Abstract

Background

We report on a patient with genetically confirmed overlapping diagnoses of CMT1A and FSHD. This case adds to the increasing number of unique patients presenting with atypical phenotypes, particularly in FSHD. Even if a mutation in one disease gene has been found, further genetic testing might be warranted in cases with unusual clinical presentation.

Case presentation

The reported 53 years old male patient suffered from walking difficulties and foot deformities first noticed at age 20. Later on, he developed scapuloperoneal and truncal muscle weakness, along with atrophy of the intrinsic hand and foot muscles, pes cavus, claw toes and a distal symmetric hypoesthesia. Motor nerve conduction velocities were reduced to 20 m/s in the upper extremities, and not educible in the lower extremities, sensory nerve conduction velocities were not attainable. Electromyography showed both, myopathic and neurogenic changes. A muscle biopsy taken from the tibialis anterior muscle showed a mild myopathy with some neurogenic findings and hypertrophic type 1 fibers. Whole-body muscle MRI revealed severe changes in the lower leg muscles, tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles were highly replaced by fatty tissue. Additionally, fatty degeneration of shoulder girdle and straight back muscles, and atrophy of dorsal upper leg muscles were seen. Taken together, the presenting features suggested both, a neuropathy and a myopathy. Patient’s family history suggested an autosomal dominant inheritance.

Molecular testing revealed both, a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type 1A (HMSN1A, also called Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy 1A, CMT1A) due to a PMP22 gene duplication and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) due to a partial deletion of the D4Z4 locus (19 kb).

Conclusion

Molecular testing in hereditary neuromuscular disorders has led to the identification of an increasing number of atypical phenotypes. Nevertheless, finding the right diagnosis is crucial for the patient in order to obtain adequate medical care and appropriate genetic counseling, especially in the background of arising curative therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN), also called Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease, is the most common inherited neuromuscular disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1:2,500 [1]. Roughly one third of all cases are caused by an autosomal dominant inherited 1.5 Megabase (Mb) tandem duplication encompassing the peripheral myelin protein 22 gene (PMP22) on chromosome 17p11.2-12 which encodes an important component of peripheral nervous system myelin [2–4]. Phenotypically, patients show a symmetric and distally pronounced muscle weakness and sensory deficits affecting the feet and lower legs and, to a lesser extent, the hands and forearms. Progressive muscle atrophy results in “steppage” gait and secondary foot deformities and can lead to severe disablement. Sensory deficits and paraesthesia are usually less prominent than in other neuropathies. Electrophysiology is an important tool for diagnosis and classification into demyelinating CMT1 (motor conduction velocities (MCVs) of median nerve <38 m/s) and axonal CMT2 (median nerve MCV > 38 m/s). Supportive treatment includes rehabilitative therapy and surgical treatment of skeletal deformities and soft-tissue abnormalities in a multidisciplinary approach [5, 6]. Curative therapeutic options are under investigation.

Autosomal dominant facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is the third most common muscular dystrophy with an estimated prevalence of about 1:20,000 in Europe [7]. The four main diagnostic criteria defining FSHD are (1) onset in facial or shoulder muscles with sparing of extraocular, pharyngeal and lingual muscles and the myocardium, (2) facial weakness in more than half of the affected family members, (3) autosomal dominant inheritance and (4) evidence of a myopathic disease in electromyography and muscle biopsy [8]. The causative gene defect in the large majority (>95%) of FSHD patients is a contraction of a repetitive element on chromosome 4q35 known as D4Z4 to 1 to 10 units (in healthy individuals 11 to 100 units). Because FSHD is apparently not due to a conventional mutation within a neighboring protein-coding gene, the exact pathophysiological mechanism of the repeat loss causing muscle disease is unknown [9]. The phenotypic spectrum is wide, even in the same family, showing a great variability in the level of impairment and disease progression. Therefore, it is still a diagnostic challenge to correctly diagnose FSHD since a broad clinical diversity results from a shortened D4Z4 locus.

