Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is more prevalent in Taiwan than in most countries. This population-based cohort study evaluated the dementia risk associated with CKD.

Methods

Using claims data of 1,000,000 insured residents covered in the universal health insurance of Taiwan, we selected 37049 adults with CKD newly diagnosed from 2000–2006 as the CKD cohort. We also randomly selected 74098 persons free from CKD and other kidney diseases, frequency matched with age, sex and the date of CKD diagnosed. Incidence and hazard ratios (HRs) of dementia were evaluated by the end of 2009.

Results

Subjects in the CKD cohort were more prevalent with comorbidities than those in the non-CKD cohort (p <0.0001). The dementia incidence was higher in the CKD cohort than in the non-CKD cohort (9.30 vs. 5.55 per 1,000 person-years), with an overall HR of 1.41 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.32-1.50), controlling for sex, age, comorbidities and medicaitions. The risk was similar in men and women but increased sharply with age to an HR of 133 (95% CI, 68.9-256) for the elderly. However, the age-specific CKD cohort to non-CKD cohort incidence rate ratio decreased with age, with the highest ratio of 16.0 (95% CI, 2.00-128) in the youngest group. Among comorbidities and medications, alcoholism and taking benzodiazepines were also associated with dementia with elevated adjusted HRs of 3.05 (95% CI 2.17-4.28) and 1.23 (95% CI 1.14-1.32), respectively.

Conclusions

Patients with CKD could have an elevated dementia risk. CKD patients with comorbidity deserve attention to prevent dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among all countries, the incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (41.5 per 100,000) has been the highest in Taiwan since 2000 [1–4]. There were more than 2 million ESRD patients worldwide in 2010 requiring dialysis or transplantation [5]. It is well known that patients with diabetes mellitus and/or chronic kidney disease are at high risk of developing ESRD [3–7]. The prevalence of CKD has been shown to be higher in older adults in Taiwan [2], United States [6], Japan [7] and internationally [8, 9].

Dementia is a heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder, including vascular-type dementia and Alzheimer-type dementia [10]. The prevalence of dementia increases with age, from less than 1% in people aged 65 years to more than 25% in those aged 85 years or over [11, 12]. Dementia has been a hidden health issue in Taiwan in the elderly population. The prevalence of the disorder in the elderly in Taiwan increased continuously over past decades, from 4.1% in 1980, to 6.1% in 1990, to 8.6% in 2000 and to 10.2% in 2007 [13]. It is therefore important to identify protective and risk factors for dementia to prevent this disease at an early stage. CKD has been proposed as a major factor of developing ESRD. It is also an independent risk factor for cognitive impairment but with conflicting findings among studies. Dementia and CKD have been recognized as comorbidities with higher incidence rate among the elderly [10], Sasaki et al. further found the incidence rate of dementia in Osaki area patients with CKD was much higher than the general Japanese population (24.0% vs. 9.0%) [14].

Recent studies in the US have also shown that impaired kidney function is associated with the increased prevalence of cognitive impairment [15, 16]. Studies have identified age, hypertension and diabetes mellitus as independent factors in the association between kidney function and impaired cognition [14–17]. However, there were limited population based cohort studies on the association between CKD and the risk of dementia. To fill this research gap, we conducted this population based cohort study using claims data from the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan to explore issues of (i) the association between CKD and dementia in the aging population in Taiwan, (ii) the role of other comorbidities in the risk of dementia, (iii) the relationship between medications and the risk of dementia.

Methods and materials

Data sources

The National Health Insurance (NHI) of Taiwan is a universal health insurance program reformed in 1995, offers the coverage to 99% of the nation’s population of 23 million, and approximately 97% of hospitals and clinics have contracted with the NHI [18]. For research and administrative purposes, the National Health Research Institute, Taiwan, has used the claims data to establish various sets of database for public uses. This study used a longitudinal dataset including one-million insured people randomly selected from the whole population covered by the NHI. This dataset contains information on all medical services, such as ambulatory care claims, inpatient claims and prescription drugs and registry beneficiaries [18–20]. The privacy of all patients was protected by the encryption of personal identification. Using the unique scrambled personal identifications, we were able to link these to obtain medical histories and demographic variables. This study was exempted from full institutional review.

