Abstract

Background

Each year almost 3 million newborns die within the first 28 days of life, 2.6 million babies are stillborn, and 287,000 women die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth worldwide. Effective and cost-effective interventions and behaviours for mothers and newborns exist, but their coverage remains inadequate in low- and middle-income countries, where the vast majority of deaths occur. Cost-effective strategies are needed to increase the coverage of life-saving maternal and newborn interventions and behaviours in resource-constrained settings.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken on the cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve the demand and supply of maternal and newborn health care in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Peer-reviewed and grey literature published since 1990 was searched using bibliographic databases, websites of selected organizations, and reference lists of relevant studies and reviews. Publications were eligible for inclusion if they report on a behavioural or health systems strategy that sought to improve the utilization or provision of care during pregnancy, childbirth or the neonatal period; report on its cost-effectiveness; and were set in one or more low-income or lower-middle-income countries. The quality of the publications was assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement. Incremental cost per life-year saved and per disability-adjusted life-year averted were compared to gross domestic product per capita.

Results

Forty-eight publications were identified, which reported on 43 separate studies. Sixteen were judged to be of high quality. Common themes were identified and the strategies were presented in relation to the continuum of care and the level of the health system. There was reasonably strong evidence for the cost-effectiveness of the use of women’s groups, home-based newborn care using community health workers and traditional birth attendants, adding services to routine antenatal care, a facility-based quality improvement initiative to enhance compliance with care standards, and the promotion of breastfeeding in maternity hospitals. Other strategies reported cost-effectiveness measures that had limited comparability.

Conclusion

Demand and supply-side strategies to improve maternal and newborn health care can be cost-effective, though the evidence is limited by the paucity of high quality studies and the use of disparate cost-effectiveness measures.

Trial registration

PROSPERO_CRD42012003255.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, each year 3 million newborns die within the first 28 days of life [1], 2.6 million babies are stillborn [2], and 287,000 women die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth [3]. The vast majority of these deaths occur in Africa and Asia, many could be prevented by improving access to existing interventions [1–3]. Substantial evidence exists on a wide range of interventions and behaviours, and reviews have identified life-saving maternal and newborn health (MNH) interventions that are not only effective, but also cost-effective and suitable for implementation in resource-constrained settings [4–6]. Examples include iron supplements to prevent anaemia, tetanus toxoid immunization, magnesium sulphate for eclampsia, uterotronics to prevent and manage post-partum haemorrhage, hygienic cord care, immediate thermal care, exclusive breastfeeding, and management of neonatal sepsis, meningitis and pneumonia [6]. It has been estimated that increased coverage and quality of pre-conception, antenatal, intra-partum, and post-natal interventions by 2025 could avert 71% of newborn deaths [5].

Despite efforts to identify priority interventions, access to life-saving MNH interventions remains inadequate in low and middle income countries [6]. There may be delays making the decision to seek care, difficulties in reaching care, or problems with the range or quality of care available [7]. To achieve higher coverage of MNH interventions, effective and cost-effective strategies need to be identified that address these challenges and lead to improvements in the utilization and provision of MNH care. Demand-side strategies are needed to influence health practices of individuals and communities and promote uptake of preventive and curative MNH care during pregnancy, childbirth and in the post-natal period. These strategies may provide health information and education, or address geographic, financial, or cultural barriers to accessing care. At the same time, supply-side strategies are needed to enhance the capability and performance of front-line health workers, who as the first point-of-contact for women and newborns provide essential care in the community and at primary health facilities. Supply-side strategies may involve training to ensure health workers have the necessary knowledge and skills, and strategies to motivate health workers, improve the working environment and resources available, or strengthen other aspects of the health system.

Several recent reviews have summarized the evidence on the effectiveness of these strategies to improve MNH care in low and middle income countries [8–14]. The reviews range in scope and setting, and have focused on community-based strategies, integrated primary care, and urban settings. However, given resource constraints, it is important to know not only what strategies are effective at improving coverage of MNH interventions, but also whether the strategies are cost-effective. This has been highlighted as a research priority [12], and the existing reviews contain only limited information on cost-effectiveness [9, 11, 12, 14].

This paper presents a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve the demand and supply of maternal and newborn health care in low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Our focus is not the interventions and behaviours themselves, but strategies for ensuring they are made available and taken up. The protocol for the systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) [15].

Methods

Searches

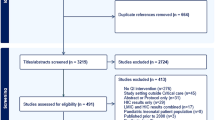

The title and abstract of peer-reviewed and grey literature published since 1 January 1990 were searched using terms (including synonyms and MeSH terms) for three concepts: i) cost-effectiveness, ii) MNH care, and iii) LICs and LMICs (Additional files 1 and 2). Searches were conducted in six electronic bibliographic databases, Medline, Embase, Global Health, EconLit, Web of Science, and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Additional file 1) on 14 September 2012 and last updated on 16 October 2013. Grey literature was searched using the Popline database and websites of selected organizations and networks, including the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Maternal Health Task Force, Healthy Newborn Network, UNICEF, and World Health Organization (Additional file 1). This initial search identified 3236 non-duplicate publications that were eligible for title and abstract screening (Figure 1). The reference lists of reviews identified in the title and abstract search and included publications were also screened.

Article selection and exclusion criteria

The process of study selection is summarized in Figure 1. The title and abstract of the retrieved citations were uploaded into EPPI Reviewer 4 software [16] and independently screened by two reviewers (LMJ and CP). Publications that did not clearly meet criteria for exclusion were retained for full text review. The full text of retained publications was then independently assessed for exclusion criteria by both reviewers and any reasons for exclusion recorded. Discrepancies between reviewers were relatively few and were resolved through discussion without the need to consult a third reviewer.

At the title and abstract review stage, publications were excluded if they fulfilled any of the following criteria:

-

Did not report on a strategy that sought to influence health practices or enhance front-line worker performance.

-

Did not report on maternal or newborn care.

-

Was not set in a LIC or LMIC.

