Abstract

Background

Both religious practices and male circumcision (MC) have been associated with HIV and other sexually-transmitted infectious diseases. Most studies have been limited in size and have not adequately controlled for religion, so these relationships remain unclear.

Methods

We evaluated relationships between MC prevalence, Muslim and Christian religion, and 7 infectious diseases using country-specific data among 118 developing countries. We used multivariate linear regression to describe associations between MC and cervical cancer incidence, and between MC and HIV prevalence among countries with primarily sexual HIV transmission.

Results

Fifty-three, 14, and 51 developing countries had a high (>80%), intermediate (20–80%), and low (<20%) MC prevalence, respectively. In univariate analyses, MC was associated with lower HIV prevalence and lower cervical cancer incidence, but not with HSV-2, syphilis, nor, as expected, with Hepatitis C, tuberculosis, or malaria. In multivariate analysis after stratifying the countries by religious groups, each categorical increase of MC prevalence was associated with a 3.65/100,000 women (95% CI 0.54-6.76, p = 0.02) decrease in annual cervical cancer incidence, and a 1.84-fold (95% CI 1.36-2.48, p < 0.001) decrease in the adult HIV prevalence among sub-Saharan African countries. In separate multivariate analyses among non-sub-Saharan African countries controlling for religion, higher MC prevalence was associated with a 8.94-fold (95% CI 4.30-18.60) decrease in the adult HIV prevalence among countries with primarily heterosexual HIV transmission, but not, as expected, among countries with primarily homosexual or injection drug use HIV transmission (p = 0.35).

Conclusion

Male circumcision was significantly associated with lower cervical cancer incidence and lower HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa, independent of Muslim and Christian religion. As predicted, male circumcision was also strongly associated with lower HIV prevalence among countries with primarily heterosexual HIV transmission, but not among countries with primarily homosexual or injection drug use HIV transmission. These findings strengthen the reported biological link between MC and some sexually transmitted infectious diseases, including HIV and cervical cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Geographical variations in HIV prevalence have been observed between less-developed and more-developed countries, as well as within regions of similar socioeconomic development [1–5]. The epidemiology of HIV and other infectious diseases have been associated with both religious practices and male circumcision [1–19]. Religious beliefs and practices dictate many societal and sexual behaviors that influence transmission of sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) [20]. Male circumcision has been more common among populations with lower rates of HIV, cervical cancer, and other STIs [3, 10–13], and shown in one randomized trial to reduce HIV transmission [21]. Although religious affiliation is a major determinant of male circumcision status [12], many analyses have not controlled for religion when examining relationships between male circumcision and infectious diseases.

This study builds upon and further expands our previously reported analyses of variables associated with country-specific HIV prevalence and cervical cancer incidence [5, 22]. In our extensive analysis of HIV co-factors, among 81 variables male circumcision had the strongest association with HIV prevalence [5]. We now present a more thorough examination of the association between male circumcision and HIV prevalence by better adjusting for religion, by separately analyzing the sub-Saharan African region, and by conducting separate analyses between countries with sexual versus non-sexual primary modes of HIV transmission. Our previous ecological analysis of cervical cancer utilized 54 country-level variables, but did not include the important determinant of male circumcision [13, 22]. We complete our previous analysis by describing the relationships between male circumcision and cervical cancer, and by including male circumcision in the previously reported multivariate model. In addition, we further expand on our previous studies by describing the epidemiology of male circumcision among developing countries and by describing associations between male circumcision and five other infectious diseases.

Methods

We conducted an ecological study of country-level variables among developing countries. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 'Human Development Report 2004' provided the Human Development Index, which determines each country's development status on the basis of life expectancy, educational attainment, and adjusted real income [23]. Countries classified as high human development ("developed") countries were excluded from the analyses under the assumption that they have greater capacity to sustain national treatment and prevention programs, and have different epidemiological infectious disease profiles. Therefore, subsequent country-specific data were collected for 122 low and medium human development ("developing") countries.

