Abstract

Background

Accurate and precise estimates of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) are essential for clinical assessments, and many methods of estimation are available. We developed a radial basis function (RBF) network and assessed the performance of this method in the estimation of the GFRs of 207 patients with type-2 diabetes and CKD.

Methods

Standard GFR (sGFR) was determined by 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging and GFR was also estimated by the 6-variable MDRD equation and the 4-variable MDRD equation.

Results

Bland-Altman analysis indicated that estimates from the RBF network were more precise than those from the other two methods for some groups of patients. However, the median difference of RBF network estimates from sGFR was greater than those from the other two estimates, indicating greater bias. For patients with stage I/II CKD, the median absolute difference of the RBF network estimate from sGFR was significantly lower, and the P50 of the RBF network estimate (n = 56, 87.5%) was significantly higher than that of the MDRD-4 estimate (n = 49, 76.6%) (p < 0.0167), indicating that the RBF network estimate provided greater accuracy for these patients.

Conclusions

In patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus, estimation of GFR by our RBF network provided better precision and accuracy for some groups of patients than the estimation by the traditional MDRD equations. However, the RBF network estimates of GFR tended to have greater bias and higher than those indicated by sGFR determined by 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of end stage renal disease, a condition characterized by abnormal glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and serum creatinine (SCr) [1]. The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) considers GFR as the best overall measure of kidney function in healthy and diseased individuals [2]. However, measurement of GFR by use of radioisotopes is time-consuming and expensive, so this method is not used in routine clinical practice. Instead, numerous equations have been proposed to estimate the GFR without the need for radioisotopes [2]. These equations consider SCr and several additional variables, such as age, gender, race, and body size [2]. The American Diabetes Association [3] also recommends estimation of GFR from serum creatinine (SCr) -based formulae, such as a Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation [4].

However, these equations may yield inaccurate estimates in some populations, such as elderly Chinese patients with CKD [5]. Recent studies have criticized the equations currently used to estimate GFR in diabetic patients [6–10]. In particular, the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [6], the Mayo Clinic Quadratic (MCQ) equation [7], and the four-variable MDRD equation [8] all underestimated GFR in patients with type-2 diabetes, and the Cockcroft-Gault equation overestimated GFR in patients with type-2 diabetes [10]. These equations may be inaccurate because they do not account for ethnicity [11]. For example, in a group of Chinese patients with CKD, the MDRD equation 7 and the abbreviated MDRD equations underestimated GFR in patients with near-normal renal function and overestimated GFR in patients with advanced renal failure [12]. These equations may also be inaccurate because they were developed by linear regression methods [11, 13, 14]. Linear regression models do not account for the non-linear physiological processes that underlie GFR. Thus, it is important to develop better methodologies for estimation of GFR.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have been successfully used to model non-linear phenomena in the field of engineering forecasting. Modern ANNs provide effective nonlinear mapping of data, good fault tolerance, and good self-organization [15, 16]. Previous research demonstrated that an ANN was more accurate than a logistic regression model in prediction of clinical outcome in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and hemodynamic shock [17]. Other research groups have used ANNs to estimate GFR, including a knowledge-based neural network (KBNN) model [18], an evolving connectionist systems (ECOS) model [19], and a tree-based model with 6 terminal nodes [15]. In all of these cases, the ANNs provided better estimates of GFR than the traditional equations.

Radial basis function (RBF) networks are among the most widely used ANNs, but there have been limited clinical applications of these networks. Our previous study [20] described a simple RBF network for estimation of GFR (eGFRRBF) in a group of 327 Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The results indicated that the eGFRRBF had less bias and greater precision than the traditional MDRD equations. The accuracy (deviation less than 30% from the sGFR) of the eGFRRBF was significantly better than those from traditional eGFR equations, such as the Jelliffe-1973-equation and the Ruijin-equation [20].

In the present study, we tested the precision and accuracy of an RBF network model for estimation of GFR in an independent group of 207 Chinese patients who had type-2 diabetes and CKD and compared the results of the RBF network method with the results from two traditional MDRD formulae [13].