-

Did not report on costs.

-

Did not report the effect of the strategy.

-

Was published before 1990.

-

Was a letter or editorial.

At the full-text review stage, publications were excluded if they met any of the previous criteria, or, additionally, if they:

-

Did not report a cost-effectiveness measure.

-

Presented secondary rather than primary analysis (in which case the references were checked for additional articles for inclusion).

The definitions used for “cost-effectiveness measure”, “strategies”, “maternal and newborn health care”, and “LICs and LMICs” are provided in Table 1.

Data extraction

A standardized form was used to extract the data required for the quality assessment and evidence synthesis. The first reviewer (LMJ) completed the data extraction form for all studies, and the second reviewer (CP) assessed the accuracy of the extracted data and quality assessment. Differences were resolved through discussion.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement [17], which was published in 2013. The CHEERS statement contains a checklist of 24 criteria intended to establish the minimum information that should be included when reporting economic evaluations of health strategies and interventions and each publication included in the review was assessed against these criteria.

To obtain an overall quality assessment, publications scored 1 point for each criterion fully met, 0.5 for each partially met and 0 for each when no or very little information was reported. A percentage score was then generated, giving all criteria equal weight (criteria not applicable were excluded from the calculation). Studies that scored 75% or more were categorized as high quality, scores in the range 50-74% were ranked medium, and scores less than 50% were ranked poor. As two of the reporting criteria may depend on the publisher (source of funding and conflicts of interest), we also calculated the percentage score excluding these criteria and found this had no effect on the categorization.

Data synthesis

Descriptive information about the eligible studies was summarized using text and tables. The demand- and supply-side strategies were listed alongside a brief description, its comparator, and whether it focused on a specific aspect of MNH care (Table 2). The study design, study year and primary outcome measure are also listed, and the effect of the strategy is included when a relative risk, odds ratio or proportion by study arm was reported.

Narrative synthesis was used to analyse and interpret the findings. Across the studies common themes were identified, based on the authors’ description of the strategy, whether it was implemented in the community, primary care facilities or hospitals, and whether it was specific to pregnancy, intra-partum, post-partum or post-natal care or applied to multiple stages in the continuum of care [66].

To facilitate synthesis, the cost-effectiveness results were converted to US Dollars (USD) and inflated to 2012 prices [67, 68]. The results are presented with summary information on the quality of the reporting, the costing perspective, and whether the health effects were measured in women or newborns, as these are important considerations for interpretation (Table 3). Meta-analysis was not appropriate given the diversity of strategies and differences in how the studies were framed. The country’s gross domestic product per capita (GDP-PC) (in 2012 prices) was used as a benchmark against which to consider the cost-effectiveness of strategies that reported the cost per life-year saved, cost per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) averted or cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained [69]. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers strategies and interventions to be cost-effective if the cost per DALY averted is less than three times the GDP-PC and highly cost-effective if less than the GDP-PC [70].

Results

The title and abstract of 3236 publications were screened and the full text of 140 publications was reviewed (Figure 1). This included three publications identified from reference lists [19, 37, 47]. One publication identified for full-text review could not be retrieved and so was not reviewed. Ninety-two publications were excluded at full-text review. Fourteen of the excluded publications were literature reviews, whose references were manually searched for relevant studies. One publication was excluded because the study was not in a LIC or LMIC. Sixteen publications were excluded because they assessed medical interventions rather than a strategy, and a further 6 publications were excluded because they focused on health topics, such as immunization or HIV, without specific reference to MNH care. Of those remaining, 8 publications were excluded because the cost-effectiveness of the strategy was not measured in a maternal or newborn population, though we did include one article that reported the cost per infant death averted. The latter reported on the distribution of mosquito nets to pregnant women and was included since the deaths averted would primarily be in newborns. A further 11 publications mentioned cost-effectiveness in the abstract but were excluded because they did not contain any cost data. Finally, 36 publications were excluded because they did not report a measure that combined cost and effect. For instance, several studies reported the total cost or a unit cost of implementing the strategy, such as the cost per health worker trained.

Overview of the studies

Of the 48 publications included in the review, 41 were articles from peer-reviewed journals and 7 were reports from the grey literature. Thirty-six were published since 2000, and 20 were published since 2009. The 48 publications reported on 43 separate studies undertaken in 21 different countries (Figure 2). Twenty-three studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, 17 in Asia, and one each in Honduras, Papua New Guinea and Ukraine. Just over half (n = 23) of the studies were from five countries: Bangladesh (n = 8), India (n = 5), Kenya (n = 4), Uganda (n = 3) and Zambia (n = 3).

Strategies to improve utilization and provision of MNH care

The review identified a wide range of strategies to improve the utilization and provision of MNH care (Table 2). Some strategies focus on improving the coverage of a specific intervention or behaviour, while others cover multiple aspects of MNH care. The majority of the strategies focused on care during pregnancy and many involved community-based strategies, either to stimulate demand for MNH care or complement facility-based services. Although each strategy is distinct, there were some common themes, which we describe below and depict visually by presenting the different strategies in relation to the continuum of care and the different levels of the health system (Figure 3).

Health promotion and health education were central to many of the community-based strategies. Women’s groups were used to improve MNH in five related studies implemented in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Malawi [18, 37, 47, 49, 51]. Each study had a similar strategy, which involved training literate women from the local community to facilitate monthly women’s group meetings and work with participants to identify priority issues and implement local solutions, such as establishing a community-fund, stretcher schemes, and supplying clean delivery kits. Inspired by the use of women’s groups in Nepal, researchers in Cambodia piloted a participatory approach in which midwives held focus group discussions with pregnant women on birth preparedness and danger signs [32]. Community mobilization also featured in other strategies, and local leaders were used to help promote attendance at antenatal care (ANC) [21, 22, 52], syphilis testing [63], facility-births [29], and an immunization campaign [42].

