Abstract

Background

Observational studies and randomized trials have suggested that estrogens and/or progesterone may lower the risk for colorectal cancer. Inherited variation in the sex-hormone genes may be one mechanism by which sex hormones affect colorectal cancer, although data are limited.

Method

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding 3 hormone receptors (ESR1, ESR2, PGR) and 5 hormone synthesizers (CYP19A1 and CYP17A1, HSD17B1, HSD17B2, HSD17B4) among 427 women with incident colorectal cancer and 871 matched controls who were Caucasians of European ancestry from 93676 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women's Health Initiative Observational cohort. A total of 242 haplotype-tagging and functional SNPs in the 8 genes were included for analysis. Unconditional logistic regression with adjustment for age and hysterectomy status was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

We observed a weak association between the CYP17A1 rs17724534 SNP and colorectal cancer risk (OR per risk allele (A) = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.09-1.78, corrected p-value = 0.07). In addition, a suggestive interaction between rs17724534 and rs10883782 in 2 discrete LD blocks of CYP17A1 was observed in relation to colorectal cancer (empirical p value = 0.04). Moreover, one haplotype block of CYP19A1 was associated with colorectal cancer (corrected global p value = 0.02), which likely reflected the association with the tagging SNP, rs1902584, in the block.

Conclusion

Our findings offer some support for a suggestive association of CYP17A1 and CYP19A1 variants with colorectal cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that an increase in female hormones such as estrogens and progestin as a result of pregnancy or use of exogenous steroid hormones is associated with a lower risk for developing colorectal cancer [1–3]. In support of these findings, the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) estrogen plus progestin (E+P) clinical trial reported a 40% lower risk for colorectal cancer in the treatment group compared with the placebo group [4, 5]. By contrast, the other WHI estrogen-alone (E-alone) trial among hysterectomized women did not find a lower risk of colorectal cancer in the treatment group [6]. Two recent observational studies also reported no reduced risk for colorectal cancer incidence among postmenopausal women with higher circulating levels of estradiol and estrone [7, 8]. Findings from these studies seemingly suggest that progesterone, but not estrogen, may be the key candidate for risk reduction in colorectal cancer. Alternatively, the risk associated with sex hormones may be under genetic control, as these hormones bind to their respective receptors to exert biological actions in target tissues such as the colorectum. Genes responsible for sex-hormone synthesis and metabolism also affect changes in sex hormone concentrations, and variation in these genes may affect risk for disease development.

Few candidate-gene studies have evaluated variation in sex-hormone genes in relation to colorectal cancer risk and findings have been mixed. Some [9, 10] but not all [11, 12] studies reported a potential link between genetic variation in estrogen receptors and colorectal cancer development. To date, at least 3 phase-design genome-wide association scan (GWAS) studies of colorectal cancer have been undertaken, which identified several novel susceptibility loci mapping to 1q41, 3q26.2, 8q23.3, 8q24, 10p14, 12q13.13, 14q22.2, 15q13, 16q22.1, 18q21, 19q13.1, 20p12.3, and 20q13.33 [13–20]. However, none of these detected regions harbor genes involved in sex hormone synthesis or actions. Two of the nearest sex-hormone genes, HSD17B2 (16q24.1) and CYP19A1 (15q21.1), are at least 13 million basepairs (bp) distant from the GWAS loci. These observations suggest that the individual effect of hormone-related genes on colorectal cancer risk is not large enough to be detected at the genome-wide significance level (ie, p value <10-7 to 10-8). Although the association of colorectal cancer with sex hormone genes may be weak at an individual level, the overall association may be enhanced if the contributions attributable to individual loci are combined [21, 22]. In addition, the association of colorectal cancer risk with sex hormone genes may also be affected by potential modifiers such as hormone therapy (HT) use [10, 23] and BMI [24].

In this case-control study nested in a large cohort of postmenopausal women, we undertook a comprehensive evaluation of common and putative functional variants in the genes encoding estrogen and progesterone receptors (ESR1, ESR2, PGR) and enzymes responsible for critical steps in the conversion of progesterone or androgens to estrogens (CYP19A1 and CYP17A1) and in the formation of active estrogens (HSD17B1, HSD17B2, HSD17B4) in relation to colorectal cancer risk. We additionally tested the combined effects of multiple loci on colorectal cancer risk and evaluated effect modification by several risk modifiers on the association between sex hormone genes and disease risk.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a case-control study nested in the Women's Health Initiative Observational cohort (WHI-OS), a large, multifaceted study designed to advance our understanding of the determinants of major chronic diseases in 93,676 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years who were recruited at 40 different clinical centers across the United States between October 1, 1993 and December 31, 1998 [25]. At baseline, women provided informed consent and completed questionnaires regarding demographic and behavioral factors, medical history, and use of medications including HT. A physical examination was conducted that included measurements of height and weight and circumferences of the waist and hip. Blood samples were obtained following an overnight fast of at least 8 hours, and were immediately centrifuged and stored at -70°C.

