Abstract

Background

Human height is considered highly heritable and correlated with certain disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and cancer. Despite environmental influences, genetic factors are known to play an important role in stature determination. A number of genetic determinants of adult height have already been established through genome wide association studies.

Methods

To examine 51 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) corresponding to the 46 previously reported genomic loci for height in 8,184 European American children with height measurements. We leveraged genotyping data from our ongoing GWA study of height variation in children in order to query the 51 SNPs in this pediatric cohort.

Results

Sixteen of these SNPs yielded at least nominally significant association to height, representing fifteen different loci including EFEMP1-PNPT1, GPR126, C6orf173, SPAG17, Histone class 1, HLA class III and GDF5-UQCC. Other loci revealed no evidence for association, including HMGA1 and HMGA2. For the 16 associated variants, the genotype score explained 1.64% of the total variation for height z-score.

Conclusion

Among 46 loci that have been reported to associate with adult height to date, at least 15 also contribute to the determination of height in childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Height has been correlated with various disorders, including the observations that taller people are at a higher risk of developing cancer and shorter people are more likely to present with type 2 diabetes [1–3]. Determination of height in humans has long been considered to be largely influenced by genetic factors; indeed, twin and family studies have suggested that as much as 90% of variation in human height is genetically determined[4–8].

For many years, studies have attempted to identify genetic factors influencing human height in order to provide insights into human growth and development. Prior to 2007, genome-wide linkage and candidate-gene association studies had limited success in this regard; however, with the recent emergence of genome wide association (GWA) studies, tens of common genetics variants influencing height have now been uncovered, primarily in adults[9–14].

Weedon et al published the first GWA study of height using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500 K platform on nearly 5,000 individuals of self-reported European ancestry[9]. As a consequence, they observed association to common variation in the mobility group-A2 (HMGA2) oncogene. Follow-up analyses in approximately 19,000 more individuals (both adults and children) revealed strong replication of this observation. A subsequent GWA study uncovered another height locus, GDF5-UQCC, using data from the FUSION and SardiNIA cohorts[10].

These initial discoveries were followed by four meta-analyses with larger sample sizes, which collectively revealed 44 additional height loci [11–14]. However, some lack of overlap between the results of these GWA studies has been observed, which may be partly explained by the different statistical powers of the studies[15].

Although the causal variants at these loci have still to be elucidated, it has been shown that many of the implicated genes are involved in pathways influencing bone and cartilage development, including skeletal development signaling (PTCH1, HHIP, BMPs, GDF5), the extracellular matrix (ACAN, FBLN5, EFEMP1, ADAMTS17, ADAMTSL3), chromatin structure and regulation (DOT1L, SCMH1, HMGA2) and cell cycle regulation and mitosis (CDK6, ANAPC13, NCAPG)[15]. In addition, some of the loci were novel and are now a clear focus of attention in height biology.

In this study we aimed at examining these initial and meta-analysis findings that were previously reported to be genome wide significant in a large European American pediatric cohort with height measurements to determine the relative impact of these variants on childhood stature. For this purpose, we leveraged genotyping data from our ongoing GWA study of height variation in children.

Methods

Study population

All subjects were consecutively recruited from the Greater Philadelphia area from 2006 to 2009 at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and its Primary Care Centers. Our study cohort consisted of 8,184 children of European ancestry with height information. All subjects were biologically unrelated and were aged between 0 and 18 years old. The basic characteristics of the study subjects are outlined in Table 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Parental informed consent was given for each study participant for both the blood collection and subsequent genotyping.

Genotyping

We performed high throughput genome-wide SNP genotyping using either the Illumina Infinium™ II HumanHap550 or Human 610 BeadChip technology in the same manner as our center has reported previously[16]. The SNPs analyzed survived the filtering of the genome wide dataset for SNPs with call rates < 95%, minor allele frequency < 1%, missing rate per person < 2% and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P < 10-5.

Loci described from GWA studies published to date have been found using either the Affymetrix or Illumina platform. In the event a locus was reported using both the Illumina and Affymetrix arrays, we used the SNPs present on the Illumina array. In the event of a signal only being described on the Affymetrix array, we either already had that SNP on our Illumina array or we identified and used the best surrogate SNP available (see Additional file 1: Supplemental Table S1 for the surrogates employed).