With the advent of new causative therapeutic options finding a patient’s correct diagnosis is essential. The case presented here shows a new phenotype of two overlapping neuromuscular diseases which emphasizes the diagnostic challenges.

Case presentation

Methods

The patient was clinically and electrophysiologically examined by the authors.

An open muscle biopsy was performed at the age of 21 after first clinical symptoms occurred. Standard histological examination was carried out as described previously [10] and the muscle biopsy specimens were revisited after disease progression.

Whole-body muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed using a 3.0-T MR system. A routine muscular protocol containing axial T1-weighted (T1w) spin echo sequences was used (slice thickness: 6 mm). The protocol additionally included coronal and axial planes at four levels covering the whole body. The left distal pelvic muscles and proximal femoral muscles could not be examined as the patient had a hip implant.

Using MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification)-analysis (MRC-Holland P033) the PMP22 gene was searched for deletions and duplications. FSHD diagnosis was established by Southern blot analysis for the D4Z4 locus as reported elsewhere [11]. Furthermore, the mutation-hot spot region of the myotilin gene was examined by direct sequencing of exon 2 (NM_006790).

This case report was exempt as part of the patient’s standard care. The patient consented to all performed diagnostic analyses as part of a standard diagnostic work-up and care as well as the publication of his clinical data, images (clinical photographs, MRI, muscle biopsy) and videos. However, he preferred to have his face made unrecognizable on the photos. Additionally, his family members gave permission for publication of their medical histories.

Clinical data

Childhood and adolescence were reported normal. First clinical symptoms were noted at age 20 with pes cavus, claw toes and walking difficulties. During the 5th decade, weakness of arm elevation and distal weakness of hands affecting the dorsal interossei with reduced abduction in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints and a weakness in thumb abduction occurred. The patient reported mild hypoesthesia of fingers and toes and he had marked difficulties to button up his shirt. He walked unaided and maximum walking distance was not impaired.

Clinical examination revealed a scapuloperoneal phenotype associated with pectoralis muscle atrophy, truncal weakness and scapular winging. The patient was not able to lift his arms above the horizontal level. There was no facial and bulbar weakness and no Beevor’s sign. He did not suffer from scoliosis or contractures. Standing or walking on toes or heels was not possible and in heel to toe walking (tandem gait) an unsteady gait, probably due to sensory loss, was observed. Additionally, lower limb weakness (extensor digitorum MRC 4/5, abductor pollicis MRC 4/5, tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles MRC 2/5) along with marked muscle atrophy was found. Distal symmetric hypoesthesia and the described foot deformities were observed (Figure 1). Deep tendon reflexes were absent. Needle EMG showed mild myopathic changes in proximal muscles such as M. biceps brachii and M. iliopsoas and neurogenic changes in tibialis anterior muscles. Nerve conduction velocities in upper limb motor nerves showed a demyelinating neuropathy (median nerve 17 m/s, DML 9.5 ms; ulnar nerve 21 m/s, DML 7.2 ms). Compound motor action potentials (CMAPs) were normal in amplitude without signs of conduction block or temporal dispersion. Lower limb motor nerves were not educible. Sensory nerve conduction velocities were repeatedly not attainable. CK levels were elevated up to 300 U/l (normal value < 180).

In summary, the patient presented with a scapuloperoneal weakness and atrophy, foot deformities along with sensorimotor demyelinating neuropathy and mild hyerCKemia.

Family history

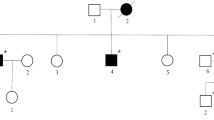

The patient has three siblings (two sisters age 49 and 61, and one brother age 51). One sister and her daughter suffer from a sensorimotor neuropathy, but were not available for further investigations. The parents were reported healthy, however, the father died early at age 49 due to an accident and the mother died at age 68 due to gastric cancer. The mother’s four siblings and their progenies as well as the patient’s grandparents were reported healthy (Figure 2).

Family history. The patient’s parents died early and had no symptoms of muscle weakness or neuropathy. Neither did the mother’s four siblings and their progenies. Besides our patient one of his sisters and her older daughter show similar symptoms of peripheral neuropathy with foot deformities and gait difficulties. No symptoms of muscle wasting or weakness occurred in these two family members until now.