Each year, participants were asked whether they had been newly diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Case status and detailed diagnosis were then confirmed through centralized review of all pathology reports, discharge and consultant summaries, operative and radiology reports, and tumor registry abstracts. As of September 12 2005, 472 women of European ancestry were identified with a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Controls were matched to cases with a ratio of 2:1 frequency on age at screening for participation in the WHI-OS at baseline, ethnicity, hysterectomy status, and prevalent conditions at baseline. A total of 24 (9 cases and 15 controls) with insufficient or lack of DNA were subsequently excluded from the analysis. We additionally excluded 16 women who had reported a cancer history at baseline, which yielded a total of 460 cases and 916 controls in the present analysis.

In our exploratory analysis, we examined whether the potential association of sex hormone genes and colorectal cancer might be generalized to other ethnic groups. We included 58 African Americans with a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer and 116 matched controls, all of whom were free of cancer history at baseline, from the WHI-OS for the analysis.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study, and the study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Brigham and Women's Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) selection

We first selected a set of tagging SNPs that capture common variation and linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure across each of the 8 hormone genes based on the studies from the Breast and Prostate Cohort Consortium project (BPC3), which has performed SNP discovery and dense genotyping to capture most common haplotype diversity in 70 American Caucasians (http://www.uscnorris.com/MECGenetics). The tagging SNPs, chosen from common SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 1% or greater among whites, predicted an R h 2 of 0.70 or greater between observed haplotypes and those predicted based on tagging SNP genotypes [26–30]. Altogether, 179 SNPs were selected from the 8 genes.

We next undertook a literature search to identify putative functional SNPs in the selected genes that had been associated with risk of cancers including colorectal cancer. Most of these chosen SNPs were either at coding (synonymous or nonsynonymous) or promoter regions. We identified a total of 17 SNPs from the CYP19A1, HSD17B4, ESR1, ESR2, and PGR genes.

To further enrich the gene density, we used the Tagger program implemented in Haploview software [31] to identify additional SNPs within the gene regions as well as 10-20kb upstream and downstream of each gene and forced in both the tagging SNPs identified by the BPC3 studies and the functional SNPs selected from the literature. The data source for tagging SNP selection was from the CEPH Utah residents with European ancestry in the International Hapmap Project on the National Center for Biotechnology Information Build 35 assembly available in July 2006 (http://www.hapmap.org). Selection of tagging SNPs was based on a pairwise correlation coefficient (r2) of 0.7 or greater between tagging SNPs and untyped SNPs and a MAF of 5% or greater in the CEPH population. As a result, we selected additional 76 tagging SNPs from the 8 genes (Table 1), yielding a total of 272 SNPs for subsequent genotyping.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from the buffy coat fraction of centrifuged blood using the QIAmp Blood Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Genotyping determination was performed with the Sequenom MassARRAY Genotyping system at the Partners Genotyping Facility (Boston, MA). Briefly, a multiplexed PCR and then a minisequencing reaction were performed in a single well. The size of reaction products was determined directly by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, yielding genotype information. Laboratory personnel were blinded to case-control status. Quality control (QC) of Sequenom Genotyping was carried out by repeating the genotyping on 66 duplicate samples with an average concordance rate of 99.7% in all typed SNPs. The average genotyping drop-out rates for all SNPs were 4.3%, ranged from 0.6% to 17.5%.

Statistical Analysis

Genotype quality and filtering were first performed using the genetic software, PLINK version 1.07 [32]. SNPs were excluded from further analysis if they had a MAF of <5% or deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) among control subjects (p < 0.001). We also excluded individuals with >20% of missing genotype data.

Genotyping data were then analyzed with unconditional logistic regression as implemented in PLINK to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as risk estimates for colorectal cancer in subjects with a linear (log-odds additive) scoring for 0, 1, or 2 copies of the minor allele of each SNP. The analyzed models were adjusted for age (continuous) and hysterectomy status (yes, no) to reflect our case-control matching design. An empirical p value was calculated that gave a pointwise estimate of the significance level of each SNP; a value of <0.05 was denoted statistical significance.

Haplotype blocks were constructed for gene regions tagging ≥1 SNP with an allelic association test p value of <0.05. We first examined pairwise LD among controls and determined the LD blocks for these SNPs using the 'solid spine of LD' algorithm implemented in Haploview. Haplotype frequency and expected haplotypes for each subject were then inferred based on the unphased genotype data using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm in PLINK. We used unconditional logistic regression to estimate haplotype-specific ORs with the rest of the haplotypes as the referents. Haplotypes with estimated frequency of <1% were excluded from the analysis. We also performed an omnibus test to obtain a global p value for each haplotype block.

The possible joint effects of variation in each of the 8 genes on colorectal cancer risk were evaluated using the set-based tests implemented in PLINK. Within each gene, the set-based tests first selected the best SNP based on test statistic followed by SNPs in order of decreasing statistical significance. The statistic for each set (or each gene) with selected SNPs is calculated by averaging the test statistics from the selected SNPs within each gene. In the present analysis, we allowed the PLINK to choose simultaneously up to 5 independent loci (r2<0.5) with each p-value below 0.2 and tested for statistical significance with 10,000 permutations.

