Abstract

Background

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an alternative to diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for investigating biliary obstruction. The use of MRCP, a non-invasive procedure, may prevent the use of unnecessary invasive procedures. The aim of the study was to compare the findings of MRCP with those of ERCP by the computation of accuracy statistics.

Methods

Thirteen electronic bibliographic databases, covering biomedical, science, health economics and grey literature were searched. A systematic review of studies comparing MRCP to diagnostic ERCP in patients with suspected biliary obstruction was conducted. Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, acceptability and adverse events were reported.

Results

25 studies were identified reporting several conditions including choledocholithiasis (18 studies), malignancy (four studies), obstruction (three studies), stricture (two studies) and dilatation (five studies). Three of the 18 studies reporting choledocholithiasis were excluded from the analysis due to lack of data, or differences in study design. The sensitivity for the 15 studies of choledocholithiasis ranged from 0.50 to 1.00 while specificity ranged from 0.83 to 1.00. The positive likelihood ratio ranged: from 5.44–47.72 and the negative likelihood ratio for the 15 studies ranged from 0.00–0.51. Significant heterogeneity was found across the 15 studies so the sensitivities and specificities were summarised by a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. For malignancy, sensitivity ranged from 0.81 to 0.94 and specificity from 0.92 to 1.00. Positive likelihood ratios ranged from 10.12 to 43 and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0.15 to 0.21, although these estimates were less reliable.

Conclusion

MRCP is a comparable diagnostic investigation in comparison to ERCP for diagnosing biliary obstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biliary obstruction may be due to a variety of causes including choledocholithiasis, tumours, and trauma, including injury after gall bladder surgery, with choledocolithiasis being the most common cause. The prevalence of gallstones in England and Wales was 182 per 10,000 person years at risk. The incidence rate was 8 per 10,000 person years at risk for 1991–1992 [1]. Patients with suspected biliary obstruction present with abnormal liver function and symptoms such as jaundice, pale-coloured stools, dark urine, itching, abdominal pain in the upper right quadrant, fever, nausea and vomiting. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is the first-line imaging investigation in patients with jaundice or right upper-quadrant pain [2]. Although EUS is non-invasive, quick and inexpensive it is very operator and patient dependent.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is currently the 'gold standard' for the diagnosis of biliary obstruction. It is one of several invasive direct cholangiography techniques. However, it is an imperfect diagnostic tool and other procedures may be more appropriate gold standards for diagnosis in the future [3]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an alternative to diagnostic ERCP for imaging the biliary tree and investigating biliary obstruction. MRCP was developed in 1991 and techniques are continuing to improve. A major feature of MRCP is that it is not a therapeutic procedure, while in contrast ERCP is used for both diagnosis and treatment. MRCP also does not have the small but definite morbidity and mortality associated with ERCP. The use of MRCP in diagnosing biliary obstruction may avoid the use of unnecessary invasive procedures such as ERCP.

Indications for the use of MRCP include: unsuccessful or contraindicated ERCP; patient preference for non-invasive imaging; patients considered to be at low risk of having pancreatic or biliary disease; patients where the need for therapeutic ERCP is considered unlikely; and those with a suspected neoplastic cause for pancreatic or biliary obstruction [4]. No patient preparation is required for MRCP and sedation is not usually required. MRCP is particularly useful where ERCP is difficult, hazardous or impossible. It is also an important option for patients with failed ERCPs. ERCP and MRCP have different contraindications allowing them to be used as complementary techniques.

In order to determine the sensitivity and specificity of MRCP compared to ERCP, a systematic review was undertaken to identify all relevant studies comparing the two techniques using clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This paper therefore compares the findings of MRCP with diagnostic ERCP for the investigation of biliary obstruction, using accuracy statistics. We also report study quality, population characteristics and suspected conditions. The paper summarises the key clinical points reported in a recent Health Technology Assessment Monograph [5]. Since the most common cause of biliary obstruction is choledocholithiasis, we have concentrated mainly on the diagnosis of this condition.