MRI

The muscle MRI showed the most severe changes in the lower leg muscles. Tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles were largely replaced by fatty tissue. Besides, fatty degeneration of serratus, latissimus dorsi and straight back muscles (data not shown) as well as atrophy of dorsal upper leg muscles, mainly biceps femoris and semimembranosus, were seen (Figure 3).

MR imaging. Whole-body MRI shows nearly complete fatty atrophy of the tibialis anterior muscles and the Mm. gastrocnemii, as well as moderate fatty replacement of muscle tissue in the soleus muscle (A, C). Atrophy of the dorsal upper leg muscles is pronounced in the M. semimembranosus and M. biceps femoris (B). Gluteal muscles revealed mild fatty degeneration. Additionally, fatty muscle degeneration of scapular fixators (Mm. serrati and Mm. latissimi dorsi) and axial back muscles was detected (data not shown). The pelvis and proximal upper legs were not examined as the patient had a hip implant.

Muscle biopsy

An open muscle biopsy of the left tibialis anterior muscle was performed at the age of 21. It showed mild myopathic alterations with fiber splitting and increase of endomysial connective tissue, however some small neurogenic-like muscles fibers and numerous hypertrophic type I fibers were seen. This biopsy did not reveal any necrotic fibers or inflammatory changes (Figure 4A). ATPase staining revealed no fiber type grouping, but a type-1 fiber predominance of up to 80%, as commonly seen in anterior tibial muscle (Figure 4B). Trichrome staining showed no ragged red fibers. No myofibrillar or mitochondrial changes were detected.

Muscle biopsy. (A) H&E staining of a muscle biopsy of the left anterior tibial muscle with mild myopathic changes indicated by muscle fiber splitting and increase in endomysial connective tissue. Additionally, in the ATPase pH 4.1 staining (B), a type I fiber predominance without evidence of fiber type grouping and numerous hypertrophic type I fibers are notable. Bars in A and B adjusted to 50 μm.

Molecular analysis

Molecular analysis of the PMP22 gene showed the typical duplication encompassing the PMP22 gene on chromosome 17p11.2-12 confirming the diagnosis of CMT1A. No mutations were found in exon 2 of the myotilin gene. A shortened chromosome 4q-specific fragment of 19 kb in the D4Z4 locus (FSHD repeat) and the FSHD-related 4qA haplotype were observed leading to the diagnosis of FSHD.

Discussion

Both hereditary sensorimotor neuropathy due to PMP22 duplication (CMT1A) and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) due to a shortened fragment of the D4Z4 locus (19 kb) were identified in the described patient. To the best of our knowledge this is one of only three published cases describing coincidence of CMT1A and FSHD.

Recent epidemiological data suggest that the frequency of CMT1A is around 1:7,500 [4] while the frequency of FSHD is estimated at 1:20,000 [7]. Thus, the chance of being affected by both disorders is about 1:150,000,000.

In the patient’s family history his sister and her daughter were suggestive of CMT1A as well. However, since both parents have died and no DNA samples of further family members were available, segregation could not be proven. Our patient showed typical symptoms of this generalized, primarily demyelinating neuropathy with reduced nerve conduction velocities, distal hypoesthesia and distal muscle atrophy leading to steppage gait and foot deformities like pes cavus und claw toes [1].

Since additional features like proximal muscle weakness of the shoulder girdle, myopathic changes in muscle biopsy specimen and EMG analysis were suggestive of additional primary involvement of the skeletal muscle genetic analyses were extended to include frequent forms of muscular dystrophies and myopathies. FSHD diagnosis was established by Southern blot analysis for the D4Z4 locus showing contraction of the repeat (19 kb) and a FSHD-related 4qA haplotype. It remains unclear if FSHD results from a de novo mutation occurring in 10% to 30% of all cases [12] or from familial inheritance as we cannot rule out the possibility of an undiagnosed mild presentation in other family members. Until now, the pathogenic relevance of the D4Z4 deletion has not been fully clarified and has been questioned in recent studies [13]. However, in addition to the clinical findings, electromyography in our patient revealed mild myopathic changes in proximal muscles along with the myopathic changes in the muscle biopsy specimen. Along with shortening of the D4Z4 locus to 19 kb on EcoRI + BlnI double digestion, FSHD is likely to be causative for the additional myopathy.

