Abstract

Background

Polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) are myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) characterized in most cases by a unique somatic mutation, JAK2 V617F. Recent studies revealed that JAK2 V617F occurs more frequently in a specific JAK2 haplotype, named JAK2 46/1 or GGCC haplotype, which is tagged by rs10974944 (C/G) and/or rs12343867 (T/C). This study examined the impact of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the JAK2 locus on MPNs in a Japanese population.

Methods

We sequenced 24 JAK2 SNPs in Japanese patients with PV. We then genotyped 138 MPN patients (33 PV, 96 ET, and 9 PMF) with known JAK2 mutational status and 107 controls for a novel SNP, in addition to two SNPs known to be part of the 46/1 haplotype (rs10974944 and rs12343867). Associations with risk of MPN were estimated by odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals using logistic regression.

Results

A novel locus, rs4495487 (T/C), with a mutated T allele was significantly associated with PV. Similar to rs10974944 and rs12343867, rs4495487 in the JAK2 locus is significantly associated with JAK2-positive MPN. Based on the results of SNP analysis of the three JAK2 locus, we defined the "GCC genotype" as having at least one minor allele in each SNP (G allele in rs10974944, C allele in rs4495487, and C allele in rs12343867). The GCC genotype was associated with increased risk of both JAK2 V617F-positive and JAK2 V617F-negative MPN. In ET patients, leukocyte count and hemoglobin were significantly associated with JAK2 V617F, rather than the GCC genotype. In contrast, none of the JAK2 V617F-negative ET patients without the GCC genotype had thrombosis, and splenomegaly was frequently seen in this subset of ET patients. PV patients without the GCC genotype were significantly associated with high platelet count.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the C allele of JAK2 rs4495487, in addition to the 46/1 haplotype, contributes significantly to the occurrence of JAK2 V617F-positive and JAK2 V617F-negative MPNs in the Japanese population. Because lack of the GCC genotype represents a distinct clinical-hematological subset of MPN, analyzing JAK2 SNPs and quantifying JAK2 V617F mutations will provide further insights into the molecular pathogenesis of MPN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) represent a heterogeneous group of hematological malignancies characterized by clonal hematopoiesis and an increased number of mostly peripheral blood elements of myeloid origin [1]. The classic Philadelphia-chromosome negative MPNs encompass three distinct diseases, namely polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) [2–5]. Identification of the V617F mutation of the JAK2 gene (JAK2 V617F) led to an important breakthrough in the understanding of MPN disease pathogenesis [2–5]. The JAK2 V617F mutation is present in the majority of PV patients, and about 50% of patients with ET and PMF are affected [2–5]. Because this somatic mutation is highly specific to MPNs, it has been designated as a major diagnosis criterion for PV, ET, and PMF according to the latest World Health Organization classification of MPNs [6].

Recent investigations revealed that somatic acquisition of genetic aberrations is one pathogenic mechanism, but inherited genetic factors also play an important role in the development of MPN. Several independent groups reported that a particular JAK2 haplotype, designated 46/1 or GGCC, is strongly associated with the development [7–9], or with MPN development, regardless of the JAK2 mutational status [10, 11]. Olcaydu et al. [12] performed JAK2 haplotype analysis in familial MPNs, and they concluded that even if JAK2 46/1 is related to the development of MPN independent of V617F status, it has to be regarded as only one of the genetic factors involved in the development of MPN. Moreover, Jones et al. [13] found correlations in JAK2 wild-type MPN between JAK2 46/1 and both MPL exon 10 and JAK2 exon 12.

In the present study, we attempted to find novel single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the JAK2 locus in a Japanese population. We then examined whether JAK2 SNPs are indeed associated with a predisposition to MPNs, especially in JAK2 V617F-positive MPNs.

Methods

Patients

In the current study conducted at the Tokyo Medical University Hospital, 138 constitutive Japanese MPN patients aged 30-87 years with known JAK2 V617F status were included: 33 patients with JAK2 V617F-positive PV, 57 patients with JAK2 V617F-positive ET, 39 patients with JAK2 V617F-negative ET, and 9 patients with PMF. The patients experienced no familial MPNs. We revised their classification at diagnosis according to the latest World Health Organization classification of MPNs. As controls, 107 healthy volunteers aged 24-86 years from the same demographic area in Japan were used. The JAK2 V617F mutation detection system used was reported elsewhere [14], and the JAK2 V617F mutational status was categorized according to the allele burden of mutated T allele. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Tokyo Medical University (no. 975). Written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from all patients prior to collection of the specimens.

