Abstract

Background

Renal involvement in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection has been suggested to be due to a variety of immunological processes. However, the precise mechanism by which the kidneys are damaged in these patients is still unclear.

Case presentation

A 66 year old man presented with the sudden onset of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Concomitant with a worsening of hemolysis, his initially mild proteinuria and hemoglobinuria progressed. On admission, laboratory tests revealed that he was positive for hepatitis C virus in his blood, though his liver function tests were all normal. The patient displayed cryoglobulinemia and hypocomplementemia with cold activation, and exhibited a biological false positive of syphilic test. Renal biopsy specimens showed signs of immune complex type nephropathy with hemosiderin deposition in the tubular epithelial cells.

Conclusions

The renal histological findings in this case are consistent with the deposition of immune complexes and hemolytic products, which might have occurred as a result of the patient's underlying autoimmune imbalance, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and chronic hepatitis C virus infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extra-hepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection are diverse and appear during late middle age [1–3]. Among these, glomerulonephritis, arthritis, dermal vasculitis and sialadenitis are thought to develop as a result of the deposition of immune complexes (IC). It is generally accepted that B-cells infected with HCV clonally expand and produce autoantibodies [4, 5]. When antigen-bound, these autoantibodies, along with anti-HCV antibodies that target viral epitopes on the surface of cells are known to circulate as IC. These IC may participate in the pathogenesis of HCV-associated glomerulonephritis, though it has been difficult to detect these IC clinically. While immunosuppressive agents have been used successfully to diminish the production of autoantibodies, such a strategy is contraindicated in HCV patients since it would lead to an increase in viral replication.

We herein report the case of a patient with extra-hepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection that developed autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) prior to evident nephropathy.

Case presentation

A 66 year old man, with no prior history of blood transfusion, drug addiction, or the acquisition of tattoos, was diagnosed with hemolytic anemia in June of 2000. From the time he was 50, his yearly health check-ups have revealed faint hematuria (±) by urine dipstick testing, and he first exhibited proteinuria when he was 60 years old (see Table 1 for the patient's clinical history). At no time did the patient shows signs of liver dysfunction. Two of the patient's five brothers suffered from chronic liver disease (no further information was available) but none had a history of anemia.

In March of 2000, the patient was diagnosed with sudden onset anemia characterized by an increase in both mean corpuscular volume and corpuscular hemoglobin. Result of the Coomb's, acidified serum, sucrose hemolysis, and cold agglutinin tests were negative. Because spherocytes predominated in his hemogram and the results of his erythroresistant test (Ribiere's test) were positive, he was provisionally diagnosed as having hemolytic anemia caused by spherocytosis. Since he was asymptomatic, he was followed without medication.

Starting in September of 2000, the patient's hematuria and proteinuria progressed and his hemolysis worsened. Laboratory data began to indicate an increase in urinary protein excretion and a lowered serum protein concentration. The patient began to experience mild pretibial edema in March of 2001, at which time he was admitted to our hospital and a renal biopsy performed. Hematological tests at that time revealed the hyperchromic anemia with a macrocytic pattern and an increased numbers of reticulocytes. A hemogram (Figure 1) revealed the presence of unusually-shaped red blood cells (RBC), and polychromatic cells and spherocytes. Ferokinetic parameters such as Fe, unsaturated iron binding capacity (UIBC), ferritin and transferrin levels were all within the normal range. However, low levels of haptoglobin (less than 10 mg/dl; normal range = 41–341 mg/dl) and extremely high levels of erythropoietin (114 mU/ml; normal range = 8–36 mU/ml) were detected. Unlike his earlier results, his direct Coombs test was now positive and binding of IgG to the RBC surface was observed using anti-human globulin monospecific antibodies. Screening for the target antigen was performed using a panel of RBCs (Resolve® Panel C, Lot no. RC246, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Inc.) and revealed aggregation with all types of RBCs. Serum chemistry tests showed high levels of bilirubin and LDH, presumably caused by the excessive hemolysis (Table 2). Moderate levels of protein were found in the urine but serum total protein levels were slightly below the normal range. Urine dipstick testing gave a false positive result for occult blood detection. The slide precipitation test for syphilis also resulted in a false positive reading, though anti-cardiolipin β2GPI antibodies were absent. Hypocomplementemia with cold activation was demonstrated with the serum titer of CH50 being low though plasma titers were recoverable (his blood was collected in EDTA-containing tubes). Cryoprecipitation under cold storage (4°C, 72 hrs) followed by immunoelectrophoresis revealed the presence of a mixed type II cryogobulinemia. HCV viremia was confirmed using an HCV-RNA PCR test (genotype: 1B). Antibodies directed against HBV, HIV, EBV, and CMV were not found. An abdominal echogram revealed the absence of a splenomegaly and showed that his liver was of normal size and that it had a smooth surface.