Data collection

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) provided country-specific age-standardized HIV seroprevalence per 100 adults 15–49 years old for the year 2004 for 100 countries [24]. Countries with <0.1% of adults infected with HIV were considered to have an adult seroprevalence of 0.05%. The International Agency for Research on Cancer provided country-specific annual age-standardized cervical cancer incidence [a surrogate measure for Human Papillomavirus (HPV)] per 100,000 females for the year 2000 for 117 countries and the most recent country-specific Herpes Simplex Virus type-2 (HSV-2) seroprevalence per 100 women for 23 countries [25, 26]. The World Health Organization provided the most recent country-specific syphilis seroprevalence per 10,000 women for 43 countries [27], and Hepatitis C prevalence per 100 adults for 75 countries [28]. The UNDP provided country-specific prevalence of all forms of tuberculosis per 100,000 people for the year 2002 for 110 countries and malaria prevalence per 10,000 people for the year 2000 for 94 countries [23]. We did not include chlamydia or gonorrhea in this analysis due to a lack of available data.

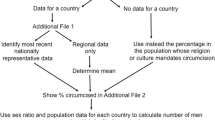

We used survey data from various published sources [3, 11–13, 15, 29, 30], including Demographic and Health Surveys and Behavioral Surveillance Surveys [31–35] to categorize the country-wide prevalence of male circumcision as "low" (<20%), "intermediate" (20–80%), or "high" (>80%), as we have previously done [5, 10]. These categories were chosen to best minimize misclassification. When published country-specific data were not available, we used ethnographic confidence methods, as previously utilized by Halperin and Bailey [5, 10], to categorize country-specific male circumcision prevalence as low, intermediate, or high. The classification of country-specific male circumcision prevalence was independently verified by three colleagues (listed in Acknowledgements). We omitted four developing countries (Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Vanuatu) from all analyses because their male circumcision prevalence could not be confidently categorized.

The United Nations Population Division provided all population statistics estimated for the year 2000 [36]. UNAIDS provided data for geographical regions [24]. We used the first listed mode of transmission from the UNAIDS 'HIV/AIDS Epidemic Update 2002' as the primary mode of HIV transmission for each geographical region [37]. The United States Central Intelligence Agency 'The World Factbook' provided both the percentage of Muslims and the percentage of Christians within each country [38].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted on 118 developing countries using Stata Version 8.0 [39]. All regression statistics were performed using a robust variance to account for unmeasured ecologic and population differences. We conducted separate analyses of HIV prevalence among sub-Saharan African and non-sub-Saharan African countries due to the differing severity and nature of the epidemics [40–42]. We also conducted separate analyses among non-sub-Saharan African regions whose primary mode of HIV transmission was heterosexual contact versus homosexual contact or injection drug use [24]. Heterosexual contact was the primary mode of HIV transmission for the sub-Saharan African region. HIV seroprevalence was natural log (ln)-transformed to create a more normal distribution for regression analyses. Countries were categorized into tertiles as having low (<5%), intermediate (5–55%), and high (>55%) percentage of predominantly Muslims, and as having low (<6%), intermediate (6–55%), and high (>55%) percentage of predominantly Christians.

The mean and standard deviation for each infectious disease were separately summarized among countries with low and high male circumcision prevalence. Means and standard deviations for cervical cancer incidence and HIV prevalence were also separately summarized among countries with low and high male circumcision prevalence within each religious tertile group. Means and standard deviations were analyzed for statistical significance between high versus low male circumcision groups using 2-sample t tests for independent samples with unequal variances.

Univariate linear regression statistics examined category of male circumcision prevalence with each infectious disease. Results are presented by order of the R 2 value, which estimates the amount of the variance explained by the association. Since only HIV prevalence and cervical cancer incidence were significantly associated with male circumcision in univariate analyses, subsequent multivariate analyses were only performed for these two outcomes. Multivariate analyses of covariance models included each country's percentage of the population Muslim and percentage of the population Christian.

Additional multivariate analyses were conducted for cervical cancer incidence and HIV prevalence based on our previously published models [5, 22]. In brief, a multivariate model of cervical cancer incidence was conducted adjusting for the 6 additional variables that were previously found to be significant (p < 0.05) indicators of cervical cancer incidence. Definitions and sources of these variables (number of doctors per 100,000 people, percent of children immunized for measles, female disability-adjusted life expectancy in years, percent of female adult illiteracy rate, percent of infants with low birth weight, and geographic region as defined by the International Agency for Research on Cancer), have been previously described [22]. Similarly, a multivariate model of HIV prevalence was conducted adjusting for the 6 additional variables that were previously found to be significant (p < 0.05) indicators of HIV prevalence. Detailed methods, including definitions and sources of these variables (years since HIV was first reported, geographic region, percent of the population younger than 25 years, percent of female adult illiteracy rate, percent of children fully immunized for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis, and number of doctors per 100,000 people), have been previously described [5].