Study subjects

In this study, we identified study subjects from 2000 to 2006 with newly diagnosed chronic kidney disease (CKD) as CKD cohort and those without any CKD diagnosis as non-CKD cohort. Subjects in the CKD cohort were identified using International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], including 250.4(diabetes with renal manifestations), 274.1(gouty nephropathy), 403(hypertensive chronic kidney disease)- 404(hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease), 440.1(disease of renal artery), 442.1(disease of renal artery), 447.3(hyperplasia of renal artery), 581(nephritic syndrome)-583(nephritis and nephropathy), 585(chronic renal failure)-588(disorders resulting from impaired renal function). Inpatients with at least one CKD diagnosis or outpatients with twice CKD service claims were included in the CKD cohort. Patients with codes of 283.1(hemolytic uremic syndrome), 572.4 (hepatorenal syndrome), 642.1(Hypertension secondary to renal disease, complicating pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium) and 646.2(Unspecified renal disease in pregnancy, without mention of hypertension) were excluded. Patients who had diagnoses of ESRD, renal transplantation therapy or dialysis therapy were also excluded. The first date of diagnosed CKD was the index date for the follow-up time measure. Subjects with dementia (ICD-9-CM 290.0, 290.1, 290.2, 290.3, 290.4, 294.1 and 331.0) prior to the index date or with missing information on gender or age were also excluded from this study.

For each CKD patient, two non-CKD subjects were randomly selected frequency matching with gender, age (every 5 years), index-year and index-month. The exclusion criteria used to select CKD cohort were used to select non-CKD cohort. We also avoid selecting subjects developing CKD in the non-CKD cohort, during the follow-up period. The follow-up time in person-years was calculated for each study subject until the occurrence of dementia, the end of 2009 or censored because of deaths or withdrawal from the insurance program. Other considered comorbidities at the baseline were hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401–405, A-code A260 and A269), diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM 250 and A-code A181), ischemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM 410–414, A-code A270 and A279), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM 272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.3 and 272.4), tobacco use disorder (ICD-9-CM 305.1), alcoholism (ICD-9-CM 291, 291.2, 291.9, 303.9, 334.4, 980.0, V11.3, V79.1 and V61.41), morbid obesity (ICD-9-CM 278.0, 278.00, 278.01, 649.1, 783.1 and V77.8), atrial fibrillation (ICD-9-CM ), Parkinson's disease (ICD-9-CM 332 and A-code A221), cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9-CM 430–438, A-code A290-A294 and A299), major depressive disorder (ICD-9-CM 296.2 and 296.3), and elevated C-reactive protein screen (ICD-9-CM 790.95). The analysis of medication drugs related to dementia was performed for the use of benzodiazepine, aspirin, other NSAIDs and COX2.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis first compared the demographic status and comorbidites between CKD and non-CKD cohorts. The Chi-square test was used to compare the difference in gender, age and baseline comorbidities between the CKD and non-CKD cohorts. Student’s t-test was used to compare the difference in mean age. Incidence rates of dementia for both cohorts, and the CKD cohort to non-CKD cohort incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated by gender, age and follow-up time (< 2 and ≥ 2 years). We estimated incidence rates of dementia by comorbidity and medication, and used Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the specific hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals of dementia for the CKD cohort compared to the non-CKD cohort. The Cox model was also used to estimate age, sex, comorbidity and medication specific crude HRs of dementia and the multivariate adjusted HRs. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and the statistical significance level was set at two-sided p < 0.05.

Results

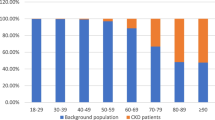

There were more men than women in both cohorts (54.2% vs. 45.8%), with the mean age slightly greater in the CKD cohort than the non-CKD cohort (Table 1). Approximately 15% of subjects were young in 20–39 years of age. Subjects with CKD had a higher prevalence of all baseline comorbidities and medications (p < 0.0001). Table 2 shows that the incidence of dementia was higher in the CKD cohort than in the non-CKD cohort (9.30 vs. 5.55 per 1,000 person-years), with an IRR of 1.68 (95% CI 1.58-1.78). The incidence was slightly higher in women than in men, increased with age. But the age-specific relative risk was the highest for the youngest subcohort with an IRR of 16.0 (95% CI 2.00-128.0), and the lowest for the elderly with the IRR of 1.75 (95% CI 1.64-1.86). The IRR declined slightly after a 2-year follow-up.

Table 3 presents the comorbidity-specific incidence rates of dementia in both cohorts and the CKD cohort to non-CKD cohort hazard ratios after controlling for age, sex, and medications. Most of comorbidities are associated with increased dementia incidence, the highest for CKD patients with the comorbidity of Parkinson's disease (50.9 per 1,000 person-years), followed by those with atrial fibrillation (29.9 per 1,000 person-years), cerebralvascular disease (25.1 per1,000 person-years), etc. These comorbidites were also associated with increased dementia incidence for non-CKD subjects.

