Abstract

Background

Loss of activity of tumor suppressor genes is considered a fundamental step in a genetic model of carcinogenesis. Altered expression of the p53 and the Deleted in Colon Cancer (DCC) proteins has been described in gastric cancer and this event may have a role in the development of the disease. According to this hypothesis, we investigated the p53 and the DCC proteins expression in different stages of gastric carcinomas.

Methods

An immunohistochemical analysis for detection of p53 and DCC proteins expression was performed in tumor tissue samples of patients with UICC stage I and II gastric cancer. For the purpose of the analysis, the staining results were related to the pathologic data and compared between stage categories.

Results

Ninety-four cases of gastric cancer were analyzed. Disease stage categories were pT1N0 in 23 cases, pT2N0 in 20 cases, pT3N0 in 20 cases and pT1-3 with nodal involvment in 31 cases. Stage pT1-2N0 tumors maintained a positive DCC expression while it was abolished in pT3N0 tumors (p <.001). A significant higher proportion of patients with N2 nodal involvement showed DCC negative tumors. In muscular-invading tumors (pT2-3N0) the majority of cases showed p53 overexpression, whereas a significantly higher proportion of cases confined into the mucosa (pT1N0) showed p53 negative tumors. Also, a higher frequency of p53 overexpression was detected in cases with N1 and N2 metastatic lymphnodal involvement.

Conclusions

Altered expression of both DCC and p53 proteins is detectable in gastric carcinomas. It seems that loss of wild-type p53 gene function and consequent p53 overexpression may be involved in early stages of tumor progression while DCC abnormalities are a late event.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Experimental data support the hypothesis that tumors may originate from the accumulation of genetic defects. In a model of multi-step carcinogenesis, mutations of the Deleted in Colon Cancer (DCC) and the p53 tumor suppressor genes with functional abnormalities of the proteins they encode may be involved in the development of a variety of tumors [1].

In gastric cancer, p53 abnormalities have been observed in 5% to 70% of cases [2]. The most common are missense mutations which usually prolong the half-life of the p53 abnormal protein causing its nuclear accumulation and the detection by immunohistochemistry. Experimental data suggest a chronology for the loss of p53 function and similarities with the carcinogenetic model of colorectal cancer [3, 4].

The DCC gene encodes for a membrane-bound protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which can be detected by immunohistochemistry with a commercial monoclonal antibody [5]. Abnormalities of the DCC tumor suppressor gene and abolished DCC function may be critically involved in the development of gastric cancer [6–11]. Recent studies found that the DCC gene is involved in the regulation of axonal development as a component of the Netrin-1 receptor, and some investigations failed to demonstrate the role of DCC in the carcinogenetic process [12]. More recently, the DCC gene product was found to induce apoptosis activating caspase-3 and high levels of DCC expression were associated to an effective apoptotic process [13, 14]. Thus, DCC may function as tumor suppressor gene which controls programmed cell death [13].

In the malignant progression of this disease, early investigations have suggested that the DCC gene damage may occur after the loss of heterozygosity on the p53 gene location [6]. However, the consecution and timing of these events is still unclear [7–10], and the role and the chronology of p53 and DCC alterations in the genesis and progression of gastric cancer are still under investigation [11].

On these bases, we have performed a combined analysis of p53 and DCC proteins expression in consecutive cases of gastric carcinoma. Patients with UICC stages I and II were considered eligible for the analysis, staining results were correlated with the depth of tumor invasion into the gastric wall and nodal involvement.

Materials and Methods

The study population consisted of patients referred to our Insitutions after radical surgery for stage pT1-3N0M0 and pT1-3N1-2M0 gastric cancer. The analysis was carried out on tumor tissue from the primary tumors and all the cases were reviewed independently by two pathologists.