We also assessed effect modifiers including age (<70, ≥70 years), BMI (<25, ≥25 kg/m2), HT use (current E-alone users, current E+P users, past, never), and physical activity (<median, ≥median METs/wk) on the genetic association with colorectal cancer risk. We performed unconditional logistic regression analysis according to these factors with adjustment for the covariates described above. We also performed a global likelihood ratio test with a comparison of the log likelihood of the two models with and without the interaction terms in SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

To control for comparisons for multiple SNPs (or haplotypes), we performed 10,000 permutations to generate a gene-specific (familywise) empirical p value for each SNP (or haplotype) and to determine how frequently the identified association would occur by chance. For each permutation, the case-control status was shuffled, and the maximum observed x2 test statistic was compared with the experimental test statistics for each SNP (or haplotype). As compared with the asymptotic testing, the permutation procedures are not restricted to the assumptions of normality and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and are unaffected by rare allele frequency and small sample sizes. We performed these permutations using the max(T) permutation option in PLINK. In addition, we calculated the false discovery rate (FDR) for the global tests of interaction analysis on each gene using SAS procedure PROC MULTTEST [33].

In the present analysis, power to detect associated SNPs of a MAF of 10% with relative risks of 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.7 would be 13%, 27%, 46%, and 80%, respectively, using a 2-sided test and a p value of 0.001.

Results

Twenty-two of the 272 SNPs were first removed because of an MAF of <5%. An additional 8 SNPs were excluded because the distribution of the genotypes deviated from HWE among controls (p < 0.001). The remaining 242 SNPs were included for further analysis (Additional file 1, Table S1). We also excluded 78 individuals with >20% of missing genotype data, resulting in a total of 1298 women in the present analysis.

Table 2 provides the comparison of baseline characteristics of colorectal cancer patients and control subjects. Compared with control subjects, cancer patients tended to be heavier, physically inactive, consumed fewer calories, and were less likely to receive screening exams. However, difference in distribution was not statistically significant between cases and controls with respect to current smoking, history of colon polyps, family history of colorectal cancer, alcohol intake, and current use of E-alone or E+P therapy.

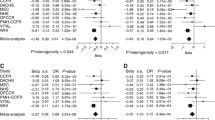

Among the 242 SNPs evaluated, rs10883782 and rs17724534 in CYP17A1, rs9340837 in ESR1, and rs1902584 in CYP19A1 were associated with colorectal cancer risk with an empirical p value of <0.05 (Table 3). When multiple comparisons were accounted for, only the CYP17A1 rs17724534 variant remained marginally significant (OR per copy of the risk allele (A) = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.08-1.78, corrected p-value = 0.07). There was no interaction between gene variants and BMI, types of HT, age, and physical activity in relation to colorectal cancer risk (corrected p values for interaction ≥0.14). There was also no association between gene variants and colorectal cancer risk according to tumor location and stage (data not shown).

Haplotype analysis was performed for the CYP17A1, CYP19A1, and ESR1 genes which included ≥1 SNP with an empirical p value of <0.05. The 5th block of the CYP19A1 gene, which contains the promoter region with 8 tagging SNPs including rs1902584, was significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk (corrected global p value = 0.02). Specifically, the TCCGCCGT (OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.34-0.7) and ATCGCTGT (OR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.13-2.01) haplotypes were associated with colorectal cancer risk (Additional file 2, Table S2). The LD blocks in CYP17A1 and ESR1 were not significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk (global p values ≥0.19).

We further evaluated the joint effects of independent loci on colorectal cancer risk. We found that the combined effects of rs10883782 and rs17724534 in CYP17A1 were significantly associated with colorectal cancer risk (empirical p value = 0.04). Around 24% of women carried ≥1 copy of the rs10883782 T allele and ≥1 copy of the rs17724534 A allele. Carriers who had both of these risk alleles were at a much greater risk of colorectal cancer (OR per copy of both risk alleles (T and A) = 4.60, 95% CI = 2.10-10.1). However, the LD for these 2 SNPs was low (r2 = 3%).

We also examined whether findings of the 4 SNPs with pointwise significance in Caucasians might also be present in African Americans. The risk allele, A, of the CYP17A1 rs1772453 SNP was rare (MAF = 3%) in this ethnic group, which was not associated with colorectal cancer risk. Similarly, there was no association with the rest 3 SNPs in this ethnic group (p values ≥0.32) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study of common and coding variation in 3 sex hormone receptors (ESR1, ESR2, PGR) and 5 hormone-synthesizing enzymes (CYP17A1, CYP19A1, HSD17B1, HSD17B2, HSD17B4) in relation to colorectal cancer risk among WHI-OS women of European ancestry, we observed suggestive evidence for an association with the rs17724534 SNP in CYP17A1. The association with colorectal cancer was more pronounced when the risk attributable to this SNP was combined with that of another SNP (rs10883782) in the same gene. In addition, an LD block in CYP19A1 which includes the promoter region was significantly associated with risk for colorectal cancer. There was, however, little evidence for an association of variation in other genes with colorectal cancer risk. The overall genetic association was also not affected by modifying factors including HT use, BMI, physical activity, and age. Moreover, the null association seen in African Americans is not surprising given that power is also very limited in this group of women.

