Abstract

Background

To explore current status and choices regarding diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD) among physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists in China via a national survey.

Methods

The cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted from November, 2010 to July, 2011. Six hundreds and twelve doctors from different cities in China were recruited for this study.

Results

68.6% (n=420) and 23.9% (n=146) of doctors have read the national and international guidelines, respectively. There was a larger proportion of movement disorders specialists reading the guidelines, in contrast to physicians and general neurologists (P<0.001). Up to 76.4% (n=465) and 81.8% (n=498) of doctors would choose standard oral levodopa test and conventional MRI(with T1 and T2), respectively; Whereas susceptibility weighed imaging(SWI)(16.1%; n=98), transcranial sonography (TCS) (1.8%; n=11) and functional neuroimaging test, such as single photon emission computed tomography(SPECT) (10.2%; n=62) and positron emission tomography(PET)(13.3%; n=81) were less used for suspected patients with PD in clinical practice. Doctors at different levels or from different hospitals and cities would choose different medication for motor complications and non-motor symptoms of patients with PD, in addition to initial drug selection for newly diagnosed PD. Doctors who had read the guidelines had significantly better knowledge of medication selections for PD under specific circumstances.

Conclusions

Compared with commonly employed standard oral levodopa test and conventional MRI, SWI complements MRI, TCS and functional neuroimaging were less performed for diagnosis of PD in clinical practice in China. The choices of diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategy of PD vary among physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists. Guideline awareness is markedly beneficial to reasonable PD medications strategy in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Recently, epidemiological investigations indicated that there were approximately at least two million patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in China, accounting for 2/5 of the whole PD patients in the world [1]. Over the past three decades, significant progresses have been achieved on the diagnosis and treatment of PD in China. So far, the academic Chinese guidelines (First version(2006) and updated version (2009)) on the treatment of PD have been published by Chinese Parkinson’s Disease & Movement Disorders Society (CPDMDS) in recent years [2, 3], respectively, soon after the dissemination of the counterparts from American Academy of Neurology (AAN) [4–7], European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom [8]. It seems that the gap of diagnosis and management of PD patients is narrowing between China and Western Countries. However, the practical status of choices and opinions regarding diagnosis and treatment of PD among Chinese doctors is unknown unfortunately [9]. It is believed as a key influential factor to determine the actual benefit for patients [10–13].

In China, in addition to movement disorders specialists, both general neurologists and physicians are caring for PD patients. Each province has one capital city (such as Nanjing city as capital city of Jiangsu Province and Guangzhou city as capital of Guangdong Province) with integrated financial and economic centers. More medical resources were distributed in a few tertiary class hospitals in capital cities with over 1000 beds, followed by secondary class hospitals mostly located in the county with over 400 beds and primary health service centers [14, 15]. The movement disorders clinics and associated centers only exist in part of tertiary hospitals, and the resources could not satisfy the need of most patients with PD. In many cases, both general neurologists and physicians are taking the responsibility for diagnosis and treatment of PD patients. Therefore, the opinions from physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists in the clinical practice for PD will be diverse, which will have significant influence on the actual benefits of patients with PD.

Therein, we designed a national survey to investigate the opinions regarding diagnostic approaches for suspected PD, medications selection strategy for newly diagnosed PD, and motor complications & non-motor symptoms (NMSs) for follow-up patients among doctors at different levels.

Methods

Survey setting and sample

The study was sponsored by Chinese Parkinson’s Disease & Movement Disorders Society, Neurology Branch of Chinese Medical Association. From November, 2010 to July, 2011, questionnaires were randomly distributed to doctors attending National Neurological Congress, several Provincial Conferences or CME courses of PD held in Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Zhengzhou, Nanning and Hangzhou, respectively. In this survey, we classified the congress participants into three categories by their specialties and sub-specialties: A movement disorders specialist is a neurologist who has taken additional training in the subspecialty in neurology called movement disorders (as compared to other subspecialties in neurology) and regularly attends the movement disorders clinics; A neurologist who specializes in general neurology rather than movement disorders, is classified as general neurologists; Physicians are the doctors who did not work in neurology department, including general physicians and internal medicine specialists.While family physicians were not included in this survey. All of the abovementioned three categories of doctors had qualified medical licenses issued by the Chinese Public Health Administration.