The CKD cohort had a higher risk of dementia than the non-CKD cohort (adjusted HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.32-1.50) in the multivariate Cox model (Table 4). There was no significant different in the dementia risk between men and women. The adjusted hazard of dementia was much greater for the elderly (HR 133.0, 95% CI 68.9-256), compared with those in 20–39 years of age. CKD patients with the comorbidity of Parkinson's disease had a crude HR of 6.92 (95% CI 6.13-7.82), compared with the non-CKD cohort. The risk remained significant (HR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.59-2.04) in the multivariate analysis. However, the HR in the multivariable model was the highest for patients with alcoholism (HR = 3.05, 95% CI 2.17-4.28). Some other comorbidities could also predict the elevated hazard of dementia for patients with CKD, except for ischemic heart disease, hyperlipidemia, obesity, atrial fibrillation and the use of aspirin and other NSAIDs. The crude HR associated with hyperlipidemia was significant, but became protective in the multivariable analysis. Taking benzodiazepines were also associated with the dementia risk.

Discussion

This study revealed that the risk of dementia in the CKD cohort was higher than that in the non-CKD cohort yield a HR of 1.04 after controlling for demographic variables and medical conditions. This result is comparable with the findings in previous studies. Nickolas et al. found that the mild cognitive impairment in older adults with CKD is also a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia [21]. Another survey revealed that moderate to severe CKD in stroke-free subjects was associated with white matter hyperintensity, which is resulted from inflammation and endothelial dysfunction and is a risk for dementia [22, 23]. In addition, the present study supports previous findings of the relationship between impaired kidney function and cognitive decline [16, 17, 22, 24–26]. Kahtri et al found that patients with kidney disease even with mild CKD 訂 e at an elevated risk of cognitive impairment [24].

It is important to note that a large proportion of CKD patients were young, aged 20-39 years, accounting for approximately 15% in the cohort. The young CKD patients to the young non- CKD patients IRR of dementia was near 9-fold greater than that for the elderly, reflecting CKD has a strong impact for young people. The corresponding IRR for 40-64 years was 13.6-fold greater than the elderly. Our data also showed that the risk of dementia declined with longer follow-up time, indicating dementia may develop in earlier period of CKD. Prevention care should be started earlier period including younger CKD patients.

This study also found several comorbidities and medications could predict dementia. The associations between blood pressure, diabetes and dementia and cognitive impairment have received much attention in studies, but the results are somewhat in conflict [25–32]. High blood pressure increases the risk of dementia in the elderly [26, 30]. Xu et al. found that the risk of dementia was especially high for patients with diabetes mellitus and severe systolic hypertension [30]. Our results echo most of previous findings that hypertension and diabetes are independent predictors of dementia [32].

An earlier study has found that very old women with myocardial infarction are 5-time more likely prone to dementia than those without the disease [33]. The cross-sectional analysis from the Rotterdam study showed that the prevalence of dementia was increased with the degree of peripheral arterial atherosclerotic disease. The odds ratio for cognitive decline in those with severe atherosclerosis was 3:0 [34]. Our study showed that CKD patients with ischemic heart disease were 2.8-fold (17.0 vs. 6.05 per 1000 person-years) more likely than CKD patients without the comorbidity for the risk of dementia. This association became insignificant in the multivariate analysis.

Among comorbidities, alcoholism has the strongest association with dementia in this study. Breteler found a significant relationship between alcohol intake and the risk of vascular disease [35]. Those with moderate alcohol intake may not at an increased risk of dementia [36–38]. The congnitive impairment due to alcohol addition has been 臼 ported as alcohol dementia [29, 39]. Alcoholism was less prevalent in our study population,but it is an important risk factor of dementia.

In addition to alcoholism, hypertension and diabetes, we also found that cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson's disease and major depressive disorder were significant comorbidities associated with dementia. Studies have reported cerebrovascular disease as a major contributor to later-life dementia [31, 40–44]. Our findings reiterate previous pathological investigations. The later epidemiological studies may have raised the possibility that cerebrovascular disease and dementia are two disorders causally related [42]. Parkinson's disease and the major depressive disorder are relatively less important than cerebrovascular disease in the association with the dementia risk [45–47].

