Abstract

Background

Emergency obstetric and neonatal care (EmONC) is a high impact priority intervention highly recommended for improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes. In 2008, Ethiopia conducted a national EmONC survey that revealed implementation gaps, mainly due to resource constraints and poor competence among providers. As part of an ongoing project, this paper examined progress in the implementation of the basic EmONC (BEmONC) in Addis Ababa and compared with the 2008 survey.

Methods

A facility based intervention project was conducted in 10 randomly selected public health centers (HCs) in Addis Ababa and baseline data collected on BEmONC status from January to March 2013. Retrospective routine record reviews and facility observations were done in 29 HCs in 2008 and in10 HCs in 2013. Twenty-five providers in 2008 and 24 in 2013 participated in BEmONC knowledge and skills assessment. All the data were collected using standard tools. Descriptive statistics and t-tests were used.

Results

In 2013, all the surveyed HCs had continuous water supply, reliable access to telephone, logbooks & phartograph. Fifty precent of the HCs in 2013 and 34% in 2008 had access to 24 hours ambulance services. The ratio of midwives to 100 expected births were 0.26 in 2008 and 10.3 in 2013. In 2008, 67% of the HCs had a formal fee waiver system while all the surveyed HCs had it in 2013. HCs reporting a consistent supply of uterotonic drugs were 85% in 2008 and 100% in 2013. The majority of the providers who participated in both surveys reported to have insufficient knowledge in diagnosing postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) and birth asphyxia as well as poor skills in neonatal resuscitation. Comparing with the 2008 survey, no significant improvements were observed in providers’ knowledge and competence in 2013 on PPH management and essential newborn care (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

There are advances in infrastructure, medical supplies and personnel for EmONC provision, yet poor providers’ competences have persisted contributing to the quality gaps on BEmONC in Addis Ababa. Considering short-term in-service trainings using novel approaches for ensuring desired competences for large number of providers in short time period is imperative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (EmONC) is a cost effective priority intervention to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in poor resource settings [1, 2]. Basic EmONC (BEmONC) alone can avert 40% of intrapartum related neonatal deaths and a significant proportion of maternal mortality [3]. Although EmONC initiatives have been implemented in Ethiopia since 1998 [4], the services were not widely available and were inaccessible to the women who needed the services according to a national EmONC survey conducted in 2008 [5]. All the regions are characterized by poor availability and accessibility of the EmONC services, but Addis Ababa and Harere. Weak infrastructure and resource limitations coupled with terrine geography and sparse distributions of rural communities are implicated for the poor availability and accessibility of EmONC in the regions.

In contrast, Addis Ababa has fulfilled the WHO minimum standard in terms of availability and accessibility of the EmONC services yet the quality of the services remains highly compromised. In 2008 there were 29 Health Centres (HCs) providing BEmONC services in Addis Ababa. However, none of these HCs were fully functional, as they had not performed one or more signal function in the three months preceding the survey [5]. Complying with recommendations from the 2008 national EmONC assessment, efforts have been made by local and international stakeholders to improve the quality of EmONC services and to reduce the burden of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

A hospital based national survey in 2010 that analysed constraints from policy to practice in selected emergency obstetric and neonatal conditions in 18 hospitals identified providers poor competence as a major deterrent for ensuring quality comprehensive EmONC [6]. In the case of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) for instance, all the hospitals had policy for PPH management, 92% had the required health personnel, 96% had the necessary supplies and 64% received supervision; yet only 39% of the providers in these hospitals had good knowledge on PPH and only 29% had the skills to properly manage PPH. The same was true for essential newborn care whereby all the hospitals had the policy, 92% had the required health personnel, 70% had the necessary supplies and 64% received supervision; however only 55% of the providers had sufficient knowledge with only 18% providing the care.

Acknowledging the persistence of poor competency among obstetric and newborn health care providers, in 2010 the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) in partnership with local and international stakeholders developed standard BEmONC curricula for in service training [7]. The curricula is a comprehensive document covering a wide range of topics complemented with up-to-date training approaches and gives due emphasis on high impact priority interventions for maximum health gains. Hence, there is a need to revisit the implementation of the BEmONC initiative in Addis Ababa and the progresses made. Making comparisons between the current EmONC status and the 2008 are also important to identify and to respond to the remaining challenges. Findings informed a collaborative project between the University of Bergen, the Addis Ababa City Council Health Bureau and the Addis Ababa University to improve the quality of BEmONC in Addis Ababa. The project uses a before-after design to document changes in maternal and neonatal outcomes. In this paper, we present the baseline data on the BEmONC status of the 10 project HCs in 2013. The paper gives special focus on PPH and neonatal care as these two conditions are well described in the 2008 EmONC survey, which would facilitate comparison between the two surveys and help to document progresses made since 2008.