The biological activity of estrogen signaling in the colon remains unclear. Several rodent and cell line studies have shown that estrogen-activated signaling through estrogen receptor alpha and/or estrogen receptor beta exhibits growth inhibition effects on colon cancer cells and loss of either receptors has been detected in colorectal cancer [34–38]. It has also been suggested that estrogen (ie, estradiol) upregulates mismatch repair genes in colonic epithelium cells which coordinate the repair of nucleotide base mismatches [39, 40]. However, other cell line studies have suggested the proliferative activity of estrogens in colon cancer cells [41, 42]. A recent study of human colon carcinoma has also reported that local synthesized concentrations of estrogens were 2-fold higher in colon carcinoma than those in adjacent normal colonic mucosa and were associated with adverse clinical outcome of the patients [43]. These observations suggest that estrogens may have dual effects on colorectal cancer development.

Little is known about the mechanism by which progesterone prevents colorectal carcinogenesis. It has been shown in cell lines that administration with progesterone at high concentrations resulted in inhibition of colon cancer growth [38]. In addition, a lower expression of PGR has been reported in tumors than in normal colorectal mucosa [44]. Progesterone may also enhance the estrogenic effects on cells [45] and inhibit the mitogenic activity of IGFs, possibly through the regulation of IGFBP1 [46–48].

Few candidate-gene studies have evaluated variation in hormone receptors (ESR1, ESR2, PGR) in relation to colorectal cancer risk [9–12]. Two studies have reported an association with ESR1 (rs9340799) and ESR2 (rs1255953) variants [9, 10], whereas our study along with two other studies [11, 12] did not observe such an association. As common variants likely confer a small risk for disease development [21, 22], studies with larger sample sizes than the current study may be required for the detection of significant association between sex hormone receptor genes and colorectal cancer [49]. In addition, our study may be underpowered to observe an association with variants in key enzymes involved in the formation of active estrogens (17beta-HSD families). Future large consortium studies may help shed light on the relationship between these gene variants and colorectal cancer.

The CYP17A1 gene encodes cytocrome P450C17alpha, an enzyme with 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities at key points in the biosynthesis of androgens and estrogens via progesterone [50]. A change of T→C variant (rs743572) located in the CYP17A1 promoter region has been found to create a SP1-type (CCACC) promoter site [51] and the C allele is associated with increased CYP17 expression levels [52, 53]. It has further been suggested that the CYP17A1 C allele is associated with enhanced production of all steroid hormones including progesterone and estrogen because of increased steroidogenesis in premenopausal women [54, 55], although the association is much weaker in postmenopausal women [56]. In agreement with a previous case-control study of middle-aged men and women [11], we did not find an association between this SNP and colorectal cancer risk. However, rs17724534, a neighboring SNP which is in LD with rs743572, was found to be suggestively associated with colorectal cancer risk. In this study population, all women who carried the rs17724534 A allele also had T allele of rs743572, suggesting that the rs17724534 A allele may be associated with lower progesterone and estrogen levels, leading to an increased risk for colorectal cancer.

We also observed a significant interaction between rs17724534 and rs10883782 in the CYP17A1 gene on colorectal cancer risk. The A allele of rs17724534 paired with T allele of rs10883782 were associated with a much greater risk for colorectal cancer as compared with other alleles. It is possible that the rs10883782 T allele enhanced the risk associated with the rs17724534 A allele on colorectal cancer development. To date, the functional relevance of rs10883782 to colorectal cancer risk is unknown, although it has been suggested that rs10883782 is near or within a region showing sequence homology to a CCAAT/enhancer protein, which is known to be a strong transcription regulator [57]. Both SNPs, which are 21.6k bp apart and not in LD, belong to 2 discrete haplotype blocks in this study population.

After menopause, estrogen biosynthesis takes place predominantly in adipose tissue and is catalyzed by the aromatase enzyme, encoded by the CYP19A1 gene, which converts androgens to estrogens. In the present study, a haplotype block (block #5 in our analysis) in CYP19A1 was associated with colorectal cancer, with 2 haplotypes reaching pointwise significance levels. The risk estimates in one haplotype (ATCGCTGT) were similar to those from the tagging SNP (rs1902584) in this block with the minor allele (A) showing an elevated risk for colorectal cancer, suggesting that the observed association with this haplotype block likely reflects that with rs1902584. The rs1902584 SNP is near the promoter 1.4 region that regulates the transcription of the aromatase gene [24, 58, 59], thereby affecting circulating hormone levels. It has been suggested that the minor allele genotypes (AT or AA) are associated with higher estrogen levels as compared with the homozygous major allele genotype (TT) in overweight postmenopausal women [60], suggesting a potential link between the minor allele (A) and elevated estrogens from the adiposity. It is possible that our finding of the associated increased risk for colorectal cancer with the minor allele may be attributable to obesity-induced elevation of estrogen levels. We, however, observed no effect modification by BMI on the association with this SNP, likely due to a lack of power.

There are several limitations of the present study. First, the genotyped SNPs may not sufficiently cover the entire gene regions. Although we have chosen a commonly used selection threshold (r2 ≥70%) for tagging SNP selection and have also included several functional SNPs, we cannot rule out the possibility that other untyped variants may contribute to the risk of developing colorectal cancer. In addition, the current data focused only on common SNPs without assessing the potential contributions of rare variants. However, if rare variants are to be discovered with an increase in sample size, it is possible that unidentified variants will have increasingly small effects [61]. Moreover, we may have limited statistical power for analysis of most of our candidate genes. Power is also limited in this study for subgroup analysis according to potential risk modifiers and tumor characteristics. Finally, we do not have information on which part of the European regions (eg, south vs. north) our samples were from, which may potentially confound the findings.