The classical FSHD phenotype was described in 1884 by Landouzy and Dejerine with facial weakness, shoulder girdle and pectoral muscle weakness and atrophy, in some cases resulting in subsequent impairment of pelvic and lower leg muscles [14]. But clinical variability has long been recognized in neuromuscular disorders. This has become most obvious with the advent of molecular genetic testing showing that identical molecular defects can result in diverse clinical presentations. This is especially true for FSHD where several unusual phenotypes and atypical morphological features ranging from hyperCKemia, severe muscle pain, facial-sparing, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, camptocormia, distal and axial myopathy, along with atypical morphological changes such as vacuolar and/or inflammatory myopathy, nemaline rods, and deficiency of complex III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain were reported [15–23]. Our patient provides further evidence for this variability by not fulfilling all four major diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of FSHD as described above [8]. Autosomal dominant inheritance cannot be proven since the parents were not available for molecular testing, and facial weakness was not seen.

Interfamilial and intrafamilial clinical variability has also been observed in CMT [24, 25] including cases of demyelinating CMT with scapuloperoneal distribution of motor impairment reported in the 1980s [26, 27]. In contrast to our case, these cases were confined to clinical findings since molecular genetic testing was not yet available in the 1980s. Harding and Thomas described a constellation of clinical symptoms similar to our patient but with striking wasting of both deltoid muscles which is rather uncommon in FSHD so that we cannot exclude that this patient suffered from another scapuloperoneal myopathy.

In addition to stochastic effects, environmental influences, allelic variation, modifier genes, somatic mosaicism and complex genetic and environmental interactions [28], some of this variability might be caused by concomitant mutations in other genes for neuromuscular conditions. In FSHD, such overlapping syndromes have been described several times in literature. Association with pathogenic mutations in other genes have been reported in cases of patients with mitochondrial myopathy/FSHD, Becker muscular dystrophy/FSHD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy/FSHD, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy/FSHD and caveolinopathy/FSHD determining overlapping phenotypes [15, 29–33]. For CMT1A, concomitant mutations in the PMP22 gene and the Connexin32 gene (causing CMTX), the DMPK1 gene (DM1 myotonic dystrophy) and the ABCD1 gene (adrenomyeloneuropathy) have been described to produce peculiar phenotypes [34]. In addition, a combination of CMTX with Becker muscular dystrophy has been reported [35], causing both, generalized weakness and CK elevation as typical phenotype for a muscular dystrophy as well as foot deformity, decreased tendon reflexes and sensory loss due to a mutation in the Connexin32 gene.

There is one further report similar to ours on one family suffering from CMT1A and FSHD [36]. Auer-Grumbach et al. reported on this family affected by genetically confirmed CMT1A with scapuloperoneal motor deficit but conflicting data concerning the concomitant presence of FSHD. Co-segregation of FSHD in this family was unconvincing and haplotype analysis on chromosome 4q was not performed as it was not described in the paper. In contrast to our report, no muscle histology was performed and EMG revealed a mild chronic neurogenic pattern in proximal and distal muscles. However, our patient showed myopathic changes assessed by electromyography and muscle biopsy which further support the molecular diagnosis of FSHD.

