line with our data on p16 methylation in normal tissue, Hibi et al presented one case of p16 methylation in the normal tissue in addition to WBCs of peripheral blood. They suggested that individuals with p16 promoter methylation of normal tissue might be prone to development of cancer. Furthermore, other studies have provided evidence of p16 methylation in normal tissue. p16 methylation of normal tissues, as a rare event, was also shown by Esteller et al [31]. Guan et al [32]reported the p16 methylation of transitional mucosa in 2/8 colon cancer patients. We can speculate that the presence of p16 methylation in normal tissue of these two studied ESCC patients may prone them to trigger tumor formation in these tissues. Although p16 hypermethylation most often occurs in the late preneoplastic stages (i.e. dysplasia) [33], it seems that in a small proportion of individuals, methylation may rarely occur in the normal tissue of esophagus. Environmental factors, previously reported as influencing aberrant hypermethylation, such as exposure to carcinogens or dietary factors, [34–37], along with a possible genetic predisposition, such as DNA methyltransferase activation [38], may be responsible for the epigenetic alterations and methylation induction in the normal tissue of this small proportion. However, further large-scale studies are required to focus on this issue and validate the probable impact of life-style and environmental factors and possible genetic predispositions on the methylation status of normal esophageal tissue.

Regarding p16 immunostaining, we did not detect hypermethylation in 7 out of 28 ESCC tumor tissues (25%) with negative p16 immunostaining. This suggested that other molecular mechanisms, such as point mutation, homozygous deletion or loss of heterozygosity, may contribute to p16 gene inactivation [39–41]. In 20% of ESCCs (10/50), p16 protein expression was accompanied by positive p16 hypermethylation. This can possibly be explained by hemi-methylation of the p16 gene. It may also reflect the high sensitivity of the MSP method, i.e. 0.1% methylated DNA, which would indicate that tumor samples with a low proportion of methylated DNA could be considered as methylation positive by MSP even though they may withhold p16 immunoreactivity due to unmethylated tumor cells in the same sample [42].

It has been hypothesized that p53 alterations may concomitantly occur with alterations in p16 INK4ain carcinogenesis [43]. As for the p53-MDM2 pathway, when the p16 methylation status was compared with the p53 and MDM2 protein expression in ESCC patients, we observed that ESCC tumors with p16 epigenetic inactivation more often harbored increased levels of p53 protein expression. To our knowledge, this is the first report indicating the association between p16 hypermethylation and p53 protein accumulation in ESCC. Lee et al detected abnormal accumulation of p53, along with p16 promoter hypermethylation in colon cancer despite the inverse correlation between them as reported by other previous studies [44]. Esteller et al showed that p53 overexpression was independent of p16 methylation status in colorectal cancer [45]. Ishii et al reported more extensive DNA methylation in neoplastic lesions of ESCC with a p53 mutation than in those with wild-type p53, when assessing the promoter hypermethylation of 14 tumor suppressor genes; however p16 hypermethylation was not independently associated with p53 mutation[46].

These observations may help us address the occurrence of combined molecular mechanisms, which are likely to play a major role in ESCC tumor progression. Since cell populations of the primary neoplasm are heterogeneous, a single marker cannot specifically and accurately predict the behavior of the tumor [47]. Abnormal p53 expression occurs concomitantly with abnormally expressed p16 or MDM2 proteins in the tumor. On the other hand, p16 hypermethylation is associated with a larger accumulation of abnormal protein expression in both p16-Rb and p53-MDM2 pathways. All these findings in addition to correlation between p16 hypermethylation and p53 abnormal accumulation, indicate a possible overlap and cross-talk between the involved pathways.

Although it has been reported that p16 hypermethylation is a predisposing epigenetic trait in the familial ESCC in Iran [21], the role of other factors such as environmental factors has not yet been ruled out. It has been reported that high-level exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may contribute to the high incidence of ESCC in the northeastern Iran [4]. Concomitant p16 hypermethylation and p53 overexpression may be a consequence of various environmental, dietary or lifestyle factors peculiar to this region, associated with an increased susceptibility to ESCC. However due to the lack of a precise evaluation of environmental exposures in this study, we could not strongly deduce any correlation between these factors and p16 methylation or protein expression status, as well as p53 and MDM2 overexpression.