Finally, a total of 900 questionnaires were distributed, 768 questionnaires were returned (response rate 85.3%), and 612 (effective rate 79.7%) questionnaires with complete demographic data were available for further evaluation (Figure 1). Of the 612 participants, 328(53.6%) were male. 248(40.5%) were below 35 and 352(57.5%) were 35–60 years old. 406(66.3%) responders came from tertiary hospitals, only 181(29.6%) and 25(4.1%) came from secondary hospitals and private clinics. Majority of the participants were general neurologists (70.8%, n=433) rather than physicians (14.7%, n=90) and movement disorder specialists (14.5%, n=89).

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire (Additional file 1) was designed by three of the authors (Dr. Gang Wang, Dr. Wei Chen and Dr. Sheng-Di Chen) with approval from the Research Ethics Committee, Ruijin Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. It covered three sections: (1) Continuing Medical Educations(CME) & research experiences for PD: consisting of guideline reading, specialty information source, CME activity frequency, PD patients to provide consultation service monthly on average, research papers published, etc.; (2) Initial diagnostic approaches for PD patients: including choices of a standard oral levodopa test, conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), susceptibility weighed imaging (SWI), transcranial sonography (TCS), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET), in addition to assessment of putative pre-motor symptoms of PD; (3) Strategy on PD management: comprising of initial medications choices for newly diagnosed PD, how to deal with wearing-off phenomenon, peak-dose dyskinesia, and some common non-motor symptoms, including psychosis, dementia, depression and restless legs syndrome. The response categories were in multiple-choice format for easily completing. It took about 20–30 min for finishing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, with student’s t test for comparing group means and chi-squared analysis for comparing proportions. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

CME & research experiences for PD

Of the 612 participants, 68.6% (n=420) and 23.9% (n=146) have read the national and international guidelines, respectively. There was a larger proportion of movement disorders specialists (75/89, 84.3%) reading the national guideline, in contrast to general neurologists (302/433, 69.7%) and physicians (43/90, 47.8%) (P<0.001). The situation was similar for the international guidelines reading (51.7% for movement disorders specialists VS. 19.6% for general neurologists VS. 16.7% for physicians; P<0.001). There were 72.9% (n=446) of responders caring for below 10 PD patients each month; 17.8% (n=109) 10–30, and 5.4% (n=33) above 30 PD patients monthly. However, 3.8% (n=23) of those have never diagnosed and treated PD patients before, most of whom are from secondary hospitals or private clinics. There were more movement disorders specialists (48/89, 53.9%) caring for more than 10 PD patients each month, than the general neurologists (90/433, 20.8%) and physicians (4/90, 4.4%) (P<0.001).

From the survey, information with respect to the current advances in PD was most frequently obtained from lectures of movement disorders specialists (68.0%; n=416), followed by professional journals (59.8%; n=366), movement disorders textbooks (57.8%; n=354), guidelines (50.8%; n=311) and information from the pharmaceutical sales representatives (14.9%; n=91). Regarding CME activity frequency for PD, 54.2% (n=332) of participants attended once or twice every year. Only 18.8% (n=115) took part in CME activities more than 3 times each year. 26.1% (n=160) never attended any programs before, which included 48.9% (44/90) physicians, 25.1% (109/433) general neurologists, and 7.9%(7/89) movement disorders specialists. With respect to papers published for PD, up to 80.6% (n=493) participants had never published any article. Only 17.1% (n=105) and 9.5% (n=58) had published papers for clinical studies and basic researches on PD, respectively. There were 101 (16.5%) responders undertaking basic research of PD at the same time of regular clinical works at present.

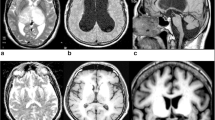

Initial diagnostic approaches for PD

Most participants, 76.4% (n=465), would adopt standard oral levodopa test as differential diagnosis method for patients with suspected PD. Conventional cranial MRI with T1 and T2 weighted images were performed by 81.8% (n=498) of those surveyed for diagnosis and differential diagnosis for PD. A small proportion of the responders would take SWI (16.1%; n=98), TCS (1.8%; n=11) and functional neuroimaging, such as SPECT (10.2%; n=62) and PET (13.3%; n=81) for PD diagnosis.