Statistical analyses

From our database of heights for our multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) determined Caucasians, as previously described[17–19] and resulting in a low genomic inflation factor, we eliminated height outliers using 2% cutoff for each age category in order to remove potential measurement error. As height values vary widely across pediatric age groups and gender, we calculated the Z-scores using inverse-normal transformation for each age (one year bin) and gender category, and conducted association analysis with the Z-scores as the outcome variable.

We queried the data for the indicated SNPs in our pediatric samples. All statistical analyses were carried out using the software package plink[20]. By treating the Z-score for height as a quantitative trait, association analysis for each SNP was carried out using linear regression with the SNP included as an independent variable (coded as 0, 1, and 2, counting the number of minor alleles at the SNP).

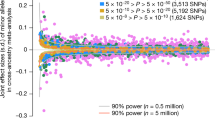

The results for Figure 1 were generated by summing the number of height increasing alleles across all 16 height-associated SNPs in our study to in order to produce a scatter plot showing the impact of the genotype score on the cumulative height Z-score.

Results

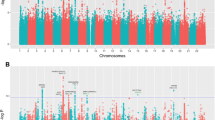

The 51 SNPs corresponding to the 46 previously reported height loci were investigated with respect to their association to normalized pediatric height in MDS-determined European Americans (Table 2; also Additional file 2: Supplemental Table S2 for analyses by age categories).

In summary, sixteen of these SNPs yielded at least nominally significant association to height (P < 0.05), representing fifteen different loci with the same direction of effect as previously reported. Of these fifteen loci, variation at the EFEMP1-PNPT1 locus yielded the strongest association with P = 1.39×10-5, namely rs3791679.

With a slightly lower magnitude of association was GPR126 with rs3748069 yielding a P = 3.64×10-4, C6orf173 (also known as LOC387103) with rs1490388 yielding a P = 7.20×10-4, SPAG17 with 118574711 yielding a P = 7.27×10-4 and the Histone class 1 gene cluster with rs10946808 yielding a P = 9.57×10-4.

Overall, in addition to these loci, we found evidence for association at the HLA class III region, UQCC-GDF5, C6orf106, JAZF1, ZBTB38, PLAG1, C1orf19-GLT25D2, LCORL-NCAPG, CABLES1-RBBP8-C18orf45 and SCMH1 loci. One could argue that we have carried out multiple testing in our height cohort for these previously reported SNPs, albeit at a number of magnitudes less than for a full GWA study. If we were to apply the strictest correction, i.e. the Bonferroni correction based on 51 SNPs, then EFEMP1-PNPT1, GPR126, C6orf173, SPAG17 and the Histone class 1 gene cluster would still be considered significant and their effects are consistent with the outcomes of the adult GWA studies.

It was also observed that SNPs residing at the 31 other loci did not reveal any evidence of association with height in our pediatric cohort, most notably HMGA2.

Finally, we investigated the sixteen significant SNPs further by testing for association between height Z-score and the genotype score, by summing the number of height increasing alleles across all these SNPs. The resulting P-value for the genotype score was < 2×10-16 (Figure 1). The genotype score explains 1.64% of the total variation for height z-score. We also tested pair-wise interactions between the sixteen significant SNPs, but none of the interaction effects were significant, suggesting that these sixteen SNPs act additively on pediatric height.

Discussion

We queried the existing dataset from our ongoing GWAS of pediatric height in European Americans for adult height loci uncovered in GWAS to date. We examined 51 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) corresponding to 46 genomic loci in 8,184 children with height measurements. Sixteen of these SNPs yielded at least nominally significant association to the trait, representing fifteen different loci.

One of the more notable results is the negative association with HMGA2. This gene is one of the most strongly associated loci with adult height[9] so its lack of association with childhood stature in this study is striking. We previously published a replication attempt with this locus and pediatric height when our cohort was substantially smaller[21]; at that time, we observed nominal association but it is clear that as our cohort has grown, this signal has failed to strengthen. Despite the wealth the evidence from adult GWA studies and from previous work with knock-out mouse models, it is of surprise not to observe association with HMGA2. However, when considering the age bins presented in Additional file 2: Supplemental Table S2, the T statistic generally increases with age, with the strongest value being for the 15-18 age group. Although none of these observations are significant, it may point to an age-specific effect at a particular point during childhood that is undetected in the overall analysis; however our large cohort size may still not be powered enough to tease out this effect.