Methods

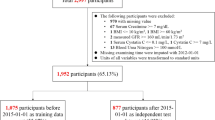

Patients

From January 2005 through December 2009, 207 consecutive patients with type-2 diabetes from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China) were enrolled. Patients younger than 18 years, taking cimetidine or trimethoprim, with acute kidney deterioration, clinical edema, skeletal muscle atrophy, pleural effusion or ascites, malnutrition, amputation, heart failure, or ketoacidosis were excluded. None of the patients were treated by dialysis during the study. CKD was staged according to the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) – Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines [2] based on the GFR measured by 99mTc-DTPA dynamic imaging method. Patients were placed into 3 groups based on CKD stage: (i) Stage I/II CKD (GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2); (ii) Stage III CKD (GFR = 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2); or (iii) Stage IV/V CKD (GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University and all patients provided informed consent. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measurements

GFR measured by the 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging method (modified Gate’s method) was used as the standard GFR (sGFR) [21, 22], and was calculated as described by Li et al. [23]. The gamma camera uptake method with 99mTc-DTPA is a simple method for determination of GFR, and is less time-consuming, and less expensive than other methods [24]. Moreover, this method has been recommended as the reference approach for determination of GFR by the Nephrology Committee of Society of Nuclear Medicine [25], and is widely used as a standard method for evaluation of kidney function and estimation of GFR in China. 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging was measured by a Millennium TMMPR SPECT using the General Electric Medical System, as described previously [22]. Serum albumin (Alb) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were assayed on a Hitachi 7180 autoanalyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan; reagents from Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). SCr was measured by an enzymatic method on the same instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SRM967 (standard reference material released by NIST for serum creatinine calibration) was used for calibration. Patient sex, age, height, and weight were recorded at the same time.

RBF network

An ANN is a computational method composed of interconnected artificial neurons (mathematical functions) that processes information and that typically consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. ANNs are used in diverse scientific and engineering fields to model the complex relationships of inputs and outputs. An RBF network is a feed-forward network with one hidden layer, in which activation of the hidden layer is a nonlinear radial basis function (a function whose value only depends on the distance to the origin).

In this study, the input layer consisted of measured serum creatinine (SCr) and the output layer consisted of sGFR. Our previous work [20] indicated that when SCr was measured by the enzymatic method, a simple RBF network model successfully estimated GFR in a population of 327 Chinese patients with CKD, based on analysis of all patients and on analysis of subgroups of patients with different stages of CKD [20]. In this previous study, the RBF network was a feed-forward ANN with an input layer of one unit (SCr), one hidden layer, and an output layer of one unit (sGFR), which was measured in all 327 CKD patients. This RBF network was constructed by use of the newrbe function in MathWorks. In the present study, we tested this RBF network in an independent group of 207 patients who had type-2 diabetes (external validation data set) to verify the original results.

MDRD equations

GFR was also estimated by the traditional MDRD equations [13]. In particular, we used the re-expressed 4-variable MDRD equation (R-MDRD4):

and the re-expressed 6-variable MDRD equation (R-MDRD6):

Statistical analysis

All demographic and clinical data are summarized as means ± standard deviations (SDs), as medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs: Q1, Q3) for continuous variables that had non-normal distributions, and as N and percent for categorical data (CKD stage). Data were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc correction, the Kruskall Wallis test, the Mann–Whitney U test for pair-wise comparisons of data that had non-normal distributions, or Pearson’s Chi-square test (gender).

The overall differences between eGFR and sGFR are summarized as medians and IQRs due to the non-normal distributions. Differences among patients with different CKD stages were compared with the Kruskall Wallis test with a post hoc method or with the Mann–Whitney U test for pair-wise comparisons. Within-group comparisons of measurements were performed using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test for a given CKD stage.

The accuracy of eGFR are summarized as N and percent of patients with eGFR differing less than 15% (P15), 30% (P30), and 50% (P50) from sGFR. Accuracy of the estimates was compared for patients with different CKD stages using the Pearson Chi-square test. The accuracies of eGFR values were compared using the McNemar test within the same CKD stage. Bland-Altman plots (eGFR4 vs. sGFR, eGFR6 vs. sGFR, and eGFRRBF vs. sGFR) were graphed with Medcalc for Windows (ver. 9.3.9.0, Mariekerke, Belgium). The 3 different methods of estimating GFR were also used to classify patients by CKD stage. A Wilcoxon sign-rank test was used to compare the differences of CKD stages from sGFR and each of these estimates.