Methods

Study settings

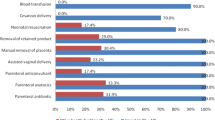

Currently, over 70 public HCs and 4 public hospitals under the Addis Ababa City Administration, Health Bureau provide maternal and child health services to about 80% of the population while the private health facilities share is only about 20% of the care. BEmONC services are provided in the public HCs and hospitals provide comprehensive EmONC. Seven signal EmONC functions are provided at the BEmONC facilities which include parenteral antibiotic, parenteral uterotonic, parenteral anti-convalescent, assisted vaginal delivery, manual removal of placenta, removal of retained product and newborn resuscitation [8]. In addition to the seven signal functions, blood transfusion and caesarean section are provided in comprehensive EmONC facilities. There is a referral network system between HCs and hospitals for mothers and newborn babies requiring advanced interventions. Providers who are referring the mothers or newborn babies arrange ambulance services. The median distance from referring HC to the nearest hospital with surgical service was five about km in 2008 and is expected to be less as the number of HCs has doubled by 2013. All the 10 HCs surveyed in our project in 2013 were also surveyed during the 2008 national EmONC assessment.

Study design, sampling and data collection

A health facility based intervention project has been implemented to improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes in Addis Ababa. The interventions include 1) intensive hands on skills training using simulation technology, 2) developing diagnostic and management protocol for pre-mature rupture of membranes (PROM) occurring at term and 3) implementing the PROM protocol. Ten public HCs were randomly selected, one from each sub-city. These were Woreda 7 HC from Addis Ketema sub-city, Saris HC from AkakiKality, Kebena HC from Arada, Bole 17 HC from Bole, Shiromeda HC from Gulele, Tekelehymanot HC from Lideta, Meshualekiya HC from Kirkos, Woreda 9 HC from KolfeKeraniyo, Woreda 9 HC from Nifas Silk Lafto and Entoto 1 HC from Yeka sub-city.

Data collection methods include retrospective review of routine records, interviews with providers and facility observations. The principal investigator collected all the data between January and March 2013. Trained professionals did the data collection in 2008 from 29 HCs in Addis Ababa. Standard data collection tools, which were adapted to the Ethiopian context during the 2008 national EmONC survey was used in our survey in 2013 [5]. Four major areas were assessed: 1) identification of facility and infrastructure, using observation and interviewing a person of some authority at the facility 2) human recourses, using interview with one knowledgeable person about the staffing pattern and staffing situation 24 hours/7 days a week in the facility 3) essential drugs, equipment and supplies for the provision of EmONC using observation and interviewing a person of some authority at the facility 4) providers knowledge and competency for maternal and newborn care; 24 providers in 2013 and 25 in 2008 were interviewed to assess their knowledge in diagnosing and managing normal labour, PPH and neonatal conditions. Providers were also asked if they ever received EmONC training. In both surveys, the interviewed providers were selected on the basis of their presence on the date the HCs were visited with random selection in 2013 and those who attended the largest number of deliveries in the 2008 survey.

Five questions on obstetrics and five on neonatal care were asked. For assessing knowledge, under each question a list of correct choices were given and providers were asked to give multiple answers (Table 1). Observation of actual performance when care is provided is the standard method for assessing skills. However, this method was not used in the 2008 survey. To facilitate fair comparison between the two surveys we used the same methodologies that were used in 2008. Hence, the proxy skill assessment method used in both surveys was asking providers what they would do to manage an asphyxiated baby for instance. Another method used to assess skill was asking providers what immediate newborn care they provided the last time they attended birth. In both cases interviewees were asked open-ended questions and were not prompted on specific practices.

Percentage, mean scores and fisher exact chi square tests were used for data analyses. We also used independent samples t-tests for comparing knowledge and skills mean scores between the 2008 and 2013 surveys.