Methods

We searched 13 electronic databases Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register from inception to January 2003. Reference lists of relevant articles were hand searched and various health services research-related resources were consulted via the Internet. Search terms included population search terms such as biliary, biliary tract, bile, gallbladder, choledocholithiasis and were combined with intervention terms such as magnetic resonance imaging, MRI and non-invasive diagnostic imaging. The search strategy is described in detail elsewhere [5]. No language or study/publication-type restrictions were applied to the searches. Inclusion criteria were adult patients with suspected biliary obstruction or dilatation, as defined by the individual studies, having MRCP and ERCP for diagnostic purposes. Outcome measures included sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios in different patient groups, acceptability to patients and adverse effects. The ERCP test results were assumed to be a true 'gold standard' diagnosis, although even the results of this test may be subject to error and thus not represent the patient's true condition. Only English language papers were selected. Studies involving pancreatic ductal system abnormalities were excluded, as were those not including a comparison of MRCP with diagnostic ERCP. Other exclusion criteria were: papers published before 1995; comparison of MRCP with failed or unsuccessful ERCP; studies where MRCP results informed decision to proceed to ERCP; and retrospective study design. Excluded studies were documented together with reasons for exclusion [5]. Data was extracted by one researcher using a standardised data extraction form and checked by another. Full details of the review process are described elsewhere [5].

The studies were assessed using quality criteria for diagnostic or screening tests [6]. These criteria include 14 components of study quality such as: appropriate spectrum of patients, selection criteria, independent assessment of test results, verification bias (whether all patients had both tests), reporting of uninterpretable results and withdrawals among others.

Standard tests for heterogeneity were conducted [7]. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for summary statistics (sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio) were calculated for each study and presented graphically with forest plots. In meta-analyses of diagnostic results one must also consider variation introduced by changes in the diagnostic threshold; studies may use different thresholds to define positive and negative test results. In the event of heterogeneity and/or variation in the diagnostic threshold, studies were summarised graphically with a Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (SROC) curve and via the Littenberg and Moses (L-M) method for estimation of a best fitting SROC curve [8]. The L-M method consists of linear regression of the log diagnostic odds ratio, D, against the log of the measure of diagnostic threshold S, to produce estimates of the parameters a and b from the regression equation, D = a + bS. D and S are calculated from the true positive and false positive rates. We computed the sensitivity and specificity values from the SROC at the mean, minimum and maximum values of the S parameter, to indicate a central value and associated band with which the data were compatible.

Results

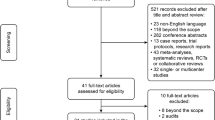

Out of a total of 1437 potentially relevant studies, 28 studies were identified that directly compared MRCP with diagnostic ERCP [9–36]. An additional study was identified that covered patient satisfaction [37]. Study selection is outlined in Figure 1. The quality of studies was variable. Results are shown in Table 1.

In only one study did all selected patients have both MRCP and diagnostic ERCP [31], indicating potential verification bias. Thirteen studies [10–12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 25, 28–30, 34, 36] reported adequate blinding and only six [10, 18, 22, 27, 29, 34] reported information on agreement of MRCP results for more than one investigator. Nine studies [10, 12, 17, 20, 22, 25, 28, 29, 32] gave no information on other diagnostic tests and most studies did not adequately report inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Seven studies [9, 17, 21, 22, 25, 26, 34], reported results comparing MRCP to final diagnosis (including ERCP and other test results) but only four of these reported data comparing MRCP with final diagnosis and ERCP with final diagnosis. The remaining 21 reported results comparing MRCP with diagnostic ERCP. Three [10, 17, 19] of the 28 studies did not provide enough information to calculate sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios. Accuracy was assessed separately for each condition (choledocolithiasis, malignancy, dilatation, obstruction and stricture). The results of the remaining 25 studies are shown in Table 2. Table 3 describes study characteristics. Studies comparing MRCP and ERCP with final diagnosis are shown in Table 4.

Assessment of effectiveness by condition: choledocolithiasis

One of the most common causes of biliary obstruction is choledocolithiasis: indeed 18 out of the 28 studies (64%) were for this condition. For this reason we concentrate mainly on the analysis of these studies. Of the 18 studies reporting results for choledocolithiasis, 15 [11, 13–15, 18, 20, 21, 26, 27, 29–31, 33, 35, 36] reported adequate data for analysis. Figure 2 shows a scatterplot of sensitivity vs. specificity for the 15 studies reporting choledocholithiasis.

