Abstract

Background

Preeclampsia is a disease with great variability in incidence across the world. The mortality is higher in lower income countries, where it is the leading cause of maternal mortality. This study aimed to determine the frequency of and risk factors for preeclampsia in a low income population from an urban area of Brazil.

Methods

A prospective case control study of 242 women of which 30 developed preeclampsia, 4 had gestational hypertension, 2 had superimposed hypertension, 11 had spontaneous abortion, 13 were lost to follow up and 192 had normal pregnancy. This latter group was considered the normotensive controls. The rate of preeclampsia and the risk of cardiovascular disease, after onset of preeclampsia, were determined.

Results

Of the 218 women who completed the study, the frequency of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy was 16.5% (36 of 218) and of preeclampsia was 13.8% (30 of 218). Women with preeclampsia had a higher body mass index (BMI), mean of 25.3 ± 4.8 compared to 23.5 ± 3.7 for the normotensive controls, p = 0.02. The risk of preeclampsia increased with BMI [Odds ratio (OR) 1.12, 95% Confidence Interval (CI = 1.02;1.24, p-value = 0.023)]. Women with preeclampsia developed chronic hypertension more often than normotensive controls (p = 0.043) and their systolic and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was elevated (p = 0.034). Women with preeclampsia had higher BMI even 5 years post-pregnancy (p = 0.008).

Conclusions

Women who are overweight or older have an increased risk of preeclampsia. Previous history of preeclampsia increases the risk of early onset of chronic hypertension. Therefore, effective preventive measures are needed, particularly women at lower social economic stratum who have less access to proper medical care and adequate nutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Preeclampsia is a heterogeneous disease unique to humans and is the leading cause of maternal and intrauterine mortalities [1, 2] and intrauterine growth restriction [3]. Because of maternal complications, there is usually a need for early interruption of the pregnancy. Preeclampsia increases the risk of maternal mortality in both developed (1.8%) and less developed countries (14%) [4–6] and it is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of women of child bearing age worldwide [7, 8]. Several factors including ethnicity, obesity, metabolic syndrome, excessive weight gain, multiparity, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and thrombophilias increase the risk of preeclampsia [1, 9]. Socio-economics also plays a role in the vulnerability of women to develop preeclampsia. Women with lower income have more difficulty in access to medical care, early diagnosis and proper screening and therapy, and they often have inadequate nutrition [10–12].

The principal cause of maternal mortality in Brazil is preeclampsia. This has been fostered by an increasing prevalence of obesity, hypertension and insulin resistance [13–15], along with an increasing incidence of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and auto-immune disorders [16]. Although there is universal health care in Brazil, there is still a need for improvement, principally with respect to women’s health [17].

Studies to date have determined preeclampsia rates by hospital discharge summaries or national registries [18–20]. But a limitation of this approach is the bias of those localities using a reference center in which the reported cases are more severe. However, to our knowledge there is no study evaluating the community based incidence of preeclampsia in Brazil or in low economy countries. In this study, we aimed to determine the rate of preeclampsia by recruiting pregnant women at their first medical visit in a community health post center in Natal, Brazil. We also evaluated their hypertensive status 5 years after the onset of preeclampsia.

Methods

Study design

A prospective study of pregnancy outcomes was conducted from August 2004 to July 2006 in the district of Bom Pastor, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, northeast Brazil to determine the incidence of preeclampsia. The district of Bom Pastor is located in the western region of Natal, with a population of 10,933 people of which 52% are female. In the district, 64.9% of women were of childbearing age (n = 3718), and of these 6.5% (n = 242) became pregnant during the study period. A total of 242 women were recruited, and the mean gestational age at enrollment was 18.4 ± 7.9 weeks. Eleven women (4.5%) had spontaneous abortion and 13 (5.4%) were lost to follow up, resulting in 218 women who were followed through the end of the pregnancy. Of these 218 women, 30 developed preeclampsia (13.7%), 4 had gestational hypertension (1.8%) and 2 (0.9%) had superimposed hypertension in pregnancy. In this study, we compared cases of preeclampsia to those who had a normotensive pregnancy (n = 182), (Table 1).