As putative pre-motor symptoms of PD, hyposmia, REM sleep behavior disorder(RBD), constipation, anxiety & depression were separately recognized as regular assessment items in the clinic by 42.5% (n=259), 43.5% (n=265), 36.3% (n=221) and 41.7% (n=254) of participants. There were significant differences regarding selection of diagnostic methods and putative pre-motor symptoms including hyposmia, RBD and constipation across the three doctor categories. Movement disorders specialists had a relatively higher cognition for related diagnostic methods (Table 1).

Strategy on PD management

Initial medications for newly diagnosed PD

With regard to initial medications for PD patients aged below 65 years without cognitive impairments (CI), dopamine agonists were employed by 42.9% (n=210) of 489 participants, followed by levodopa (33.5%) and MAO-B inhibitors (12.7%). Meanwhile, levodopa was used by 56.6% (n=277) of those surveyed for PD patients aged above 65 years or with CI (Table 2).

Motor complications treatment

For patients with wearing-off phenomenon, the most common therapeutic strategy was a switch from standard levodopa to CR levodopa (48.3%; n=236) among those surveyed. Additionally, enhancement of levodopa frequency (38.2%; n=187) and usage of some additives, such as dopamine agonists (40.1%, n=196) and COMT or MAO-B inhibitors (41.5%, n=203) were also regularly employed; 44.6% (n=218) of participants would reduce levodopa dose and add its frequency for patients with peak-dose dyskinesia, whereas only 14.5% (n=71) of those surveyed would choose amantadine for such condition (Table 2).

Non-motor symptoms(NMSs) treatment

Regarding medication selection for frequent NMSs, over 45.8% of responders employed Olanzapine rather than Clozapine (22.9%) for PD patients with psychosis. Memantine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and huperzine A were separately chosen by 37.8% (n=185), 53.8% (n=263), 16.8% (n=82), and 25.4% (n=124) of participants to improve CI in PD patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (59.7%; n=292) were most popular agents for selecting to treat depression symptoms of PD patients. Only 20.7% and 37.8% of participants prefer to choose tricyclic antidepressants and pramipexole to deal with depression, respectively. Dopamine agonists, benzodiazepines and levodopa were selected by 30.5%, 25.2% and 28.6% of participants to deal with restless legs syndrome, respectively (Table 2).

There was a relatively high level of knowledge on therapeutic strategy among movement disorders specialists (Table 2) and those from tertiary hospitals and capital cities (Table 3). Doctors who had read the guidelines had significantly better knowledge of medication selections for PD under specific circumstances (Table 4).

Discussion

This survey summarized general recognitions and opinions on the diagnosis and treatment of PD since the publication and dissemination of the first edition of Chinese PD diagnosis criteria and treatment guideline in China in 2006. With global populations aging, there are more than two million PD patients in China by rough estimation, accounting for 40% PD patients in the world, which brings heavy economic burden to the communities and families [16]. Managing the large population of PD patients in clinical practice and getting more and more updated information from the movement disorders specialists in the world, Chinese doctors have significantly improved their ability to make diagnosis and carry out reasonable therapy for PD over the past three decades. However, rare reports focus on medications selection strategy among professional levels of doctors in China [17].

As disclosed in this survey, in contrast to the Western Countries, where only the movement disorders specialists have the qualifications to provide consultations to the PD patients referred from other doctors, both general neurologists and physicians are caring for PD patients in China, in addition to movement disorders specialists. In fact, in China neither the numbers of movement disorders clinics nor the movement disorders specialists are sufficient to cope with the increasing PD patients. These differences in our survey among doctors at different levels for PD clinics may reflect at least two aspects: one is a relative shortage of medical professional human resources of movement disorders specialists in China, and the second is that the corresponding subspecialty fellowship training programs are lacking [14, 15, 18].

From the perspective of doctors, this survey displays the general features on PD in China: most of the participants have adopted the Chinese PD guideline to instruct the clinical practice of PD; Whereas, CME activity frequency are very low and few of those surveyed have published PD related articles. The phenomenon reflected marked shortcomings of academic summary in routine clinical works among most of the surveyed, especially general neurologists and physicians. These pitfalls partly explained the reasons for shortage of influential multi-center clinical studies and original basic research for PD in China compared to Western countries and Japan.