Two of these studies stand out as having sensitivities somewhat lower than the other 13 studies [11, 36]. Sensitivities and specificities along with 95% CI for these estimates for the 15 choledocholithiasis studies are presented in Figures 3 and 4.

The sensitivity for the 15 studies of choledocholithiasis ranged from 0.50 to 1.00 while specificity ranged from 0.83 to 1.00. The positive likelihood ratio ranged from 5.44–47.72 and the negative likelihood ratio for the 15 studies ranged from 0.00–0.51. All of the confidence intervals overlap, although the confidence intervals for some studies are wide. Again two studies [11, 36] have point estimates in Figure 2 that are clearly different from the other 13 studies, suggesting that theses two studies are outliers. There is also some evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity between studies, (Figure 3 and 4), which suggested that the computation of a SROC curve was the most appropriate way to pool the results of studies.

Summary ROC curves for diagnosis of choledocholithiasis

Figure 2 also shows the parameter estimates and the results of the Littenberg-Moses method for the estimation of a summary best fitting ROC curve. This curve shows the relationship between sensitivities and specificities across the 15 studies. The non-significant result for the S coefficient estimate of 0.057 [CI: -0.25 to 0.42; p = 0.506], suggests that there is no reliable statistical evidence that the diagnostic odds ratio changes with threshold.

There is no unique joint summary estimate of sensitivity and specificity suitable for use in clinical practice from this plot. Table 5 shows values of sensitivity and specificity off the fitted ROC curve to demonstrate the range of values that the data are compatible with.

Assessment of effectiveness by other conditions: malignancy, dilatation, obstruction and stricture

For malignancy (three studies [9, 18, 22]), sensitivity ranged from 0.81 to 0.94 and specificity from 0.92 to 1.00. Positive likelihood ratios ranged from 10.12 to 43 and negative likelihood ratios ranged from 0.15 to 0.21. Although, from the results presented in Table 2 it is apparent that the results for malignancy are much less reliable than those for the other conditions presented. The sensitivity for dilatation (five studies [11, 12, 20, 25, 28]) ranged from 0.87 to 1.00 and the specificity from 0.91 to 1.00. For obstruction (three studies [11, 18, 27]), sensitivity ranged from 0.91 to 1.00 and specificity from 0.91 to 1.00. Sensitivity for stricture (two studies [24, 33]) was 1.00 and specificity ranged from 0.98 to 0.99.

Adverse events and satisfaction with procedures

None of the 28 studies reported any adverse events associated with MRCP. Six studies [9, 11, 13, 27, 31, 34] reported adverse effects associated with ERCP, including pancreatitis, bleeding and pain. Two [10, 15] reported that no adverse events had occurred and 20 gave no information at all regarding adverse events. Claustrophobia associated with MRCP was reported in ten studies [9, 11, 16, 18, 19, 24, 26, 27, 30, 33].

The separate study [37] dealing with patient satisfaction found that most patients preferred MRCP, although there were still some patients who preferred ERCP. Almost half of the patients in this small study complained of claustrophobia associated with MRCP, although very few (5.9%) refused MRCP for this reason.

Discussion

This systematic review shows that there is evidence that MRCP stands up well to comparisons with diagnostic ERCP, for the diagnosis of many biliary abnormalities. From the small number of comparative studies with final diagnosis, it appears that ERCP is an adequate reference standard for choledocholithiasis with sensitivities and specificities above 89%, however the results for malignancy were much less reliable. The limited evidence on patient satisfaction shows that patients prefer MRCP to diagnostic ERCP. The results of our review are similar to those found by Romagnuolo et al [38] who in their meta-analysis showed high levels of sensitivity and specificity for demonstrating the level and presence of biliary obstruction.

The main advantage of MRCP is that diagnostic ERCP may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality [39]. Reported complication rates of diagnostic ERCP are 5–6% and mortality figures range from 0.01% (36) to 0.89% [40]. Therapeutic ERCP has a complication rate of 4–10% [41]. Diagnostic ERCP has the potential to allow a therapeutic procedure to be performed immediately, but its indiscriminate use will result in an increasing proportion of patients in whom such intervention is found to be unnecessary. If preliminary tests, such as EUS or computed tomography, clearly indicate the need for therapeutic ERCP, then the use of diagnostic MRCP is probably unwarranted. Those patients with a high probability of choledocholethiasis on the basis of EUS investigations usually proceed directly to ERCP. These issues are elaborated in Bravo et al [42].