The household income for this population was 2.2 monthly Brazilian minimal wages (~US$ 440 monthly), (http://www.ibge.gov.br). Approximately 22% of the population had no schooling and 22% had an average of 3 years of education. The overall literacy rate for women was 55.9% (http://www.ibge.gov.br; http://www.natal.rn.gov.br/semurb/paginas/ctd-106.html).

Each subject was interviewed and examined by the same physician (EDM). Personal and family histories of diseases were determined. Anthropometric measurements were recorded at each visit. Blood was collected each trimester to assess complete blood count, liver function, lipid profile, and venereal disease (syphilis). HIV status was checked once during pregnancy. Urinalysis was completed each trimester. Since the goal was to determine the profile of pregnancy outcomes in a community health center there were no exclusion criteria.

A follow up study in a subgroup of women (n = 27) was performed five years after the initial recruitment. Of this group, 10 had preeclampsia and 17 had no history of preeclampsia. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was measured. Preeclampsia was defined by the Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program [21].

Ethical considerations

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte Ethical Committee (CEP-UFRN 89–02) and the Brazilian National Ethical Research Committee (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa- CONEP/MS 5060), with an amendment (CEP-UFRN 006–2011), all participants signed the informed consent.

Statistical analysis

The mean of continuous variables such as age and blood pressure were compared between the groups using the Student t-test. Qualitative variables such as presence of complications were analyzed by contingency tables using the Maximum Likelihood test to assess the hypothesis of association. Box plots were used to show the distribution of BMI. To estimate the effect of age and BMI as a risk for preeclampsia, a logistic regression model used age and BMI as predictors variables to determine the relative risk (RR) of preeclampsia using the formula: log(RR) = β 0 + β 1 AGE + β 2 BMI + error. The hypothesis of no association H 0:β i = 0 was rejected when the p value was less than 0.05. Comparisons of the continuous variable’s distributions assessed only in the second moment used the Mann–Whitney test, (p < 0.05). Parameters measured after delivery included BMI, parity, total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, urea, creatinine, microalbuminuria and Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM), which were analyzed as continuous variables. ABPM was determined in accordance with the International Academy of Cardiology [22, 23]. Cluster analysis of the districts in Natal was analyzed considering both income distribution and literacy rate. A Hierarchical Cluster with the Ward’s Method using the Squared Euclidian Distance was performed to determine the dissimilarity among the districts.

Results

Of the 212 women who were studied until the end of the pregnancy, 30 had preeclampsia. Of those who developed preeclampsia, 20% (6 of 30) had severe preeclampsia and received anti-seizure therapy, and one woman developed HELLP syndrome. There was no difference in the number of prior gestations between the women who developed preeclampsia compared to the normotensive controls, 2.3 ± 3.0 and 2.5 ± 1.7 (p = 0.647), respectively, nor in the gestational age at recruitment, 19.6 ± 8.2 and 18.7 ± 7.8 weeks (p = 0.599), respectively, (Table 1). However, women who developed preeclampsia had a higher weight at enrollment than the normotensive controls, (63.9 ± 11.2 kg vs. 58.5 ± 9.3 kg, p = 0.038), (Table 1). The BMI at recruitment was also higher among women who developed preeclampsia (25.3 ± 3.9 vs. 23.7 ± 3.6 kg/m2, p = 0.020), Figure 1. Women with preeclampsia also had higher creatinine 0.7 ± 1.4 vs. 0.2 ± 0.8 mg/dl (p = 0.006) (Table 1).

No association with family history of hypertension or preeclampsia was observed (Table 1). The risk of preeclampsia increased exponentially with age, (6% increase risk per year, p = 0.090), and as represented in Figure 2, and with BMI (12% increase risk for each unit of increased BMI, p = 0.023), determined by using a binary logistic model corrected by age and BMI, (Table 2), Figure 3. The level of schooling was lower in women with preeclampsia, with only 20% having completed high school (p = 0.025).