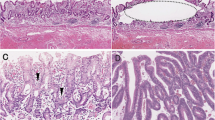

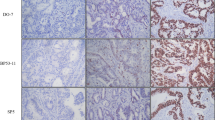

Paraffin-embedded tumor blocks were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for DCC and p53 proteins expression using a standard avidin-biotynilated peroxidase complex (ABC) staining method [15]. Sections (4 m thick) were deparaffinised in xylene, rehydratated in a graded ethanol series and incubated in 3% hydrogen-peroxide for 20 min. Specimens were placed in a plastic Coplin jar containing citric buffer and heated 4 × 2.5 min in a microwave processor at 95°C. After the microwave processing, sections were left in the Coplin jar at room temperature for 30 min. Specimens were covered with normal goat serum for 15 min to reduce nonspecific staining and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with a murine monoclonal antibody for p53 (clone DAKO D07, Copenhagen, Denmark; dilution 1:75) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody for DCC (clone G97-449, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA at 1:500 dilution). The sections were washed with Tris-buffered saline, incubated with a 1:100 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G at room temperature for 30 min, and then covered with a 1:100 dilution of streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex at room temperature for 30 min. The antibody was localized with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB). Tissue sections were counterstained with light haematoxylin, dehydrated with ethanol and mounted under a coverslip.

In each case, the entire section was systemically examined on high-power fields (x400) for DCC and p53 immunoreactivity. The level of immunoreactivity was expressed as the percentage of stained cancer cells (0% to 100%); the 25% and the 5% cut-off values were adopted for DCC and p53 respectively [16, 17].

Statistical analysis was performed to correlate the results of DCC and p53 staining to the pathologic features of tumors. In a preliminary step, diffuse and intestinal histotypes were analyzed for DCC and p53 expression; both subtypes were included in the final analysis in the case of no significant distribution of positive and negative cases between the two histologies.

According to the cut-off values, the results of DCC and p53 analyses were used as dichotomized (categorical) variable. Contingency tables were analyzed by the Fisher's exact test or the Chi-square test as appropriate. All the values were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as p < .05.

Results

The analysis was performed in tumors of 94 out of 100 eligible patients who underwent radical surgery for gastric cancer. Six cases (5%) were exluded due to unassessable archival tumor tissue. Stage disease was: pT1-3N0 in 63 patients, pT1-3N1 in 15 patients and pT1-3N2 in 16 patients. Clinico-pathologic features of the 94 patients are reported in Table 1.

DCC analysis showed a clear dichotomized distribution of positive and negative cases; negative cases showed 0% to <5% stained cells, while positive cases showed > 75% stained cells. Thus, the 25% cut-off value was unnecessary and we observed an "all or nothing"-like phenomenon as reported by Shibata et al [16]. The DCC wild-type protein was detected in 58 cases (62%) and it was absent in 36 cases (38%).

In the present series, 24 cases were categorized p53 negative (26%); 18 cases showed no nuclear p53 expression and 24 cases less or equal 5% of stained cell nuclei. The p53 overexpression was found in 70 cases (74%) and the mean percentage of p53 overexpressing cells was 45%.

Both diffuse and intestinal subtypes showed abolished DCC expression and/or p53 overexpression. No statistically significant distribution of DCC/p53 postive and negative cases was observed in the subset analysis of diffuse and intestinal subtypes (data not shown). The results of the DCC analysis in tumors of 63 patients with node-negative disease are summarized in Table 2. The majority of pT1N0 and pT2N0 cases maintained positive DCC protein expression while it was significantly reduced in pT3N0 cases (p = .001). A significantly higher number of node-negative tumors maintained DCC expression (p = .007), while abolished DCC expression was significantly related to a more advanced lymphnodal involvement; in fact, the majority of N2 cases showed DCC negative tumors (p = .001) (Table 3).

In Table 4 are reported the results of the p53 analysis in the 63 patients with node-negative tumors. In muscular-invading tumors (pT2-3N0) the majority of cases showed p53 overexpression, whereas a significantly higher proportion of cases confined into the mucosa (pT1N0) showed p53 negative tumors (p = .001). Also, a higher frequency of p53 overexpression was detected in cases with metastatic lymphnodal involvement (p = .003 without major differences between N1 and N2 cases (Table 5).