There were no reported adverse events associated with MRCP, other than claustrophobia. However, in certain circumstances MRCP cannot be performed due to contraindications to Magnetic Resonance Imaging, e.g. in patients with cardiac pacemakers or cochlear implants. Severe claustrophobia may make patients intolerant of the procedure.

Limitations of this study

Overall the quality of the studies was variable. In only one study did all selected patients have both MRCP and diagnostic ERCP. The reasons why all patients in the other studies did not receive both investigations were not clear. In 21 of the studies, the stated comparison was with ERCP, while in the other seven studies, comparison was with final diagnosis; making comparisons between all studies difficult.

We can consider three ways of categorising a patient: their true condition, the diagnosis and the test results [43]. We have calculated the sensitivity and specificity of MRCP in relationship to diagnosis by ERCP, but we do not necessarily know that the diagnosis is always correct. ERCP is not a perfect gold standard, so differences in diagnosis between MRCP and ERCP may not be due to MRCP giving an incorrect result, but rather to ERCP giving an incorrect result. So we have evaluated MRCP's ability to predict the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis rather than the patient's true disease status. So any errors in the ERCP reference test may lead to either underestimates or overestimates of MRCP's accuracy.

There are several problems associated with using summary ROC curves. For example, although the production of a summary ROC curve does allow the computation of a summary estimate of diagnostic performance, the results cannot be directly applied to clinical practice.

Our results indicate that MRCP is accurate for diagnosis of biliary abnormalities compared to diagnostic ERCP, within the limits of the available data. Good quality studies, particularly randomised controlled trials (we found no comparative clinical trials of the two techniques in our review), are needed comparing MRCP with diagnostic ERCP to final diagnosis, stating inclusion/exclusion criteria and relevant patient characteristics. These studies need to include the full range of target conditions, in particular the differentiation of benign and malignant strictures and the impact on management and outcome. Studies are also needed comparing MRCP with final diagnosis where ERCP is unsuitable or impossible. More research is also needed in the area of patient satisfaction and ways to reduce problems with claustrophobia.

Conclusion

MRCP is a comparable diagnostic investigation in comparison to ERCP for diagnosing biliary abnormalities. Results were particularly favourable for choledocholethiasis and less so for malignancy. Limited information on patient satisfaction found that patients prefer MRCP to ERCP. The use of MRCP in suitable patients reduces the need for diagnostic ERCP which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Abbreviations

- DOR:

-

diagnostic odds ratio

- ERCP:

-

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- L-M:

-

Littenberg and Moses

- MRCP:

-

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve

- SROC:

-

Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic curve

References

RCGP, OPCS, DHSS: Morbidity Statistics from General Practice Fourth national study 1991–1992. 1995, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, editor. Series MB5 no.3. London, HMSO

Kim JH, Kim MJ, Park SI, Chung JJ, Song SY, Kim KS, Yoo HS, Lee JT, Kim KW: MR cholangiography in symptomatic gallstones: diagnostic accuracy according to clinical risk group. Radiology. 2002, 224: 410-416.

Sheridan MB: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography should no longer be used as a diagnostic test: the case in favour. Digestive & Liver Disease. 2002, 34: 370-374. 10.1016/S1590-8658(02)80132-3.

Coakley FV, Qayyum A: Magnetic resonancecholangiopancreatography. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2002, 55 (7 Suppl): S2-12. 10.1067/mge.2002.124751.

Kaltenthaler E, Bravo Vergel Y, Chilcott J, Thomas S, Blakeborough A, Walters SJ, Bouchier H: A systematic review and economic evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography compared with diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Health Technology Assessment. 2004, 8 (10): 1-102. [http://www.ncchta.org/ProjectData/3_project_record_published.asp?PjtId=1355]

Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J: The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 3 (1): 25-10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. Nov 10 2003

Deeks JJ: Systematic reviews of evaluations of diagnostic and screening tests. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in context. Edited by: Eggers M Davey, Smith G, Altman D. 2001, London: BMJ Publishing Group, 248-82. 2

Littenberg B, Moses LE: Estimating diagnostic accuracy from multiple conflicting reports: a new meta-analytical method. Med Decision Making. 1993, 13: 313-321.