Conclusion

We observed little support for an association of gene variants in hormone receptors (ESR1, ESR2, PGR) and active estrogen synthesizers (HSD17B1, HSD17B2, and HSD17B4) with colorectal cancer risk among postmenopausal women of European descent. However, there is a suggestive evidence for an association with variation in CYP17A1 and CYP19A1. Our findings warrant confirmation in future studies.

References

La Vecchia C, Franceschi S: Reproductive factors and colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1991, 2 (3): 193-200. 10.1007/BF00056213.

Fernandez E, La Vecchia C, Balducci A, Chatenoud L, Franceschi S, Negri E: Oral contraceptives and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2001, 84 (5): 722-727. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1622.

Grodstein F, Newcomb PA, Stampfer MJ: Postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of colorectal cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 1999, 106 (5): 574-582. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00063-7.

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002, 288 (3): 321-333. 10.1001/jama.288.3.321.

Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, Ritenbaugh C, Hubbell FA, Ascensao J, Rodabough RJ, Rosenberg CA, Taylor VM, Harris R, Chen C, Adams-Campbell LL, White E: Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350 (10): 991-1004. 10.1056/NEJMoa032071.

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, et al: Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004, 291 (14): 1701-1712.

Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, Manson JE, Howard BV, Wylie-Rosett J, Anderson GL, Ho GY, Kaplan RC, Li J, Xue X, Harris TG, Burk RD, Strickler HD: Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, endogenous estradiol, and risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (1): 329-337. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2946.

Clendenen TV, Koenig KL, Shore RE, Levitz M, Arslan AA, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A: Postmenopausal levels of endogenous sex hormones and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18 (1): 275-281. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0777.

Speer G, Cseh K, Winkler G, Takacs I, Barna I, Nagy Z, Lakatos P: Oestrogen and vitamin D receptor (VDR) genotypes and the expression of ErbB-2 and EGF receptor in human rectal cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2001, 37 (12): 1463-1468. 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00139-3.

Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Murtaugh M, Ma KN, Wolff RK, Potter JD, Caan BJ, Samowitz W: Associations between ERalpha, ERbeta, and AR genotypes and colon and rectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (12): 2936-2942. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0514.

Bethke L, Webb E, Sellick G, Rudd M, Penegar S, Withey L, Qureshi M, Houlston R: Polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 genes CYP1A2, CYP1B1, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP11A1, CYP17A1, CYP19A1 and colorectal cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 2007, 7: 123-10.1186/1471-2407-7-123.

Lin J, Zee RY, Liu KY, Zhang SM, Lee IM, Manson JE, Giovannucci E, Buring JE, Cook NR: Genetic variation in sex-steroid receptors and synthesizing enzymes and colorectal cancer risk in women. Cancer Causes Control. 21 (6): 897-908.

Tomlinson I, Webb E, Carvajal-Carmona L, Broderick P, Kemp Z, Spain S, Penegar S, Chandler I, Gorman M, Wood W, Barclay E, Lubbe S, Martin L, Sellick G, Jaeger E, Hubner R, Wild R, Rowan A, Fielding S, Howarth K, Silver A, Atkin W, Muir K, Logan R, Kerr D, Johnstone E, Sieber O, Gray R, Thomas H, Peto J, et al: A genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for colorectal cancer at 8q24.21. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (8): 984-988. 10.1038/ng2085.

Zanke BW, Greenwood CM, Rangrej J, Kustra R, Tenesa A, Farrington SM, Prendergast J, Olschwang S, Chiang T, Crowdy E, Ferretti V, Laflamme P, Sundararajan S, Roumy S, Olivier JF, Robidoux F, Sladek R, Montpetit A, Campbell P, Bezieau S, O'Shea AM, Zogopoulos G, Cotterchio M, Newcomb P, McLaughlin J, Younghusband B, Green R, Green J, Porteous ME, Campbell H, et al: Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (8): 989-994. 10.1038/ng2089.

Tomlinson IP, Webb E, Carvajal-Carmona L, Broderick P, Howarth K, Pittman AM, Spain S, Lubbe S, Walther A, Sullivan K, Jaeger E, Fielding S, Rowan A, Vijayakrishnan J, Domingo E, Chandler I, Kemp Z, Qureshi M, Farrington SM, Tenesa A, Prendergast JG, Barnetson RA, Penegar S, Barclay E, Wood W, Martin L, Gorman M, Thomas H, Peto J, Bishop DT, et al: A genome-wide association study identifies colorectal cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 10p14 and 8q23.3. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (5): 623-630. 10.1038/ng.111.

Tenesa A, Farrington SM, Prendergast JG, Porteous ME, Walker M, Haq N, Barnetson RA, Theodoratou E, Cetnarskyj R, Cartwright N, Semple C, Clark AJ, Reid FJ, Smith LA, Kavoussanakis K, Koessler T, Pharoah PD, Buch S, Schafmayer C, Tepel J, Schreiber S, Volzke H, Schmidt CO, Hampe J, Chang-Claude J, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H, Wilkening S, Canzian F, Capella G, et al: Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on 11q23 and replicates risk loci at 8q24 and 18q21. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (5): 631-637. 10.1038/ng.133.