Discussion

In 1992, Uchino et al [6] first reported experimental data supporting the role of DCC abnormalities in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. Interestingly, they found that loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the DCC gene occurred irrespective of the stage of disease. Fang et al. [7] found that LOH of the DCC gene was a late phenomenon and associated with the malignant progression of gastric cancer. Wu et al [8] described LOH of the DCC gene in advanced intestinal gastric cancer and infrequently in early or advanced diffuse histotype. Also, the analysis of DCC mRNA expression levels showed correlation with the clinicopathologic features of gastric carcinomas which had significantly lower expression than normal tissues [9, 10]. Available data are consistent with a relationship between DCC impaired function and the development of gastric cancer, however, the chronology of this event is unclear yet [11].

In the present study, the majority of pT1-2 tumors maintained the DCC protein expression which was significantly reduced in T3 tumors, or in cases with lymphnodal involvement. These data support the hypothesis that loss of wild-type DCC function is a late event in the progression of gastric cancer, and the gene protein product is reduced in more advanced stages of the disease. Actually, Wu et al [8] found infrequent LOH of the DCC gene in the advanced diffuse histotype; this observation was not confirmed by Fang et al [7] who did not find any correlation between LOH of the DCC gene and histologic subtypes of gastric carcinomas.

Gastric cancer and colorectal cancer may share a genetic model of carcinogenesis [3–7], and alterations of the p53 tumor suppressor genes may happpen at some point of the malignant progression preceding or following the DCC damage. In colorectal cancer, the Vogelstein's model of multi-step carcinogenesis suggests that the DCC gene damage precedes abnormalities of the p53 gene [2], however, both DCC and p53 aberrations seem to be late events in the development of colorectal cancer [18].

In gastric cancer, available data suggest that a p53 impaired function represent an early event in the carcinogenetic process [19]. Also, p53 accumulation positively correlated with increasing tumor stage, size and lymphnodal involvment [19–22]. Oiwa et al [23] found that p53 gene abnormalities and protein overexpression may play an important role in cancer expansion, providing tumors with a potential of vertical growth into the gastric wall. Wu et al [8] and Kataoka et al [11] attempted a combined analysis of the p53 and the DCC status in gastric cancer. Their findings on the timing of genetic damage are discordant, notably, in the largest series by Wu et al [8], p53 abnormalities resulted an early event and LOH of the DCC gene a late event.

In the present series, the phenomenon of p53 overexpression correlated with the tumor progression from the intra-mucosal stage to the muscular-invading stage, while abolished DCC function was detected in tumors deeply infiltrating the gastric wall or with lymphnodal involvement. These findings support the hypothesis that abnormalities of both tumor suppressor genes may be involved in the pathogensis of gastric cancer, and the p53 damage may precede an abolished DCC function. On the whole, these data suggest a different chronology for the accumulation of p53 and DCC genetic defects in comparison with colorectal cancer.

The present investigation has strenghts and limitations. Our findings may contribute to a better knowledge of genetic events underlying the development of gastric cancer, but given the retrospective nature of the study, results need confirmation in further series. Also, future investigations should consider the possibility of germline mutations of these tumor suppressor genes, and consequently, the identification of families with affected members and healthy carriers who may be at risk for gastric cancer development.

References

Marshall CJ: Tumor suppressor genes. Cell. 1991, 64: 313-326.

Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC: p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991, 253: 49-53.

Uchino S, Noguchi M, Ochiai A, Saito T, Kobayashi M, Hirohashi S: p53 mutation in gastric cancer: a genetic model for carcinogenesis is common to gastric and colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1993, 54: 759-764.

Craanen ME, Blok P, Dekker W, Offerhaus GJ, Tytgat GN: Chronology of p53 protein accumulation in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut. 1995, 36: 848-852.

Turley H, Pezzella F, Kocilkowski S, Comley M, Kaklamanis L, Fawcett J, Simmons D, Harris AL, Gatter KC: The distribution of the Deleted in Colon Cancer (DCC) proteinh in huma tissue. Cancer Res. 1995, 55: 5628-5631.