Because the patient was symptom free, he was discharged after his renal biopsy and was followed without treatment. One year later, the patient had the same degree of hemolysis (hemoglobin = 7.4 g/dl, LDH = 756 U/l, total bilirubin = 2.7 g/dl) though his creatinine clearance had decreased (69.5 ml/min.). However, his urinary protein was stable (1.6 g/day) and his serum total protein recovered into the normal range (7.1 g/dl). His liver function was near normal (AST = 57 U/l, ALT = 19 U/l, albumin = 3.5 g/dl). And his level of HCV-RNA was slightly reduced (130 KIU/ml).

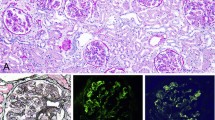

Renal histology (Figure 2 and 3): Five glomeruli were visualized in the patient's biopsy specimen. One of these glomeruli was intact while the other four, which were mildly lobulated, appeared to show a slight increase in mesangial cells and matrix. The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) was partially thickened and PAS staining revealed small spikes and bubble formation. No glomeruli had GBM cryoglobulinemic deposits. Small fibro-cellular crescents were found in two glomeruli. The proximal tubular epithelial cells contained numerous hemosiderin granules.

Immunofluorescence histochemistry demonstrated the presence of IgG in the GBM that was distributed in a course granular pattern, as well as the presence of IgA in the GBM and mesangial area. Staining for IgM and C3c was faint in the mesangial area, while C3d, C4d, C1q and fibrinogen were undetectable. Electron microscopy revealed small subepithelial deposits and a few para-mesangial deposits in the glomerulus.

Conclusions

In our patient, IgG autoantibody, which binds to RBCs, was detected in our patient using the direct antiglobulin test (Coomb's test), leading us to conclude that AIHA was the primary pathogenic mechanism that resulted in his hemolysis. Since his serum reacted with the full panel of RBCs tested, his autoantibodies probably recognized a common RBC surface antigen. Recent studies which suggest that the possible target antigens in AIHA are band 3 or 4.1 peptides, Rh, or glycophorin A, all of which are expressed on RBCs [6–8]. Our patient had not been treated with any antiviral drugs, such as ribavirin®, which have been shown to induce hemolytic anemia by a mechanism involving the oxidation-induced aggregation of band 3, leading to the binding of autologous anti-band 3 antibodies (natural antibody); when activated by complement, these antibodies induce intra- or extra-capillary hemolysis [9]. As a matter of course, ribavirin® was contraindicated in our case. In any event, a similar hemolytic mechanism might have resulted in this patient's production of circulating immune complex and free iron which lodged into his kidney.

HCV-associated glomerulonephritis is characterized by two types of histological changes i.e., membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and membranous nephropathy (MN) [10, 11]. Since the deposition of immunoglobulin and complement is detected on the glomeruli in this condition, these histological changes are thought to be due to immune complex disease [10–12]. In our case, proliferative changes were slight, and immunoglobulins and complement breakdown products were found to be deposited primarily in the GBM. Therefore, the primary histological changes in our patient's kidney were classified as being of the MN type. We speculate that glomerular deposition of IC occurred during chronic progression of the disease when the ratio of antigen and antibody was optimized.

There were no direct evidence of a causal relationship between chronic HCV infection and the occurrence of AIHA in our patient, though such a relationship has been suggested in four published reports [13–16]. Two of four patients that received an orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) were reported to have developed AIHA [13, 14]. Though the pathogenesis of AIHA was not discussed in those studies, it may have been related to the strong immunosuppressive therapy that the post-OLT patients received. Another reported case of AIHA was reported in a patient who suffered from B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia who was being treated with intermittent chemotherapy [15], while still another case was reported in a patient who had a complete congenital deficiency of IgA [16]. Thus, the immune systems of the above four patients were compromised prior to their development of hemolysis. What is not known is how chronic HCV infection leads to AIHA. The following evidence suggested that this patient's chronic immunological imbalance was triggered by chronic HCV infection. 1) HCV viremia was confirmed. 2) Our patient was of late middle age and this age group was shown to have a high frequency of extra-hepatic manifestations of HCV infection [1, 3]. 3) It is accepted that the presence of cryoglobulinemia, hypocomplementemia (cold activation), and a biological false positive on the syphilic test are characteristic abnormalities in patients with chronic HCV infection [1, 12, 17, 18]. In just recently paper, Ramos et al. reviewed highly suspected 17 cases with HCV-related AIHA [19]. These authors suggested that a higher prevalence of immunologic markers including cryoglobulinemia and hypocomplementemia all support the hypothesis that HCV-related AIHA has an autoimmune pathogenesis caused by chronic HCV infection.

We concluded that renal involvement in our patient post-dated his development of AIHA, which occurred against the backdrop of a progressive autoimmune imbalance induced by chronic HCV infection.

Abbreviations

- (HCV):

-

hepatitis C virus

- (IC):

-

immune complexes

- (AIHA):

-

autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- (RBC):

-

red blood cells

- (GBM):

-

glomerular basement membrane

- (MN):

-

membranous nephropathy

- (OLT):

-

orthotopic liver transplant

References

Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F, Simmonds P, Mellor J, Ben Yahia M, André C, Voisin MC, Intrator L, Zafrani ES, Duval J, Dhumeaux D: Extrahepatic Immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes. Ann Intern Med. 1995, 122: 169-173.