All statistical assessments were two-tailed and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The significance level was adjusted by Bonferroni’s method to 0.0167 (0.05/3) and 0.01 (0.05/4) for post hoc pair-wise comparisons of CKD stages and eGFR, respectively. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 11.0 SPSS, Chicago IL, USA).

Results

A total of 207 patients (119 males, 88 females) with a mean age of 61.43 years (SD = 12.03) were enrolled. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 207 patients and of sub-groups with different stages of CKD. There were 64 patients (30.9%) with stage I/II disease, 81 patients (39.1%) with stage III disease, and 62 patients (30%) with stage IV/V disease. As expected, patients with more severe disease had lower serum Alb and sGFR, and higher SCr and BUN (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the sGFR values and the three different estimates of GFR (eGFR4, eGFR6, and eGFRRBF) for all 207 patients and for sub-groups with different stages of CKD. As expected, GFR values were lower in patients with more advanced disease. The eGFRRBF of all 207 CKD patients and of patients with different stages of CKD were significantly higher than the sGFR values (p < 0.01 for all). In addition, for patients with stage III or stage IV/V CKD, the eGFRRBF values were significantly higher than those from eGFR4 and eGFR6 (p < 0.01 for both).

The validity of an estimate is a function of its accuracy and precision, and a valid estimate should be close to the true value (low bias) and be reproducible [26]. Table 3 presents the overall performances of the 3 different estimates of GFR in all 207 patients and in patients with different stages of CKD. Each row in the table shows the median difference of eGFR and sGFR and the inter-quartile range (IQR), the median absolute difference of eGFR and sGFR and the IQR, and the percent of GFR estimates within 15% (P15), 30% (P30), and 50% (P50) of sGFR [26]. The results indicate that for all 207 patients, the IQR of the eGFRRBF was smaller than those from eGFR4 and eGFR6, indicating better precision for the RBF network; however, the median difference of the eGFRRBF from sGFR was significantly higher than those from eGFR4 and eGFR6 (p < 0.0167 for both). The same trends occurred in patients with stage III CKD and stage IV/V CKD. The eGFRRBF had a lower median absolute difference from sGFR and a higher percent of estimates within 15% (P15) and 30% (P30) of sGFR, suggesting that eGFRRBF had better accuracy. However, the differences between eGFRRBF and eGFR4 and eGFR6 were not statistically different. The results also indicate that for the patients with stage I/II CKD, the median absolute difference of eGFRRBF and sGFR (19.73) was significantly less than that of eGFR4 and sGFR (27.28) (p < 0.0167), although the P50 for eGFRRBF (n = 56, 87.5%) was significantly higher than that for eGFR4 (n = 49, 76.6%) (p < 0.0167).

Figure 1 shows Bland-Altman plots for comparisons of sGFR with GFR estimated by eGFR4 (A), eGFR6 (B), and eGFRRBF (C). The precision is indicated by the distance between the dashed lines (95% limits of agreement) [27]. The results indicate that the distance between lines of 95% limits of agreement was 71.4 for eGFRRBF, significantly lower than that for eGFR4 (91.5) and eGFR6 (85.2). Thus, this analysis also indicates that the eGFRRBF had better precision than the two other estimates from the MDRD equations. However, Figure 1 also shows that the mean differences of sGFR and eGFR4 was 3.1, sGFR and eGFR6 was 1.0, and sGFR and eGFRRBF was 11.1. This indicates that eGFRRBF had greater bias than the estimates from the MDRD equations and over-estimate the GFR.

Bland-Altman plots of the estimation of GFR (mL/min/1.73 m 2 ) relative to sGFR by the (A) re-expressed 4-variable MDRD equation (eGFR 4 ), (B) re-expressed 6-variable MDRD equation (eGFR 6 ), and (C) RBF network (eGFR RBF ). Solid lines represent mean differences and dashed lines represent 95% limits of agreement of the mean difference.