PCR direct sequencing of the JAK2 locus

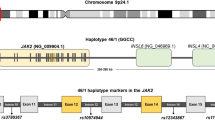

Genomic DNA was obtained from whole blood using an automated system (Qiagen). To identify novel SNPs in the JAK2 locus in this Japanese population, primer sets for the amplification of JAK2 were designed according to GenBank AL161450 (Figure 1A; Additional file 1A). PCR conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min for 36 cycles using High FidelityPLUS PCR System dNTPack (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The PCR products were purified by a High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemical Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and sequenced using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer. The obtained sequences were compared with the JAK2 sequence.

Schematic representation of the JAK2 locus. (A) Loci of SNPs are shown as black dots. Two SNPs included in the 46/1 haplotype are shown at the right end (rs12343867) and left end (rs10974944). A new candidate SNP is shown in the middle of those, near exon 13. Primers used for sequencing, a forward primer (int-12F) and four reverse primers (int-12-R, exon13-R, int-13R, and int-14R), are shown. (B) Location of primers used for allele-specific PCR. The larger fragment (3158 bp) was amplified using a forward primer (int-12F) and two sets of reverse primers (exon14-R or V617F-R) that can discriminate two alleles with or without JAK2 V617F. The smaller fragment was amplified using two forward primers (exon 14-F or V617F-F) and one reverse primer (int-14R). Detailed information on primers is given in Additional File 1.

Allele-specific PCR analysis

To determine whether minor alleles of JAK2 SNPs favor the cis acquisition of JAK2 V617F, we performed allele-specific analysis of six SNPs in patients with PV. The sequence JAK2 nt51936-nt55084 (3158 bp) was amplified using forward primer int12-F and reverse primer V617F-R or exon14-R. The primer set for the amplification of JAK2 nt55038-nt55636 (598 bp) was forward primer V617F-F or exon14-F and reverse primer int14-R. Both primers V617F-R and V617F-F could amplify the T allele of JAK2 V617F (Figure 1B; Additional file 1A). The PCR products were purified and sequenced as described above.

Genotyping

Allele-specific PCR was performed with a common forward primer and two allele-specific reverse primers (Additional file 1B) using High FidelityPLUS PCR System dNTPack (Roche Diagnostics) and SYBR Green I (Lonza, Rockland, ME, USA). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min for 40 cycles using an iCycler iQ Real-time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). To avoid nonspecific PCR products, melting analysis was performed by denaturing at 95°C for 1 min and cooling to 55°C for 1 min followed by heating at the rate of 0.5°C/10 s from 55 to 95°C.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Associations with risk of MPNs were estimated by odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) using logistic regression. A Mann-Whitney U-test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between the control and test groups. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences. We also performed multivariate analysis using College analysis software (version 4.5, Fukuyama Heisei University, Fukuyama, Japan) to exclude possible false correlation between genotype and clinical manifestations.

Results

Minor allele frequency of SNPs from the JAK2 locus in Japanese PV patients

We first screened for 24 SNPs of the JAK2 locus around exons 12 to 14 in 28 Japanese patients with JAK2 V617F-positive PV from whom we obtained sufficient DNA for this analysis (Figure 1A). Among them, minor allele frequencies in six SNPs (rs10974944, rs12686652, rs12335546, rs4495487, rs1028730, and rs12343867) were significantly higher in PV patients than in healthy volunteers (Table 1). There were no significant differences in age or sex between the PV population and healthy controls (data not shown). Minor allele frequency was estimated by total cases that had at least one minor allele (heterozygous) or two minor alleles (homozygous). The JAK2 SNP rs4495487, which has not been reported previously in Caucasian populations, showed the highest OR (13.8, 95% CI: 3.79-50.21) among the six SNPs.