With respect to diagnostic methods for PD, standard oral levodopa test and conventional MRI were commonly considered for suspected patients in routine practice, whereas SWI, TCS and functional neuroimaging were less referred. In China, relatively expensive functional neuroimaging methods, such as SPECT and PET are not covered by Chinese medical insurances, and few patients would like to choose them. Additionally, for loss of knowledge and shortage of TCS experts in many hospitals, TCS is rarely accepted as a regular method. During the past few years, accumulating cross-sectional and longitudinal studies across the globe indicated that several putative clinical symptoms, including hyposmia [19], RBD [20], constipation [21], depression [22], might assist the early diagnosis and differential diagnosis for PD. In this survey, nearly 40% of those participants would use aforementioned non-motor symptoms as assistant information in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis for PD in clinical practice. Meanwhile, the difference is significant among different stratified doctors, except anxiety and depression. More studies on pre-motor symptoms are warranted to compare the sensitivity and specificity of each non-motor symptom.

As expected, specialties (physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists, Table 2), work places (the hospitals and the located cities, Table 3), and the Guideline awareness (Table 4) play important roles for reasonable PD medications selection strategy. There was a relatively high level of knowledge on therapeutic strategy under specific circumstance among movement disorders specialists and those from tertiary hospitals. However, the discrepancy between the guideline and clinical practice still exists on management of non-motor symptoms among all of those surveyed: Up to 45.8% of responders selected olanzapine to treat PD patients with psychosis, only 22.9% of those prescribed clozapine. The most often prescribed was donepezil, not rivastigmine, for PD with dementia, etc. Based on those observations, great efforts should be made to take the CME programs for physicians and general neurologists. Popularization activities of PD guideline across the country may be a visible strategy to obtain such purpose. In addition to establishment of clinical fellowship training system, the birth and development of movement disorders clinic team are necessary to standardize the diagnosis and treatment of PD. Interdisciplinary communication and cooperation among physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists are warranted to optimize the management of PD, especially for late stage patients with PD.

However, there are some limitations in this survey. As an on-the-spot investigation, the questionnaire was distributed at various conferences and CME courses. There was a potential selection bias as these meetings attendants were likely more academic active compared to those absentees. Additionally, there are rare studies for cognition and attitude of expertise in the public health populations in China so far. Therefore, a series of investigations focused on the expertise and CME will be promoted on a large scale in the future.

Conclusions

The national survey revealed that SWI complements MRI, TCS and functional neuroimaging were less performed for diagnosis of PD in clinical practice in China compared with commonly employed standard oral levodopa test and conventional MRI. The choices of diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategy of PD vary among physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists. Guideline awareness is markedly beneficial to reasonable PD medications strategy in China. Further CME programs on the diagnosis and management of PD patients are warranted especially for physicians and general neurologists caring for PD patients in China.

Abbreviations

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- NMSs:

-

Non-motor symptoms

- CME:

-

Continuing medical educations

- SWI:

-

Susceptibility weighed imaging

- TCS:

-

Transcranial sonography

- SPECT:

-

Single photon emission computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- RBD:

-

REM sleep behavior disorder

- CI:

-

Cognitive impairments.

References

Zhang ZX, Roman GC, Hong Z, et al: Parkinson's Disease in China: prevalence in Beijing, Xian, and Shanghai. Lancet. 2005, 365: 595-597.

Chen SD: (The Chinese movement disorders and Parkinson’s disease society): The guideline for management of Parkinson’s disease in China. Chin J Neurol. 2006, 39: 409-412.

Chen SD: (The Chinese movement disorders and Parkinson’s disease society): The guideline for management of Parkinson’s disease in China (second edition). Chin J Neurol. 2009, 42: 352-355.

Miyasaki JM, Shannon K, Voon V, et al: Practice parameter: evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology. 2006, 66: 996-1002. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000215428.46057.3d.

Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al: Practice parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology. 2006, 66: 983-995. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000215250.82576.87.

Suchowersky O, Gronseth G, Perlmutter J, Reich S, Zesiewicz T, Weiner WJ: Practice parameter: neuroprotective strategies and alternative therapies for Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology. 2006, 66: 976-982. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000206363.57955.1b.

Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, Zesiewicz T, Gronseth G, Weiner WJ: Practice parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology. 2006, 66: 968-975. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000215437.80053.d0.

National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK): Parkinson’s Disease: National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care [Internet]. 2006, Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG035.

Tian YY, Tang CJ, Wu J, Zhou JS: Parkinson's Disease in China. Neurol Sci. 2011, 32: 23-30.

Fargel M, Grobe B, Oesterle E, Hastedt C, Rupp M: Treatment of Parkinson's disease: a survey of patients and neurologists. Clin Drug Investig. 2007, 27: 207-218. 10.2165/00044011-200727030-00004.

Eggert K, Larisch A, Dodel R, Bormann C, Oertel WH: Awareness and knowledge of the clinical practice guideline on Parkinson's disease among German neurologists. Eur Neurol. 2009, 61: 216-222. 10.1159/000197106.

Larisch A, Oertel WH, Eggert K: Attitudes and barriers to clinical practice guidelines in general and to the guideline on Parkinson's disease. A National Survey of German neurologists in private practice. J Neurol. 2009, 256: 1681-1688. 10.1007/s00415-009-5178-3.

Willis AW, Schootman M, Evanoff BA, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA: Neurologist care in Parkinson disease: a utilization, outcomes, and survival study. Neurology. 2011, 77: 851-857. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c9123.

Guo Y, Shibuya K, Cheng G, Rao K, Lee L, Tang S: Tracking China's health reform. Lancet. 2010, 375: 1056-1058. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60397-2.

Shi FD, Jia JP: Neurology and neurologic practice in China. Neurology. 2011, 77: 1986-1992. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0ed3.

Wang G, Cheng Q, Zheng R, et al: Economic burden of Parkinson's disease in a developing country: a retrospective cost analysis in Shanghai, China. Mov Disord. 2006, 21: 1439-1443. 10.1002/mds.20999.

Wang G, Zhou HY, Zheng R, et al: Investigation on the clinical use of anti-Parkinson’s disease drugs for patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Neurol. 2006, 19: 336-338.

Wang XP, Zhang WF, Huang HY, Preter M: Neurology in the People's republic of China–an update. Eur Neurol. 2010, 64: 320-324. 10.1159/000321648.

Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, et al: Association of olfactory dysfunction with risk for future Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2008, 63: 167-173. 10.1002/ana.21291.

Iranzo A, Valldeoriola F, Lomena F, et al: Serial dopamine transporter imaging of nigrostriatal function in patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10: 797-805. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70152-1.

Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, et al: Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2001, 57: 456-462. 10.1212/WNL.57.3.456.

Walter U, Hoeppner J, Prudente-Morrissey L, Horowski S, Herpertz SC, Benecke R: Parkinson's Disease-like midbrain sonography abnormalities are frequent in depressive disorders. Brain. 2007, 130: 1799-1807. 10.1093/brain/awm017.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/12/155/prepub

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from the Chinese Parkinson’s Disease & Movement Disorders Society, Society for Neurology, Chinese Medical Association, and all the doctors who participated in this survey. We also thank Dr. Yue Huang at Neuroscience Research Australia, University of New South Wales for critical reading of the manuscript and Li-Hua Zhang for partial data collection. This work was supported by grants from the National Program of Basic Research (2011CB504104) of China, National "Twelfth Five-Year" Plan for Science & Technology Support (2012BAI10B03), Shanghai Key Project of Basic Science Research (10411954500), and Program for Outstanding Medical Academic Leader (LJ 06003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: GW, WC, SDC. Acquisition of data: WC, SC, QX, GW, SDC. Statistical analysis: WC, SC. Analysis and interpretation of data: WC, GW, SDC. Drafting of the manuscript: WC. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual contents: GW, SDC. Study supervision: QX, SDC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12883_2012_700_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Clinical practice for Parkinson’s disease (PD): A questionnaire among Chinese doctors (English version).(DOC 58 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Chen, S., Xiao, Q. et al. Current clinical practice for Parkinson’s disease among Chinese physicians, general neurologists and movement disorders specialists: a national survey. BMC Neurol 12, 155 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-155

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-155