Jaeger E, Webb E, Howarth K, Carvajal-Carmona L, Rowan A, Broderick P, Walther A, Spain S, Pittman A, Kemp Z, Sullivan K, Heinimann K, Lubbe S, Domingo E, Barclay E, Martin L, Gorman M, Chandler I, Vijayakrishnan J, Wood W, Papaemmanuil E, Penegar S, Qureshi M, Farrington S, Tenesa A, Cazier JB, Kerr D, Gray R, Peto J, Dunlop M, et al: Common genetic variants at the CRAC1 (HMPS) locus on chromosome 15q13.3 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (1): 26-28. 10.1038/ng.2007.41.

Broderick P, Carvajal-Carmona L, Pittman AM, Webb E, Howarth K, Rowan A, Lubbe S, Spain S, Sullivan K, Fielding S, Jaeger E, Vijayakrishnan J, Kemp Z, Gorman M, Chandler I, Papaemmanuil E, Penegar S, Wood W, Sellick G, Qureshi M, Teixeira A, Domingo E, Barclay E, Martin L, Sieber O, Kerr D, Gray R, Peto J, Cazier JB, Tomlinson I, et al: A genome-wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (11): 1315-1317. 10.1038/ng.2007.18.

Houlston RS, Webb E, Broderick P, Pittman AM, Di Bernardo MC, Lubbe S, Chandler I, Vijayakrishnan J, Sullivan K, Penegar S, Carvajal-Carmona L, Howarth K, Jaeger E, Spain SL, Walther A, Barclay E, Martin L, Gorman M, Domingo E, Teixeira AS, Kerr D, Cazier JB, Niittymaki I, Tuupanen S, Karhu A, Aaltonen LA, Tomlinson IP, Farrington SM, Tenesa A, Prendergast JG, et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies four new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (12): 1426-1435. 10.1038/ng.262.

Houlston RS, Cheadle J, Dobbins SE, Tenesa A, Jones AM, Howarth K, Spain SL, Broderick P, Domingo E, Farrington S, Prendergast JG, Pittman AM, Theodoratou E, Smith CG, Olver B, Walther A, Barnetson RA, Churchman M, Jaeger EE, Penegar S, Barclay E, Martin L, Gorman M, Mager R, Johnstone E, Midgley R, Niittymaki I, Tuupanen S, Colley J, Idziaszczyk S, et al: Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13.33. Nat Genet. 42 (11): 973-977.

Easton DF, Eeles RA: Genome-wide association studies in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17 (R2): R109-115. 10.1093/hmg/ddn287.

Chung CC, Magalhaes W, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Chanock SJ: Genome-wide Association Studies in Cancer - Current and Future Directions. Carcinogenesis. 2009

Feigelson HS, McKean-Cowdin R, Pike MC, Coetzee GA, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, Le Marchand L, Henderson BE: Cytochrome P450c17alpha gene (CYP17) polymorphism predicts use of hormone replacement therapy. Cancer Res. 1999, 59 (16): 3908-3910.

Long JR, Shu XO, Cai Q, Wen W, Kataoka N, Gao YT, Zheng W: CYP19A1 genetic polymorphisms may be associated with obesity-related phenotypes in Chinese women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31 (3): 418-423. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803439.

Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998, 19 (1): 61-109.

Haiman CA, Stram DO, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Burtt NP, Altshuler D, Hirschhorn J, Henderson BE: A comprehensive haplotype analysis of CYP19 and breast cancer risk: the Multiethnic Cohort. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12 (20): 2679-2692. 10.1093/hmg/ddg294.

Pearce CL, Hirschhorn JN, Wu AH, Burtt NP, Stram DO, Young S, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Altshuler D, Pike MC: Clarifying the PROGINS allele association in ovarian and breast cancer risk: a haplotype-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005, 97 (1): 51-59. 10.1093/jnci/dji007.

Cox DG, Bretsky P, Kraft P, Pharoah P, Albanes D, Altshuler D, Amiano P, Berglund G, Boeing H, Buring J, Burtt N, Calle EE, Canzian F, Chanock S, Clavel-Chapelon F, Colditz GA, Feigelson HS, Haiman CA, Hankinson SE, Hirschhorn J, Henderson BE, Hoover R, Hunter DJ, Kaaks R, Kolonel L, LeMarchand L, Lund E, Palli D, Peeters PH, Pike MC, et al: Haplotypes of the estrogen receptor beta gene and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2008, 122 (2): 387-392.

Chen YC, Kraft P, Bretsky P, Ketkar S, Hunter DJ, Albanes D, Altshuler D, Andriole G, Berg CD, Boeing H, Burtt N, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Cann H, Canzian F, Chanock S, Dunning A, Feigelson HS, Freedman M, Gaziano JM, Giovannucci E, Sanchez MJ, Haiman CA, Hallmans G, Hayes RB, Henderson BE, Hirschhorn J, Kaaks R, Key TJ, Kolonel LN, LeMarchand L, et al: Sequence variants of estrogen receptor beta and risk of prostate cancer in the National Cancer Institute Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16 (10): 1973-1981. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0431.