To determine whether minor alleles of JAK2 SNPs favor the cis acquisition of JAK2 V617F, we next sequenced six SNPs using allele-specific primers (Additional file 1A). In accordance with a previous report [8], in the genotype with minor alleles in all six SNPs, the T allele was more frequently observed in JAK2 V617F than the G allele in normal controls; the OR was 7.74 (95% CI: 2.32-25.75) (Additional file 2).

JAK2 SNP distribution in MPN patients and controls

We genotyped 138 MPN patients with known JAK2 mutational status and 107 controls for JAK2 SNP rs449587 in addition to two SNPs that are known to be part of the 46/1 haplotype (rs10974944 and rs12343867). Overall, 95 MPN patients (68.8%) were JAK2 V617F positive. When analyzing each MPN entity separately, we found that 33 PV patients (100%), 57 ET patients (63.3%), and 5 PMF patients (55.5%) were JAK2 V617F positive. The distribution of JAK2 SNPs (rs10974944, rs4495487, and rs12343867) is listed in Table 2. Allelic variation of three JAK2 SNPs was strongly associated with JAK2-positive MPN (all patients with PV, 57 patients with ET, and 5 patients with PMF) and much less strongly associated with JAK2-negative MPN (39 patients with ET and 4 patients with PMF). It is notable that allelic variation of the JAK2 SNP rs4495487 showed the highest OR in each population. The JAK2 SNP variation in 9 PMF patients is listed in Additional file 3. Because allelic variation of rs4495487 showed the highest OR in each patient population, we arbitrarily named genetic variation as the "GCC genotype," which has at least one minor allele in each of the three SNPs (G allele in rs10974944, C allele in rs4495487, and C allele in rs12343867); patients having the 46/1 haplotype and C allele of rs4495487. The GCC genotype is strongly associated with JAK2 V617F-positive MPNs (OR: 3.07; 95% CI: 1.73-5.46) and modestly associated with JAK2 V617F-negative MPN (OR: 2.26, 95% CI: 1.01-4.7) compared to normal controls (Table 3). The occurrence of the GCC genotype, however, did not depend on JAK2 V671F allele burden (Table 4).

Clinical and hematological features, JAK2 V617F, and the GCC genotype

We compared the clinical and hematological features of PV and ET patients with or without the GCC genotype. We subdivided ET patients into four groups: JAK2 V617F-negative ET patients with or without the GCC genotype and JAK2 V617F-positive ET patients with or without the GCC genotype (Table 5). None of the JAK2 V617F-negative ET patients without the GCC genotype had thrombosis (p = 0.0446), and splenomegaly was more frequently seen in this subset of ET patients (p = 0.0448), indicating that JAK2 V617F-negative ET without genetic variation shows a distinct clinical feature. White blood cell counts were significantly elevated in patients with JAK2 V617F-positive ET, regardless of GCC genotype status (p = 0.0399) (Figure 2A). Hemoglobin levels were significantly elevated in patients with both JAK2 V617F and the GCC genotype compared to those with the GCC genotype but lacking JAK2 V617F (p = 0.002) (Figure 2B). There was no significant difference in platelet counts among the four groups. These results indicate that the proliferative nature of MPNs, such as increased white blood cell and hemoglobin counts, may be linked to JAK2 V617F, regardless of JAK2 genetic variations.

Comparison of hematological features in ET and PV patients divided by JAK2 V617F mutational status and/or germline genetic variation (GCC genotype). (A) White blood cell (WBC) counts were significantly elevated in patients with JAK2 V617F-positive ET, regardless of GCC genotype (p = 0.0399). (B) Hemoglobin (Hb) levels were significantly elevated in ET patients having both JAK2 V617F and GCC genotype compared to those showing the GCC genotype but lacking JAK2 V617F (p = 0.002). (C) There was no significant difference in platelet count among ET groups. (D) Leukocyte count in PV patients. (E) Hemoglobin levels in PV patients. (F) Platelet count was significantly elevated in PV patients without the GCC genotype (p = 0.015).

Because all the PV patients in the current study were JAK2 V617F positive, we compared the clinical and hematological features between PV patients with or without the GCC genotype (Table 6). Although there were no significant differences in age, sex, clinical manifestations, or survival between the two groups, platelet count was significantly elevated in PV patients without the GCC genotype (p = 0.015) (Figure 2). These findings suggest that germline genetic variation also affects PV patients.