Results

Male circumcision prevalence

The classification of male circumcision prevalence is listed in Table 1 for 118 developing countries. Among these, 53 countries, containing 700 million males, were categorized as having a high (>80%) male circumcision prevalence, 14 countries, containing 135 million males, were categorized as having an intermediate (20–80%) male circumcision prevalence, and 51 countries, containing 1.6 billion males, were categorized as having a low (<20%) male circumcision prevalence.

Male circumcision prevalence had a distinct geographical pattern. Thirteen of 14 (93%) developing countries in North Africa and the Middle East had a high male circumcision prevalence. Twenty-eight of 45 (62%) sub-Saharan African countries had a high male circumcision prevalence. Eight of 27 (30%) Southeast Asian and Pacific Island countries had a high male circumcision prevalence, and most circumcised males resided in Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, or the Philippines. Only 4 of 18 (22%) developing countries in Europe and Central Asia had a high male circumcision prevalence, and all 18 developing countries in Latin American and the Caribbean region had a low male circumcision prevalence.

Male circumcision and religion

As expected, male circumcision was strongly associated with religious variables (data not presented). A greater percent of the population being Muslim was strongly associated with more male circumcision prevalence (p < 0.001). Conversely, a greater percent of the population being Christian was strongly associated with less male circumcision (p < 0.001). Among 49 countries with high male circumcision prevalence, the mean percentage of the population Muslim was 69% and the mean percentage of the population Christian was 16%.

Male circumcision and infectious diseases

In univariate regression analyses, male circumcision was associated with HIV prevalence among sub-Saharan African countries, HIV prevalence among non-sub-Saharan African countries with primarily heterosexual contact, HIV prevalence among non-sub-Saharan countries with primarily homosexual contact or injection drug use, and cervical cancer incidence (Table 2). Male circumcision was not associated with HSV-2, syphilis, nor, as expected, with the non-sexually-transmitted-disease prevalences of Hepatitis C, tuberculosis, or malaria. Among sub-Saharan African countries, HIV prevalence was 3.0% among countries with a high male circumcision prevalence and 16.5% among countries with a low male circumcision prevalence (p < 0.001). Among non-sub-Saharan African countries with primarily heterosexual HIV transmission, HIV prevalence was 0.09% among countries with a high male circumcision prevalence and 0.76% among countries with a low male circumcision prevalence (p < 0.001). Similarly, the mean annual cervical cancer incidence was 20.5/100,000 women among countries with a high male circumcision prevalence and 35.0/100,000 women among countries with a low male circumcision prevalence (p < 0.001). Although there was no significant association between male circumcision and HSV-2 prevalence, the size and direction of the coefficient suggests that male circumcision could be associated with reduced HSV-2 prevalence given a larger sample size.

Religion and infectious diseases

In univariate regression analyses, religion was also strongly associated with HIV and cervical cancer. Each percent increase of the population Muslim was associated with a 0.21/100,000 women (CI 0.15-0.28, p < 0.001) decrease in cervical cancer incidence, and a 1.25-fold (CI 1.16-1.35, p < 0.001) and 1.19-fold (CI 1.12-1.27, p < 0.001) decrease in adult HIV prevalence among sub-Saharan African and non-sub-Saharan African countries, respectively. Similarly, each percent increase of the population Christian was associated with a 0.26/100,000 women (CI 0.19-0.34, p < 0.001) increase in cervical cancer incidence, and a 1.32-fold (CI 1.20-1.45, p < 0.001) and 1.20-fold (CI 1.12-1.30, p < 0.001) increase in adult HIV prevalence among sub-Saharan African and non-sub-Saharan African countries, respectively.

Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases

Mean rates of cervical cancer incidence and HIV prevalence are presented among countries with low and high male circumcision prevalence in Figures 1, 2, 3, after separately stratifying countries into tertiles for percent Muslim and percent Christian. In nearly all religious tertile groups, mean cervical cancer incidence or HIV prevalence was lower among countries with a high male circumcision prevalence. Mean differences between high and low male circumcision groups were statistically significant for 7 of 14 (50%) tertile groups, and 2 additional tertile groups (14%) showed a borderline significance. When excluding each of the major religions in separate multivariate analyses, there were no meaningful changes in the associations between infectious diseases and male circumcision prevalence.

In a multivariate model, percent of the population Christian and male circumcision, but not percent of the population Muslim, remained independently associated with cervical cancer incidence (Table 3). After stratifying the countries by religious groups, each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was associated with a 3.65/100,000 women (CI 0.54-6.76, p = 0.02) decrease in annual cervical cancer incidence. These 3 measures (prevalence of male circumcision, percent Muslim, and percent Christian) accounted for 40% of the variance in cervical cancer incidence among the 105 developing countries included in the model. In a multivariate model adjusted for 6 additional country-specific variables previously found to be associated with cervical cancer incidence [22], each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was highly associated with a 10.38/100,000 women (CI 4.94-15.82, p < 0.001) decrease in annual cervical cancer incidence. The 9 variables accounted for 59% of the variance in cervical cancer incidence among the 85 countries included in the model. Furthermore, male circumcision had a stronger association with cervical cancer incidence than all the other variables included in the model.

Among sub-Saharan African countries, percent of the population Muslim and male circumcision, but not percent of the population Christian, remained independently associated with HIV prevalence (Table 4). After stratifying the countries by religious groups, each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was associated with a 1.84-fold (CI 1.36-2.48, p < 0.001) decrease in adult HIV prevalence. In a multivariate model adjusted for 6 additional country-specific variables previously found to be associated with HIV prevalence [5], each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was associated with a 2.27-fold (CI 1.51-3.42, p = 0.001) decrease in adult HIV prevalence.

Among all non-sub-Saharan African countries, male circumcision remained independently associated with HIV prevalence among countries in regions with heterosexual contact as the primary mode of HIV transmission, but not among countries in regions with either homosexual contact or injection drug use as the primary mode of HIV transmission (Table 4). When stratifying the countries by religious groups among countries with primarily heterosexual HIV transmission, each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was associated with a 8.94-fold (95% CI 4.30-18.60) decrease in adult HIV prevalence. In a multivariate model adjusted for 6 additional country-specific variables [5], each categorical increase of male circumcision prevalence was associated with a 4.94-fold (95% CI 2.29-10.65, p = 0.001) decrease in adult HIV prevalence. In a separate multivariate model, after stratifying the countries by religious groups among countries with primarily homosexual contact or injection drug use HIV transmission, male circumcision was not significantly associated with HIV prevalence (p = 0.35). When adjusting the multivariate model for the 6 additional country-specific variables [5], male circumcision prevalence was not significantly associated with HIV prevalence (p = 0.70).

Discussion

This ecological study of 118 developing countries expands results from our previous analyses [5, 22] by elucidating patterns and associations between male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases, particularly HIV. Male circumcision, which is routinely practiced in the Middle East, northern and western Africa, and western Asia, was associated with lower rates of certain STIs, HIV and cervical cancer (a proxy for HPV), but not with infections transmitted by non-sexual routes. In general, more male circumcision was strongly associated with lower cervical cancer rates and fewer HIV cases, independent of religion. Furthermore, male circumcision was independently associated with HIV among countries with primarily heterosexual HIV transmission, and not among countries with primarily homosexual or injection drug use HIV transmission. These findings all suggest that male circumcision is a true protective factor that reduces the sexual transmission of HIV and possibly HPV, independent of Muslim and Christian religions.