In our patient a contracted fragment of 19 kb in the D4Z4 locus was detected. It is generally accepted that there is a correlation between clinical severity and size of the D4Z4 repeat: small repeats stand for early age at onset and severe clinical course, whereas larger repeats mean later age at onset and milder course [37]. Although the patient reported here carries a repeat size usually expected to result in a moderately severe phenotype with onset in the 1st or 2nd decade, he showed only mild symptoms of shoulder girdle weakness developing in the second half of life without facial or proximal leg muscle impairment until now. There is no obvious explanation for the unexpectedly mild phenotype in our patient and in contrast, the association of FSHD with X-linked CMT and Duchenne muscular dystrophy leads to severe infantile phenotypes [31, 38]. Butefisch et al. described a further patient with the combination of CMT1A and FSHD in 1998 [39]. This female patient inherited CMT1A from her father and FSHD from her mother and this comorbidity resulted in severe generalized weakness, respiratory insufficiency and early death. However, according to the information given in the paper, only the diagnosis of CMT1A was proven by molecular testing but not the FSHD, neither in the patient nor in relatives. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that another progressive muscular dystrophy might be causative for this devastating clinical course in this patient.

All in all, too few “double trouble” patients are known to draw significant conclusions on how concomitant genetic conditions modify each other’s severity and progression in these patients. Nevertheless, the number of cases with genetically proven double trouble is likely to increase with the availability of improved genetic testing and whole exome or genome sequencing methods. This will result in an even broader variety of atypical clinical pictures but may also help to understand interference at the phenotypic, genetic and epigenetic levels having a direct impact on medical care and genetic counseling.

Conclusion

Our case reports on a patient with genetically confirmed overlapping diagnoses of CMT1A and FSHD. It adds to the increasing number of unique patients presenting with atypical and overlapping phenotypes, particularly in FSHD. Even if a mutation in a disease gene has been found, further genetic testing might be warranted in cases with unusual clinical presentation having a direct impact on medical care and genetic counseling.

Consent

This study was exempt as part of the patient’s standard care. The patient consented to all performed diagnostic analyses as part of a standard diagnostic work-up and care as well as the publication of his clinical data, images (clinical photographs, MRI, muscle biopsy) and videos. However, he preferred to have his face made unrecognizable on the photos. Additionally, his family members gave permission for publication of their medical histories. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

References

Reilly MM, Murphy SM, Laura M: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011, 16: 1-14.

Lupski JR, de Oca-Luna RM, Slaugenhaupt S, Pentao L, Guzzetta V, Trask BJ, Saucedo-Cardenas O, Barker DF, Killian JM, Garcia CA, et al: DNA duplication associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Cell. 1991, 66: 219-232. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90613-4.

Raeymaekers P, Timmerman V, Nelis E, De Jonghe P, Hoogendijk JE, Baas F, Barker DF, Martin JJ, De Visser M, Bolhuis PA, et al: Duplication in chromosome 17p11.2 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 1a (CMT 1a). The HMSN Collaborative Research Group. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991, 1: 93-97. 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90055-W.

Gess B, Schirmacher A, Boentert M, Young P: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: frequency of genetic subtypes in a German neuromuscular center population. Neuromuscul Disord. 2013, 23: 647-651. 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.05.005.

Pareyson D, Marchesi C: Diagnosis, natural history, and management of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8: 654-667. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70110-3.

Young P, De Jonghe P, Stogbauer F, Butterfass-Bahloul T: Treatment for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, 1: CD006052-

Orrell RW: Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy and scapuloperoneal syndromes. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011, 101: 167-180.

Padberg GW, Lunt PW, Koch M, Fardeau M: Diagnostic criteria for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991, 1: 231-234. 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90094-9.

Neguembor MV, Gabellini D: In junk we trust: repetitive DNA, epigenetics and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Epigenomics. 2010, 2: 271-287. 10.2217/epi.10.8.

Weis J, Schroder JM: Adult polyglucosan body myopathy with subclinical peripheral neuropathy: case report and review of diseases associated with polyglucosan body accumulation. Clin Neuropathol. 1988, 7: 271-279.

de Greef JC, Lemmers RJ, van Engelen BG, Sacconi S, Venance SL, Frants RR, Tawil R, van der Maarel SM: Common epigenetic changes of D4Z4 in contraction-dependent and contraction-independent FSHD. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: 1449-1459. 10.1002/humu.21091.