Discussion

This is the first study to provide evidence of an association between somatic JAK2 V617F mutation and JAK2 SNPs in a Japanese population of MPN patients. We found a candidate SNP, rs4495487, that may contribute to MPN phenotype in this population. A contribution of this SNP has not been reported in Caucasian populations; however, because it is located between rs1097944 and rs12343867, rs4495487 might be included in the 46/1 haplotype. As in previous reports, we found a significant association between JAK2 SNPs and MPN phenotype in JAK2 V617F-positive MPNs [7–9] and in JAK2 V617F-negative MPNs [10, 11].

Although the occurrence of JAK2 V617F greatly contributes to the diagnosis of MPNs, it remains unclear why this single genetic change represents at least three clinical phenotypes (i.e., PV, ET, and PMF). It also remains uncertain whether JAK2 V617F is the primary genetic change responsible for MPNs. Thus, the major obstacle to clarifying the molecular pathogenesis of MPNs is the substantial complexity of the genetic changes, including germline genetic variation of the JAK2 locus.

In the present study, we demonstrated an association between germline genetic variation in the JAK2 locus and MPN phenotype in a Japanese population. Although the clinical manifestation largely depends on JAK2 V617F mutation rather than SNPs in the JAK2 locus of ET patients, we noted that JAK2 V617F-negative ET without the GCC genotype showed a distinct clinical feature, suggesting an underlying genetic change that has not yet been identified. Tefferi et al. [11] demonstrated that nullizygosity for the JAK2 46/1 haplotype is associated with inferior survival. Taken together, these findings suggest that the lack of certain germline genetic variation may play an important role in the pathogenesis of MPNs. In a study by Trifa et al. [15], the 46/1 haplotype was associated with mutant allele burden > 50% in JAK2 V617F-positive MPN patients. However, we could not find any relationship between allele burden and germline genetic variations. Although we found an association between splenomegaly and JAK2 V617F-negative ET without the GCC genotype, a previous report by Vannucchi et al. [16] demonstrated JAK2 V617F mutation was related to larger spleen size in ET. In addition, we found no significant differences in platelet count among the ET groups, unlike previous reports [16, 17]. These discrepancies could be related to differences in the size or ethnics of the analyzed patient cohorts. Therefore, larger studies of Japanese patients should be conducted to clarify the association between JAK2 V617 allele burden and JAK2 haplotype.

According to a recent report by Colaizzo et al. [18], in patients with splanchnic venous thrombosis, the JAK2 V617F mutation is frequently found in women and, when interacting with the 46/1 haplotype, it may represent a gender-related susceptibility allele for splanchnic venous thrombosis. In the current study, we found no relationships between sex or genotype and the occurrence of thrombosis. However, future research should clarify whether sex modulation of those genetic changes also occur in Asian populations. In the present study, none of the JAK2 V617F-negative ET patients without the GCC genotype had the complication of thrombosis. Smalberg et al. [19] recently demonstrated that the 46/1 haplotype is associated with the development of JAK2 V617F-positive splenic vein thrombosis (SVT), but the existence of JAK2 V617F-negative SVT patients also indicates an important role for the 46/1 haplotype in the etiology and diagnosis of SVT-related MPNs. In contrast, Kouroupi et al. [20] showed that the 46/1 haplotype is not a susceptibility locus for the development of SVT. Thus, further exploration is required to clarify whether the JAK2 germline variation is a risk factor of thrombosis. It is notable that platelet count was significantly higher in PV patients without the GCC genotype. Although this is partially due to the relative iron deficiency during the expansion of the PV clone, these findings suggest that a lack of germline genetic variation (i.e., nullizygosity) may be linked to disease severity.