The project has received ethical approval from the Addis Ababa City Administration Health Bureau, Ethiopia and the Regional Ethics Committee in Western Norway. Study permits were sought from the Addis Ababa City Administration Health Bureau, the Health Bureaus’ of the respective sub-cities and from all the project health centers. Written informed consent were obtained from the study participants.

Results

Infrastructure

Hundred percent of the surveyed HCs had continuous water and electric supplies and delivery logbooks in 2013 and in 2008. By 2013, 100% of the HCs were having reliable access to telephone and partograph while these figures were 24% and 44% respectively in 2008. Ambulance services were available in 50% of the HCs in 2013 while the remaining HCs were relaying on ambulances from the fire department (command post) especially off working hours. In 2008, only 34% HCs reported to have access to ambulance services (Table 2).

In 2013, all the HCs had a formal fee waiver system and were providing maternal and newborn care free of charge while in 2008, 67% had a formal system to waiver maternal and newborn care.

Essential medicines and supplies

In 2013, all the HCs had reliable supply (no reporting of recent stock outs) of uterotonic drugs, antibiotic eye ointment and intravenous fluids while 50% had parenteral antibiotics and parenteral anticonvulsant (Valium). In the 2008 survey, 85% of the HCs had a reliable supply of uterotonic drugs and 65% had Valium. None of the HCs had Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4) both in 2013 and 2008. Ninety percent and 76% of the HCs had a functional vacuum extractor in 2013 (Table 3) and 2008 respectively (data not shown).

Manpower and caseload

In 2013, there were 72 full time providers working in the labour ward in the 10 HCs with a staffing level of minimum 5 and a maximum 12. The midwives outnumber the nurses (52 vs 20). There were a total of 72 obstetric beds and 22 delivery couches and the total number of deliveries attended in the 10 HCs in the month preceding the survey was 505, which ranged from 18 to 122. In 2013, the ratio of providers for 100 deliveries was 10.3 for midwives and 14.2 for a skilled birth attendant (midwives plus nurses) (Table 4). In 2008, this ratio was 0.26 for midwives and 2.88 for skilled birth attendant (data not shown).

Providers’ knowledge and competence

Of the 24 interviewed providers who were working in the labour ward of the 10 HCs, 21 were midwives and three were nurses. They were between 22 and 36 year of age (mean age 28 years) having five months to 19 years of work experience. Three of the 24 interviewed providers in 2013 and four of the 25 interviewed providers in 2008 reported that they had ever received in-service EmOC training. All the interviewed providers acknowledged that PPH management and neonatal resuscitation are covered in their pre-service curricula. All the 24 providers in 2013 reported that they were routinely using partographs for monitoring and recording labour progress and 44% providers in 2008 reported using partograph.

Table 5 shows providers mean knowledge scores in selected obstetric conditions. In general, providers reported insufficient knowledge both in 2013 and in 2008. Providers who reported to have ever received EmONC training did not demonstrating better knowledge compared to those who never received the training. In 2013, four participants reported that they did not know about Active Management of Third Stage Labour (AMTSL) at all. When we compared the mean knowledge scores of providers on selected obstetric procedures between the 2013 and 2008 surveys, no significant differences were observed (Table 5).

In 2013, providers mean score on diagnosing birth asphyxia was 2.4 out of 4 correct answers. Five providers only knew four of the six preliminary steps of neonatal resuscitation. The mean skill score on how to resuscitate a neonate with bag mask was 1.5 out of 5 correct answers. Comparison of the mean competence score on essential newborn care between the 2013 and 2008 surveys showed no significant difference (p >0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

The study has shown that the majority of the health centres in 2013 had the necessary inputs and personnel for the provision of BEmONC which presents a major improvement in the part of the HCs compared with the 2008 EmONC survey [5]. These reflect the efforts made by the government and other stakeholders to bridge quality gaps on BEmONC in Addis Ababa. However, the lack of progresses between 2008 and 2013 in provider’s competence in detecting, preventing and managing emergency obstetric and neonatal complications entails further concerted efforts.

PPH remains a major cause of maternal mortality and morbidity in poor resource settings [8, 9]. In the absence of proper and prompt management, PPH could claim the life of the women within two hours [8]. Our study showed poor provider’s competence on preventing and managing PPH with no progress over the past years. This is consistent with a study in 18 hospitals in Ethiopia, where only 39% of the providers have knowledge to prevent PPH by 2010 [6]. The persistence of poor providers’ competence could be attributed to gaps in pre-service curricula, lack of continuing education, staff turnover, frequent rotation and limited in-service training in Addis Ababa. A multi country study that included Ethiopia and a study from Nigeria report that the pre-service curricula for midwives and nurses have limitations to ensure graduates with essential midwifery competences up to the standard set by the International Confederation of Midwives [10, 11].