Conclusion

In summary, we conclude that p16 gene silencing caused by hypermethylation of CpG islands may be a major mechanism in the ESCC development. It is associated with p53 protein overexpression in the ESCC patients of northeastern Iran. This is the first study indicating the association between p16 hypermethylation and p53 protein overexpression. The impact of p16 hypermethylation on accumulation of abnormally expressed proteins in the p53-MDM2 pathway, along with the observed concomitant accumulation of p53 with either MDM2 overexpression or decreased p16 expression, suggests a possible cross-talk of the involved pathways in ESCC development in northeastern Iran. Further studies of the methylation status of various cancer-related genes in a large sample size, accompanied by the assessment of exposure to the potentially harmful environmental factors, are needed to better elucidate the genetic changes occurring in ESCC carcinogenesis and tumor progression in this high risk population.

References

Mousavi SM, Gouya MM, Ramazani R, Davanlou M, Hajsadeghi N, Seddighi Z: Cancer incidence and mortality in Iran. Ann Oncol. 2009, 20 (3): 556-563. 10.1093/annonc/mdn642.

Mahboubi E, Kmet J, Cook PJ, Day NE, Ghadirian P, Salmasizadeh S: Oesophageal cancer studies in the Caspian Littoral of Iran: the Caspian cancer registry. Br J Cancer. 1973, 28 (3): 197-214.

Islami F, Kamangar F, Aghcheli K, Fahimi S, Semnani S, Taghavi N, Marjani HA, Merat S, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Pourshams A, et al: Epidemiologic features of upper gastrointestinal tract cancers in Northeastern Iran. Br J Cancer. 2004, 90 (7): 1402-1406. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601737.

Kamangar F, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM, Saidi F: Esophageal cancer in Northeastern Iran: a review. Arch Iran Med. 2007, 10 (1): 70-82.

Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ: Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349 (23): 2241-2252. 10.1056/NEJMra035010.

Chen X, Yang CS: Esophageal adenocarcinoma: a review and perspectives on the mechanism of carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Carcinogenesis. 2001, 22 (8): 1119-1129. 10.1093/carcin/22.8.1119.

El-Rifai W, Powell SM: Molecular biology of gastric cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002, 12 (2): 128-140. 10.1053/srao.2002.30815.

Arora S, Mathew R, Mathur M, Chattopadhayay TK, Ralhan R: Alterations in MDM2 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: relationship with p53 status. Pathol Oncol Res. 2001, 7 (3): 203-208. 10.1007/BF03032350.

Tsuda H, Hashiguchi Y, Nishimura S, Kawamura N, Inoue T, Yamamoto K: Relationship between HPV typing and abnormality of G1 cell cycle regulators in cervical neoplasm. Gynecol Oncol. 2003, 91 (3): 476-485. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.019.

Gottlieb TM, Oren M: p53 in growth control and neoplasia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996, 1287 (2-3): 77-102.

Dong M, Ma G, Tu W, Guo KJ, Tian YL, Dong YT: Clinicopathological significance of p53 and mdm2 protein expression in human pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005, 11 (14): 2162-2165.

Lev Bar-Or R, Maya R, Segel LA, Alon U, Levine AJ, Oren M: Generation of oscillations by the p53-Mdm2 feedback loop: a theoretical and experimental study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97 (21): 11250-11255. 10.1073/pnas.210171597.

Saito H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, Kaibara N: The expression of murine double minute 2 is a favorable prognostic marker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without p53 protein accumulation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002, 9 (5): 450-456. 10.1007/BF02557267.

Cordon-Cardo C: Mutations of cell cycle regulators. Biological and clinical implications for human neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 1995, 147 (3): 545-560.

Jang SJ: [Cell cycle regulators as prognostic predictor of colorectal cancers]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004, 44 (6): 346-349.

Herman JG, Baylin SB: Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349 (21): 2042-2054. 10.1056/NEJMra023075.

Sato F, Meltzer SJ: CpG island hypermethylation in progression of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer. 2006, 106 (3): 483-493. 10.1002/cncr.21657.