There is mounting evidence of genetic causes of MPN initiation and progression besides JAK2 and MPL, which define the MPN phenotype [21–28]. Deletion or mutation of TET2, associated with deletion and UPDs of chromosome 4q, have been reported in 10-12% of MPNs with or without JAK2 V617F [23, 28, 29]. Mutation of ASXL1 in CD34-positive purified cells strongly suggests that this is an early genetic event closely related to epigenetic status [24]. Ernst et al. [25] reported that EZH2, which encodes the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex (PRC2), is mutated in a subset of MPNs; EZH2 also influences stem cell renewal by epigenetic repression of genes involved in cell fate decisions. In contrast, mutation of IDH is frequently found in blast-phase MPNs [26]. Therefore, investigation of other oncogenic mutations in MPN patients and their associations with germline gene variants might help to reveal the mechanism underlying the relationship between haplotype variants and somatic mutability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the C allele of the JAK2 rs4495487 is an additional candidate locus that contributes to MPN predisposition in the Japanese population. Although the number of patients analyzed is too small to draw a definitive conclusion, our results provide novel insights into the molecular pathogenesis of MPNs. To clarify the pathophysiology of MPNs, it will be necessary to analyze JAK2 SNPs as a MPN predisposition, quantify JAK2 V617F mutations as a hallmark of MPN phenotype, and identify other germline variants and somatic mutations, including TET2, in a large number of patients.

References

Jones AV, Kreil S, Zoi K, Waghorn K, Curtis C, Zhang L, Score J, Seear R, Chase AJ, Grand FH, White H, Zoi C, Loukopoulos D, Terpos E, Vervessou EC, Schultheis B, Emig M, Ernst T, Lengfelder E, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Oscier D, Silver RT, Reiter A, Cross NC: Widespread occurrence of the JAK2 V617F mutation in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2005, 106 (6): 2162-2168. 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1320.

Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, Teo SS, Tiedt R, Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Cazzola M, Skoda RC: A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352 (17): 1779-1790. 10.1056/NEJMoa051113.

James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, Garcon L, Raslova H, Berger R, Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Villeval JL, Constantinescu SN, Casadevall N, Vainchenker W: A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005, 434 (7037): 1144-1148. 10.1038/nature03546.

Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, Boggon TJ, Wlodarska I, Clark JJ, Moore S, Adelsperger J, Koo S, Lee JC, Gabriel S, Mercher T, D'Andrea A, Fröhling S, Döhner K, Marynen P, Vandenberghe P, Mesa RA, Tefferi A, Griffin JD, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Lee SJ, Gilliland DG: Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005, 7 (4): 387-397. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023.

Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, Vassiliou GS, Bench AJ, Boyd EM, Curtin N, Scott MA, Erber WN, Green AR: Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9464): 1054-1061.

Tefferi A, Vardiman JW: Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia. 2008, 22 (1): 14-22. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404955.

Jones AV, Chase A, Silver RT, Oscier D, Zoi K, Wang YL, Cario H, Pahl HL, Collins A, Reiter A, Grand F, Cross NC: JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (4): 446-449. 10.1038/ng.334.

Kilpivaara O, Mukherjee S, Schram AM, Wadleigh M, Mullally A, Ebert BL, Bass A, Marubayashi S, Heguy A, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Offit K, Stone RM, Gilliland DG, Klein RJ, Levine RL: A germline JAK2 SNP is associated with predisposition to the development of JAK2(V617F)-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (4): 455-459. 10.1038/ng.342.

Olcaydu D, Harutyunyan A, Jager R, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pabinger I, Gisslinger H, Kralovics R: A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (4): 450-454. 10.1038/ng.341.

Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Gangat N, Wolanskyj AP, Hanson CA, Tefferi A: The JAK2 46/1 haplotype confers susceptibility to essential thrombocythemia regardless of JAK2V617F mutational status-clinical correlates in a study of 226 consecutive patients. Leukemia. 2010, 24 (1): 110-114. 10.1038/leu.2009.226.

Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Patnaik MM, Finke CM, Hussein K, Hogan WJ, Elliott MA, Litzow MR, Hanson CA, Pardanani A: JAK2 germline genetic variation affects disease susceptibility in primary myelofibrosis regardless of V617F mutational status: nullizygosity for the JAK2 46/1 haplotype is associated with inferior survival. Leukemia. 2010, 24 (1): 105-109. 10.1038/leu.2009.225.