For the loci we did not observe any evidence for association at all may be due to power issues, but could also indicate that they have a less pronounced role in a pediatric setting. In addition, only a portion of the published adult height loci have been independently and robustly replicated to date[22]. It should also be noted that childhood growth is an ongoing process where development factors may cloud detection at certain loci, including at the two rapid growth stages, where nutrition plays a major role in infant growth and hormone signaling impacts at puberty. Our study may lack power to detect stage specific association when using a mixed age childhood cohort; however we have presented the association results for specific age bins in Additional file 2: Supplemental Table S2.

From this analysis, it is clear that a number of loci previously reported from GWA analyses of adult height also play a role in our phenotype of interest. While these recently discovered loci unveil several new biomolecular pathways not previously associated with height, it is important to note that these well established genetic associations with stature explain very little of the genetic contribution for this pediatric phenotype, suggesting the existence of additional loci whose number and effect size remain unknown.

Conclusions

Among 46 loci that have been reported to associate with adult height to date, at least 15 also contribute to the determination of height in childhood. Once our GWA study is complete, we will have the opportunity to look for other variants in the genome that are associated with height in childhood.

References

Davey Smith G, Hart C, Upton M, Hole D, Gillis C, Watt G, Hawthorne V: Height and risk of death among men and women: aetiological implications of associations with cardiorespiratory disease and cancer mortality. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2000, 54 (2): 97-103. 10.1136/jech.54.2.97.

Gunnell D, Okasha M, Smith GD, Oliver SE, Sandhu J, Holly JM: Height, leg length, and cancer risk: a systematic review. Epidemiologic reviews. 2001, 23 (2): 313-342.

Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G: The association between components of adult height and Type II diabetes and insulin resistance: British Women's Heart and Health Study. Diabetologia. 2002, 45 (8): 1097-1106. 10.1007/s00125-002-0887-5.

Macgregor S, Cornes BK, Martin NG, Visscher PM: Bias, precision and heritability of self-reported and clinically measured height in Australian twins. Human genetics. 2006, 120 (4): 571-580. 10.1007/s00439-006-0240-z.

Preece MA: The genetic contribution to stature. Hormone research. 1996, 45 (Suppl 2): 56-58. 10.1159/000184849.

Silventoinen K, Kaprio J, Lahelma E, Koskenvuo M: Relative effect of genetic and environmental factors on body height: differences across birth cohorts among Finnish men and women. American journal of public health. 2000, 90 (4): 627-630. 10.2105/AJPH.90.4.627.

Silventoinen K, Kaprio J, Lahelma E, Viken RJ, Rose RJ: Sex differences in genetic and environmental factors contributing to body-height. Twin Res. 2001, 4 (1): 25-29. 10.1375/1369052012119.

Perola M, Sammalisto S, Hiekkalinna T, Martin NG, Visscher PM, Montgomery GW, Benyamin B, Harris JR, Boomsma D, Willemsen G, et al: Combined genome scans for body stature in 6,602 European twins: evidence for common Caucasian loci. PLoS genetics. 2007, 3 (6): e97-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030097.

Weedon MN, Lettre G, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Voight BF, Perry JR, Elliott KS, Hackett R, Guiducci C, Shields B, et al: A common variant of HMGA2 is associated with adult and childhood height in the general population. Nature genetics. 2007, 39 (10): 1245-1250. 10.1038/ng2121.

Sanna S, Jackson AU, Nagaraja R, Willer CJ, Chen WM, Bonnycastle LL, Shen H, Timpson N, Lettre G, Usala G, et al: Common variants in the GDF5-UQCC region are associated with variation in human height. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (2): 198-203. 10.1038/ng.74.

Weedon MN, Lango H, Lindgren CM, Wallace C, Evans DM, Mangino M, Freathy RM, Perry JR, Stevens S, Hall AS, et al: Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nature genetics. 2008, 40 (5): 575-583. 10.1038/ng.121.

Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Halldorsson BV, Zusmanovich P, Sulem P, Thorlacius S, Gylfason A, Steinberg S, et al: Many sequence variants affecting diversity of adult human height. Nature genetics. 2008, 40 (5): 609-615. 10.1038/ng.122.