Only 12% of the interviewed providers in 2013 and 16% in 2008 reported receiving in-service BEmONC training. The national Health Sector Development Programme for the year 2010 to 2015 has given focus on developing critical work force skills for improving the quality of health care in Ethiopia with due emphasis on standard in-service trainings [12]. In view of that, a UNICEF funded project run by Jhpiego in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) provided standard BEmONC training for 2007 providers across the country expect Addis Ababa. This would suggest that there is little strategic focus in Addis Ababa to scale up in-service BEmONC training, which requires prompt attention [13].

Atonic PPH is the commonest cause of PPH and is showing an increasing trend [8, 14, 15]. Active Management of Third Stage Labour (AMTSL) is an effective intervention for preventing and managing atonic PPH [8, 16, 17]. AMTSL has three steps; the first step is the administration of oxytocin within 1–2 minutes of birth; the second step is controlled contraction and the third step is uterine massage. Oxytocin is an essential drug for AMTSL whereby all the HCs in 2013 and 85% in 2008 reported having a reliable supply. However, providers’ knowledge on AMTSL remained sub-optimal both in the 2008 and 2013 surveys. Competence gaps in AMSTL appear to be commonplace in many resource poor settings, despite the availability of essential supplies of the procedure. Studies from eight countries, including Ethiopia have reported that AMTSL use is ranging from 0.5% to 32% [6, 18].

Neonatal asphyxia occurs when there is failure to initiate spontaneous breathing whereby about 10% of newborn babies could have this problem at birth [19]. Hence, competence on neonatal resuscitation is critical to help babies who failed to initiate spontaneous breathing at birth or those who breathe poorly [19, 20]. Our study revealed that providers have limited knowledge and skill in identifying and managing neonatal asphyxia and no improvements have seen in 2013 compared to 2008. Consistent with our findings, in a nationwide survey only 55% of professional providing intrapartum care in hospitals have had sufficient knowledge on essential newborn care with only 18% having ever resuscitated a newborn infant [6]. Babies born asphyxiated should be ventilated within the first minute after birth also called “The Golden Minute” and delays to initiate ventilation increase the risk of mortality and long term neurological sequel [19–21].

In Addis Ababa although about 85% of the births are said to be taking place in the health facilities, by 2012 there were 30 stillbirths for 1000 births [22, 23]. Several studies have documented high correlation between facility births and better maternal and perinatal outcomes, yet the situation in Addis Ababa appears to defy this notion [24]. In a study by Harvey and colleagues; many maternal and newborn care providers are not skilled enough; hence giving birth at a health care facility does not guarantee skilled birth care, which seem to be the case in Addis Ababa [25, 26]. Moreover, some of the intrapartum stillbirths could be attributed to diagnostic bias where babies born with primary apnoea would have been misclassified as stillbirths [20]. Although, Ethiopia has achieved MDG 4, two years ahead of time the neonatal mortality and the rate of stillbirth remains high suggesting the need for quality improvement in maternal and newborn care services with, a focus on in-service EmONC training [27].

Several studies have shown that in-service training on essential newborn care and neonatal resuscitation significantly reduces perinatal mortality [3, 21, 28]. In 2010, the FMOH in partnership with other stakeholders developed standard national BEmONC training curricula [7]. The standard BEmONC curricula cover a wide range of obstetric and newborn care topics to ensure providers with the necessary competences. The training is conducted in special set up for three weeks and currently being scaled up across the country. The training curricula incorporated up-to-date interventions, including Helping Mothers Survive (HMS) and Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) modules that use low cost and low-tech simulators proved effective and efficient for ensuring providers competences [21, 28]. The HMS module uses MamaNatalie for simulating prevention and management of PPH while the HBB module uses NeoNatalie for simulating neonatal resuscitation training and these trainings take one day for each module.