Hyperlipidemia had a significant risk of dementia in the univariate model but it became a protective effect after being adjusted. In subjects without hyperlipidemia, the incidence of dementia in CKD patients is higher than non-CKD patients (9.36 vs. 5.33 per 1,000 person-years). However ,the incidence in CKD patients with hyperlipidemia declined to 9.14 per 1,000 person-years. The association between hyperlipidemia and dementia is not clear. The colinearity of hypertension and hyperlipidemia may explain the phenomenon.

The significant relation between dementia and medications of benzodiazepines agents and aspirin is another important finding in this study. Previous studies have reported that the long-term use of benzodiazepines agents is responsible for moderate-to-large weighted risk of dementia [48–52]. The aspirin use might pose an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhages [53]. It is not clear whether this is the mechanism increases the risk of dementia.

Limitations

The insurance claims data provided no measures of serum creatinine and microalbuminuria, and we were unable to evaluate the dementia risk based on kidney function. CKD patients at an earlier stage might not be included in the study. This may, therefore, have resulted in estimating the risk for patients with more severe condition of CKD. Second, as diagnosis of CKD and dementia requires long-term observation for clinical manifestation, the seven-year or less observation period in this study may be insufficient to estimate the dementia risk with the full course of natural history. The associated risk measures may be thus underestimated.

Third, this study included conmorbidity information at the baseline, prior to the date of establishing the study cohorts. Comorbidities developed during the follow-up period may vary and the estimation of dementia risk may vary.

Conclusions

This study evaluated the risk of dementia in associations with CKD and several medical conditions and medications for the Asian population, using representative population-based data. We have demonstrated that patients with CKD are at a significantly higher risk of dementia than those without CKD. Other comorbidity may also interact with CKD and increase further the risk of dementia. CKD is a much more prevalent disorder in the current study population than populations of many other countries. Studies are needed for patients with CKD not only for the prevention of developing end stage renal disease, but also for preventing the progression of dementia. The identification of comorbidities and medications may yield important prevention opportunity for reducing dementia development. Our data suggest that intervention should be applied to young patients as well.

References

Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC: Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan. Nephrology (Carlton). 2010, 15 (Suppl 2): 3-9.

Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, Yang CY: Epidemiological features of CKD in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007, 49 (1): 46-55. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.10.007.

Collins AJ, Kasiske B, Herzog C, Chavers B, Foley R, Gilbertson D, et al: Excerpts from the United States Renal Data System 2004 annual data report:atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005, 45 (Suppl 1): 5-7.

Abbasi M, Chertow G, Hall Y: End-stage Renal Disease. Am Fam Physician. 2010, 82 (12): 1512-

Xue JL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Collins AJ: Forecast of the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001, 12 (12): 2753-2758.

Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007, 298 (17): 038-2047.

Imai E, Horio M, Iseki K, Yamagata K, Watanabe T, Hara S, et al: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the Japanese general population predicted by the MDRD equation modified by a Japanese coefficient. Clin Exp Nephro. 2007, 11 (2): 156-163. 10.1007/s10157-007-0463-x.

Hsu CC, Hwang SJ, Wen CP, Chang HY, Chen T, Shiu RS, Horng SS, Chang YK, Yang WC: High prevalence and low awareness of CKD in Taiwan: a study on the relationship between serum creatinine and awareness from a nationally representative survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006, 48 (5): 727-738. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.018.

Zhang QL, Rothenbacher D: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in population-based studies: systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 117-129. 10.1186/1471-2458-8-117.

Seliger SL, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen CO, Gillen DL, Fitzpatrick A, Bleyer A, Kuller LH: Moderate renal impairment and risk of dementia among older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004, 15 (7): 1904-1911. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000131529.60019.FA.

Frolich L, Blum-Degen D, Bernstein HG, Engelsberger S, Humrich J, Laufer S, Muschner D, Thalheimer A, Turk A, Hoyer S, et al: Brain insulin and insulin receptors in aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm. 1998, 105 (4–5): 423-438.

Ott A, Slooter AJ, Hofman A, van Harskamp F, Witteman JC, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM: Smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in a population-based cohort study: the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1998, 351 (9119): 1840-1843. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07541-7.

Fuh JL, Wang SJ: Dementia in Taiwan: past, present, and future. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2008, 17 (3): 153-161.

Sasaki Y, Marioni R, Kasai M, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S, Meguro K: Chronic kidney disease: a risk factor for dementia onset: a population-based study. The Osaki-Tajiri Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011, 59 (7): 1175-1181. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03477.x.