Other strategies focused on removing barriers to care. Three reduced the cost of maternal care: user fees for intra-partum care were removed in Senegal to encourage women to deliver in facility, a nominal fixed charge was introduced for all maternal health services in The Gambia [34, 57] and the third study combined vouchers for pregnant women to access free maternal care, cash to cover transport costs and in-kind items [19]. A further two studies evaluated emergency transport schemes, which had been established to facilitate referral for women with pregnancy or obstetric complications [55, 61].

Various strategies were used to provide or improve MNH care at home and in the community. Several studies evaluated the cost-effectiveness of recruiting and training community health workers and volunteers to undertake home-based care [39–41, 49, 54, 59]. Their role typically involved identifying pregnant women, providing advice on preparing for birth, on danger signs and on breastfeeding, however the extent of their responsibilities varied. In some instances, their role also included distribution of malaria prophylaxis, folic acid and iron supplements to pregnant women [59], or the management of birth asphyxia and treatment of neonatal sepsis [39–41]. Training traditional birth attendants (TBAs) was another strategy to improve community-based MNH care, though only one study was specifically designed to evaluate this [65], as estimates from Bangladesh were based on secondary sources [26].

The provision of family planning and MNH services by facility-based staff in outreach clinics was another theme [23, 25, 34, 52]. Most of these studies compared the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for service delivery. For example, a tetanus toxoid campaign and home-based distribution of malaria prophylaxis were compared to routine antenatal care [42, 59]. Economic models were also used to assess whether HIV screening in pregnancy should be restricted to high prevalence states [38] and to estimate the cost-effectiveness of four variants of abortion care [58].

Strategies to improve and extend facility-based services were also deployed. The strategies were wide-ranging though typically included training, equipment and supplies. Examples include quality improvement initiatives that encouraged health workers to identify and address problems with the care provided in their facility [47, 52], and the Bamako Initiative on primary care, which was evaluated in Benin and Guinea using secondary data on the utilization of antenatal care [27]. Other studies focused on specific aspects of MNH care. Several strategies extended routine antenatal care, by distributing mosquito nets or introducing testing for HIV or syphilis [31, 33, 43–46, 63]. The quality of intra-partum and post-natal care was a specific focus in some studies, both at primary facilities [20, 29, 64] and maternity hospitals [36, 62]. In addition, two studies assessed the cost-effectiveness of training mid-level health workers to provide emergency obstetric care [28, 50]. Finally, there were two studies focusing on specialist elements of MNH care: one on intensive and special neonatal care in Papua New Guinea [56] and the other on the provision of obstetric fistula care in Niger [53].

Study design and evaluation

In the vast majority of studies, the strategy was compared to the situation before or without the strategy, though there were a few examples that compared the provision of MNH care at a facility with care at home, or in a community outreach clinic. Seven studies were conducted in the context of cluster randomized trials (including 2 with a factorial design), 3 were pre-post studies with a control, and 16 studies had a pre-post design without a control group. In addition, 7 studies compared intervention and control areas, 2 used prospective cohort data, 4 used economic modelling, and 4 used secondary data to estimate the cost-effectiveness results.

The effect of the strategies on the utilization and provision of health care and on health outcomes was measured using various indicators. Several studies evaluated the change in maternal or newborn mortality rates. Other studies report the effect on health care interactions or coverage of interventions, such as the percentage of pregnant women having at least three antenatal visits, the proportion of facility births or the number of pregnant women tested for HIV.

Assessment of study quality

Sixteen studies were graded as high, 12 as medium, and 15 as low quality in their reporting (Table 3). Articles that reported cost-effectiveness results alongside other study outcomes tended to omit important methodological information. For example, several studies were not explicit about the costing perspective or the costs included. In comparison, articles that had cost-effectiveness as the primary objective were more comprehensive in their reporting. These articles usually provided detail on the rationale for the cost-effectiveness analysis and methods used, and many reported on sensitivity analyses that had been undertaken to explore uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness ratio. Most of the studies reported the incremental cost-effectiveness of a strategy (either compared to an alternative strategy or doing nothing) though four studies used average cost-effectiveness ratios to compare alternative strategies [23, 25, 42, 50], which can be misleading and hide the true cost of achieving incremental health care goals [71].

There were large differences in the quality and content of the economic evaluations conducted, particularly in the approach and methods used to estimate costs. The majority of studies adopted a health service provider perspective, and relatively few took into account the costs incurred by households to access MNH care. Some studies analysed only recurrent costs, having excluded any initial set-up costs [23, 36, 46, 61], and several analysed the cost of the strategy without taking into account the cost implications of delivering maternal and newborn care [18–21, 32, 37, 39, 41, 47, 49, 51, 54, 55]. For example, use of women’s groups resulted in increases in the uptake of antenatal care in Malawi and Nepal and institutional deliveries in Nepal, but the additional cost of this increase in service utilization was not taken into account [14]. In addition, a couple of studies included only the cost of equipment and supplies [40, 56]. In contrast, a number of studies were more comprehensive and used economic rather than financial costing, which meant market values were included for donated goods and volunteer time [22, 33, 34, 50, 52, 53, 59, 65].

Evidence of cost-effectiveness

A range of measures were used to report the cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve the utilization and provision of MNH care, and many studies reported more than one outcome (Table 3). The most common single measure was the cost per life saved (also known as cost per death averted) and this was used in 16 of the 43 studies. Thirteen of these studies focused on newborns, one on infants [33] and two estimated lives saved in both women and newborns [34]. Seven studies reported the cost per life-year saved (or cost per year of life lost averted) in either women or their newborns [33, 34, 38, 49, 51, 61]. This measure takes into account not only the number of lives saved but also the number of years of life, based on the beneficiary’s age and their expected length of life. There were also nine cost-utility studies, where the effect on health is measured in a composite indicator combining the number of years of life and the quality of life: seven reported the cost per DALY averted [22, 33, 36, 39, 52, 59, 65] and two reported the cost per QALY gained [23, 25]. Twenty studies reported strategy-specific cost-effectiveness measures. Some referred to a specific health effect, such as case of congenital syphilis averted, while others reported on the health care received, using measures such as the cost per insecticide-treated mosquito net (ITN) delivered, cost per facility-birth, or cost per home visit.