Standardising the BEmONC training is a commendable initiative, yet reaching to the great majority of providers with the training could be a daunting costly endeavour particularly for local stakeholders (such as health bureaus and health facilities) as they often have meagre resources. Hence, tailored in-service trainings to address conditions responsible for the deaths of most women and newborn babies would enhance responses. Short course in-service trainings such as the “one-day in-service HMS training for the management of PPH” and the “one day HBB training for neonatal resuscitation” which demonstrate substantial returns in reducing maternal and early neonatal mortality respectively [21, 28], could also be effective and efficient for Ethiopia to ensure providers competence in a short time period with limited budget.

The sample size would have been the main limitation of this report as the study assessed only 10 health facilities in Addis Ababa and included few providers. However, since the facilities were selected randomly and covered over one third of the HCs included in the 2008 EmONC survey, we believe that sample size and selection bias would be insignificant. Selecting the HCs randomly from each sub-city has improved representation, as all HCs under a sub-city would have similarity in infrastructure, logistics, in-service training and supervision. In this study, we used standard data collection tools and checklists adapted to the Ethiopian context to make a fair comparison with the 2008 national EmONC survey. Another limitation is that skills were assessed based on self-report not observed of what providers actually do during deliveries.

Conclusions

Even though commendable progresses have been made in availing the necessary inputs and personnel, sub-optimal quality BEmONC services continues to prevail in Addis Ababa mainly due to poor providers’ competency, which should be a matter of urgent consideration. Although the standard national BEmONC curricula are comprehensive and up-to-date it appears to be not feasible for local partners such as health bureaus and health facilities to implement it. To further bridge the quality gaps in BEmONC, responsible stakeholders might need to consider tailoring competence based in-service short courses on priority maternal and neonatal conditions.

Authors’ information

AHM is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bergen, Norway mainly working on health systems for maternal health, new born health and on the Prevention of mothers to child HIV transmission. MMS is working on behavioural health sciences at the School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. ATR is MNCH team leader at JhPiego, Ethiopia. MMB is working for WAHA international and affiliated to the University of Gondar, Ethiopia.

Abbreviations

- AMTSL:

-

Active Management of Third Stage Labour

- BEmONC:

-

Basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care

- EmONC:

-

Emergency obstetric and neonatal care

- HC:

-

Health center

- FMOH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- MDG:

-

Millennium development goal

- PPH:

-

Postpartum haemorrhage

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, Bhutta ZA, Fogstad H, Mathai M, Zupan J, Darmstadt GL: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ. 2005, 331 (7525): 1107-10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1107.

Accorsi S, Bilal NK, Farese P, Racalbuto V: Countdown to 2015: comparing progress towards the achievement of the health Millennium Development Goals in Ethiopia and other sub-Saharan African countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 104 (5): 336-342. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.12.009.

Lee AC, Cousens S, Darmstadt GL, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, Moran NF, Hofmeyr GJ, Haws RA, Bhutta SZ, Lawn JE: Care during labor and birth for the prevention of intrapartum-related neonatal deaths: a systematic review and Delphi estimation of mortality effect. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11 (Suppl 3): S10-10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S10.

Mekbib T, Kassaye E, Getachew A, Tadessec T, Debebe A: Averting maternal death and disability, The FIGO Save the Mothers Initiative:the Ethiopia–Sweden collaboration. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003, 81: 93-102. 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00071-7.

Admasu K, Haile-Mariam A, Bailey P: Indicators for availability, utilization, and quality of emergency obstetric care in Ethiopia, 2008. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011, 115 (1): 101-105. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.07.010.

Getachew A, Ricca J, Cantor D, Rawlins B, Rosen H, Tekleberhan A, Bartlett L, Hannah G: Quality of Care for Prevention and Management of Common Maternal and Newborn Complications: A Study of Ethiopia’s Hospitals. 2011, Maryland: Jhpiego

FMOH: Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC), Facilitator’s Handbook. 2010, Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health

WHO: WHO Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage and Retained Placenta. 2009, Geneva

Prata N, Bell S, Weidert K: Prevention of postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings: current perspectives. Int J Women’s Health. 2013, 5: 737-752.

Fullerton JT, Johnson PG, Thompson JB, Vivio D: Quality considerations in midwifery pre-service education: exemplars from Africa. Midwifery. 2011, 27 (3): 308-315. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.10.011.

Adegoke AA, Mani S, Abubakar A, van den Broek N: Capacity building of skilled birth attendants: a review of pre-service education curricula. Midwifery. 2013, 29 (7): e64-e72. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.08.009.