Olcaydu D, Rumi E, Harutyunyan A, Passamonti F, Pietra D, Pascutto C, Berg T, Jager R, Hammond E, Cazzola M, Kralovics R: The role of the JAK2 GGCC haplotype and the TET2 gene in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2011, 96 (3): 367-374. 10.3324/haematol.2010.034488.

Jones AV, Campbell PJ, Beer PA, Schnittger S, Vannucchi AM, Zoi K, Percy MJ, McMullin MF, Scott LM, Tapper W, Silver RT, Oscier D, Harrison CN, Grallert H, Kisialiou A, Strike P, Chase AJ, Green AR, Cross NC: The JAK2 46/1 haplotype predisposes to MPL-mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010, 115 (22): 4517-4523. 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236448.

Ohyashiki K, Aota Y, Akahane D, Gotoh A, Ohyashiki JH: JAK2(V617F) mutational status as determined by semiquantitative sequence-specific primer-single molecule fluorescence detection assay is linked to clinical features in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Leukemia. 2007, 21 (5): 1097-1099.

Trifa AP, Cucuianu A, Petrov L, Urian L, Militaru MS, Dima D, Pop IV, Popp RA: The G allele of the JAK2 rs10974944 SNP, part of JAK2 46/1 haplotype, is strongly associated with JAK2 V617F-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Hematol. 2010, 89 (10): 979-983. 10.1007/s00277-010-0960-y.

Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Rambaldi A, Barosi G, Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Finazzi G, Guerini V, Fabris F, Randi ML, De Stefano V, Caberlon S, Tafuri A, Ruggeri M, Specchia G, Liso V, Rossi E, Pogliani E, Gugliotta L, Bosi A, Barbui T: Clinical profile of homozygous JAK2 617V > F mutation in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007, 110 (3): 840-846. 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064287.

Patriarca A, Pompetti F, Malizia R, Iuliani O, Di Marzio I, Spadano A, Dragani A: Is the absence of JAK2 mutation a risk factor for bleeding in essential thrombocythemia? An analysis of 106 patients. Blood Transfus. 2010, 8 (1): 21-27.

Colaizzo D, Tiscia GL, Bafunno V, Amitrano L, Vergura P, Lupone MR, Grandone E, Guardascione MA, Margaglione M: Sex modulation of the occurrence of jak2 v617f mutation in patients with splanchnic venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2011

Smalberg JH, Koehler E, Darwish Murad S, Plessier A, Seijo S, Trebicka J, Primignani M, de Maat MP, Garcia-Pagan JC, Valla DC, Randi ML, De Stefano V, Caberlon S, Tafuri A, Ruggeri M, Specchia G, Liso V, Rossi E, Pogliani E, Gugliotta L, Bosi A, Barbui T: The JAK2 46/1 haplotype in Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis. Blood. 2011, 117 (15): 3968-3973. 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319087.

Kouroupi E, Kiladjian JJ, Chomienne C, Dosquet C, Bellucci S, Valla D, Cassinat B: The JAK2 46/1 haplotype in splanchnic vein thrombosis. Blood. 2011, 117 (21): 5777-5778. 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343657.

Pardanani AD, Levine RL, Lasho T, Pikman Y, Mesa RA, Wadleigh M, Steensma DP, Elliott MA, Wolanskyj AP, Hogan WJ, McClure RF, Litzow MR, Gilliland DG, Tefferi A: MPL515 mutations in myeloproliferative and other myeloid disorders: a study of 1182 patients. Blood. 2006, 108 (10): 3472-3476. 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018879.

Steensma DP, Caudill JS, Pardanani A, McClure RF, Lasho TL, Tefferi A: MPL W515 and JAK2 V617 mutation analysis in patients with refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts and an elevated platelet count. Haematologica. 2006, 91 (12 Suppl): ECR57-

Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, James C, Trannoy S, Masse A, Kosmider O, Le Couedic JP, Robert F, Alberdi A, Lécluse Y, Plo I, Dreyfus FJ, Marzac C, Casadevall N, Lacombe C, Romana SP, Dessen P, Soulier J, Viguié F, Fontenay M, Vainchenker W, Bernard OA: Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360 (22): 2289-2301. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069.