Lemmers RJ, van der Wielen MJ, Bakker E, Padberg GW, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM: Somatic mosaicism in FSHD often goes undetected. Ann Neurol. 2004, 55: 845-850. 10.1002/ana.20106.

Scionti I, Greco F, Ricci G, Govi M, Arashiro P, Vercelli L, Berardinelli A, Angelini C, Antonini G, Cao M, et al: Large-scale population analysis challenges the current criteria for the molecular diagnosis of fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2012, 90: 628-635. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.019.

Landouzy L, Déjerine J: De la myopathie atrophique progressive (myopathie héréditaire débutant dans l’enfance, par la face sans altération du système nerveux). C R Seances Acad Sci. 1884, 98: 53-58.

Slipetz DM, Aprille JR, Goodyer PR, Rozen R: Deficiency of complex III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in a patient with facioscapulohumeral disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1991, 48: 502-510.

Bushby KM, Pollitt C, Johnson MA, Rogers MT, Chinnery PF: Muscle pain as a prominent feature of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD): four illustrative case reports. Neuromuscul Disord. 1998, 8: 574-579. 10.1016/S0960-8966(98)00088-1.

Felice KJ, North WA, Moore SA, Mathews KD: FSH dystrophy 4q35 deletion in patients presenting with facial-sparing scapular myopathy. Neurology. 2000, 54: 1927-1931. 10.1212/WNL.54.10.1927.

Wood-Allum C, Brennan P, Hewitt M, Lowe J, Tyfield L, Wills A: Clinical and histopathological heterogeneity in patients with 4q35 facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004, 30: 188-191. 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2003.00520.x.

Zouvelou V, Manta P, Kalfakis N, Evdokimidis I, Vassilopoulos D: Asymptomatic elevation of serum creatine kinase leading to the diagnosis of 4q35 facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. J Clin Neurosci. 2009, 16: 1218-1219. 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.004.

Tsuji M, Kinoshita M, Imai Y, Kawamoto M, Kohara N: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy presenting with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009, 19: 140-142. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.11.011.

Reilich P, Schramm N, Schoser B, Schneiderat P, Strigl-Pill N, Muller-Hocker J, Kress W, Ferbert A, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Noth J, et al: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy presenting with unusual phenotypes and atypical morphological features of vacuolar myopathy. J Neurol. 2010, 257: 1108-1118. 10.1007/s00415-010-5471-1.

Kottlors M, Kress W, Meng G, Glocker FX: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy presenting with isolated axial myopathy and bent spine syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2010, 42: 273-275. 10.1002/mus.21722.

Jordan B, Eger K, Koesling S, Zierz S: Camptocormia phenotype of FSHD: a clinical and MRI study on six patients. J Neurol. 2011, 258: 866-873. 10.1007/s00415-010-5858-z.

Pareyson D, Scaioli V, Laura M: Clinical and electrophysiological aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2006, 8: 3-22. 10.1385/NMM:8:1-2:3.

Birouk N, Gouider R, Le Guern E, Gugenheim M, Tardieu S, Maisonobe T, Le Forestier N, Agid Y, Brice A, Bouche P: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A with 17p11.2 duplication. Clinical and electrophysiological phenotype study and factors influencing disease severity in 119 cases. Brain. 1997, 120: 813-823. 10.1093/brain/120.5.813.

Ronen GM, Lowry N, Wedge JH, Sarnat HB, Hill A: Hereditary motor sensory neuropathy type I presenting as scapuloperoneal atrophy (Davidenkow syndrome) electrophysiological and pathological studies. Can J Neurol Sci. 1986, 13: 264-266.

Harding AE, Thomas PK: Distal and scapuloperoneal distributions of muscle involvement occurring within a family with type I hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. J Neurol. 1980, 224: 17-23. 10.1007/BF00313203.

Zlotogora J: Penetrance and expressivity in the molecular age. Genet Med. 2003, 5: 347-352. 10.1097/01.GIM.0000086478.87623.69.