There was no difference in the weight of the newborn between children born of preeclampsia and normotensive controls pregnancies (p > 0.05). However, children born of a preeclampsia pregnancy had a lower APGAR at birth (p = 0.014), but with a significant recovery at 5 minutes APGAR (p = 0.039), Table 3.

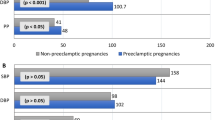

A subset of subjects which included 10 cases and 17 controls was followed 5 years post-delivery. BMI at 5-year follow up were still higher among women who had prior preeclampsia (28.5 ± 1.5 vs. 25.0 ± 2.8 kg/m2, p = 0.013). Half of the follow up group with prior preeclampsia (5/10) developed chronic hypertension while only 11.8% (2/17) did in this with prior normotensive pregnancy (p = 0.040) (Table 4). All hypertensive cases were being treated. Even so, women with prior preeclampsia had significantly higher ABPM 24 hour diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.017) as well as ABPM awake-Diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.010) when compared to the normotensive controls (Table 4). There was no difference in the growth of the child when considering the type of pregnancy and the gestational age at delivery (Table 5).

Because of the high rate of preeclampsia observed, we analyzed whether socio-economics or literacy were similar in other districts in Natal and other localities in Brazil. Cluster analysis of the district showed that there were five clusters in Natal, and the studied district fell into the cluster with high population density and lower socioeconomics (Additional file 1: Table S1). In general, women in the lower social economic stratum are more vulnerable with respect to access to medical care, adherence to treatment and adequate nutrition.

Discussion

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy have a high incidence worldwide. Over 500,000 women die yearly due to causes related to pregnancy and the majority of these deaths occur in less developed countries [12, 24]. In addition, children born of a preeclampsia pregnancy have an increased risk of endocrine, nutritional, metabolic, and hematopoietic diseases [25–27]. Anecdotal reports indicate that all hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are high in Brazil, although there is no epidemiological study showing the actual frequency of preeclampsia in Brazil. In this Brazilian cohort, the incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was 16.9% and the frequency of preeclampsia was 13.8%. We anticipate that the rates of preeclampsia in other underserved areas may also be higher than expected [28].

The cause of preeclampsia is unknown, but previous studies have found an association of elevated BMI and preeclampsia [29]. Women with lower body mass index (BMI) have a lower risk of preeclampsia than women at normal or higher BMI [6, 30, 31]. The mechanism by which obesity increases the incidence of preeclampsia could include increased insulin resistance or inflammation [32, 33]. Insulin resistance has been associated with endothelial dysfunction [14, 15], and increased secretion of endothelin 1, a potent vasoconstrictor [34]. In addition, insulin resistance results in reduction of nitric oxide, increasing the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases [20, 35–40]. Association of higher BMI and preeclampsia was also seen in our cohort, although the mean BMIs for our study population are not those of severe obesity. Women of Latin American origin showed a strong association with higher BMI and preeclampsia [41, 42]. These changes may be the result of the socio-economic changes that have occurred in Brazil with increased urbanization and substantial dietary changes with increased availability of food [43, 44].

In addition to obesity, others have hypothesized that preeclampsia could be related to the inflammatory response induced by infectious agents. Studies have shown that women with periodontal disease have increased risk of preeclampsia [10, 17]. A metanalysis of observational studies indicated that the risk of preeclampsia was increased in pregnant women with urinary tract infection and periodontal disease [10, 17, 45, 46]. Overall, there is poor dental health in this population and the majority of women have gingivitis and dental cavities (personal observation, SMBJ), although these issues were not assessed in this study.