Kurella Tamura M, Wadley V, Yaffe K, McClure LA, Howard G, Go R, Allman RM, Warnock DG, McClellan W: Kidney function and cognitive impairment in US adults: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008, 52 (2): 227-234. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.004.

Yaffe K, Ackerson L, Kurella Tamura M, Le Blanc P, Kusek JW, Sehgal AR, Cohen D, Anderson C, Appel L, Desalvo K, et al: Chronic kidney disease and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort cognitive study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010, 58 (2): 338-345. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02670.x.

Weng SC, Shu KH, Tang YJ, Sheu WH, Tarng DC, Wu MJ, et al: Progression of cognitive dysfunction in elderly chronic kidney disease patients in a veteran's institution in central Taiwan: a 3-year longitudinal study. Intern Med. 2012, 51 (1): 29-35. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.5975.

Lai SW, Liao KF, Liao CC, Muo CH, Liu CS, Sung FC: Polypharmacy correlates with increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly: a population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010, 89 (5): 295-299. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181f15efc.

Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, Sung FC, Chen PC: Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011, 106 (9): 1697-1704. 10.1038/ajg.2011.155.

Lai SW, Su LT, Lin CH, Tsai CH, Sung FC, Hsieh DP: Polypharmacy increases the risk of Parkinson's disease in older people in Taiwan: a population-based study. Psychogeriatrics. 2011, 11 (3): 150-156. 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00369.x.

Nickolas TL, Khatri M, Boden-Albala B, Kiryluk K, Luo X, Gervasi-Franklin P, Paik M, Sacco RL: The association between kidney disease and cardiovascular risk in a multiethnic cohort: findings from the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS). Stroke. 2008, 39 (10): 2876-2879. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513713.

Khatri M, Wright CB, Nickolas TL, Yoshita M, Paik MC, Kranwinkel G, Sacco RL, DeCarli C: Chronic kidney disease is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume: the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS). Stroke. 2007, 38 (12): 3121-3126. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493593.

Vliet PV: Cholesterol and Late-Life Cognitive Decline. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 30: S147-S162.

Khatri M, Nickolas T, Moon YP, Paik MC, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, Wright CB: CKD associates with cognitive decline. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009, 20 (11): 2427-2432. 10.1681/ASN.2008101090.

Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L: The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4 (8): 487-499. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1.

Skoog I, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, Palmertz B, Andreasson LA, Nilsson L, Persson G, Oden A, Svanborg A: 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet. 1996, 347 (9009): 1141-1145. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90608-X.

Kontula K, Ylikorkala A, Miettinen H, Vuorio A, Kauppinen-Makelin R, Hamalainen L, Palomaki H, Kaste M: Arg506Gln factor V mutation (factor V Leiden) in patients with ischaemic cerebrovascular disease and survivors of myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 1995, 73 (4): 558-560.

Lee PN: Smoking and Alzheimer's disease: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Neuroepidemiology. 1994, 13 (4): 131-144. 10.1159/000110372.

Scherr PA, Hebert LE, Smith LA, Evans DA: Relation of blood pressure to cognitive function in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1991, 134 (11): 303-1315.

Xu WL, Qiu CX, Wahlin A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L: Diabetes mellitus and risk of dementia in the Kungsholmen project: a 6-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2004, 63 (7): 1181-1186. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000140291.86406.D1.

McCall AL: The impact of diabetes on the CNS. Diabetes. 1992, 41 (5): 557-570. 10.2337/diabetes.41.5.557.

Biessels GJ, Staekenborg S, Brunner E, Brayne C, Scheltens P: Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5 (1): 64-74. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2.

Aronson MK, Ooi WL, Morgenstern H, Hafner A, Masur D, Crystal H, Frishman WH, Fisher D, Katzman R: Women, myocardial infarction, and dementia in the very old. Neurology. 1990, 40 (7): 1102-1106. 10.1212/WNL.40.7.1102.

Breteler MM, Claus JJ, Grobbee DE, Hofman A: Cardiovascular disease and distribution of cognitive function in elderly people: the Rotterdam Study. Bmj. 1994, 308 (6944): 1604-1608. 10.1136/bmj.308.6944.1604.

Breteler M: Vascular risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: An epidemiologic perspective. Neurobiol Aging. 2000, 21 (2): 153-160. 10.1016/S0197-4580(99)00110-4.

Guo Z, Viitanen M, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B: Low blood pressure and dementia in elderly people: the Kungsholmen project. BMJ. 1996, 312 (7034): 805-808. 10.1136/bmj.312.7034.805.