Mcmurray RW, Elbourne K: Hepatitis C virus and autoimmunity. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 26: 689-701.

Ohsawa I, Ohi H, Endo M, Fujita T, Seki M, Watanabe S: High prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies in elder patients with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Nephron. 1999, 82: 366-367. 10.1159/000045459.

Zignego AL, Macchia D, Monti M, Thiers V, Mazzetti M, Forschi M, Maggi E, Romabnani S, Gentilini P, Bréchot C: Infection of peripheral mononuclear blood cells by hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol. 1992, 15: 382-386.

Müller HM, Pfaff E, Goeser T, Kallinowski B, Solbach C, Theilmann L: Peripheral blood leukocytes serve as a possible extrahepatic site for hepatitis C virus. J Gen virol. 1993, 74: 669-676.

Lutz HU, Bussolino F, Flepp R, Fasler S, Stammler P, Kazatchkine MD, Arese P: Naturally occurring anti-band 3 antibodies and complement together mediate phagocytosis of oxidatively stressed human erythrocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987, 84: 7368-7372.

Wakui H, Imai H, Kobayashi R, Itoh H, Notoya T, Yoshida K, Nakamoto Y, Miura A: Autoantibody against erythrocyte protein 4.1 in a patient with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 1988, 72: 408-412.

Leddy JP, Falany JL, Kissel GE, Passador ST, Rosenfeld SI: Erythrocyte membrane proteins reactive with human (Warm-reacting) anti-red cell autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1993, 91: 1672-1680.

Franceschi LD, Fattovich G, Turrini F, Ayi K, Brugnara C, Manzato F, Noventa F, Stanzial AM, Solero P, Corrocher R: Hemolytic anemia induced by ribavirin therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Role of membrane oxidative damage. Hepatol. 2000, 31: 997-1004.

Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Yamabe H, Hart J, Bacchi CE, Hartwell P, Causer WG, Corey L, Wener MH, Alpers CE, Willson R: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Eng J Med. 1993, 328: 465-701. 10.1056/NEJM199302183280703.

Stehman-Breen C, Alpers CE, Causer WG, Willson R, Johnson RJ: Hepatitis C virus associated membranous glomerulonephritis. Clin Nephrol. 1995, 44: 141-147.

Ohsawa I, Ohi H, Tamano M, Endo M, Fujita T, Sotomura A, Hidaka M, Fuke Y, Matsushita M, Fujita T: Cryoprecipitate of patients with cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis contains molecules of the lectin complement pathway. Clin Immunol. 2001, 101: 59-66. 10.1006/clim.2001.5098.

Gournay J, Ferrell LD, Roberts JP, Ascher NL, Wright TL, Lake JR: Cryoglobulinemia presenting after liver transplamtation. Gastroenterol. 1996, 110: 265-270.

Ríos-Rull P, Rubio M, Ojeda E, Hemández Navarro F: Criøglobulinemia mixta esencial-hepatitis C positiva, anemia hemolytica autoimmune purpura thrombocitopenica immune. Sangre. 1994, 39: 225-

Emilia G, Luppin M, Ferrari MG, Borozzi P, Marasca R, Torelli G: Hepatitis C virus-induced leuko-thrombocytopenia and hemolysis. J Med Virol. 1997, 53: 182-184. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(19971003)53:2<182::AID-JMV12>3.0.CO;2-L.

Fellermann K, Stange E: Chronic hepatitis C, common variable immunodeficiency and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Coincidence by chance or common etiology?. Hepatogastroenterol. 2000, 47: 1422-1424.

Wei G, Yano S, Kuroiwa T, Hiromura K, Maezawa A: Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced IgG-IgM rheumatoid factor (RF) complex may be the main causal factor for cold-dependent activation of complement in patients with rheumatic disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997, 107: 83-88. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-882.x.

Dalekos GN, Kistis KG, Boumba DS, oulgari P, Zervou EK, Drosos AA, Tsianos EV: Increased incidence of anti-cardiolipin antibodies in patients with hepatitis C is not associated with aetiopathogenic link to anti-phospholipid syndrome. Eur J Gastoenterol hepat. 2000, 12: 67-74.

Ramos-Casals M, García-Carrasco M, López-Medrano F, Trejo O, Forns X, López-Guillermo A, Muñoz C, Ingelmo M, Font J: Severe autoimmune cytopenias in treatment-naive hepatitis C virus infection; Clinical description of 35 cases. Medicine. 2003, 82: 87-96. 10.1097/00005792-200303000-00003.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/4/7/prepub

Acknowledgements

Written consent to publish the details of his medical record was obtained from our patient prior to preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

IO, YU, and YF were participated in the medical treatment of our patient. SH carried out the serological studies, and cryoprecipitate analysis. ME performed the renal biopsy with help from IO. TF, HO, and YY performed the pathological analyses.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohsawa, I., Uehara, Y., Hashimoto, S. et al. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurred prior to evident nephropathy in a patient with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: case report. BMC Nephrol 4, 7 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-4-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-4-7