An ecologic study of this type has limitations, as we have previously acknowledged [5, 22]. In brief, ecological analyses cannot measure correlates of risk at the individual-level. Second, the temporal sequence of events in individuals is undetermined. Since the approximate age at circumcision varies by country, the results could be affected if a significant proportion delayed male circumcision until after initiation of sexual activity. Third, the validity of country-level data undoubtedly varies, and some data, such as HSV-2 prevalence, were not available for many countries. Although mean HSV-2 prevalence was lower among countries with more male circumcision, the limited number of countries with HSV-2 data (23 countries) gave relatively low power for examining the significance of this association. Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, statistics on the distribution and variation within countries were not complete. Some countries, such as Kenya, have widely varying regional prevalences of male circumcision and HIV [32]. For example, western Kenya, where less than 20% of males are circumcised, has a much higher HIV prevalence than regions of the country where nearly all men are circumcised [3, 32]. The 2003 Kenya survey also found uncircumcised males had over three-fold higher HIV prevalence as compared to circumcised males, and HIV prevalence in circumcised men was nearly identical among the major religious groups (2.6% among Catholics, 3.0% in Protestant/other Christians, and 2.9% in Muslims) [32]. Finally, not all population-level measures that may impact infectious disease transmission, such as patterns of risk behaviors, condom availability and utilization, and injection drug use, were included in this analysis. Despite these limitations, findings from this ecological analysis support a biological relationship between male circumcision and certain STIs.

Previous studies, including a recent Cochrane review [16], have also found male circumcision to be associated with a reduced risk of HPV detection in men [14], cervical cancer in female partners [13], and HIV infection [3, 11, 12, 15, 17], while associations between male circumcision and HSV-2 and gonorrhea are less clear [15, 19, 43]. However, these studies were generally conducted among geographically-limited populations and many were unable to adequately control for religion. By comparison, our study described the global distribution of male circumcision prevalence, examined a large number of geographically-diverse countries and several infectious diseases, separately analyzed countries by primarily heterosexual and non-heterosexual transmission of HIV, and included relatively complete and recent surveillance data. Our study supports results of other studies by demonstrating independent associations of male circumcision with reduced cervical cancer rates and HIV cases, after stratifying the countries for Muslim and Christian religions, among a large sample of developing countries.

Others have described biologically plausible mechanisms by which male circumcision may reduce the transmission of certain STIs [18, 19, 44, 45]. First, circumcised males may have less difficulty maintaining penile hygiene, which may reduce the acquisition of STIs by decreasing inflammation and the carriage time of pathogens in the foreskin [19, 45]. Secondly, the non-keratinized epidermis of the prepuce in uncircumcised males may provide an easier portal of entry to STIs [19, 44, 45]. Third, the inner mucosal surface of the prepuce, which has a high density of HIV target cells (CD4+ T-cells, Langerhans cells, macrophages), has been shown to become more easily infected with HIV as compared to outer foreskin tissue [45]. Given these biological differences, it is entirely plausible that uncircumcised males are at a greater risk of acquiring some STIs, and of transmitting them to their sexual partners [12].

According to UNAIDS, heterosexual transmission was the primary mode of HIV transmission in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and South and South-East Asia, and homosexual transmission was the primary mode of HIV transmission in Latin America [37]. In our analysis, male circumcision was strongly associated with HIV among developing countries with heterosexual contact as the primary mode of HIV transmission, and not among developing countries whose primary mode of HIV transmission was not heterosexual contact (Eastern Europe, Central and Eastern Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific). These results further support the biological role of male circumcision as a protective factor in HIV transmission. Furthermore, the fact that HIV prevalence in many predominantly Christian countries that practice male circumcision, such as the Philippines, Benin, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, is similarly low as in predominantly Muslim countries in the same regions, suggests that the biological effect of male circumcision may be at least as important as religion in determining HIV prevalence [24].

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that male circumcision was strongly associated with lower cervical cancer rates and fewer HIV cases among countries with heterosexual contact as the primary mode of HIV transmission, independent of religion. One randomized controlled trial has demonstrated that male circumcision is highly protective of HIV acquisition [21]. Therefore, while HIV and cervical cancer are impacted by a complex set of biological, social, and public health influences, male circumcision appears to play a prominent role in decreasing transmission of certain STIs. Although male circumcision must not substitute for other HIV and STI prevention strategies [46], the international public health and medical community should consider the implications and practicalities of integrating safe, voluntary male circumcision services with existing HIV prevention programs, particularly in countries with low prevalence of male circumcision and high prevalence of sexually-transmitted HIV.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV-2:

-

herpes simplex virus type-2

- STIs:

-

sexually-transmitted infections

- UNDP:

-

United Nations Development Programme

- UNAIDS:

-

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- HPV:

-

human papillomavirus

References

Caldwell JC, Caldwell P: The African AIDS epidemic. Sci Am. 1996, 274: 62-3.