Discussion

We compared the performance of an RBF neural network in the estimation of GFR with the performance of two traditional GFR estimates based on the MDRD equations (MDRD-4 and MDRD-6) in patients with type-2 diabetes and different stages of CKD. Our results indicate that the RBF network provided more precise estimates of GFR than the MDRD equations, and also provided significantly more accurate estimates of GFR for patients with stage I/II CKD. However, the RBF network also had higher bias than the traditional MDRD equations. In particular, the eGFRRBF tended to over-estimate GFR more than eGFR4 and eGFR6, especially for patients with CKD stage IV/V (Table 2).

In the field of medical data processing, the theoretical basis for the use of statistical regression methods is the “law of large numbers”. That is, the difference of the average of many measurements from the true value should be smaller as more measurements are recorded. However, application of a model derived from one data set to another data set may yield poorer accuracy. Moreover, regression methods can only be used for a limited number of models, and interactions among variables places limits on their use. ANNs have no a priori requirement for data distribution, and can handle multi-collinear input variables, neither of which can be managed by regression methods.

These advantages of ANNs have led to their use in several previous studies for estimation of GFR. Song et al. [18] used a knowledge-based neural network model (KBNN) for evaluation of renal function based on 441 GFR data vectors from 141 patients. Their proposed GFR prediction model had at least 10% better accuracy than any of the individual regression formulae or a standard neural network model. Marshall et al. [19] used evolving connectionist systems (ECOS), in which computing structures are trained to generate output from a given set of input variables. They concluded that their ECOS model provided better prediction of GFR in routine clinical practice. No ANNs have been used to estimate GFR of patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus.

It is noteworthy that the RBF network used in this study was only based on SCr measurements, in contrast to the re-expressed MDRD equations, which require measurement of 4 or 6 variables. The NKF does not recommend use of SCr alone for assessment of kidney function [2]. However, previous research indicated that use of fewer variables can yield acceptable estimates of GFR. For example, Bevc et al. [28] reported that a cystatin C-based estimate, which only requires measurement of serum cystatin C, is a reliable marker of GFR in elderly patients and is comparable to the creatinine-based formulae, including the CKD-EPI formulae. Our results suggest that an RBF model based on a single measurement (SCr) can provide precise and accurate estimates of GFR.

There are several limitations to our study. First, SCr was measured by the enzymatic method. Peake et al. [29] indicated that the enzymatic creatinine assay, although theoretically more specific, can have interference problems. However, this method produces results for patient samples that agree closely with the results from isotope dilution mass spectrometry (ID-MS). This motivated our use of the re-expressed MDRD equations (MDRD-4 and MDRD-6) instead of the original equation [4], because the original MDRD equation was developed for use with ID-MS traceable serum creatinine [30]. Second, ANN models can be difficult to display as equations and cannot be readily used without special software, so physicians may be reluctant to accept the results of ANN models. There is need for a platform that can display ANN models and that allows other researchers to readily perform external validation. Third, a previous study-indicated that GFR estimated by 99mTc-DTPA dynamic renal imaging might not better than the modified abbreviated MDRD equation [31], and the renal dynamic imaging method was less accurate than CKD-EPI equation as well [32]. However, the same study found that the two methods performed similar capability in determining GFR among higher-GFR patients [32], and 99mTc-DTPA dynamic renal dynamic imaging yields accurate results that are nearly the same as those from measurements of inulin clearance [33]. Rehling et al. showed that a regression line between the values measured by these different methods did not differ from the line of identity [33]. Ma et al. (2007) suggested that, using proper reference GFR, more adequate background subtraction, and soft-tissue attenuation correction may improve the accuracy of 99mTc-DTPA dynamic renal imaging [31]. Finally, our RBF network predicted a higher GFR than that from 99mTc- DTPA renal dynamic imaging. This might be due to differences of participants in the training group (CKD patients with and without diabetes [20]) and the study group (diabetes patients with and without normal kidney function). Use of more similar training and study groups would provide better external validation and may provide improved results.

A recent survey in China [34] showed that the prevalence of diabetes was 9.7%, corresponding to 92.4 million people. Although some of the established methods used to estimate GFR are suitable for Chinese patients with CKD [22], it is important to have more accurate and precise estimations of GFR. In some measures of accuracy and precision, our RBF neural network performed significantly better than the re-expressed MDRD equations in the estimation of GFR. In particular, the IQRs (Table 3) and 95% limits of agreement (Figure 1) for the eGFRRBF were smaller than those from eGFR4 and eGFR6, indicating better precision for the RBF network. However, our data indicated that eGFR estimated by the RBF neural network tended to be higher than the sGFR, and this would result in under-estimation of CKD stage. We suggest that use of an RBF network model with more variables and testing of the model with additional data sets may ultimately provide more accurate and precise estimates of GFR.

