Abstract

Background

A high rate of post-infectious fatigue and abdominal symptoms two years after a waterborne outbreak of giardiasis in Bergen, Norway in 2004 has previously been reported. The aim of this report was to identify risk factors associated with such manifestations.

Methods

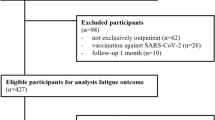

All laboratory confirmed cases of giardiasis (n = 1262) during the outbreak in Bergen in 2004 received a postal questionnaire two years after. Degree of post-infectious abdominal symptoms and fatigue, as well as previous abdominal problems, was recorded. In the statistical analyses number of treatment courses, treatment refractory infection, delayed education and sick leave were used as indices of protracted and severe Giardia infection. Age, gender, previous abdominal problems and symptoms during infection were also analysed as possible risk factors. Simple and multiple ordinal logistic regression models were used for the analyses.

Results

The response rate was 81% (1017/1262), 64% were women and median age was 31 years (range 3-93), compared to 61% women and 30 years (range 2-93) among all 1262 cases. Factors in multiple regression analysis significantly associated with abdominal symptoms two years after infection were: More than one treatment course, treatment refractory infection, delayed education, bloating and female gender. Abdominal problems prior to Giardia infection were not associated with post-infectious abdominal symptoms. More than one treatment course, delayed education, sick leave more than 2 weeks, and malaise at the time of infection, were significantly associated with fatigue in the multiple regression analysis, as were increasing age and previous abdominal problems.

Conclusion

Protracted and severe giardiasis seemed to be a risk factor for post-infectious fatigue and abdominal symptoms two years after clearing the Giardia infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The intestinal protozoan Giardia duodenalis is a common cause of waterborne outbreaks in western countries since the cysts are relatively resistant to water treatment, and in most developing countries the parasite is highly endemic [1, 2]. The clinical impact of Giardia infection ranges from mild self-limiting disease to life-threatening malnutrition [3–5].

Post-infectious complications have been described in children in developing countries, where giardiasis contributes to malnutrition and growth retardation with later risk for impaired cognitive function [6].

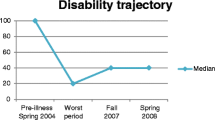

Also post-giardiasis complications in a western country have recently been described. We reported a high level of post-infectious fatigue (41%) and abdominal symptoms (38%) among 1017 cases two years after a waterborne outbreak in Bergen, Norway in 2004 [7, 8]. The aim of this study was to investigate risk factors associated with such manifestations.

Methods

Study site and participants

Inclusion criteria was laboratory verified Giardia infection from the Bergen outbreak. All Giardia-positive cases diagnosed by stool microscopy (formalin-ether concentration) and/or antigen-test (ImmunoCard STAT! Cryptosporidium/Giardia rapid assay; Meridian Bioscience) at the local parasitology laboratory in Bergen were registered in the period from October 2004 to June 2005, and an additional 16 cases considered to be related to the outbreak were registered until December 2005. The majority of cases was registered in November 2004 (n = 863). A higher number than normal was registered also in 2005 (n = 172) after the water supply in December 2004 was considered free from Giardia cysts, probably due to protracted or secondary infections. A few cases known not to be infected in Bergen were excluded. According to this, a study population of 1262 cases, later referred to as "all cases", was defined.

The investigating laboratory is the only parasitology laboratory in the region, and prior to the outbreak about 50 cases a year were diagnosed, mainly infected abroad [9].

Questionnaire

In August 2006, two years after the peak of the outbreak, a questionnaire was mailed to all cases, followed by an additional letter to non-respondents one month later.

We asked about abdominal problems prior to giardiasis; among these if abdominal problems had ever led to any of the following: Hospitalisation, sick leave, use of medication, seeing a doctor or problems without seeking health care, or if they did not have abdominal problems prior to September 2004.

Cases were asked about the following symptoms during giardiasis: Diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss, malaise, nausea, foul smell and bloating. They were also asked about sick leave (0, <1, 1, 1-2 or >2 weeks), delayed education (0, <1, 1 or > 1 semester), time before abdominal symptoms disappeared (< 1, 1-3, 4-6 or 7-18 months) and number of treatment courses before abdominal symptoms ceased (0, 1, 2, >2, or recovered during treatment but relapsed).