Uchino S, Tsuda H, Noguchi M, Yokota J, Terada M, Saito T, Kobayashi M, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S: Frequent loss of heterozygosity at the DCC locus in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1992, 52: 3099-3102.

Fang DC, Jass JR, Wang DX: Loss of heterozygosity and loss of expression of the DCC gene in gastric cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1998, 51: 593-596.

Wu MS, Shun CT, Wang HP, Sheu JC, Lee WJ, Wang TH, Lin JT: Genetic alterations in gastric cancer: relation to histological subtypes, tumor stage, and helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 1997, 112: 1457-1466.

Kataoka M, Okabayashi T, Orita K: Decreased expression of DCC mRNA in gastric and colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 1995, 25: 1001-1007.

Yoshida Y, Itoh F, Endo T, Hinoda Y, Imai K: Decreased DCC mRNA expression in human gastric cancers is clinicopathologically significant. Int J Cancer. 1998, 79: 634-639. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981218)79:6<634::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-0.

Kataoka M, Okabayashi T, Johira H, Nakatani S, Nakashima A, Takeda A, Nishizaki M, Orita K, Tanaka N: Aberrations of p53 and DCC in gastric and colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2000, 7: 99-103.

Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Hermiston ML, Tighe RV, Steen RG, Small CG, Stoeckli ET, Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Rayburn H, et al: Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dec) gene. Nature. 1997, 386: 796-804. 10.1038/386796a0.

Chen YQ, Hsieh JT, Yao F, Fang B, Pong RC, Cipriano SC, Krepulat F: Induction of apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest by DCC. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 2747-2754. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202629.

Mehlen P, Rabizadeh S, Snipas SJ, Assa-Munt N, Salvesen GS, Bredesen DE: The DCC gene product induces apoptosis by a mechanism requiring receptor proteolysis. Nature. 1998, 395: 801-804. 10.1038/27441.

Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H: Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immuoperoxidase techniques. A comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981, 29: 577-580.

Shibata D, Reale MA, Lavin P, Silverman M, Fearon ER, Steele G, Jessup JM, Loda M, Summerhayes IC: The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996, 335: 1727-1732. 10.1056/NEJM199612053352303.

Zhang ZF, Karpeh MS, Lauwers GY, Marrero AM, Pollack D, Cordon-Cardo C, Begg CB: A case-series study of p53 nuclear overexpression in early-stage stomach cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995, 768: 269-271.

Froggatt NJ, Leveson SH, Garner RC: Low frequency and late occurrence of p53 and dec aberrations in colorectal tumours. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1995, 121: 7-15.

Brito MJ, Williams GT, Thompson H, Filipe MI: Expression of p53 in early (T1) gastric carcinoma and precancerous adjacent mucosa. Gut. 1994, 35: 1697-1700.

Kim JH, Uhm HD, Gong SJ, Shin DH, Choi JH, Lee HR, Noh SH, Kim BS, Cho JY, Rha SY, et al: Relationship between p53 overexpression and gastric cancer progression. Oncology. 1997, 54: 166-170.

Starzynska T, Markiewski M, Domagala W, Marlicz K, Mietkiewski J, Roberts SA, Stem PL: The clinical significance of p53 accumulation in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1996, 77: 2005-2012. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<2005::AID-CNCR7>3.0.CO;2-P.

Kakeji Y, Korenaga D, Tsujitani S, Baba H, Anai H, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K: Gastric cancer with p53 overexpression has high potential for metastasising to lymphnodes. Br J Cancer. 1993, 67: 589-593.

Oiwa H, Maehara Y, Ohno S, Sakaguchi Y, Ichiyoshi Y, Sugimachi K: Growth pattern and p53 overexpression in patients with early gastric cancer. Cancer. 1995, 15: 1454-1479.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-2407-1-9-b1.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Graziano, F., Cascinu, S., Staccioli, M.P. et al. Potential role and chronology of abnormal expression of the Deleted in Colon Cancer (DCC) and the p53 proteins in the development of gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 1, 9 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-1-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-1-9