In the vast majority of studies, the strategy was found to be more effective but also more costly than its comparator, and therefore the decision on whether to adopt a strategy depends on the decision maker’s willingness to pay for improvements in health or health care. An exception was in Ukraine where efforts to encourage evidence-based policies and reduce the use of Caesarean sections was found to be cost saving. There was also evidence that training mid-level cadres in emergency obstetric care had a lower average cost per life saved than training obstetricians [28]. Using GDP per capita as a benchmark against which to consider the cost per DALY averted, cost per QALY gained and cost per life-year saved, all the strategies that report these measures would be considered cost-effective [70].

Discussion

Our systematic review identified 48 publications on the cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve the utilization and provision of MNH care in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. The 48 publications reported on 43 separate studies and we judged the reporting of 16 of these studies to be of high quality with respect to the CHEERS reporting criteria.

There was considerable diversity in the strategies used to improve MNH care, and also in the setting, intensity and scale of implementation. However, it was possible to identify some common themes among the strategies, and these were presented in relation to the continuum of care and the level of the health system. This synthesis summarized the cost-effectiveness literature available and highlights the extent to which the evidence focuses on community-based strategies and care during pregnancy. It also emphasizes the lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve post-partum care. In addition, it was interesting to note the large proportion of strategies focused on a specific aspect of MNH care. This was particularly noticeable in the facility-based strategies, which included a number of strategies to extend antenatal care and improve specialist care.

It is clear that demand and supply-side strategies can be cost-effective in enhancing the utilization and provision of MNH care and improving health outcomes. Strategies that reported on the cost per life-year saved and cost per DALY averted were cost-effective when compared to GDP per capita. These strategies, in their specific settings, included the use of women’s groups [18, 37, 47, 49, 51]; home-based newborn care using community health workers, volunteers and traditional birth attendants [22, 39, 59, 65]; adding services to routine antenatal care [33]; a facility-based quality improvement initiative to enhance compliance to care standards [52]; and the promotion of breastfeeding in maternity hospitals [36]. However, it should be noted that the results may not be transferable beyond the study setting and using GDP per capita as a threshold does not necessarily ensure that the strategy is affordable. Using GDP per capita as the threshold also approaches cost-effectiveness from a national perspective, and it has been suggested that a global minimum monetary value for a DALY would improve the transparency and efficiency of priority setting for international donors [72].

It is more difficult to interpret the cost-effectiveness results when strategy-specific measures were reported, such as the cost per Caesarean-section, or cost per syphilis case treated. Very few studies use the same measure, though some report estimates from the same setting at different points in time [39, 41, 44–46]. In many of the studies the costs appear low given the potential health benefits, though the results should be interpreted with care as the choice of measure can also affect conclusions. For example, the cost per woman vaccinated with tetanus toxoid was much lower when the vaccination took place in a campaign rather than during routine antenatal care, however, targeting the vaccine to pregnant women attending antenatal care was found to be more cost-effective when the cost per life saved was estimated [42]. This example highlights the benefits of using health outcomes data, and where that is not available, the value in extrapolating beyond intermediate measures to estimate the number of lives saved using models, such as the Lives Saved Tool (LiST) [73]. Strategy-specific measures also have limited use for priority-setting as decision-makers cannot directly compare strategies that report different cost-effectiveness measures.

The extent to which alternative strategies can be compared was also limited by the how the cost-effectiveness analysis was framed. The reported results may depend on the choice of comparator, the costs included and any assumptions about the effect of the strategy on the quantity and quality of life. For instance, a commentary accompanying the article on training assistant medical officers to perform emergency obstetric care argued the cost-effectiveness results may be an under-estimate since ‘doing nothing’ would be a more realistic comparator than training surgeons given the shortage of medical personnel in Mozambique [50]. The costing perspective is another dimension that can affect study results. For instance, from a health services perspective, delivering home-based care was found to be more expensive than providing services in an outreach clinic or at the health facility, but this perspective does not take into account the direct and indirect costs incurred by households to obtain care [25]. The range of costs included can also have a dramatic impact. For example, when interpreting the results of the study on the management of birth asphyxia by health volunteers it is important to acknowledge the estimate of US$25 per life saved only takes into account the cost of the equipment, and does not include the cost of other supplies or value the time donated by health volunteers [40].

We had hoped to learn the extent to which cost-effectiveness depends on the strength or scale of implementation, or country-specific factors, and each of these considerations is salient for the transferability of study results. Intensive implementation may improve the strategy’s effectiveness, but this is likely to come at a cost. Similarly, the scale of implementation may affect costs or effects, and the potential to generate economies of scale will depend on the characteristics of the strategy and the geographic setting. The context for a study can also influence costs and effects, and the degree to which a strategy can be replicated in another setting. One study reported that there would be economies of scale if the women’s group initiative were rolled out in Bangladesh, and another on the Bamako Initiative reported relatively similar cost-effectiveness in Benin and Guinea [18, 27]. However, drawing conclusions across studies is extremely challenging given the wide-ranging strategies implemented in disparate contexts. The women’s group studies were the most comparable since a common strategy was applied in different countries and with differing intensity (in terms of population coverage), and they were methodologically similar as the studies had several researchers in common. Looking across these studies there was some evidence that greater intensity of implementation produced a larger effect, though implementation and contextual factors may impact on the effect sizes [14]. As others have noted, understanding determinants of differences in cost, and the effect of scale on cost are priorities for future work [14].

Only three studies reported a cost-effectiveness measure that took into account the combined effect of the strategy on both maternal and newborn health. One of the distinctive characteristics of pregnancy and intra-partum care is the potential for the care to benefit both the woman and her child. In addition, intervening during pregnancy can affect subsequent care seeking and health outcomes. Thus, the cost-effectiveness of a strategy may be under-estimated if the health benefits were measured in either women or newborns but not both [74], though this point was not highlighted in any of the publications.