We also asked if they had present problems with abdominal symptoms and with fatigue. The results for these latter questions have been published previously [8]. Present symptoms including nausea, bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation and reduced appetite were recorded on a scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (severe symptoms). These questions have previously been used in recording severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [10].

Number of cases working/studying was estimated as cases answering the questions concerning sick leave/delayed education, minus cases answering that they were not working/studying.

Abdominal symptoms were reported as "no", "unsure" or "yes" on the question "Do you have abdominal symptoms now that you did not have prior to the Giardia infection?" Fatigue was reported as "less or same as usual", "more than usual" or "much more than usual" on the question "Do you have problems with fatigue?" These were used as ordinal response variables in the statistical analyses.

Characteristics evaluated as possible risk factors

Whether protracted and severe Giardia infection could be associated with post-infectious fatigue or abdominal symptoms was studied, and number of treatment courses, delayed education and sick leave were all used as indices of protracted and severe infection in the statistical analyses. A sub-cohort of treatment resistant cases with mean symptom duration seven months, who had all been successfully treated in our out patient clinic, was also included in the statistical analyses. The characteristics and results from treatment of this cohort has been published previously [11]. Age, gender, previous abdominal problems and symptoms during infection were also evaluated as possible risk factors.

Statistical methods

For each of the two ordinal response variables at two years follow-up, fatigue and abdominal symptoms, the possible risk factors were analysed as explanatory variables using ordinal logistic regression with the proportional odds model. In the proportional odds model the results are expressed as the ratio of the odds for a response above a certain level in the exposed to the odds for a response above this level in the unexposed. This odds ratio (OR) is modelled to be independent of the chosen level. First, for each of the response variables, simple ordinal logistic regression analysis was done for all risk factors. Then, all factors were included in a multiple ordinal logistic regression analysis (proportional odds model) [12]. From the analyses, unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios were estimated. To avoid loosing cases in the multiple regression analyses, missing values were included as valid categories in some variables as follows: "Not recovered" was included in the variable "Treatment courses", "Not working" in "Sick leave" and "Not a student" in "Delayed education". To evaluate the possible risk that these variables only reflect the response variables, the multiple regression analyses were performed with and without each of them. Age and gender were included into all models with no regards to significance. The final model included all variables with p < 0.05 (likelihood ratio test). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 or STATA.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained. The regional ethics committee and the Privacy Ombudsman for Research approved the data collection and analyses of the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The response rate was 81% (1017/1262), later referred to as "respondents". Median age among respondents was 31 years (range 3-93) and 64% were women, compared to 30 years (range 2-93) and 61% among all cases. Among the respondents, 722 (71%) were estimated to be working and 460 (45%) to be students. Prior to the Giardia outbreak, 12% of respondents (124/1017) had visited a doctor due to abdominal problems, 10% (98/1017) had had abdominal symptoms without seeking health care, 4% (42/1017) had used medication for such symptoms, 2% (19/1017) had been hospitalised and 2% (19/1017) had been on sick leave due to abdominal problems prior to the Giardia outbreak. A majority of 71% (718/1017) reported to have had no previous abdominal problems.

Abdominal symptoms and fatigue two years after infection was recorded from 38% (389/1017) and 41% (419/1017) respectively as previously reported [8] (Table 2). Bloating was the symptom reported to be most severe (Table 2).

Giardia infection

Symptoms during Giardia infection, as reported two years later are shown in Table 3. Less than four weeks duration of symptoms, irrespective of treatment, was recorded in 18%. Only 1% became well without medication. Sick leave was reported by 46%, and almost half of these had been on sick leave for more than two weeks. Delayed education was reported in 33%, and 17% had one or more semester delay.

Factors associated with fatigue and abdominal symptoms

The analyses of risk factors associated with abdominal symptoms and fatigue are presented in Table 4 and 5, respectively.

More than one course of treatment for giardiasis, as well as delayed education, was significantly associated with both fatigue and abdominal symptoms in all analyses. Previous abdominal problems were not significantly associated with post-infectious abdominal symptoms in any analyses.