Macaluso M, Paggi MG, Giordano A: Genetic and epigenetic alterations as hallmarks of the intricate road to cancer. Oncogene. 2003, 22 (42): 6472-6478. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206955.

Abbaszadegan MRAS, Raziee HR, Ghafarzadegan K, Ghavamnasiry MR: p16/INK4a promoter hypermethylation in serum, blood and tumor of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. IJBMS. 2004, 6 (4): 6-

Abbaszadegan MR, Moaven O, Sima HR, Ghafarzadegan K, A'Rabi A, Forghani MN, Raziee HR, Mashhadinejad A, Jafarzadeh M, Esmaili-Shandiz E, et al: p16 promoter hypermethylation: a useful serum marker for early detection of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008, 14 (13): 2055-2060. 10.3748/wjg.14.2055.

Abbaszadegan MR, Raziee HR, Ghafarzadegan K, Shakeri MT, Afsharnezhad S, Ghavamnasiry MR: Aberrant p16 methylation, a possible epigenetic risk factor in familial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005, 36 (1): 47-54. 10.1385/IJGC:36:1:047.

Sepehr A, Taniere P, Martel-Planche G, Zia'ee AA, Rastgar-Jazii F, Yazdanbod M, Etemad-Moghadam G, Kamangar F, Saidi F, Hainaut P: Distinct pattern of TP53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Iran. Oncogene. 2001, 20 (50): 7368-7374. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204912.

Biramijamal F, Allameh A, Mirbod P, Groene HJ, Koomagi R, Hollstein M: Unusual profile and high prevalence of p53 mutations in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from northern Iran. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (7): 3119-3123.

Taghavi NND, Merat S, Yazdanbod A, Hormazdi M, Sotoudeh MSS, Eslami F, Marjani HA, Fahimi S, Khademi H, Malekzadeh R: Epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal cancers in Iran: a sub site analysis of 761 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13 (40): 5367-5370.

Mathewa RAS, Khannaa R, Mathurb M, Shuklac NK, Ralhana R: Alterations in p53 and pRb pathways and their prognostic significance in oesophageal cancer. European Journal of cancer. 2002, 38 (6): 832-841. 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00007-2.

Zali MR, Moaven O, Asadzadeh Aghdaee H, Ghafarzadegan K, Jami Ahmadi K, Farzadnia K, Arabi A, MR A: Clinicopathological significance of E-cadherin, β-catenin and p53 expression in gastric adenocarinoma. JRMS. 2009, 14 (4): 239-247.

Xing EP, Nie Y, Song Y, Yang GY, Cai YC, Wang LD, Yang CS: Mechanisms of inactivation of p14ARF, p15INK4b, and p16INK4a genes in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999, 5 (10): 2704-2713.

Hardie LJ, Darnton SJ, Wallis YL, Chauhan A, Hainaut P, Wild CP, Casson AG: p16 expression in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: association with genetic and epigenetic alterations. Cancer Lett. 2005, 217 (2): 221-230. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.025.

Hibi K, Taguchi M, Nakayama H, Takase T, Kasai Y, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A: Molecular detection of p16 promoter methylation in the serum of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001, 7 (10): 3135-3138.

Wang J, Sasco AJ, Fu C, Xue H, Guo G, Hua Z, Zhou Q, Jiang Q, Xu B: Aberrant DNA methylation of P16, MGMT, and hMLH1 genes in combination with MTHFR C677T genetic polymorphism in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17 (1): 118-125. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0733.

Esteller M, Herman JG: Cancer as an epigenetic disease: DNA methylation and chromatin alterations in human tumours. J Pathol. 2002, 196 (1): 1-7. 10.1002/path.1024.

Guan RJ, Fu Y, Holt PR, Pardee AB: Association of K-ras mutations with p16 methylation in human colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1999, 116 (5): 1063-1071. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70009-0.

Kang GH, Lee S, Kim JS, Jung HY: Profile of aberrant CpG island methylation along the multistep pathway of gastric carcinogenesis. Lab Invest. 2003, 83 (5): 635-641.