In drawing conclusions we need to bear in mind the quality of the publications. The CHEERS checklist sets a standard for the information that should be reported, and although there were some high quality publications, many fell short of the standard. The publications of low and medium quality were often those in which the cost-effectiveness analysis was presented as supplementary to other study results and a strategy-specific measure was used. In some cases, gaps in reporting made it difficult to assess whether methods were appropriate, what assumptions had been made and how the findings should be interpreted. As many peer-reviewed journals have restrictions on article length, authors should make better use of web appendices or, ideally, report the cost-effectiveness analysis as a separate, stand-alone article. Discussion of the cost-effectiveness results was another aspect where the quality was often limited, and conclusions on the cost-effectiveness of the strategy were often stated with only a cursory consideration of study design, context, and limitations, and without reference to the existing literature.

However, the checklist also has some limitations. It focuses on the quality of the reporting rather than the quality of the economic evaluation conducted. This means articles with a clear description of their methods may rank highly even when there are shortcomings in how the study was framed or the range of costs included. In addition, several of the criteria more readily apply to cost-effectiveness analyses that use individual patient-level data or economic modelling, which are the backbone of cost-effectiveness studies in high income countries, but less frequently used in low and middle income countries. We also acknowledge the quality categorization was based on a simple approach and alternative methodologies could be applied, such as assigning weights to the criteria based on subjective judgment or statistical analysis.

We took a systematic approach to the literature search and selection process, though there is always a risk that a relevant article has been missed, and it was not always straightforward to determine whether an article satisfied the inclusion criteria. For example, we carefully considered whether to include article publication that compared universal HIV screening in pregnant women with screening restricted to areas of high HIV prevalence [38]. We also carefully considered the eligibility of several articles that reported costs in relation to a process indicator, such as the study from Cambodia on midwife-led group discussions with pregnant women that reported the cost per educational interaction [32]. We decided that process indicators would be eligible if they referred to an interaction between women (or newborns) and a front-line worker. Publication bias is also a potential concern, since cost-effectiveness analyses are often only undertaken in field-studies once a positive effect has been demonstrated, though the lack of statistically significant effect does not necessarily preclude a strategy from being cost-effective, nor should it prevent a cost-effectiveness analysis being published [75, 76]. That all the studies in our review had positive findings was striking, and suggests that cost-effectiveness analyses with negative findings may not have been published.

The review highlights a need for future research. Only a minority of studies on strategies to improve the utilization and provision of MNH care consider their cost-effectiveness [8–14]. Moreover, the evidence available is limited by the lack of high quality reports presenting comparable cost-effectiveness measures. In particular, there are gaps relating to post-partum and post-natal care, and relatively few studies focused on the quality of intra-partum care. Further work on the extent to which implementation, scale and context impact cost-effectiveness would also be useful to understand the degree to which strategies can be replicated elsewhere. Moreover, for future research to generate results that can be transferred beyond the immediate study setting, greater consideration should be given to how the economic evaluation is framed. This includes the use of a comparable cost-effectiveness measure, such as cost per DALY averted, and also a costing that reflects the full cost to everyone of implementing the strategy within the prevailing health system. It is good practice to take household costs into account and to value donated goods and volunteer time. As the initiative to promote facility-births in Burkina Faso demonstrated, the cost of the strategy (as opposed to the intervention alone) can be substantial: there was an eightfold increase in the cost of a facility birth when programme costs were included in the calculations [29]. Thus, estimates of the cost-effectiveness of life-saving MNH interventions that do not take into account demand or supply strategies will substantially under-estimate the resources required to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality.

Conclusion

Demand and supply-side strategies can be cost-effective in enhancing the utilization and provision of MNH care and improving health outcomes, though the evidence available is limited by the lack of high quality studies using comparable cost-effectiveness measures. Direct comparison of alternative strategies was also limited by how the studies were framed, as there was substantial variation in how researchers approached, designed and analyzed cost-effectiveness. Further studies are needed, though existing evidence shows the cost-effectiveness of several strategies implemented in the community to influence health practices and care seeking, and also facility-based initiatives to improve the range and quality of MNH care available.

Abbreviations

- Adj:

-

Adjusted

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- C:

-

Comparator

- CHEERS:

-

Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- C-section:

-

Caesarean section

- DALY:

-

Disability-adjusted life year

- EmOC:

-

Emergency obstetric care

- Excl:

-

Excluding

- FP:

-

Family planning

- FWA:

-

Family welfare assistant

- GDP-PC:

-

Gross domestic product per capita

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HSS:

-

Health system strengthening

- IMR:

-

Infant mortality rate

- Incl:

-

Including

- ITNs:

-

Insecticide-treated bed nets

- IPTp:

-

Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy

- LB:

-

Live births

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

- LIC:

-

Low-income country

- LiST:

-

Lives Saved Tool

- LMIC:

-

Lower-middle income country

- MCH:

-

Maternal and child health

- MNCH:

-

Maternal, newborn, and child health

- MNH:

-

Maternal and newborn health

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality rate

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organisation

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NMR:

-

Neonatal mortality rate

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PHC:

-

Primary health care

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-year

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- S:

-

Strategy

- S1:

-

Strategy 1

- S2:

-

Strategy 2

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendant

- TT:

-

Tetanus toxoid

- USD:

-

United States Dollars

- VHW:

-

Village health workers

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Oestergaard M, Inoue M, Yoshida S, Mahananai W, Gore F, Cousens S, Lawn J, Mathers C, on behalf of the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation and the Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group: Neonatal Mortality Levels for 193 Countries in 2009 with Trends since 1990: A systematic analysis of progress, projections and priorities. PLoS Med. 2011, 8 (8): e1001080-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001080.

Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, Creanga A, Tuncalp O, Balsara Z, Gupta S, Say L, Lawn JE: National, regional and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9774): 1319-1330. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62310-0.