Setiawan VW, Schumacher FR, Haiman CA, Stram DO, Albanes D, Altshuler D, Berglund G, Buring J, Calle EE, Clavel-Chapelon F, Cox DG, Gaziano JM, Hankinson SE, Hayes RB, Henderson BE, Hirschhorn J, Hoover R, Hunter DJ, Kaaks R, Kolonel LN, Kraft P, Ma J, Le Marchand L, Linseisen J, Lund E, Navarro C, Overvad K, Palli D, Peeters PH, Pike MC, et al: CYP17 genetic variation and risk of breast and prostate cancer from the National Cancer Institute Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16 (11): 2237-2246. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0589.

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21 (2): 263-265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81 (3): 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D: Quantitative trait Loci analysis using the false discovery rate. Genetics. 2005, 171 (2): 783-790. 10.1534/genetics.104.036699.

Campbell-Thompson M, Lynch IJ, Bhardwaj B: Expression of estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes and ERbeta isoforms in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (2): 632-640.

Qiu Y, Waters CE, Lewis AE, Langman MJ, Eggo MC: Oestrogen-induced apoptosis in colonocytes expressing oestrogen receptor beta. J Endocrinol. 2002, 174 (3): 369-377. 10.1677/joe.0.1740369.

Cho NL, Javid SH, Carothers AM, Redston M, Bertagnolli MM: Estrogen receptors alpha and beta are inhibitory modifiers of Apc-dependent tumorigenesis in the proximal colon of Min/+ mice. Cancer Res. 2007, 67 (5): 2366-2372. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3026.

Hartman J, Edvardsson K, Lindberg K, Zhao C, Williams C, Strom A, Gustafsson JA: Tumor repressive functions of estrogen receptor beta in SW480 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (15): 6100-6106. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0506.

Motylewska E, Melen-Mucha G: Estrone and progesterone inhibit the growth of murine MC38 colon cancer line. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009, 113 (1-2): 75-79. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.11.007.

Jin P, Lu XJ, Sheng JQ, Fu L, Meng XM, Wang X, Shi TP, Li SR, Rao J: Estrogen stimulates the expression of mismatch repair gene hMLH1 in colonic epithelial cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa). 3 (8): 910-916.

Slattery ML, Potter JD, Curtin K, Edwards S, Ma KN, Anderson K, Schaffer D, Samowitz WS: Estrogens reduce and withdrawal of estrogens increase risk of microsatellite instability-positive colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (1): 126-130.

Fiorelli G, Picariello L, Martineti V, Tonelli F, Brandi ML: Functional estrogen receptor beta in colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999, 261 (2): 521-527. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1062.

English MA, Kane KF, Cruickshank N, Langman MJ, Stewart PM, Hewison M: Loss of estrogen inactivation in colonic cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84 (6): 2080-2085. 10.1210/jc.84.6.2080.

Sato R, Suzuki T, Katayose Y, Miura K, Shiiba K, Tateno H, Miki Y, Akahira J, Kamogawa Y, Nagasaki S, Yamamoto K, Ii T, Egawa S, Evans DB, Unno M, Sasano H: Steroid sulfatase and estrogen sulfotransferase in colon carcinoma: regulators of intratumoral estrogen concentrations and potent prognostic factors. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (3): 914-922. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0906.

Di Leo A, Linsalata M, Cavallini A, Messa C, Russo F: Sex steroid hormone receptors, epidermal growth factor receptor, and polyamines in human colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992, 35 (4): 305-309. 10.1007/BF02048105.

Savouret JF, Misrahi M, Milgrom E: Molecular action of progesterone. Int J Biochem. 1990, 22 (6): 579-594. 10.1016/0020-711X(90)90033-Y.

Liu HC, He ZY, Mele C, Damario M, Davis O, Rosenwaks Z: Hormonal regulation of expression of messenger RNA encoding insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in human endometrial stromal cells cultured in vitro. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997, 3 (1): 21-26. 10.1093/molehr/3.1.21.

Suvanto-Luukkonen E, Sundstrom H, Penttinen J, Kauppila A, Rutanen EM: Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1: a biochemical marker of endometrial response to progestin during hormone replacement therapy. Maturitas. 1995, 22 (3): 255-262. 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00935-E.

Goldfine ID, Papa V, Vigneri R, Siiteri P, Rosenthal S: Progestin regulation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor I receptors in cultured human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992, 22 (1): 69-79. 10.1007/BF01833335.

Dunning AM, Healey CS, Baynes C, Maia AT, Scollen S, Vega A, Rodriguez R, Barbosa-Morais NL, Ponder BA, Low YL, Bingham S, Haiman CA, Le Marchand L, Broeks A, Schmidt MK, Hopper J, Southey M, Beckmann MW, Fasching PA, Peto J, Johnson N, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard B, Milne RL, Benitez J, Hamann U, Ko Y, Schmutzler RK, Burwinkel B, Schurmann P, et al: Association of ESR1 gene tagging SNPs with breast cancer risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2009, 18 (6): 1131-1139. 10.1093/hmg/ddn429.

Picado-Leonard J, Miller WL: Cloning and sequence of the human gene for P450c17 (steroid 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase): similarity with the gene for P450c21. DNA. 1987, 6 (5): 439-448. 10.1089/dna.1987.6.439.

Nedelcheva Kristensen V, Haraldsen EK, Anderson KB, Lonning PE, Erikstein B, Karesen R, Gabrielsen OS, Borresen-Dale AL: CYP17 and breast cancer risk: the polymorphism in the 5' flanking area of the gene does not influence binding to Sp-1. Cancer Res. 1999, 59 (12): 2825-2828.