Lettre G, Jackson AU, Gieger C, Schumacher FR, Berndt SI, Sanna S, Eyheramendy S, Voight BF, Butler JL, Guiducci C, et al: Identification of ten loci associated with height highlights new biological pathways in human growth. Nature genetics. 2008, 40 (5): 584-591. 10.1038/ng.125.

Soranzo N, Rivadeneira F, Chinappen-Horsley U, Malkina I, Richards JB, Hammond N, Stolk L, Nica A, Inouye M, Hofman A, et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans for human adult stature identifies novel Loci and associations with measures of skeletal frame size. PLoS genetics. 2009, 5 (4): e1000445-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000445.

Weedon MN, Frayling TM: Reaching new heights: insights into the genetics of human stature. Trends Genet. 2008, 24 (12): 595-603. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.09.006.

Hakonarson H, Grant SFA, Bradfield JP, Marchand L, Kim CE, Glessner JT, Grabs R, Casalunovo T, Taback SP, Frackelton EC, et al: A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007, 448 (7153): 591-594. 10.1038/nature06010.

Zhao J, Bradfield JP, Li M, Wang K, Zhang H, Kim CE, Annaiah K, Glessner JT, Thomas K, Garris M, et al: The Role of Obesity-associated Loci Identified in Genome-wide Association Studies in the Determination of Pediatric BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md. 2009, 17 (12): 2254-2257. 10.1038/oby.2009.159.

Zhao J, Bradfield JP, Zhang H, Annaiah K, Wang K, Kim CE, Glessner JT, Frackelton EC, Otieno FG, Doran J, et al: Examination of all type 2 diabetes GWAS loci reveals HHEX-IDE as a locus influencing pediatric BMI. Diabetes. 2010, 59 (3): 751-755. 10.2337/db09-0972.

Zhao J, Li M, Bradfield JP, Wang K, Zhang H, Sleiman P, Kim CE, Annaiah K, Glaberson W, Glessner JT, et al: Examination of type 2 diabetes loci implicates CDKAL1 as a birth weight gene. Diabetes. 2009, 58 (10): 2414-2418. 10.2337/db09-0506.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, et al: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics. 2007, 81 (3): 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

Grant SF, Li M, Bradfield JP, Kim CE, Annaiah K, Santa E, Glessner JT, Casalunovo T, Frackelton EC, Otieno FG, et al: Association of HMGA2 gene variation with height in specific pediatric age categories. Genomics Insights. 2008, 1: 13-16.

Lettre G: Genetic regulation of adult stature. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009, 21 (4): 515-522. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832c6dce.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/11/96/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participating subjects and families. Hope Thomas, Kisha Harden, Andrew Hill, Kenya Fain, Crystal Johnson-Honesty, Alex Moy, Cynthia Drummond, Shanell Harrison and Sarah Wildrick provided expert assistance with genotyping or data collection and management. We would also like to thank Smari Kristinsson, Larus Arni Hermannsson and Asbjörn Krisbjörnsson of Raförninn ehf for their extensive software design and contribution. This research was financially supported by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. The study is supported in part by a Research Development Award from the Cotswold Foundation (H.H. & S.F.A.G.) and NIH grant 1R01HD056465-01A1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JZ, HH and SFAG designed the study and supervised the data analysis and interpretation. JZ, ML, HZ and SFAG conducted the statistical analyses. CEK, CH, KAT, MLG, SD, ECF and FGO directed the genotyping and related sample handling. JPB, FDM, KW, PMS, JTG and BJG provided bioinformatics support. RMC and RIB coordinated the sample recruitment. JZ, ML, HH and SFAG drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jianhua Zhao, Mingyao Li contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2010_657_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional File 2: Supplemental Table S2: Quantitative association results for the candidate loci in the European American height cohort. Data is presented separately for age bins defined for under 2s, 2-5, 6-10, 11-14 and 15-18 year olds, sorted by chromosomal location. (DOC 558 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Li, M., Bradfield, J.P. et al. The role of height-associated loci identified in genome wide association studies in the determination of pediatric stature. BMC Med Genet 11, 96 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-96

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-96