The World Health Organization indicates that the frequency of cesarean section is ~15% worldwide [47], with the rate in Africa being about 4% [38], and 30% in the United States, [48, 49]. Overall the rate of C section is high in Brazil, and even higher in women who have access to private health insurance, with rates greater than 50% [50, 51]. But preeclampsia is a condition that may warrant a cesarean delivery [52], because the need to save the child and to avoid greater complications of the preeclampsia, including eclampsia. Although the use of magnesium sulfate has decreased mortality and morbidity [53], the severity of the preeclampsia leads to resolution of the pregnancy with indication of cesarean section as a mean to decrease the fetal and maternal complications [48, 54]. In this study, the frequency of cesarean section in women with normal pregnancy was 22%, compared with 60% in women with preeclampsia. In a previous, study of a similar population of women with lower income; the rate of cesarean deliveries with severe preeclampsia was 80%, whereas the rate of cesarean section in the normotensive controls group was 20% [55].

Children born of a preeclampsia pregnancy have more long term complications [25, 26]. In addition, the impact of the inflammation due to the preeclampsia status on the fetus is still not fully understood. At one year post-partum, the subset of children born to this cohort showed normal growth and gain of weight. This outcome may have been influenced by the careful monitoring of the mother during the pregnancy, since all women who develop preeclampsia were enrolled promptly into therapy; different from our findings from a referral center in which we observed more severe cases with the majority of them without adequate care during the pregnancy [55]. However, additional term follow up is needed to assess long-term outcomes for children of women with preeclampsia.

A follow up of a subgroup of the study population revealed that 50% of the women who had preeclampsia were still hypertensive 5 years after delivery. Their BMI was significantly higher than women who had a non-hypertensive pregnancy. Increased body weight is a potentially modifiable risk factor; controlling weight could help reduce the risk of maternal complications such as preeclampsia. In addition, there is a need for careful post-partum follow-up to better manage hypertension and to counsel regarding BMI. Although we did not find an increased risk of preeclampsia with family history of chronic hypertension or preeclampsia, as we had previously observed, (55) this could be because most of these cases were considered mild, except 6 preeclampsia cases that needed magnesium sulfate and 1 HELLP syndrome case. In summary, we found that women who are underserved in terms of health care had a higher frequency of preeclampsia and that preeclampsia is a frequent disease in this population. In addition, higher BMI and a hypertensive condition may contribute to earlier onset of cardiovascular disease. As obesity and diabetes continue to rise in prevalence in countries like Brazil, more attention post-delivery is warranted to decrease long term complications.

Conclusions

Higher BMI and older age during the pregnancy were associated with hypertension. History of preeclampsia increases the risk of early onset of chronic hypertension.

Authors’ information

EM is an Obstetrician working with a team of researchers focusing on understanding the risk factors to developing Preeclampsia. These data set the stage to estimate the risk of preeclampsia in the context of changes in the disease pattern in Brazil and at the same time is helping to tease out the influence of genetics versus environment in the risk of developing preeclampsia and its complications.

References

Sibai BM, Spinnato JA, Watson DL, Hill GA, Anderson GD: Pregnancy outcome in 303 cases with severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1984, 64: 319-325.

Sibai BM, Abdella TN, Anderson GD: Pregnancy outcome in 211 patients with mild chronic hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 1983, 61: 571-576.

Belghiti J, Kayem G, Tsatsaris V, Goffinet F, Sibai BM, Haddad B: Benefits and risks of expectant management of severe preeclampsia at less than 26 weeks gestation: the impact of gestational age and severe fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 205: 465-466.

Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Roberts JM: Racial/ethnic differences in the monthly variation of preeclampsia incidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 196: 324-325.

Cripe SM, O’Brien W, Gelaye B, Williams MA: Perinatal outcomes of Southeast Asians with pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus or preeclampsia. JImmigr Minor Health. 2012, 14: 747-753.

Barton JR, Sibai BM: Prediction and prevention of recurrent preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 112 (2 Pt 1): 359-372.

Sibai BM: Preeclampsia as a cause of preterm and late preterm (near-term) births. Semin Perinatol. 2006, 30: 16-19.

Von DP, Magee L: What matters in preeclampsia are the associated adverse outcomes: the view from Canada. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 20: 110-115.

Sibai BM: Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 206: 470-475.