World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank: Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization

Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, Bhutta ZA, Fogstad H, Mathai M, Zupan J, Darmstadt GL: Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ. 2005, 331: 1107-10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1107.

Bhutta AZ, Das JK, Bahl R, Lawn JE, Salam RA, Paul VK, Sankar JM, Blencowe H, Rizci A, Chou VB, Walker N, For The Lancet Newborn Interventions Review Group and The Lancet Every Newborn Study Group: Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost?. Lancet. 2014, Early online publication: doi:10.1016/S0140-6736 (14) 60792-3

The Partnership for Maternal Newborn and Child Health: A Global Review of the Key Interventions Related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (RMNCH). 2011, Geneva: PMNCH

Thaddeus S, Maine D: Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994, 38 (8): 1091-1110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7.

Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan Babar S, Haws Rachel A: Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005, 115: 519-617.

Bhutta ZA, Ali S, Cousens S, Ali TM, Haider BA, Rizvi A, Okong P, Bhutta SZ, Black RE: Alma-Ata: Rebirth and revision 6 - Interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival: what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make?. Lancet. 2008, 372: 972-989. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61407-5.

Bhutta ZA, Yakoob MY, Lawn JE, Rizvi A, Friberg IK, Weissman E, Buchmann E, Goldenberg RL: Lancet’s Stillbirths S, Steeri: Stillbirths 3 Stillbirths: what difference can we make and at what cost?. Lancet. 2011, 377: 1523-1538. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62269-6.

Coast E, McDaid D, Leone T, Pitchforth E, Matthews Z, Iemmi V, Hirose A, Macrae-Gibson R, Secker J, Jones E: What are the effects of different models of delivery for improving maternal and infant health outcomes for poor people in urban areas in low income and lower middle income countries?. 2012, London: EPPICentre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, Feb; 2012

Murray S, Hunter B, Bisht R, Ensor T, Bick D: Effects of demand-side financing on utilisation, experiences and outcomes of maternity care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014, 17 (1): 30-

Nyamtema A, Urassa D, Van Roosmalen J: Maternal health interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review of packages, impacts and factors for change. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011, 11: 30-10.1186/1471-2393-11-30.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, Houweling Tanja AJ, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, Lewycka S, MacArthur C, Manandhar D, Morrison J, Mwansambo C, Nair N, Nambiar B, Osrin D, Pagel C, Phiri T, Pulkki-Brannstrom AM, Rosato M, Skordis-Worrall J, Saville N, Shah More N, Shrestha B, Tripathy P, Wilson A, Costello A: Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013, 381: 1736-1746. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6.

Mangham-Jefferies L, Pitt C: Cost-effectiveness of innovations to improve the utilization and provision of maternal and newborn health care in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. PROSPERO. 2012, CRD42012003255-

EPPI Centre: Welcome to the EPPI-Reviewer 4 gateway. Vol. Last accessed 13/01/14. 2013, http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?alias=eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4: EPPI Centre

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs A, Mauskopf J, Loder E, and on behalf of the CHEERS Task Force: Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Cost Effectiveness Resour Allocation. 2013, 11: 6-10.1186/1478-7547-11-6.

Fottrell E, Azad K, Kuddus A, Younes L, Shaha S, Nahar T, Aumon B, Hossen M, Beard J, Hossain T, Pulkki-Brannstrom AM, Skordis-Worrall J, Prost A, Costello A, Houweling TAJ: The effect of increased coverage of participatory women’s groups on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh. A cluster randomized trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013, 167 (9): 816-820. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2534.

Hatt L, Ha N, Sloan N, Miner S, Magvanjav O, Sharma A, Chowdhury J, Chowdhury RI, Paul D, Islam M, Wang H: Economic evaluation of demand-side financing for maternal health in Bangladesh. Review, Analysis and Assessment of Issues Related to Health Care Financing and Health Economics in Bangladesh. 2010, Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates Inc

Howlander S: Costing and Economic Analysis of Strengthening Union Level Facility for Providing Normal Delivery and Newborn Care Services in Bangladesh. 2011, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Population Council

Hutchinson P, Lance P, Guilkey David K, Shahjahan M, Haque S: Measuring the cost-effectiveness of a national health communication program in rural Bangladesh. J Health Commun. 2006, 11 (Suppl 2): 91-121.

LeFevre A, Shillcutt SD, Waters HR, Haider S, Arifeen SE, Mannan I, Seraji HR, Shah R, Darmstadt Gary L, Wall S, Williams E, Black R, Santosham M, Baqui A, the Pronjahnmo Study Group: Economic evaluation of neonaral care packages in a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Sylhet, Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2013, 91: 736-745. 10.2471/BLT.12.117127.

Levin A, Amin A, Rahman A, Saifi R, Barkat EK, Mozumder K: Cost-effectiveness of family planning and maternal health service delivery strategies in rural Bangladesh. Int J Health Plann Manag. 1999, 14: 219-233. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199907/09)14:3<219::AID-HPM549>3.0.CO;2-N.

Levin A, Amin A, Saifi R, Rahman A, Barkate K, Mozumder K: Cost-effectiveness of family planning and maternal and child health alternative service-delivery strategies in rural Bangladesh. 1997, Dhaka, Bangladesh: International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangldesh

Routh S, Barkat EK: An economic appraisal of alternative strategies for the delivery of MCH-FP services in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2000, 15: 115-132. 10.1002/1099-1751(200004/06)15:2<115::AID-HPM586>3.0.CO;2-6.

World Bank: Maintaining Momentum to 2015? An Impact Evaluation of Interventions to Improve Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition in Bangladesh. 2005, Washington DC: World Bank

Soucat A, Levy-Bruhl D, De B, Gbedonou P, Lamarque JP, Bangoura O, Camara O, Gandaho T, Ortiz C, Kaddar M, Knippenberg R: Affordability, cost-effectiveness and efficiency of primary health care: the Bamako Initiative experience in Benin and Guinea. Int J Health Plann Manag. 1997, 12 (Suppl 1): S81-S108.