Filosto M, Tonin P, Scarpelli M, Savio C, Greco F, Mancuso M, Vattemi G, Govoni V, Rizzuto N, Tupler R, Tomelleri G: Novel mitochondrial tRNA Leu(CUN) transition and D4Z4 partial deletion in a patient with a facioscapulohumeral phenotype. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008, 18: 204-209. 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.12.005.

Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Weis J, Kress W, Hausler M, Zerres K: Becker’s muscular dystrophy aggravating facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy–double trouble as an explanation for an atypical phenotype. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008, 18: 881-885. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.06.387.

Korngut L, Siu VM, Venance SL, Levin S, Ray P, Lemmers RJ, Keith J, Campbell C: Phenotype of combined Duchenne and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008, 18: 579-582. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.03.011.

Chuenkongkaew WL, Lertrit P, Limwongse C, Nilanont Y, Boonyapisit K, Sangruchi T, Chirapapaisan N, Suphavilai R: An unusual family with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Eur J Neurol. 2005, 12: 388-391. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.01060.x.

Ricci G, Scionti I, Ali G, Volpi L, Zampa V, Fanin M, Angelini C, Politano L, Tupler R, Siciliano G: Rippling muscle disease and facioscapulohumeral dystrophy-like phenotype in a patient carrying a heterozygous CAV3 T78M mutation and a D4Z4 partial deletion: Further evidence for “double trouble” overlapping syndromes. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012, 22: 534-540. 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.12.001.

Hodapp JA, Carter GT, Lipe HP, Michelson SJ, Kraft GH, Bird TD: Double trouble in hereditary neuropathy: concomitant mutations in the PMP-22 gene and another gene produce novel phenotypes. Arch Neurol. 2006, 63: 112-117. 10.1001/archneur.63.1.112.

Bergmann C, Senderek J, Hermanns B, Jauch A, Janssen B, Schroder JM, Karch D: Becker muscular dystrophy combined with X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2000, 23: 818-823. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(200005)23:5<818::AID-MUS23>3.0.CO;2-O.

Auer-Grumbach M, Wagner K, Strasser-Fuchs S, Loscher WN, Fazekas F, Millner M, Hartung HP: Clinical predominance of proximal upper limb weakness in CMT1A syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2000, 23: 1243-1249. 10.1002/1097-4598(200008)23:8<1243::AID-MUS13>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Lunt PW, Jardine PE, Koch MC, Maynard J, Osborn M, Williams M, Harper PS, Upadhyaya M: Correlation between fragment size at D4F104S1 and age at onset or at wheelchair use, with a possible generational effect, accounts for much phenotypic variation in 4q35-facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). Hum Mol Genet. 1995, 4: 951-958. 10.1093/hmg/4.5.951.

Lecky BR, MacKenzie JM, Read AP, Wilcox DE: X-linked and FSH dystrophies in one family. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991, 1: 275-278. 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90101-W.

Butefisch CM, Lang DF, Gutmann L: The devastating combination of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1998, 21: 788-791. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199806)21:6<788::AID-MUS11>3.0.CO;2-P.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/14/92/prepub

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the patient and his family for participation in this study. We thank Dr. med. Eva Coppenrath and Dr. med. Christoph Degenhart, Dept. of Radiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, for reviewing the whole-body muscle MRI. OS, PS, WK, BR, BS and MCW are members of the German network on muscular dystrophies (MD-NET, 01GM0887) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Bonn, Germany). MD-NET is a partner of TREAT-NMD (EC, 6th FP, proposal no. 036825). The article processing charge was funded by the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich in the funding program Open Access Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

OS, PS and MCW performed the clinical diagnostics of the patient. WK carried out the molecular genetic studies of the myotilin gene and the D4Z4 locus for FSHD. BR carried out the molecular genetic studies of the PMP22 gene. JS has revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. BS carried out the further processing of the muscle biopsy and interpreted the results. OS and PS contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Olivia Schreiber, Peter Schneiderat contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schreiber, O., Schneiderat, P., Kress, W. et al. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy and Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy 1A - evidence for “double trouble” overlapping syndromes. BMC Med Genet 14, 92 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-14-92

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-14-92