Carael M, Buvé A, Awusabo-Asare K: The making of HIV epidemics: What are the driving forces?. AIDS. 1997, 2 (Suppl): 185-205.

Auvert B, Buvé A, Ferry B, Carael M, Morison L, Lagarde E, Robinson NJ, Kahindo M, Chege J, Rutenberg N, Musonda R, Laourou M, Akam E, Study Group on the Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities: Ecological and individual level analysis of risk factors for HIV infection in four urban populations in sub-Saharan Africa with different levels of HIV infection. AIDS. 2001, 15 (Suppl 4): S15-S30. 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00003.

Auvert B, Ferry B: Modeling the spread of HIV infection in four cities of sub-Saharan Africa [abstract]. Presented at XIV International AIDS Conference, 2002; Barcelona

Drain PK, Smith JS, Hughes JP, Halperin DT, Holmes KK: Correlates of national HIV seroprevalence. An ecological analysis of 122 developing countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004, 35: 407-420.

Bongaarts J, Reining P, Way P, Conant F: The relationship between male circumcision and HIV infection in African populations. AIDS. 1989, 3: 373-377. 10.1097/00002030-198906000-00006.

Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, Gakinya MN, Cheang M, Ndinya-Achola JO, Piot P, Brunham RC: Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989, 2: 403-407. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90589-8.

Moses S, Bradley J, Nagelkerke N, Ronald AR, Ndinya-Achola JP, Plummer FA: Geographical patterns of male circumcision practices in Africa: association with HIV prevalence. Int J Epidem. 1990, 19: 693-697.

Gray PB: HIV and Islam: is HIV prevalence lower among Muslims?. Soc Sci & Med. 2004, 58: 1751-1756. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00367-8.

Halperin DT, Bailey RC: Male circumcision and HIV infection: 10 years and counting. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1813-1815. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03421-2.

Lavreys L, Rakwar JP, Thompson ML, Jackson DJ, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, Bwayo JJ, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK: Effect of circumcision on incidence of HIV and other STDs: a prospective cohort study of truck company employees in Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1999, 180: 330-336. 10.1086/314884.

Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Mangen FW, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Kelly R, Meehan M, Chen MZ, Li C, Wawer MJ, for the Rakai Project Team: Male circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2000, 14: 2371-2381. 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019.

Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV, de Sanjose S, Eluf-Neto J, Ngelangel CA, Chichareon S, Smith JS, Herrero R, Moreno V, Franceschi S, International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group: Male circumcision, penile Human Papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 1105-1112. 10.1056/NEJMoa011688.

Baldwin SB, Wallace DR, Papenfuss MR, Abrahamsen M, Vaught LC, Giuliano AR: Condom use and other factors affecting penile Human Papillomavirus detection in men attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Trans Dis. 2004, 31: 601-607. 10.1097/01.olq.0000140012.02703.10.

Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, Gangakhedkar RR, Brookmeyer RS, Divekar AD, Mehendale SM, Bollinger RC: Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India. Lancet. 2004, 363: 1039-1040. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6.

Siegfried N, Muller M, Volmink J, Deeks J, Egger M, Low N, Weiss H, Walker S, Williamson P: Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, 3: CD003362-

Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ: Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2000, 14: 2361-2370. 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018.

Moses S, Plummer FA, Bradley JE, Ndinya-Achola JO, Nagelkerke NJ, Ronald AR: The association between lack of male circumcision and risk for HIV infection: a review of the epidemiological data. Sex Trans Dis. 1994, 21: 201-210. 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00004.

Bailey RC, Plummer FA, Moses S: Male circumcision and HIV prevention: current knowledge and future research directions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001, 1: 223-231. 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00117-7.

Carael M, Cleland J, Deheneffe JC, Ferry B, Ingham R: Sexual behaviour in developing countries: implications for HIV control. AIDS. 1995, 9: 1171-1175.

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A: Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Med. 29: e298-

Drain PK, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, Koutsky LA: Determinants of cervical cancer rates in developing countries. Int J Cancer. 2002, 100: 199-205. 10.1002/ijc.10453.