Adamek HE, Albert J, Weitz M, Breer H, Schilling D, Riemann JF: A prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with suspected bile duct obstruction. Gut. 1998, 43 (5): 680-683.

Alcaraz MJ, De la Morena EJ, Polo A, Ramos A, De la Cal MA, Gonzalez MA: A comparative study of magnetic resonance cholangiography and direct cholangiography. Revista Espaňola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2000, 92 (7): 427-438.

Angulo P, Pearce DH, Johnson CD, Henry JJ, LaRusso NF, Petersen BT, Lindor KD: Magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with biliary disease: its role in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2000, 33 (4): 520-527. 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x.

Barish MA, Yucel EK, Soto JA, Chuttani R, Ferrucci JT: MR cholangiopancreatography: efficacy of three-dimensional turbo spin-echo technique. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1995, 165 (2): 295-300.

Calvo MM, Bujanda L, Calderon A, Heras I, Cabriada JL, Bernal A, Orive V, Capelastegi A: Role of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with suspected choledocholithiasis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2002, 77 (5): 422-428.

Chan YL, Chan AC, Lam WW, Lee DW, Chung SS, Sung JJ, Cheung HS, Li AKC, Metreweli C: Choledocholithiasis: comparison of MR cholangiography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Radiology. 1996, 200 (1): 85-89.

Demartines N, Eisner L, Schnabel K, Fried R, Zuber M, Harder F: Evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the management of bile duct stones. Archives of Surgery. 2000, 135 (2): 148-152. 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.148.

Dwerryhouse SJ, Brown E, Vipond MN: Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiography to detect common bile duct stones before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. British Journal of Surgery. 1998, 85 (10): 1364-1366. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00957.x.

Feldman DR, Kulling DP, Kay CL, Cole DJ, Cunningham JT, Hawes RH, Tarnasky PR, Cotton PB, Baron PL: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: a novel approach to the evaluation of suspected pancreaticobiliary neoplasms. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1997, 4 (8): 634-638. 10.1007/BF02303747.

Guibaud L, Bret PM, Reinhold C, Atri M, Barkun AN: Bile duct obstruction and choledocholithiasis: diagnosis with MR cholangiography. Radiology. 1995, 197 (1): 109-115.

Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W, Abou-Rebyeh H, Hammerstingl R, Vogl T, Felix R: Clinical significance of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) compared to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Endoscopy. 1997, 29 (3): 182-187.

Holzknecht N, Gauger J, Sackmann M, Thoeni RF, Schurig J, Holl J, Weinzierl M, Helmberger T, Paumgartner G, Reiser M: Breath-hold MR cholangiography with snapshot techniques: prospective comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Radiology. 1998, 206 (3): 657-664.

Laokpessi A, Bouillet P, Sautereau D, Cessot F, Desport JC, Le Sidaner A, Pillegand B: American Value of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the preoperative diagnosis of common bile duct stones. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001, 96 (8): 2354-2359. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04045.x.

Lee MG, Lee HJ, Kim MH, Kang EM, Kim YH, Lee SG, Kim PN, Ha HK, Auh YH: Extrahepatic biliary diseases: 3D MR cholangiopancreatography compared with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1997, 202 (3): 663-669.

Lomanto D, Pavone P, Laghi A, Panebianco V, Mazzocchi P, Fiocca F, Lezoche E, Passariello R, Speranza V: Magnetic resonance-cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of biliopancreatic diseases. American Journal of Surgery. 1997, 174 (1): 33-38. 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00022-6.

Lomas DJ, Bearcroft PW, Gimson AE: MR cholangiopancreatography: prospective comparison of a breath-hold 2D projection technique with diagnostic ERCP. European Radiology. 1999, 9 (7): 1411-1417. 10.1007/s003300050859.

Macaulay SE, Schulte SJ, Sekijima JH, Obregon RG, Simon HE, Rohrmann CAJ, Freeny PC, Schmiedl UP: Evaluation of a non-breath-hold MR cholangiography technique. Radiology. 1995, 196: 1-232.

Regan F, Fradin J, Khazan R, Bohlman M, Magnuson T: Choledocholithiasis: evaluation with MR cholangiography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1996, 167: 1441-1445.