Hopper JL, Hayes VM, Spurdle AB, Chenevix-Trench G, Jenkins MA, Milne RL, Dite GS, Tesoriero AA, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Southey MC: A protein-truncating mutation in CYP17A1 in three sisters with early-onset breast cancer. Hum Mutat. 2005, 26 (4): 298-302. 10.1002/humu.20237.

Miyoshi Y, Iwao K, Ikeda N, Egawa C, Noguchi S: Genetic polymorphism in CYP17 and breast cancer risk in Japanese women. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36 (18): 2375-2379. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00334-8.

Feigelson HS, Shames LS, Pike MC, Coetzee GA, Stanczyk FZ, Henderson BE: Cytochrome P450c17alpha gene (CYP17) polymorphism is associated with serum estrogen and progesterone concentrations. Cancer Res. 1998, 58 (4): 585-587.

Daneshmand S, Weitsman SR, Navab A, Jakimiuk AJ, Magoffin DA: Overexpression of theca-cell messenger RNA in polycystic ovary syndrome does not correlate with polymorphisms in the cholesterol side-chain cleavage and 17alpha-hydroxylase/C(17-20) lyase promoters. Fertil Steril. 2002, 77 (2): 274-280. 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02999-5.

Haiman CA, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, De Vivo I: A polymorphism in CYP17 and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (10): 3955-3960.

Douglas JA, Zuhlke KA, Beebe-Dimmer J, Levin AM, Gruber SB, Wood DP, Cooney KA: Identifying susceptibility genes for prostate cancer--a family-based association study of polymorphisms in CYP17, CYP19, CYP11A1, and LH-beta. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (8): 2035-2039. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0170.

Bulun SE, Sebastian S, Takayama K, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Shozu M: The human CYP19 (aromatase P450) gene: update on physiologic roles and genomic organization of promoters. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003, 86 (3-5): 219-224. 10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00359-5.

Zhao Y, Mendelson CR, Simpson ER: Characterization of the sequences of the human CYP19 (aromatase) gene that mediate regulation by glucocorticoids in adipose stromal cells and fetal hepatocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 1995, 9 (3): 340-349. 10.1210/me.9.3.340.

Cai H, Shu XO, Egan KM, Cai Q, Long JR, Gao YT, Zheng W: Association of genetic polymorphisms in CYP19A1 and blood levels of sex hormones among postmenopausal Chinese women. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008, 18 (8): 657-664. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fe3326.

McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, Hirschhorn JN: Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008, 9 (5): 356-369. 10.1038/nrg2344.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/12/78/prepub

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by grants CA123089 and CA126846 from the National Cancer Institute. The WHI program is funded by contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. We thank all WHI centers and their principal investigators for their participation in this research. We also thank Eduardo Pereira for help with data management.

The WHI investigators include: Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller. Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg; (Medical ResearchLabs, Highland Heights, KY, USA) Evan Stein; (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA) Steven Cummings. Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA) Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) Haleh Sangi-Haghpeykar; (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) JoAnn E Manson; (Brown University, Providence, RI, USA) Charles B Eaton; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA) Lawrence S Phillips; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) Shirley Beresford; (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA) Lisa Martin; (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor- UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA) Rowan Chlebowski; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR, USA) Erin LeBlanc; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA, USA) Bette Caan; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA) Jane Morley Kotchen; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC, USA) Barbara V Howard; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL, USA) Linda Van Horn; (Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA) Henry Black; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA, USA) Marcia L Stefanick; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY, USA) Dorothy Lane; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA) Cora E Lewis; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ, USA) Cynthia A Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA, USA) John Robbins; (University of California at Irvine, CA, USA) F Allan Hubbell; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA) Lauren Nathan; (University of California at San Diego, LaJolla/Chula Vista, CA, USA) Robert D Langer; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA) Margery Gass; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL, USA) Marian Limacher; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA) J David Curb; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA, USA) Robert Wallace; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA, USA) Judith Ockene; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA) Norman Lasser; (University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA) Mary Jo O'Sullivan; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA) Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA) Robert Brunner; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) Gerardo Heiss; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) Lewis Kuller; (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN, USA) Karen C Johnson; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA) Robert Brzyski; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) Gloria E Sarto; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) Mara Vitolins; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA) Michael S Simon. Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) Sally Shumaker.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JHL carried out the genetic analysis and drafted the manuscript. SMZ acquired the data. JHL, SMZ, JEM, BBC, and RTC participated in the design of the study. SMZ, PK, JEM, and MJG participated in analyses and interpretation of data. All authors have helped to draft the manuscript, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2011_810_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Characteristics of the 272 SNPs. Information on SNPs including gene name, location, alleles, and whether being included in the analysis. (DOC 555 KB)

12881_2011_810_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: Haplotype-based association of CYP19A1 with colorectal cancer risk among the Caucasians from the Women's Health Initiative-Observational Cohort. Results of haplotype analysis for the CYP19A1 gene. (DOC 86 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, J.H., Manson, J.E., Kraft, P. et al. Estrogen and progesterone-related gene variants and colorectal cancer risk in women. BMC Med Genet 12, 78 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-12-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-12-78