Hounton SH, Newlands D, Meda N, De B: A cost-effectiveness study of caesarean-section deliveries by clinical officers, general practitioners and obstetricians in Burkina Faso. Hum Resour Health. 2009, 7: 34-10.1186/1478-4491-7-34.

Newlands D, Yugbare-Belemsaga D, Ternent L, Hounton S, Chapman G: Assessing the costs and cost-effectiveness of a skilled care initiative in rural Burkina Faso. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008, 13 (Suppl 1): 61-67.

Hounton S, Newlands D: Applying the net-benefit framework for analyzing and presenting cost-effectiveness analysis of a maternal and newborn health intervention. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7: e40995-10.1371/journal.pone.0040995.

Heller T, Kunthea S, Bunthoeun E, Sok K, Seuth C, Killam WP, Sovanna T, Sathiarany V, Kanal K: Point-of-care HIV testing at antenatal care and maternity sites: experience in Battambang Province, Cambodia. Int J STD AIDS. 2011, 22: 742-747. 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011262.

Skinner J, Rathavy T: Design and evaluation of a community participatory, birth preparedness project in Cambodia. Midwifery. 2009, 25: 738-743. 10.1016/j.midw.2008.01.006.

Becker-Dreps Sylvia I, Biddle Andrea K, Pettifor A, Musuamba G, Imbie David N, Meshnick S, Behets F: Cost-effectiveness of adding bed net distribution for malaria prevention to antenatal services in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 81: 496-502.

Fox-Rushby JA, Foord F: Costs, effects and cost-effectiveness analysis of a mobile maternal health care service in West Kiang, The Gambia. Health Policy. 1996, 35: 123-143. 10.1016/0168-8510(95)00774-1.

Fox-Rushby JA: The Gambia: cost and effectiveness of a mobile maternal health care service, West Kiang. World Health Statistics Quarterly. 1995, 48: 23-27.

Horton S, Sanghvi T, Phillips M, Fiedler J, Perez-Escamilla R, Lutter C, Rivera A, Segall-Correa AM: Breastfeeding promotion and priority setting in health. Health Policy Plan. 1996, 11: 156-168. 10.1093/heapol/11.2.156.

Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, Mahapatra R, Borghi J, Rath S, Gope R, Mahto D, Sinha R, Lakshminarayana R, Patel V, Pagel C, Prost A, Costello A: Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010, 375: 1182-1192. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0.

Kumar M, Birch S, Maturana A, Gafni A: Economic evaluation of HIV screening in pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in India. Health Policy. 2006, 77: 233-243. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.014.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM: Home-based neonatal care: summary and applications of the field trial in rural Gadchiroli, India (1993 to 2003). J Perinatol. 2005, 25 (Suppl 1): S108-S122.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD: Management of birth asphyxia in home deliveries in rural Gadchiroli: the effect of two types of birth attendants and of resuscitating with mouth-to-mouth, tube-mask or bag-mask. J Perinatol. 2005, 25 (Suppl 1): S82-S91.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD: Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: Field trial in rural India. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1955-1961. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03046-9.

Berman P, Quinley J, Yusuf B, Anwar S, Mustaini U, Azof A, Iskandar I: Maternal tetanus immunization in Aceh Province, Sumatra: the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies. Soc Sci Med. 1991, 33: 185-192. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90179-G.

Guyatt HL, Gotink MH, Ochola SA, Snow RW: Free bednets to pregnant women through antenatal clinics in Kenya: A cheap, simple and equitable approach to delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2002, 7: 409-420. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00879.x.

Population Council Frontiers in Reproductive H: Kenya: reproductive tract infections. On-site antenatal syphilis services are cost-effective. 2001, Washington, D.C: Population Council, Frontiers in Reproductive Health

Fonck K, Claeys P, Bashir F, Bwayo J, Fransen L, Temmerman M: Syphilis control during pregnancy: effectiveness and sustainability of a decentralized program. Am J Public Health. 2001, 91 (5): 705-707.

Jenniskens F, Obwaka E, Kirisuah S, Moses S, Yusufali FM, Achola JO, Fransen L, Laga M, Temmerman M: Syphilis control in pregnancy: decentralization of screening facilities to primary care level, a demonstration project in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995, 48 (Suppl): S121-S128.

Colbourn T, Nambiar B, Bondo A, Makwenda C, Tsetekani E, Makonda-Ridley A, Msukwa M, Barker P, Kotagal U, Williams C, Davies R, Webb D, Flatman D, Lewycka S, Rosato M, Kachale F, Mwansambo C, Costello A: Effects of quality improvement in health facilities and community mobilization through women’s groups on maternal, neonatal and perinatal mortality in three districts of Malawi: MaiKhanda, a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Int Health. 2013, 5 (3): 180-195. 10.1093/inthealth/iht011.

Colbourn T, Nambiar B, Costello A: MaiKhanda: final evaluation report. The impact of quality improvement at health facilities and community mobilisations by women's groups on birth outcomes: an effectiveness study in three districts of Malawi. 2013, London: The Health Foundation

Lewycka S, Mwansambo C, Rosato M, Kazembe P, Phiri T, Mganga A, Chapota H, Malamba F, Kainja E, Newell M, Pulkki-Brannstrom AM, Skordis-Worrall J, Bvergnano S, Osrin D, Costello A: Effect of women’s groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): a factorial, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2013, 381: 1721-1735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61959-X.

Kruk ME, Pereira C, Vaz F, Bergstrom S, Galea S: Economic evaluation of surgically trained assistant medical officers in performing major obstetric surgery in Mozambique. BJOG: An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007, 114: 1253-1259. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01443.x.