Reinhold C, Taourel P, Bret PM, Cortas GA, Mehta SN, Barkun AN, Wang L, Tafazoli F: Choledocholithiasis: evaluation of MR cholangiography for diagnosis. Radiology. 1998, 209 (2): 435-442.

Soto JA, Barish MA, Yucel EK, Siegenberg D, Ferrucci JT, Chuttani R: Magnetic resonance cholangiography: comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterology. 1996, 110 (2): 589-597. 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566608.

Soto JA, Barish MA, Alvarez O, Medina S: Detection of choledocholithiasis with MR cholangiography: comparison of three-dimensional fast spin-echo and single- and multisection half-Fourier rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement sequences. Radiology. 2000, 215 (3): 737-745.

Soto JA, Alvarez O, Munera F, Velez SM, Valencia J, Ramirez N: Diagnosing bile duct stones: comparison of unenhanced helical CT, oral contrast-enhanced CT cholangiography, and MR cholangiography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2000, 175 (4): 1127-1134.

Stiris MG, Tennoe B, Aadland E, Lunde OC: MR cholangiopancreaticography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography in patients with suspected common bile duct stones. Acta Radiologica. 2000, 41 (3): 269-272. 10.1080/028418500127345226.

Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, Hanaoka H, Mizutani Y, Hachiya J: Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Surgery. 1998, 123 (4): 391-397.

Taylor AC, Little AF, Hennessy OF, Banting SW, Smith PJ, Desmond PV: Prospective assessment of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for noninvasive imaging of the biliary tree. GASTROINTEST ENDOSC. 2002, 55 (1): 17-22. 10.1067/mge.2002.120324.

Textor HJ, Flacke S, Pauleit D, Keller E, Neubrand M, Terjung B, Gieseke J, Scheurlen C, Sauerbruch T, Schild HH: Three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with respiratory triggering in the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis: comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Endoscopy. 2002, 34 (12): 984-990. 10.1055/s-2002-35830.

Varghese JC, Liddell RP, Farrell MA, Murray FE, Osborne DH, Lee MJ: Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and ultrasound compared with direct cholangiography in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Clinical Radiology. 2000, 55 (1): 25-35. 10.1053/crad.1999.0319.

Zidi SH, Prat F, Le Guen O, Rondeau Y, Rocher L, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Pelletier G: Use of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis: prospective comparison with a reference imaging method. Gut. 1999, 44 (1): 118-122.

Menon K, Barkun AN, Romagnuolo J, Friedman G, Mehta SN, Reinhold C, Bret PM: Patient satisfaction after MRCP and ERCP. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001, 96 (9): 2646-2650. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04117.x.

Romagnuolo J, Bardou M, Rahme E, Joseph L, Reinhold C, Barkun AN: Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography: A meta-Analysis of Test Performance in Suspected Biliary Disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003, 139 (7): 547-557.

Misra SP, Dwivedi M: Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic sphincterotomy: diagnosis, management and prevention. National Medical Journal of India. 2002, 15 (1): 27-31.

Cotton PB, Jowell PS, Baillie J: Spectrum of complications after diagnostic ERCP and effects of comorbidities [abstract]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1994, 40: 18-

Baillie J: Predicting and preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2002, 4: 112-119.

Bravo Vergel Y, Chilcott J, Kaltenthaler E, Walters SJ, Blakeborough A, Thomas S: Economic evaluation of MR cholangiopancreatography compared to diagnostic ERCP for the investigation of biliary tree obstruction. International Journal of Surgery. 2006, 4 (1): 12-19. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.01.007.

Altman DG: Some common problems in medical research. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. 1991, London: Chapman & Hall, Chapter 14: 418-

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2342/6/9/prepub

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to Helen Bouchier for conducting the database searches.

Funding for this work was provided by the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the NCCHTA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EK carried out the systematic review and prepared the manuscript. SJW carried out the statistical analysis and contributed to the manuscript writing. JC and YBV helped to draft the manuscript. ST and AB provided clinical advice and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaltenthaler, E.C., Walters, S.J., Chilcott, J. et al. MRCP compared to diagnostic ERCP for diagnosis when biliary obstruction is suspected: a systematic review. BMC Med Imaging 6, 9 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2342-6-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2342-6-9