Lindsay J, Hebert R, Rockwood K: The Canadian Study of Health and Aging: risk factors for vascular dementia. Stroke. 1997, 28 (3): 526-530. 10.1161/01.STR.28.3.526.

Anstey KJ, Mack HA, Cherbuin N: Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 17 (7): 542-555. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181a2fd07.

Sinforiani E, Zucchella C, Pasotti C, Casoni F, Bini P, Costa A: The effects of alcohol on cognition in the elderly: from protection to neurodegeneration. Funct Neurol. 2011, 26: 103-106.

Knopman DS: Cerebrovascular disease and dementia. Br J Radiol. 2007, 80 (Spec 2): 121-127.

Onyike CU: Cerebrovascular disease and dementia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006, 18 (5): 423-431. 10.1080/09540260600935421.

Srikanth V, Saling MM, Thrift AG, Donnan GA: Cerebrovascular disease and dementia. Drug Today (Barc). 2005, 41 (12): 815-825. 10.1358/dot.2005.41.12.933473.

Kovacic JC, Castellano JM, Fuster V: The links between complex coronary disease, cerebrovascular, disease, and degenerative brain disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012, 1254 (1): 99-105. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06482.x.

Deramecourt V, Slade JY, Oakley AE, Perry RH, Ince PG, Maurage CA, Kalaria RN: Staging and natural historyof cerebrovascular pathology indementia. Neurology. 2012, 78 (14): 1043-1050. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8e7f.

Padovani A, Costanzi C, Gilberti N, Borroni B: Parkinson's disease and dementia. Neurol Sci. 2006, 27 (Suppl 1): 40-43.

Porter RJ, Gallagher P, Thompson JM, Young AH: Neurocognitive impairment in drug-free patients with major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003, 182: 214-220. 10.1192/bjp.182.3.214.

Vogels SC, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Verhaar HJ, Koek HD: The association of chronic kidney disease with brain lesions on MRI or CT: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2012, 7 (4): 331-336.

Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, Crowe SF: Cognitive effects of long-term benzodiazepine use: a meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2004, 18 (1): 37-48. 10.2165/00023210-200418010-00004.

Verdoux H, Lagnaoui R, Begaud B: Is benzodiazepine use a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia? A literature review of epidemiological studies. Psychol Med. 2005, 35 (3): 307-315. 10.1017/S0033291704003897.

Anstey KJ, Lipnicki DM, Low LF: Cholesterol as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a systematic review of prospective studies with meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16 (5): 343-354.

Hulse GK, Lautenschlager NT, Tait RJ, Almeida OP: Dementia associated with alcohol and other drug use. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005, 17 (Suppl 1): 109-127.

Goldstein FC, Ashley AV, Endeshaw YW, Hanfelt J, Lah JJ, Levey AI: Effects of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia on cognitive functioning in patients with alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008, 22 (4): 336-342. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318188e80d.

Thoonsen H, Richard E, Bentham P, Gray R, van Geloven N, de Haan RJ, van Gool WA, Nederkoorn PJ: Aspirin in Alzheimer's disease: increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage: cause for concern. Stroke. 2010, 41 (11): 2690-2692. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576975.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/13/129/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Health Research Institute in Taiwan for providing the insurance claims data. This study was supported in part by grants from Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (DOH101-TD-B-111-004) and the Cancer Research Center of Excellence (DOH 101-TD-C-111-005), the National Science Council (NSC 100-2621-M-039-001) and China Medical University Hospital (grant number 1MS1). The funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Cheng KC and Chen YL have equal contribution for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Kao-Chi Cheng: (1) substantial contributions to the conception of this article; (2) planned and conducted the study; (3) initiated the draft of the article and critically revised it; Yu-Lung Chen: (1) substantial contributions to the conception of this article; (2) planned and conducted the study; (3) initiated the draft of the article and critically revised it;Shih-Wei Lai: (1) participated in data interpretation; (2) critically revised the article;Chih-Hsin Mou: (1) conducted data analyses; (2) data interpretation Pang-Yao Tsai: (1) conducted data analyses; (2) data interpretation; Fung-Chang Sung: (1) obtained study materials with substantial contributions to the study concept and design; (2) conducted data analysis and data interpretation; (3) critically revised the article and response to the Reviewers’ comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Kao-Chi Cheng, Yu-Lung Chen contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, KC., Chen, YL., Lai, SW. et al. Patients with chronic kidney disease are at an elevated risk of dementia: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Nephrol 13, 129 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-13-129

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-13-129