Female gender turned out not to be significantly associated with abdominal symptoms when the variable "treatment courses" was left out from the multiple regression analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

We have previously reported a high prevalence of fatigue (41%, 419/1017) and abdominal symptoms (38%, 389/1017), and a highly significant association between these symptoms, two years after the Bergen outbreak [8]. In this study we report an association between protracted and severe Giardia infection and such symptoms.

Fatigue has been described following Q-fever, Epstein Barr virus infection, Ross River virus infection, brucellosis, Lyme disease, viral meningitis and Dengue fever, and in the first three of these, severe infection was a risk factor [13–16].

In a sub-cohort of referred cases after the Bergen outbreak, 81% (66/82) fulfilled the Rome II criteria for IBS [17]. Post-infectious (PI)-IBS has been reported with a median prevalence of around 10% following gastroenteritis of various aetiology; Campylobacter [18–20], Salmonella [21–23], Shigella [24–26], Escherichia coli [20] and Trichinella spiralis [27], and severe infection was the most important risk factor in these reports [24, 28–30].

A possible weakness in our definition of indices of protracted and severe Giardia infection is that sick leave or delayed education may be signs of PI-IBS or fatigue rather than protracted infection or inflammation. Particularly those reporting ">1 semester delayed education", but also "sick leave > 2 weeks", could potentially be cases actually reporting persistent symptoms, but excluding them from the statistical analyses would have created a selection bias. More than one treatment course is a reliable index of persistent infection and the finding of this as a highly significant risk factor in all analyses supports the hypothesis that protracted and severe infection may cause post-infectious complications. However, some patients may not have had stool samples tested between the courses, and may therefore have experienced post-infectious complaints rather than protracted infection. Results regarding the sub-cohort of referred treatment refractory cases must be interpreted with caution due to the very low sample size (n = 29) [11].

If our findings are causal, then the surprisingly high level of fatigue and abdominal symptoms reported, may have two possible explanations: A substantial number of cases had protracted infection due to delayed treatment explained by late detection of the outbreak [7], and/or the infection caused inflammation in a high number of cases, also after clearing the parasites [31]. Giardiasis may cause damage to the intestinal epithelial brush border, villous atrophy and inflammation [32]. In duodenal biopsies from a sub-cohort of 124 cases with symptoms for 8 months (mean) from the Bergen outbreak, inflammation was found in 47% [31], which is surprisingly high compared to a previous report of duodenal inflammation in 4% of 462 Giardia cases from Germany [33]. This supports that protracted Giardia infection, and possibly protracted intestinal inflammation, may have induced PI-IBS and fatigue in this cohort. Low-grade inflammation in gut-mucosa has been described as a possible mechanism for IBS also following other infections [34].

The high prevalence of inflammation in this outbreak may be explained by immunological host factors, but probably also by parasite virulence factors. Studies addressing the possible association between Giardia genotypes and clinical manifestations have shown different results: Both genotype A and B have been responsible for severe symptoms, with the genotype less prevalent in the community responsible for more severe clinical manifestation [35–38]. In Norway 11% of raw water samples contains Giardia parasites in low concentrations, most commonly genotype A, while the outbreak strain in Bergen was assemblage B [39, 40]. Previous studies from the outbreak suggest that some sub-genotypes induced a more severe infection [11, 41], and one may speculate if particular sub-genotypes lead to an immune reaction responsible for protracted low-grade inflammation. Also in IBS following infections other than giardiasis, toxicity within species has been reported as a risk factor, as in Campylobacter infection [18].

Age was significantly associated with fatigue as previously reported from this cohort [8], which is in line with findings in a Norwegian population study [42]. We did not find any significant association between age and abdominal symptoms. Age >60 years was protective against PI-IBS in one study [29], and one mechanism was suggested to be that the gut in older subjects might be less reactive to infection [43].

Female gender seemed to be a risk factor for both fatigue and abdominal symptoms in some but not all analyses, and this finding must therefore be interpreted with caution. An association between chronic fatigue and female gender has been reported in other studies [13, 42, 44–46]. Female gender has also been associated with PI-IBS in some reports; however, this association was no longer significant when analyses were adjusted for psychological disturbances [19, 28, 29, 47].