Conde-Agudelo A, Villar J, Lindheimer M: Maternal infection and risk of preeclampsia: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 198: 7-22.

Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Diaz-Rossello JL: Epidemiology of fetal death in Latin America. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 371-378.

Delahaije DH, van Kuijk SM, Dirksen CD, Sep SJ, Peeters LL, Spaanderman ME, et al: Cost-effectiveness of recurrence risk guided care versus care as usual in women who suffered from early-onset preeclampsia including HELLP syndrome in their previous pregnancy (the PreCare study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010, 10: 60-

Strufaldi MW, Silva EM, Puccini RF: Metabolic syndrome among prepubertal Brazilian schoolchildren. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008, 5: 291-297.

Valerio EG, Muller AL, Martins-Costa SH, Lopes Ramos JG, Rodini G: Are insulin resistance index, IGF-1 and metabolic syndrome components correlates with severe preeclampsia?. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011, 30: 302-310.

Strufaldi MW, da Silva EM, Puccini RF: Insulin resistance among Brazilian schoolchildren: association with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98: 1646-1650.

Ramos AV, Bastos-Rodrigues L, Resende BA, Friedman E, Campanha-Versiani L, Miranda DM, et al: The contribution of FTO and UCP-1 SNPs to extreme obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular risk in Brazilian individuals. BMC Med Genet. 2012, 13: 101-

Siqueira FM, Cota LO, Costa JE, Haddad JP, Lana AM, Costa FO: Maternal periodontitis as a potential risk variable for preeclampsia: a case–control study. J Periodontol. 2008, 79: 207-215.

Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK: Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987–2004. Am J Hypertens. 2008, 21: 521-526.

Payne B, Magee LA, Cote AM, Hutcheon JA, Li J, Kyle PM, et al: PIERS proteinuria: relationship with adverse maternal and perinatal outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011, 33: 588-597.

Menzies J, Magee LA, Macnab YC, Ansermino JM, Li J, Douglas MJ, et al: Current CHS and NHBPEP criteria for severe preeclampsia do not uniformly predict adverse maternal or perinatal outcomes. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2007, 26: 447-462.

Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 183: S1-S22.

O’Brien E, Staessen JA: Critical appraisal of the JNC VI, WHO/ISH and BHS guidelines for essential hypertension. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2000, 1: 675-682.

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves JW, Hill MN, et al: Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich ). 2005, 7: 102-109.

Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B: Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2012, 36: 56-59.

Saadat M, Nejad SM, Habibi G, Sheikhvatan M: Maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with preeclampsia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 46: 255-259.

Habli M, Levine RJ, Qian C, Sibai B: Neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and in normotensive pregnancies that delivered at 35, 36, or 37 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007, 197: 406-407.

Abramovici D, Friedman SA, Mercer BM, Audibert F, Kao L, Sibai BM: Neonatal outcome in severe preeclampsia at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation: does the HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome matter?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999, 180 (1 Pt 1): 221-225.

Saftlas AF, Olson DR, Franks AL, Atrash HK, Pokras R: Epidemiology of preeclampsia and eclampsia in the United States, 1979–1986. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990, 163: 460-465.

Rudra CL, Williams MA: BMI as a modifying factor in the relations between age at menarche, menstrual cycle characteristics, and risk of preeclampsia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005, 21: 200-205.

Sibai BM, Gordon T, Thom E, Caritis SN, Klebanoff M, McNellis D, et al: Risk factors for preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women: a prospective multicenter study. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995, 172 (2 Pt 1): 642-648.

Belogolovkin V, Eddleman KA, Malone FD, Sullivan L, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, et al: The effect of low body mass index on the development of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007, 20: 509-513.

Walsh SW: Obesity: a risk factor for preeclampsia. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 18: 365-370.

McDonald SD, Yusuf S, Walsh MW, Lonn E, Teo K, Anand SS, et al: Increased cardiovascular risk after pre-eclampsia in women with dysglycaemia. Diabet Med. 2013, 30: e1-e7.