Conclusions

In patients with type-2 diabetes, GFR estimated by our RBF network provided better precision and accuracy for some groups of patients than GFR estimated by the traditional MDRD equations. However, the RBF network estimates of GFR tended to have greater bias and higher than those indicated by sGFR determined by 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging.

References

Barnett AH: Preventing renal complications in diabetic patients: the Diabetics Exposed to Telmisartan And enalaprIL (DETAIL) study. Acta Diabetol. 2005, 42: S42-S49. 10.1007/s00592-005-0180-4.

National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002, 39: S1-266.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2012. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35: S11-S63.

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999, 130: 461-470. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002.

Liu X, Wang C, Tang H: Assessing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD): A comparison of various predictive equations. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010, 51: 13-20. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.06.005.

Silveiro SP, Araújo GN, Ferreira MN, Souza FD, Yamaguchi HM, Camargo EG: Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation pronouncedly underestimates glomerular filtration rate in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34: 2353-2355. 10.2337/dc11-1282.

Fontseré N, Bonal J, Salinas I, de Arellano MR, Rios J, Torres F, Sanmartí A, Romero R: Is the new Mayo Clinic Quadratic equation useful for the estimation of glomerular filtration rate in type 2 diabetic patients?. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31: 2265-2267. 10.2337/dc08-0958.

Nair S, Mishra V, Hayden K, Lisboa PJ, Pandya B, Vinjamuri S, Hardy KJ, Wilding JP: The four-variable modification of diet in renal disease formula underestimates glomerular filtration rate in obese type 2 diabetic individuals with chronic kidney disease. Diabetologia. 2011, 54: 1304-1307. 10.1007/s00125-011-2085-9.

Joshy G, Porter T, Le Lievre C, Lane J, Williams M, Lawrenson R: Implication of using estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in a multi ethnic population of diabetes patients in general practice. N Z Med J. 2010, 123: 9-18.

Rigalleau V, Beauvieux MC, Le Moigne F, Lasseur C, Chauveau P, Raffaitin C, Perlemoine C, Barthe N, Combe C, Gin H: Cystatin C improves the diagnosis and stratification of chronic kidney disease, and the estimation of glomerular filtration rate in diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2008, 34: 482-489. 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.03.004.

Stevens LA, Claybon MA, Schmid CH, Chen J, Horio M, Imai E, Nelson RG, Van Deventer M, Wang HY, Zuo L, Zhang YL, Levey AS: Evaluation of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation for estimating the glomerular filtration rate in multiple ethnicities. Kidney Int. 2011, 79: 555-562. 10.1038/ki.2010.462.

Zuo L, Ma YC, Zhou YH, Wang M, Xu GB, Wang HY: Application of GFR-estimating equations in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005, 45: 463-472. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.11.012.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F: Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006, 145: 247-254. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH: CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 150: 604-612. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006.

Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Pappas L: Prediction of renal insufficiency in Pima Indians with nephropathy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002, 40: 252-264. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34503.

Baxt WG, Skora J: Prospective validation of artificial neural network trained to identify acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1996, 347: 12-15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91555-X.

Dybowski R, Weller P, Chang R, Gant V: Prediction of outcome in critically ill patients using artificial neural network synthesised by genetic algorithm. Lancet. 1996, 347: 1146-1150. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90609-1.

Song Q, Kasabov N, Ma T, Marshall MR: Integrating regression formulas and kernel functions into locally adaptive knowledge-based neural networks: a case study on renal function evaluation. Artif Intell Med. 2006, 36: 235-244. 10.1016/j.artmed.2005.07.007.

Marshall MR, Song Q, Ma TM, MacDonell SG, Kasabov NK: Evolving connectionist system versus algebraic formulas for prediction of renal function from serum creatinine. Kidney Int. 2005, 67: 1944-1954. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00293.x.