United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Report 2004. 2004, New York: Oxford University Press

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic 2004. 2004, Geneva: UNAIDS

Smith JS, Robinson J: Herpes simplex virus infections: a review of seroprevalence worldwide. J Infect Dis. 2002, 186 (Suppl 1): S3-28. 10.1086/343739.

Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM: GLOBOCAN 2000: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Prevalence Worldwide, Version 1.0. 2001, International Agency for Research on Cancer CancerBase No. 5 Lyon, IARCPress, [http://www-dep.iarc.fr]

George Schmid, World Health Organization: Personal communication on June 4. 2004

World Health Organization: Hepatitis C – Global Prevalence (update). Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 1999, 49: 425-427.

Bailey RC, Neema S, Othieno R: Sexual behaviors and other HIV risk factors in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999, 22: 294-301.

Kebaabetswe P, Lockman S, Mogwe S, Mandevu R, Thior I, Essex M, Shapiro RL: Male circumcision: an acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana. Sex Transm Infect. 2003, 79: 214-219. 10.1136/sti.79.3.214.

Addis Ababa University, Family Health International: Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BSS), Ethiopia 2002. 2003, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University, Family Health International

Kenya Bureau of Statistics/Ministry of Health/Medical Research Institute/Center for Disease Control Macro International: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2003. 2003, Calverton, Maryland: Macro International, [http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR151/13Chapter13.pdf]

World Health Organization/Global Program on AIDS: 1989 Uganda Survey. 1989, Geneva: World Health Organization

Macro International: Demographic and Health Surveys data base. 2004, Calverton, Maryland: Marco International, [http://www.measuredhs.com]

Measure Evaluation: Central Statistical Office/Ministry of Health, Zambia. Zambia Sexual Behavior Survey. 2003, [http://www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/pdf/tr-04-19.pdf]

United Nations Population Division: World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision. 2001, New York: United Nations

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: HIV/AIDS Epidemic Update 2002. 2002, Geneva: UNAIDS

United States Central Intelligence Agency: The World Factbook 2001. 2000, Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, [http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook]

StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0. 2004, College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation

Caldwell JC, Caldwell P, Orubuloye IO: The family and sexual networking in sub-Saharan Africa: historical regional differentials and present-day implications. Population Studies. 1992, 46: 385-410. 10.1080/0032472031000146416.

Carael M: Sexual behaviour. Sexual Behaviour and AIDS in the Developing World. Edited by: Cleland J and Ferry B. 1995, London: Taylor & Francis, 75-123.

Halperin DT, Epstein H: Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa's high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004, 363: 4-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3.

Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ: Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. STI Online. 2006, 82: 101-110.

Szabo R, Short RV: How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?. BMJ. 2000, 320: 1592-1594. 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592.

Patterson BK, Landay A, Siegel JN, Flener Z, Pessis D, Chaviano A, Bailey RC: Susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of human foreskin and cervical tissue grown in explant culture. Amer J Pathology. 2002, 16: 867-873.

Halperin DT, Steiner MJ, Cassell MM, Green EC, Hearst N, Kirby D, Gayle HD, Cates W: The time has come for common ground on preventing sexual transmission of HIV. Lancet. 2004, 364: 1913-1915. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17487-4.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/6/172/prepub

Acknowledgements

Supported by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research Grant AI 27757 and University of Washington STD Cooperative Research Center Grant AI 31448. The National Institutes of Health had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors wish to thank David Wilson, Antonio de Moya and Jeff Marck for reviewing classification of countries by male circumcision prevalence, King Holmes and Beth Weaver-Green for reviewing drafts of the manuscript, and Mary Fielder and Ron Nelson for assistance with manuscript preparations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PKD, DTH, JPH, and RCB designed the study. PKD, DTH, and RCB collected and analyzed data. PKD, DTH, JPH, JDK, and RCB interpreted the results. PKD primarily wrote the manuscript. DTH, JPH, JDK, and RCB provided valuable insight for revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Drain, P.K., Halperin, D.T., Hughes, J.P. et al. Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases: an ecologic analysis of 118 developing countries. BMC Infect Dis 6, 172 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-6-172

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-6-172