Marasciulo FL, Montagnani M, Potenza MA: Endothelin-1: the yin and yang on vascular function. Curr Med Chem. 2006, 13: 1655-1665.

Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, Lie RT: Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001, 323: 1213-1217.

Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Klungsoyr K, Irgens LM, Vikse BE, Vatten LJ, et al: Cardiovascular mortality after pre-eclampsia in one child mothers: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ. 2012, 345: e7677-

Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA: Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1797-1803.

Wikstrom AK, Haglund B, Olovsson M, Lindeberg SN: The risk of maternal ischaemic heart disease after gestational hypertensive disease. BJOG. 2005, 112: 1486-1491.

Wikstrom AK, Stephansson O, Cnattingius S: Previous preeclampsia and risks of adverse outcomes in subsequent nonpreeclamptic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 204: 148-6.

Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ: Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007, 335: 974-

Fortner RT, Pekow P, Solomon CG, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L: Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and risk of hypertensive pregnancy among Latina women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 200: 167-

Fortner RT, Pekow PS, Whitcomb BW, Sievert LL, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L: Physical activity and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy among Hispanic women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011, 43: 639-646.

Vitolo MR, Bueno MS, Gama CM: Impact of a dietary counseling program on the gain weight speed of pregnant women attended in a primary care service. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2011, 3: 58-59.

Moreira MA, Cabral PC, Ferreira HS, Lira PI: Overweight and associated factors in children from northeastern Brazil. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2012, 88: 347-352.

Hsu CD, Witter FR: Urogenital infection in preeclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995, 49: 271-275.

Virk J, Hsu P, Olsen J: Socio-demographic characteristics of women sustaining injuries during pregnancy: a study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. BMJ Open. 2012, 2 (4):

Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Vogel J, Carroli G, Lumbiganon P, Qureshi Z, et al: Moving beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2013, 381: 1747-1755.

Okafor UV, Ezegwui HU: Cesarean delivery in preeclampsia and seasonal variation in a tropical rainforest belt. J Postgrad Med. 2010, 56: 21-23.

Chu K, Cortier H, Maldonado F, Mashant T, Ford N, Trelles M: Cesarean section rates and indications in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country study from Medecins sans Frontieres. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e44484-

Freitas PF, Drachler ML, Leite JC, Grassi PR: Social inequalities in cesarean section rates in primiparae, Southern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2005, 39: 761-767.

Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gulmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, et al: Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007–08. Lancet. 2010, 375: 490-499.

Brink A, Akande W, Moodley J, Hague W, Hall D, Steyn W, et al: Hypertension in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2002, 13: 68-72.

O’Connor HD, Hehir MP, Kent EM, Foley ME, Fitzpatrick C, Geary MP, et al: Eclampsia: Trends in Incidence and Outcomes over 30 Years. Am J Perinatol. 2012

Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al: Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006, 367: 1819-1829.

Bezerra PC, Leao MD, Queiroz JW, Melo EM, Pereira FV, Nobrega MH, et al: Family history of hypertension as an important risk factor for the development of severe preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010, 89: 612-617.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/13/159/prepub

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Bom Pastor Health Post Center and to the Health Agents for the support and help with participant’s recruitment. We are also thankful to the participants and to the Fundação de Apoio a Pesquisa no Rio Grande do Norte (FAPERN) for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EM wrote the proposal, participated in data collection, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. FVMP, GRM, DM and MFZ participated in data collection and revised the manuscript; JWQ performed data analysis and revised the manuscript; PD drafted and revised the manuscript. SMBJ and ACA approved the proposal with some revisions, participated in data analysis and revised subsequent drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and approve its submission.

Electronic supplementary material

12884_2012_1304_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1: Cluster analysis of population density, income and literacy for the Natal Districts. (*) Based in the 2010 census, which showed that population was 801,164 people. Note that Bom Pastor District belong to cluster one. (DOC 30 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dantas, E.M.d.M., Pereira, F.V.M., Queiroz, J.W. et al. Preeclampsia is associated with increased maternal body weight in a northeastern Brazilian population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, 159 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-159

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-159