Borghi J, Thapa B, Osrin D, Jan S, Morrison J, Tamang S, Shrestha BP, Wade A, Manandhar DS, Costello AMDL: Economic assessment of a women’s group intervention to improve birth outcomes in rural Nepal. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1882-1884. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67758-6. XPT: Journal article

Broughton E, Saley Z, Boucar M, Alagane D, Hill K, Marafa A, Asma Y, Sani K: Cost-effectiveness of a quality improvement collaborative for obstetric and newborn care in Niger. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2013, 26 (3): 250-261. 10.1108/09526861311311436.

Ndiaye P, Kini GA, Adama F, Idrissa A, Tal-Dia A: Obstetric urogenital fistula (OUGF): cost analysis at the Niamey National Hospital (Niger). Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2009, 57: 374-379. 10.1016/j.respe.2009.04.010.

Nwakoby B, Akpala C, Nwagbo D, Onah B, Okeke V, Chukudebelu W, Ikeme A, Okaro J, Egbuciem P, Ikeagu A: Community contact persons promote utilization of obstetric services, Anambra State, Nigeria. The Enugu PMM Team. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997, 59 (Suppl 2): S219-S224.

Shehu D, Ikeh AT, Kuna MJ: Mobilizing transport for obstetric emergencies in northwestern Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997, 59: S173-S180.

Duke T, Willie L, Mgone JM: The effect of introduction of minimal standards of neonatal care on in-hospital mortality. P N G Med J. 2000, 43: 127-136.

Witter S, Dieng T, Mbengue D, Moreira I, De Vincent B: The national free delivery and caesarean policy in Senegal: evaluating process and outcomes. Health Policy Plan. 2010, 25: 384-392. 10.1093/heapol/czq013.

Johnston HB, Gallo MF, Benson J: Reducing the costs to health systems of unsafe abortion: A comparison of four strategies. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007, 33: 250-257. 10.1783/147118907782101751.

Mbonye AK, Hansen KS, Bygbjerg IC, Magnussen P: Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: the incremental cost-effectiveness of a new delivery system in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 685-693. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.016.

Mbonye AK, Hansen K, Bygbjerg IC, Magnussen P: Effect of a community-based delivery of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy on treatment seeking for malaria at health units in Uganda. Public Health. 2008, 122: 516-525. 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.07.024.

Somigliana E, Sabino A, Nkurunziza R, Okello E, Quaglio G, Lochoro P, Putoto G, Manenti F: Ambulance service within a comprehensive intervention for reproductive health in remote settings: a cost-effective intervention. Trop Med Int Health. 2011, 16 (9): 1151-1158. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02819.x. XPT: Journal article

Nizalova Olena Y, Vyshnya M: Evaluation of the Impact of the Mother and Infant Health Project in Ukraine. IZA Discuss Pap. 2010, No. 4593 http://hdl.handle.net/10419/36054,

Hira SK, Bhat GJ, Chikamata DM, Nkowane B, Tembo G, Perine PL, Meheus A: Syphilis intervention in pregnancy: Zambian demonstration project. Genitourin Med. 1990, 66: 159-164.

Manasyan A, Chomba E, McClure EM, Wright LL, Krzywanski S, Carlo WA: Cost-effectiveness of essential newborn care training in urban first-level facilities. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: e1176-e1181. 10.1542/peds.2010-2158.

Sabin LL, Knapp AB, MacLeod WB, Phiri-Mazala G, Kasimba J, Hamer DH, Gill CJ: Costs and cost-effectiveness of training traditional birth attendants to reduce neonatal mortality in the Lufwanyama neonatal survival study (LUNESP). PLoS One. 2012, 7 (4): e35560-10.1371/journal.pone.0035560.

Kerber K, de Graft-Johnson J, Bhutta Z, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn J: Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007, 370: 1358-1369. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5.

International Monetary Fund: World Economic Outlook Database, April 2013. 2013, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/01/weodata/index.aspx: International Monetary Fund; 2013

World Bank: Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average). 2014, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF: World Bank; 2014

World Bank: GDP per capita (current US$). 2014, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD: World Bank

World Health Organization: Cost-effectiveness thresholds. 2014, Available at http://www.who.int/choice/costs/CER_thresholds/en/: World Health Organization; 2014,

Hoch J, Dewa C: A clinician’s guide to correct cost-effectiveness analysis: think incremental not average. Can J Psychiatr. 2008, 53 (4): 267-274.

Drake T: Priority Setting in Global Health: Towards a Minimum DALY Value. Health Econ. 2014, 23 (2): 248-252. 10.1002/hec.2925.

Walker N, Tam Y, Friberg I: Overview of the Lives Saved Tool (LiST). BMC Public Health. 2013, 13 (Suppl 3): S1-10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S1.

Simon J, Petrou S, Gray A: The valuation of prenatal life in economic evaluations of perinatal interventions. Health Econ. 2009, 18: 487-494. 10.1002/hec.1375.

Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, Brown R, Buxton M, Chawla A, Cook J, Glick H, Liljas B, Petitti D, Reed S: Good Research Practice for Cost-effectiveness alongside clinical trials: The ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force Report. Value Health. 2005, 8 (5): 521-533. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00045.x.

Thorn J, Noble S, Hollingsworth W: Timely and complete publication of economic evaluations alongside randomized controlled trials. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013, 31 (1): 77-85. 10.1007/s40273-012-0004-7.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/243/prepub

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by IDEAS, Informed Decisions for Actions to improve maternal and newborn health (http://ideas.lshtm.ac.uk), which is funded through a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Thanks also to Deepthi Wickremasinghe for helping to obtain full text articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LMJ prepared a protocol for the systematic review with advice from JS, AM, SC and CP. LMJ registered the review. LMJ and CP independently conducted the title and abstract review and the full-text review. LMJ led the data extraction, which was checked by CP. LMJ and CP assessed study quality. LMJ synthesized the findings and drafted the manuscript, with assistance from CP, AM, JS and SC. All authors approved the final manuscript.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0476-5.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mangham-Jefferies, L., Pitt, C., Cousens, S. et al. Cost-effectiveness of strategies to improve the utilization and provision of maternal and newborn health care in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 243 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-243

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-243