Malaise during infection was associated with fatigue, and bloating with abdominal symptoms. This may either indicate recall bias influenced by symptoms present at the time of reporting, or a real risk of complications if these symptoms are prominent.

There was no association between previous abdominal problems and post-infectious abdominal symptoms. The finding that "previous abdominal problems without seeking health care" was associated with fatigue should be interpreted with caution since other factors measuring previous abdominal problems were not associated. The possible impact of recall bias on the outcome regarding previous abdominal problems in this study may be less since the questions were phrased as facts ("hospitalised" etc) rather than symptoms.

Chronic Giardia infection may develop in 15% of patients if not treated [4], and may be misdiagnosed as IBS due to similar symptoms [48]. Giardia was found in 6.5% of IBS cases in one study from Italy [49], and in a meta-analysis from the Nordic countries, giardiasis was found in 3.0% of the asymptomatic, and in 5.8% of the symptomatic, population [50].

We have previously shown that all referred treatment refractory cases after the Bergen outbreak eradicated the parasite, evaluated by seven negative stool samples up to four weeks after treatment [11]. In 25 Giardia negative patients from this outbreak, treatment with metronidazole/albendazole or tetracycline/folic acid was not effective, and cryptic giardiasis was therefore excluded [51]. We have also described that IBS persisted in patients after normalisation of duodenal biopsies [17]. These reports support that chronic infection is not the cause of fatigue and abdominal symptoms in this cohort.

A major strength of the study is the large number of cases, and the high response rate. A limitation may be the risk of over-reporting of symptoms since local authorities have accepted to compensate any economical loss due to the infection. Possible reporting bias due to limitations in the questionnaire could have been reduced if validated measures of chronic fatigue and IBS had been used in a controlled study. Also, the study lacks information on co-morbidity and professional background. It is unclear whether these limitations have influenced the outcome of the study. On the other hand, the study was initiated by clinicians after observing a substantial number of patients with severe chronic fatigue and/or abdominal symptoms after giardiasis, supporting that self reporting of symptoms associated with giardiasis in this cohort is consistent with clinical observations.

Conclusions

Protracted and severe Giardia infection, or possibly inflammation, seems to be a risk factor for post-infectious fatigue and abdominal symptoms two years after clearing the parasites. These symptoms are often pronounced, reduce quality of life and have economical implications in the society. If the observed association is causal, shortening the duration of Giardia infection by early diagnosis and treatment may be important also in order to reduce the risk for such complications.

References

Savioli L, Smith H, Thompson A: Giardia and Cryptosporidium join the 'Neglected Diseases Initiative'. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22 (5): 203-208. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.015.

Gilman RH, Marquis GS, Miranda E, Vestegui M, Martinez H: Rapid reinfection by Giardia lamblia after treatment in a hyperendemic Third World community. Lancet. 1988, 1 (8581): 343-345. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91131-2.

Hill DRNT: Intestinal Flagellate and Ciliate Infections. 2006, Elsevier, 2: Second

Rendtorff RC: The experimental transmission of human intestinal protozoan parasites. II. Giardia lamblia cysts given in capsules. Am J Hyg. 1954, 59 (2): 209-220.

Farthing MJ: Giardiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996, 25 (3): 493-515. 10.1016/S0889-8553(05)70260-0.

Berkman DS, Lescano AG, Gilman RH, Lopez SL, Black MM: Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet. 2002, 359 (9306): 564-571. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07744-9.

Nygard K, Schimmer B, Sobstad O, Walde A, Tveit I, Langeland N, Hausken T, Aavitsland P: A large community outbreak of waterborne giardiasis-delayed detection in a non-endemic urban area. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 141-10.1186/1471-2458-6-141.

Morch K, Hanevik K, Rortveit G, Wensaas KA, Langeland N: High rate of fatigue and abdominal symptoms 2 years after an outbreak of giardiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 103 (5): 530-532. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.01.010.

Robertson LJ, Forberg T, Hermansen L, Gjerde BK, Langeland N: Demographics of Giardia infections in Bergen, Norway, subsequent to a waterborne outbreak. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008, 40 (2): 189-192. 10.1080/00365540701558672.

Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, Rufo PA, Zholudev A, Boone J, Lyerly D, Camilleri M, Hanauer SB: Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003, 98 (6): 1309-1314. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07458.x.

Morch K, Hanevik K, Robertson LJ, Strand EA, Langeland N: Treatment-ladder and genetic characterisation of parasites in refractory giardiasis after an outbreak in Norway. J Infect. 2008

Kleinbaum DG, Klein M: Logistic Regression. 2005, Springer, 2

Seet RC, Quek AM, Lim EC: Post-infectious fatigue syndrome in dengue infection. J Clin Virol. 2007, 38 (1): 1-6. 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.10.011.

Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, Vollmer-Conna U, Cameron B, Vernon SD, Reeves WC, Lloyd A: Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2006, 333 (7568): 575-10.1136/bmj.38933.585764.AE.

White PD, Grover SA, Kangro HO, Thomas JM, Amess J, Clare AW: The validity and reliability of the fatigue syndrome that follows glandular fever. Psychol Med. 1995, 25 (5): 917-924. 10.1017/S0033291700037405.

Harley D, Bossingham D, Purdie DM, Pandeya N, Sleigh AC: Ross River virus disease in tropical Queensland: evolution of rheumatic manifestations in an inception cohort followed for six months. Med J Aust. 2002, 177 (7): 352-355.

Hanevik K, Dizdar V, Langeland N, Hausken T: Development of functional gastrointestinal disorders after Giardia lamblia infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9: 27-10.1186/1471-230X-9-27.

Thornley JP, Jenkins D, Neal K, Wright T, Brough J, Spiller RC: Relationship of Campylobacter toxigenicity in vitro to the development of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2001, 184 (5): 606-609. 10.1086/322845.

Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC: Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003, 125 (6): 1651-1659. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.028.

Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF, Salvadori M, Collins SM: Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology. 2006, 131 (2): 445-450. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.053.

McKendrick MW, Read NW: Irritable bowel syndrome--post salmonella infection. J Infect. 1994, 29 (1): 1-3. 10.1016/S0163-4453(94)94871-2.

McKendrick MW: Post Salmonella irritable bowel syndrome--5 year review. J Infect. 1996, 32 (2): 170-171. 10.1016/S0163-4453(96)91715-6.

Mearin F, Perez-Oliveras M, Perello A, Vinyet J, Ibanez A, Coderch J, Perona M: Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: one-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005, 129 (1): 98-104. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.012.

Wang LH, Fang XC, Pan GZ: Bacillary dysentery as a causative factor of irritable bowel syndrome and its pathogenesis. Gut. 2004, 53 (8): 1096-1101. 10.1136/gut.2003.021154.

Ji S, Park H, Lee D, Song YK, Choi JP, Lee SI: Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Shigella infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005, 20 (3): 381-386. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03574.x.

Kim HS, Kim MS, Ji SW, Park H: [The development of irritable bowel syndrome after Shigella infection: 3 year follow-up study]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006, 47 (4): 300-305.

Soyturk M, Akpinar H, Gurler O, Pozio E, Sari I, Akar S, Akarsu M, Birlik M, Onen F, Akkoc N: Irritable bowel syndrome in persons who acquired trichinellosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007, 102 (5): 1064-1069. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01084.x.

Spiller RC: Role of infection in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007, 42 (Suppl 17): 41-47. 10.1007/s00535-006-1925-8.

Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R: Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. Bmj. 1997, 314 (7083): 779-782.

Halvorson HA, Schlett CD, Riddle MS: Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome--a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006, 101 (8): 1894-1899. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00654.x. quiz 1942

Hanevik K, Hausken T, Morken MH, Strand EA, Morch K, Coll P, Helgeland L, Langeland N: Persisting symptoms and duodenal inflammation related to Giardia duodenalis infection. J Infect. 2007

Muller N, von Allmen N: Recent insights into the mucosal reactions associated with Giardia lamblia infections. Int J Parasitol. 2005, 35 (13): 1339-1347. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.008.

Oberhuber G, Kastner N, Stolte M: Giardiasis: a histologic analysis of 567 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997, 32 (1): 48-51. 10.3109/00365529709025062.