Carbuccia N, Murati A, Trouplin V, Brecqueville M, Adelaide J, Rey J, Vainchenker W, Bernard OA, Chaffanet M, Vey N, Birnbaum D, Mozziconacci MJ: Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009, 23 (11): 2183-2186. 10.1038/leu.2009.141.

Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, Waghorn K, Zoi K, Ross FM, Reiter A, Hochhaus A, Drexler HG, Duncombe A, Cervantes F, Oscier D, Boultwood J, Grand FH, Cross NC: Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat genet. 2010, 42 (8): 722-726. 10.1038/ng.621.

Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Mai M, McClure RF, Tefferi A: IDH1 and IDH2 mutation analysis in chronic- and blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010, 24 (6): 1146-1151. 10.1038/leu.2010.77.

Sanada M, Suzuki T, Shih LY, Otsu M, Kato M, Yamazaki S, Tamura A, Honda H, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Kumano K, Oda H, Yamagata T, Takita J, Gotoh N, Nakazaki K, Kawamata N, Onodera M, Nobuyoshi M, Hayashi Y, Harada H, Kurokawa M, Chiba S, Mori H, Ozawa K, Omine M, Hirai H, Nakauchi H, Koeffler HP, Ogawa S: Gain-of-function of mutated C-CBL tumour suppressor in myeloid neoplasms. Nature. 2009, 460 (7257): 904-908. 10.1038/nature08240.

Tefferi A, Pardanani A, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, Gangat N, Finke CM, Schwager S, Mullally A, Li CY, Hanson CA, Mesa R, Bernard O, Delhommeau F, Vainchenker W, Gilliland DG, Levine RL: TET2 mutations and their clinical correlates in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2009, 23 (5): 905-911. 10.1038/leu.2009.47.

Klampfl T, Harutyunyan A, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Schalling M, Bagienski K, Olcaydu D, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Pietra D, Jäger R, Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Iacobucci I, Martinelli G, Cazzola M, Vannucchi AM, Gisslinger H, Kralovics R: Genome integrity of myeloproliferative neoplasms in chronic phase and during disease progression. Blood. 2011, 118 (1): 167-176. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331678.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/13/6/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ayako Hirota and Chiaki Kobayashi for their technical assistance. This work was funded by the Promotion of Science and Technology project for private universities, with a matching fund subsidy from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), 2009-2014, and by the University-Industry Joint Research Project for private universities with a matching fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JHO participated in the design and interpretation of the analysis, statistical analysis, and writing of the article. HH planned and coordinated the research. KO, TI, and UT collected samples from patients, and MY performed DNA sequencing and PCR analysis. KO helped to write the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2011_909_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: Primers used in this study. (A) Primers used for PCR-direct sequencing. Primers 1, 7, 8, 9, and 10 were also used for allele-specific PCR to discriminate JAK2 V617F-positive and -negative alleles. (B) Primers used for SNP analysis in 138 MPN patients and 107 healthy controls. (PDF 33 KB)

12881_2011_909_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2: Six SNPs of the JAK2 locus in PV patients and normal controls. Six SNPs were sequenced using allele-specific primers (Additional File 1A). In normal controls, detected SNPs were located in the allele without JAK2 V617F mutation. In PV patients, detected SNPs were located in the mutated T allele of JAK2. The genotype that had minor alleles in all six SNPs was designated as the GGTCAC genotype. This genotype is more frequently observed in T allele of JAK2 V617F (19/28, 67.9%) than G allele in normal controls (6/28, 21.4%); the odds ratio was 7.74 (95% CI: 2.32-25.75). There were no significant differences in age or sex between normal controls and patients with PV. (PDF 53 KB)

12881_2011_909_MOESM3_ESM.PDF

Additional file 3: JAK2SNP distribution in 9 patients with PMF. We could not statistically analyze the possible association between genotypes and clinical manifestations because of the small number of PMF patients in this single-institution study, however, results of genotypic analysis are shown in this table. (PDF 29 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohyashiki, J.H., Yoneta, M., Hisatomi, H. et al. The C allele of JAK2 rs4495487 is an additional candidate locus that contributes to myeloproliferative neoplasm predisposition in the Japanese population. BMC Med Genet 13, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-13-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-13-6