FMOH: Health Sector Development Programme IV (HSDP IV). 2010, Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health

Jhpiego: Jhpiego trains over 2,000 health care providers in emergency child birth, establishes 15 training sites. Edited by: News GS. 2013, Addis Ababa

Mehrabadi A, Hutcheon JA, Lee L, Kramer MS, Liston RM, Joseph KS: Epidemiological investigation of a temporal increase in atonic postpartum haemorrhage: a population-based retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2013, 120 (7): 853-862. 10.1111/1471-0528.12149.

Lutomski JE, Byrne BM, Devane D, Greene RA: Increasing trends in atonic postpartum haemorrhage in Ireland: an 11-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2012, 119 (3): 306-314. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03198.x.

Leduc D, Senikas V, Lalonde AB, Ballerman C, Biringer A, Delaney M, Duperron L, Girard I, Jones D, Lee LS, Shepherd D, Wilson K, Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee Society of Obstetricians Gynaecologists of Canada: Active management of the third stage of labour: prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009, 31 (10): 980-993.

Vaid A, Dadhwal V, Mittal S, Deka D, Misra R, Sharma JB, Vimla N: A randomized controlled trial of prophylactic sublingual misoprostol versus intramuscular methyl-ergometrine versus intramuscular 15-methyl PGF2alpha in active management of third stage of labor. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009, 280 (6): 893-897. 10.1007/s00404-009-1019-y.

Stanton C, Armbruster D, Knight R, Ariawan I, Gbangbade S, Getachew A, Portillo JA, Jarquin D, Marin F, Mfinanga S, Vallecillo J, Johnson H, Sintasath D: Use of active management of the third stage of labour in seven developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2009, 87 (3): 207-215. 10.2471/BLT.08.052597.

Perlman J, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins D, Chameides L, Goldsmith J, Guinsburg R, Hazinski M, Morley C, Richmond S, Simon WM, Singhal N, Szyld E, Tamura M, Velaphi S, Neonatal Resuscitation Chapter Collaborators: Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Pediatrics. 2010, 126 (5): e1319-e1344. 10.1542/peds.2010-2972B.

Ersdal H, Singhal N: Resuscitation in resource-limited settings. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 18 (6): 373-378. 10.1016/j.siny.2013.07.001.

Msemo G, Massawe A, Mmbando D, Rusibamayila N, Manji K, Kidanto HL, Mwizamuholya D, Ringia P, Ersdal HL, Perlman J: Newborn mortality and fresh stillbirth rates in Tanzania after helping babies breathe training. Pediatrics. 2013, 131 (2): e353-e360. 10.1542/peds.2012-1795.

Central Statistical Agency, ICF International: Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012, Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency

FMOH: Health and Health Related Indicators. 2012, Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health

Yakoob M, Ali M, Ali M, Imdad A, Lawn J, Van Den Broek N, Bhutta Z: The effect of providing skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care in preventing stillbirths. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11 (Suppl 3): S7-10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S7.

Knight HE, Self A, Kennedy SH: Why are women dying when they reach hospital on time? A systematic review of the ‘third delay’. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (5): e63846-10.1371/journal.pone.0063846.

Harvey S, Blandon Y, McCaw-Binns A, Sandino I, Urbina L, Rodriguez C, Gomez I, Ayabaca P, Djibrina S: Are skilled birth attendants really skilled? A measurement method, some disturbing results and a potential way forward. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85 (10): 783-790. 10.2471/BLT.06.038455.

UNICEF: Levels in Trends in Child Mortality; Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. 2013, Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF

Goudar SS, Somannavar MS, Clark R, Lockyer JM, Revankar AP, Fidler HM, Sloan NL, Niermeyer S, Keenan WJ, Singhal N: Stillbirth and newborn mortality in India after helping babies breathe training. Pediatrics. 2013, 131 (2): e344-e352. 10.1542/peds.2012-2112.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/354/prepub

Acknowledgement

The study was financially supported by the Center for International Health, university of Bergen. We thank the Addis Ababa City Administration Health Bureau for providing study permit and venue for sensitization workshops. All the ten sub-cities and the study HCs deserve thanks for providing us study permits. We are grateful for the midwives who participated in the interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AHM prepared the proposal, collected and analysed the data, interpret the findings and wrote the manuscript. MMS, ATR and MMB were involved in developing the proposal and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirkuzie, A.H., Sisay, M.M., Reta, A.T. et al. Current evidence on basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 354 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-354

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-354