Spiller R, Campbell E: Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006, 22 (1): 13-17. 10.1097/01.mog.0000194792.36466.5c.

Homan WL, Mank TG: Human giardiasis: genotype linked differences in clinical symptomatology. Int J Parasitol. 2001, 31 (8): 822-826. 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00183-7.

Sahagun J, Clavel A, Goni P, Seral C, Llorente MT, Castillo FJ, Capilla S, Arias A, Gomez-Lus R: Correlation between the presence of symptoms and the Giardia duodenalis genotype. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008, 27 (1): 81-83. 10.1007/s10096-007-0404-3.

Gelanew T, Lalle M, Hailu A, Pozio E, Caccio SM: Molecular characterization of human isolates of Giardia duodenalis from Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2007, 102 (2): 92-99. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.04.003.

Read C, Walters J, Robertson ID, Thompson RC: Correlation between genotype of Giardia duodenalis and diarrhoea. Int J Parasitol. 2002, 32 (2): 229-231. 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00340-X.

Robertson LJ, Hermansen L, Gjerde BK, Strand E, Alvsvag JO, Langeland N: Application of genotyping during an extensive outbreak of waterborne giardiasis in Bergen, Norway, during autumn and winter 2004. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72 (3): 2212-2217. 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2212-2217.2006.

Robertson LJ, Gjerde B: Occurrence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in raw waters in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2001, 29 (3): 200-207. 10.1177/14034948010290030901.

Robertson LJ, Forberg T, Hermansen L, Gjerde BK, Langeland N: Molecular characterisation of Giardia isolates from clinical infections following a waterborne outbreak. J Infect. 2007, 55 (1): 79-88. 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.02.001.

Loge JH, Ekeberg O, Kaasa S: Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: normative data and associations. J Psychosom Res. 1998, 45 (1 Spec No): 53-65. 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00291-2.

Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC: Age-related decline in rectal mucosal lymphocytes and mast cells. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004, 16 (10): 1011-1015. 10.1097/00042737-200410000-00010.

Reyes M, Nisenbaum R, Hoaglin DC, Unger ER, Emmons C, Randall B, Stewart JA, Abbey S, Jones JF, Gantz N, et al: Prevalence and incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Wichita, Kansas. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163 (13): 1530-1536. 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1530.

Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, Jordan KM, Plioplys AV, Taylor RR, McCready W, Huang CF, Plioplys S: A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1999, 159 (18): 2129-2137. 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2129.

Prins JB, Meer van der JW, Bleijenberg G: Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 2006, 367 (9507): 346-355. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68073-2.

Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Walters SJ, Underwood JE, Read NW: The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999, 44 (3): 400-406.

Stark D, van Hal S, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J: Irritable bowel syndrome: a review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis. Int J Parasitol. 2007, 37 (1): 11-20. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.009.

Grazioli B, Matera G, Laratta C, Schipani G, Guarnieri G, Spiniello E, Imeneo M, Amorosi A, Foca A, Luzza F: Giardia lamblia infection in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006, 12 (12): 1941-1944.

Horman A, Korpela H, Sutinen J, Wedel H, Hanninen ML: Meta-analysis in assessment of the prevalence and annual incidence of Giardia spp. and Cryptosporidium spp. infections in humans in the Nordic countries. Int J Parasitol. 2004, 34 (12): 1337-1346. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.08.009.

Hanevik K, Morch K, Eide GE, Langeland N, Hausken T: Effects of albendazole/metronidazole or tetracycline/folate treatments on persisting symptoms after Giardia infection: a randomized open clinical trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008, 40 (6-7): 517-522. 10.1080/00365540701827481.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/9/206/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Grete Thormodsæter (Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital) for technical help in collecting data, and Bjørn Blomberg (Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital) for technical assistance in creating the databases.

No external funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KM, KH, GR, KAW, TH and NL participated in the design of the study. KM collected data and drafted the manuscript. GEE and KM performed the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mørch, K., Hanevik, K., Rortveit, G. et al. Severity of Giardiainfection associated with post-infectious fatigue and abdominal symptoms two years after. BMC Infect Dis 9, 206 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-206

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-9-206