Cui X, Wakai T, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K, Hirano S: Chronic oral exposure to inorganic arsenate interferes with methylation status of p16INK4a and RASSF1A and induces lung cancer in A/J mice. Toxicol Sci. 2006, 91 (2): 372-381. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj159.

Marsit CJ, Karagas MR, Danaee H, Liu M, Andrew A, Schned A, Nelson HH, Kelsey KT: Carcinogen exposure and gene promoter hypermethylation in bladder cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2006, 27 (1): 112-116. 10.1093/carcin/bgi172.

Keyes MK, Jang H, Mason JB, Liu Z, Crott JW, Smith DE, Friso S, Choi SW: Older age and dietary folate are determinants of genomic and p16-specific DNA methylation in mouse colon. J Nutr. 2007, 137 (7): 1713-1717.

Fang M, Chen D, Yang CS: Dietary polyphenols may affect DNA methylation. J Nutr. 2007, 137 (1 Suppl): 223S-228S.

Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, Jones PA: The human DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: coordinate mRNA expression in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27 (11): 2291-2298. 10.1093/nar/27.11.2291.

Van Zee KJ, Calvano JE, Bisogna M: Hypomethylation and increased gene expression of p16INK4a in primary and metastatic breast carcinoma as compared to normal breast tissue. Oncogene. 1998, 16 (21): 2723-2727. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201794.

Hui AM, Sakamoto M, Kanai Y, Ino Y, Gotoh M, Yokota J, Hirohashi S: Inactivation of p16INK4 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1996, 24 (3): 575-579. 10.1002/hep.510240319.

Shim YH, Kang GH, Ro JY: Correlation of p16 hypermethylation with p16 protein loss in sporadic gastric carcinomas. Lab Invest. 2000, 80 (5): 689-695.

Shim YH, Park HJ, Choi MS, Kim JS, Kim H, Kim JJ, Jang JJ, Yu E: Hypermethylation of the p16 gene and lack of p16 expression in hepatoblastoma. Mod Pathol. 2003, 16 (5): 430-436. 10.1097/01.MP.0000066799.99032.A7.

Markl ID, Jones PA: Presence and location of TP53 mutation determines pattern of CDKN2A/ARF pathway inactivation in bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1998, 58 (23): 5348-5353.

Lee M, Sup Han W, Kyoung Kim O, Hee Sung S, Sun Cho M, Lee SN, Koo H: Prognostic value of p16INK4a and p14ARF gene hypermethylation in human colon cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2006, 202 (6): 415-424. 10.1016/j.prp.2005.11.011.

Esteller M, Gonzalez S, Risques RA, Marcuello E, Mangues R, Germa JR, Herman JG, Capella G, Peinado MA: K-ras and p16 aberrations confer poor prognosis in human colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 19 (2): 299-304.

Ishii T, Murakami J, Notohara K, Cullings HM, Sasamoto H, Kambara T, Shirakawa Y, Naomoto Y, Ouchida M, Shimizu K, et al: Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma may develop within a background of accumulating DNA methylation in normal and dysplastic mucosa. Gut. 2007, 56 (1): 13-19. 10.1136/gut.2005.089813.

Esteller M: Relevance of DNA methylation in the management of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003, 4 (6): 351-358. 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01115-X.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/138/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Digestive Diseases Research Center (DDRC) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the scientific collaborators of DDRC, Division of Human Genetics of Avicenna Research Institute of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, and the National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology. The results described in this paper were part of a Ph.D. student dissertation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NT carried out data collection, the molecular genetic studies, designed the questionnaire, participated in designing the study, and drafted the manuscript. FB participated in the study design and coordination. MS participated in the study design and coordination, participated in data interpretation and carried out immunohistochemistry study. HK performed the statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and participated in drafting the manuscript. RM general supervision of the research group, management of data collection and questionnaire development, participated in the study design and coordination. OM participated in epigenetic study, interpretation of data, and scientifically revised the manuscript. BM participated in the immunohistochemistry study. AA carried out epigenetic studies. MRA conceived of the study, participated in the study design and coordination, and scientifically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Taghavi, N., Biramijamal, F., Sotoudeh, M. et al. p16 INK4a hypermethylation and p53, p16 and MDM2 protein expression in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Cancer 10, 138 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-138

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-138