Liu X, Wu XM, Li LS, Lou TQ: Application of radial basis function neural network to estimate glomerular filtration rate in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. ICCASM. 2010, 15: 332-335. [The International Conference on Computer Application and System Modeling]

Du X, Liu L, Hu B, Wang F, Wan X, Jiang L, Zhang R, Cao C: Is the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration four-level race equation better than the cystatin C equation?. Nephrology (Carlton). 2012, 17: 407-414. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01568.x.

Liu X, Lv L, Wang C, Shi C, Cheng C, Tang H, Chen Z, Ye Z, Lou T: Comparison of prediction equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. Intern Med J. 2012, 42: e59-67. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02398.x.

Li Q, Zhang CL, Fu ZL, Wang RF, Ma YC, Zuo L: Development of formulae for accurate measurement of the glomerular filtration rate by renal dynamic imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 2007, 28: 407-413. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3280a02f8b.

Assadi M, Eftekhari M, Hozhabrosadati M, Saghari M, Ebrahimi A, Nabipour I, Abbasi MZ, Moshtaghi D, Abbaszadeh M, Assadi S: Comparison of methods for determination of glomerular filtration rate: low and high-dose Tc-99m-DTPA renography, predicted creatinine clearance method, and plasma sample method. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008, 40: 1059-1065. 10.1007/s11255-008-9446-4.

Blaufox MD, Aurell M, Bubeck B, Fommei E, Piepsz A, Russell C, Taylor A, Thomsen HS, Volterrani D: Report of the Radionuclides in Nephrourology Committee on renal clearance. J Nucl Med. 1996, 37: 1883-1890.

Stevens LA, Zhang Y, Schmid CH: Evaluating the performance of equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate. J Nephrol. 2008, 21: 797-807.

Bland JM, Altman DG: Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986, 1: 307-310.

Bevc S, Hojs R, Ekart R, Gorenjak M, Puklavec L: Simple cystatin C formula compared to sophisticated CKD-EPI formulas for estimation of glomerular filtration rate in the elderly. Ther Apher Dial. 2011, 15: 261-268. 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.00948.x.

Peake M, Whiting M: Measurement of serum creatinine– current status and future goals. Clin Biochem Rev. 2006, 27: 173-184.

Hallan S, Astor B, Lydersen S: Estimating glomerular filtration rate in the general population: the second Health Survey of Nord-Trondelag (HUNT II). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006, 21: 1525-1533. 10.1093/ndt/gfl035.

Ma YC, Zuo L, Zhang CL, Wang M, Wang RF, Wang HY: Comparison of 99mTc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging with modified MDRD equation for glomerular filtration rate estimation in Chinese patients in different stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007, 22: 417-23.

Xie P, Huang JM, Liu XM, Wu WJ, Pan LP, Lin HY: (99m)Tc-DTPA renal dynamic imaging method may be unsuitable to be used as the reference method in investigating the validity of CKD-EPI equation for determining glomerular filtration rate. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e62328-10.1371/journal.pone.0062328.

Rehling M, Møller ML, Thamdrup B, Lund JO, Trap-Jensen J: Reliability of a 99mTc-DTPA gamma camera technique for determination of single kidney glomerular filtration rate. A comparison to plasma clearance of 51Cr-EDTA in one-kidney patients, using the renal clearance of inulin as a reference. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1986, 20: 57-62. 10.3109/00365598609024481.

Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, Jia W, Ji L, Xiao J, Shan Z, Liu J, Tian H, Ji Q, Zhu D, Ge J, Lin L, Chen L, Guo X, Zhao Z, Li Q, Zhou Z, Shan G, He J, China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study Group: Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362: 1090-1101. 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/14/181/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients for their cooperation.

Sources of support

This work were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81370866 and 81070612), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 201104335), the Guangdong Science and Technology Plan (Grant No. 2011B031800084), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 11ykpy38) and the National Project of Scientific and Technical Supporting Programs Funded by Ministry of Science & Technology of China (Grant No. 2011BAI10B05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XL, TQ-L: planning of the project; XL, YR-C CW and ML: carrying out of the experimental work; XL, NS-Li, LS-Lv and XM-W: intellectual analysis of the data; XL: writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Xun Liu, Yan-Ru Chen, Ning-shan Li contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Chen, YR., Li, Ns. et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by a radial basis function neural network in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Nephrol 14, 181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-181

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-181